|

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific

Issue 42, August 2018 doi: 10.25911/3CWK-4R12 |

|

Keith Stebbins, John Hughes, Laura Zimmer-Tamakoshi, Margaret Jolly

Christine grew up in Sydney, the eldest of three children. While at High School, she wrote a novel with a school friend about taking horses to gymkhanas which was published. It was titled Six Horses and a Caravan. She went on to Sydney University where she studied Anthropology and Bahasa and where she completed a first class Honours degree. She met a fellow student Tony Voutas during her third year when they were both on a University Australia–Indonesia Association committee. Tony was a presenter during a conference and spoke of his patrol officer experiences in PNG. Christine started a Master's program on Indonesian literature and moved to Indonesia to study. Christine's friendship with Tony blossomed into Tony asking Christine to marry him while he was campaigning for elections in PNG. Tony was elected as a Member of PNG's colonial version of parliament, the House of Assembly. Christine left Indonesia and flew to Morobe in PNG in 1968 and travelled around the Morobe province while Tony campaigned. Tony's friend, Barry Holloway attended their wedding in Lae, after which they returned to their home in Mumeng. Tony won in the election and was appointed as the Morobe Province regional member. Christine and Tony set up homes in both Mumeng and Port Moresby. After four years they moved from their home in Mumeng to a home in Lae. Christine travelled with Tony flying around around the Morobe province and to the quarterly Assembly meetings held in Port Moresby where they had many hair-raising experiences. They both enjoyed staying with Barry Holloway in Kainantu. Tony and Barry helped establish the Pangu Pati with Michael Somare and his PNG party members. Together they prepared for the 1972 elections. Christine was thrilled to be part of the team and worked as typist, speech writer and researcher in the Member's wing of the Parliamentary building and ended up working in 'the Chief', Michael Somare's office. Tony and Christine enjoyed holidays in Australia and throughout Europe and Asia. Christine's work at this time generated a real interest in Law, and so she enrolled in a Law degree program at UPNG where she became friends with Jean Zorn, a young Law lecturer at the University. Jean's husband Steve Zorn was working on constitutional matters with Tony and the House of Assembly. Christine celebrated PNG's Self-Government in 1972 and contributed to PNG's wonderful constitution with an entrenched Bill of Rights and detailed enforcement provisions, something of which she was extremely proud. It was while Christine was at the University of Papua New Guinea that Tony and Christine decided to divorce. Tony returned to a job in Canberra, while Christine continued her law studies in Port Moresby. Christine enjoyed the company of the PNG law students such as late Josepha Namsu Kiris (formerly Kanawi), Kina, Francis, Michael, Sao, Roa and Loani. Roa took Christine and his American lecturer to his village at Kapari that became Christine's 'PNG village home'. She also enjoyed trips to the homes of other students during holiday periods. She went with Mora to Ponam in Manus, and with Paul and his wife to South Bougainville. When the Zorn's left PNG and Christine had graduated with a law degree from UPNG, Christine travelled to Canberra, when she married Pete who owned a dairy farm in the Bega valley. Christine learned a lot about mechanics, the servicing and repairing of motors as well as being a farmer's wife—cooking and looking after the house. Christine adopted a dog called Tappet, who became her soul mate and moved places when Christine moved. Pete and Christine bought an additional farm, Dundundra, close to Wyndham. When Pete fell in love with another woman, they divorced and Christine obtained Dundundra and ran the farm with the help of a neighbouring farm family who 'adopted' Christine into their family. Christine's adopted family looked after Dundundra when Christine returned to PNG to research Village Courts with Jean and Steve Zorn in July 1988. Christine was delighted to catch up with her University friends. Josepha was now Secretary of the Law Reform Commission. Christine was acknowledged by Michael Somare at a function to honour Pangu Pati's 21st Birthday in 1996 where Christine was seated at the official table. Christine took up an offer to work at the Law Reform Commission, and arranged for her farm to be looked after by her neighbours. Christine loved her 'welfare law' work at the Law Reform Commission and struck up a professional friendship with Jim Fraser, the First Legislative Counsel, who ignited her love of legislative drafting. She became a close friend of Roslyn, the Director of the Legal Training Institute when Christine studied at LTI and was admitted to the bar. Some of the key contributions made to PNG were her work on PNG's fisheries legislation and regulations; HIV/AIDS administrative structure and law, ethics and regulations; environmental law and regulations. She also worked as Acting Assistant Secretary (Policy & Executive) at the Justice Department's Attorney-Generals office during this time. Christine first carried out two months of intensive drafting for Nauru's fisheries management, maritime boundaries, and an establishment of a statutory authority. Following that work she became the Legislative Counsel for Nauru in 1998. She was then appointed Acting Secretary for Law on Nauru which has the following duties: Registrar of Banks, Registrar of Corporations, Head of Customs and Immigration and Receiver of Wrecks. Her work gave her the opportunity to interact with most Pacific countries on fisheries and HIV/AIDS legislation. This led to her being in demand for consultancy work throughout the Pacific.

