|

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific

Issue 50, December 2023 doi: https://doi.org/10.25911/PH5T-2M95 |

|

Aleena Shahzad Department of English, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad hard and full of rancour, clash in the air where suddenly stones clash Bodies like a greedy sea clashing in fury. In solitude bound by love, by hatred. Men rise out of all veins; spiteful they cross cities. As you treat me so, Heaven, I try to understand what was my crime against you by being born, while still, I grasp by the very fact of birth what crime it was. Your unrelenting justice has sufficient cause: Man’s greatest crime is simply to have been born. The beast is born with skin of dappled beauty. No sooner constellation by Nature’s skilful brush, when sheer necessity, unremitting and cruel, teaches it cruelty, a monster in its labyrinth. Then how is it that I, endowed with better instinct, enjoy less liberty? The stream is born, a snake uncoiling in the flowers. This silver serpent scarcely breaks through blossoms but it celebrates their grace with music, flowing with majesty to the open plain. Then how can I whoever greater life enjoy less liberty? Hitting this pitch of grief What law, justice, reason, can deny to man a privilege so sweet, so tall a grace as God gives stream, fish, beast and bird? Miguel Hernández, 'After Love.'

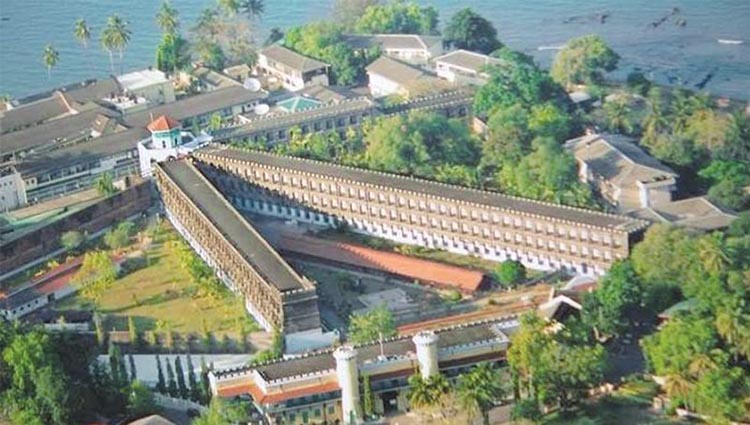

Introduction This prison poem titled 'After Love' written by Miguel Hernández and translated by Michael Smith,[1] explains the oppression and acrimonious feelings that lurk in the hearts of marginalised prisoners. Stripped by opinion and individuality, they are pushed into a spiral of silence, contemplating their existence as a speck of dust in a perturbed ambiance. It is pertinent to delve into the historical backdrop of Nadia Hashimi’s A House Without Windows and Uzma Aslam Khan’s The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, to get familiar with the intricate concerns. Barret Wendell said: 'Literature is a form of travel; it enables us to move about freely among the minds of other races, it gives us the power of traveling also in time.'[2] A House Without Windows and The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, cascade the actual past history of Afghan and Indian prisoners in their own unique ways.[3] In the context of Afghanistan, Human Rights Watch is an international non-profit organisation that compiled the stories of females who were arrested because they left their homes, families and husbands. The Afghan females are also alleged to have committed moral crimes like zina (adultery) and sexuality-related offences.[4] In addition to this, the carnage of war also has had an overwhelming influence on the social fabric of women's lives that makes them socially, economically and emotionally crippled.[5] The work of a Canadian photographer Gabriela Maj, titled Almond Garden: Portraits from the Women's Prisons in Afghanistan, is a critical window to the backdrop of the novel A House Without Windows which was explained by Hashimi in her interview.[6] Maj travelled across Afghanistan to collect a myriad of stories and portraits of female prisoners. Hence, Almond Garden with its pictorial orientation pays homage to those Afghan females who fought with audacity amidst patriarchy. The cellular jail in Andaman Island in The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali is imbued with gruesome episodes of history that enrich its literary and critical aesthetics. Drawing inspiration from Nadya Mujahid's pictorial image in an article titled 'Fiction: Black Waters of History' in DAWN,[7] I contend that the seven arms of the star-shaped prison on Andaman Island continue to hold its prison aesthetics in the sense that it has been dedicated to the Indian nation as a National Memorial.

