Intimacies of Imperialism and Japanese-Black Feminist Transgression:

Militarised Occupations in Okinawa and Beyond

Setsu Shigematsu

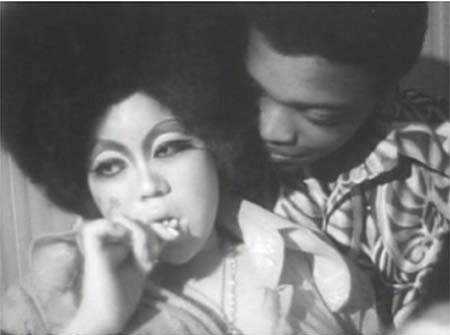

Figure 1. American GI and a Japanese feminist named Sugako who works as a bargirl in Okinawa, Japan in 1972

Source: Hara Kazuo's film, Extreme Private Eros, Love Song 1974

|

-

The above image is from Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974, Hara Kazuo's cinéma vérité style film that depicts Japanese feminists consorting with Black American GIs in Okinawa.[1] This film captures transpacific imperial intimacies of Japanese feminism, Black GIs and the US militarised occupation of Okinawa during the early 1970s. Through an analysis of Extreme Private Eros, I illuminate the intersections of US and Japanese neo-imperialism and colonialism, militarised occupations (of soldiers, Asian bargirls, and Okinawa), heterosexism and racism as the structuring conditions that produce the contradictory dynamics of feminist practices of sexual liberation.[2] I examine the entangled intimacies of US and Japanese neo-imperialisms that manifest through the sexualised relations between American soldiers and Asian women in contact zones such as Okinawa. My analysis reveals that the intimacies of imperialism are often intertwined with liberation movements that are conceived as anti-imperial; these movements must therefore undo their own conditions of existence. These are the vexed and contradictory conditions that I explore in this article.

-

My interpretation of this film is informed by my research on the Japanese women's liberation movement and a broader concern with the transpacific cross-fertilisation of liberation movements during the 1960s and 1970s.[3] My notion of imperial intimacies refers to the collusion between US and Japanese neo-imperialism(s), and the imperial-militarisation of intimate spaces, racialised-sexual encounters, modes of kinship, complicity and reproduction.[4] 'Imperial intimacies' also gestures toward the transpacific roots/routes of this radical Japanese feminist movement that are traceable to transpacific liberation (US feminism and Black Power) and anti-imperial movements (Anti-Vietnam War and New Left movements) that emerged in response to interlocking US and Japanese neo-imperialisms. For many activists of this radical feminist movement, the liberation of sex was key to human liberation. The movement supported women's sexual liberation from the confines of the patriarchal Japanese family system. This analysis complicates existing feminist approaches to militarised prostitution and Asian-Black relations by examining the relational dynamics of the Japanese feminists, Black Americans and Okinawans depicted in this film. Building on the work of scholars such as Cynthia Enloe, Katharine Moon and Ji-Yeon Yuh, this article further explores how anti-Black racism articulates through a discourse of women's relative empowerment. This discussion demonstrates how Japanese feminist liberation practices are thus contradictory forms of resistance and subject formation, and can come into conflict with other trajectories of liberation. My analysis demonstrates how even anti-imperialist feminist practices can unwittingly replicate racist and colonial modes of being and therefore underscores the imperative of an intersectional and decolonial feminist analytic.

Con/text of the 1970s: Filming movements and occupations

-

Extreme Private Eros (hereafter EPE) depicts the militarised occupation of Okinawa in the early 1970s as the context for an intimate exposé of the private lives of the controversial Japanese filmmaker Hara Kazuo and his then-wife, Takeda Miyuki.[5] EPE traces the unconventional relationship(s) between Takeda, Hara and his new lover and partner, Kobayashi Sachiko.[6] At the beginning of the film, Hara states that he made the film as a means to continue his relationship with Takeda.[7] She was an activist in the Japanese women's liberation movement who ardently expressed her independence through transgressive actions (such as her openness about her erotic and sexual relations with others outside the marriage). Since its release in the mid-1970s, EPE continues to be shown in Japan and internationally, providing a provocative visual ethnography of the impact of US militarisation in places like Okinawa and beyond. Its continued circulation and global availability in DVD format enables an ever-widening audience to view this striking experimental film.

-

Hara began filming EPE in 1972. This was a significant year because it marked the official reversion of Okinawa from US military governance (which had been in effect since 1945) to the Japanese government. Despite the reversion, nearly 75 percent of all US military bases in Japan have been concentrated in Okinawa, which comprises less than 1 percent of Japan'?s land mass. These figures demonstrate how Japanese governance maintains this disproportionate US military occupation, constituting what Ayano Ginoza refers to as the ?interdependent colonialisms? of Japan and the US.[8] The imposition of US bases and thousands of troops has disproportionately subjected Okinawa and its people to continuous dangers, pollution and assaults, structuring a neo-imperial-colonial condition that is justified through the rhetoric and formalities of US and Japanese democracy.[9]

-

One of the results of such military occupations is the establishment and regulation of a militarised sex-entertainment industry. As Enloe, Moon and others have underscored, militarisation is a thoroughly gendered process with deep implications for people within and beyond the military.[10] Through this film, the audience is taken into the intimate settings of militarised encounters and exposed to the complex sexual economies of Asian-Black-White relations. In contrast to documentary films about US military prostitution, such as The Women Outside (1996), Camp Arirang (1995) and Sin City Diary (1992), EPE depicts an unusual feminist response by portraying Japanese women inserting themselves into this cross-racial sexual economy as an articulation of their freedom, relative mobility and transgressive desire.[11]

-

The majority of the film depicts Takeda's experiences as she sojourns in Okinawa for ten months. Film historian Jeffrey Ruoff describes EPE as a cinéma vérité style film that is ?accentuated by jump cuts, the lack of establishing shots, flash frames, first-person voice-over, and a handheld camera.?[12] This ninety-eight minute black and white film is comprised of twenty-five film sequences that construct a narrative of Hara and Takeda's relationship, and of their son Rei. The camera appears to capture the unscripted realism and naked truths of Takeda's multiple relationships in Okinawa: a volatile romance with her women's lib girlfriend Sugako, an affair with a Black GI named Paul, and the triangulated relationship with Hara and Kobayashi. Interspersed are scenes of the bar where they work, followed by a sequence about an Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi. The viewers see Takeda's short-term attempt to run a daycare for the children of Okinawan bargirls. She unsuccessfully attempts to adopt a Black-Okinawan baby. After ten months, Takeda states that she is ?sick of Okinawa? and returns to Tokyo, where she gives birth in front of Hara's camera. The film ends in 1974 with a sequence of scenes of Takeda living with her children in a women's lib commune and working as a topless gogo dancer.

