A Brisbane Multicultural Arts Centre National Travelling Exhibition

JOAN G WINTER

INDEPENDENT CURATOR, BABOA GALLERY

-

Talking Tapa: Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland offers grace in a complex, complicated world. Its genesis was simple. I was introduced to the tapa collection at the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum.

| |

I found it staggeringly wonderful for such an ad hoc collection. I already knew the Queensland Museum's collection was large. I had my own tapa collection and knew many Pacific Islanders in Brisbane. I knew that little to nothing was taught about Oceania in our schools. I understood that the aesthetics of tapa design across the Pacific had a very contemporary aesthetic feel. And, perhaps most significantly for gaining funding support, I knew that the current migration of Pacific Islanders to Queensland had surpassed the Sudanese refugee influx, and become the largest group currently migrating to Australia. So, all of this constituted a rationale for a timely show.

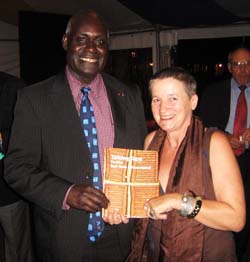

Figure 1. Paul Neyau, PNG Consul (Brisbane) and Joan Winter at the opening of the Talking Tapa exhibition in Brisbane.

|

-

The actual objects acquired for Talking Tapa are important on many levels, but not as important as our Pacific Islander peoples and their uses of their tapa in the diaspora in which they now live, in increasing numbers in Queensland. Talking Tapa is about thinking globally or oceanically and acting locally, in Brisbane, Queensland. The show demonstrates the strong relationship between object, object provenance, place and cultural practice. While the exhibition loans were distributed between the Queensland Museum, the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum and community loans, community engagement and stories that were told in company with the objects, were central to the show's warmth, spirit and success.

-

Tapa connects and journeys, engenders social cohesion through the touchability of its material and its symbolic potency, in both its places of origin and in the diaspora in Australia. Tapa is an integral part of an astonishing level of activity in Australia, as it criss-crosses suburbs, cities, regions and states, for Tongan, Samoan and Fijian communities in particular.

-

Though seemingly an inanimate object, tapa is in fact imbued with life. It has a role in many phases of life and thus becomes animate. In the way of all significant cultural markers it transforms and enables. In pre-Christian Fiji a fine very long white masi (tapa) hung down from the central pillar of the priest's house to where he sat on the floor, thus enabling the gods to descend and communicate with him, transforming his secular worldly realm. Today tapa is equally, if differently, transformative as the development and tour of the show indicates. The animating spirit of tapa in the Talking Tapa show has made Fijians in particular smile, get goose bumps and talk about loving their culture all over again in provincial Queensland. It has invigorated people and engendered liveliness in parts of the Pacific community and even raised some spirits from the dead.

-

I will start with the first of three examples of community engagement to substantiate this assertion, measured partly in terms of the show's capacity to engage Pacific Islander community members, touch venue staff and visitors and participants such as lenders, scholars, and critics with the warmth, humanity, scholarship and sheer beauty of the end results of our endeavours: the Talking Tapa, Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland exhibition.

-

The first refers to one of only two installations in the exhibition - the mortuary rites presentation of two Queensland Samoan families who used Tongan tapa or ngatu for their mourning rituals and whose separate stories are melded into one installation for the purposes of the show. Savali Harvey is a very busy person. She wanted to contribute but was too tied up in other business. Her late uncle Tapuala however, kept nagging her, niggling away until she wrote the story of her father's passing, for her aiga (extended family), for the show, and lent the symbolic Tongan ngatu which covered his coffin. Orini Barnett was found through the Pacific Islander networks to still have the Tongan ngatu used for her uncle's last rites. In this case the large 5 x 5 metre ngatu had been given specifically to her uncle in preparation for his death. It was spread on the floor under his coffin on his last night before burial and for his whole extended family to sleep on and keep him company on that last night. Together this funeral installation emanates peace, gentle elegance and helps to ground the whole exhibition. Its grace is essential to the show's success I think.

