|

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific

Issue 50, December 2023 doi: https://doi.org/10.25911/8M1H-2D56 |

|

Interventions of Pa. Ranjith and Mari Selvaraj Swarnavel Eswaran This essay engages the Tamil movies Madras (2014)[1] and Sarpatta Parambarai (Sarpatta Clan, 2021),[2] directed by Pa. Ranjith and Pariyerum Perumal (Horse-mounting Deity, 2018)[3] and Karnan (2021),[4] directed by Mari Selvaraj to argue for their uniqueness in highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of Dalit masculinity. Ranjith's Madras and Sarpatta Parambarai are remarkable for their profound engagement with the existential angst of their protagonists. They are targeted because of their caste, family and community. Therefore, Ranjith uses masculinity as a lens through which to analyse it against the spirited but well-meaning femininity around his protagonists. Further, he uses it to explore its resilience against the systemic evil of caste and its hegemony. Mari Selvaraj, a filmmaker from the deep south of India, is unique because of his ability to challenge the hegemony of the higher castes through his films Pariyerum Perumal and Karnan. More importantly, he is the only filmmaker to predominantly foreground the predicament of Dalits in the Tirunelveli district and interrogate the hegemony of the higher castes. He thus challenges the ‘Madurai formula,’ the sub-genre of films that focus on the upper caste culture/pride, particularly of the Thevar community. Mari is also notable for using the spaces of Puliyankulam, his native village, located 57 kilometres from Tirunelveli. Additionally, the urban areas of Tirunelveli are punctuated through iconic spots, like the Government Law College and the Palayamkottai Government Hospital, or statues like that of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (at the entrance of the Tirunelveli Bus Stand). Such a sustained engagement qualifies him as a Tirunelveli filmmaker, apart from his status as a significant Dalit filmmaker, next only in stature to the producer of his debut film, the iconic Pa. Ranjith. Since Ranjith and Mari are primarily mainstream filmmakers and use stars of various categories, there is a critique regarding the significance or centrality of the hero in their films and the concomitant masculinity.[5] This essay, therefore, focuses on the discourse surrounding Dalit masculinity in Ranjith’s Madras and Sarpatta Parambarai and Mari Selvaraj's Pariyerum Perumal and Karnan to argue for the specificity of masculinity in their films. This essay understands how their approach disallows the monolithic subsumption of masculinity driven by patriarchy among the upper castes. It also foregrounds Mari's specificity as a pioneering Tirunelveli Dalit filmmaker. Masculinity and Dalit masculinity In their essay, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities: A Study of Select Dalit Autobiographies,' Riya Mukherjee and Smita Jha analyse The Prisons We Broke (Aravind Malagatti, 2007) and Government Brahmana (Kamble, 2009). The authors draw from R.W. Connell and James Messerschmidt to engage with hegemonic masculinity as 'a pattern of practice…that allowed men's domination over women to continue.… It embodied the most honoured way of being a man…and it ideologically legitimated the global subordination of women to men'.[6] The authors also challenge such masculinity by pointing to the ruptures, as in the case of Malagatti's formidable and rebellious avva (grandmother), while acknowledging the resilience of the upper-caste male in the continuation of hegemony through caste patriarchy.[7] Nonetheless, Malagatti foregrounds the spirited response of the women of his family to the upper-caste faces of 'disgust' and 'contempt' at the public sphere of the village pond: 'My avva, chikamma and doddamma were no docile dolls! They, too, were fighters with self-respect, waiting for a spark to catch fire. There was not a single day when they returned from the lake without a fight.'[8] Mukherjee and Jha convincingly illustrate through the two famous autobiographies how complicit masculinity works through 'men who received the benefits of patriarchy without enacting a strong version of masculine dominance.’ This can be understood in the context of Dalit men, who adhere to hegemonic masculinity when it comes to subjugating their women.[9] Concurrently, they are oppressed by upper-caste men. Such complicity operates across genders, as in the case of the mother-in-law, who would join hands with her husband in harassing and tormenting the daughter-in-law. They also concur with Uma Chakravarti in understanding 'the reproduction of Brahminical hegemony which ultimately benefits only the hegemonic male.'[10] Mirroring the complicit is the willing acceptance to be a subordinate: Mukherjee and Jha delineate the relationship of Baby Kamble's father with the 'white sahib,' wherein he willingly accepts 'the colonial male in the hierarchy of masculinity' and his being (addressed as) 'just a boy,' while, when it came to her mother, ‘My father had locked up my aai in his house, like a bird in a cage.’[11] It was inevitable for him to assert his maleness. Marginalised masculinity refers to that of the hegemonic male in the racial/ethnic minority communities on the fringes, with concomitant socioeconomic challenges that grow from caste exclusion. In the context of Kamble’s milieu, the authors posit masculinity as ranging from the subordinate to the marginalised, and the way caste, gender and hegemony are intertwined and how oppression trickles down. As Mukherjee and Jha explain:

Through their detailed analysis of both autobiographies, Mukherjee and Jha convincingly argue that Dalit masculinity is not monolithic and instead keeps shifting its gear 'between the hegemonic and the marginalized,'[13] as per the context of their interaction. They further claim that the 'qualities of masculinities can also be located in the bodies of women, as the character of Aayi in Malagatti’s autobiography, challenging the overall association of masculinities with men.'[14] Their hope, mainly through the words of Kamble, that 'education can serve to bring about a change'[15] is tempered through the upper-caste male machinations of rendering the education of Dalits as 'undeserving and unequal,'[16] thus retaining and entrenching their hierarchy and hegemony. Ranjith’s and Mari’s films differ from the above conclusion as they endorse Kamble’s views regarding education by casting their protagonists as educated (Madras) or pursuing education (Periyerum Perumal) and are hopeful about the progress and upward mobility of Dalits. While the different hues of masculinity, as detailed by Mukherjee and Jha in the Indian context, are pertinent to Ranjth’s and Mari’s films, they further deconstruct and punctuate the nuanced differences in the Dalit masculinity of their main characters and the response of the spirited women in their movies. Ranjith’s Madras and existential masculinity

