Introduction

-

It has recently been reported that the US (and Japan) have decided to move 7,000 US marines out of Okinawa. However, the impression of the Island's military presence simply being reduced is misleading. The plans for a brand-new US military offshore airbase (popularly referred to as the 'heliport') next to the Henoko village of northeast Okinawa are still ongoing.[1] Even less accurately reported is the exhaustingly long battle that the local anti-base protesters have been waging. This story goes back to the 1995 rape of a twelve-year-old local girl by three US marines from Camp Hansen, located in northeast Okinawa Island – an event that precipitated a temporary crisis of the US-Japan security alliance.[2] It was a local women's group, the Okinawan Women Act against Military and Violence (or OWAAMV) that turned it into a major political opportunity to reveal the vulnerability of the US–Japan security alliance.

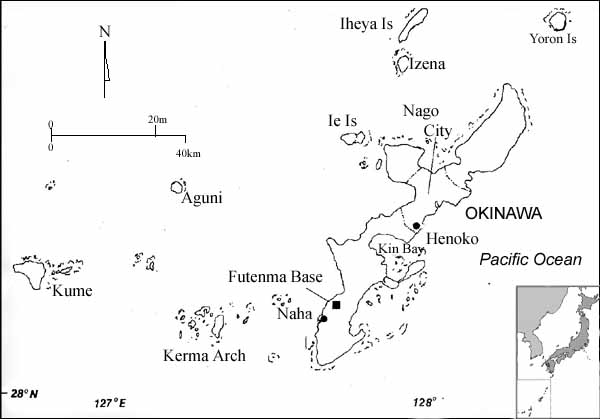

Map of the Islands of Okinawa - showing the location of Henoko, Futenma Base, Naha and Naga City.

Map of the Islands of Okinawa - showing the location of Henoko, Futenma Base, Naha and Naga City.

|

-

Political opposition to the US military presence has been a part of an older and larger struggle against Okinawa's marginal position since the dawn of modern Japan.[3] After being all but reduced to wreckage by the fierce battles of World War II, Okinawa became host to the only Marine Corps outside of the US. From 1945 to 1972, the Okinawans endured the authoritarian administration of the US forces though in the 1950s and 1960s, they engaged in a patriotic (strongly identifying with Japan) campaign for repatriation to Japan, and demanded withdrawal of the US forces. However, reversion to Japan in 1972 consolidated Okinawa as a semi-permanent depot of the US forces critical to the Japanese-US security alliance. Occupation by the US bases is still a dominant feature of Okinawan life perpetuating the unequal and excessively lenient treatment of US crimes committed against the locals. Okinawa has also suffered from structural economic dependence (due to base-related incomes), and from serious environmental degradation caused either by the bases themselves or by public works brought in by the Japanese government's base-related subsidies.[4]

-

In the post-WWII period, the idea of a coherent Okinawan people's struggle against their predicament is registered most forcefully in the work of Okinawan activist historian Arasaki Moriteru – specifically in his concept of three waves of 'Okinawan struggle' (Okinawa tōsō).[5] The first wave refers to the series of Okinawans' protest activities against draconian US land policy in the 1950s. The second wave of protest occurred at the end of 1960s. It involves a series of mass protests against the US military administration, mainly demanding reversion to Japanese administration. Traditionally protest leaders have been male anti-war landowners, left-wing political parties, the coalition of workers' unions and other citizens' groups. Importantly, they have appealed to the principles of democracy and equality promised by the post-war Japanese Constitution.

-

The third wave followed an interval of twenty five years: a period of mass protests following the rape case of September 1995. In the wake of the third wave, personal day-to-day issues, the 'protection of human rights, peace and universal human values'[6] and the environment became the main reasons for anti-base protest. Social movements concerned with environmental destruction and military's violence against civilians became as important to the 'Okinawan struggle' as the traditional focus on peace, democracy and class struggle. As a result, the community of protest in Okinawa has become increasingly fractured, plural and multi-voiced, making unified action more difficult. Women activists in particular have developed their own protest forms and styles and these are the major focus of the discussion that follows.

-

In the past decade, the island-wide explosion of the islanders' anger following the 1995 rape have given rise to a long-term, localised struggle in Henoko against the construction of the off-shore “heliport” base. The protest has been led by a small group of elderly villagers and they have attracted support from all over Okinawa, Japan and the world. This local action has involved challenging the old ways of protest: organisational hierarchy and methodological rigidity in the protest community in Okinawa. This challenge has opened up spaces for different modus operandi of political opposition that are more inclusive and that, at the same time involve more ambitious global networking. This article argues that the prominence of women-only groups and their particular brand of activism profoundly contributed to these important changes in the community of protest.

-

This article first examines how Okinawan women have established their own brand of feminism, based on the idea of Unai (guardian sisters), and its significance in the wider Okinawan community of protest. It then explains the shifts that transformed the momentary outrage of a 'rape crisis' into a new politics of protest. Importantly, the temporary all-island uprising in 1995 has shifted to long-term localised struggles most prominently in Henoko and in other towns and villages in Okinawa Main Island. The final section analyses how women-only local groups and their protest activity have influenced the 'Okinawan struggle' against the bases and against the marginalisation of Okinawans as a minority in Japan.

The Unai method

-

The everyday functions of foreign military service rely on the abuse of women's human rights through prostitution and a sex industry that specifically caters for military personnel.[7] Before the well-publicized rape in 1995, a small group of relatively well-educated, socially active women had been addressing the problem of military bases in Okinawa at the community level, as well as developing global feminist network.

- In the mid-1960s, Takazato Suzuyo investigated the burgeoning prostitution industry around the US bases and its effects on local women. In the war-torn island where everything has been destroyed, prostitution was often the only way to survive for many girls and women who had lost husbands or parents in the War. In fact, prostitution and the sex industry catering for US military personnel in Okinawa was a major industrial sector in the Okinawan economy.[8] Despite the circumstances that forced women into the industry and despite its economic importance, Okinwan society treated women who sold sex to the foreign military for a living with contempt. Many Okinawan men – who could live and go to school because of the incomes earned by women employed in the sex industry—associated the memory of local women flocking around American soldiers with the shame and misery of 'Okinawa' occupied by the US forces. Reversion and better economic times have reduced the relative size of the sex industry but they have not changed attitudes.[9] Takazato has eleven years of professional experience as a women's phone counsellor and has helped countless women suffering from ill health, economic hardship, mental distress, guilt, shame and low self-esteem caused by their experiences of rape, domestic violence and prostitution. Takazato and her like-minded colleagues have addressed the problems in 'a strange society intolerant to the prostitutes but tolerant to prostitution',[10] that is, discrimination, harassment and violence against women in the family, the workplace and the wider community.