-

EPE captures the exuberance and pain of the counter-culture movement era. Hara often speaks about how deeply imprinted he was by the social movements of the late 1960s and 1970s. In an interview published almost two decades after the release of EPE, Hara states:

In the sixties and seventies, there was a feeling that if the individual did not cause change, nothing would change. At the time, I wanted to make a movie, and I was wondering how I could make a statement for change. At the time, there was much talk of familial imperialism [kazoku teikokushugi]. One of the strong sentiments of the time was that familial imperialism should be destroyed. I thought that if I could put my own family under the camera, all our emotions, our privacy, I wondered if I might break taboos about the family.[13]

-

Hara's statement highlights how the relationship between individual action and societal transformation can be documented and amplified through the filmic medium. While placing his own family under the camera, he and Takeda together break the norms of the Japanese family system. Through his camera, Hara exposes their private lives, creating his own vision of the personal as political, splicing together filmic fragments of their struggles, fights and sexual encounters. The violation of privacy and the breaking of social taboos are the hallmarks of Hara's confrontational films.[14] Hara describes how the movements of the sixties and seventies heralded liberation and attacking social taboos, and that it was this sense of confrontation and freedom bound together with this kind of destruction or deconstruction that he also sought to express in his films.

Feminist optics/co-opting feminism

-

Hara did not intend his film to represent the women's liberation movement.[15] My analysis, however, is shaped by a decade of research and sustained interviews and dialogues with many of its activists. Leading movement activists, such as Tanaka Mitsu, were angered by his film and critiqued it as symptomatic of a ?male gaze.?[16] Due to the film's circulation, Takeda's actions became more visible compared to most other activists in the movement.[17] Thus regardless of the film's representativeness of the women's lib movement and the accuracy of its portrayal of bargirls and Black GIs, EPE?s cinematic form and international circulation render it representative. Compared to other films about the movement that offer coherent and seamless narratives of feminist progress, EPE reveals a cinema of truth about the contradictions of sexual liberation.[18]

-

The Japanese feminist movement known as ūman ribu emerged in 1970.[19] It was an urban-based movement comprised of mainly middle-class to lower-middle-class Japanese women in their twenties and thirties. This movement heralded women's sexual liberation from the confines of the male-centred Japanese family system. The activists criticised the family system as a microcosm of Japanese imperialism and the fundamental social unit that reproduced discrimination.[20] Their rejection of the Japanese family system was thus informed by anti-imperialism, and was foundational to their notion of the liberation of sex.

-

The anti-imperialist internationalism of the Japanese New Left and student movements were the immediate predecessors that catalysed the formation of the women's liberation movement in Japan. Leftist activists criticised Japanese support for US imperialism in Asia and organised mass rallies against the American military occupation of Okinawa and regular protests against Japan's support of the US War in Vietnam during the late 1960s and 1970s.[21]

-

As part of a broader anti-imperialist critique, ūman ribu activists criticised the gendered consequences of the US military occupation of Okinawa. Their political writings denounced how Okinawan prostitutes were being ?raped by US soldiers? and offered as the sacrificial frontline of Japanese-US imperialism. This feminist criticism of the gendered dynamics of the imperial structure imposed on Okinawa is articulated in a 1970 ribu pamphlet.

Okinawa is our problem. As for our relationship with Okinawan women, due to the history and the way that the state has divided us, we cannot say that we are the same women as the Okinawan women.… Because we are women of the mainland, we are the women who belong to the class of oppressors… We cannot be liberated until Okinawa is liberated.… Okinawa functions as the mainland?s protective wall. The prostitutes that are being raped by American soldiers serve as Okinawa's protective wall. And in the sex that is sold by the Okinawan prostitutes, we can see the naked colors of Japanese imperialism that we must destroy.[22]

-

Activists of the ūman ribu movement articulated this critique of the violent sexual effects of the US military occupation in Okinawa as a manifestation of Japanese imperialism. This pamphlet also clearly articulates the stark distinction between the Japanese and Okinawans, labelling the former as the oppressors based on the history of Japan's colonisation of the territory since 1879. It also points to the gendered/classed positionality of Okinawan bargirls/sex workers vis-à-vis other Okinawans. Although this pamphlet clearly states that Japanese women's liberation was linked to Okinawa's liberation, ūman ribu activist criticism did not immediately translate into an effective anti-imperialist (or anti-colonialist) feminist practice with Okinawan women and bargirls. Such Japanese anti-imperialist feminist discourse may indeed have motivated Takeda's exploration of Okinawa. The desire to see and experience how the oppressed other lived was characteristic of a broader Japanese leftist social movement practice of the era that encouraged learning about the conditions of the oppressed through direct experience. For example, while in Tokyo, Takeda worked with disabled citizens? groups; she sought to create solidarity with criminalised mothers (who were incarcerated for killing their children) by trying to know them as directly as possible, by visiting and writing them letters. Takeda embodied one example of how a radical feminist defied the proper norms for middle-class Japanese women, expressing the liberation of women's body and sexuality. She worked as a nude model and as a topless dancer, and these expressions of her liberation—which involve a process of confrontation and critical engagement with heterosexist systems—are captured and shared through Hara's camera. She was active in the creation of communes where women could raise their children with other women outside the confines of a male-centred family system. Takeda's maverick feminist lifestyle at times exceeded what other activists in the movement were willing to endorse; however, her deliberate defiance of sexual mores for middle-class women was representative of how many feminists refused the gender norms of Japanese society.[23] Her mobility, agency and freedom to travel to Okinawa was premised on her relative privilege as a middle-class Japanese woman and feminist political desire.

-

While there are a multitude of themes to be explored in this evocative film, this article focuses on the contradictions of Japanese feminist liberation as illustrative of the intimacies of imperialism and feminism. I argue that Takeda's actions represent the contradictions of a first world (imperialist) anti-imperialism and demonstrate the need for a decolonial feminist praxis. The latter requires a more intersectional engagement with the structures of colonialism and racism and offers a means to critique how certain first world feminist approaches to women's liberation can reproduce colonial relations and representations. This decolonial feminist analytic informs my reading of this film and its context.

-

A close analysis of Takeda's actions reveals some of the tensions, contradictions and limits of certain first world feminist notions of liberation that are also common problems among other liberation movements. For example, Takeda can be seen as more invested in pursuing her own liberation than working for the collective good, indicative of the tensions between liberal individualism/individualist empowerment versus collective liberation.

-

My interpretation of Takeda, however, is in no way a personal indictment of an individual feminist per se, but rather a critique of a widely understood notion of liberation and how it is commonly practiced within a larger context of liberal humanist modernity. EPE thus serves as an allegory of the vexed conditions of first world liberation struggles that must undo their own privilege, power and desiring logics.

Rethinking Afro-Asian encounters through Okinawan-Black-Japanese transgression

-

The first film sequence begins with Hara stating that Takeda left Tokyo in 1972 and went to Okinawa with another young woman from the movement named Sugako.[24] After arriving in Okinawa, these young feminists, who were in their early twenties, began working at a club for Black American soldiers. Their decision was likely informed by their limited understanding of the Black struggle against White oppression in America. Takeda and Sugako were representative of a small number of ūman ribu activists who chose to work in the sex-entertainment industry (mizushōbai) during the early years of the movement. This practice was motivated by a feminist critique of the patriarchal and classist double-standard that divided women into either good/chaste wives versus bad/promiscuous women, a binary these feminists sought to deconstruct through their deliberate participation in this industry. This work also served the pragmatic need to earn money to support their activism and communal life. They were thus motivated by an anti-Japanese patriarchal feminist politics and they also sought to transgress class divisions that discriminated against women in the sex-entertainment industry.[25] The film portrays Takeda's friendships with other bargirls, expressing her desire for friendship across class lines. Her previous work reaching out to criminalised women in Tokyo also aligned with this anti-classist/anti-elitist politics.

