Gender and Sexual Politics of Pacific Island Militarisation:

A Call for Critical Militarisation Studies

Victor Bascara, Keith L. Camacho and Elizabeth DeLoughrey

-

Militarisation is something of a proverbial elephant in the room when considering the once and current course of empire. When Pacific militarisation has been examined, the focus often turns to the strategic military history of World War II or draws on an unreconstructed area studies, uncritically complicit with development and its methods of being realised. The Pacific Islands are therefore at both the centre and the margins of any reckoning with the colonial and neocolonial history of state violence in the region. The authors in this volume call for a critical militarisation studies (CMS); one that weaves the complex histories of state violence in the region in relation to issues of ethnicity, indigeneity, gender and sexuality. CMS also calls for scrutiny of the diversity of discourses expressed by communities complicit in regimes of militarisation as well as those articulating cultural and political modes of demilitarisation and resistance.[1] Critical militarisation studies entails a strategic centring of alternative communities and epistemologies that apprehend and engage with the legacies and currency of Pacific Island militarisation. The research featured here calls attention to how gender and sexuality serve as critical nodes for challenging the dominant and often masculine terms of corporate, military, and state governance, humanitarianism, and warfare in Asia and the Pacific.[2] The work collected in this special issue builds on important ongoing discussions of the constitutive role for gender and sexuality for understanding notions such as empire, war, security, development, resistance and subalternity, made legible and meaningful through a critical engagement with militarisation in the Pacific.[3]

-

This is a vital time to reckon with these complexities as new social movements for decolonisation have been refocusing attention on the complex material and ideological conditions that manifest in the gendering of diasporas, of military service by the currently/formerly colonised, of indigenous sovereignty mobilisations, of labour organising amidst flexible capitalism, and myriad forms of critical cultural production.[4] This collection emerges at a time of increasing and persistent militarism in the Pacific as well as an important moment of remapping the region in ways that are not exclusively tied to state formations, or language or cultural histories. The people and places of the Pacific, some have said, are always 'on the move,' and much of that mobility and exchange arises from the structures of militarisation.[5] The scholarship in this volume emerges from these new developments that extend, reshape and interweave such fields as gender and queer studies as well as military history and area studies, featuring interdisciplinary research on the legacies of Pacific Island militarisation, and critically emphasising the dialectical relationship between gendering and militarisation in Fiji, Guam and the Marianas, Okinawa, and the Philippines.

-

These articles derive from a collective of interdisciplinary scholars whose archival investigations, ethnographic field studies, and community collaborations bring together diverse audiences within and beyond the academy and across the Pacific. The essays are the result of two research workshops we conducted on the Legacies of Pacific Island Militarisation at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 2011, an effort graciously sponsored by a broad base of University of California constituencies.[6]

-

In addition to these workshops, we invited Professor Teresia Teaiwa of Victoria University of Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, to deliver a keynote address on Fijian women soldiers at University of California,

| |

Los Angeles (UCLA), a version of which is reproduced in this volume. We also coordinated a poetry reading and community dinner at the Pacific Islands Ethnic Art Museum in Long Beach, California, in order to facilitate a dialogue between our faculty colleagues and distinguished poets with the Pacific Islander artists, educators and families of the area. Our conversations about Fiji and Guam or about Okinawa and the Philippines had much to do with our relationships to each other and these sites as much as they had to do with a collective analysis of militarism. Our call for critical militarisation studies thereby supports local and regional collaborations on and interdisciplinary analytics about the study of militarism that would otherwise not materialise because of the colonial, disciplinary and geographical divisions across the Pacific. These sensibilities require a nuanced appreciation, then, of the complex histories of anti-nuclear, anti-war and feminist movements in the region in an effort to create and sustain related decolonial and social justice movements now and into the future.