Figure 1. The Cellular Jail at Andaman Island. Only three of the original seven wings remain and the building is now a national memorial. Source. Nadya Chishty-Mujahid, 'Fiction: Black Waters of History,' DAWN Newspaper, 12 May 2019, accessed 7 Nov. 2022. In the past, Indian prisoners were imprisoned in these cellular jails and were subjected to British colonisation. Cellular jails remind us of the intimidation and sheer atrocities committed by the British regime in the remotest parts of India.[8] Each cell of the prison has its own surreptitious heart-rending story of bestial attitudes. The political prisoners in the jail were the victims of ill-treatment that escalated into a hunger strike. The horrors of prison life included inhumane torture in the form of neck ring shackles, bar fetters, leg iron chains, oil grinding, poor diet, coconut coir rope making, merciless beating and many more.[9] When the Japanese occupied Andaman Island in March 1942, the islanders were brutally tortured. All these actual episodes of history are interwoven in the literary fabric of both novels and my paper aims to spotlight the aesthetics of prison which impacts on the mental outlook of the Afghan and Indian prisoners that makes their body spaces either rejuvenating or negating in their own unique ways. For instance, in the novel A House Without Windows, the female body spaces in the prison provide a rejuvenating experience because the incarcerated women are allowed to discover their breathing existence in the graffiti contours of the prison. In The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, the female Indian prisoners’ body spaces were sabotaged because they were not given proper food and forced to do laborious tasks. The novels Before probing into the rich critical matrix of the present debate, I would like to add a comprehensive literary snapshot of both my selected novels to contextualise the argument of my paper. The debut novel A House Without Windows by Nadia Hashimi revolves around a prison in Kabul named Chil Mehtab where women were imprisoned on the charge of 'crimes of immortality.' Zeba, the main character is suspected of murdering her husband and she was put into prison for this alleged crime. Furthermore, she was also sent to the shrine with the false notion that she is mentally unstable, and she became the victim of the sheer atrocity.[10] It was the belief of the local people that Zeba is bewitched by some supernatural forces, so they considered the shrine as an antidote for her disease. But she did not recover. At that critical point, the prison Chil Mehtab serves as breathing space for her. It shows runaway girls and betrayed mothers, each with a gruesome tale of family honour to tell and prison serves as a haven for them. Zeba was the daughter of a sorcerer named Gulnaz. While in prison she befriended cellmates like Meghan, Latifa and Nafisa. The prison interiors described in the novel are vibrant spaces and equipped with a make-up room, radio, fashion magazines, newspapers and TV, which alleviates the sufferings of the women prisoners and facilitates collective revitalisation. While 'inside' the female prisoners register the pacifying impact of the prison on their bodies in the form of tattoos, and Zeba inscribes her the name on the walls of her prison cell. An English Fiction Award winner, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali (2020) is set on an island in the Andaman Archipelago. The story revolves around Nomi and Zee who are local born. Their father is a convict condemned by the British to prison on the Andaman Islands. Their mother is shipped off with him. When war descends upon this overlooked outpost of the Empire and the Japanese move in, Zee is forced to flee, leaving Nomi and the other islanders to contend with a new malice. Moreover, while the novel encapsulates a plethora of characters, my paper aims to bring into the limelight the female prisoners, their interactions with the starfish jail, and how it impacts on their subjectivity. Most of the female prisoners are nameless and they are recognised only by the wooden block ticket that is hung around their necks. One of the females is prisoner 218-D who wages war with her body. The prisoners are divided into two groups—ordinary and political—and they are imprisoned in different levels of the jail. Andaman Island with its surreal beauty is the locus of the battlefield for the female prisoners who worked in the jail's factory making napkins, uniforms, soaps and matches. It is a battlefield because the women prisoners were barred from their choices and identity. They had to endure corporeal punishment if they become lazy in making soap, matches, and napkins in the factory. They were forced to live and be force-fed when they got sick from the tedious factory work. The superintendent of the jail, Mr. Howard, and his assistant named Aye, monitored the activities of the female prisoners. Another character named Cillian was detained to inflict torture on the female prisoners with the help of a bamboo truncheon. Holistically speaking, the Indian female prisoners and their bodies were subjugated to the prison's internal bestial ambiance. They showed their resilience by reciting poetry and writing letters to their family members. These activities gave them breathing spaces for survival in this place where incarcerated humanity was reduced to a nadir point. More importantly, depriving someone of food is cruel, but forcing them to smell fancy food items and not allowing them to eat them is the height of cruelty. Instead of delicious food, women prisoners were forced to eat live worms, mice