-

What remained underdeveloped in the women's liberation movement—and evident through Takeda's actions—was a better understanding and critique of racism and colonialism globally and domestically.[26] Despite being able to critique how the militarised sexual violence against Okinawan's women's bodies was a result of Japanese imperialism, at the outset of the movement, Japanese feminists had not yet conceived an effective anti-imperialist or decolonial feminist practice. Indeed, this analysis further reveals the cleavages between an anti-imperialist feminist critique of gendered violence and an effective decolonial feminist practice. I make an analytical distinction between anti-imperialist and decolonial feminist practice. The latter requires an intersectional understanding of class, gender, ethnicity, race and nation which was lacking in the movement during the early years of its formation.[27] And as my analysis will later demonstrate, anti-imperialist feminism can involve colonising tactics.

-

EPE depicts a contradictory set of representations of Black soldiers, Black Power, and Black agency amid the intimacies of Japanese-US neo-imperialism. The third sequence in EPE depicts the racially segregated A-sign bar for Black American GIs where Takeda and Sugako work.[28] These scenes document the transplantation and translocal mediation of American structures of racism and racial segregation, whereby African Americans are drafted to fight and die for the United States, but are not equal enough to be entertained in the same clubs as White soldiers. Throughout the film, Black GIs are always depicted in civilian clothing, which de-emphasises their militarised presence and power. They are seen dancing and lounging in the bar and hanging out with other Black soldiers. Through this set of images, overt codes of militarisation are elided, but function as the necessary suturing logic of such Asian-Black encounters. Black America encounters Asia at the extremities of the US militarised empire mediated through the transplantation of structures of racial hierarchy.

-

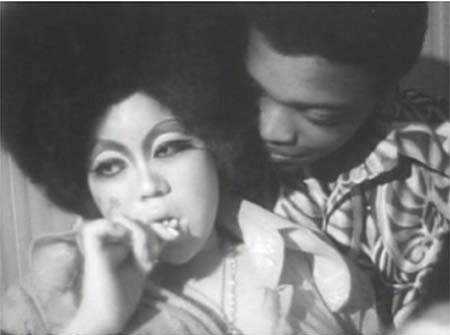

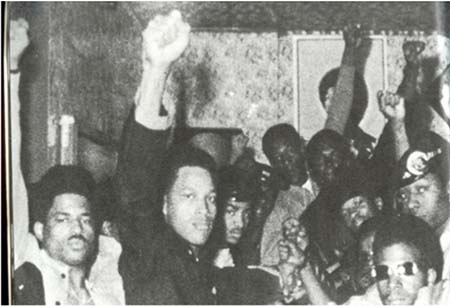

What is striking in EPE are the multivalent ways that Hara depicts Black GIs. In the image below, Black GIs pose with raised fists, linking them with other images of Black Power and resistance. These images and glimpses of Black Power consciousness in Asia attest to the transpacific movement of liberation consciousness and practice.[29]

Figure 2. Black GIs in Okinawa demonstrating their consciousness of Black Power

Figure 2. Black GIs in Okinawa demonstrating their consciousness of Black Power

Source. Hara Kazuo's film, Extreme Private Eros, Love Song 1974

|

-

What are the multiple meanings of this scene of Black Power consciousness in Okinawa, a zone of US military occupation? EPE provides rarely seen images of Black soldiers in Okinawa: as clientele in the bar and as part of this group expressing the Black Power salute; as Takeda's short term lover and as the lover of another bargirl named Chi Chi. EPE thus provides a portal to appreciate the complex status and figuration of the Black American GI at this historical juncture as occupier and lover, subject of desire and symbol of resistance.

-

Within such contact zones, these soldier-occupiers are present because they have been drafted into larger structures of US militarised imperialism. They may have sought respite from the racism they faced in the US through companionship with Asian women. What further complicates the visual representation of Black GIs in EPE is a voice-over during a montage sequence of scenes of this A-sign bar. The voice-over is a dialogue—spoken in broken English—between a bargirl named Kaylie (a friend of Takeda) and an anonymous Black GI client. The dialogue raises questions about the dynamics of Black-Asian-White power relations and provides viewers with the opportunity to hear the marginalised perspective of a bargirl working in Okinawa.

Bargirl: White people fool Black people right? Ok?

Soldier: White people?

Bargirl: White people use Black male right? Ok, long long time ago, right? Remember?

Soldier: That's why we still hold it against them now.

The bargirl then states that Black GIs have come to the "Orient" (sic) and treat Japanese women in the same manner, as if they are doing the same thing that Whites have done to Blacks. Although it may be a crude comparison, Kaylie expresses her critique of this racialised-gendered power relation. The Black GI protests her racial analogy.

You know that's not true. All people not do same thing. All GI no come Okinawa, Japan, and treat Oriental woman the same way. Some come and treat Oriental woman good, you know…

-

Even though the bargirl accuses the Black American GI of acting like the White man vis-à-vis the Oriental woman, the racialised status of the Black GI is not equivalent (or even accurately analogous) with that of a White man in these zones of military occupation. The conditions of White domination over Black people through the history of chattel slavery is neither equivalent to nor commensurate with the imperial militarism that has brought Black GIs to Asia. However, the bargirl's critique of the status of the Black GI does attest to an exploitative and contested gendered-racial hierarchy mediated by the sexual labour of the Asian bargirls. Although Black GIs can purchase sexual services, these bargirls are not the enslaved property of the soldiers.[30] Rather, as draftees, GI bodies are disposable property of the US government. Moreover, it is the heterosexist collusion of Okinawan and Japanese club owners and managers with the US military who support the maintenance of these gendered and racialised relations of power. Masakazu Tanaka has described this complex status of the American GI as occupier. In ?The Sexual Contact Zone in Occupied Japan,? Tanaka writes:

Although the US military is on the power end of occupation/colonisation, the American soldiers that the … girls solicited cannot be mass-labeled as the ?conquerors? because of the hierarchy that exists within the military system. The soldiers are mostly single men who are at the lower end of the military organisation. The American soldiers, although on the buying end of prostitution, are more intermediary in their existence than being direct representatives of those in power. They are potential critics of the military and of racial discrimination (if they are African-American), as well as potential deserters during the Vietnam War, they (re)emerge within Japan as military deserters, civil rights activists, and soldiers declaring solidarity with local civilians. In other words, they are rebels.[31]

This quote distinguishes between the status of low-ranking soldiers and African American soldiers compared to those who are in power (as policy-makers). Black American soldiers are situated as occupiers within a larger racial hierarchy and have agency to oppress and resist against structures of domination.