-

As part of their routine activity, activist Okinawan women established global networks linking them to feminists elsewhere in the world. As a consequence they have participated in numerous international conferences on women, gender, and militarism since the 1985 International Women's Conference in Nairobi.

-

In 1985, the female director of a local radio network was assigned to report on the Okinawan women's attendance at the Nairobi Conference. She asked instead for a 12-hour slot of broadcasting time and a budget to make a special programme on women, to be produced by female-only staff. The radio network has since given a 12 hour-slot to a women's festival each year, and women from all sectors of the community now produce regular forums on 'women's issues'. The issues featured have included pollution, family, health, childcare, education, and work. The journalist and director who initiated the series named the event the 'Unai Festival'.

-

Unai is an ancient Ryūkyūan word meaning 'female sibling godesses' who, according to Okinawan folklore, had the power to protect male siblings from misfortune and accident. Women, for their power to communicate with gods, dominated religious ceremonies and festivals, while men only played supportive roles.[11] As a result of political influences, mainly Confucianism, the world of Unai was overshadowed by a male-dominated gender order. However, the myth of Unai is still in evidence in some remote areas today.[12] The myth of Unai was also, in a sense, re-enacted after the Battle of Okinawa, when women became breadwinners because so many men had died or become economically dysfunctional. The critical role of women in Okinawa's post-war reconstruction has been widely acknowledged. 'Unai' is a significant identity marker that makes Okinawan women 'Okinawan' no matter how globally well-connected they are.

-

In representing themselves to a larger international community of protest, Okinawan women activists have stressed their 'Okinawanness'. Takazato explains that Okinawan women are 'thinking locally and acting globally' – not the other way around. At these events, for example, the Okinawans have explained the gender issues in the context of the local patriarchal family inheritance system called tōtōme. Tōtōme limits family asset inheritance to male offspring, not only disadvantaging women's social and economic status but also discriminating women – including prostitutes—who do not give birth to legitimate sons.[13]

-

Although men also participated in and contributed to the Unai Festival events, women asserted their control on the basis of both contemporary feminist principles and a powerful ancient Okinawan myth. This has been an effective way to highlight the patriarchal social order recognised as normal at regular times. The Unai Festivals, furthermore, enabled Okinawan women to establish solidarity across differences of age, class, and regional/ethnic backgrounds within 'Okinawa'. Over the years, this general strategy sustained by myth and developed in the Unai Festivals came to be called the 'Unai method'.

-

The Unai method has also facilitated networking with women outside Okinawa. The ability to connect a local-centred approach to international action has been the strength of the Okinawan women activists. Since the 1980s, Takazato, Carolyn Francis,[14] and others developed a communication network with feminist activists, who were concerned with common problems related to gender and military bases.[15] This includes the ties with the Philippine women in the Buklod Centre in the Philippines,[16] as well as My Sisters' Place in Korea, a self-help institution for local women engaged in prostitution and service industries for American military personnel. As in Okinawa, many of these women's children were fathered by US soldiers but denied US citizenship. The Okinawan women have also exchanged knowledge and information with US feminist academics Gwen Kirk and Margo Okazawa-Rey, who set up the San Francisco Bay Area Okinawa Peace Network.[17] In 1988, women from those four countries held a joint conference on local US bases and women. The participants have since maintained regular contact in the forms of workshops and conferences.

The rise of the 'third wave' Okinawan struggle

-

September 1995 was the year the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. A team of seventy-one Okinawan women, who called themselves 'NGO Beijing 95 Forum Okinawa Action Committee', represented Okinawa. The team participated in eleven workshops, and gave presentations on Okinawan-specific topics, including 'structural military violence against women'.[18] While the delegates were attending the conference in Beijing, a girl was abducted and raped near Camp Hansen. Although this event would become the trigger for Okinawa's third protest wave, the local newspapers only reported the rape in a tiny article four days after the event when the US military refused to hand over the accused soldiers to the local police. On their return to Okinawa, the NGO Forum 95 Beijing Executive Committee and Okifuren held a press conference.[19] In contrast to the silence in Okinawa, major TV networks such as NHK, BBC and about thirty other media attended the conference and broadcast details of the rape worldwide. The women's delegation to Beijing was the first among Okinawan anti-base organizations to take public action on this rape case. After they raised their voices`, the floodgate was opened for other Okinawan protest groups. In this process, the Beijing delegates changed their name to the Okinawan Women Act against Military and Violence.

-

The women's press conference was the first public action against the rape by an Okinawan anti-base organisation. Consequently, Okinawan Governor Ōta announced that he would not sign the documents on behalf of the landowners who had refused to consent with the inspection and official documentation of their properties required for further compulsory lease to the US military.[20] Then, an estimated 85,000 citizens gathered in Ginowan Marine Park, adjacent to the Futenma Air Station on 21 October, where the Okinawa Kenmin Sōkekki Taikai [Okinawa Prefecture Citizens' Mass Rally] was held. Local newspaper Okinawa Times reported:

'This is the biggest opportunity ever to speak up for ourselves,' said the body language of the participants at the 21 October Rally … Since the All-Island Struggle in 1955-6 and the reversion movement in the 1960s, we are standing at the third turning point of Okinawan post-war history.[21]

-

The mass rally and the Governor's refusal to sign the lease contracts was a powerful demonstration of Okinawans' opposition against the US military's crimes and accidents, which had been just controlled by the Japanese government's generous financial compensation. At the 'O21' rally, the Okinawans' grievances against humiliation, daily pressure, inconvenience, danger and incursions caused by the US military presence were expressed as one 'Okinawan' voice.

