Close Yet Distant Relations:

The Politics of History Textbooks,

U.S. Military Bases and Trauma in Okinawa

Miyume Tanji

Introduction

I would be on the sea protesting against the construction plan even if there was no dugong in the waters. I am out in the open sea, protesting not for the environment's sake, but for a peaceful world without military bases. I cannot stand seeing Okinawa being used as a base for killing people in war.

Anti-base protester, Etsumi Taira [1]

-

The few remaining Okinawa dugongs, occasionally appearing in the sea next to the planned Marine base construction site, Henoko, symbolise the most recent phase of the Okinawan struggle. With the image of the endangered dugong at the forefront, the recent phase of anti-base struggle has taken the form of civil disobedience. The protesters on permanent encampment have physically blocked the environmental survey of the government, slowing down the construction of the replacement facilities of the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station in Futenma, planned to start in the forest of Takae Village and on the shore of the Henoko District in Nago City.[2] This development requires major land reclamation adjacent to the US Marine's Camp Schwab, in the ocean that provides a sea grass habitat and the now famous dugongs. Since the late 1990s, the political opposition in Henoko has been a round-the-clock war of attrition. In September 2009, Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio of the new government led by the Democratic Party of Japan claimed he would not build the new base in Henoko, or anywhere in Okinawa.[3] Although the fate of the new base and the Okinawa dugong is still unclear, his statement marked a major transition from the conservative Liberal Democratic Party's policy on Okinawa.

-

However, the U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gate, pro-U.S. Japanese diplomats and President Obama kept putting pressure on Hatoyama to follow through with the airbase construction plan in Henoko. In March 2010, the government unofficially sought a substitute location in Tokunoshima, an island south of Kyushu located just north of Okinawa, and met a resolute residents' opposition. Besides, the U.S. showed no interest. The U.S. kept refusing to separate the new base from other training sites of the Marines remaining in Okinawa. Henoko is located next to Camp Schwab, which is one of the major U.S. Marine Corps bases in Okinawa. On 25 April, some 90,000 Okinawans gathered in a mass rally demanding Hatoyama and the government cancel a new base in Henoko and unconditionally close Futenma Air Station (Figure 1). But the Okinawans' plea was neglected. On 2 June 2010, Prime Minister Hatoyama resigned from his post shortly after announcing his decision to construct the new U.S. Marine base after all, in Henoko, which was confirmed by the 28 May U.S.-Japan Joint Statement. He could not keep his promise during the pre-election campaign to find an alternative construction site outside Okinawa. Hatoyama's sudden turn of posture has deeply provoked the Okinawan people's anger and disappointment.

Figure 1. At the Okinawan residents' rally, 25 April 2010.

-

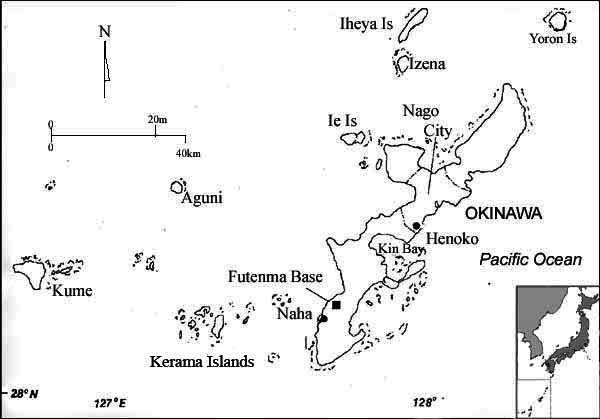

In September 2007, there was another international news item on Okinawa: a controversy on the ?correct' representation of the collective suffering of Okinawan residents in World War II.[4] More than 116,000 local protesters from across the archipelago of Okinawa challenged the government's alterations that eliminated and/or muddled descriptions of Japanese military complicity in the killings and forced suicides of the local civilian population during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa (Figure 2). The rally mobilised a greater number of local participants than any previous anti-U.S. protests.[5]

Figure 2. 2007 Rally. Source: Ryukyu Shimpo Sha, ?Shudan jiketsu' gunmei sakujo no kyokasho kentei kougi: Okinawa no Uneri (Okinawa's groundswell: protesting the textbook censorship's elimination of the military's involvement in ?group suicides'), pp. 36–37.

Figure 2. 2007 Rally. Source: Ryukyu Shimpo Sha, ?Shudan jiketsu' gunmei sakujo no kyokasho kentei kougi: Okinawa no Uneri (Okinawa's groundswell: protesting the textbook censorship's elimination of the military's involvement in ?group suicides'), pp. 36–37.

|

-

In March 2008, the Tokyo-based English language newspaper, the Japan Times, contrasted the 2007 'textbook rally' with the Okinawan citizens' rally held on 23 March 2008 'against all U.S. crimes and accidents' in response to a series of crimes, including the rape of a fourteen-year-old girl in February; only 6,000 people attended this rally.[6] The Japan Times article explains that 'history' and the 'U.S. bases' are different issues in Okinawa. Also, the population is observed to be less divided and more non-partisan in challenging the Japanese Government's policy on history textbooks. The final political statement of the organising committee does not mention the base issue at all.[7] A pictorial booklet featuring the mass protest in September 2009, published by Ryukyu Shimpō (one of two Okinawan local newspapers), has only one reference to the U.S. military.[8] Indeed, protests against textbook alterations and civil disobedience against the new U.S. military-related protests have been waged on separate public fronts.

-

Yet, considering the local anti-base protester's words quoted above, the separation of the two public issues is puzzling. Hideki Yoshikawa emphasises the symbolic significance of the dugong for the Okinawan people, connecting their significance to 'Okinawa's struggle against base construction' and 'Okinawa's experiences of World War Two.'[9] Importantly, the civil disobedience in Henoko has been more than a straightforward conservationist movement to protect the endangered dugongs and the ocean from the construction of a landfill: it is a desire that encompasses a specific historical consciousness. According to a local anti-war activist and historian Arasaki Moriteru, revisiting war in Okinawa is a 'method of anti-base struggle.'[10]

-

In order to understand why the Okinawans often separate the representation of these two political oppositions in public space, this article explores the memory of collective suffering as a trauma in the Okinawan public consciousness. Fought during the last phase of World War II, the Battle of Okinawa is remembered as one of the bloodiest of all Pacific conflicts. The island was raided and shelled by U.S. warships and some 558,000 soldiers, and almost 150,000 Okinawan civilian residents died, close to a third of the population at the time.[11] The collective suffering of the Okinawans is comparable to other events in the twentieth century, such as the bombing of Hiroshima, the Vietnam War and the Holocaust, which are more often associated with cultural and social trauma.[12] Rather than analysing responses to overwhelming events at the individual and psychological levels,[13] the discussion of 'trauma' in this article focuses on the social role played by the memory of collective suffering in defining the identity of 'Okinawa' as a political community. The interpretation of trauma, following Karl Erikson, is that: 'trauma shared can be a source of communality,' create a 'sense of identity' and 'a mood, an ethos—a group culture, almost—that is different from (and more than) the sum of the private wounds that make it up.'[14] Against this, the Battle of Okinawa can be interpreted as traumatic for the community in that it created a 'fundamental threat' to the Okinawans' sense of who they are.[15]

-

This article argues that opposition to the government's censorship of textbooks and the U.S. military presence are the same political struggle for the Okinawans. However, when tied to economic interests attached to the U.S. military presence, the interpretation of history has caused internal division. As well as bringing the people together, the trauma of their history can potentially threaten the stability of their identity. If the base issue is separated from the textbook issue, at least the residents' wartime collective suffering is represented in a way that does not destabilise the consensus on the interpretation of history that has constituted what it means to be 'Okinawan.'