-

EPE projects the image of the Black male as rebel by including scenes of the Black Power salute. This recognition of the Black Power movement was part of the late 1960s and early 1970s Japanese New Left and student movement culture. Black liberation movements in the US also informed the Japanese New Left. In 1969, for example, two Black Panther members (Roberta Alexander and Elbert ?Big Man? Howard) were invited by student movement activists on a speaking tour in Japan.[32] In the wake of their visit, their works were translated by well-known leftists such as Muto Ichiyo and others, who formed the Committee to Support the Black Panthers. These are a few examples of transpacific cross-racial solidarity work.[33]

-

Black liberation thought also served as an inspiration for activists in the women's liberation movement. The leading philosopher-activist of the Japanese ūman ribu movement, Tanaka Mitsu writes about how US-based Black liberation thought helped crystallise her own radical feminist philosophy. In 1972, Tanaka wrote:

By calling White cops ?pigs,? the Blacks struggling in America began to constitute their own identity by confirming their distance from White centered society in their daily lives. This being the beginning of the process to constitute their subjectivity, who then should women be calling the pigs?[34]

-

Anti-racist militancy modelled and informed anti-sexist militancy for radical feminists in the US and Japan.[35] In her other writings, Tanaka also cites Angela Davis, indicative of a transpacific cross-fertilisation of liberation movements.[36] Black liberation struggle thus served as a transnational model of liberation. However, like other non-Black feminists and other leftist intellectuals, Tanaka learned lessons and cues from Black liberation, but she did not engage in anti-racist solidarity work and lacked an intersectional analysis of race, class and gender.[37] Ūman ribu discourse described Japanese women as a discriminated group, analogous to Japan's racialised minorities such as Okinawans, indigenous Ainu, and also former colonial subjects such as resident Koreans and Chinese. However, the claim to the same status of oppression conflates forms of domination without sufficient attention to different histories and structures of colonialism. Indeed, the lack of a racial/ethnic analysis of power differences informs how the activists of ūman ribu did not prioritise solidarity with other ethnic groups in Japan, but initially focused more on their own liberation, because they considered themselves analogous to these other oppressed minorities.

-

The focus on one's own liberation (or the liberation of one's own identity group) is a significant and vital aspect of any liberation struggle. However, an exclusive focus on one's own liberation can reinforce individualist/self-centred modes of empowerment and conflict with other liberation movements.[38] The lack of an anti-racist and anti-colonial analysis or practice is symptomatic of a single-axis feminist criticism that focuses on gender oppression, obscuring and/or excluding other indices of power. The racialised/ethnic position and class-privilege of Japanese feminist subjects such as Takeda might be constructively compared with the relative racial privilege of middle-class White feminists and the relative mobility of middle-class Asian American feminist women.[39] Historically, many first-world White and Asian/American women have struggled for their own empowerment according to a liberal feminist paradigm that has emphasised individual upward mobility. The larger context of anti-colonial and civil rights movements inspired the women's liberation movements during this era. However, the cross-fertilisation of movements was not always mutual.[40] The dominant discursive trajectory of Afro-Asian scholarship has been largely celebratory; however, this laudatory approach often leaves economies of Asian anti-Black racism unexamined.[41] It is this under-explored gendered-racial dynamic to which I now turn.

Asian bargirls mediating blackness—Chi Chi's remix

-

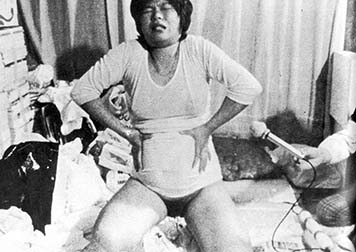

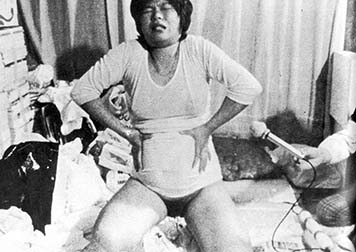

The fourth film sequence is about an Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi. Donning an afro-wig and heavy make-up, Chi Chi's very appearance transfigures self-expression through a racialised fashion-aesthetic that signifies an intimacy with blackness.[42] The audience is informed by Hara's voice-over that Chi Chi is a fourteen year-old Okinawan girl. The scene continues with Chi Chi telling Takeda that she is pregnant and does not know who fathered the child. This young teenager says her mother would kill her if she had the child, revealing her troubled situation at home. The sequence ends with the camera positioning the viewer in Chi Chi's room, as she gets undressed and begins having sex with an anonymous Black GI. Hara's camera lens implicates the viewer in this transgressive moment. Voyeuristic desire and curiosity are at once hailed and potentially disturbed. By confronting the viewer with this cross-racial scene between an anonymous young Black American soldier and a fourteen year-old girl the viewer is exposed to a spectacle of the transgressive intimacies of imperialism which is all the more provocative and unsettling given Chi Chi's age.

Figure 3. A fourteen year-old Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi and an anonymous Black GI

Figure 3. A fourteen year-old Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi and an anonymous Black GI

Source. Hara Kazuo's film, Extreme Private Eros, Love Song 1974

|

-

Hara's voice-over refrains from any overt criticism of how the US military sex industry impacts on Okinawan girls and women, but through the exposure of a fourteen year-old girl, EPE potentially conjures a narrative of lost innocence. By revealing Chi Chi having sex with an anonymous Black soldier, the film arguably stages the Okinawan girl as corrupted, and the Black soldier as an ambivalent subject of desire and an agent of defilement. His body is without a name, without a distinct story. He is client, lover and polluter, and a potential part of a collective struggle for liberation.

-

This implicit critique of the corrupting influence of the US military occupation takes place through the spectacle of this Black-Okinawan sexual encounter. This groundbreaking and visually transgressive film enables viewers to see and consume this Black-Okinawan sexual liaison while the White imperial subject remains outside the frame. The near complete absence of White American GIs from the film erases White agency from the constructed and transplanted racial hierarchy.[43] White heterosexist military governance structures these Afro-Asian relations as the authoritative power that imposes the segregation of entertainment venues by utilising Asian women as mediators of racial power. Although there is no explicit indictment of the racism of US imperialism in EPE, the Japanese-Black-Okinawan relationships are constituted within a larger structure of anti-Black racism that meshes with Japanese economies of light/white skin privilege.

-

In ?In the Black Pacific,? Bernard Scott Lucious writes, 'Colorism, therefore, is not simply a Black-White color-line problem of the African diaspora: it is also a Black-yellow color-line problem of Asian diaspora.'[44] Asian anti-Black racism in militarised-sexual contact zones has been described in Ji-Yeon Yuh's, Beyond the Shadow of Camptown (2004) and Katharine Moon's Sex Among Allies (1997).[45] In these important works, these scholars describe and detail the expressions, practices, and the effects of anti-Black racism, which is a much needed arena of historical documentation and analysis. However, such work often remains at the level of descriptive-reinscription by detailing the actions of women without critical commentary about the racism implied in their discourse.[46]

-

In Sex Among Allies, Moon documents the violent effects of racialised hierarchies within the militarised entertainment districts of Korea, known as camptowns.[47] Moon notes that if the women were found to be consorting with both Blacks and Whites, the women might ?risk economic and physical retaliation by White soldiers,? or if they discriminated ?against Blacks? and refused them, they would ?thereby risk the wrath of club-owners.?[48] Moreover, Moon writes that, ?For most prostitutes, racial discrimination served as a means to retain their limited freedom of choice of customers and their already compromised sense of self-dignity.?[49] In other words, to practice anti-Black racism is the root/route to preserve a relative degree of autonomy or dignity for prostitutes, who are already considered the ?lowest of the low.?[50] According to this logic, (White mediated) Asian anti-Black racist practice produces an economy of self-value that has material implications for the earning power and safety of bargirls and sex workers.