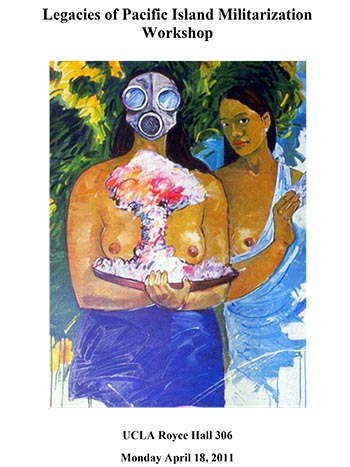

Figure 1. André Marere, 'After Gauguin,' 1986

Source. Courtesy of the artist, André Marere.

|

These public forums sought to address questions such as: How does militarism inform and shape social environments? How does the experience of state regimes of violence produce new cultural practices and modes of expression in literature, the arts, activism and politics? Our conversations highlighted multiple methodologies of approaching the complex gendered, social, political and cultural implications of Pacific Island militarisation, thereby demonstrating a cross-regional, multilingual and vibrant brand of Pacific Studies that is not tied to a single language or colonial origin (particularly Anglophone), nor caught in a binary between the 'Rim' and the 'Basin.' Turning to militarisation as a frame was vital for mapping alternative notions of the region that crossed and even contested various colonial, political and language histories as they have been articulated in Pacific Studies. By productively engaging the ongoing legacies of US, Japanese and Fijian military histories, critical militarisation studies thus offers an interdisciplinary, comparative and justice-oriented approach that cannot be limited by the singular and often masculinist histories of nation states and their empires.[7]

The scholarship here addresses multiple sites of the gender and sexual politics of militarisation in the Pacific including activism, film, oral histories, and music in Fiji, Guam, Japan, Okinawa and the Philippines. They examine the colonial legacies of US, Japanese and Fijian militarisation in relationship to both state and familial violence, engage national as well as transnational networks, and bring institutional state networks in relationship to the racialised and gendered production of heteronormative intimacy and the domestic. Topics range from gender and contemporary Okinawan indigenous movements, 'placental politics' of Chamorro midwifery in Guam, Third Cinema and the sexualised spectacle of US/Japanese militarisation in Okinawa, Filipino kinship and US military service, the politicisation of traditional Okinawan musical performance, and the complex historical conditions of Fijian women soldiers.

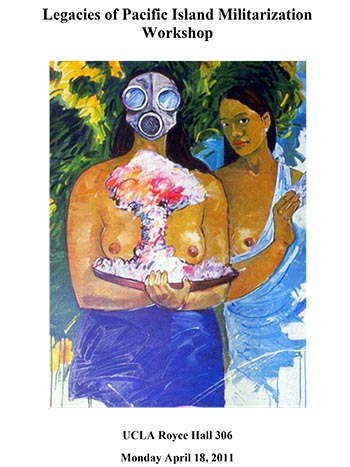

Figure 2. UCLA Royce Hall 306, 18 April 2011, Legacies of Pacific Islands Militarization workshop participants. Front row (l. to r.): Teresia Teaiwa, Ayano Ginoza, Christine Taitano DeLisle, Setsu Shigematsu, Theresa Suarez, and Wesley Ueunten. Back row (l. to r.): Elizabeth DeLoughrey, Keith Camacho, Dean Saranillio, and Victor Bascara

Source: Photographer, Victor Bascara, 18 April 2011

Christine Taitano DeLisle, in 'A History of Chamorro Nurse-Midwives and a "Placental Politics" for Indigenous Feminism,' examines Chamorro nurse-midwives (pattera) in work that draws from her larger book project on the historical relations between Chamorro women and white American Navy wives in Guam in the first half of the twentiethg century. DeLisle argues that through confronting and negotiating the gendered work of Navy wives and their efforts to transplant white womanhood into Guam, Native women forged new political, social and cultural spaces from which they aided and abetted colonialism, but also constructed new forms of Chamorro consciousness and new notions of indigenous progress. These modes and ideas, she further argues, comprised an emergent Chamorro modernity—novel ways of asserting and performing indigeneity in relation to the US and American practices such as speaking English, attending schools and hospitals, donning American-style dress and fashion, socialising in dance halls, and saluting flags—without necessarily abandoning deep indigenous values and practices.

In the twentieth century alone, the Chamorros of the Marianas and the Okinawans of Okinawa, as well as their respective settler populations, have separately and sometimes uniformly suffered issues of cultural, linguistic and political loss as a result of wars waged by and between Japan and the US.[8] Issues of colonial education, labour exploitation, land displacement, military enlistment, nuclearism and sexual violence likewise comprise these histories.[9] Given these colonial contexts, Chamorro and Okinawan bodies can be theorised as subject formations that are differentially produced outside the 'normatively human,' or the white, rights-bearing subject of modernity.[10] In fact, Chamorros and Okinawans historically figure in American and Japanese juridical and political thought as ambivalent, semi-citizen bodies, neither fully legally recognised nor widely grieved by Japan and the US.[11]