Christine's first consultancy position was on PNG's National HIV/AIDS Support Project where she worked for two years reviewing policy and legislative reform in relation to HIV/AIDS. In 1992 Christine and Carol Jenkins had drafted a Bill to establish a National AIDS Council that was rejected by Cabinet at that time, and was subsequently adopted. It was obvious to the National AIDS Council that laws relating to homosexuality and prostitution needed to be decriminalised if effective support programs could be implemented. Christine prepared the HAMP Act that was finally passed by Parliament in 2001 that protected the confidentiality of those with HIV/AIDS. When Christine left NHASP, she was approached from time to time to do other reform and drafting work—on the relationship between national and provincial laws, some serious reviewing and upgrading of environmental law. But she never lost her interest in and passion for gender and human rights. She was at one stage employed directly by UNAIDS, the UNDP Pacific Centre and the Pacific Regional Rights Resource Team for desk work in Suva on a review of the HIV, Ethics and Human Rights in fifteen Pacific Island Countries. She also requested to attend and present at various workshops and meetings in PNG and in the Pacific region generally. When she started PhD research at The Australian National University, she was able to pour it all out in her chosen topic, 'Sex, Gender and the Law in Papua New Guinea'. After many long years her thesis was eventually published as a book by ANU Press, available as a free download: Name Shame and Blame: Criminalising Consensual Sex in Papua New Guinea.

Christine had been hired to carry out drafting work on PNG environmental laws when she became ill with a lung disease that made her very weak physically. She was unable to run her farm and continue her consultancies at Dundundra and so she sold the farm to her neighbours and moved to a small home on Coochiemudlo Island in Brisbane where she had many friends and where she could continue her consultancies and her writing. When her illness made it unable for her to stay in her Coochiemudlo home she moved close to her brother's home into a nursing home in Bangalow where she passed away on 22nd July 2018. Christine donated her library to the Madang Divine Word University.