-

The first section of this article reviews the significance of textbook and war memory issues for Okinawa and Japan. The second section examines how the textbook debate concerns the historical narrative of victimisation that defines the Okinawan identity, and how trauma plays a key role in continuing the narrative from the Battle of Okinawa to the post-war and contemporary periods. The third section considers how the 1999 Peace Museum debate over historiography divided local residents, and overlapped with the political division over U.S. military bases. The Museum debate became a crucial precedent that serves as a reminder that a coherent Okinawan interpretation of history is prone to internal fracture. A political front predicated on an all-Okinawan consensus was maintained by separating the textbook debate from the anti-base struggle, although the two are closely related.

War memory, history textbook dispute and the Okinawan identity

-

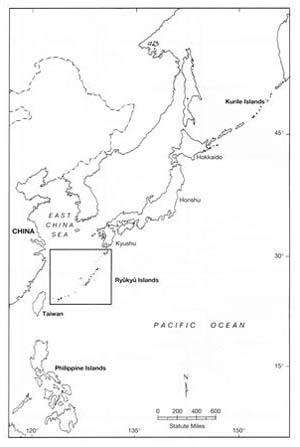

'Okinawa,' a name used in reference to this prefecture of Japan since 1879, was once a separate political entity: the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879). The Ryukyu Kingdom was a small tributary state of China, encompassing the islands in the Ryukyu Archipelago (Figure 3), including the Amami Islands (part of

|

Kagoshima prefecture since 1879) to the north and Yonaguni Island to the south. The Shuri Court on Okinawa Main Island was its highest authority. Since 1609, when the Shimazu of Kyushu invaded the Kingdom, Ryukyu was also under its rule. However, the kingdom kept nominal independence until 1879, when Japan abolished the Shuri Court and annexed the kingdom as its southern border territory. The inhabitants of Ryukyu Kingdom were neither Japanese nor Chinese. Since being annexed to the modern Japanese state, the Ryukyuan people have been regarded as sharing ethnic and especially linguistic roots with Japanese people. However, the claim to affinity with Japan was made by local and Japanese scholars and elites, strongly driven by political interests; thus, ambiguity regarding the identity of the prefecture remains.[16] Today, Okinawa is a culturally and historically distinct entity from yamato (the rest of Japan), with internally diverse island cultures.[17] Okinawa has not only been a part of Japan since 1879 but, arguably, has continued to exist as a separate nation within a bigger state.

Figure 3. Map of the Ryuku Archipelago. Source: Richard Pearson, Archaeology of the Ryukyu Islands, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1969, p. 2.

|

-

The 2007 mass protest rally in Okinawa attracted international attention that reflected the wider concern with a series of political actions, made by the conservative government of Japan at the time, to revise mainstream interpretation of World War II. Since the late 1990s, the neo-nationalists have attempted to represent Japan's military history and war in a more positive light, in a way intended to enhance pride in being Japanese. The revisionist actions included Prime Minister Abe's 'denial that the military or government hauled women away to serve as sex slaves for Japanese soldiers before and during World War Two,'[18] and official homage paid by Prime Minister Koizumi to the Yasukuni Shrine, a memorial that commemorates dead A-class war criminals as heroes. During the War, this famous shrine deifying the spirits of dead soldiers played an important role as a platform of the Shinto religion that justified Japan's overseas aggression, especially in China.[19] The official worship of the Shrine thus added tension to the Sino-Japanese relationship, provoking anti-Japanese protests in Chinese cities that included attacks on Japanese diplomatic buildings and businesses. Anxiety was shared with other nations that were invaded and colonised by Japan, including Okinawa. In this sense, the textbook protest revealed hidden nationalist tensions between Okinawa and Japan. Even the new Hatoyama government, which refused to visit Yasukuni,[20] has not changed position on the history textbook alteration.

-

But the textbook issue did not just arise in reaction to a recent surge of neo-nationalist attempts to re-evaluate Japan's war. Since the 1950s, the Japanese Government has censored history textbooks, removing descriptions that contradicted the mainstream interpretation of World War II in which Japan is a victim, rather than an aggressor. In the mid-1950s, the occupying forces' de-militarisation and democratisation of Japan 'turned around,' in order to support the U.S. Cold War anti-communist agenda. The consecutive rule of the conservative and pro-U.S. LDP leaders pushed for constitutional reform of Article 9 that bans Japan's overseas warfare and possession of armed forces, in order to legalise Japan's re-militarisation. As a result, even though the constitution itself has survived, its binding power has considerably weakened. At the same time, the Japanese Education Department has edited descriptions in history textbooks of Japan's wrongdoing or atrocities in Asian countries overseas during the war. Notably, whereas the Emperor and the people of Japan have been mainly represented as victims of the misguidance of military leaders, their complicity in promoting the war has been silenced. James Orr argues that 'victimhood' has been forged 'in the restricted contexts of discourse on personal Japanese war experiences in stories of the atomic and fire bombings, the repatriation of civilians from Manchuria and Korea, and general privations such as hunger on the home front.'[21] John Dower explains that a victimhood mentality has shaped the post-war Japanese national identity, in combination with a collective imperative towards hard work to establish economic growth.[22] Post-war Japan—mainland Japan—has sustained its national narrative of war largely through a discourse of victimhood, suppressing all references to the aggression, brutality and suffering inflicted by Japan on others.

-

However, this dominant story of the past is sometimes challenged by individuals with contradicting stories. For example, the return of Japanese soldiers who had lingered behind in various spots of Japanese invasion created confusion among the post-war Japanese.[23] The images of returning soldiers, an embodiment of Japan's aggressive past, directly confronted 'Japan-centric and victim-defined understandings of the past,' which then had to be contested and re-negotiated.[24] The Battle of Okinawa is also a significant challenge to the mainstream Japanese national war narrative that excludes other people's sufferings.

-

The role of school history textbooks has been important as a background factor in the general ignorance and amnesia amongst the Japanese public. Ambiguous textbook descriptions about past Japanese wartime atrocities across Asia give 'teachers and students the choice of discussing or ignoring the cruelty perpetrated by the Japanese military.'[25] The state's censorship has ensured that descriptions of the facts surrounding events remain unclear and innocuous. Such sanitised descriptions include the Rape of Nanjing, the state's support for forced military prostitution (the so-called 'comfort women'), the colonisation of Korea, Taiwan and the Pacific islands, and the invasions and brutal behaviours by the Japanese military in numerous Asia-Pacific locations including Okinawa. Japanese military aggression against civilians in Okinawa is a part of history that has been left ambiguous, partly because of the Japanese Government's textbook censorship.[26]