droppings mixed with stones and boiled rice. In this way, women prisoners' bodies became 'commonwealth bodies' that were cruelly treated by the British regime. The author (Uzma Aslam Khan) skilfully draws out these atrocities in the literary texture of The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali. Prison aesthetics Given the scope of the essay, my primary argument is to foreground the aesthetics of the prison and the way it affects the mental outlook and the subjectivity of the Afghan and the Indian prisoners in A House Without Windows and The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, respectively. I contend that the internal rich aesthetics of the prison helps Afghan females in their process of rejuvenation from past wounds, but the external contours of the cellular jail in South Andaman Island, while more visually appealing, exudes an ambiance of torture. The females survive by developing a fragile resilience in the form of poetry recitation, writing letters and helping each other in the factory. Drawing upon the notions of Yvonne Jewkes 'prison aesthetics' and Donald Clemmer's 'prisonisation,'[11] I discuss the ways that the Chil Mehtab prison in A House Without Windows and the cellular star-fish Jail in South Andaman Island are enmeshed with a vibrant internal texture that synergises the feelings of the Afghan and Indian female prisoners who are ostracised from mainstream society.[12] Jewkes contends that prison 'is not limited or classified or pigeonholed but it presents internally diverse and fluid spaces' which elevate the aesthetic appeal of external and internal carceral geography which she termed 'prison aesthetics.'[13] My article is a departure from the traditional idea of imprisonment by dismantling the ugly and grotesque outlook of prison spaces into 'contemporary, progressive and humanitarian design.'[14] Moreover, I explain the ways that female prisoners are engaged with their fellow cellmates and prison culture in ways that help them in negotiating their shared pain. In doing so, Clemmer's concept of 'prisonisation' helps me to envisage the crucial aspect that lies at the heart of this critical debate—that is how the female prisoners foster breathing spaces of their own existence by dwelling on their past personal experiences which gives a soothing impact to their mental outlook. Clemmer contends that 'prisonization occurs to all inmates, to varying degrees, immediately upon entering the prison doors.'[15] This means that prisoners develop a connection with other inmates, and they immediately assimilate into prison culture in this process of prisonisation. To spotlight the process of prisonisation, I argue that Jewkes's prison aesthetics, coupled with Michel Foucault's concept of 'heterotopia' help in my textual engagement with both novels. The term 'heterotopia' is central to those who are 'dispossessed, subaltern or oppressed.'[16] Chil Mehtab provides a collective heterotopic space for female prisoners, where they are able to contemplate their situation and share their sufferings in ways that soothe their inner mental anguish. The prison becomes a home for them.[17] Moreover, their physical and mental outlook has been brushed aside on account of the immoral crimes (viewed through patriarchal and chauvinistic lenses) with which they have been charged and subsequently imprisoned in Chil Mehtab. These women prisoners have been removed from the social space and, as seen through Foucault's 'heterotopia of deviance,' the prisons are sites of social abandonment.[18] Nadia Hashimi: A House Without Windows To navigate the rich tapestry of prison aesthetics, textual engagement highlights the concerns of the voiceless people in the prison space of Chil Mehtab in Hashimi's A House Without Windows. I argue that in the colourful tapestry of prison aesthetics, the prison space of Chil Mehtab provides items to help the women prisoners pacify their perturbed states of mind. This relationship is not uni-directional. Rather it is reciprocal in the sense that the female prisoners affix family photographs to the walls by their beds and are absorbed in doing embroidery. This craft activity suggests that they are bringing their culture into the prison space. This essence has been reflected in the novel by Hashimi as: The other woman had hung up pictures, magazine cutouts, or family photos on the rectangular spaces above their heads. Nafisa had cross-stitched a geometric border in red thread for her white blanket. Latifa had set a vase of artificial roses at the foot of her bed.[19]All the female prisoners in the novel, Mezhgan, Latifa, Bibi Shireen, Nafisa and Zeba, have adapted their spaces for their survival.[20] At this point, it is important to synergise the Jewkes and Dominique Moran critical underpinning of prison aesthetics. They contend that 'spaces … produced and reproduced on a daily basis and the agency of inmates making their own spaces, material and imagined' support prison aesthetics.[21] The textual episode cited above gives an example of this theoretical trajectory where the female prisoners are engrossed in the embellishment of their individual or collective prison space. In the text the internal contours of the prison cell are imbued with accessories such as a wooden table, radio, newspapers and beauty magazines as I mentioned earlier. These accessories (especially those associated with the media) are not static. Instead, they are used by the female prisoners with profound interest.[22] This process is termed 'prisonisation' where inmates have synergised with the rich contours of the prison as well as their cellmates.