From Soetji to Soendel:

Negotiating Race, Class and Gender in a Netherlands Indies Newspaper

Grace V.S. Chin and Tom Hoogervorst

Introduction

-

In the interwar years, new worlds opened up for young people across continents. They could—in much greater numbers than had previously been possible—obtain higher education, dress in the latest fashion, meet new people away from the watchful gaze of their parents, consume modern products, visit new places, go out on a date, smoke, drink and even dance. The increasingly globalised, visual and capitalistic world of the 1920s and 1930s became the stage of the iconic 'modern girl' and 'new woman.' [1] Fashionable, expressive, erotic, emancipatory and threatening, these trans-imperial archetypes of modern womanhood often proved a challenge to the disciplinary patriarchal forces of colonial and nationalistic elites alike. While modernity created new freedoms for men,[2] women—charged with the guardianship of cultural values and practices—faced persistent limitations, in particular with regard to entrenched notions of the female body and sexuality.

-

This article examines the contestations surrounding the modern or 'new' woman in the Netherlands Indies of the 1920s and 1930s, and how they inform the negotiations of complex ethnic, gender and class identities and relations within the colonial context. We draw from the opinion pieces and readers' letters published in Sin Po (1910–1965, Batavia/Jakarta), one of the most prominent Sino–Malay newspapers in the Netherlands Indies.[3] This media outlet was in the hands of the Indies-born, Malay-speaking Chinese community, known as the 'Peranakan Chinese' (henceforth Peranakan). Catering mostly to a China-oriented, middle-class, and Malay-literate readership, Sin Po provides first-hand insights into the confluence of historical events characterising early twentieth-century Southeast Asia, including the heated debates surrounding nascent Chinese nationalism and the revival of Confucianism,[4] the position of the Chinese in an increasingly anti-colonial political landscape, and the forces and perceived dangers of modernisation, which included the education and emancipation of local women. As many of these discussions challenged the very institution of European colonialism, most journalists working for Sin Po wrote under pseudonyms, especially when it involved voicing their grievances and opinions in the widely read newspaper.

-

To supplement their meagre income, many journalists took to publishing fiction and often rehashed the same material in their novels and short stories, be it the sensationalised news of the day[5] or their own opinions on the trending issues that gripped the society. As a result, the line between reality and fiction sometimes blurred as journalists fought their battles using the literary and media landscapes; this is especially true with opinion pieces, many of which masqueraded as fiction. In telling a complementary story about the Peranakan woman, the majority of Sino–Malay novels, short stories, and newspapers reflected a deeply parochial and chauvinistic way of thinking, even if male journalists and authors sometimes wrote under feminine pseudonyms to trick the readers into thinking they were entrusted with an occasional female perspective.[6] By the 1920s, the popular mediums of the press and literature invariably became new, and powerful, social forms of disciplining wayward women through the threat of public exposure and shaming.[7] Nowhere is this clearer than when the spotlight was turned onto the 'problem' of the emancipated, western-educated Peranakan woman, whose modernising behaviour captured the imagination of writers/journalists and readers alike.

-

Much attention has been given to the link between socio-cultural transitions and the changes in Peranakan femininities of the early 1900s Netherlands Indies,[8] with studies focusing on Sino–Malay literature,[9] women's journals,[10] and Agony Aunt columns.[11] Helpful as these publications are in enriching our understanding of the discursive forces that shaped the modern woman, we need to move to the opinion pieces and readers' letters for a stronger picture of the internal discussions and tangible concerns on societal change and its cultural impacts. This still largely untapped resource featured some of the most vocal debates on the role and identity of the Peranakan woman, and can provide invaluable insights into the normative perceptions and attitudes toward gender identities and relations of the day. More often than not, these opinion pieces and letters functioned as a propaganda diatribe and carried skewed, misogynistic viewpoints that attacked the modern Peranakan woman for being dangerously enamoured with the West and all things western.[12] Colonialism added to this discourse a dimension in which modernisation was inextricably linked to westernisation. This perception was so widespread in the Netherlands Indies that it prompted the counter-discourse of gila Barat (obsessed with the West), a trope often used in (Sino–) Malay writings to denounce the contaminating influence of the West.[13] As we will see, this discourse features prominently in Sino–Malay opinion pieces and letters on women and modernity.

