FIONA DAVIES

-

What I examine briefly in this paper are a range of artistic and curatorial approaches taken in four

| |

contemporary exhibitions which focused on the use of the material of bark cloth or tapa. These exhibitions were Talking Tapa, Paperskin, and two individual works within larger group exhibitions: Teitei Vou (A New Garden) and As Venereal Theists Rest/The Natives are Restless. These different approaches impact on the ways the works are presented, read, and by whom and the ways these works engage with contemporary diasporic Pacific communities. My context for this examination is to focus on the interplay between looking at tapa or barkcloth as a work of 'art' and looking at those objects instead when they carry or express a way of being or a model of action (as in Bouriand's conception of relational art.[1]

Figure 1. Fiona Davies. Photographer, Alex Wisser.

|

-

The first exhibition under consideration is Paperskin: Barkcloth across the Pacific (see Figure 2). This was a

joint exhibition between Te Papa Tongarewa, Queensland Art Gallery and the Queensland Museum. I saw it when it was exhibited in Queensland in 2009 at the Queensland Art Gallery. In this exhibition, barkcloth from the collections of those three public collections and from a private collector (Harold Gallasch of South Australia) were pulled together to cover a range of Pacific countries. The ages of the tapa ranged from the eighteenth century through to 2006. The creators ranged from 'unattributed', which could be reasonably presumed to mean collaborative groups of women (or men) to those made and attributed to individual artists. The gifting history prior to the acquisition by the collection was not noted or referred to in the labelling, but only the gifting to the institution, as appropriate.

Figure 2. Catalogue of Paperskin: Barkcloth across the Pacific.[2]

| |

|

-

In the catalogue "Preface", Nicholas Thomas positions the exhibition as an art exhibition: 'No major art exhibition has been dedicated to barkcloth until now.'[3] He tempers this by saying

At the same time barkcloths are not solely, or not exactly, works of art: the terminological debate is ultimately unproductive, but it is it important to remember that these were not made for aesthetic appreciation in a narrow sense but rather to constitute sanctity, to define a ceremony, to wrap around a body, to bear knowledge or to effect a gift. These art forms were embedded in the lives of Pacific Islanders, and in many ways, they still are.[4]

-

Yet this exhibition was firmly located as being received by a contemporary art audience, and the objects were catalogued and confined by museuological practice and concerns. The objects were physically separated from the viewer for the safety of both and presented in ways that reflected the ways art objects are usually presented within western institutions: often smallish pieces of tapa were hung on the wall and there were attempts to make them hang flat. The labelling reflected the museum/gallery's concern with provenance and the process of acquisition.

-

The three dimensional masks on display from Baining, East New Britain are usually used in a purely ephemeral manner, made for a single ceremony and then discarded. The traces of their use were seen on some of the masks in the exhibition: bits were burnt off and they were stained by the sweat of the performer. Videos were used in the exhibition to illustrate the use of these masks in ceremonies. The Catalogue from Paperskin is online and contains images of all of the tapa in the exhibition together with the labelling illustrating the points I have made above.

-

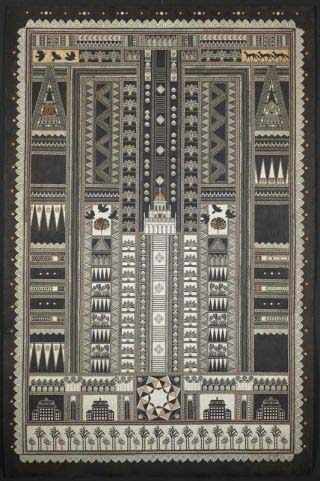

The next exhibition I consider is a tapa displayed alongside other objects as part of the major contemporary art triennial – the Asia Pacific Triennial of 2009/2010 in Brisbane, at the Gallery of Modern Art and the

| |

Queensland Art Gallery. Again the context envisaged was its reception by a contemporary art audience. As the work had already been purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery it was framed by that gallery's practices and concerns for acquisition. This installation was a collaborative work by a New Zealand artist Robin White, and two Fijian artists Leba Toki and Bale Jione. It was entitled Teitei Vou (A New Garden) and made in 2009 from barkcloth, natural dyes, woven pandanus, commercial wool, woven barkcloth, and sari fabric mats (see Figure 3). The references were similarly multi layered. All of the artists are of the Baha'i faith and the symbols, iconography and meanings of that faith have informed the work. The physical orientation of the work referenced the form of the Fijian wedding bower. The intention of the work did not appear to be well served by its hang within the exhibition. The western white cube installation can accommodate many objects and can operate on many levels but the location of this tapa within that white cube limited the meanings that could be easily imparted. The allusion to the bridal bower was not served by its orientation since the main approaches to the work were from the sides, with the front, direct view limited by space. The work looked a little dull in the subdued lighting.