[23] The cell doors and the gates of the prison were painted blue.[24] I argue that the prison mobilises aesthetic and spatial values for these female prisoners.[25] Therefore, such carceral spaces create a balance between punishment and rehabilitation.[26] The television set in the corner of the cell provided Mezghan and Nafisa with the opportunity to watch Turkish soap operas. The prison spaces of Chil Mehtab are 'not limited, classified or pigeonholed but … present internally diverse and fluid spaces,' which elevate the aesthetic appeal of external and internal carceral geography which Jewkes has termed 'prison aesthetics.'[27] Given the scope of this essay, my argument is premised on the opinion that the prison is not only providing a physical aesthetic space, but female prisoners are engaged in activities that amplify the aesthetic appeal of Chil Mehtab and foster 'prisonisation.' Without the engagement of the prisoners with Chil Mehtab's aesthetic space, the prison would remain static. I argue that the prison space of Chil Mehtab is alive because of the creative energy and eager involvement of the female prisoners. The prison space is contested and personalised by every female prisoner with different intensities.[28] For instance, the female prisoners are busy with different activities in the makeup parlour—a small room with a pleasant and aesthetic ambience. Nadia Hashimi has constructed it in the novel as: Gaping drawers revealed round and flat hairbrushes, tins full of bobby pins, and tubes of lipstick. A can of hair spray sat atop the counter. One freshly coiffed prisoner sat in the chair, twisting her neck and torso to get a look at the back of her head. Two other women, with rust-coloured fingertips stained with henna, stood around her.[29]My paper gives voice to the painful stories of love, sex and violence that are shared by the female prisoners in Chil Mehtab. The prison space enables the protagonist, Zeba, to solve the problems of the female prisoners by exercising the craft of magic which she has learned from her mother, Gulnaz. My intention is not to delve into the notion of necromancy. Instead, my task is to highlight the way the prison space serves as a troupe of prisonisation where the problems of the females (with which they had grappled alone for so many years) were solved by their intermingling. Nevertheless, it is crucial to mention that the use of magic has not been negatively charged by Hashimi. Rather Chil Mehtab is the canvas on which Zeba crafts this skill to help the incarcerated females who are not acknowledged by society. By fixing their familial problems, the space of Chil Mehtab has a balming effect. One example is Mezhgan. She was in Chil Mehtab because she wanted to marry a man of whom her family disapproved. She had not followed the tradition of patriarchy where the male member of the family solely decides marital affairs. She consulted Zeba to use her magic tricks and fix her problem by saying: 'Please, Zeba. I swear to you he's my beloved and I am his. We are destined to be together. We need only someone to unlock our fates.'[30] Later on, her problem is solved; she is accepted by her family who arranged a festive marriage ceremony for Mezhgan and the person she wanted to marry. In the novel, Chil Mehtab simmered with anticipation at this activity and chocolates were distributed from cell to cell.[31] Last, but not least, Zeba was punished by the prison authorities. Because a spurious allegation that she was possessed by evil spirits was lodged against her, she was sent to the shrine and fed with bread, black pepper and water for forty days.[32] In that precarious situation, Chil Mehtab served as a space where Zeba was in the process of prisonisation, in which the jelling of the female prisoners with prison culture bound them in a 'therapeutic' community.[33] I now turn my attention to the second novel under discussion. Uzma Aslam Khan: The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali Given the critical and aesthetic scope of my essay, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali by Uzma Aslam Khan has a unique idiosyncratic appeal in its prison aesthetics which cannot be overlooked. The mesmerising ambience of Andaman Island with its surrealist beauty captures the outer rich contours of the cellular jail that looked like a starfish.[34] I argue that Andaman Island amplifies the aesthetics of the starfish jail. In the novel, Khan manifests these aesthetics as follows: The islands were breathing. The whole universe seemed to sing. The sea was so many greens and blues, all glassy and glittering. The surf rolled sweetly along the white beaches, though she had never known a beach to be white, a surf to be sweet.[35]On Andaman Island, there was The Jail. 'Shaped like a red starfish, the colour of the wound, its seven arms were severed by tall, tall trees.'[36] I contend that the linguistic orientation of the word 'starfish jail [with] its seven arms' is imbued aesthetically with a pictorial manifestation so that readers can better capture and contemplate the external and internal contours of the jail. Unlike the prison aesthetics of Hashimi's novel which were revitalising in terms of inner contours, in Khan's novel, the red starfish jail is not revitalising in terms of inner contours, but its outer contours are aesthetically appealing because of its location. Moreover, the process of 'prisonisation' is more challenging in the ambience of the starfish jail as compared to Hashimi's novel where the prison provided substantial spaces in which the women could grow. My focus in this section is to spotlight the prison contours which are not rejuvenating and to highlight the ways in which the female prisoners struggled to achieve prisonisation in the form of different items like clay, songs and the writing of letters. The ship S.S. Noor was used to carry prisoners to the starfish jail—a space that comprises 693 cells. Unlike Hashimi's novel, where the cell doors and gates were painted with a cheerful blue,[37] the jail in Khan's novel was embellished with iron belts, shackles and high walls. In the novel, Khan constructs this ambience: 'At the entrance to the jail, the high wall [was] garlanded with manacles, shackles, iron belts and implements of torture impossible to name.'