Dr. Christine Stewart hoped that PNG would decriminalise homosexuality and prostitution and dedicated her research to this goal. Christine's book 'Name Shame and Blame has been quoted in the United Nations as giving the reasons why decriminalisation of homosexuality and prostitution should take place in PNG. Dame Carol Kidu, when she was Leader of the Opposition in Papua New Guinea's government, also called for this needed Law Reform. Christine and our time in PNG Robin Jenkins My husband Mike and I were lucky enough as adults to stay with her in Lae in 1969 en route to the Eastern highlands where we were working. She was so generous of spirit and for a few weeks we stayed in their home together with Michael Somare and witnessed the embryonic stages of the Pangu Pangu independent party. We witnessed her passion in helping Michael and the Papuan people, a selfless passion that continued all through her life in the South Pacific and Melanesia. Wikipedia credits Michael Somare, Tony (her first husband) and friend Barry as starting the party but that is not correct. It was also Christine's hard work and open house that was important. Her passion continued with her law degree and the writing of the constitution for New Guinea. We were lucky enough to have time together at ANU and down the south coast in recent times. And we were present for the launching of her recent book—Name, Shame and Blame—a great effort! I have so many happy memories of our life together. Christine Stewart Camilla Chance Soon after Christine Stewart and my brother Peter Chance became partners, my brother brought her to stay with me, my husband Adam and our children Ruth and David. I am Peter's older sister. My children and I immediately adored Christine, and, as we were extremely close with my brother already, Christine was welcomed from our full hearts as my sister-in-law and my children's forever-aunt. Sometime later, my husband, my children and I spent our very happiest holidays enjoying Green Machine on the property Christine and my brother shared. As a result, my children, who were extremely young, requested that we put in our Wills that if we died Christine and my brother would bring them up. But no sooner had I put it in my Will than we visited Dundundra again, and I asked what was wrong. Christine said my brother was too interested in her best friend. I spoke with my brother in Christine's support, but he shrugged. Only a few days after we arrived home, Christine and Pete broke up. My children had briefly felt so joyfully secure about their future that my exceptionally strong motherly instinct, rightly or wrongly, prevented me from telling them the news. I believed that having such happy emotional security over a number of months would stand their characters in good stead. But the price for me was heavy. Christine stayed away because she was afraid of letting out the truth. For a while, Christine acted as my editor, so I took her to a Women's Writing Retreat in Italy where she made a number of American friends who valued her highly, and with whom she kept up. Our hostess at that time will host a similar Retreat, but in the United States, this year, where she plans to feature Christine's writing. I have frequently told Christine I saw her as my best friend. She has invariably replied, 'That's very sweet'. She enjoyed the support of, and supported, so many good friends that I never had a hope of her seeing me as her best friend. Importantly, also, she spent much time among nations overseas. Nations, not to slight their own abilities, she did serve hugely with her legal skills. Christine's last months have been spent in Feros Village, a nursing home close to her brother Steve, his wife Hilary and also to me. In Feros Village, Christine has been the champion of many virtually helpless patients, saying things like, 'You don't have to eat that'. Both my children have visited her there. Twice she tried, to my knowledge, to starve herself to death, but then rallied, had her bedroom beautifully painted and decided to write her memoirs. When these were nearly finished, I mentioned (being, I understand, not the only person to do so), that, if she continued to write sweetly, no one but her friends would read her work. I laughed to myself like a drain when, in her last chapter, she lashed out against the system and in favour of euthanasia. The right tone was difficult to achieve, and ironically kept Christine interested in life again for some time. I think her outspokenness in this last chapter has turned her earlier sweetness into a strength. The contrast between the two sections adds weight and a sense of integrity to what she finally says. Christine and I used to play a game. When, queen-like, she felt like seeing me, she summoned me by email to Feros Village. She then would dress in her best pyjamas and hold court as if nothing were wrong, ordering me a soy Milo. I felt that her sense of power while doing this was important. Despite the mock formality, our conversation always had depth and sincerity. Who could not have depth and sincerity with Christine? But then considerable time lapsed without an invitation. At last I could bear the lull no longer, and turned up anyway. Christine exclaimed how glad she was to see me, and said she could no longer email, because she had given away her computer. That day we ran out of conversation, and I asked if she would like me to say some Baha'i prayers. Christine replied, 'Why not?' (She had always said to me that, in this regard, she liked to keep her options open.) She particularly liked one prayer, so I said it three times, hoping that, with her brilliant mind that I enjoyed so much, she would remember it by heart. A few days later, I said to my husband, 'I must see Christine today'. He drove me to Feros Village and left me there. Christine could not speak above a whisper, and much of the time could only move her mouth. However, as we all know, her mind was as sharp as ever. After a while, I found myself saying Baha'i prayers again. As I finished, I said Christine's favourite prayer and then went into a 'Prayer for the departed':