-

Euro-American anti-Black racism is thus transplanted and rearticulated in these militarised contact zones in Asia. These racial economies are re-inscribed, indexing Asian women's bodies through their intimacy with Black GIs. Such militarised occupations involve an interpenetrating racialisation between the soldier and the sex worker, each defining the other through the sexualised encounter. Asian sex workers are evaluated via their relative intimacy with Blackness and Whiteness as defining signifiers within a global racial hierarchy of life. In such contact zones, the American military occupation is maintained by the continued legacy of Japanese colonial governance producing the convergence of anti-Black and anti-Okinawan racism, both of which are animated by the logics of colonial racism.

-

Such dynamics warrant a further examination of the complex roots and modalities of Asian anti-Black racism, which differentially involves the multi-racial category of Asians (East Asian, Southeast Asians, South Asians). A further feminist decolonial analysis of Takeda's contradictory relationship with blackness helps illuminate these racial optics. By further examining Takeda's contradictions, this paper demonstrates how certain feminist discourses of women's liberation and empowerment (re)produce an economy of Asian anti-Black racism in the context of their intimacies with Black GIs.

Asian/Japanese anti-Black racial identity and phobia

-

For many feminist activists of the ūman ribu movement, sexual liberation implied having sex and giving birth outside the confines of the Japanese family system. Takeda passionately engaged these forms of anti-Japanese patriarchal practice; however, her pursuit of cross-ethnic and cross-racial relations were contradictory, conflicted and entangled within the racist structures of Japanese imperialist nationalism. In the fifth sequence in the film, Hara's voice-over reads the contents of a letter from Takeda. The letter informs him that Takeda is pregnant and she writes that she thinks that the ?father is Okinawan.? After ten months in Okinawa, Takeda travels back to Tokyo. She carries out her intention, stated earlier in the film, to give birth by herself in front of Hara?s camera.[51] Her intention to give birth without assistance on camera expresses her desire to publicly perform her independence and autonomy, indicative of a particular trajectory of (liberal) feminism that heralds individual female empowerment.

Figure 4. Takeda gives birth on camera in Hara's Tokyo apartment

Figure 4. Takeda gives birth on camera in Hara's Tokyo apartment

|

|

Figure 5. Kobayashi Sachiko records sound and Takeda's son Rei witness his mother giving birth.

Figure 5. Kobayashi Sachiko records sound and Takeda's son Rei witness his mother giving birth.

|

|

Source. Hara Kazuo's film, Extreme Private Eros, Love Song 1974

|

-

The narrative creates the expectation for Takeda (and the viewer) to anticipate a mixed Okinawan-Japanese child. After a highly graphic birthing scene where Takeda pushes out her baby onto the newspaper-covered floor of Hara's apartment, the child lies crying as Takeda briefly rests and recovers. To her surprise, Takeda discovers that her baby daughter is Black-Japanese. The birthing of her Black-Japanese daughter on camera captures the unanticipated outcome and progeny of her sexual liberation that transgresses Japanese familial-imperialism. The racial significance of this birth is prefigured and contextualised by Takeda's ambivalence about birthing a Black child expressed earlier in the film.[52] During one of Hara's visits to Okinawa, he and Takeda argue about her relationship with her Black GI lover, Paul. During this argument (in sequence 7), Takeda states that her relationship with Paul would only last while she was in Okinawa and that she was holding back because he is Black. One of Takeda's reasons for holding back is rooted in a fear about the colour of her progeny. During her argument with Hara, Takeda shouts, ?What do you think is going to come out? A White kid?!?[53] This exclamation reveals her anxiety about the colour of her offspring. This holding back due to Paul's blackness reveals how her transgressive sexual practice crosses the racialised boundaries of Japanese familial nationalism. Takeda desires to experience sexual relations with Paul, but she is reluctant to embrace the prospect of giving birth to a Black child.

-

After giving birth, Takeda phones her mother to tell her about the birth and that her baby is mixed-race. After discussing the child's skin colour, Takeda says, ?I can't kill her now, so I will raise her.? Her response to her mother reveals the stakes involved in the economies of cross-racial (anti-Japanese) sexual practice. This conversation with her mother also reveals Japanese discrimination against mixed-blood (konketsu) children, and how anti-Black racism can manifest despite the relative absence of Black bodies in Japanese society. Takeda's phobia of having a Black child is thus arguably informed by her recognition of the anti-Black racism that she also tries to challenge through her choice to raise her daughter.

-

While Takeda was in Okinawa, as noted above, she tried to adopt a Black-Okinawan baby boy named Kenny. Although she wanted to adopt a Black baby, she disclosed her resistance to bearing a Black child.[54] This distinction or contradiction is arguably rooted in a desire for racial self-recognition in her own offspring. The Black-Japanese sexual encounter thus involves a potential loss of racial self-recognition insofar as Japanese racial identity is predicated on a non-Black epidermal-spectrum that coheres East Asian racialisation.[55] According to this racial schema, East Asian racial legibility and coherence relies on a possessive investment in non-Black epidermalisation and light/white skin privilege.[56] The racial coherence of the (East) Asian subject is thus transfigured and reconstituted through its intimacy with blackness. These Black-American-Japanese encounters provide an opportunity to interrogate how the racialised identities of East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, Koreans) are transfigured in relation to blackness.

-

Even though transgressive cross-racial reproduction can be understood as an anti-Japanese patriarchal feminist practice, what was lacking in the women's liberation movement was a critical discourse of how Japanese (women?s) identity was predicated on a racialised imperial-colonial hierarchy of life. Even though their feminist discourse often acknowledged their positionality as imperialist oppressors (as noted above), their attempts to defy Japanese patriarchy often lacked practices of solidarity with other oppressed/colonised groups, despite their (mis)understanding of themselves as analogous with them. The opportunity for solidarity with Okinawan women or Black soldiers was underdeveloped and delimited by an emphasis on one's own liberation. This distinction between striving for one's own liberation and struggling with others for collective liberation is a relational dynamic that remains as a tension in the strategic pursuit of liberation.

Imperial feminist critique/critiquing imperial feminisms

-

EPE thus documents and exposes the various contradictions that arise in Takeda's attempts to forge a transgressive feminist politics. This narrative focus on Takeda's will to liberate herself centres her desire as the driving force that takes the viewer to Okinawa as the colonised stage for her liberation process. Takeda's desire to have sexual relations with Okinawan men and Black GIs trumps the imperative to struggle for political solidarity with them. The focus on sexual liberation in this radical feminist movement was its hallmark and its frontier.