Madras revolves around a contentious wall that signifies the politics of Tamil Nadu and its larger-than-life banner-culture, in this case, signified by the portrait-painting of the slain political leader Krishnappan (V.I.S. Jayapalan). In this film, Ranjit engages with the reality of the lives of the Dalit community living in the rundown apartments of the public housing colony with its narrow lanes, further cramped by two-wheelers parked on both sides and the women who queue for the water supplied by the corporation. Even as the film is focused on the two factions fighting for the space of the wall, which symbolises political power and expediency, Ranjith, as is his wont, juxtaposes the gender equation by focusing on the protagonist Kaali (Karthi) and his argumentative and dominant mother (Rama) who rejects the alliances that come their way by finding fault with every girl. Kaali’s self-seeking grandmother is only concerned about the pocket money from Kaali for her betel leaves and nuts. Kaali and his father are reduced to witnessing the drama inside the house. Against this backdrop, Kaali meets Kalaiarasi (Catherine Tresa) and falls in love with her. Nonetheless, she is from the same locality and queues for water with the other women. Despite his manliness forbidding him from doing the task, a shy Kaali has to fetch water since there is no way he could go against his mother’s dictates. This shyness about doing household chores is contrasted with his white-collar job in a corporate house and his motorcycle, which informs us of his educated and middle-class background.

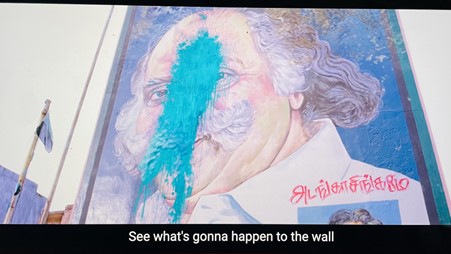

Figure 1. Kaali, along with his community, looks at the contentious wall. Source. Still from Madras, 2:10:09. Ranjith thus breaks the regressive stereotypes associated with North Chennai, where the film is based. The North Chennai community, generally depicted as permeated with gangsters and their accomplices, is inverted here by showing the hero as a simple but sophisticated young man who deeply cares for his family and friends, like Anbu (Kalaiyarasan) in the community. Anbu’s relationship with his young wife, Mary (Riythvika), is portrayed realistically. Though Anbu tries to show off his masculinity, particularly in front of Kaali, Mary is not one to hold back. Their relationship is revealed to be genuinely emotional and intimate as they are deeply in love with each other and their child. Nevertheless, the contestation for the wall and the politics surrounding it become the central preoccupation in the second half of the film. Understandably, the film follows a more predictable trajectory, keeping the requirements of mainstream cinema in mind, like songs and action, propelled by the murder of Anbu. However, Ranjith does not forsake the reality of the milieu and the systemic network of violence faced by contemporary Dalit youth. Thus, the film’s initial segments reveal the bold nature of its female characters; for instance, it is Kalaiarasi who comes forward to express her attraction and love for the reserved Kaali. Ranjit also overwhelms us with unequivocal and buoyant energy and the colourfulness of the lesser-seen culture of the Dalit community on the screen. The songs represent the community as an ensemble, dancing to eclectic tunes ranging from the local to the global (hip-hop/rap). This is unparalleled in celebrating the effervescence and the liveliness of the hitherto erased Dalit culture on the Indian screen. The film finally concludes the bloody war between the two factions with the wall being splashed with the blue colour of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s Republican Party. This action recalled the absence of space for the colour blue in Tamil Nadu politics over the last five decades. The political space had been dominated from the late 1960s by the Dravidian parties that came to power and sustained it through successive elections, and the rival factions of the D.M.K. (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam/Federation for the Progress of Dravidians) and the ADMK (Anna D.M.K./Anna's Federation for the Progress of Dravidians). These parties, which were marked by the colour of their party’s flags––black, red and white—disavowed the relative space of the blue for the Dalits and instrumentalised them for political/electoral purposes, mainly the local leaders of the community and the youth by creating factions among them.[18] Almost a decade after its release, Madras retains its energy because of its powerful portrayal of a slice of life of Dalit urban youth in North Chennai. Madras is noticeable because it forefronts Dalit empowerment, punctuating a movement forward from the details given by Baby Kamble in her autobiography regarding her father and his submissiveness to the British during colonial times and signifying the realisation of her hope in education regarding liberation by having for its protagonist a young educated man working in corporate industry.[19] The film is also unique for having the wall permeated with blue, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s colour and spirit, since the wall will now become part of a school for local children. Thus, Ranjith reaffirms Baby Kamble’s hope in education and the future of the Dalits and recalls the clarion call of Babasaheb Ambedkar to educate, agitate and organise.