Figure 3. Robin White, Leba Toki and Bale Jione, Teitei Vou, 2009.[5] Courtesy Gallery of Modern Art Queensland

|

-

Robin White, the New Zealand artist has previously described her artistic process as exploring the interface between cultures and arriving at a visual metaphor for the concept of unity in diversity, to sit in the balance between what is familiar and traditional and what is unexpected and new.[6] An article in the Jakarta Post on 13 December 2009 quotes from the collaborative team: ' We're so happy to be here among well educated artists' Bale Jione said of the experience. 'We are not well educated and we are happy because Robin White has helped us to use our art to make our lives better I have seven children and for a very long time I have struggled.'[7] Contrast this with a statement by Robin White in an article in Art New Zealand,

'I don't' feel like a colonist. My family has been here for many generations – my father's lineage goes right back to the Maori and my mother's goes back to the first settlers in the Bay of Plenty area. I really do feel that this is my country. I've got no particular interest in any other artist heritage and I don't feel I owe anything to what's happened in Britain, America France or Italy.' [8]

-

The differential treatment of the three artists in the catalogue reinforced the impression that this was an exhibition constructed by a western cultural institution. Of the three artists only White's curriculum vitae was published: so important for western art communities but either unknown or not privileged by non-western art communities.

-

Within the third exhibition I consider, Talking Tapa curated by Joan Winter, a wedding bower and a wedding presentation of Fijian tapa were also included. This exhibition was produced with significant community engagement resulting in highly contextualised works, for instance in conveying the use of tapa in funeral practices, even if the tapa was still framed by the museum/gallery context.

-

Interestingly in the Paperskin catalogue, curator Sean Mallon from Te Papa starts his essay by relating the story of the burial of his Samoan grandfather in a New Zealand cemetery wrapped in a large Tongan ngatu.[9] But the context of this personal story is probably difficult for the viewer to layer onto the objects in the Paperskin exhibition as there were few works in that exhibition which were large enough to wrap around a coffin. The diminished size of most of the tapa, combined with the western-style flat hanging on walls as the primary mode of presentation likely made it difficult for a viewer to make the conceptual leap to imagining one of these 'precious conserved' tapas being used in such an intimate and ephemeral way.

-

By contrast, in the Talking Tapa exhibition this leap could be made easily. The diary of process of a funeral was outlined in the catalogue while the ample physical presentation of large tapa allowed the viewer to imagine its use in the everyday processes of funerals and weddings. Images from this exhibition offer context to the works and bring to mind the engaged curatorial process with extensive community interest and engagement.

-

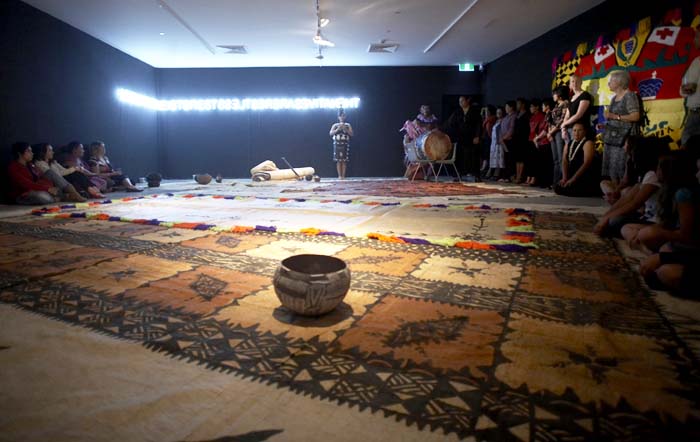

The final exhibition I examine is a work by Newell Harry, As Venereal Theists Rest / The Natives are Restless, made in 2009. This used the mixed media of neon, ceramics, spade and tapa and pandanus textiles made by the Tongan communities of Campbelltown. This was part of Edge of Elsewhere at the Campbelltown Arts Centre and Gallery 4 A in January 2009,[10] an event in the wider Sydney Festival. In this project Harry worked with Tongan and Samoan language groups in South Western Sydney. The work was developed through regular meetings and workshops between the artist and groups working in backyards to create new forms of patterning the tapa with contemporary motifs while the play on words and language in the form of puns and anagrams revealed multiple layers and dualities of meaning.