-

Angst explains this idea of the rape of a girl as a violation of a body politic by foreign powers in terms of the patriotic 'trope' that requires virgin daughters to be protected by the patriarchal family/nation. And this is a figure, of course, which is problematic for feminists.[22] The purified image of the innocent girl victim is predicated on discrimination against other less innocent local women, engaged in prostitution – women raped and assaulted by US soldiers on a daily basis. Takazato also draws attention to this discrimination when it is revealed by the absence of any Prefecture Citizens' Rally for the rape and even murder of 'professional'.[23] Yet, Takazato herself has adapted a nationalist metaphor of Okinawa as 'a daughter sold to the US by Japan, for its economic prosperity'.[24] Her metaphor agrees with the language of 'sexual double standard in which raped girls are “ruined,” although it presents that loss in the name of the greater good'. Angst interprets Takazato's puzzling use of the metaphor as a strategic criticism of the state that involves 'using the very language [of patriarchal nationalism]'.[25]

-

Another interpretation is important here: the metaphor of the rape as the marginalization of the whole of Okinawa. It would be difficult for Okinawan women to be part of the community of protest, without relating rape to the historical marginalization of Okinawa. Takazato and her colleagues are feminists but they must be – or must appear to be – engaged in the struggle against marginalization of 'Okinawans', before that of 'women'. The protest voice raised by the women did enhance the international profile of the 'Okinawan' problem. To the male-dominated community of protest, women's participation was beneficial, to the extent that it contributed to keeping the myth of the 'Okinawan struggle' alive. After all, the female activists call themselves 'Unai'—a traditional Okinwan religious figure believed to protect males on their fishing trips and, in today's context, in their political struggle. By accepting the use of imagery such as 'Okinawa' as the sold daughter, the women strategically maintained a united front with other 'Okinawan' struggles.

-

Feminist argument, however, inevitably entailed confrontation with the male-oriented order in Okinawan society, and in the community of protest. Following the 1995 rape, former Okinawa Taimusu editor Yui Akiko repeatedly heard male activists' criticisms directed at the women's protest: for 'reducing everything into the problem of men's violence'; 'confusing the real issue of the US military, bases and 'Okinawa'.[26] Takazato was also abused by a male activist at a march in front of the Kadena Air Base: 'Don't trivialize things by making this all into a “violation of women's human rights”; the important issue here is the Security Treaty!'[27] Takazato reflects:

In the past, Okinawan reversion activists used to say, 'Okinawa is a pain in the little finger of the body of Japan' to describe how the suffering of Okinawans was ignored by the Japanese. But I have always wondered, in that 'pain in the little finger', how much of the women's pain has been represented? It is difficult for people to understand that women's human rights are a political issue, because there are always 'bigger' 'more important' issues. Prostitution has always been a social issue, but not presented to the public in the same way as the compulsory military occupation of land, or US plane crashes.[28]

-

The male positions briefly identified above highlight the gendered order of the Okinawan struggle. They also point to a rather conservative culture that exists in the community of protest that tends to resist new ideas. Having said this, it is also interesting to note the type of criticism Yui and Takazato heard on 'reducing everything into women's issues' is rarely heard today. Male activists in political parties, unions or informal protest groups praise the public presence and commitment demonstrated by the Okinawan women after the rape incident. They express gratitude for ways in which women 'energize' the community of protest as well as building the international profile of the 'Okinawan'—not women's—problem. 'Women' have been normalized in the community of protest; they are now 'usual suspects' at protest scenes in Okinawa.

-

Yet since the rape case, surprisingly low priority has been given to women's right to safety from sexual violence in Okinawan public policy. In 2001, REIKO, the first rape crisis centre ever in Okinawa – and a product of the lobbying of the Beijing Delegate's request – could only operate six hours a week due to insufficient funding from the Prefecture, which shrank by 650,000 yen between 1996 and 1999.[29] The OWAAMV members have continued protest activities against military violence and the patriarchal society that marginalizes gender issues.

-

Today, a highly developed division of labour exists in the community of protest. Those Okinawan activists who 'do gender stuff' in Okinawa and those who do not usually engage in separate activities. The OWAAMV members argued that it was necessary to address not just the existence of the US military base, but also the complementary relations of war, militarism, patriarchy and oppression against women.[30] Indeed, this has been the most difficult point to get across to the rest of the community of protest. But there is more to the impact of the women's movement than the new division of labour and diversification. This is best explained, however, in the context of the subsequent anti-heliport struggle.

SACO, Nago referendum and the Henoko struggle

-

In April 1996, new Japanese Prime Minister Hashimoto announced the return of the aging fifty-year-old Futenma US Marine Corps Air Base located in the middle of Ginowan City. The Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO), comprising US and Japanese diplomats and high-ranking officials, also announced the plans to return ten other US military sites.[31] Return of the Futenma Air Station was regarded as the most urgent item by Hashimoto, US officials and Ōta.[32] It epitomised the unwanted US military presence, located in the middle of crowded residential districts of Ginowan City where 84,000 people lived. Combat helicopters train and fly over this city, where up to fifty aircraft crashes have been recorded since 1972, most recently on the Okinawa International University campus in August 2004. Fifteen primary and secondary schools surround the bases, where the noise of helicopters and planes regularly interrupts classes.[33] The SACO plan of reducing US military facilities including Futenma is doubtless a response to the anti-base mass rally in October 1995 and the 'third wave' all-island struggle.

-

For the anti-base activists and locals who wished for the reduction of US military bases, the news of Futenma return, however, was a small consolation considering its condition: the construction of a new base with equivalent functions and upgraded facilities else where in Okinawa. Futenma, in other words, would be relocated rather than 'returned'.

-

In September 1996, SACO agreed on a plan to construct a 'sea-based heliport', that had been suggested by the US state officials, as an alternative facility somewhere within Okinawa. The word 'heliport' belied the scale of this alternative facility with a mile-long runway, and new accident-prone MV-22 Osprey helicopters. For this relocation of Futenma, the SACO final report designated the east coast of Nago, next to Camp Schwab, as the desirable location.[34] On this decision, Prime Minister Hashimoto commented, 'the government would not force the issue, but try to establish consensus among local municipalities'.[35] The Japanese government has also explicitly promised quick and tangible benefits for impacted local economies. As always, many Okinawan residents—although most wished to have no military bases in the island—saw these benefits as valuable. Thus, the central government has made headway by turning locals against each other.

-

One consequence of this is that the anti-base movements are being organized in different towns and villages. Today, in fact, there is no single organization to control and manage all anti-base activities in Okinawa. In the post-SACO period, the protest actors have continued to fragment into smaller and larger numbers of groups. In the post SACO period, Nago has become the major location for anti-base opposition.[36]

-

The most dedicated and determined opponents in Henoko have been the elderly members in their 80s and 90s. Their motivation stems from their experience of the Battle of Okinawa. It is not unreasonable for them to anticipate another war following the construction of a new base: they have seen it before. An elderly Henoko woman recalls the painful memories of war, and cannot bear to think her grandchildren may suffer the same in the future. Elderly people in Nago survived food shortages during and after the war by catching fish in the ocean.[37] For those who know their lives have been protected by nature's endowments in yanbaru (Okinawa Island's Northern region) the building of a major Marine Air Station in the ocean is equivalent to destroying the very source of their lives. One elderly woman comments, 'I wonder why people in the south don't oppose the construction. During the Battle of Okinawa, the southerners escaped to yanbaru and survived, because of the abundant natural resources. Their drinking water still comes from yanbaru too'.[38] Today, the elderly members in their 80s and 90s (though many have health problems) are core members of the Henoko Life Protection Society and participants in the 24-hour sit-in since April 2004.