-

After the scenes of Takeda's argument with Hara about her relationship with Paul, the sequence ends with the following inter-title: ?Her relationship with Paul lasted for three weeks.? There is no further information provided to explain their break up. No reasons are offered as to why Takeda proceeds to take an extremely hostile stance toward all Black GIs. In one of the final sequences of her stay in Okinawa, Takeda writes a pamphlet to give to Okinawan bargirls in Koza, an entertainment district for the US military. The pamphlet ends by encouraging Okinawan bargirls to do harm to Black GIs. Takeda specifically warns Okinawan women, 'Don't fall for Black guys with big cock…. Don't ever have sympathy for them. They should all be castrated.'[57] Through such an expression, Takeda disavows her own desire, and instead calls for gendered-racial violence against Black soldiers. Clearly, Takeda's conception of women's liberation (for Okinawan bargirls) is placed in direct conflict with Black American GIs. Takeda's pamphlet epitomises a first-world imperialist feminist desire to ?save? brown (Okinawan) women from Black men. Her discourse demonstrates a first world (imperialist) feminist desire to rescue the colonised by giving directives to Okinawan women, telling them what they need to do to liberate themselves from Black GIs. Indeed, the freedom and liberation of Black soldiers does not seem to factor into Takeda's political consciousness. Such anti-male discourse has characterised first-world radical feminist discourse by focusing solely on sexism without commensurate attention to the racial and classed power structures within larger structures of imperialism and colonialism. Through this inquiry, we can see how first-world Japanese feminists engage in sexual pursuits that can become colonising even though they began with anti-imperialist intentions to break down Japanese familial imperialism. Without adequate attention to racial hierarchies within colonial histories, even anti-imperialist feminism that seeks to defy Japanese familial imperialism can remain limited to a single-axis modality of sexual liberation and can fuel anti-Black male racism in the name of women's liberation. As a final point, Takeda's pamphlet provides an apt example of the distinction between first world anti-imperialism (what we may call imperialist anti-imperialism) and decolonial praxis. Even though ūman ribu activists were informed by an anti-imperialist critique (as seen in the ribu pamphlet cited above), articulating such criticism should be distinguished from engaging or sustaining a decolonial feminist praxis. A decolonial feminist praxis requires that those from the imperialising/colonising side take heed of the anti-colonial desires and directives of the colonised, rather than focusing on one's own liberation or telling the colonised how they need to liberate themselves. Thus, although EPE was in many ways inspired by a broader anti-imperialist leftist sentiment, this analysis demonstrates how such a highly transgressive and visually pioneering film can reinscribe and expose colonial modalities of being, seeing, consumption and abandonment.

Conclusion

-

Takeda and Hara's attempt to break the boundaries of the family system was staged in front of the camera as a challenge to Japanese familial imperialism. Together they produced a pioneering film that was paradigm-shifting in its representation of Japanese women's bodily agency and sexuality. Although Takeda expressed apprehension and fear of having a Black baby, in the final sequence of the film, she says repeatedly that she identifies much more with her mixed-race daughter Yu, than with her Japanese son, Rei. However, despite Takeda's attempts to express her love for her daughter, growing up in Japan, Yu experienced first hand the racism of Japanese society. Yu eventually decided to leave Japan for the US to look for her father, whom she had never met.[58] Thus despite Takeda's attempts to defy the taboos of familial imperialism, the larger structures of Japanese racism—that trouble feminism—remain to be deconstructed and transformed.

-

Through this analysis, I have attempted to illuminate the imperial intimacies of Black American soldiers and Asian bargirls through their encounters in Okinawa. EPE exposes how women's empowerment and liberation can manifest through an anti-Black logic and thereby conflict with other trajectories of liberation. This analysis provides an opportunity for further understanding of how (East) Asian non-Black epidermalisation may be articulated as a desire for racial self-recognition that does not challenge the light/white skin privilege that animates a global hierarchy of life. By studying the contradictions and limits of certain models of liberation emergent in this period, this inquiry demonstrates the need to reconsider how the limits of liberation are entangled with the intimacies of imperialism. This analysis reveals the threshold of individualist and imperialist forms of liberation, and the need to develop more collective and expansive forms of decolonial liberation praxis.

References

[1] Kokushiteki erosu: koiuta 1974 (Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974) was filmed between 1972 and 1973 and released in 1974 in Japan. The director Hara Kazuo is an award-winning leftist documentary filmmaker, known as the father of ?action documentary.? His films have been screened for decades across Japan and at various international film festivals. Produced by Shisso Productions, Tokyo, Japan. Cinéma vérité aims for an extreme naturalism, and has its origins in a style of documentary film-making. It often uses non-professional actors, genuine locations, and seeks to effect a kind of ?unbiased realism,? through nonintrusive filming techniques and frequent use of hand-held cameras.

[2] I use the term neo-imperialism to distinguish it from the pre-1945 Japanese Empire and refer to the postwar reformation of US-Japanese imperialisms in the Cold-War era.

[3] Setsu Shigematsu, Scream from the Shadows: The Women's Liberation Movement in Japan, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

[4] My concept of intimacies of imperialism draws on the work of Ann Laura Stoler, Lisa Lowe, Takashi Fujitani and Naoki Sakai. In 'The intimacies of four continents,' Lisa Lowe employs intimacy with three distinct meanings: spatial proximities and political economic logics; privacy, familial and conjugal relations; and contacts and encounters among the colonised. See Lisa Lowe, 'The intimacies of four continents,' in Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History, ed. Ann Laura Stoler, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 191–212. Building from Lowe's usage, I invoke this concept of imperial intimacies to explore racialised-sexual economies, modes of kinship and reproduction that are structured through the militarised occupation of Okinawa and maintained by Japanese and US neo-imperialisms. See Takashi Fujitani's Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011. I also draw from Naoki Sakai's emphasis on the complicities of US and Japanese imperialism. See '?Two negations: Fear of being excluded and the logic of self-esteem,' in Novel: A Forum on Fiction vol. 37, no. 3 (Summer 2004): 229–57. I also invoke imperial intimacies to illuminate the obfuscated entanglements of feminism and racism which have often remained unexplored due to way that the former is often assumed to be non-violent and the latter a form of violence. Such an analysis compels (self-)excavation, a vivisection of the conditions of imperialism, colonialism, feminism and racism that constitute the imperfect ontologies of liberation movements.

[5] Japanese names are in written with family name followed by given name. All translations are mine, except for the English subtitles from the film. I interviewed Hara and Kobayashi Sachiko on 6 May 2009 in Riverside, CA, regarding Extreme Private Eros (EPE) and Takeda's role therein.

[6] Kobayashi is Hara's partner, the producer of Shisso Productions who later became his wife.

[7] Hara Kazuo, Camera Obtrusa: The Action Documentaries of Hara Kazuo, New York: Kaya Press, 2009. Hara writes that Takeda also wanted him to film her thus underscoring their mutual desire to make the film, p. 99.

[8] See Ayano Ginoza, 'Dis/articulation of ethnic minority and indigeneity in the decolonial feminist and independence movements in Okinawa,' in this volume. I thank Ayano for offering helpful comments as I revised my article. Scholars like Hideaki Tobe describe Okinawa as subjected to a dual structure of Japanese and US colonialism. See 'Military bases and modernity: An aspect of Americanization in Okinawa,' Transforming Anthropology vol. 14, no. 1 (2006): 89–94, p. 93.

[9] Koya Nomura describes the condition of Okinawa under Japanese constitutional democracy as colonialism. See Nomura Koya, Muishiki no shokuminchi shugi: Nihonjin no Beigun kichi to Okinawajin (Unconscious imperialism: The Japanese People's U.S. military bases and the Okinawans), Tokyo: Ochanomizu Shobo, 2005.

[10] Cynthia Enloe, Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000; Gwyn Kirk and Margo Okazawa-Rey, 'Demilitarizing security: Women oppose U.S. militarism in East Asia,? in Frontline Feminisms: Women, War, and Resistance, ed. Marguerite R. Waller and Jennifer Rycenga, New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 2000, pp. 159–71; Saundra P. Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus (eds), Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia, New York: The New Press, 1993.

[11] The Women Outside, J.T. Orinne Takagi, Hye Jung Park, 1996; Camp Arirang, Diana Lee and Grace Yoon-Kung Lee, 1995; Sin City Diary, Rachel Rivera, 1992; Living Along the Fenceline, Lina Hoshino and Gwyn Kirk, 2011.