I felt Christine to be on a real high, and she said quite loudly, 'I want to go Now!' To make absolutely sure, I asked, 'You want me to go?' 'No!' she said loudly, 'me!' and, though she had only moved the odd finger before, now she moved her arm with unusual vigour and put her hand on her chest. We both felt I should leave her to compose herself peacefully at that moment. I sat by the door of the 'Feros' building and called my husband on my mobile. Then I realised I'd left my handbag in Christine's room, and returned along the passage and crept in. Christine grunted at me loudly. I knew she meant, 'Hello, and who are you?' I replied, 'It's Camilla. I left my handbag behind!' Christine made a satisfied grunt. But it was a comedy, after the solemnity. And Christine was always a great comedian. Next morning, the text from Steve came on my mobile: 'Hi Camilla, Sad to inform Christine passed away peacefully this morning. Hilary and I were in attendance. Regards, Steve.' Early days Jean Zorn Christine and I met in 1973, and immediately became friends—which means we have been in each other's lives, hearts and minds for 45 years. I find now that it was not nearly long enough. Every day since she died there has been a reason to wish she were still here. And there will continue to be every day going forward. Rather than rage on at that, I want to go back to the beginning. We met in the class in Land Law at UPNG. I was the professor. Christine was one of the students. So was Josepha Namsu Kiris. They were the only women in their class. I was the only woman among the law faculty. No surprise we had a lot to talk about. Everything Christine would be, she was then. Oh, drafting some of PNG's most important legislation was still in her future. As was Dundundra. And Name, Shame and Blame—her great work of sexual politics and scholarship. But the vivid and forceful person who would accomplish all that was complete and entire even then. She was a force. She took up space. And not just because she was a handsome big-boned woman, but because she was a strong and vital personality, with passionate enthusiasms and an unbounding interest in and acceptance of everyone around her. Even her biases—she distrusted mainstream medicine, for example—were exuberant and well-meant, and she never could bring herself to truly hate anyone; she found ways to forgive, or at least to tolerate, even the people who did the things she despised. She was powerful, but utterly unselfconsciously so, and her power was unlike that of many of the expats we met in Papua New Guinea back then; the Aussies especially had the unfortunate habit of taking over the conversation, the direction, the whole room, especially when almost everybody else in the room was shorter, slimmer and browner than they—a not infrequent occurrence in Papua New Guinea. Christine's power came from her generosity of spirit, from the excitement with which she embraced the moment. She took up the life of a Uni student in PNG with gusto. She wore meri dresses, she shopped at the public market, she and Tony built their house in Hohola, which was decidedly not an expat enclave, she spoke Tok Pisin fluently. And none of this was planned or affected, or done for show. She was living in PNG, and so she was going to be PNG, and that was that. She didn't put a lot of thought into it. She didn't call attention to it. She just did it, as if it was the obvious, the natural thing in the world for anyone living in someone else's country to do. The Law Faculty class that included Christine and Jo was special. Not just because they were among the country's first ever indigenous lawyers, and, even more important, the very first to be wholly educated at UPNG and not down in Oz or off in UK, where nothing about customary law or colonial law or anything remotely relevant to PNG was ever taught. Not even because, once they graduated, they would fill every high-ranking legal post in PNG's newly independent government; but because they were smart and dedicated and funny and curious and open. Just the sort of guys to appreciate a pal like Christine. Sure, she slept with a few of them. Who wouldn't? But no hard feelings—mostly. They were all comrades in this great new adventure—the law, the beginnings of independence, all happening just at the right moment—when they were young and educated and ready for whatever would come next. So, the memories:

* The momentous trip to China, when the consul lost our passports, leaving Bruce Ottley and me, the Americans, briefly gaoled in the Hong Kong airport, while Tony and Christine had tea at the Australian High Commission; * 'Integrating' the private bar at Jackson's Airport: like most formerly white drinking establishments then in PNG, it effectively shut out Papua New Guineans, by forbidding thongs (that footwear ubiquitous on Papua New Guineans, but seldom seen on expats). A good part of that famous UPNG Law Faculty class joined us for a couple of rounds in that bar one afternoon, celebrating the end of exams, and every one of us, of course, in thongs. Once freed from the constant criticism of an oppressive Australian childhood, Christine lived life her way. No compromises. Just lots of drama and love and caring. I want to be angry at her for leaving us so soon. But, she died the way she lived, so how can I be? Memories of Christine Stewart Daniel Emlyn-Jones One Christmas five or six years ago, Christine visited my home in Oxford. She'd been on a grand tour of the US and other parts, going on conferences and things like that. She arrived when we were all about to go carolling around the streets. The fire was roaring, the mulled wine was simmering, and at that moment she fell in love with the British Christmas. She said it reminded her of Beatrix Potter. We had a delightful time. My family and other friends adored her and for a few weeks she was a wonderful part of the family. Several years later in 2015, when I visited her on Coochiemudlo Island where she'd retired, she was still telling everyone the story of that memorable Christmas. Some people even came up to me and said 'Ah, you're the Daniel where Christine spent that memorable Christmas!' or words to that effect. She had been diagnosed with the lung-fibrosis by that point, but it didn't stop her chatting nineteen to the dozen and taking me around the island, not to mention to the wonderful Red Rock Café for dinner. She was getting weaker and coughing by then, but it didn't stop her enjoying herself and making sure everyone else did too. We'd first met in 2005 at Burgmann College, ANU, where she was doing her PhD. My friend Jock and I naturally gravitated towards her. Her energy was warm, strong and kind and she had a great sense of fun. Her personality filled a room and we always looked forward to her presence. When she visited my friend in Singapore, he said she was the 'loveliest person who'd ever visited'. She did have a very bossy side as well. If she thought something should be done a certain way, it should be done that way, end of story. I remember when an Italian friend, who lived near her in the New South Wales countryside, came to visit Burgmann. She was packing the boot of a car, and Christine was managing the entire process in classic Christine juggernaut style. The Italian lady turned to us and said, 'Gor she's bossy isn't she!?' I never saw this as a failing in her character though. It was simply how she was. I suspect this assertiveness and strength, coupled with her passion for human rights work, made her a formidable force for good in her legal work. She was also entirely accepting and supportive of gay people, which came over very strongly. As a gay man, a part of me felt very safe in her presence, because I knew she was a loyal friend, but I also knew she was a friend who would fight my corner if she had to. Her passion for human rights and a wish to make the world a better place for others was something I greatly admired about her. I remember when we had a prayer service in college for victims of the Tsunami, tears were streaming down her face. She felt other people's suffering as if it were her own. Christine wouldn't let herself get pushed around, and sometimes she dropped relationships which became difficult. Sometimes I sympathised with her decisions to put certain people behind her, and sometimes, especially when I knew the people, I felt she was being obstinate. What I always deeply admired about her though, was that even when she found people difficult, on a deep level she fought hard to be positive and kind. A big part of her wanted to heal her relationships, and it was this human struggling, which I relate to so strongly to in my own life and the relationships I find difficult. She was a real inspiration to me. We skyped fairly regularly from the first part of 2016 until a month before her death, and she was always a delight to talk to. However physically ill she was feeling, she'd always be smiling and telling her seemingly endless collection of fascinating stories in sprightly Christine style. She always said she wasn't scared of death, but was ready for 'the next Bardo'. It was frustrating that she had to wait so long, because of the illegality of assisted dying. She had the wonderful loving care of her brother and sister-in-law, Steve and Hilary, not to mention her carers in the nursing home, but she was ready to go long before she did. We talked extensively about ways to do it. I suggested sending her gin infused with mandrake root, but we weren't sure of the effects of mandrake. I suggested bringing Nembutal into the country, but she pointed out that the sniffer dogs would find it, and I'd end up in a charming Australian prison! What she did do was to entirely convert me to the necessity of assisted dying. If there is a fitting memorial for Christine, it should be to change those wretched laws for good! Christine once said to me that after she died, she'd 'just be a prayer away'. It was a sweet and motherly thing to say, but I think she meant it. I do believe in an afterlife, and at the risk of sounding nuts, I'm sure Christine is looking over my shoulder as I write these words. Death isn't the end, and for all of her family and her friends, Christine will always be 'just a prayer away.' Remembering Christine Stewart Keith Stebbins I met Christine for the first time when I moved into a block of units in Airvos Avenue in Port Moresby in the late 1980s. Christine's flat was above mine, and she introduced herself in the car park and asked if she could 'pop in' as she enjoyed my music when I played the piano. She asked me to play her favourite tune, The Windmills of your Mind, which I frequently played for her. We shared a common interest in jazz, and we went to a jazz festival at Merrimbula in New South Wales. We stayed at her farm at Dundundra, which was the first of several visits to her farm. I convinced her that the best place to build her home was the ridge that overlooked the waterfall and national forest. A special memory I have is Dr Carol Jenkins and Christine, on my verandah, working on the proposal to establish a National HIV/AIDS council, while I plied them with coffee and prepared meals for them both. I presented the Department of Education's proposal to establish Special Education Centres and train teachers which was endorsed at a Cabinet evaluation meeting that I attended with the Secretary of Education. That same meeting chaired by Julius Chan rejected the HIV/AIDS National Council proposal presented by Dr Carol Jenkins. It wasn't until a number of years later that Cabinet adopted the proposal prepared by Christine and Carol. In Christine's memories she refers to me as a 'brother' and I am honoured to have been given that title. She shared her trials and tribulations with me, and it was over one of the many dinners she had at my home that I suggested the topic of her PhD. She wrote in the cover of her book, Name, Shame and Blame, that she gave me:

When she became sick and was unable to live on her farm, she bought a home on the small island I live on in Brisbane, and I took her to her numerous doctor appointments, which were sweetened by us always enjoying lunch together at a variety of scenic restaurants. When she moved into the nursing home in Bangalow close to her brother and his wife, I made a number of visits when I would take her out for lunch at the local pub. The last was one a week before she passed away. That was the only visit that she didn't join us for lunch at the local pub. Her favourite poem was Warning by Jenny Joseph:

With a red hat which doesn't go, and doesn't suit me. And I shall spend my pension on brandy and summer gloves And satin sandals, and say we've no money for butter. I shall sit down on the pavement when I'm tired And gobble up samples in shops and press alarm bells And run my stick along the public railings And make up for the sobriety of my youth. I shall go out in my slippers in the rain And pick the flowers in other people's gardens And learn to spit … Christine certainly spat, and pressed alarm bells and rubbed a very powerful stick against public railings over the need to address the social inequalities that exist in Papua New Guinea that will resonate for many years to come! Memories of Christine Stewart John Hughes My memories of Christine date from our mutual involvement with the Moresby Arts Theatre, or as it was then known, the Moresby Theatre Group in the 1980s. She was a formidable actress with enormous skill and stage presence. Her performances in Lilies of the Field and I'm Still Here were particularly memorable. She and I, together with Kathy Lepani, began work on Edward Albee's brilliant play, Three Tall Women, but unfortunately, this never reached fruition for reasons beyond our control. Christine was playing the role made famous by Maggie Smith in the West End. Such was her talent. Christine and 'engendering' violence Laura Zimmer-Tamakoshi I first met Christine at an informal session on gender violence at the 2006 ASAO meeting in San Diego CA. During the session, I suggested the broader, more active concept of 'engendering' violence. Sometime later, Christine and her co-organiser Dorothy Counts invited me to be a discussant for the proposed 2007 working session on 'Engendering Violence'. I declined, saying I would rather contribute a paper on a topic I'd been researching for over twenty years: 'Troubled Masculinities and Gender Violence in Melanesia' (2012). It was at the 2007 ASAO meeting in Charlottesville VA that our friendship took off. Visiting a local race horse farm with Steve and Jean Zorn, socialising and talking gender and anthropology at the book tables and over dinner, we discovered mutual interests and experiences, both having lived and taught in Papua New Guinea in addition to doing years of research there.