-

As elsewhere in Okinawa, labour unions have been prominent anti-base actors in northern Okinawa. Along with collective bargaining for better working conditions and pay, it has been a central commitment of the Okinawan labour union movement to pursue 'anti-base' and 'anti-war' activities since the 1960s during the reversion movement. They were the ones who proposed a city referendum to represent Nago citizens' collective will against the heliport construction.

-

In June 1997, Nago anti-base groups formed a coalition of twenty-one organizations,[39] the Nago Citizens Referendum Promotion Council (Nago Shimin Jūmin Tōhyō Suishin Kyōgikai). The Referendum Promotion Council emphasized the importance of solidarity among parties and unions and the three citizens' movement organizations.[40] Shimin in this context signifies neutrality, non-affiliation to any political organization, and a non-ideological position. The self-definition of the coalition as a 'citizens' movement' indicates the belief that opposition and protest of citizens' organizations genuinely represent the local wishes. This emphasis is reflected in the choice of a young man—only thirty-seven years old and politically inexperienced—as chairperson of the Referendum Promotion Council.

-

Despite the importance of the citizens in the anti-heliport struggle, there are still differences between experienced members and newcomers within the coalition against the heliport. The progressive unions and political parties still play important roles in terms of mobilizing human and other resources and providing experienced advice. One of the more experienced executive members of regional workers' unions in Nago, now an anti-heliport campaigner, used to be a helmet-wearing student activist in the 1960s and believed Okinawans could get rid of the bases by reverting to Japan. He still sees the current 'Okinawan struggle' as a continuation of the reversion movement:

We are still trying to come to grips with the question, 'What was reversion all about?'; daily struggles in Okinawa are struggles against the continuing marginalization of Okinawa by the US–Japan Mutual Security Treaty, despite Okinawa's reversion to Japan and entitlement to its Constitution. Today, in the anti-heliport struggle, the role of the workers' unions and political parties should be 'supporters' of the residents in the community. On the other hand, the unions are still the main actor in the citizens' movements (shimin undō) in Okinawa.[41]

-

However, there is now less emphasis on forcing agreement. Differences are more readily accommodated within the emerging community of protest and this obviously depends on greater levels of tolerance.

Local women protest on their account

-

During the campaign for the referendum in Nago, a number of women-only groups emerged in protest against the 'heliport'. It was primarily their sense of urgency against the construction of a new heliport that motivated this rush. But something else was also involved – even if not explicitly. They were also protesting against the typically dictatorial and male-dominated modus operandi of the citizens' movements and anti-base organizations that tended to obliterate individuality and difference.

-

On the western side of Nago, during the summer of 1997, about twenty women who were campaigning for the referendum organized their own group. One of them says it was her first experience in joining any protest activity against the US military bases. When she started working with the Referendum Promotion Council members, she noticed that the campaign activities were conducted strictly under instructions given by senior male members. She also remarked that leaflets, posters, and speeches often contained language popular amongst left-wing activists in the 1970s—such as 'solidarity', 'anti-war', 'our sacred struggle'—that sounded intimidating and off-putting to younger or inexperienced citizens. She made the following suggestion:

-

Using this kind of language may scare youngsters who may be thinking about the implications of the heliport issue in their own way, and may join some kind of collective action. Why don't we try using normal language in daily conversation, for example, 'no-one will find out whether you voted for or against the heliport?' The veterans reminded me that I was only a novice, and should listen to the instructions of the more experienced members. But I was not alone. About twenty female members were feeling the same frustration. So we organized our own group, Nuchi du Takara Woman Powers' Yarukies' (Life is Treasure Spirited Women's Group) and decided to go our own way. Elite members of the Council welcomed the formation of a new women's group as an innovation that could contribute to the momentum for the referendum. The Council even gave campaign funds to the new group, and encouraged us to do whatever we wanted for the campaign, such as making pamphlets with cartoon characters and daily conversational language that looked and sounded very different from the familiar, 'progressive' style that people were accustomed to.[42]

-

Residents in Ginowan City, where Futenma Air Station is based in central Okinawa (see Map 1), see and hear helicopters and combat aircraf training daily. A female Ginowan resident has lived so close to the base that she could hear English conversations from the other side of the fence. The explosive engine noises, and neighbours' physical and psychological problems, have been part of her life, and of those close to her. In an interview she commented as follows:

When I heard the news that the Futenma would eventually close and might be relocated off Henoko, I was really angry. I was also frightened to think about the possibility that the citizens' referendum result might support the heliport construction, because of the local industrial sector's commitment to it. I felt the need to inform the local people about what it was like to live next to the US Air Force. I looked around and suggested with the people around me to do something about it together. The ones who responded were all women, about ten of us, to start with. We had no representatives or rules. The name of the group was the Gathering of Kamadu (Kamadu-gua no Tsudoi) , representing a traditional, common female name (literally meaning a big cooking pot). We did not want to use the word 'kai' (organization or group). We had never made pamphlets before but did our best and wrote down our feelings and thoughts: we didn't have time.[43]

-

The fifteen members of the Gathering of Kamadu all, by chance, female, travelled to Nago:

We did not know anyone in Nago, but we started by knocking on people's doors and explained how noisy it was to live next to the air base. The people we talked to had no idea. It was my impression that men more often than not did not have time for us. Many of them did not take us seriously, or said, 'Well, it's our turn, isn't it? In Ginowan, you have tolerated Futenma for more than fifty years. If the marine heliport is built, money will come in and the city will come to life. That's how it works. There is nothing we can do about the new base,' which was understandable because the boost in construction industry would affect their work. Women seemed to be ready to listen to us more carefully and to tell us they were worried, too.