In 'Mobilizing Indigeneity in Okinawa as a Form of Resistance to U.S. Militarism,' Ayano Ginoza examines articulations of Okinawanness that are messily constructed around the understanding of Okinawans as Japan's ethnic minority and/or as a political category. By analysing contemporary literatures, autobiography, and United Nations' documents on racism and indigenous people's human rights, Ginoza examines the mode of Okinawanness as expressed in two forms: Okinawans as a Japanese ethnic and racialised minority, and Okinawans as uchinanchu or indigenous peoples. These two forms of articulations of Okinawanness appear in varying cultural and political contexts as political tools to confront, negotiate and work out the tensions that are produced in the touristic and militaristic processes of interdependent empires. In addition, she examines the implications, challenges and contributions of the contemporary expressions of Okinawanness to the emerging field of Native/Indigenous Studies across Asia and the Pacific.[12]

Setsu Shigematsu in 'Intimacies of Imperialism and Japanese-Black Feminist Transgression: Militarised Occupations in Okinawa and Beyond' asks, how we should recalibrate our scholarship about militarisation in and across the Pacific in ways that create more effective transnational and cross-regional alliances with ongoing decolonisation efforts? How should we develop modes of cross-racial solidarity and cross-racial critique that do not foreclose a collaborative decolonial political future? The focal point of this article is an analysis of the film Extreme Private Eros by the experimental Japanese director Hara Kazuo. By depicting the practices of diasporic Japanese feminists in the early 1970s who engage in cross-racial relations with Black American GIs in Okinawa during the Vietnam War, this text is replete with contestatory crossings, inviting lines of inquiry. Working against the common portrayal of Asian prostitutes for American GIs, this film stages Japanese feminists inserting themselves within militarised Okinawa. This documentary-style film projects the transpacific connections between Japanese diasporic feminism, black liberation and the Japanese left during the early 1970s, returning us to the political period that simultaneously catalysed the formation of US Ethnic Studies and women's and feminist studies. Shigematsu's critical engagement with this period analyses the unresolved contradictions of this radical phase, interrogating specifically the intersecting conditions of US- Japanese neo-imperialisms and the transpacific cross-fertilisations of liberation movements.

Theresa Suarez, in 'Filipino Daughtering Narratives: An Epistemology of US Militarization from Inside,' examines how daughters of Filipino U.S. military personnel in her study have enacted (or as local colloquialism might playfully describe as 'overacted') gendered notions of national belonging to a US imperialist 'state' precisely to challenge prescriptive heteropatriarchal family expectations at home. As Cynthia Enloe argues succinctly, 'successful demilitarization calls for changing the relationships between masculine authority figures and feminized "dependents."'[13] The spectre of US imperial authority takes the form of Father, Poppa/Papa, Pappy and Daddy (and other real and fictive kin) who wear—or have worn, however ill-fitting—a U.S. military uniform. The gaze of imperial authority is the 'well-entrenched battleground of one's familia,' as Vicente M. Diaz describes eloquently.[14] To extend his treatise even farther though, Enloe asks, what is it like for daughters of Filipino US servicemen to live in Diaz' metaphorical 'Pappy's House'? Whether 'Pappy's House' is constructed as contingent military housing, or the permanence of a long sought-after single-family suburban home, how is the imperial gaze of militarised authority reproduced as heteropatriarchy in the family home? How do these daughters negotiate heteronormative expectations of womanhood from 'Dad,' whose sense of racialised masculinity was sutured within militarised structures of US imperial authority? What forms of 'meaning remaking' are made possible by and for these women to deal with the intimate ways that US militarism and family loyalty become inextricably connected? Can they move out of 'Pappy's House' to explore their own notions of womanhood, and if so, how? If not, must they choose to join the US military themselves in order to leave?