[12] Jeffrey Ruoff with Kenneth Ruoff, 'Filming at the margins: The documentaries of Hara Kazuo,' in Iris: A Journal of Theory on Image and Sound no. 16 (Spring 1993): 115–26.

[13] Hara Kazuo with Kenneth Ruoff, 'Japan's outlaw filmmaker: An interview with Hara Kazuo,' Iris: A Journal of Theory on Image and Sound no. 16 (Spring 1993): 103–13, p. 112.

[14] Hara Kazuo, Camera Obtrusa.

[15] Critical commentary about Extreme Private Eros has not provided an in-depth examination of the racial dynamics and the politics of women's sexual liberation that animate this film. See Ruoff with Ruoff, 'Filming at the margins: The documentaries of Hara Kazuo'; and Hara Kazuo with Ruoff, 'Japan's outlaw filmmaker: An interview with Hara Kazuo.'

[16] Interview with Tanaka Mitsu, 3 December 2000, Tokyo, Japan; Interview with Hara Kazuo and Sachiko Kobayashi, 6 May 2009, Riverside, California. Tanaka was a leading spokesperson who was close to Takeda.

[17] Hara, Camera Obtrusa, pp. 118–19.

[18] Ripples of Change: Japanese Women's Search for Self, Nanako Kurihara, 1993 US/Japan, 57 minutes, colour, 16mm/DVD, subtitled; Thirty Years of Sisterhood: Women in the 1970s Women's Liberation Movement in Japan, Dir. Yamagami Chieko and Seyama Noriko, 2004.

[19] Many ūman ribu activists defected from the New Left and student movements due to their sexist philosophies and organising models.

[20] Shigematsu, Scream from the Shadows, p. 112.

[21] Muto Ichiyo and Inoue Reiko, 'Beyond the new left (Part 1): In search of a radical base in Japan,' AMPO vol. 17, no. 3 (1985): 20–35; Muto Ichiyo and Inoue Reiko, 'Beyond the new left (Part 2): In search of a radical base in Japan,' AMPO vol. 17, no. 4 (1985): 51–59.

[22] According to an ūman ribu pamphlet written in 1970, a government census in 1969 counted 7,362 registered prostitutes in Okinawa. However, the pamphlet suggests there were actually twice as many. At this time, two-thirds of all labour in Okinawa was dependent on the military industry. Shiryō Nihon ūman ribu shi, vol. 1, ed. Miki Soko, Saeki Yoko and Mizoguchi Akiyo, Kyoto: Shokadō, 1992, pp. 157–59.

[23] Some ūman ribu activists did not appreciate what they deemed to be Takeda's narcissism and were critical of her. For example, ūman ribu activist Saeki Yōko wrote a critical article about the film that was published with the screenplay in 1975. Saeki writes in her article,

You can't go work at an A-sign bar where you only have Blacks as your customers, with the kind of fluffy attitude of a young university co-ed who is trying to make some extra money by working as a hostess in Ginza…. Inside a woman's head she understands that Blacks are discriminated against, and that she has some sexual curiosity to sleep with a Black man…but then [Takeda] acts like, ?Hell I dunno about that kind of thing…. I'm sure that Paul [the Black GI] went back to his country without even knowing that she gave birth to his child. Shinario Kokushiteki erosu koiuta, 1974 [Official Screenplay of Extreme Private Eros], Tokyo: Shisso Productions, 1975, p. 76.

In an interview about the film, Saeki said, ?When I wrote my [1975] article, I'm sure that I was very angry about what they did, and what Takeda wrote in that pamphlet. That's probably why I was so harsh in my article.? Saeki said, ?They were young and politically naïve; they did not understand that as mainlander Japanese women you cannot just go to Okinawa to try to experience what it's like to live as an Okinawan woman …not to mention all the political implications of working at an A-sign bar for GIs.? An ?A-sign? means that a facility has been officially ?approved? by the U.S. military. Telephone interview with Saeki Yōko, 20 February 2002. Saeki has been an active member of ūman ribu since 1971 and a key editor and archivist of the writings of the movement.

[24] Takeda had been living in a small women's liberation commune she helped establish. Later, after returning from Okinawa, she was part of an ūman ribu commune called Tokyo komuunu.

[25] A handful of ribu activists tried working in the sex-entertainment industry. See Setsu Shigematsu, 'Women's liberation and sexuality in Japan,' Routledge Handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia, ed. Vera Mackie and Mark McLelland, London: Routledge, 2014, pp. 174–87.

[26] Racism was manifest in many White feminist movements and has been critiqued by many feminists of colour. In 'Rape, racism and the myth of the black male rapist,' Angela Davis critiques white feminist anti-Black male racism. See Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race and Class, New York: Vintage, 1983, pp. 172–201. See also foundational texts such as: Cherrķe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (eds), This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, New York: Kitchen Table Press, 1984; Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott and Barbara Smith (eds), All the Women Are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies, New York: The Feminist Press, 1982.

[27] Many activists later developed and maintained long-term practices of solidarity with other Asian women from former Japanese colonies such as Korea, the Philippines and other third world nations.

[28] As note 23 indicates, an 'A-sign' means that a facility has been officially 'approved' by the US military.

[29] Yuichiro Onishi, Transpacific Antiracism: Afro-Asian Solidarity in 20th-Century Black America, Japan, and Okinawa, New York: New York University Press, 2013; Wesley Iwao Ueunten, 'Rising up from a sea of discontent: The 1970 Koza uprising in U.S.-occupied Okinawa,' in Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, ed. Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, pp. 91–124.

[30] Although practices of sexual slavery continue today, the feminists depicted here would be not be considered sexual slaves, because they clearly exert their agency in choosing this form of work. The status and relative unfreedom and immobility of other bargirls depicted invites a much larger discussion about the complex and coercive conditions of sex work, which is relevant but not the primary purpose of this paper. For one feminist analysis of sex work see, Anne McClintock, 'Screwing the system: Sex work, race and the law,' Boundary 2 vol. 19, no. 2 (1992): 70–95; Sturdevant and Stoltzfus (eds), Let the Good Times Roll.

[31] Tanaka's analysis focuses on the postwar US Occupation of Japan (1945–1952) but links his argument here to the Vietnam War period. Masakazu Tanaka, 'The sexual contact zone in occupied Japan: Discourses on Japanese prostitutes or panpan for US military servicemen,' Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, issue 31, (December 2012), para. 41, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue31/tanaka.htm (accessed 1 March 2014).

[32] William Tucker, 'Yellow panthers: Black internationalism, interracial organizing and intercommunal solidarity,' Master's Thesis, Brown University, Providence, RI, 2004. The Panther's were invited by Zengakuren and the Japanese Red Army.

[33] Onishi, Transpacific Antiracism; Ueunten, 'Rising up from a sea of discontent.'

[34] Tanaka, Mitsu, Inochi no onna-tachi e: torimidashi ūman ribu ron (To women with spirit: A disorderly theory of Ūman Ribu), Tokyo: Kawade Shobo, 1992, p. 201.

[35] Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left, New York: Vintage, 1980; Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

[36] Tanaka, Inochi no onna-tachi e, pp. 146–47.