We had day jobs on weekdays so we travelled to Nago on Saturdays and Sundays with our pamphlets. One day we had a joint meeting with the Kushi residents living north of Futami (the Jukku no Kai members). Again, attendees were all women. They said 'we are embarrassed to see that Ginowan people were working so hard in our community, while we haven't been doing anything'. So we started to hand out pamphlets and visited houses together at night after work and on weekends. In the process of hard work together, a bonding developed among us.[44]

-

Subsequently, female northeast-coast Nago residents formed a small women-only group, Jannukai (Jan is a local word for 'dugongs'). During the pre-referendum campaign, the women from Ginowan, Kushi and Nago teamed up in pairs, and made door-to-door visits. The Referendum Promotion Council evaluated the women's participation in the campaign as 'a decisive contribution to the result of the referendum'.[45]

-

Apart from the 'Yarukies', Kamadus and Jannukai, a number of other female groups outside Nago organized to discuss the base issue, and joined the referendum campaign. Many had never had anything to do with politics before the heliport issue came up, and did not know how to start a 'protest movement'. The offices of established political parties and trade unions or any 'anti-military', 'peace', 'anti-Ampo', 'anti-war' organizations seemed unapproachable to them. Those who found 'approachable' groups close to where they lived, for example, the Society of Nago Citizens Opposed to the Heliport, helped collect signatures or distributed pamphlets.

-

A Kamadu member explains that communications and team-building were easier in women-only groups because they had more in common. For example, their schedules similarly centred on children, annual rituals and family affairs. Their hand-made pamphlets were casual and informal but, unlike the stereotypical anti-base pamphlets, expressed their feelings. Their style of collective action particularly appealed to those who silently felt fearful of the new heliport and its effects, but did not have access to traditional anti-base protest organizations, or knew exactly how to express their concerns. Kamadus as a small group of 'ordinary' women not accustomed to political action appealed to other protesters: the first step taken by obviously novice protesters sent a significant signal to change the usual ways of collective action in the community of protest.[46]

-

The increasing activism of so-called 'ordinary, inexperienced women' was enormously significant. Women had always been present in the 'Okinawan struggle', both during the 1950s land struggle and the reversion movement. In the Okinawan community of anti-base protesters, however, women generally played supportive roles as wives and secretaries of male protesters. A typical woman's role would be to make tea and prepare meals in the protest office. Activists' wives also contribute to their husbands' protest by doing even more housework, part-time work and child-rearing than usual so that their husbands could focus on their protest activities until late in the night and on weekends. Most women accepted simply accepted these roles.[47]

-

These newly formed, female-only groups have not explicitly expressed a feminist message, apart from saying 'we are concerned with the construction of a new base from a woman's perspective, as mothers, for our children'. Implicitly, at least, they appear to rely on an essentialist image of women. When they are given a public presence, Okinawan women activists are often represented as 'mothers', or romanticized carriers of primordial religious aspects of life closer to nature, removed from war and military bases and so on. Indeed, during the campaign against the heliport women's messages as mothers against the new base construction were exploited by male activists, and were frequently used during the referendum campaign. One member, who also joined the referendum campaign as an 'ordinary, inexperienced activist' and a mother, says, 'These days, when I hear the word 'mother' in relation to the base issue, I feel instantly exhausted; I feel my 'motherhood' is being used'.[48] The gendered power relations and the role of women in subordinate positions within anti-base organizations had not become a major, public or politicized issue.

-

The referendum was held on 21 December 1997. The majority – 54 per cent – of Nago residents voted against the heliport construction.[49] Despite this Nago Mayor Higa officially approved the heliport construction in Henoko several days later—on the condition that the state provide special assistance for the local economy. He resigned three days later on 24 December. The referendum result, earned by hard work and democratic procedures, was simply set aside by state power. This event dealt a body blow to those who had campaigned in opposition and made for a dark chapter in the history of the Okinawan anti-base struggle.

-

Nevertheless, during the anti-heliport struggle, the anti-base women stepped into a new realm of collective action, closer to home: the gender politics of the community of protest itself. Initially, women would express their positions in casual comments such as, 'We cannot leave this to the men any more'. Forming female-only groups separately was an act of 'saying sayonara' to a male and seniority-dominated anti-base organization, without explicitly engaging in confrontation. Organising female-only collective action was itself often a sufficient political statement.

-

The value of this approach and of the Unai method was clearly demonstrated during the anti-heliport struggle. Immediately before the referendum, women's groups from all over Okinawa engaged in a joint activity. As the pro-base group's campaign was becoming increasingly aggressive, the Kamadu and annukai members planned a rejuvenating demonstration (michi-junay) which looked like a traditional Okinawan dance performance on the street. They were initially worried about how many people would turn up and were deeply gratified and encouraged when the 'Yarukies' and OWAAMV and women's groups outside Nago came to join them. The occasion was very special and led to the formation of an Okinawan-wide women's network – 'Reach to the Heart Women's Voice [Kokoro ni Todoke Onna-tachi no Koe] Network'.

-

Takaesu Ayano, a female coffee shop manager from southern Okinawa says, 'I could not just watch these women. They really sounded like they were personally addressing me, “Let's do this together”'.[50] She contacted her female friends in Okinawa and in mainland Japan, and raised funds for a newspaper advertisement announcing women's opposition to the heliport construction. The Network continued organizing humorous and inspiring collective action in Naha and Tokyo.[51] The Unai method of these women claimed it was all right to have no experience in political activism or not to belong to an established organization. Doing effective political work—even with others who had different backgrounds and opinions—required most importantly passion and ideas and tolerance. This has significantly lowered the barrier existing between the established anti-base organisations and politically non-involved but concerned individuals.

-

Partly because of the (physical and psychological) distance between northern and southern Okinawa, and partly because of the emphasis on localism, participation in the anti-heliport in Nago campaign has not always been easy for those who live in other parts of Okinawa. Women's groups crossed these barriers and developed inter-regional bonds. The Unai method has further encouraged non-affiliated male individuals who wished to act, using their original ideas and energy, rather than relying on well-established organizations. The greatest advantage of the individual-based protest is the freedom from the need for lengthy consensus building (need to have proper organizational meetings, need to discuss with other members. etc), which allows quick decision-making and timely actions.