[38] In the red starfish jail, the female prisoners worked in the Factory where they performed many tasks like sewing napkins, uniforms and making soap and match sticks for the Britishers. In addition to this, there was a strict digital surveillance system that was used to monitor the activities of the prisoners. One of the windows was screened by a spider web which caught pink light that flickered if she turned her head just so. The jail has three levels and 693 cells along seven corridors or limbs, to those who see the jail as the starfish—radiating from the central watchtower.Inside the watchtower a single sentry was able to observe each inmate like a god—reminiscent of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon, as used by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison.[39] Following Jewkes, I contend that the starfish jail provides diverse spaces for the female prisoners, but those spaces are not rejuvenating sites. Instead, the Andaman Jail promotes torture and immobilises the body spaces of female prisoners. The female prisoner with a wooden tag, 218-D, has to sleep on a wooden bed that cuts into her flesh. She was chained with neck ring shackles because her wooden tag 'D' stands for dangerous. She was forced to eat 'thick, hard roti' for breakfast and other prisoners in the Female factory were given a mixture of stones and mice droppings in their bowls. Prisoner 218-D used to hear the male prisoners, who were working in the mill extracting mustard oil from mustard seeds, screaming. Clouds of melancholy and alienation coupled with a bestial ambience made her life miserable. Khan portrayed it this way: 'Her isolation was turning into a strange creature, empty of vigour, like the stones she has to eat. The opposite of peace is not war. The opposite of peace is inertia.'[40] Amidst the precarious prison environment of the starfish jail, the female prisoners, especially Prisoner 218-D, struggled to cultivate 'prisonisation.' To achieve this, she embarked on a journey of rediscovering her emotions through her association with various things like clay, songs, nature, breeze, poetry and the word rimjhim. This enforces the idea that the prisoners don't come as 'blank slates,' they develop nostalgia and intimacy for past associations. For instance, in the cell of prisoner 218-D, the ceiling leaked raindrops and those raindrops or rimjhim reminded her of her father because he had an affinity with rain. Khan said: 'She has dug deep into the pit of her hollow stomach to find it, the world she would give if brought paper and pencil again. Rimjhim. A word that means exactly what it is and nothing more, or less.'[41] The word rimjhim, resonates with the critical concept of 'trans-carceral space' voiced by Anke Allspach where the prisoners get affective emotional patterns from their outside environment in the midst of imprisonment.[42] Second, for prisoner 218-D on her way to the starfish jail, the serene atmosphere of the island soothed the pain of her impending imprisonment. I argue that not only the fractured ambiance of the jail helped her to navigate her past associations, but the outer contours of Andaman Island prepared her for the 'prisonisation' that was to occur in the vicinity of the jail. 'She tries to listen to the sea. She tries to remember colours, sunlight, and breezes that tease the crops of open fields. This effort to remember and to forget comes like the waves she cannot hear but can feel, they are there, under her chains.'[43] Third, when she was chained, she could hear the voice of her dead father reciting the lyrics of the poets Bismail, Majaz and Akhter Shirani which gave her hope that she would survive.[44] Fourth, she wanted to eat clay or soil and was contemplating whether it would alleviate her suffering from the death sentence. She remembered the past when her mother used to eat clay for an easy childbirth delivery.[45] In the starfish jail, the prisoners went on a hunger strike because they wanted congenial treatment as well as 'newspapers, light in the cell, better food, warm baths, and no more rough handling.'[46] To me, this clearly illustrates that female prisoner 218-D assimilated into the prison culture—a process termed 'adaptive endurance' by Gresham Skyes.[47] This process helps with the process of 'prisonisation' specifically at an individual level. Prisoner 218-D tolerated the different shades of excruciating physical and mental torture, which Skyes has termed 'pains of imprisonment,'[48] at the hands of the strict institutional enforcers, Mr. Howard and Cillian. I argue that in this novel, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, the intensity of prisonisation is focused on an individual level compared to the collective level in Hashimi's A House Without Windows where fervent collective enthusiasm for prisonisation is demonstrated emphatically. Discussion and analysis Analysing the speciality of female Afghan and Indian prisoners in A House Without Windows and The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali is also the endeavour of my paper because the experiences of the females are profoundly synergised with their respective prisons. Following Elizabeth Grosz, I contend that the prison spaces of Chil Mehtab and the Starfish Jail register on female bodies in the form of either rejuvenation or repulsion because the 'body is a crucial term, a site of contestation, in a series of economic, sexual, political struggles.'