-

This floor ngatu had a strong and varied life before its use for Uncle Lina's mortuary rites.. It was used to decorate the meeting hall for the Logan Samoan Advisory Committee , 21st Birthday parties, and since continues its life of journeying and connecting as part of the travelling Talking Tapa show. It will continue to journey after this show is over, as it gets lent again and gifted on.

-

The other travelling ngatu in the show, listed as the graduation ngatu, relates to conferences such as the AAAPS conference in Melbourne where I presented this paper. Dr. Max Quanchi was given it in thanks for speaking at a graduation ceremony on Eau Island, Tonga. It hung at the Carseldine campus of Queensland University of Technology for less than a year before being lent for this exhibition. After this show it will go to another Pacific nation via the next Pacific History Association Conference in Goroka, PNG. Such examples are becoming more common now and regularly include Australia as part of the provenance and travelling life of a tapa, particularly Tongan tapa or ngatu.

Figure 2. Fiji – Detail of upper skirt of male wedding set worn by Lote Tuqiri, 2005. Courtesy of Jiowana Dau Miles. Source: Catalogue, Talking Tapa: Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland, p. 9.

Figure 2. Fiji – Detail of upper skirt of male wedding set worn by Lote Tuqiri, 2005. Courtesy of Jiowana Dau Miles. Source: Catalogue, Talking Tapa: Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland, p. 9.

| |

Figure 3. I Sulu ni Vakamau: woman's wedding set. Source: Catalogue, Talking Tapa: Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland, p. 13.

Figure 3. I Sulu ni Vakamau: woman's wedding set. Source: Catalogue, Talking Tapa: Pasifika Bark Cloth in Queensland, p. 13.

|

-

The second group of examples of community engagement for Talking Tapa is a counterbalance of sorts to the peace of the funeral installation since it celebrates a more joyful rite of passage: marriage. The wedding outfits, i sulu ni vakamau, for two brides, flower girl and groom centres partly on the industry of Jiowana Dau Delai Miles, a Fijian who came to Brisbane for a holiday, married here and has since spent her time between Fiji and Brisbane. She was a continuing presence for this project. As a Fijian cultural worker she acts principally as a wedding consultant, dressing bridal parties in tapa and decorating their wedding receptions in Fijian style both in Brisbane and Fiji. Jiowana was passionate about Talking Tapa and central to its success. For over a year, perhaps fourteen months, I tried to acquire the wedding outfits of the Tuicolo family in Brisbane. The father is a well known community leader and they live in the same suburb as myself. Despite having met various members of the family and having long discussions about keeping these uniquely commissioned outfits safe, I met a dead end. Then one day the Tuicolos heard that Jiowana worked on the show too. Instantly they offered everything to do with the bridal parties' outfits and the bride's mother wrote the story you can read on page 18 of the exhibition catalogue. The need for such familiarity, of extended family, and knowing Jiowana with her sense of cultural integrity, was essential to their positive participation. This was why this fine example of a female commissioned wedding set for bride and flower girl could grace the exhibition, along with a smoked tapa male wedding set also made possible through Jiowana's extensive networking.

-

Lote Tuqiri, the eminent sportsman, was proud to be married in Brisbane in Fijian traditional style in his hired i sulu ni vakamau. We tried to locate it through his family but they could not remember what had happened to it; we asked Lote through his manager, another dead end. Then, wammo, Jiowana had it together with photos, she had taken at his wedding. Getting a prominent Australian Fijian sportsman onside would have been helpful particularly for those venues which would have appreciated the populist appeal that Lote's engagement would have provided for Fijians and other Australians alike. But therein also lay a common challenge I have found working with Indigenous groups: namely issues of understanding notions of copyright, and loans to exhibitions in the public interest versus commercial interests. We could use his wedding outfit because it was actually on hire, and the photos taken by other Fijians at his wedding. Though his family was interested because they knew several Fijians involved in the exhibition, he and his manager were not, perhaps because of the possible confusion of only being able to see the exhibition in a commercial, palangi style context.