Figure 2. The wall and the painting splashed with blue. Source. Still from Madras, 2:10:16. Since Madras, for its narrative, focuses on a wall, which is in the open in a public sphere at a crucial spot at the centre of the housing colony of the Dalits, it pivots on the homosocial world of young men, male party workers and politicians. The women occupy a significant place in the diegesis (equal to that of men during the first half of the film, where the detailing of the milieu runs parallel to plot progression). However, they are gradually relegated to the background and part of a crowd during the second half as the focus shifts to the gangster element of the fight between the rival factions, gory violence and bloody murders. Though the women come back, sporadically, in emotional scenes, mostly in songs, particularly after the meaningless loss of the lives of their beloved, the second half tows a relatively predictable line. Ranjith, however, marks the distinctness of his film by giving us a glimpse of the integrity of the friends and families, despite some of them being unaware of being exploited by both hardcore politicians and opportunists/betrayers among them. Dalit masculinity in Madras is undermined by the spirit of women who are willing to challenge men by speaking their minds, like Anbu’s wife, Mary, or Kaali’s mother, who is conservative in terms of her aspirations of a dowry from her son’s marriage or outspoken regarding her desire for a car, yet she commands respect from her son. The mother’s affection for Kaali is thus rendered ambiguous by not portraying her as the all-good sacrificing mother figure of Tamil cinema. However, when Kaali’s marriage is finalised through a formal betrothal ceremony, she denies the call for a dowry by Kaali’s uncle by asserting that the bride (Kalaiarasi) herself is a gift of precious gold. Similarly, despite her tenderness and middle-class life, Kalaiarasi comes out as bold in questioning Kaali regarding his values and the pursuit of good over evil, particularly in the scene when, after his dearest friend Anbu’s murder, Kaali is mulling over avenging the death of his generous friend who cared for the community more than his child by donating his meagre savings for the larger good. Kaali’s invocation of Anbu’s donation for the local carrom tournament is significant here. Sports like carrom, kabbadi, boxing and soccer mark the communal spirit and the vibrancy of the oppressed Dalits, apart from their exhilaration in their physicality, a trait characterised by its absence in the upper castes. They are marked by non-communal or ensemble games like tennis, as in Aalayamani (Temple Bell,)[20] or badminton in the song Parakkum Pandhu Parakkum/Balls that fly in Panakkara Kudumbam (Wealthy Family).[21] They are marked by sports contained through spaces or time, unlike the ubiquitous night matches with a swarm of men in Ranjith’s narrative universe and Dalit culture. Following that, Kalaiarasi, imagining dire consequences, asks Kaali whether he loves the dead (Anbu) or her more. Such a discussion also renders Madras unique since, in regular Tamil films, we do not see a woman questioning her man’s conscience, as that would be perceived as a damper when things are being set up expeditiously toward a climax wherein violence is inevitable and overlooked/justified in the move towards the resolution. In most Tamil films, such vital sequences will be framed by the pleading of the heroine/mother to deter the hero. Thereafter, Kaali comes to know of Maari (Charles Vinoth), a close friend and a confidante who was on their side, as the betrayer, one responsible for the violent killing of Anbu. Kaali challenges Maari when he is trying to seek votes in the locality after double-crossing and joining hands with Kannan (Poster Nandakumar), the politically expedient son of the leader who wants his father’s legacy of keeping out the local people from power to continue by protecting his father’s image on the wall. Kalaiarasi, despite the risk of taking on the sinister gang of powerful politicians and their hired killers, supports Kaali by standing with him, thus openly declaring her approval Kaali challenges Maari in the open regarding his betrayal. Still, he does not seek revenge by killing him, despite the mandatory action sequence in the end, but by capturing the wall by pouring blue paint on it. He is followed by his people, who pour blue and the earthen brown colour, thus fully covering the past leader’s massive face on the wall, announcing the end of an era and a new beginning. The letters on the newly painted wall now extol knowledge as a means for change. We finally see inside the school where Kaali and Kalaiarasi are teaching young students about the value of education along with political awareness and rationality. The Ambedkarite motto of education and awareness of and the fight for social justice is thus punctuated in the end, recalling and successfully realising the dream of Baby Kamble and her desire for and faith in education.[22] Therefore, in Madras, masculinity is played out as per the context in an existential way. If existence precedes essence for Jean-Paul Sartre, so also is it for Kaali.[23] He learns his lessons from life and acts accordingly, and predetermined values do not contain him. He is, nonetheless, positive rather than giving into a middle-class rumination and melancholy of alienation regarding the emptiness of life, unlike the French philosophers who meditated on the meaning of life. He derives energy from Babasaheb Ambedkar regarding an equitable and progressive society. Significantly, writers like J.P. Chanakya, known for their complex engagement with Dalit history and culture, have contributed immensely to the film.[24] Ranjith’s background as a student at the prestigious fine arts school in Chennai and, later, his experience as a signboard painter has made Madras a milestone in the history of Tamil cinema. The critical and commercial success of Madras led Ranjith to subsequently direct Tamil cinema’s superstar Rajinikanth in two major films, Kabali (2016)[25] and Kaala (2018).