Wesley Ueunten's 'Making Sense of Diasporic Okinawan Identity within US Global Militarisation' reflects on and analyses the conditions and critical perspectives of the Okinawan diaspora. Ueunten particularly explores the terms of visibility made possible by the emergence of 'the Okinawan Boom,' a rise of cultural productivity that witnessed the prominence of Okinawan music in particular. He critically considers this development not only from the standpoint of a scholar of Okinawan history, but also as an interested cultural practitioner himself. Emphasis is on the effect of this development on the meanings and emotions that Okinawans—especially those in the diaspora—attach to music from home. By examining the increased prominence of these cultural practices in the diaspora, he argues that Okinawan music is being brought in to line with American and Japanese interests to keep the US military bases in Okinawa. As Enloe observes, 'Militarization is such a pervasive process, and thus so hard to uproot, precisely because in its everyday forms it scarcely looks life threatening.'[15] Similarly, the US militarisation of Okinawan music is not blatantly violent or discriminatory; it is thus a part of the 'everyday' in Okinawa. And while the militarisation of Okinawan music is not an open act of cultural genocide, he argues that this process nevertheless normalises or masks the US military presence in Okinawa.

Teresia Teaiwa, in 'What Makes Fiji Women Soldiers? Context, Context, Context,' examines the legacies of Fijian military service in and out of colonialism. The Fiji military is of particular interest because it is the largest indigenous military in the Pacific region, its leaders are tied to three state coups (in 1987, 2000 and 2006), and it has an important peacekeeping battalion contracted by the United Nations for duties in East Timor, Lebanon and Iraq, not to mention thousands of soldiers working internationally in private security industries. Based on archival research and conclusions drawn from interviews with women in the Fiji Military Forces (FMF), Teaiwa's essay argues that in order to demilitarise, we must examine the co-constitution of the military and civilian society to have an understanding of their mutual production of values. Turning to Fiji she examines how the concept of woman has shifted to become effectively militarised, particularly in the wake of an indigenous nationalism that refashioned a colonial institution of militarism into one associated with social mobility.

While each article is a rigorously examined case study, important interventions resonate across the issue as a whole. Appreciated collectively, such resonant themes of kinship, economy, repression, violence and the state, as well as desire, sovereignty, agency and subalternity draw out the shared legacies, desires and critical practices these cases make evident. Whether examining music, military service, midwifery, movies or movements, the convergent critical commitments of the articles in this issue engage with and extend transformative knowledge production on the histories, experiences and discourses that have both legitimated and especially undermined the proliferation of Pacific Island militarisation.

Conclusion

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the rapid and ongoing militarisation of the Pacific, particularly in an era of the 'Pacific Pivot,' demands a dialogue about the multiple methodologies of approaching the complex social, political, environmental and cultural implications of militarism, past and present. Underscoring American strategic interests, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton defined the 'Pacific Pivot' as 'maintaining peace and security across the Asia-Pacific … whether through defending freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, countering the proliferation efforts of North Korea, or ensuring transparency in the military activities of the region's key players.'[16] Enacted under Barack Obama's administration, the Pacific Pivot entails increased American surveillance over the countries and peoples of these locales, demanding their cooperation and transparency on many fronts but not suggesting that the United States do the same. Through our call for a critical militarisation studies in the Pacific we thus appreciate ways in which community organisers, filmmakers, musicians, journalists, and scholars of the Pacific Century have responded to the legacies of militarisation as an ongoing crisis, of which the so-called Pacific Pivot is the newest manifestation.

A long history of militarism in the Pacific has set the conditions for a return to the speculations and resistances that have made the entire region of the Pacific Rim both hotly contested and curiously underexamined. Nearly a quarter century ago, Kanaka Maoli scholar-activist Haunani-Kay Trask observed, 'First World militarization of the region is more contested since the Pacific evolved from a strange place with a few watering ports and frontier outposts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries into a strategic area for super-power nuclear politics, ocean and land mining and First World dumping in the twentieth century.'[17] By showcasing an international and interdisciplinary team of scholars, this issue aims to generate a dialogue about the gendered ways in which sovereignty is construed, negotiated and applied in the wake of state violence and empire making and remaking. Drawing from our different disciplinary backgrounds in the humanities and social sciences, we offer this issue and its call for a critical militarisation studies to provide an interwoven platform for interdisciplinary dialogue and transcultural approaches to the gendering of (de)militarisation within, and throughout, the Pacific.

References

[1] Cynthia Enloe, 'The recruiter and the sceptic: a critical feminist approach to military studies,' in Critical Military Studies (2014): 3–10, p. 5.

[2] Vera Mackie, 'Reimagining governance and security in the Asia-Pacific region,' in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, issue 15 (May 2007), online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue15/mackie.htm (accessed 3 December 2014).