-

The Unai method is present in the activities of those who are committed to foregrounding the theme of environmental protection such as the members of Jukkuno Kai (of ten small districts) in Nago's northeast coast region.[52] The aforementioned female Jannukai members have been also central Jukkuno Kai members. Much younger than most of the Henoko Life Protection Society members, Jukkuno Kai members were also more pressingly confronted with the issues of how to make a living and developing an industry in a rural economy without state-funded public works, rent from the military or special subsidies tied to military bases. As elsewhere in the region, agriculture was shrinking and the younger population was moving away. 'Nature' was the only special asset they had. Since a dugong was witnessed off the coast of northeastern Okinawa during the state's preliminary inspection of the planned 'heliport' construction site in May 1997,[53] Jukkuno Kai members have campaigned for dugong conservation as part of the protest against heliport construction. More dugongs have been witnessed since then. The Okinawa Dugongs – enjoying world heritage status – have boosted pride in the local-specific natural asset of yanbaru. The dugong conservation campaign has made it possible to link with environmentalists in Naha, mainland Japan and overseas. The dugongs now seem to be doing their share of work in the campaign to stop a huge military facility in their habitat. The whole Nago anti-heliport community embraced Okinawa dugongs and they have become an icon, a logo appearing on the pamphlets, signboards, and t-shirts to oppose the heliport.

-

Okinawan delegates lobbied for the conservation of Okinawa Dugongs at the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Conferences held in Amman, Jordan in 2001 and Thailand in 2004. With the support of other English-speaking environmental NGOs, they successfully obtained an IUCN resolution, which recommended the US and Japanese governments introduce steps to protect dugongs.[54] The international publicity given to Okinawan dugongs, following a series of lobbying initiatives and international conferences on sea mammals and coral reef has alarmed many US-based environmental NGOs.[55] The Centre for Biological Diversity, with a coalition of US and Japanese environmentalist NGOs, filed a lawsuit in San Francisco District Court and asked the US Department of Defense to comply with the US National Historic Preservation Act.[56]

-

This news was reported with enthusiasm at the protest encampment site in Henoko. The protesters' round-the-clock sit-in in Henoko has continued unbroken since April 2004, led by the elderly Henoko Life Protection Society members, and various supporters who have physically blocked the drilling surveys for the heliport construction. Nothing is built yet, and Futenma Air Base has not moved.

Conclusion

-

In Okinawa, women have always engaged in political activities. Somewhat distanced from the mainstream struggle focused on Okinawa's marginalisation by Japan and the US, Okinawan feminists have highlighted 'women's specific oppression in relation to men [to prevent] this from being submerged.'[57] In this framework, the problems of US military bases in Okinawa have been understood and defined as part of a global gender issue. They have developed a brand of feminism linked to the local myth of 'Unai', and built networks with women in other places within Okinawa and globally. In terms of public debate on gender discrimination and women's status in Okinawan society, the temporary spotlight on the OWAAMV members' role in leading the third wave Okinawan struggle made only a limited difference. Namely, it has not necessarily meant the dramatic improvement in awareness about women's issues and gender equality in Okinawa. Nor has it merged the women's movement and the 'Okinawan struggle'.

-

However, in the subsequent phase of the anti-base protest in Henoko, the newly formed women-only anti-base protest groups have significantly contributed to the change in the dynamics in the Okinawan community of protest. The 'ordinariness' of these women had a special appeal to the general public. Their concern with the heliport—expressed in informal, everyday language—had the poignancy that the highly organised, experienced activists no longer conveyed. During the anti-heliport struggle, women's groups and the Unai method have become normalised. Although the Henoko anti-heliport struggle has never been explicitly about women's issues, female-only collective action has had enormous implications for changing the nature of protest.

-

Subsequent protest actions of the Okinawans have become increasingly swift, individual action-oriented, supported by a loose network and NGOs, and globally influential. Today, the protest tent pitched on the Henoko waterfront is the centre of popular protest. The spiritual leaders are the elderly Henoko villagers. But it is also a global struggle joined by many: mainland Japanese 'migrants' obsessed with dugongs, Greenpeace's Rainbow Warrior crew, and American environmentalist lawyers who took the case for Okinawan Dugong conservation to the San Francisco District Court against Donald Rumsfeld, for example. The landscape is quite different from the traditional image of an 'Okinawan struggle' (that, is again, the united island-wide mass protest demanding democracy and equality justified by post-war Japanese constitutional rights). Women-only protest groups, by exploring more democratic and equal ways of conducting protest activities, facilitated building a kind of solidarity not orchestrated by the idea of unity.

Endnotes

[1] For example (2005), 'US to cut Okinawa troop numbers,' on BBC News World Edition, 29 October, online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4387660.stm. For a comprehensive coverage on the new off-shore base, see 'No home where the dugongs roam' (2005), The Economist, 27 October.

[2] Y. Funabashi (1997), Dōmei Hyōryū [The Drifting Alliance], Tokyo, Iwanami.

[3] The islands of Okinawa were under the rule of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, until 1879, when the Kingdom was abolished and annexed by Japan. The annexation was part of Japan's attempt to define the boundary of the unified nation-state in the late nineteenth century.

[4] For example, see G. McCormack (1998), 'Okinawan Dilemmas: Coral Islands or Concrete Islands?' JPRI Working Paper, No. 45, URL: http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp45.html, 2 August 2006.

[5] M. Arasaki (1999; 2nd edition 2000), 'Okinawa Tōsō – sono rekishi to tembo' [The 'Okinawa Struggle': history and prospect], in Okinawa o Yomu [Reading Okinawa], Jōkyō Shuppan Henshūbu (ed.) Tokyo: Jokyō Shuppan.

[6] M. Arasaki (1997), Heiwa to Jiritsu o Mezashite [Towards peace and autonomy], Tokyo: Gaihōsha, p. 166.

[7] See C. Enloe (1990), Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics, Berkeley: University of California Press; K.H.S. Moon (1997), Sex Among Allies: Military Prostitution in US-Korea Relations, New York: Columbia University Press.

[8] Indeed by 1970 prostitution replaced sugar as Okinawa's largest industry with earning of some $US50.4 million while sugar lagged behind in second place at $US43.5 million. See S.P. Sturdevant & B. Stoltzfus (1993), Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the US Military in Asia, New York: New Press, pp. 251-52.

[9] With Okinawa's reversion to Japan, legislation against prostitution was introduced. Nevertheless, the sex industry around the bases continued with migrant workers predominantly from the Philippines, who were often trafficked into Okinawa illegally through underground crime syndicates. For more details, see Sturdevant & Stoltzfus, Let the Good Times Roll.

[10] S. Takazato (1996), Okinawa no Onnatachi: Josei no Kinsen to Kichi Guntai [Women in Okinawa: Women's Rights and the U.S. Military Presence], Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, pp. 106-11.

[11] See, for example, S. Sered (1999), Women of the Sacred Graves: Divine Priestesses of Okinawa, New York and Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

[12] E. Asato (1999), Ryūkyūko no Seishin Sekai [The spiritual world of the Ryūkyū Arc], Tokyo: Ochanomizu Shobō, p. 130.