[26] The aura and the market requirements regarding a movie with a superstar subsume Ranjith’s predilection for giving importance to and empowering his women on screen in Kabali and Kaala. Nevertheless, Kaala is remarkable for portraying the protagonist Karikaalan’s (Rajinikanth) younger son, Lenin (Manikanadan), as the idealist-revolutionary who does not believe in the vengeful violence of his father’s era. Lenin plays a significant role as the founder of the Vizhithiru/Be Aware group. His comrade and girlfriend, Puyal (Anjali Patil), is rebellious and bold enough to take on the evil right-wing gangster/politician Haridev Abhyankar, aka Hari Dada (Nana Patekar). Kaala begins with a women’s protest against the devious Hari Dada’s attempts to evict them from their residences in Dharavi, in Bombay. Hari Dada’s construction company plans to build a modern high-rise building with flats for the rich as the area has become expensive since the immigration of most of the dwellers from the south, including Kaala’s family. In one of the critical sequences in the film, when the police violently attack the people of the community during a protest, the fiery Puyal is violently targeted for her politics and physically abused. The police strip her clothes off on a bridge, where she is caught alone. Instead of reacting like a typical Tamil woman who would go after her clothes to save her honour in front of men, Puyal reaches for a nearby stick and demonstrates her resistance. This particular sequence that undermines the trope of the 'damsel in distress' is remarkable for its intervention regarding Puyal’s challenge to hegemonic patriarchy and the violent oppression of women in Indian cinema. Here, too, Puyal, whose name means storm, draws attention to the existential reality of a Dalit woman who takes on her abusers rather than cave into the patriarchal expectations regarding karpu or chastity. However, as far as Dalit masculinity is concerned, the next film in Ranjith’s oeuvre, Sarpatta Parambarai, is remarkable. It was released in 2021 during COVID-19 on the Amazon O.T.T. platform. Sarpatta Parambarai and reflexive masculinity Sarpatta Parambarai is unusual among Ranjith’s films in reflexively addressing Dalit masculinity and drawing attention to the self-destructive element of alcoholism. Though one could argue alcoholism is pervasive, Ranjith delineates how unabated and ubiquitous caste hegemony and oppression force talented men to the wall and break their spirits. He uses the protagonist Kabilan (Arya) as an example. Kabilan is ambitious and hardworking regarding his desire to be a champion boxer like his father, Munirathnam (Kishore). Still, he resorts to desperate measures to heal his wounds in a heartless society, like drinking alcohol, becoming addicted, and forgetting his goals. The protagonist's mother, Bakkiyam (Anupama Kumar), is against his becoming a boxer because of the fate of his father, whom a rival group murdered because of the threat posed by his bourgeoning talent and fame as a boxer. Ranjith emphasises the physical activity of boxing as an expression of protest against casteist society. Despite group rivalry and jealousy, there is also the celebration of physicality/masculinity and the camaraderie of belonging to the community. But caste intervenes to create ruptures among fellow competitors from the opposite Idiyappan clan. It sucks their humanity and forces them to act in unethical and violent ways to stop Kabilan from defeating their representative in the boxing ring and attaining fame. Thus, Kabilan has to face the multiple challenges of outside forces who, in the name of caste, are trying to suppress him, his extraordinary talent, and his mother’s unwillingness regarding his boxing pursuits. She, understandably, wants him to lead a life that will be safe and secure. During the Emergency in 1975, Rangan (Pasupathy), a former boxer and a coach, a Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam/Federation for the Progress of Dravidians (D.M.K.) sympathiser and party member, organised a boxing match between Meeran (Sai Tamil), of the Sarpatta clan and Vembuli (John Kokken) belonging to the Idiyappan clan. Sarpatta clan members were shocked by the defeat of their icon.[27] Rangan promises to find a competitor for Vembuli and vows that Sarpatta clan members will never fight again if defeated. Initially, Rangan announces Raman as the Sarpatta boxer but, on coming to know he is a misfit, replaces him with Kabilan. This move angers Thaniga (Vettai Muthukumar), Raman’s uncle. Kabilan’s mentor, the Anglo-Indian Kevin (fondly addressed as Daddy (John Vijay)), in the meanwhile provokes the retired boxer, the crowd favourite, 'Dancing' Rose (Shabeer Kallarakkal). He loses to Kabilan, to the fans’ dismay, thus setting up the most anticipated duel between Kabilan and Vembuli. Kabilan goes after Vembuli and almost floors him in the fourth round. The next crucial round is in progress as the police arrive to arrest Rangan under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) for his D.M.K. affiliation. However, they are willing to wait until the end of the all-important match. When Kabilan is about to render his final, decisive punch to the losing Vembuli, the match is abruptly brought to a close because of violence unleashed by Thaniga’s gang members, who attack the assembled audience and target Kabilan and humiliate him by stripping him naked. Kabilan’s head is severely injured. Following that, Rangan is in jail, while Kabilan recovers, decides to quit boxing, and wants to fend for his mother and wife, Mariamma (Dushara Vijayan). Kabilan visits the incarcerated Rangan along with Rangan’s son, Vetriselvan (Kalaiarasan). While returning, Thaniga provokes Kabilan, who violently responds by attacking him with a sword. This act of violence results in six months of incarceration. Vetiriselvan, unlike his father, is an opportunist who shifts his affiliation to Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam/Anna's Federation for the Progress of Dravidians (ADMK), the party that was formed by M.G. Ramachandran (M.G.R.) when he split from D.M.K.[28] Vetri gradually rises in the party cadre, as does his illicit liquor brewing business. He also exploits the services of Kabilan without paying him his due. Kabilan becomes an alcoholic, creating trouble for his poor mother and anxious wife. Rangan returns from prison in 1977 when the Emergency was lifted, and he is shocked to see the overweight Kabilan and thinks of using another boxer to take on Vembuli. When the hurt Kabilan confesses to his mother how he has failed her both as a son and a fighter/boxer, she asks him to redeem himself through boxing. After a brief training with the legendary fisherman-boxer 'Beedi' Royappan, Kabilan returns and withstands the onslaught of Vembuli to win the title and glory for his Sarpatta clan.