-

Promoting understanding of the value, standards and contexts embedded in shows like Talking Tapa was often difficult and time-consuming because most Pacific Island community members had nothing to compare it to, no prior experience to relate it to.

-

The third example of community engagement is of a different nature. It is about getting the facts, getting history right. All the available literature I had read on the tiputi or tipota, the cloak or poncho like tapa upper over garment suggested that the tipota became a popular garment or was even invented in Hawai'i during the post-contact era, for those converting to Christianity to improve their modesty and render them more acceptable to the colonizers. After hours and hours of talking with the exhibition's Samoan consultants, Koleta Galumalemana and Filipina Petelo, Koleta remembered why, from a Samoan perspective, this could not be so. The thirteenth century legend of the Goddess Nafanua tells of how she disguised herself as a man by wearing a tipota. Her followers never knew she was a woman until they went to war to capture the lands of Amoa i Sasae and Amoa i Sisifo Pule on Savai'i. During the battle Nafanua's tipota blew up and revealed her breasts. Her secret was out. To this day there is a place on Savai'i called Malae ole Ma or Court of Embarrassment. This story is retold on page 36 of the Talking Tapa catalogue. Koleta also expanded the list of known Samoan siapo (tapa) design elements with her rigorous oral research, not recorded elsewhere to my knowledge.

-

While such finds are not earth shattering they do point to how misinformation can develop and become entrenched not only for the consumers of Western knowledge forms but for the Indigenous peoples from where they arise. Koleta stuck to the task of serious information gathering partly because she was being paid. It is a continual oversight today when government funding bodies, museums, galleries and the like somehow continue to think that those from our multicultural communities should offer their services free of charge, or for little charge purely for the altruistic motive of getting their own cultures 'out there'.

-

The Paperskin exhibition at Queensland Art Gallery was an example of the lack of the sorts of community engagement described above. Factual and contextual information was missing. For example, most of the Fijian works in this show were incorrectly attributed as plain masi. Masi has become the generic word for beaten bark cloth in Fiji though traditionally it would rarely have been used by itself as even the undecorated white starting point of masi is called masi vulavula. As all this exhibition's examples of Fijian bark cloth were painted, stencilled and decorated with vegetable dyes and paint their names should have reflected this. Masi is not only named for its decoration and the manner of the design work. So, for example, masi stencilled with three-sided border patterns is called masi solofu; brown smoked tapa is masi kuvui, yellow turmeric dyed tapa is masi rerega, etc. Its various names are also designated by the uses to which it is put. So, for example the three-sided border designed upper skirt of a wedding outfit has its name as do all the elements of the set. A masi kesa used as the top most layer of a ceremonial mound is called i dela ni dabedabe in the Lau Islands. Of the works in the Paperskin show only one caption began to attribute the masi correctly: masi bola. Masi kesa, meaning stencil painted patterned tapa is the basic starting point for correctly attributing this multi-layered artform in Fiji.

-

Again such reappraisals may seem minor but it does beg the question of responsibility. Does a state or national art gallery or museum, for example, have a responsibility to present objects in their collections in the context of that object's provenance and heritage? Do they have the responsibility to respect and honour and in so doing ensure that an object displayed is attributed as accurately as possible? My biggest concern here is that as Pacific Islander numbers increase and Australian-born people of Pacific Islander heritage lose more and more knowledge of their cultures of origin, that the apparent disregard for accurate research information now may compound such diminishing cultural knowledge rather than help to maintain it, as is the job of major collecting institutions.

-

Some Pacific Islander people who worked on this exhibition at first wondered about the level of information which was sought, but those most interested did get it and once they opened up there was a flood, sometimes too late alas, but still thankfully evident. So, having first wondered why a palangi/whitefella like me would be so interested, they remembered legends, history, facts and words related to tapa but which were not encoded on our world wide web or anywhere else outside the families, the gatherings and the rituals of women and men who make and use tapa.

|