-

The neon words spelled out 'the natives are restless' and one of its anagrams: 'as venereal theists rest'. Harry described the process of making anagrams as like the cultural agitation brought about by colonial migration. The anagram evoked a process whereby you work with what you are given, mix it up and see what else you can make of it. As Venereal Theists Rest offered an analogy for the infinite number of combinations of circumstances, cultures and beliefs that spin off from colonial migration.

-

A performance by Matingi Tonga celebrated the opening on 15 January 2010 at Campbelltown. The performance within the work is shown in Figures 4, 5 & 6.

Figures 4, 5 & 6. Performance by Matangi Tonga with installation by Newell Harry, Edge of Elsewhere launch, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 15 January 2010. Courtesy the artists. Photo credit: Susannah Wimberley Photography.

In the next few days it was possible once you took your shoes off, to walk on the tapa. As it was summer and most viewers were wearing sandals or thongs a direct sensory physical experience through the soles of their feet of the material was possible.

-

This made me think again about the physicality of tapa. The two characteristics of tapa and how it is used that are most familiar to me are the sheer physicality of the size of tapa sheets and the manner in which they are folded and stacked. I have wanted for quite a few years to curate an exhibition or performance of tapas where a group of women interacted with a stack of their own folded tapas. Each tapa could then be taken out in whatever order chosen, to be discussed, looked at and talked about: for example who was in the collaborative group who made the tapa, was it made as a gift or for ceremonial use, what events had that tapa participated in. Then it might be folded up and put back on the stack. In this way tapa would not exist as decorative backdrop but as an active participant with its own life, history and attributes, combining its value as a work of art with a way of being.

Endnotes

[1] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, Paris: les presses du reel, 2002, (English translation by Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods), p. 13 .

[2] Catalogue of Paperskin: Barkcloth across the Pacific, 2009, online: Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, accessed 16 June 2010.

[3] Nicholas Thomas (2009), 'Preface,' in Paperskin: The Art of Tapa Cloth, Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, pp. 8–9, p. 8, online: http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/WhatsOn/exhibitions/Paperskin/Paperskinexhibition/Pages/Onlinecatalogue.aspx, accessed 16 June 2010.

[4] Thomas, 'Preface,' p. 9.

[5] Source: 'Leba Toki, Bale Jione & Robin White,' Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, online: http://qag.qld.gov.au/exhibitions/past/recently_archived/apt6/artists/robin_white,_bale_jione_-and-_leba_toki, accessed 16 June 2010.

[6] 'Art on Fijian bark cloth reflects unity in diversity,' in Bahá'í World News Service: Baháa'í International Community, 25 November 2000, online, http://news.bahai.org/story/77, accessed 16 June 2010.

[7] Cynthia Webb, 'Learning to experience life as art,' in the Jakarta Post, 13 December 2009, online:

http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2009/12/13/learning-experience-life-art.html, accessed 16 June 2010.

[8] Robin White, 'Art and conservation are synonymous,' in Art New Zealand, no. 7, (Spring 1977), online: http://www.art-newzealand.com/Issues1to40/environrw.htm, accessed 16 June 2010.

[9] Sean Mellon, 'Beyond the paperskin,' in Paperskin: The Art of Tapa Cloth, Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, 2009, pp. 23-31, p. 23, online: http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/SiteCollectionDocuments/Exhibitions/Paperskin.Publication.Essay2.Sean%20Mallon.pdf, accessed 16 June 2010.

[10] Media Kit – Edge of Elsewhere, produced for the Sydney Festival by Campbelltown Arts Centre in partnership with Gallery 4A, Australian Centre for Asian Art & Archaeology and the University of Sydney.

|