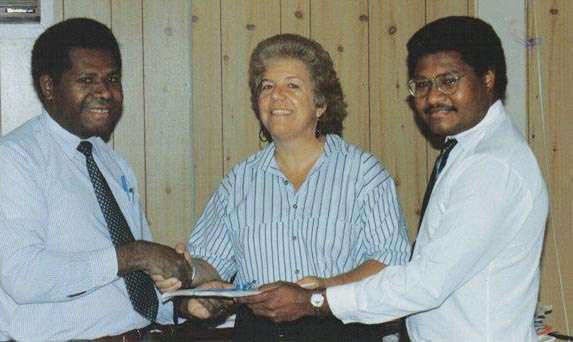

The friendship grew at ASAO and ESfO conferences in settings as far-flung as Canberra and Bergen and in meetups in Papua New Guinea and ANU. In Port Moresby, Christine met me at the UPNG bookstore (where we bought a ton of books) and took me by car to several area shops and then to visit her longtime friend Josepha Namsu Kiris. Christine and Jo were students of Jean Zorn's at the UPNG Law School, Christine receiving her law degree just after Papua New Guinea became Independent in 1975. I first knew Jo as Josepha Kanawi back in the late eighties when I taught at UPNG and attended WIP meetings, the acronym variously referring to women in politics, power and parliament. For two hours, the three of us ran a buai maket ('betelnut market') in front of Jo's home.

In 2012 and 2013, I had the privilege of being both an outside examiner of Christine's doctoral thesis (2011) and a reviewer of the revised version of that thesis that would become Name, Shame and Blame (2014). Focusing on discrimination against sexual minorities in PNG, Stewart once again reveals her humanity. It is evident throughout that she was readily accepted by gay males and prostitutes: gay males accepting her in the role of 'mama', a sympathetic nonjudgmental listener; prostitutes responding positively to Christine's openness and self-consciousness, or reflexivity, about being a relatively 'well off' older, expatriate woman who never had to sell sex. Relying on her sensitivity, Christine built the necessary rapport to go beyond simple questions and to gently probe the negative experiences and discrimination suffered by these women. Vale Dr Christine Stewart Margaret Jolly I first met Christine in 2004 in the company of the late John Ballard—two people who had long lived in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and who loved the place and its peoples. Christine first went to PNG in 1968 after graduating from the University of Sydney in Anthropology and Indonesian and Malayan Studies. There she forged a formidable reputation—in the pre-independence struggles for racial justice and the founding of the Pangu Pati which led to an independent PNG in 1975, as a graduate of the law program at the University of Papua New Guinea (gaining her LLB in 1976), as a dedicated worker for the Papua New Guinea Law Reform Commission and as the person who drafted the legislation outlawing discrimination on the basis of HIV status in PNG (the HIV/AIDS Management and Prevention or HAMP Act, passed by the PNG Parliament in August 2003 and gazetted in 2004.) Enrolling as a graduate student at ANU with scholarship funding, Christine wanted to reflect on those experiences and to pursue a PhD which would contribute both to scholarship and positive social change in PNG. She early decided to focus on how introduced law had criminalised sexual relations between consenting adults—'prostitution' or 'sex work' and sex between men, or 'sodomy' in the archaic language of the introduced criminal law. She believed that the best place to pursue this research was in the capital, Port Moresby, eschewing advice that would have led her to more conventional ethnographic locales in remote rural settings. I strongly supported her in this decision and in the methodology she chose, combining a textual study of the adjudication of criminal cases of alleged 'prostitution' or 'sodomy' and confidential interviews and life histories with those who were selling sex and those who were engaging in male-male sexual relations. Early in her research she was outraged by the flagrant physical and sexual violence of a police raid on the Three Mile Guesthouse in 2004, the humiliations of the forced long march of many women, men and children to a distant police station, and their protracted time in custody without food or medical treatment. Her outrage fuelled a superb analysis of this infamous incident and the debates it generated in public media; this featured prominently in both her thesis writing and other publications. She pursued her archival and her ethnographic research in Port Moresby with gusto, aided by the generous assistance of many old and new friends and supportive individuals and organisations including Dame Carol Kidu, Fiona Hukula-Kenema, Josepha Namsu Kiris (formerly Kanawi) and all the staff of the Poro Sapot project of the NGO Save the Children. She conducted sensitive interviews with marginalised and stigmatised women, men and transgendered people with confidentiality and tact, documenting poignant stories of violence and humiliation. Equally impressive was her forensic analysis of court cases and the judicial perpetuation of discriminatory decisions, often perverting the intentions of law reformers to redress discrimination. She considered the force of the introduced criminal law and of Christianity in promoting ideals of heteronormative and monogamous marriage. She situated the violent discrimination she witnessed in the context of the HIV epidemic in PNG which led to those selling sex or having same-sex relations being unduly blamed for its spread. She interrogated the influence of ideals of 'human rights' and how these might become locally meaningful. She pondered the power of imported words and labels, such as 'sex work', suggesting that 'survival sex' was a more appropriate moniker in PNG. Her theoretical framing drew on broader social theories about knowledge and power (such as those of Michel Foucault) and a staunchly intersectional feminism which revealed the interaction of gender, sexual, race and class oppressions. Although much older than many of the PhD students who were part of our stellar ARC team in that period, Christine was extremely dedicated and energetic, and increasingly adept at using the latest software and bibliographic tools. During her candidature she wrote not only thesis chapters but several articles, chapters and conference papers. She published a prize-winning essay 'Men Behaving Badly', on the prohibition and punishment of 'sodomy' in the colonial period, in The Journal of Pacific History (2008). She initiated an important panel on gender violence at an international conference in Hawai'i. When the publication of papers from that event was distracting her unduly from her thesis writing I offered to assist. This led to our co-edited collection Engendering Violence in PNG (ANU E Press 2012), a volume in which Christine's own chapter on the Three Mile Guesthouse raid ('Crime to be a woman: Engendering Violence against Female Sex Workers in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea' is a compelling contribution.