-

However, there have been attempts to write history differently. Ienaga Saburo, a history teacher, took the state censorship of his history textbook to court three times between 1965 and 1997, on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. The Ienaga trials have given Okinawans an opportunity to challenge the state's interpretation of civilian deaths. The hundreds of corrections that the Ministry of Education made in Ienaga's textbook included the rewriting of the history of Japanese military involvement in the Battle of Okinawa, when they had forced collective suicides and in some cases, had directly killed civilians.[27] The State's version is that the collective suicides of the local population were voluntary, rather than the result of orders given by the military. It was during this Ienaga trial that strong opposition by the Okinawan public to the representation of the death of Okinawan civilians in terms of voluntary sacrifice was first expressed. Partly prompted by Ienaga's trial, a phenomenal grassroots effort to record oral history from war survivors developed in Okinawa in the early 1980s. Many of these unofficial records convey personal experiences of local people and provide perspectives that do not glorify suicides as a patriotic 'sacrifice' but rather as an inevitable result of wartime state propaganda and social norms.[28]

-

The controversy remains, partly due to the 'intractability of Japan's part' played in enforcing residents' suicides.[29] The practice of committing suicide to avoid being captured can be traced back to a 1941 'code of conduct on the battlefield' (Senjinkun) that instructed soldiers not to be caught as prisoners-of-war ('Die, rather than become a POW'). Hiroaki Sato points out that this code did not literally instruct suicides; rather, it developed into the practice of gyokusai, 'to die gallantly as a jewel shatters.'[30] Gyokusai is associated with a courageous, soldier-like suicide that became culturally praised during the course of war, for example, through lyrics in popular songs.[31] Gyokusai, therefore, was not only the fate of the so-called 'kamikaze attacks' of the young Japanese pilots, used as suicide bombers on combat aircrafts, but was expected of all soldiers and, according to the government propaganda, of all civilians as well. Prime Minister Tojo Hideki made an 'emergency declaration' in February 1944, demanding '100 million gyokusai.'[32] The word also signifies the voluntary character of the suicides, which exonerates the military from using coercion to take lives. Gyokusai was practised among both soldiers and civilians, especially in the desperate losing phase of Japan's war in the Pacific islands, and on the largest scale in Okinawa. Kinjo Shigeaki, a survivor of one such group suicide on Tokashiki Island (Figure 4)—where the U.S. troops landed early in the Okinawa campaign—writes:

That day 315 people died on Tokashiki Island, equaling one-third the population of Awaren Village. People in families with grenades that failed to detonate killed each other with sickles or razors, or by bashing heads with clubs or rocks, or by strangling with rope. Those still alive hung themselves. I cried bitterly as I helped my mother to die. We were all terrified of surviving… Four in my family died—my parents, my younger brother, and my younger sister… One week earlier an army weapons sergeant came to the village office and distributed hand grenades to all the men, young and old. He issued orders that 'If you encounter the enemy, you must throw one of these at the enemy, and use the other to kill yourselves.'[33]

Figure 4. Site of group suicide; Tokashiki Island, part of the Kerama Islands. Source: Miyume Tanji, 'The Unai Method: The Expansion of Women-only Groups in the Community of Protest Against Violence and Militarism in Okinawa,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context , issue 13, 2006, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue13/tanji.html, site accessed 16 July 2009.

Figure 4. Site of group suicide; Tokashiki Island, part of the Kerama Islands. Source: Miyume Tanji, 'The Unai Method: The Expansion of Women-only Groups in the Community of Protest Against Violence and Militarism in Okinawa,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context , issue 13, 2006, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue13/tanji.html, site accessed 16 July 2009.

|

-

Gyokusai was pressed on the general public through education and the presence of military personnel in the battlefield. However, representation of suicide as a 'beautiful' act done by the civilians' own volition, even as an act done 'out of love' conveniently conceals the state's and the military's responsibility.[34] This is a favoured representation by conservative Japanese politicians and commentators, as well as ex-commanders who served in Okinawa and their families.[35] The government's textbook alterations in 2007 similarly attempted to represent the Okinawans' group suicides as voluntary patriotic acts.

'Gendered trauma in the Okinawan historical narrative of victimisation: from the Battle of Okinawa to contemporary U.S. military presence

-

Common memories about the past, shared by a substantial group of people who do not have daily face-to-face contact, play an important role in the cultural imagining of the Okinawan nation.[36] Yet collective memory, that is, 'what is "taken for granted" as true about the past'[37] needs to be distinguished from memories held by individuals. This is because the national memory that is supposedly shared by all people unknown to each other is typically represented as 'a simplistic and often uni-vocal story.'[38] Such representation also cannot avoid flattening out the 'nuance, texture and often-contradictory forces and tensions of history and politics' experienced by individuals.[39]

-

Victimisation is a key motif of Okinawan history: a common narrative that is 'taken for granted' as true about the past. There are two outstanding losses, amongst others, that contribute to this narrative: first, the loss of Ryukyu Kingdom, and second, the civilian sufferings in the Battle of Okinawa, combined with the detachment from Japan under the U.S. military rule (1945–72). These events are known as the two Ryukyu 'disposals' (Ryukyu shobun): the abandonment and marginalisation of Okinawa by mainland Japan. There is little ambiguity about the resulting subjugation imposed by Japan and the U.S. against the majority will, and as such, Okinawa's victimhood has a different quality to the Japanese wartime self-portrait. The Battle of Okinawa has thus become an important component of Okinawa's 'historical narrative of victimisation.'[40] It is a chronological narrative of loss that distinguishes Okinawa from the rest of Japan, and that marks it as a nation.

-

The Ryukyu 'disposal' did not end with U.S. military rule. After a strong mass campaign for repatriation to Japan, Okinawa became Japanese again in 1972. The Okinawan people's 'reversion movement' demanded the total retreat of the American military forces. Following the renewal of the Japanese-U.S. security treaty, however, the bases stayed in Okinawa. Also, Japan's Self Defence Forces were added to the island's already hyper-militarised environment. The reversion to Japan was arguably the fourth Ryukyu 'disposal.' Today, American military bases still exclusively occupy 18.4 per cent of Okinawa Main Island, and are 'inextricably linked with a historical narrative of victimization that stretches back to the days of the Ryukyu Kingdom.'[41] In other words, the continuing military presence also constitutes Okinawan national identity, even though expressed in terms of victimisation. Arguably, for many Okinawans the suffering of the population in World War II and the post-reversion U.S. military presence are part of a common historical trajectory that strings the stories of a nation together.

-

Okinawan history can be written as a series of events bringing collective suffering, caused by a betrayed trust in the Japanese State. As Jenny Edkins emphasises, situations that create traumatic responses involve 'a betrayal of trust': 'what we call trauma takes place when the very powers that we are convinced will protect us and give us security become our tormentors: when the community of which we considered ourselves members turns against us.'[42] In particular, the memory of war is often represented in terms of betrayal of the whole Okinawan community by the Japanese state. Therefore, betrayal is depicted in the stories of Okinawan locals who repeatedly regret following Japanese soldiers to the south in the belief that they would be protected from the U.S. Similarly, Japanese soldiers are also remembered for taking the last food supplies away from starving local families, dragging civilians out of the caves to use as shields against U.S. gunfire, and above all, for distributing grenades and indirectly or directly ordering suicides in case of imminent capture by the enemy.[43] In political discourse — for example, at the level of political protest — memory of the war is represented as the experience of betrayal. Betrayal, then, is an important component in Okinawa's trauma.