[37] Shigematsu, 'Ribu and Tanaka Mitsu: The icon, the center and its contradictions,' in Scream from the Shadows, pp. 103–38.

[38] This emphasis on liberating the self was one aspect of a more complex concept and practice of women's liberation. In Scream from the Shadows, I argue that there was a tripartite practice of liberation articulated during the emergence of the women's liberation movement: (1) to liberate/revolutionise one's own consciousness; (2) to liberate/revolutionise oneself in relation to the other; (3) and to liberate and revolutionise oneself in relation to the larger structure of society.

[39] Sara Evans, Personal Politics; Helen Jun, Race for Citizenship: Black Orientalism and Asian Uplift from Pre-Emancipation to Neoliberal America, New York: New York University Press, 2011. Jun's analysis departs from a celebratory approach to Afro-Asian solidarity and attends to the ?less ideal, yet pervasive dynamics that are often construed as cross-racial dysfunction? (p. 4).

[40] Expressions of transpacific third-world liberation consciousness in Okinawa have been documented and analysed by Wesley Ueunten (whose article is included in this special issue). See Ueunten, 'Rising up from a sea of discontent: The 1970 Koza uprising in U.S.-occupied Okinawa.' Ueunten documents the activism and solidarity between Black GIs with Okinawans who expressed anti-US military sentiments. In the wake of an anti-US military riot in 1970 in the Koza districts of Okinawa, African-American soldiers distributed a flyer, written in English and Japanese, stating: 'The Black GIs are willing to help and talk to the Okinawans in order to form much better relations between the oppressed groups, because we have so much in common' (p. 115). Ueunten's work brings attention to the non-mutuality of such solidarity actions. He describes how in spite of such expressions of solidarity from the African American GIs with Okinawans, this solidarity was not consistently reciprocated, but that there was a predominantly hostile sentiment toward Black GIs fuelled and exacerbated by their sexual access to Okinawan women. This hetero-patriarchal approach to militarised cross-racial sexual relations is challenged by the ways that the women and feminists depicted in EPE pursue relations with Black soldiers.

[41] See Vijay Prasad, Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity, New York: Beacon, 2002; Bill Mullen; Afro-Orientalism, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004; Fred Ho and Bill Mullen (eds), Afro-Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008; Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Shannon Steen (eds), Afro-Asian Encounters: Culture, History Politics, New York: New York University Press, 2006. This body of work represents an approach that broadly celebrates Afro-Asian connections. The PMLA issue on comparative racialisation (edited by Shu-Mei Shi) also represents this interest in yellow-Black intersections. See PMLA vol. 123, no. 5, Special Topic: Comparative Racialization (October 2008), pp. 1347–815. Collen Lye's essay in the volume celebrates this shift, and articulates a desire to move away from 'the foundational status of anti-Blackness' in order that Asian Americans can 'elaborate the nonderivative nature of Asian racialization.' See Colleen Lye, 'The Afro-Asian analogy,' in PMLA vol. 123, no. 5, Special Topic: Comparative Racialization (October 2008), pp. 1732–736, p. 1733. This paper responds to the ways in which Asian racialisation remains in a triangulated relationship to Whiteness and Blackness and how anti-Black racism remains a pervasive and relevant racial dynamic.

[42] During the 1970s, the donning of Afros and copying what was imagined to be Black style was common in the club and disco scene around military bases, and in urban centres such as Tokyo. See John G. Russell, 'Consuming passions: Spectacle, self-transformation, and the commodification of blackness in Japan,' positions vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 113–77, p. 123.

[43] The White GI is not featured or seen in any significant way in this film. Throughout the film, there is only one scene where there is a glimpse of a White GI in civilian clothing walking on the street in the background. This film raises questions about the effects and impact of such cinematic exposure and how it functions to problematise and/or normalise the militarisation of sexualities. The viewer can be shocked and educated, informed and titillated, with the director/film maker at once producing a visual-epistemic field that provokes an unpredictable range of responses from the audience.

[44] Bernard Scott Lucious, 'In the Black Pacific: Testimonies of Vietnamese Afro-Amerasian displacements,' in Displacements and Diasporas: Asians in the Americas, ed. Wanni Wibulswasdi Anderson and Robert G. Lee, Piscataway NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005, pp. 122–58, p. 133.

[45] Ji-Yeon Yuh, Beyond the Shadow of Camptown: Korean Military Brides in America, New York: New York University Press, 2004; and Katharine Moon, Sex Among Allies: Military Prostitution in U.S.-Korea Relations, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

[46] This form of description without critique can serve to naturalise or normalise anti-black racism.

[47] Camptown refers to the sex-entertainment industry surrounding U.S. military bases. See Yuh, Beyond the Shadow of Camptown; and Moon, Sex Among Allies.

[48] Moon, Sex Among Allies, p. 128.

[49] Moon, Sex Among Allies, p. 129.

[50] Moon, Sex Among Allies, p. 3.

[51] In sequence four, Takeda states that she wants Hara to film her giving birth.

[52] This argument with Hara takes place in sequence seven, and the birthing scene follows in sequence nineteen.

[53] Shinario kokushiteki erosu, p. 39.

[54] Takeda attempted to run a day care for the children of Okinawan bargirls. She became especially attached to one mixed Black-Okinawan baby boy named Kenny and tried unsuccessfully to adopt him. Although Takeda wants to adopt and possess Kenny, her utterance about what kind of baby will come out of her own body signifies a latent contradictory counter-phobia of having a Black baby come out of her body. I suggest that this consumptive desire for Blackness is an expression of counter-phobia, a defence mechanism to negrophobia. This counter-phobia articulates the desire to experiment, have and possess, but not to be. Takeda's relative proximity to and intimacy with Blackness is a means to experience the other (and experience herself through the other), but she articulates a hesitation regarding the colour of her offspring knowing the prevalence of a national ideology of Japanese as the ?pure? race.

[55] My notion of an epidermal spectrum draws from Frantz Fanon's concept of the epidermal schema in Black Skin, White Masks, New York: Grove Press, 1967. In Fanon's elaboration of negrophobia, he speaks of the epidermalisation of inferiority as related to the lack of social-economic power of the colonised. I suggest that East Asian anti-Blackness is also rooted in a phobia of loss of self-racial recognition and the light/white skin privilege that is reinforced by and converges with the globality of white privilege through imperial-colonial modernity.

[56] This could be interpreted as a Japanese possessive investment in whiteness. See George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics, Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2006. After Sachiko gives birth to her baby with Hara on camera, the sequence closes with her commenting on the baby's ?pure whiteness? (masshiro). This film thus invites an analysis of racial discourse in Japanese society among leftists.

[57] This translation is taken from the English subtitles in the film.

|

Figure 2. Black GIs in Okinawa demonstrating their consciousness of Black Power

Figure 2. Black GIs in Okinawa demonstrating their consciousness of Black Power

Figure 3. A fourteen year-old Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi and an anonymous Black GI

Figure 3. A fourteen year-old Okinawan bargirl named Chi Chi and an anonymous Black GI

Figure 4. Takeda gives birth on camera in Hara's Tokyo apartment

Figure 4. Takeda gives birth on camera in Hara's Tokyo apartment

Figure 5. Kobayashi Sachiko records sound and Takeda's son Rei witness his mother giving birth.

Figure 5. Kobayashi Sachiko records sound and Takeda's son Rei witness his mother giving birth.