-

Made from a Sino-centric, male standpoint, the criticisms contained in the opinion pieces and letters underlined the anxieties and frustrations of a threatened masculine ego. The writers' tones and attitudes, ranging from anger, disdain and contempt to bewilderment and ambivalence, leave little to the imagination as to how they viewed the modernising Peranakan woman and her transgressive body and sexuality. Left uncontained, she could potentially disrupt the domestic ideologies of wifehood and motherhood—the cornerstone of their patrilineal-patriarchal family institution—as well as the normative gender binary that confined Peranakan masculinities and femininities within their ordained roles and spaces.[14] Unsurprisingly, the arguments and perspectives presented in the opinion pieces and letters are very much coloured by simplistic, patriarchal understandings of purity and pollution as a cultural concept,[15] through which the polarisation of stereotyped femininities is established: virgin/purity versus whore/pollution. This polemic is then produced as a truism and helps demarcate two distinct femininities: those who conform to traditional roles and those who transgress them.

-

We thus structure our article according to the line of thinking articulated in the opinion pieces and letters, in which the sexual gradation (and degradation) of women is seen in the rhetorical trajectory from soetji (virgin, pure) to soendel (whore, immodest). Doing so enables us to also trace the contradictions and disjunctions that make up the psychology of the China-oriented, middle-class Peranakan male. These moments of ambivalence and tension are significant to our analysis, as they disclose the thorny relations and negotiations of race, class and gender wrought about by centuries of colonial rule. This can be seen whenever the narrative shifts to the soendel figure, which is implicitly related to the emancipated western woman. Simultaneously desired and rejected, the soendel figure in social and popular imaginaries is singled out by an angry Peranakan male orthodoxy as the tainted product of the West—whether she is a westernised Peranakan woman or a western woman. Paradoxically, these patriarchal frustrations and fears were never directly aimed at the western white man.

-

The intersections of race, class and gender explored here reveal subjective and psychological complexities that cannot solely be explained by patriarchal domination and discrimination. While we recognise the profound misogyny and sexual hypocrisies at work in the opinion pieces and letters, we also contend that Dutch imperialism has complicated the reasoning for the Peranakan patriarchal reaction against transgressive femininities. The endemic and systematic racism and sexism that underpinned colonialism cannot be ignored, as both phenomena are historically imbricated in the construction of the (Peranakan) Chinese as marginalised and displaced 'Other' within the institutionalised hierarchies of race, class and gender. To understand the psychological consequences of imperialist domination on the Peranakan patriarchal community and, correspondingly, the modern Peranakan woman, we address the following: What is the line of thinking of the journalists and readers who aired their views in Sin Po, and how is it propagated in their opinion pieces and letters? What kind of social or cultural anxieties are reflected in their written work? And in what ways did colonial relations of race and class influence 'local' negotiations of gender identities and relations? We now turn to the analysis to consider these questions.

From soetji to soendel

-

Before the forces of modernisation had taken root in the early decades of the twentieth century, the lives of Peranakan women were sharply circumscribed by home and family and, despite their acculturated status in the Netherlands Indies, they still subscribed in part to Confucian-gendered doctrines, the most important of which was the preservation of chastity before marriage and the maintenance of virtue after it.[16] According to Margaret Bocquet-Siek, the Peranakan emphasis on female chastity had come 'close to becoming a cult';[17] it was a badge of her sexual and bodily purity, a desirable commodity that could secure a good marriage and elevate a family's social standing. The chaste female body was prized as it could safeguard the continued 'purity' of the patrilineal bloodline and name by birthing the desired son. To this end, the daughters of affluent families would enter seclusion (pingitan) after their first menstruation; they were confined to their homes in order to avoid the polluted outside world where male strangers posed a sexual threat and danger to them and their families.[18] The most common term to denote this state of unpolluted femininity is soetji, which carries connotations of purity, innocence, chastity and virginity. In this regard, the more privileged Peranakan woman often led a more secluded life compared to those from the lower economic classes.[19] The cultural notion of soetji therefore played a key role in regulating the female body and became a normative repertoire that could be drawn from to impose ideals of correct gender behaviour. It also captured a romanticised 'pure' Chinese, traditional past, with which these untainted women were associated, and which had to be protected from the encroaching foreign influences to prevent the deterioration of the Peranakan culture and women alike.[20]