In her review in The Journal of Pacific History, Michelle Rooney (2017) said:

In a review in this journal Tui Nicola Clery wrote:

Her book thus palpably fulfilled Christine's desire to make not just a scholarly contribution but one which offered policy and practical insights to redress discrimination against and promote justice for all of PNG's citizens. My conversations with her over the last hard years suggested that publication of her book was an immense solace and a source of pride and some peace. During her time as a PhD student Christine dealt with a number of major life challenges: in looking after her beloved aged father and dealing with his death, in the long-term maintenance and eventually the sale of her beautiful farm in the Bega Valley, in the logistics of her move to be with her old friend Keith Stebbins on Coochiemudlo Island near Brisbane and the transfer of most of her academic library to Divine Word University in PNG. And the chilling discovery, after only a short time in her new island home, that she was suffering from a debilitating and deadly disease. She was not to slip easily off the island into the embrace of a warm ocean as she had imagined and hoped. She may have first desired death but she lived on for years in Feros Village, set amongst rolling hills near Bangalow under the close care of staff there, with her family nearby. She remained feisty to the end, her body beleaguered but her mind astute and wit intact. Along with John Ballard and Katherine Lepani, I was honoured to be her academic supervisor but also her supporter and her friend. Her brother Steve and sister in law Hilary Wise gave much in nurturing her through this final phase in their familial life, along with many long-time faithful friends who, through visits to Bangalow, or through Skype, phone, texts and emails, sustained her and kept her company in her last days. |

|

Christine at her PhD graduation, ANU Canberra. © Prof Gil Herdt

Christine at her PhD graduation, ANU Canberra. © Prof Gil Herdt