Figure 3. Mariamma and Kabilan are happy about the marriage gifts. Source. Still from Sarpatta Parambarai, 1:25:47. Though Sarpatta Parambarai could be categorised as a sports film, it differs from others due to its detailing of North Chennai and Dalit life. More importantly, it addresses the topical issue of alcoholism among sportspeople, particularly in the Dalit community. For instance, Vinod Kambli, one of the rare cricketers in history to score back-to-back double centuries, has been in the news because of it, even recently.[29] The poet and the founder of Panther’s Paw Publishers, Yogesh Maitreya, in his scholarly and poignant analysis of the movie, convincingly argues for its uniqueness while informing us of the evil designs and insidiousness of the caste system and the inhumanity of the upper-caste people:

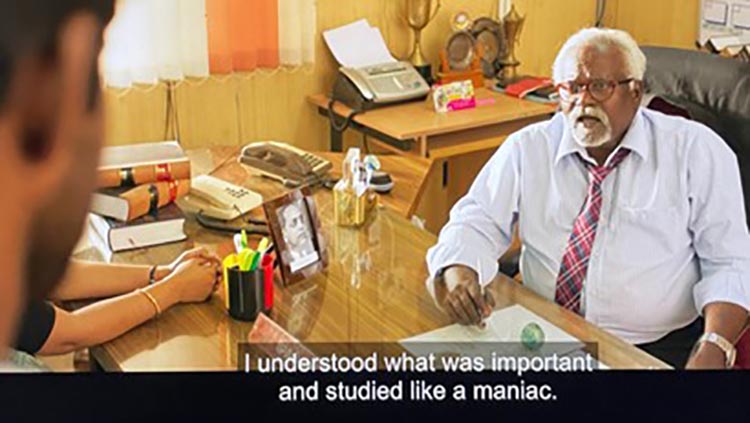

Observing Kabilan’s rise-fall-rise step by step, we see how a Dalit man, conscious of his history and downfall, chooses justice over manhood. It reflects how he establishes himself as a beautiful mind in a society that crushed his dreams, aspirations, and ability to think for himself. Kabilan does not fight for himself but on behalf of those Dalit men who were forced to self-destruct despite proving themselves worthy of respect and dignity.[30] Ranjith, therefore, acknowledges the reality and reflexively draws attention to the consequences of oppression by caste. However, he offers hope by focusing on the possibilities inherent in sensitive, committed and hardworking young men like Kabilan, who can change the course of their lives despite the seeming impossibility of it. Indeed, Ranjith himself, against all odds, went to the Fine Arts School in Chennai, following the path of Babasaheb regarding education. Kabilan, too, follows the same path, graced by his mentors, the Dravidian ideologically driven Rangan, and the iconoclastic 'Beedi' Royappan, from the fishing community, and more significantly, by the spirit of Dr Ambedkar, as cited by the framed photograph on the wall at crucial moments in the film. Thus, the Dalit masculinity in Sarpatta Parambarai is self-reflexive about the caste system’s surreptitious design to destroy the spirits of Dalit young men through the portrait of a community by an ensemble film, peopled by many colourful and talented characters. Mari Selvaraj: Pariyerum Perumal and Babasaheb’s path Mari Selvaraj’s debut film Pariyerum Perumal revolves around the life and times of the protagonist Pariyerum Perumal or Pariyan (Kathir), who falls in love with an intermediate upper-caste girl, Jothi Mahalakshmi or Jo (Anandhi). But he is ambitious about becoming a lawyer. While introducing himself, he imagines and quotes his name and his degrees, B.A., B.L. (Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Law). He adds a bar on top of his degrees (mele oru kodu), indicating they are unfinished. While the affirmative policies of the government make it possible for Pariyan to join the government law college in Tirunelveli city, the ambience within the college is mixed. On the one hand, he is humiliated repeatedly for his lack of knowledge of English or for the way he takes notes. More importantly, he is targeted by Jo’s cousin Sankaralingam (Lijeesh), a deeply entrenched casteist. On the other, he finds joy and solace in the company of Jo. Once, when she invites him to her sister’s marriage and insists on his presence, Pariyan borrows clothing from his friend and goes to the wedding. Jo’s father (G. Marimuthu), who was aware of Jo’s enthusiasm and penchant for Pariyan, guilefully asks her to be away on a chore, meets Pariyan, welcomes him and invites him to a private room in the wedding hall for a personal conversation. The song from Paruthiveeran,[31] performed by a music troupe to entertain the audiences in the marriage hall, alludes to the Thevar caste of the people involved. The innocent Pariyan, not knowing the deceitful ways of the father, follows him. The father queries about his village to ensure that he belongs to the Dalit caste. Communities, particularly the Dalits, live together because of fear and insecurity due to the ongoing violence of the upper castes for which generally there is no recourse. Therefore, one way to know about caste is by indirectly inquiring about the village a person comes from, particularly in the Tirunelveli region. In the meanwhile, Jo’s cousin Sankaralingam enters with his friends, who violently attack Pariyan, who desperately pleads for them to stop. Pariyan tries to protect himself by creeping into the corner of the room. After attacking him and throwing him on the floor, one of Sankaralingam’s hooligans urinates on Pariyan to leave the stench of upper-caste hegemony and violent hatred. He is unable to attend the wedding. This humiliating and inhumane event is highly traumatic for the dignified Pariyan, and it forces him to rethink his relationship with Jo. Nonetheless, he cannot cut her off as he likes her for her innocence. He becomes silent and unresponsive to her repeated queries regarding his absence during the marriage, and he does not reveal the reason. This is unlike much Tamil cinema, where the traumatic event will be repeated and reinforced, setting up the stage for the vendetta of the hero. Mari Selvaraj uses trauma for reflection, following the path of his idol, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. However, the taunting humiliations by Sankaralingam and his gang of rowdy students continue as they do not see Pariyan on the campus. Their caste-driven virulence makes them lock Pariyan inside the ladies’ toilet during the daytime when it is busy. They aggressively push him and close the door as he walks into the corridor. Pariyan is taken to task and brought to the principal (Poo Ram). The new principal, whose values are symbolised by the portrait of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar on the wall behind them, is unlike the earlier one, who had Mahatma Gandhi behind him and was cynical about Pariyan’s progress in the college. When Pariyan is asked to bring his father, he goes to his village Puliayankulam and locates his father (Nellai M. Thangarasu) among transwomen. They enact through songs and dance the erased history of the Dalit/Pallar community icon Immanuel Sekaran. His father plays the role of a woman with finesse, revealing why Pariyan initially felt shy and protective about his father and hired a guy (Shanmugarajan) to play his father in front of the principal. However, the Ambedkarite principal is compassionate; he recalls his struggles and encourages Pariyan to focus on his studies and encounter hardships without shying away. The principal then asks Pariyan, ‘Did I run and hide because they thrashed and chased me like a pig? I knew what was essential and sought extensive education—those who wanted to beat me now bow their heads in subservience.’[32]