-

At the turn of the twentieth century however, traditional femininities began to change with the educational opportunities offered from 1903 onwards by the Chinese-language Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (Chinese Association) schools for girls, and from 1908 onwards by the Dutch-language co-ed Hollandsche-Chineesche School.[21] Old-fashioned traditions like arranged marriage were increasingly challenged by the youth of this era, while the idealisation of romantic love or 'pure love' (tjinta soetji) entered the popular imaginary through published literature on the theme. The promise of social progress (kemadjoean) offered by western modernity was a seductive one; a growing number of Peranakan men embraced it by expressing their wish for a self-chosen wife, preferably one educated enough to complement their own modernity, help educate their children, and bring up the 'modern' Peranakan family. Still, the extent to which a modern Peranakan woman could adopt western ways was subject to strict limits. Picking the fruits of modernity was encouraged as long as her role and place remained bound to domesticity, but any type of behaviour that fell outside the purview of traditional femininities, or deemed antithetical to the established gender norms was invariably censured as tjemar (polluted) and subjected to the disciplinary forces of culture and society.[22] The imaginary line between desirable and undesirable forms of modernity is thus fully consistent with gender distinctions and performativity; while it was acceptable, even attractive, for men to flaunt their westernised ways through the use of European languages, clothes, and other visual signifiers that marked their modern self-identification,[23] it was considerably less so for women who sought to do the same.

-

It is relevant to note here that numerous Sino–Malay journalists and authors were quick to identify western education as a main cause of the purported decline in morality among Peranakan women.[24] In the opinion pieces and letters submitted to Sin Po and other newspapers, a brief word of praise to the benefits of European education was typically followed by a diatribe about the ways it imperilled their women through moral and sexual corruption. Not only was it said to expose girls to (liberal) ideas deemed unsuitable for Eastern values (ketimoeran), but the very thought of socialisation between the genders was greeted with anxiety and condemnation. As a result, European education presented a paradox: while desirable as a civilising force, it was feared in equal measure on account of its perceived dangers to female propriety and culturally embedded notions of decency and chastity. Moreover, since access to Dutch schools was in part income related,[25] the modernising Peranakan girls deemed a threat to traditional values predominantly belonged to the upper classes. Class and western education were so firmly linked that they resulted in a commonly featured narrative plot in which a young 'modern' girl, often depicted as a rich man's daughter, has been spoilt by excessive freedom. Labelled keblanda-blandaan (Dutchified),[26] this archetypical affluent, westernised girl features in numerous Sino–Malay novels and short stories.[27] Characterised as being too free and 'noisy' (riboet), she usually possesses unappealing habits, including snobbery by sporting a western name, speaking in Dutch, having non-marital relationships with men, and dancing with men 'of all ethnicities and qualities' (dari segala bangsa dan segala qualiteit).[28] Even if class is not explicitly brought in, it is nevertheless implied through the modern girl's 'up-market' leisurely activities and time spent in pursuit of the latest western fashion, dating and dancing. While race and gender are crucial to the debates at hand, the tacit knowledge of the modern girl's moneyed background should also be kept in mind in the following analysis.

-

In 'Gadis-gadis Tionghoa' (see Figure 1),[29] the anonymous writer makes a case for the corrosive influence of the West on the perceived purity of Peranakan women by contrasting women of the past to those of the present. By using the words gadis-gadis and siotjia-siotjia (girls) rather than prampoean-prampoean or hoedjin-hoedjin (women), the writer establishes his own higher position in terms of both gender and age while emphasising the girls' immaturity and vulnerable purity. According to the patriarchal logic of this piece, Peranakan 'girls' need an older, masculine, and moral voice to guide them through the changing times and 'watch out' for the dangers of modernity, expressly defined here as 'freedom':

Nowadays Chinese girls in the Indies are also changing. In the past, when girls reached maturity, they were quickly locked away inside the house until candidates could be found to become their husbands; now girls have more freedom … But in granting them more freedom, people should also recognise boundaries, so that Chinese girls will not imitate the example of their white-skinned siblings too much and likewise engage in the freedom to dance, flirt and suchlike. One has to watch out for this!