[3] For examples, see Intersections issues 'Media and the Creation of New Japanese Women and Narrating War, Imperialism and the Nation,' issue 11 (August 2005), online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue11_contents.html (accessed 3 December 2014); 'Gender, Governance and Security in the Asia-Pacific Region,' issue 15 (May 2007), online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue15_contents.htm (accessed 3 December 2014); and 'Arts and Media Responses to the Traumatic Effects of War on Japan,' issue 24 (June 2010), online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue24_contents.htm (accessed 3 December 2014).

[4] Knut M. Rio and Edvard Hviding, 'Pacific made: Social movements between cultural heritage and the state,' in Made in Oceania: Social Movements, Cultural Heritage and the State in the Pacific, ed. Edvard Hviding and Knut M. Rio, Wantage: Sean Kingston Publishing, 2011, pp. 5–30, p. 16.

[5] For the Pacific on the move, see Vicente M. Diaz and J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, 'Native Pacific cultural studies on the edge,' in The Contemporary Pacific vol. 13, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 315–42. For new approaches to mapping the region through critical militarisation studies see Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho (eds), Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. For rethinking global studies through a mapping of the US military empire, see Catherine Lutz (ed.), The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Posts, New York: New York University Press, 2009.

[6] The editors acknowledge the generous support of the UCLA Burkle Center Faculty Research Working Group Grant, Humanities Division, Social Sciences Division, Department of Asian American Studies, American Indian Studies Program, Department of English, the Postcolonial Literature and Theory Colloquium, The Center for Southeast Asian Studies, The Cultures in Transnational Perspective Mellon Postdoctoral Program in the Humanities, The César E. Chávez Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies, The Center for the Study of Women, and The Asian American Studies Center as well as additional funding from the University of California Center for New Racial Studies and the University of California Pacific Rim Grant program.

[7] Catherine Lutz, 'Introduction: Bases, empire, and global response,' in The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Bases, ed. Catherine Lutz, New York: New York University Press, 2009, pp. 1–44, p. 39.

[8] See T. Fujitani, Geoffrey M. White and Lisa Yoneyama (eds), Perilous Memories: The Asia Pacific War(s), Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001.

[9] See Laura Hein and Mark Selden (eds), Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003.

[10] Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, London and New York: Verso, 2006, p. xiv.

[11] Keith Camacho, Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory, and History in the Mariana Islands, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘ i Press, 2011.

[12] On the emerging field of Native/Indigenous Studies, see Vicente M. Diaz and J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, 'Native Pacific Cultural Studies on the edge,' in The Contemporary Pacific vol. 13, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 315–42; Mishuana R. Goeman and Jennifer Nez Denetdale, 'Native feminisms: Legacies, interventions, and indigenous sovereignties,' in Wicazo Sa Review,vol. 24, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 9–13; Hsinya Huang, 'Sinophone indigenous literature of Taiwan: History and tradition,' in Sinophone Studies: A Critical Reader, ed. Shu-mei Shih, Chien-hsin Tsai and Brian Bernards, New York: Columbia University Press, 2013, 242–54; John Balcom and Yingtsih Balcom (eds), Indigenous Writers of Taiwan: An Anthology of Stories, Essays, and Poems, translated with an introduction by John Balcom, Columbia University Press, 2005; and Jolan Hsieh, Collective Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Identity-Based Movement of Plain Indigenous in Taiwan, New York: Routledge, 2010.

[13] Cynthia Enloe, Globalization and Militarism: Feminists Make the Link, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2007, pp. 135–36.

[14] Vicente M. Diaz, '"Pappy's House": "Pop culture" and the revaluation of a Filipino American "sixty-cents" in Guam,' in East Main Street: Asian American Popular Culture, ed. Shilpa Divé, Leilani Nishimi and Tasha G. Oren, New York: New York University Press, 2005, 95–113, p. 97.

[15] Cynthia Enloe, Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, p. 3.

[16] Hillary Clinton, 'America's Pacific Century,' in Foreign Policy, November 2011, online: http://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century.html (accessed 3 December 2014).

[17] Haunani-Kay Trask, 'Politics in the Pacific Islands: Imperialism and native self-determination,' Amerasia Journal vol. 6, no. 1 (1990): 1–19, p. 4. See also Candace Fujikane, 'Asian American critique and Moana Nui 2011: Securing a future beyond empires, militarized capitalism and APEC,' in Inter-Asia Cultural Studies vol. 13, no. 2 (2012): 189–210.

|