Figure 4. The Ambedkarite Principal’s advice to Pariyan. Source. Still from Pariyerum Perumal, 1:55:38. When Jo arranges a reconciliatory meeting between her father and Pariyan, unaware of her father’s attempt to murder him, it resonates with Pariyan’s magnanimous answer to the father: ‘Your daughter will not respect you if she comes to know of your true self.’[33] What could be perceived as Pariyan’s submissiveness or effeminacy enables the most masculine of statements where Pariyan’s superiority comes through his regard for Jo’s feelings. However, it is she who will not let him go. Mari Selvaraj’s celebration of Dalit masculinity as predicated on dignity and justice reaches new heights when, in Jo’s absence, when she goes to fetch tea for them, her father repents and apologises for his misjudgments. After the apparent normalisation of relations between them, he is hopeful about improvement in caste relations in the future and says, ‘Let us see. We do not know what will happen in the future.’[34] The wiser Pariyan responds, ‘As long as you remain who you are and expect me to be a dog, nothing will change.’[35] The film ends with the camera going close and framing the two tumblers of equal height on the table after they leave, suggesting a possibility of equity and mutual respect through the jasmine flower in between. By precluding violence as a means to an end, Mari Selvaraj retains his focus on Dr. Ambedkar’s imperatives regarding education as providing the path for justice, equality and progress. Nonetheless, it is through the dignity expressed through his Dalit masculinity that Pariyan slaps Jo’s father’s face and his blinding and illogical caste pride and male ego. More importantly, Pariyan can make him realise his wrongly placed affection for his daughter, subsumed by caste patriarchy, and his impotence in controlling his daughter’s feelings. Pariyan’s masculinity resonates with Babasaheb’s faith in love across castes as the antidote.[36] Mari Selvaraj uses Pariyan’s patience in putting up with a series of humiliations and trauma to emphasise his genuine caring for Jo’s wellbeing despite her being spoilt. He also keeps the possibility of mutual affection and respect open. Thus, Pariyan personifies a thinking individual in front of whose compassionate masculinity the casteist pride of Jo’s family crumbles. Pariyan’s apprehensions regarding his father’s supposed effeminacy and profession as a crossdressing female performer come true when his father is stripped and publicly humiliated on the college campus and the road by Sankaralingam and his goons. His father’s humiliation is mirrored and prefigured by a similar shaming of Pariyan, except for the enclosed space of a room. Nonetheless, his belittling is also evident as he walks out. Instead of emaciating Pariyan, such undermining of masculinity adds to his resolve, like when he meets his recovering father in the hospital after Sankaralingam and his ruffian friends hurt him. Mari Selvaraj is able to harness the wounds and scars to keep the focus on Pariyan’s objective to study and subdue the empty caste pride and arrogance of the men in Jo’s intermediate upper-caste family through his resilient and thinking/wise masculinity. By disavowing a revenge scenario, Mari Selvaraj is able to draw attention to the centuries of injustice to the Dalits and their investment in creating a space for dialogue, as envisaged by the constitution and the vision of Babasaheb, with dignity, unlike the deprived and degenerate upper castes. By denying the catharsis, Mari, despite offering hope through the final image, also undermines the possibilities of change by punctuating the deadly hold of caste on the obstinate Jo’s father, who is emblematic of the unchanging rigidity of all upper-caste people. However, they pretend to be malleable to change and circumstances. The urinating phallus is thus rendered impotent, unable to reach humanity. The grace of Pariyan’s father, whose magisterial performance and suffering for the sake of his son empowers his son. It enables him to question the injustice of society, epitomised by the guilty and pathetic and downward-looking Jo’s father. Thus, Dalit masculinity plays a central role in Mari’s film in his rewarding efforts to shed light on the systemic injustice and irrationality of the caste system. In a way, Babasaheb’s spirit also guides Mari regarding dignified and socially just interdependence. Karnan, masculinity, and the domestic and public spheres While Karnan, with Dhanush in the titular role, has necessitated the focus on masculinity in a traditional way that seeks justice and violence, it is also remarkable for Mari Selvaraj’s invocation of Babasaheb’s dictum ‘Organize’–the third part of his clarion call: ‘Educate, Agitate, Organize.’[37] While Pariyerum Perumal remains true to the first two, Karnan focuses on the last two. Karnan references the frenzied and horrendous attack by the lawless and undemocratic upper-caste police on Dalits in Kodiyankulam village in Thoothukudi on 31 August 1995. It recalls the song Naan Yaar (Who am I?) from Pariyerum Perumal, where Mari elucidates a series of rampant hate crimes and prejudices against Dalits.

Karnan could be read as documenting the irreplaceable loss of Dalit lives for the legitimate demand of their fundamental rights, emblematised by their request for a bus stop near their village in a democratic country. The government-run buses must serve the needs of the people; here, the state, in connivance with upper-caste police, unleashes unrestrained and uncontrolled violence on Dalits, causing the loss of precious lives, property, and, most importantly, educational certificates. As the name alludes, Mari, in keeping with his authorial preoccupation, draws from mythos and the epic characterisation of Karnan in the Mahabharata. However, he inverts the inherent upper caste hegemony of centuries-old storytelling by reinventing Karnan as the lover of Draupathi (Rajisha Vijayan) and the beloved grandson of the elderly Yemaraja (Lal). Duriyodhanan (G.V. Kumar) reappears as the village chief who is friendly with Karnan and his grandfather despite their notoriety for impetuousness. Even if Karnan, in his anguish that the community’s voice is not heard, often takes it out on Draupathi, whose brother Vadamalaiyaan (Yogi Babu) often creates trouble for Karnan. Nonetheless, Draupathi stands her ground, supports her brother when she assumes he is right, and gives it back to Karnan. She also plays a decisive role in going after him when he leaves to join the Central Reserve Police Force at the critical stage of the climax, where the police force goes on a rampage. She also stands by him during the melancholic moment of impending doom when the state turns against a community. Further, she waits for him during the denouement to return from prison. She thus contributes to the ensconced space of hope where, along with the community, she dances with Karnan, looking forward to the future despite the deep scars in a casteist and inhumane society where oppression and violence against the underprivileged are the norm. In a similar vein, Karnan’s mother dares to throw the phallus-like sword that Karnan won by flying in the air, chopping a giant fish into two in a prestigious competition, publicly asserting his masculine pride, recalling a similar event in the Mahabharata but subverting the exclusion of Karnan because of his origins during Draupathi’s swayamvaram.[39] Karnan later retrieves the sword, symbolising his confrontational spirit regarding caste. However, his mother’s gesture indicates her desire to protect her son from the phallus of caste pride and violence. The act of throwing and submerging the sword in water underscores her agency. Even more critical is the hold of his unmarried elder sister, Padmini (Lakshmi Priyaa Chandramouli). She hits him to bring him to his senses from his loitering and unserious ways to make him aware of his responsibility. Further, she asserts herself to be the male who supports the family, and she rues her predicament of being an unmarried elder sister. Such a rendering of the hero figure as inconsequential and incapable of providing for the family is unparalleled in Tamil Cinema. Padmini’s characterisation and undermining of the presumed masculine figure as the head of the family, in this case, the father who is sidelined as incapacitated and jobless, is revolutionary, although a ubiquitous reality in Tamil rural life. In the public sphere, however, Mari recovers the loitering, purposeless masculinity of the iconoclastic Karnan and mobilises it as a rebellious spirit of the entire community, both women and men. This is instanced by the provenance of the initial protest against the non-stoppage of the local bus to accommodate the highly pregnant woman from Podiyankulam, Karnan’s village. Such inclusive masculinity, which in the garb of Karnan is willing to stand in the front and bear the brunt of the mindless brutality of upper-caste pride and arrogance, is necessary to tame the phallus of unchecked caste hegemony.