[13] S. Takazato (1995) 'The past and future of Unai, sisters in Okinawa,' in AMPO – Japan Asia Quarterly Review (ed.) Voices from the Japanese Women's Movement, New York: East Gate, pp. 74-79.

[14] Francis has lived in Japan as a Christian missionary since 1968 and she had worked for women's rights in Japan. Since 1989, she has lived in Okinawa and engaged in activities for peace, writing about base issues and women's issues in Okinawa. See C.B. Francis (1999) 'Women and military violence' in Okinawa: Cold War Island, ed. C. Johnson, Cardiff, CA: Japan Policy Research Institute.

[15] For example, G. Kirk & M. Okazawa-Rey (1998), 'Making connections: building an East-Asia – US women's network against US militarism', in The Women and War Reader, ed. L.A. Lorentzen & J. Turpin, New York and London: New York University Press.

[16] They visited after Mount Pinatubo erupted in 1991, and saw the economic hardship of the residents in Olongapo City after the Subic US Navy Base was closed and returned to Philippine control. Subsequently the Okinawans sent sewing machines to the local women – some of whom formerly operated as sex workers around the Base – to help them to obtain income by making and selling clothes. Since then small groups of female and male Okinawans have frequently visited the Buklod Centre in the Philippines. See Takazato, Okinawa no Onnatachi, pp. 168-69.

[17] See G. Kirk, M. Matsuoka, & M. Okazawa-Rey (1997), 'Women and children, militarism, and human rights: international women's working conference,' in Off Our Backs: a Women's News Journal, October, vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 8-9, 17-19.

[18] Other topics were: 'The environment and women', 'Ūji zome' [traditional dying as an example of sustainable local-oriented industry, using sugar cane], 'Structural violence against women', 'Comfort women (during WWII) in Okinawa', 'Action against nuclear weapons', 'War and malaria' (during WWII, especially in the Yaeyama region), 'Women and peace panel exhibition', 'Traditional culture and gender discrimination', 'Aging society and welfare', 'Women and labour', 'The Unai network'. See NGO Forum Beijing 95 Okinawa Jikko Iinkai, 1996.

[19] What motivated them to quickly publicise this case was the rape case that had occurred two years earlier of a nineteen-year-old local woman, who was abducted, driven to the base and raped by a US soldier. It was only after the soldier left the country after having been charged that the local newspaper reported the case. Four months later, the victim dropped the case, due to the shame and isolation. As a result, the rape might not even remain on the criminal record of a discharged soldier. Because rape and sexual violence are recognised as a shame, rather than a human rights violation, the journalists and police either silence or scandalise the subject. The rape victims needed to obtain public support immediately, which required more than the request of enhanced discipline to the US Consulate and the Defense Facilities Bureau. See Takazato, Okinawa no Onnatachi, pp. 22-25.

[20] His signature was necessary to authorise the state's compulsory lease of the anti-war landowners' properties to the US military for the terms that were about to expire in May 1997 and March 1996.

[21] Okinawa Times, 22 October 1995.

[22] L.I. Angst (2001), 'The sacrifice of a schoolgirl: the 1995 rape case, discourses of power, and women's lives in Okinawa,' in Critical Asian Studies, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 243-66, p. 262.

[23] Interview with Takazato Suzuyo, Naha, Okinawa, March 1999.

[24] Takazato, Okinawa no Onnatachi, p. 28.

[25] Angst, 'The sacrifice of a schoolgirl', pp. 252, 261

[26] A. Yui (1999), 'Josei no shiten kara' [From women's perspective], Okinawa Hōsei Gakkai Kaihō, vol. 11, no. 31, March, p. 14, emphasis added.

[27] Takazato, S. (1995) 'Enough is enough!' in AMPO Japan-Asia Quarterly Review, vol. 26, no. 3, p. 3.

[28] Interview, Takazato Suzuyo, Naha, March 1999.

[29] REIKO (Rape Emergency Intervention Counselling Centre Okinawa) (2001) 'Goshūnen tokushūgō' [Special Issue: 5th year Anniversary], in REIKO News, 5 April, p. 16.

[30] For example, H. Miyagi (2000), 'Guntai wa 'josei' no teki desu — “shuudan jiketsu,” gōkan to Okinawa no josei,' in Okinawa o Yomu [Reading Okinawa], Tokyo: Jōkyō Shuppan.

[31] The plan included the relocation of the live fire training range across Road 104 in Kin Town, the 'drop' training site (using parachutes) in Yomitan village and the Naha Military Port. These particularly hazardous facilities for the locals had been considered urgently in need of some kind of resolution. In April 1994, the Director General of the Japanese Defense Agency demanded the US Secretary State work for resolution. However, no progress had been made, 'until the Secretary of State Perry received a wake-up call by the 1995 rape incident.' See Funabashi, Dōmei Hyōryū, p. 351.

[32] The final report stresses that the US and Japan have responded to the Okinawans' anti-US base feelings, by making a dramatic change in the US military presence: 'approximately 21 per cent of the total acreage of the US facilities and areas in Okinawa excluding joint use facilities and areas (approx. 5,002 ha/12,361 acres) will be returned.' See Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, U.S. Department of State (1997, August 5) SACO Final Report, online: http://www.state.gov/www/regions/eap/japan/rpt-saco_final_961202.html, accessed 26 September 2005.

[33] H. Fukuchi (1996), Kichi to Kankyō Hakai [Military bases and environmental destruction], Tokyo: Dōjidaisha, pp. 21-22, 52-54.

[34] There were three major location sites for the heliport. The Kadena Ammunition Storage area was the first and it was opposed by three local assemblies of Chatan town, Kadena town, and Okinawa City jointly opposed (Ryukyu Shimpo, 17 September 1996). Another site was Nakagusuku Bay, adjacent to a US navy port (known as the White Beach). Likewise, residents in Katsuren town and Tsuken Island next to White Beach expressed clear opposition to the plan, due to anticipated effects of the 'heliport' on the local fishing industry (Ryukyu Shimpo, 25 September 1996). These two possibilities were scrapped for various reasons, including the staunch residents' opposition.

[35] The Okinawa Times Weekly, Monday Evening Edition, 9 December 1996, emphasis added.

[36] Nago City (with a population of 57,434 in 2004) is a major city in Okinawa Island's northern region, which covers a vast area from Kin Town and Onna Village to Kunigami Village, an area that Okinawans call 'yanbaru' [mountain and forest] (Map 1).