-

It is in this sense that the reversion of 1972 is remembered as a traumatic event. During the post-war U.S. military occupation, the popular movement for reversion was sustained by the hope that once Okinawa became part of Japan, it would be free from subjugation of civil and political rights and from the danger of living in proximity to military operations. It was also believed that Okinawa would be protected by the pacifist principle contained in the Japanese constitution that bans Japan from possessing military force. Most people hoped that the U.S. bases would, at the least, be decreased to a level comparable to those on mainland Japan. However, as the fourth 'Ryukyu disposal,' reversion became associated with the sense of betrayal many Okinawans' experience as a nation. Because they trusted Japan, Okinawans still live today on an island that is a U.S. garrison, where soldiers prepare and train for killing daily, and where safety and the human rights of the locals are often treated as secondary to the priority of regional security.[44] Thus post-reversion US military presence, as well as reversion itself, is a manifestation of the trauma experienced by Okinawa as a political community.

-

The group suicides of civilians are a traumatic reminder for Okinawans that it was not just soldiers who fully supported the military ethos: civilians also committed suicide and killed their own family members to escape being captured by the enemy.[45] Thus the history of group suicides challenges the orthodox war narrative that presents the Japanese people as helpless victims of the Imperial army. While it is likely that similar irrational mass suicides would have occurred on mainland Japan, had it also been invaded, it is the historical experience of civilian group suicides that distinguishes Okinawa as a political entity, with its own history and experience, from mainland Japan.[46] Okinawa has a particular war memory that forms an important part of its national identity.

-

What makes the Okinawans' war experience distinct is that they were not only directly killed or harmed, but also were forced to commit what, in retrospect, was recognised as the insane behaviour of group suicide and murder of loved ones in line with nationalist war propaganda. That is, as well as being directly harmed, the Okinawans have been doubly victimised by the bitter experience of co-operating with the state's war effort. The Okinawans still continue similar 'co-operation,' by being forced to 'host' the American military bases. This double victimhood, continuing since World War II, is what distinguishes the trauma of Okinawa from other communities living with U.S. bases. This is why, in order to understand the reasons for the 'voluntary' deaths and killings, gendered reading of forced collective suicides of the Okinawan residents is necessary.

-

This story manifests, in particular, in the collective memory of rape as a result of foreign military presence. In reference to the rape of a local teenager by U.S. military personnel in 2008, the Governor of Okinawa, Nakaima Hirokazu, commented: 'choosing between the security of the Asia Pacific region and [the] safety of a girl is not possible.'[47] The US military has constantly responded to incidents of rape by the policy of 'tightening management' of its troops, such as strengthening curfews. Yet as Okinawan women have argued, as long as the military is present in a community, rape will never cease to exist and the community can never be safe. In 1995 Okinawa, however, the 'bigger issue' of political sovereignty and the 'Okinawan struggle' of the dominantly male activists quickly obscured the bodily experience of the girl rape victim, and the need to reform the understanding of women's subjectivity and human rights in militarist societies.[48] (Angst 2001). Feminists in Korea, Bosnia and elsewhere have told of this kind of 'political exploitation of militarized violence against women': 'left to their own devices, men will take seriously sexual assaults on women only when those assaults can be used to make some other point that those men hold dear – the need for nationalist mobilization, the opposition to an unequal bilateral treaty.'[49] Misogyny and racism are essential components of military training. Inherent in the culture of militarism is aggression towards foreign women, made inevitable by the dehumanising process of combat training that enables the destruction of the lives of enemy forces and the degradation of anything female.[50] Though not openly discussed in foreign policy circles, in the areas near military posts, the safety and human rights of the people living in those areas are forfeited for the 'greater' good, which is, according to the bilateral alliance's rationale, to defend the security of the Asia-Pacific region. The continuing danger of rape and sexual violence still exists today because Okinawa has been chosen as the area of greater insecurity, away from mainland Japan. The Japanese state's neglect of the security of Okinawa continues since the Battle of Okinawa. Against gendered violence and militarism,[51] women's voices have conveyed the most powerful protest from Okinawa, 'from their experience of living in close proximity to an active foreign military.'[52]

-

Regarding such violence, an Okinawan feminist perspective reveals that there is a significant gendered dimension to the 'collective suicide' experienced by the residents during the Battle of Okinawa. Miyagi Harumi, a feminist historian of the prominent anti-military group, Okinawan Women Act Against Military Violence, stresses that it was the shame inflicted upon those who fell victim to rape by the enemy forces that forced the residents to 'voluntarily' choose 'collective suicide,' as captivity became inevitable.[53] Grenades were often given to the sons in the families, to whom assigned a task to ensure that the female members were killed.[54] The residents had been misled by particular sexual norms that blame the victim of violence, underpinned by the state's propaganda, which forced gyokusai on women and children. Thus, even if no direct order of collective suicide from any particular individual commander can be identified, it was as if an order had been made by the patriarchal ethos of the emperor, the militarist state, and the presence of Japanese army in the island.[55] Importantly, Miyagi says, the similar gender norm, namely, the shame that torments female rape victims, especially in date rape situations, continues to haunt towns near military posts today.[56]

-

The government's interpretation of the Okinawan residents' collective suicides as 'voluntary' in a purely patriotic sense thus conveniently evades the state's complicity. Such an interpretation, found in the 2007 textbook alterations, provoked in the Okinawans a fear that the state's betrayal was imminent, in the contemporary form of a continued US military presence. In this sense, the Okinawan trauma continues today, manifest in the textbook furore and the gendered reality of military presence.

-

This is why protesters in 2007 adamantly refused to recognise the governments' representation of civilian suicides as 'voluntary.'[57] The revisionist interpretation of collective suicides as a patriotic act was traumatising for Okinawans: it contradicts the inherited story of what the residents experienced in the war in Okinawa — in other words, it threatens the stability of the Okinawan identity.

Cracks in the history consensus: the effect of division over U.S. military presence

-

Considering the continuity of trauma in Okinawa, it may seem odd to an outsider that the military base issue was hardly present in the 2007 protest against the textbook alterations, as noted in The Japan Times. In Okinawa, however, it is rather obvious. For a unified protest, the U.S. military presence is too politically divisive an issue. A local political scientist surmises that the textbook issue has 'few things to do with today's interests. But protests over the U.S. military could affect problems in the real world for so many people.'[58] The recently displayed unified Okinawans' outrage against Hatoyama's broken promise indicates that Tokyo's compensation politics is losing its effect. Despite the multi-billion-yen specific budgets allocated specifically for Okinawa's economic development since 1972, Okinawan people remain the most poor and unemployed, deprived of their political and economic autonomy. The mass rally on 25 April 2010 suggests that a non-partisan consensus on opposing the relocation of Futenma Air Station to Henoko has been forming. However, when it comes to the entire US military bases in Okinawa, a similarly unified rejection has not yet been formed. If so many people's means of making a living are not so closely connected to the presence of US military bases and base-related governmental subsidies coming directly from the Ministry of Defense and the Cabinet, the Okinawans are all united in their rejection of the presence of war and militarism on their island, whether belonging to the U.S. military or Japan's Self Defense Forces. This rejection, as I argue, is the product of the memory and trauma of collective suffering of war.

-

These local interests, that is, those that will be affected by protesting against the U.S. military, are economic. Since reversion, many local Okinawan municipalities have become dependent on revenue from Tokyo's subsidies and aid for hosting the U.S. military.[59] Nevertheless, the prefecture still remains the poorest in Japan.[60] In the midst of a recent aggravated recession, the meagre local industry has no capacity to forego any base-related construction projects that realignment might cause. Nearly 75 per cent of the U.S. Forces deployed in Japan, apart from the Self Defence Forces, occupy almost 20 per cent of the small, densely militarised island.[61] Although a continued U.S. military presence on Okinawa obviously contributes to its further victimisation, it has been difficult to form a consensus of political opposition.