Figure 5. Police brutality and Dalit community. Source. Still from Karnan, 2:25:16. Dalit masculinity: North Chennai and Pa. Ranjith, and Tirunelveli and Mari Selvaraj Pa. Ranjith focuses on the milieu familiar to him––the urban space of North Chennai, to undermine the monolithic understanding of Dalit masculinity by deconstructing it into its various nuanced spatial and temporal hues against the backdrop of the rigid and unchanging upper-caste oppression. Madras portrays an educated Dalit man, sensitive to the existential realities regarding the instrumentalisation of Dalits in politics where they do not have a say, who challenge the system and its violence but ultimately privileges education and hope in the footsteps of Babasaheb. Sarpatta Parambarai shifts the focus from the exterior boxing ring to the interiority of Kabilan when he is devastated by the hostility of upper-caste rivals and fellow competitors, falls prey to their evil designs, and becomes an alcoholic. Ranjith’s intervention allows Kabilan to reflect on and recover his boxing skills by training under an icon from an equally oppressed fisherfolk community. The boxing finesse/masculinity, thus regained, with the advice of his mother and the help of his wife, while enabling Kabilan to retrieve the lost glory of his clan, is also an epitome of regrouping and standing tall against upper-caste hegemony after being unjustly and deviously floored. Mari Selvaraj is invested in the rural spaces of his village, Puliyankulam, in Tirunelveli, where both films are set. He also focuses on the adjoining semi-urban areas on the outskirts of Tirunelveli town, like the law college and the government hospital at Palayamkottai in Pariyerum Perumal. The busy urban spaces enable Ranjith’s focus on the existential realities of Dalit protagonists and their masculinity to navigate the adverse ground realities of caste-driven hatred and animosity among rival factions to reflect on their objectives driven by Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s dictums. Their focus is on a better future for themselves and the community where there is social justice and respect. In Mari Selvaraj’s films, the rural spaces of Tirunelveli inspire the echoing of Babsaheb’s dictum, ‘Educate, Agitate, Organize.’ Here, the preoccupation is about the space for dialogue and the claim for dignity and education among an emaciated upper-caste community devoid of any values except their fatuous caste pride. Dalit masculinity is again retooled as an all-inclusive organising factor that challenges the unconditional and unethical violence of the upper-caste people to seek justice in the mould of organising and agitating by an entire community that the conniving machinery of the upper-caste-driven state itself, exemplified by an inhumane police force, has targeted. Ranjith, the pioneer of Dalit cinema in the mainstream, is responding to the representation of the people of North Chennai as regressive and violent, earning their livelihood through violence, hooliganism, and bootlegging in Tamil cinema. Mari shifts the focus from the north to the deep south to respond to the Madurai formula or subgenre films. Tamil cinema scholars Karthikeyan Damodaran, Hugo Gorringe, and Dickens Leonard[40] have engaged with and expanded on Rajan Kurai’s meditation on films based in Madurai. Kurai analyses the exteriorisation and exoticisation of the south in the binary between the modern Chennai and the unruly south, personified by the 'sickle-bearing, country bomb-throwing [hench]men,'[41] mainly in Madurai, which is rendered as 'the domicile of the unlawful.'[42] Dickens focuses on films like Kaadhal (Love),[43] Parutheeveeran, and Subramaniyapuram[44] to argue for how 'violence is inherently portrayed as the dominant caste’s prerogative on screen,'[45] and 'systemic casteist structure [and] caste spaces.'[46] are reinforced through the deaths and decay––violent killing or mental derangement––of the protagonists. The dominant caste in Madurai subgenre films is marked as the Kallars/Thevar community, who are represented as taking pride in their 'self-image' as 'a martial community.'[47] As a response to the centrality of the masculinity and the melancholia surrounding the Thevars in the Madurai genre film, Mari posits the Dalits, specifically the Pallars/Devendrar Kula Vellalars of the deeper south––Tirunelveli as the binary opposite of Madurai. More importantly, he depicts the Thevars as the antagonists. Nonetheless, he alludes to the presence of various castes in Tirunelveli, as detailed by Damodaran, and deconstructs the idea of the monopoly of a particular community over space and its domination/hegemony. Additionally, he calls into question the recycling of Tirunelveli in much Tamil cinema for its waterfalls and pastoral lands and the caricaturing of Tirunelveli people for their distinct accent, which sounds like indigenous music to the ears in his films. Thus, Mari’s profound engagement with his village, Puliankulam and the spaces of Tirunelveli marks him as a Tirunelveli filmmaker, more specifically, an iconic Tirunelveli Dalit filmmaker. Notes [1] Madras, 148 mins, 2014, produced by K E Gnanavel Raja, S R Prakashbabu and S R Prabhu, directed by Pa. Ranjith, Disney Hotstar, accessed 13 Nov. 2023. [2] Sarpatta Parambarai, 174 mins, 2021, produced by Shanmugham Dhakshanraj and Pa. Ranjith, directed by Pa. Ranjith, Prime Video, accessed 13 Nov. 2023. [3] Pariyerum Perumal, 154 mins, 2018, produced by Pa. Ranjith, directed by Mari Selvaraj, Prime Video, accessed 13 Nov. 2023. [4] Karnan, 159 mins, 2021, produced by Kalaipuli s Thanu, directed by