[49] In addition, the spatial aesthetics of the prisons affect the subjectivity of female prisoners in different ways.[50] Drawing from Charles W. Mills's notion of a 'commonwealth body,' I also argue that the bodies of the female prisoners in the starfish jail are not in a state of vitality. Their bodily spaces are ruptured and sabotaged by the sheer atrocity of the British regime and their bodies become the locus of terror, silence, experimentation and torture.[51] This is unlike the situation of Afghan prisoners in Chil Mehtab in Hashimi's novel where the females were encouraged to discover their true identity in the graffiti contours of the prison and every facility was provided to them. They could go to a make-up parlour within the prison, and they could watch television. Unlike female prisoners who are working hard in factories making matches, napkins and soap under strict surveillance in Khan’s novel, the Afghan female prisoners in Hashimi’s novel are not doing any laborious tasks—rather they are rejuvenating themselves. Following the critical underpinning of the 'commonwealth body,' Mills argues that 'relations of power are relations that obtain between bodies, and we need to recognize both how power constructs these bodies and how bodies are shaped nonetheless continue to assert their corporeality.'[52] The textual engagement with both novels provides a critical voice to these trajectories relating to bodies and power. My essay contends that the prison space of Chil Mehtab in A House Without Windows has a rejuvenating impact on the body of the female prisoners in a sense that after a session of tattooing had been conducted in the makeup parlour, the name Zeba had been 'written on a dozen body parts.'[53] I corroborate this idea with Allspach's 'transcarceral space' that suggests that tattoos serve as rejuvenating markers for female prisoners beyond the walls of confinement.[54] Those weak imprisoned females whose roles are circumscribed within the four walls of the jail considered that the four-letter name, Zeba, which they have inscribed on their skin, arms and backs, to be a talisman in itself because of the overwhelming process of prisonisation.[55] To register the name of Zeba on their arms in the form of tattoos in the prison space of Chil Mehtab allows the women prisoners to imprint profound therapeutic experiences in their minds. As Grosz explains this phenomenon in this way our body is linked to how we perceive space and time, and it becomes a bodily representation of our understanding.[56] Through bodies, the women are making their minds and the space of Chil Mehtab more rejuvenating by indulging in prison tattooing. Nadia Hashimi has reflected this in the novel: Time passes differently through a woman's body. We are all haunted by all the hours of yesterday and teased by a few moments of tomorrow. That is how we live torn between what has already happened and what is yet to come.[57]At this critical vantage point, the role of Zeba as a prisoner has been transformed and she became known as the 'Queen of Chil Mehtab.' The prison space has been reshaped because Zeba has solved the gruesome problems of most prisoners and her status has been raised to that of a mystic woman.[58] Initially for Zeba, 'prison with its beauty salon and televisions and crayon scribbled walls, was a dungeon’[59] but, later on, she adapted herself and the space of Chil Mehtab occupied a breathing presence for her.[60] Indeed Chil Mehtab became a fully 'lived space' for the women prisoners.[61] However, in Khan's novel, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, the spaces and the female bodies are reduced to utter subjugation in the starfish jail. In this context, I contend that the prison space was not breathing with rejuvenation for the women, rather it further sabotaged the female bodies in a repulsive manner. I use the following example to elucidate. Prisoner 218-D's legs were swollen and there were sores all over her body because of the intense pain of the ring neck shackles and the wooden bed.[62] She was taken to the saltwater tank for bathing and the saltwater left 'white shadows on her skin.'[63] Unlike Hashimi's novel, this novel has less prisonisation at a collective level. This is reflected in the textual episode where other females laughed at Prisoner 218-D when she tried to cover herself from the saltwater scars.[64] Another example of brutality, this time from the prison authorities, happened when Mr. Howard learned that Prisoner 218-D had wasted a spool of thread in the factory and had not sewn anything. She was deprived of fresh water for the next forty-eight hours.[65] Her head was shorn every week which amplified her suffering.[66] Cillian, a jailer, used to inflict physical and mental torture on Prisoner 218-D with his recurrent chant 'Punish her now, Jamadar! Do not reserve for the morrow what can be dealt with today!'[67] Cillian said: 'The flowers she embroidered looked like rats had eaten them.'[68] Initially, she was detained on the loom which ended in a fiasco and she was subsequently shifted to the grinding stone area where she was required to wash clothes in the blazing heat of the sun.