-

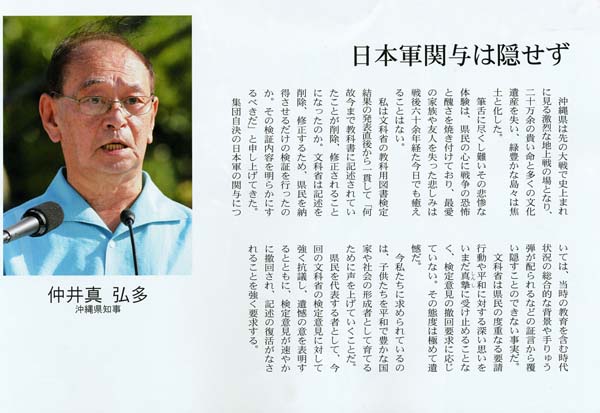

Interestingly, however, in September 2007, conservative political forces in Okinawa — led by Governor Nakaima — were willing to join in protest against the mainland government's textbook alterations, demanding correct representation of Okinawans' traumatic experience of the war. Nakaima even made a speech at the rally condemning the Japanese Government's textbook censorship (Figure 5). However, he was noticeably absent from the Okinawan citizens' rally against the US military forces' crimes and accidents in March 2008.[62] At the 25 April rally the Governor publicly made the decision to speak, only after refusing to make a commitment to do so for weeks, until the day before. Regardless of political affiliation or where one stands regarding the base issue, Okinawans share indignation towards Japan for ignoring the trauma that defines their collective identity. Nevertheless, in order to maintain a united political front based on common identity, the textbook controversy needs to be represented as a separate issue from the opposition to the U.S. military presence.

Figure 5. The Governor of Okinawa at the 2007 Rally. Source: Ryukyu Shimpo Sha, 'Shudan jiketsu' gunmei sakujo no kyokasho kentei kougi: Okinawa no Uneri, p. 26.

Figure 5. The Governor of Okinawa at the 2007 Rally. Source: Ryukyu Shimpo Sha, 'Shudan jiketsu' gunmei sakujo no kyokasho kentei kougi: Okinawa no Uneri, p. 26.

|

-

Since the late 1990s, the most controversial issue in Okinawa has been the construction of a new U.S. Marine Corps Air Station in the coastal area of Henoko, located on the north-eastern coast of Okinawa Main Island. The Japanese Government first announced the plan in April 1996, after the decision to close the Futenma Air Station, in response to the 1995 uprising of anti-base sentiment following the rape of a schoolgirl by three U.S. marines. At that time, Ota Masahide, the Governor of Okinawa, took a hard-line position regarding U.S. military bases. Ota was a history professor who had researched and documented the local memory of the Battle of Okinawa. Ota pursued 'action plans' to reduce the presence of U.S. military bases. Among his 'peace promotion' policies was the construction of the Cornerstone of Peace (Figure 6)[63] and the new Okinawa Prefecture Peace Memorial Museums in Mabuni and Yaeyama. These memorials, which attempted to represent local perspectives on World War II, were located respectively at the final site of the Battle of Okinawa (Mabuni) and in the region where residents were forcefully evacuated by the Japanese and consequently died of malaria (Yaeyama). Ota's policy had strong approval from Okinawans; according to polls in the national and local newspapers, Asahi Shimbun and Okinawa Taimusu, in May 1997 ninety per cent of the Okinawan people supported his military reduction policy.[64]

-

However, in 1998, in the face of weak economic prospects, and aggressive election campaigns backed and funded by the incumbent mainland Japanese Liberal Democratic Party, Ota was voted out and replaced by business-based candidate Inamine Keiichi. Inamine's inauguration as Governor came with a 'supplementary economic stimulus package of ten billion yen' from Tokyo, 'and later a hundred billion yen stimulus plan for northern Okinawa,' where the U.S. military facilities that were closed down in Futenma were being re-located.[65] In the following year, then Prime Minister Obuchi announced Nago City as the venue for the 2000 G8 Summit. Nago City incorporates Henoko, the designated site of a new U.S. Marine airbase. As a consequence, the Okinawa Prefecture Government's anti-base policy receded. Nago City, despite a plebiscite in 1997 revealing the majority of voters were against the relocation, announced official approval of the new military base. Consensus for a general rejection of U.S. military presence in Okinawa, reached during the Ota administration, was superseded by pragmatic, rational acquiescence.

Figure 6. The Cornerstone of Peace in Mabuni, Okinawa. Courtesy of Gerald Figal (photographer).

Figure 6. The Cornerstone of Peace in Mabuni, Okinawa. Courtesy of Gerald Figal (photographer).

|

-

The Inamine administration's focus upon economic prospects from mainland Japan seriously damaged Okinawan public support, particularly in the area of history interpretation. This arose from the new administration's tampering with exhibits in the new Peace Memorial Museums in Yaeyama and Mabuni—inherited from the previous government—to be opened in 1999. In a similar fashion to the Japanese Government's censoring of history textbooks, Inamine and his aides altered contents of the Museum that they believed would potentially offend the conservative mainland Japanese audience. Amongst other alterations, they instructed that a caption describing photographs depicting a scene of suicide be amended from 'purported death by collective suicide' to 'victims of the Battle of Okinawa.'[66] Another change was made to a diorama of a Japanese soldier pointing a rifle at an Okinawan woman holding a baby and 'ordering her to kill her baby because its cries might be heard by the invading U.S. military.'[67] The alteration removed the rifle and shifted the soldier to look like he was simply 'staring at the family hiding in the cave.'[68] These alterations obviously played down the challenge to the Japanese victim-centred narrative of war. The alterations were made in light of the anticipated rush of Japanese visitors following the G8 Summit and the need for Okinawa to appear an attractive 'resort island,' which required an appearance that reinforced mainland Japanese 'collective amnesia' of past wartime aggression.[69]

-

The debate over the Okinawan Peace Memorial Museum was largely due to a deviation—consistent with a nationalist interpretation—from the storyline regarding the nature of war. In this sense, it parallels the controversy over the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian Institute's National and Space Museum in 1995. At the Smithsonian, the exhibit provoked concern that putting a human face on Japanese casualties may eclipse the heroic and positive interpretation of the use of atomic bombs to end World War II and to save casualties—the dominant narrative of the U.S. role in the war. On the other hand, the 'history war' that was waged at the museum in Okinawa was against deviation from the Okinawan nationalist interpretation of history, which differed from the Japanese version concealing the military's aggression towards 'friendly' civilians.[70] A representation of war that did not contain something about the Japanese military's killing of Okinawan civilians was offensive to local sensibilities.

-

Additionally, the 1999 museum debate revealed divisions in the Japanese/Okinawan interpretation of history, which overlapped with divisions over the issue of U.S. military presence in Okinawa. In the following year, Inamine and his advisors criticised history interpretations that centred on victimisation. They 'praised Okinawa for making the "greatest contribution" to Japan's security of any region of Japan,' and for carrying the great burden of hosting U.S. military bases.[71] Inamine thus adopted a relativist position on history interpretation: a stance that accepts all kinds of interpretations of history.[72] In Okinawa, a relativist position on war memory is linked to an affirmative stance towards the acceptance of the new base construction in Henoko. It thus appears that the priority placed on protecting local business interests attempted to silence the trauma inherent in the Okinawan interpretation of war memory.