Mari Selvaraj, Prime Video, accessed 13 Nov. 2023. [5] A note on styling names: Pandurangan is the name of Ranjith’s father. So, he uses Pa as his initials, in a typical or classical British/Indian style, whereas Selvaraj is Mari’s father’s name and he uses it as his last name, [6] Connell and Messerschmidt, 'Hegemonic Masculinity,' p. 832. [7] Riya Mukherjee and Smita Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities: A Study of Select Dalit Autobiographies,' Sociological Bulletin 71(3) (2022): 454–70, specifically p. 457. Also see R.W. Connell and James W. Messerschmidt, 'Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept,' Gender & Society 19(6) (2005): 829–59, specifically p. 832, doi: 1177/0891243205278639. [8] Aravind Malagatti, Government Brahmana, translated by Dharani Devi Malagatti, Janet Vucinich, and N. Subramanya, Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 2007, p. 29. [9] Connell and Messerschmidt, 'Hegemonic Masculinity,' p. 832. [10] Uma Chakravarti quoted in Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 463. See also Uma Chakravarti, Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens, New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2018, p. 34. [11] Baby Kamble, The Prisons we Broke, trans Maya Pandit, Hyderabad: Orient BlackSwan, 2009, p. 5. [12] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 468. [13] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' pp. 468–69. [14] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 469. [15] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 469. [16] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 468. [17] 'Existentialism,' Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, 6 January 2023, accessed 27 Apr. 2023. [18] For details on the Dravidian parties and their politics, see Narendra Subramanian, Ethnicity and Populist Mobilization: Political Parties, Citizens and Democracy in South India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999. [19] Mukherjee and Jha, 'Reconstructing Dalit Masculinities,' p. 461. [20] Aalayamani, 154 mins, 1962, produced by P S Veerappa, directed by K Shankar, 1962, YouTube, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [21] Panakkara Kudumbam, 171 mins, 1965, produced by T R Ramanna, directed by T.R. Ramanna, YouTube, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [22] J.P.S. Thomar, Dr. Ambedkar's Thoughts on Education, New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, 2010. [23] Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Sarah Richmond, New York: Washington Square Press, 2021. [24] Find his books at: J.P. Chanakya, Panuval.com, 29 December 2023. [25] Kabali, 152 mins, 2016, produced by Kalaipuli S Thanu, directed by Pa Ranjith, IMDb, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [26] Kaala, 159 mins, 2018, produced by Dhanush, directed by Pa Ranjith, IMDb, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [27] Gyan Prakash, Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy's Turning Point, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2019. [28] Narendra Subramanian, Ethnicity and Populist Mobilization: Political Parties, Citizens and Democracy in South India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999. [29] Press Trust of India, '"Threw Broken Handle Of Pan": Vinod Kambli's Wife Accuses Him Of Assault,' NDTV Sports, 5 February 2023, accessed 13 Feb. 2023. [30] Yogesh Maitreya, 'Sarpatta Parambarai shows Dalit Masculinity in Transition,' Indian Cultural Forum, 25 January 2022, accessed 13 Feb. 2023. [31] Paruthiveeran, 162 mins, 2007, produced by Ameer, directed by Ameer, IMBd, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [32] Pariyerum Perumal, 1:51.35. [33] Pariyerum Perumal, 2:15.57. [34] Pariyerum Perumal, 2:22.24. [35] Pariyerum Perumal, 2:22.31. [36] B.R. Ambedkar, Annihilation Caste: Annotated Critical Edition, London and New York: Verso, 2016. [37] Arun Kumar, Hari Bapuji & Raza Mir, '"Educate, Agitate, Organize": Inequality and Ethics in the Writings of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar,' Journal of Business Ethics 178(1) (2022): 1–14, doi: 10.1007/s10551-021-04770-y. [38] Karthikeyan Damodaran, 'Pariyerum Perumal: A Film That Talks Civility in an Uncivil, Casteist Society,' 12 Oct. 2018, Wire, accessed 13 Feb. 2023. [39] John D. Smith, The Mahabharata, London: Penguin, 2009. [40] Karthikeyan Damodaran, and Hugo Gorringe, 'Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema,' South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (free-standing articles) (22 Jun. 2017): 1–29; Dickens Leonard, 'Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films,' South Asian Popular Culture 25(2) (2015): 155–73. [41] Rajan Krishnan, 'Imaginary Geographies: The Makings of "South" in Contemporary Tamil Cinema,' in Tamil Cinema: The Cultural Politics of India's Other Film Industry, ed. Selvaraj Velayutham, 139–53, London: Routledge, 2007, specifically p. 143. [42] Krishnan, 'Imaginary Geographies: The Makings of "South" in Contemporary Tamil Cinema,' p. 146. [43] Kaadhal, 150 mins, 2004, produced by S Shankar, directed by Balaji Shakthivel, IMDb, accessed 21 Dec. 2023. [44] Subramaniyapuram, 145 mins, 2008, produced and directed by Sashikumar, YouTube, accessed 29 December 2023. [45] Leonard, 'Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films,' p. 162. [46] Leonard, 'Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films,' p. 161. [47] M.S.S. Pandian, 'Dalit Assertion in Tamil Nadu: An Exploratory Note,' Journal of Indian School of Political Economy 12(3–4) (2000): 501–17, specifically p. 503. |

|