[69] I link this brutality with Grosz's contention that the 'body is a pliable entity whose determinate form is provided not simply by biology but through the interaction of modes of the psychical and physical inscription.'[70] With this theoretical trajectory, I contend that in the starfish jail the bodies of the women prisoners became the location of profound self-annihilation because of bitter acrimonious feelings which were given manifestation in the form of violence. Prisoner 218-D lost her subjectivity and autonomous body. Khan put it this way: 'Her body belonged to someone else. And she burned inside.'[71] Her body was reduced to the 'commonwealth body,' which came into being 'by the wills and agreement of men.'[72] Mills asserts that there are two kinds of bodies; one is called a natural body which is the work of nature. The other one is called a commonwealth body, where bodies are the site where patriarchal hegemony is exercised.[73] In a similar vein, Grosz argues that the 'female body is in a struggle with the patriarchy because it restricts their [women's] mobility and social space.'[74] This is demonstrated in the novel when prisoner 218-D became ill and was maltreated in the hospital. When Prisoner 218-D was hospitalised, Mr. Howard, who was the caretaker of the prisoners, said to her: 'It means your body is feeding on muscle, even the muscles of your heart. It means your vital organs are under attack. You can stop that. Here, smell this. He brought to the prisoner's nose a plate of chicken and gravy.'[75] At the heart of this debate, is a concern about food. Food that was provided for the women to smell, but that was invisible because it didn't nourish the bodies of female prisoners. In the hospital, Prisoner 281-D was force-fed fluids including milk administered via a rubber tube that was inserted into her stomach. This forced-fed spectre diet kept the prisoners alive.[76] I will use the term 'spectre food' because the diet that the prisoners were forced to eat presents us with feelings of horror and terror and shows the height of atrocity and sadist attitudes of the authorities of the starfish jail. Food is meant to give nourishment and vitality to the body, but in Khan's text, it is reduced to invisibility and horror with respect to the women prisoners. Hence, the natural bodies of the female prisoners succumbed to the poor diet they were fed and became transformed into commonwealth bodies. Conclusion In this paper I have illuminated the prison aesthetics of the novels A House Without Windows and The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali. Although prison literature is ubiquitous in the arena of South Asia and its palpable existence can be seen in the social reality of Pakistan as well as other places, both novels quintessentially capture the prison aesthetics. Both novels demonstrate how the unique contours of the two prisons affect the subjectivity of the female prisoners in the form of prisonisation that helps them to pacify their suffering at both individual and collective levels. Without literary and critical endeavour, we become subalterns. 'We live in the time of monsters,' stated Jeffery Jerome Cohen and those metaphorical monsters emerge as a result of race, colour, political, cultural, ideological and sexual differences.[77] Hence, these novels along with their trajectories raise the critical consciousness of society. The process of prisonisation helps the female prisoners of Chil Mehtab and the starfish jail to soothe their physical and mental suffering. In doing so, past emotive connections with different objects like clay, poetry, songs, nature, the breeze, family photographs, Turkish soap operas, newspapers and the radio help the women prisoners to breathe and soak up the rejuvenation space provided. The female prisoners in both novels 'perceive and receive information from the world through their bodies.'[78] Precisely speaking, as Salman Akhter explains, 'We are surrounded by things. We are involved with them, indebted to them. We speak to things and things speak to us.'[79] Notes [1] Miguel Herna?ndez, The Prison Poems, trans Michael Smith, West Lafayette IN: Parlor Press, 2008, pp. xix–xxiii. [2] William Henry Hudson, An Introduction to the Study of Literature, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012, p. 41. [3] Nadia Hashmi, A House Without Windows, New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2017; Uzma Aslam Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, Lahore: ILQA Publication, 2020. [4] David E. Nelson, Afghanistan, Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press, 2013, p. 179. [5] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 141. [6] Sasha-Ann Midi, Interview with Nadia Hashimi, YouTube, 15 Sep. 2016, online:, accessed 15 Oct. 2023. [7] Nadya Chishty-Mujahid, 'Fiction: Black Waters of History,' DAWN Newspaper, 12 May 2019, online:, accessed 7 November 2022. [8] R.V.R. Murthy, 'Cellular jail: A century of sacrifices,' The Indian Journal of Political Science 67, no. 4 (2006): 879–88, specifically at p. 885. [9] Murthy, 'Cellular jail,' p. 881. [10] A shrine is a place built over the grave of a revered religious figure, often a Sufi saint or dervish. See Nashima Bari, 'Afghan women, pilgrimages and their devoted beliefs,' The Kaarma Press News Agency, 18 March 2023. Online:, accessed 15 October 2023. [11] Yvonne Jewkes, 'On carceral space and agency,' in Carceral Spaces: Mobility and Agency in Imprisonment and Migrant Detention, ed. Dominique Moran, Nick Gill and Deirdre Conlon, 127–32, Farnham: Ashgate, 2013; Donald Clemmer, The Prison Community, New York, NY: Rinehart & Winston, 1961. [12] Jewkes, 'On carceral space and agency'; Clemmer, The Prison Community. [13] Jewkes, 'On carceral space and agency.' [14] Dominique Moran and Yvonne Jewkes, 'Linking the carceral and the punitive state: A review of research on prison architecture, design, technology and the lived experience of carceral space,' Annales de géographie 2, no 3 (2015): 163–84, doi: 10.3917/ag.702.0163. [15] Mary Bosworth, Encyclopedia of Prisons & Correctional Facilities, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005, p. 138, doi: 10.4135/9781412952514. [16] Katharine Eleanor Lassiter, Recognizing Other Subjects: Feminist Pastoral Theology and the Challenge of Identity, Eugene Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2015, p. 163. [17] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 81. [18] David Murakami Wood, Beyond the Panopticon? Foucault and Surveillance Studies, London: Routledge, 2016, p. 133. [19] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 156. [20] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 155. [21] Moran and Jewkes, ‘Linking the carceral and the punitive state,’ p. 138. [22] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 200. [23] Clemmer, The Prison Community. [24] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 75. [25] Moran and Jewkes, ‘Linking the carceral and the punitive state,’ p. 138. [26] Elaine Fishwick and Michael Wearing, '"Unruly mobilities" in the tracking of young offenders and criminality: Understanding diversionary programs as carceral space,' in Carceral Mobilities: Interrogating Movement in Incarceration, ed. Jennifer Turner and Kimberley Peters, 44–56, London: Routledge, 2017, specifically at p. 46. [27] Jewkes, 'On carceral space and agency,' pp. 127–32. [28] Moran and Jewkes, ‘Linking the carceral and the punitive,' p. 165. [29] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 76. [30] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 156. [31] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 159. [32] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 256. [33] Wilbert M. Gesler, Healing Places, Lanham Md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, p. 30. [34] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 4. 35 Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 6. [36] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 5. [37] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 75. [38] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 20. [39] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, pp. 29 and 81; see also Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. from French by Alan Sheridan, London: Penguin Books, 1978. [40] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 107. [41] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 125. [42] Anke Allspach, Transcarceral Space: Dealing with the Challenges of Imprisonment in America, New York, NY: Routledge, 2019. [43] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 24. [44] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 23. [45] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 22. [46] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 108 [47] Gresham M. Skyes, Criminology, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College, 1992, p. 129. [48] Skyes, Criminology, p. 126. [49] Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 19. [50] Richard Hornby, ‘Spatial aesthetics,’ The Hudson Review 61(4) (2009): 780–86, specifically at p. 780. [51] Charles W. Mills, 'Body politic, bodies impolitic,' Social Research 78, no. 2 (2011): 583–606, specifically at p. 589, doi: 10.1353/sor.2011.0041. [52] Mills, 'Body politic, bodies impolitic,’ p. 588. [53] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 337. [54] Allspach, Transcarceral Space: Dealing with the Challenges of Imprisonment in America. [55] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 342. [56] Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 87. [57] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 138. [58] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 342. [59] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 204. [60] Hashimi, A House Without Windows, p. 398. [61] Edward Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory, London: Verso, 1989, p. 262. [62] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 83. [63] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 106. [64] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 106. [65] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 124. [66] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 106. [67] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 128. [68] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 130. [69] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 130. [70] Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 187. [71] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 130. [72] Mills, 'Body politic, bodies impolitic,’ p. 589. [73] Mills, 'Body politic, bodies impolitic,’ p. 589. [74] Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 19. [75] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 142. [76] Khan, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, p. 117. [77] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Monster Theory: Reading Culture, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1996, p. ix, doi: 10.5749/j.ctttsq4d. [78] Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 10. [79] Salman Akhter, Objects of Our Desire: Exploring Our Intimate Connections with the Things Around Us, New York, NY: Harmony Books, 2005, p. 26. |

|