-

Inamine's alterations to the Peace Museum exhibits were discovered by a local committee authorised to assess the Museum's interpretative content. This led to accusations by local opposition MPs, newspapers, educators, intellectuals, peace groups and anti-base groups, who staged multiple protests over several days. 'The Okinawa Peace Network responded by mobilising its forces and framing the issue in terms of "truth" and "peace" in the name of the (Okinawan) people.'[73] Inamine apologised, and the exhibits were returned to the original design planned by the committee. The furore caused in the local media was widespread, a measure of the collective trauma experienced by the Okinawan people. In protest, some war-related items were withdrawn from the older museum collection, which included documentary evidence of 'comfort women' stationed in Okinawa under Japanese army management. The owner of these items reasoned that the collection mostly offended the Japanese government's interpretation of war, against the Governor's will.[74] Local newspapers, Ryukyu Shimpo and Okinawa Taimusu, were full of articles and letters from the readers on this subject each day, critical of the Governor's action and his revisionist interpretation of history. The coalition of opposition parties boycotted the Prefectural Assembly at the time, in addition to public protests staged by peace organisations, women's organisations and trade unions.[75] In the initial two weeks of opening, the new Museum recorded 'twice the average annual number of visitors the earlier museum had enjoyed.'[76]

Conclusion

-

The Okinawa Prefecture Peace Memorial Museum debate in 1999 confirmed the existence of desire for a collective consensus on the historical narrative that defined Okinawa as a political community. However, it also demonstrated that this consensus is fragile, in particular, regarding the representation of history when linked with the politically divisive U.S. military base issue. The Peace Memorial Museum debate was a traumatic event for the Okinawan community. It broke the structure of the Okinawan identity, splintering the collective historical consciousness. Separation of the base issue from protest against history textbook alterations was a strategic move on the part of Okinawan protesters. Consequently, in September 2007, the history textbook controversy gave expression to Okinawa's war trauma through a historical narrative of victimisation.

-

Yet representing this strategy of separation as purely pragmatic, driven primarily by economic rationalism, belies the emotional undercurrent that the Museum debate embodied: a painful recognition—although transitory—of division in the collective historical consciousness and thus in Okinawan identity. Similarly in Henoko, the internal political strife over accepting or opposing the relocation of the new Marine base 'tore up the close-meshed community life.'[77] For this reason, pro-base members of the community tend not to talk about the base issue. In general, even allegedly pro-base Okinawan residents' stance on military bases is 'ambiguous and uncertain,' affected by 'qualms of conscience' about the prolonged traumatic effects of a continued U.S. military presence in Okinawa, most often in the form of sexual violence or environmental destruction.[78] Arguably, the 1999 Museum debate laid the groundwork for the opposition shown against the Japanese Government's textbook edits eight years later. With the anti-base struggle detached from the textbook controversy, Okinawan society, rooted in a shared interpretation of history, was spared further trauma through the pain of another division.

-

Meanwhile, the civil disobedience in Henoko and Takae has continued against plans to relocate the Futenma Air Station. The opposition presented an environmentalist argument to protect the relatively pristine ocean, forest, and wildlife in northern Okinawa. Though not explicitly chanted with raised fists at anti-base protests, it is obvious to the community that the dugong culturally symbolises Okinawan identity, defined in terms of a historical narrative of trauma; one that continues from the Battle of Okinawa, through draconian U.S. military occupation, to the betrayal of reversion, followed by rape and other crimes and accidents, and also the textbook alterations. The islanders have yet to find an effective political language that represents both the history textbook debates and anti-base environmentalism as part of the same struggle. If that is achieved, it may become possible for the issue of U.S. military bases not to be detached from the traumatic memory of the war.

Endnotes

[1] Quoted in Hideki Yoshikawa, 'Dugong swimming in uncharted waters: US judicial intervention to protect Okinawa's "natural monuments" and halt base construction,' The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 6, no. 4 (7 February 2009), from: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Hideki-YOSHIKAWA/3044, site accessed 15 July 2009; Taira, personal communication, December 2007.

[2] Miyume Tanji, 'U.S. court rules in the Okinawa dugong case: implications for U.S. military bases overseas,' Critical Asian Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2008):475–87.

[3] Kyodo News reports, at a meeting with the US President Barack Obama at Pittsburgh, Hatoyama clarified that 'he has no intention of changing his "basic idea" on the issue, suggesting that he will still seek to move the heliport function of the U.S. Marine Corps' Futemma Air Station out of Okinawa Prefecture, against the 2006 bilateral accord on relocating it within the southern prefecture.' See 'Focus: Hatoyama's diplomatic skills largely untested,' in Kyodo News, 26 September 2009, online: http://home.kyodo.co.jp/modules/fstStory/index.php?storyid=461968, site accessed 6 October 2009.

[4] For example, 'Huge Japan protest over textbook,' BBC News, 29 September 2007, online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7020335.stm , site accessed 1 October 2009. Norimitsu Onishi, 'Okinawans protest Japan's plan to revise bitter chapter of World War II, in New York Times, 7 October 2007; Isabel Reynolds, 'Japan's history divide comes home in textbook row, ' in Reuters News, 19 October 2007, online: http://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUST896120071019, site accessed 1 October 2009.

[5] The population of Okinawa Prefecture is approximately 1.3 million. The figure of 116,000 protestors is an estimate of the Okinawan citizens' rally's organising committee. It surpasses the crowd at an island-wide protest in 1956, when 100,000 opposed the post-war U.S. military's construction of a base by forceful land acquisition. It is also larger than a 1995 protest following the rape of a twelve-year-old girl by U.S. soldiers, when 85,000 locals expressed their long-standing anger towards the continuing heavy U.S. military presence at a time when the Cold War had supposedly ended.

[6] Kakumi Kobayashi, 'Okinawa's U.S. ire remains low-profile: unlike history textbook issue, prefecture-wide movement not materialising,' The Japan Times, 6 March 2008. Ryukyu Shimpo (24 March 2008) reported that rain on the day was probably another reason for the low number of attendees.

[7] Ryukyu Shimpo, 30 September 2008.

[8] A member of the local opposition party, Minshuto Kenren (the Democratic Party Okinawa Branch) stated, 'Those who profit from war could not imagine the pain of the group suicide….The Okinawans must stop the construction of new military bases in Henoko, Awase Wetlands and Shimoji Island and contribute to creating peace and the beautiful planet earth,' Ryukyu Shimpo Sha, 'Shudan jiketsu' gunmei sakujo no kyokasho kentei kougi: Okinawa no Uneri [Okinawa's groundswell: protesting the textbook censorship's elimination of the military's involvement in 'group suicides'], 2007, p. 35.

[9] Yoshikawa, 'Dugong swimming.'

[10] Miyume Tanji, Myth, Protest and Struggle, London: Routledge, 2006, p. 52.