[37] H. Higa, E. Shimabukuro & T. Shimabukuro (2000), 'Henoko no Umi wa Inochi no Haha' [Henoko's ocean, the mother of life], in Kaeshi-kaji, vol. 26, March, p. 40. Some Henoko residents still make a living out of fishing in the ocean next to Camp Schwab, watching the US amphibious tanks coming in and out of the ocean. In the reef area, because of the red soil contamination, fish have greatly decreased.

[38] Higa, et al, 'Henoko no Umi wa Inochi no Haha', p. 40.

[39] Member organisations were the Okinawa Socialist Masses Party (OSMP) Nago Branch, Okinawa Social Democratic Party (OSDP) Nago Branch, Japan Communist Party Northern Regional Committee, Komei Party Nago Branch, the Okinawa Prefectural Labour Union Committee Northern Branch, Rengō Northern Co-operation, Jichirō [All Japan Prefectural and Municipal Workers' Union], Northern Headquarters, Jichirō Nago City Hall Workers' Union, All-Medical Doctors' Union Okinawa Airakuen Branch, Okinawa Peace Movement Centre Northern Branch, and the One-tsubo Anti-War Landowners' Organization Northern Bloc. Other members included the Nago City Peace Committee (a branch of a nation-wide franchaise and an off-shoot of the Japan Communist Party), the New Japan Women's Association Nago Shibu [NJWA], and 11 Nago City Assembly's anti-base members representing progressive political parties (Nago Shimin Tōhyō Hōkokushū Kankō Iinkai, Nago Shimin Tōhyō Wōkokushū: Nago Shimin Moyu Arata na Kichi ha Iranai [Nago Citizens' Plebiscite Report: Nago Burning, No More New Base], Nago, Okinawa: Kaijō Heli Kichi Hantai Heiwa to Nago Shisei Minshuka o Motomeru Kyōgikai, p. 75).

[40] Nago Shimin Tōhyō Hōkokushū Kankō Iinkai, Nago Shimin Tōhyō Hōkokushū, p. 87.

[41] Interview, with a member of the Regional Workers' Unions in Nago, Nago, February 2002.

[42] Interview, with a member of 'Yarukies', Nago, February 2002.

[43] Interview, with a member of Gathering of Kamada, Ginowan, May 1999.

[44] Interview, with a member of Gathering of Kamada, Ginowan, May 1999.

[45] Nago Shimin Tōhyō Hōkokushū Kankō Iinkai, Nago Shimin Tōhyō Hōkokushū, p. 59.

[46] Interview, with a member of Gathering of Kamada, Ginowan, May 1999.

[47] Wives of anti-war landowners and anti-base activists discuss their experiences in K. Ikehara, Y. Chibana, K. Sakima & K. Matayoshi (1996), 'Onnatachi no Hansen Undō: Kahchan no tatakai' [Women's Anti-war Movement: Battles of the Mothers], in Kaeshi-kaji, vol. 12, September, pp. 38-43.

[48] Interview, with a member of 'Yarukies', Nago, February 2002.

[49] In total, 82.45 per cent (31,477 votes) of the eligible voters cast their votes. The breakdown of the votes was: 1) I agree with the construction plan – 8 per cent, 2) I agree because the environmental measures and economic improvement can be expected – 37 per cent, 3) I oppose the construction plan – 52 per cent, 4) I oppose because environmental measures and economic improvements cannot be expected – 1 per cent, 5) Invalid – 1 per cent.

[50] Interview, with Takaesu Ayano, Sashiki, May 1999

[51] In January 1998, the Reach to the Heart Women's Voice Network met Ōta at the lobby of the Prefecture Hall, and asked him not to accept the new base. This was a spectacular event, with the lobby filled with 300 women. Governor Ōta had made difficult decisions to mend relationships with Tokyo, to save the local economy from its subsidies drying up, by being more moderate on the base issues. Subsequently, Ōta readjusted his position on the heliport, and expressed his opposition officially, even though the connection of the two events was unclear. Following this, the Network members did a michi junay in the streets of Ginza in Tokyo. They made it into a performance of a sale of the new base, with the premium of Government's special subsidies, in a tarai [washing basin], playing a pun on tarai mawashi [passing from one place to another] of Futenma Base. As of 2005 the Network is still active. In July they did another michi junay in Naha.

[52] See C. Spencer (2003), 'Meeting of the Dugons and the Cooking Pots: Anti-Military Base Citizens,' in Japanese Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 125-40.

[53] Dugongs are endangered, large marine mammals, still occasionally found off the coasts of northern Okinawa. They are an endangered species, which used to live throughout the Okinawa region. 'Disappeared from elsewhere in Okinawa, the current distribution of the dugongs is only along the northeastern coast of the main island of Okinawa, and the number is thought to be very small, possibly less than 50 animals' (Save the Dugong Campaign Centre, (2003) < a href="http://www.sdcc.jp/E/dugongnow.html ">">' Dugongs are being endangered,' online: http://www.sdcc.jp/E/dugongnow.html,> accessed 26 September 2005).

[54] See World Conservation Union (IUCN) (2001) 'Conservation of Dugongs, Okinawan Woodpecker, and Okinawa Rail on and around Okinawa Island,' online: http://www.iucn.org/amman/content/resolutions/rec72.pdf, accessed 26 September 2005.

[55] The Center for Biological Diversity (2 July 2004) reports that, '889 of the world's leading coral reef experts from 83 countries participating in the 10th International Coral Reef Symposium in Okinawa, Japan, have signed a resolution calling on the governments of Japan and the United States to immediately abandon their joint plan to construct an offshore airbase atop a coral reef on the eastern coast of Okinawa.' See 'World's Leading Coral Reef Experts Voice Opposition to U.S. Military Airbase Project at Henoko, Okinawa and Highlight the Threat that Land-fill Projects pose to Coral Reefs,' online: http://www.sw-center.org/swcbd/press/coral6-2-04.html, accessed 26 September 2005.

[56] The National Historic Preservation Act 'requires agencies of the US government to conduct a full public process before undertaking activities outside the United States that might impact the cultural and natural resources of other nations'. The lawsuit was represented by a non-profit public-interest law firm, Earthjustice. In March 2005, the judge's verdict ordered the Department to comply with the Act and investigate the 'extent of harm the proposed airbase will cause' the Okinawa dugongs.' See U.S. Newswire, 2 March 2005.

[57] S. Rowbotham (1992), Women in Movement, New York and London: Routledge, p. 6.

|