[11] Masahide Ota, Okinawa: Senso to Heiwa (Okinawa: War and Peace), Tokyo: Asahi Bunko, 1996, pp. 89–90. The number of the Okinawan residents killed, whose names are confirmed and inscribed on the monument Cornerstone of Peace, is 149,171, along with 14,009 U.S. and 77,114 Japanese dead soldiers' names, according to the Okinawa Peace Memorial Museum (23 June 2009), online: http://www3.pref.okinawa.jp/site/view/contview.jsp?cateid=11&id=7623&page=1, site accessed 1 October 2009. For a surviving resident soldier's perspective of the Battle of Okinawa, see Masahide Ota, The Battle of Okinawa [The Typhoon of Steel and Bombs], Tokyo: Kume Publishing Company, 1988; also, Hiromichi Yahara, The Battle For Okinawa, New York: Wiley, 1997; Bill Sloan, The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa, 1945 – the Last Epic Struggle of World War II, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

[12] For example, Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma, Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 2001; Janet Walker, Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003; Cathy Caruth, 'An interview with Jay Lifton' in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1995, pp. 128–47; and Georges Bataille, 'Concerning the accounts given by the residents of Hiroshima,' in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Caruth, pp. 221–235.

[13] These responses, related to post-traumatic disorder, are 'sometimes delayed, to an overwhelming event or events, which takes the form of repeated, intrusive hallucinations, dreams, thoughts or behaviors stemming from the event, along with numbing that may have begun during or after the experience, and possibly also increased arousal to (and avoidance of) stimuli recalling the event.' See Cathy Caruth, 'Introduction,' in Trauma, pp. 3–12, p. 4.

[14] Kai Erikson, 'Notes on trauma and community,' in Trauma, pp. 183–99, pp. 185–86.

[15] Jeffrey C. Alexander, 'Toward a theory of cultural trauma,' in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, ed. Jeffrey C. Alexander, R. Eyerman, B. Giesen, N.J. Smelser, Piotr Sztompka, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 1–30, p. 10.

[16] Richard Siddle, 'Colonialism and identity in Okinawa before 1945,' in Japanese Studies, vol. 18, no. 2 (1998):117–23; Julia Yonetani, 'Ambiguous traces and the politics of sameness: placing Okinawa in Meiji Japan,' in Japanese Studies, vol. 20, no. 1 (2000):15–31; Tanji, Myth, chapter 2.

[17] For example, Amami Islands, under greater influence of the Satsuma Domain since early seventeenth century, have had a distinctive identity from both Japan and Okinawa, sharing Ryukyuan cultural roots but closer to mainland Japan than the rest of the islands of Ryukyu.

[18] Linda Sieg, 'Okinawa furious at Japan's war suicide revision,' in Reuters News (22 June 2007), online: http://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUST29903020070622, site accessed 1 October 2009.

[19] In post-war Japan, state funding to Yasukuni ceased in line with the Occupation's separation of religion from politics. Visits to the Shrine by government officials are a source of controversy for appearing to affirm Japan's aggressive role in World War II. In particular, public concern has risen since the 'enshrinement of the spirits of fourteen Class A war criminals in 1978.' See Caroline Rose, 'The Yasukuni shrine problem in Sino-Japanese relations,' in Yasukuni, the War Dead, and the Struggle for Japan's Past, ed. J. Breen New York: Columbia University Press, 2008, pp. 23-–46, p. 27.

[20] 'Will Japan's global ties change?' in BBC News (16 September 2009), online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8257176.stm, site accessed 1 October 2009.

[21] James J. Orr, The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 3.

[22] John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999, pp. 29–30, 563–64.

[23] The last straggling soldier was found on the island of Lubang in the Philippines in March 1974. See Beatrice Trefalt, Japanese Army Stragglers and Memories of the War in Japan, 1950–1975, London: Routledge, 2003, p. 136.

[24] Trefalt, Japanese Army, p. 9.

[25] Yoshiko Nozaki and Hiromitsu Inokuchi, 'Japanese education, nationalism and Ienaga Saburo's textbook lawsuits,' in Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany and the United States, ed. L. Hein and M. Selden, Armonk, N.Y., 2000, pp. 96–126.

[26] Nozaki and Inokuchi, 'Japanese education,' p. 118.

[27] The number of Okinawan civilians killed by Japanese soldiers 'remain uncertain.' See Bill Sloan, The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa, 1945 – the last epic struggle of World War II , New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 307.

[28] Tanji, Myth, 2006, pp. 44–47. However, this is not to say no other such attempts were made. For example, much earlier in 1950, the Okinawa Taimusu Sha published Tetsu no Bōfū: Okinawa Senki [Typhoon of Steel: The Battle of Okinawa Chronicles], which contains detailed descriptions of Okinawan residents' experience of Japanese brutality.

[29] Hiroaki Sato, 'Gyokusai or "shattering like a jewel": reflection on the Pacific War,' in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus , 9 February 2008, online: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Hiroaki-SATO/2662, site accessed 7 July 2009.

[30] Sato, 'Gyokusai.'

[31] Sato, 'Gyokusai.'

[32] Sato, 'Gyokusai': 'Japan's mainland population at the time was 70 million, so he was also ordering Taiwanese and Koreans to meet the same fate.'

[33] Satoshi Kamata, 'Shattering jewels: 110,000 Okinawans protest Japanese state censorship of compulsory group suicides,' in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 3 January 2008, online: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Kamata-Satoshi/2625, site accessed 9 November 2009.

[34] The writer Sono Ayako uses this expression in describing a group suicide on Tokashiki Island in a book published in 1973. She argues there was no order from the commander and thus supports Japanese propaganda that they were voluntary suicides. She gave testimony accordingly at the third Ienaga Trial. See Kosuzu Abe, '"Shūdan Jiketsu" o meguru Shōgen no Ryōiki to Kōi Shikkō' [The sphere and performance of testimony regarding 'group suicide'], in Kakuran suru Shima: Jendaa teki Shiten [Islands of Disturbance: Gendered Perspectives], ed. Ikuo Shinjō, Tokyo: Shakai Hyōron Sha, 2008, pp. 25–73, p. 66, n. 2. Yet, 'many have questioned the objectivity of Sono's research, which was based on Japanese military sources and assertions by one of the garrison commanders.' See Steve Rabson, 'Case dismissed: Osaka court upholds novelist Oe Kenzaburo for writing that the Japanese military ordered "group suicides" in the Battle of Okinawa,' in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 8 April 2008, online: http://japanfocus.org/-Steve-Rabson/2716, site accessed 7 July 2009.

[35] For example, in a recent defamatory case, a famous Japanese writer Oe Kenzaburo was sued for describing the Japanese military commanders' order for group suicides of residents in Tokashiki and Zamami Islands. The plaintiffs, a former garrison commander and relatives of a late commander, argued that the Islands' residents had died for their nation of their own free will 'with beautiful hearts,' and that the suicides on Zamami had been ordered by the Deputy Mayor of Zamami Village. See Asahi Shimbun, 29 March 2008, in Steve Rabson, 'Case dismissed.' On gendered aspects of group suicides, see Harumi Miyagi, Shinban: Haha no Nokoshita Mono—Okinawa Zamami-tō "Shuudan Jiketsu" no Atarashii Jujitsu [My Mother's Last Words: Unknown Facts about the 'Group Suicide' on Zamami Island], Tokyo: Kōbunken, 2008, and Abe, 'Shūan Jiketsu o meguru Shōgen no Ryōiki to Kōi Shikkō.'

[36] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, London: Verso, 1991, pp. 5–7.

[37] Ann Waswo, 'The Pacific War in the public memory of America,' unpublished paper, cited in Trefalt, 'Japanese army stragglers,' p. 10.

[38] Duncan Bell, 'Mythscapes: memory, mythology, and national identity,' in British Journal of Sociology, vol. 54, no. 1 (2002): 63–81, p. 75.

[39] Bell, 'Mythscapes.'

[40] Glen D. Hook and Richard Siddle, 'Introduction: Japan? Structure and subjectivity in Okinawa,' in Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity, ed. Hook and Siddle, London: Routledge, 2003, pp. 1–18, p. 11.

[41] Hook and Siddle, 'Introduction.'

[42] Jenny Edkins, Trauma and the Memory of Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 4.

[43] Ota, Okinawa, pp. 111–126; see also, Tetsu no Bōfō: Okinawa Senki [Typhoon of Steel: The Battle of Okinawa Chronicles] Okinawa Taimusu Sha, 1950.

[44] Most prominently, SOFA exempts US military personnel from domestic criminal jurisdiction as well as responsibility for environmental pollution. This enables many offending US personnel to leave Okinawa before prosecution. This type of 'extraterritorial' special privilege is obviously problematic for the local population, when they are victims of crimes and accidents ranging from car crashes and arson to murder and rape. See Chalmers Johnson, Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006, p. 172.

[45] Trefalt, Japanese Army, pp. 22–23. Also in Saipan, when invaded by the U.S. before Okinawa, about 22,000 civilians died, with hundreds of thousands jumping off the cliff in July 1944.

[46] Trefalt, Japanese Army, p. 23.

[47] 'Chiji Wa "Sekando Reipu" Ken Gikai Ga Giin Hatsugen Meguri Kūten' [Governor's "second rape": prefecture parliament discussion goes round in circles], in Ryukyu Shimpo, 27 February 2008.

[48] Linda Isako Angst, 'The Sacrifice Of A Schoolgirl: The 1995 Rape Case, Discourses of Power, and Women's Lives in Okinawa,' in Critical Asian Studies, vol. 33, no. 2 (2001):243–66.

[49] Cynthia Enloe, The Curious Feminist: Searching for Women in a New Age of Empire, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, pp. 120–21.

[50] Kozue Akibayashi and Suzuyo Takazato, 'Okinawa: women's struggle for demilitarisation,' in The Bases of Empire: The Global Struggle against U.S. Military Posts, ed. Catherine Lutz, New York: New York University Press, 2009, pp. 243–69, pp. 258–59.

[51] Akibayashi and Takazato, 'Okinawa: women's struggle for demilitarisation,' p. 259.

[52] Miyume Tanji, 'The Unai method: the expansion of women-only groups in the community of protest against violence and militarism in Okinawa,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, issue 13, 2006, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue13/tanji.html, site accessed 16 July 2009.

[53] Harumi Miyagi, 'Zadankai: Sensou to Kioku, Sengo 60 nen' ['Roundtable discussion: war and peace at 60 years from the war's end'], in Okinawa Taimusu, 10 June 2005, cited in Abe, '"Shūdan Jiketsu",' p. 65.

[54] Personal communication, Miyagi Harumi, December 2009.

[55] Keitoku Okamato, Okinawa ni ikiru shisou [Okinawan thoughts that live on], Tokyo: Mirai Sha, 2007, p. 57, cited in Abe, '"Shūdan Jiketsu",' p. 55.

[56] Other suicides were forced by the wartime public ethos in Japan at the time, for example, those of kamikaze soldiers are mostly represented as 'voluntary' in the context of depicting them as war heroes.

[57] Harumi Miyagi, 'Comparative strategies to promote security for women and children,' Panel Presentation, 7th Meeting of the International Network of Women against Militarism, University of Guam, 17 September 2009.

[58] Kobayashi, 'Okinawa's U.S. ire remains low-profile.'

[59] Kobayashi, 'Okinawa's U.S. ire remains low-profile.' On economic dependency of the Okinawan economy, see Yasuhiro Miyagi and Miyume Tanji, 'Okinawa and the paradox of public opinion: base politics and protest in Nago City, 1997–2007,' in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, August 2007, URL: http://www.japanfocus.org/_Miyagi_Yasuhiro__M__Tanji-Okinawa_and_the_Paradox_of_Public_Opinion__Base_Politics_and_Protest_in_Nago_City__1997_2007, site accessed 6 October 2009; Gavan McCormack, Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, London: Verso, 2007.

[60] For example, the Okinawa Prefecture ranks the lowest in Japan in terms of per capita income, secondary and tertiary education rates, female higher education rates, local tax revenue, death rates, saving rates, manufacturing income, etc. See Okinawa Ken Kikakubu Toukeika [Okinawa Prefecture Planning Division Statistics Section], 'Okinawa no Toukei [Statistics of Okinawa],' September 2009, URL:

http://www.pref.okinawa.jp/toukeika/so/so.html, site accessed 6 October 2009.

[61] In 2009, there were 37 U.S. and 34 Self Defence Force bases on Okinawa.

[62] According to Ryukyu Shimpo, 24 March 2008, the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Foreign Affairs both clearly expressed 'relief' at the Governor's absence, and noted 'the impact is significantly reduced without the Governor's presence.'

[63] The Cornerstone of Peace Memorial constitutes a collection of marble walls with the names of over 240,000 casualties of all nationalities inscribed thereon. Figal explains that the memorial 'does stand out for breaking the usual nation-bound and patriotic modes of memorialisation,' though he reads more 'subtle ethnic and national sub-division.' See GErald Figal, 'Waging peace in Okinawa', in Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power, ed. Laura Hein and Mark Selden, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, pp. 65–98, p. 70.

[64] Julia Yonetani, 'Future "assets" but at what price? The Okinawa initiative debate,' in Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power, ed., Laura Hein and Mark Selden, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003, pp. 243–72, p. 245.

[65] Yonetani, 'Future "assets" but at what price? p. 246. This patron-client relationship has been passed on to the current Governor Nakaima, who was elected in 2006, also supported by the LDP.

[66] Julia Yonetani, 'Contested memories: struggles over war and peace in contemporary Okinawa,' complete this reference please, cited in Hook and Siddle, 'Introduction,' p. 196.

[67] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 199.

[68] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 199.

[69] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 198.

[70] Gerald Figal, 'Waging peace in Okinawa, p. 67. On revision and re-revision of the Enola Gay exhibition, see Edward Linenthal and Tom Engelhardt, History Wars: the Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996.

[71] Yonetani, 'Future "Assets",' pp. 254–55. These points were made in the 'Okinawa Initiative' papers, at the Asia Pacific Agenda Project conference in Naha, Okinawa, which attempted to 'articulate an Okinawan historical and political position more in concert with the aims of the U.S.-Japan security partnership and Japanese government policy.' See Yonetani, 'Future "Assets",' p. 246.

[72] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' pp. 201–02.

[73] Figal, 'Waging peace in Okinawa,' p. 92.

[74] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 200.

[75] Tanji, Myth, pp. 50–51; Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 200. Yakabi Osamu counted more than fifty articles on the subject in these two papers. See Osamu Yakabi, 'Kensho: Heiwa Shiryokan Mondai' [The Peace Memorial issue: an examination], in Kaeshi-kaji, vol. 25, (date), p. 18.

[76] Yonetani, 'Contested memories,' p. 202.

[77] Masamichi S. Inoue, Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization, New York: Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 175.

[78] Inoue, Okinawa, p. 125.

|