Figure 1. On the right, the Sin Po piece 'Gadis-gadis Tionghoa.' On the left, a sexualised advertisement for fragrant oil (minjak wangi), which shows that the editors' moral concerns were often mitigated by considerations of a more capitalistic nature (vol. 148 (1926): 689).

-

Here, the writer reminds his readers to be mindful of the ideological boundaries that separate their 'authentic' Peranakan world from the imitative posturing brought about by westernisation and the polluting effects of gila Barat—being obsessed with the West—as a discourse. Less obvious, though just as important, is the fact that the writer is equally critical of the 'white-skinned siblings' whose morally reprehensible behaviour, 'dance, flirt and suchlike,' is leading the pure, innocent Chinese girls astray. There is more than just gender-related conservatism at work here, as the implicit racism in this statement also reveals the construction of a culturally superior Chinese and/or Peranakan self, through which an anti-colonial stance is made.

-

Time and again, the theme of 'purity in peril' resurfaces in the opinion pieces and letters published in Sin Po. The writers of these pieces repeatedly attacked what they considered intolerable female behaviour, the worst of which were flirting and dancing, since they brought women into close, even intimate, proximity with unacquainted and worse still, foreign, men. At the same time, the writers also challenged—whether openly or tacitly—the imperialistic, white, Western world for being the cause of their social and cultural woes:

What white people call 'flirt' or 'flirtage'—which means unconstrained coquetry between all women and all men—was previously unknown among our people. Because, according to Chinese tradition, a Chinese woman is only a woman for her husband and not a single genuine Chinese woman would even think of fooling around with other men … So be careful, Chinese people, and do not bring ruin upon yourself with the coquetry of foreign people, which people mistakenly call 'freedom' or 'civilisation.'[30]

-

In the excerpt above, taken from 'Adat-istiadat dalem perkara tjinta,'[31] the pervasive, moralising voice cautions against the dangers of flirting through the imagined boundary that separates the naïvely innocent Peranakan community from the knowledgeable West, and 'genuine' feminine behaviour from inauthentic imitations. Here however, the coloniser/colonised binary is further problematised by the local perception that certain forms of knowledge bring corruption rather than enlightenment. The knowledge of western, emancipated female conduct is notably portrayed as a forbidden fruit for the pure, virtuous Asian woman, one that could precipitate their sexual downfall and bring ruin to their cultural 'Eden.'

-

The fear of excessive western freedom and its detrimental effects on Peranakan women was particularly felt in the domain of modern dancing (dansa). According to the conservatives of the time, western dances were just one step away from prostitution. While the more respectable waltz, polka and quadrille were still acceptable in the eyes of some, the tango and foxtrot were invariably dismissed as mesoem (obscene) or tjaboel (lascivious) as they engendered bodily contact: 'And during grand dance parties [women's bodies] are not just shown and demonstrated, they are rubbed and polished against the bodies of men.'[32] Ironically, the horrified authorial voice in the above opinion piece reveals a prurient fascination with the sexual albeit tainted female body, a popular motif that thrived in the fervid patriarchal imaginings of Peranakan girls gone bad. As these 'grand parties' were usually attended by girls from a privileged socio-economic background, the criticism also indirectly targeted the wealthy Peranakan families for giving their daughters excessive freedom. Outsiders (Europeans) were also implicitly blamed for this deplorable state of affairs, but—as we will see later—the finger was rarely pointed directly at the white, European men at the top of the colonial hierarchy. While dancing with strangers was already bad enough, dancing or socialising with men from other ethnicities—especially Eurasian (Indo or sinjo) playboys—was perceived as an outright threat not only to innocent Peranakan girls,[33] but also to the imagined purity of the Peranakan race and ethnicity.

-

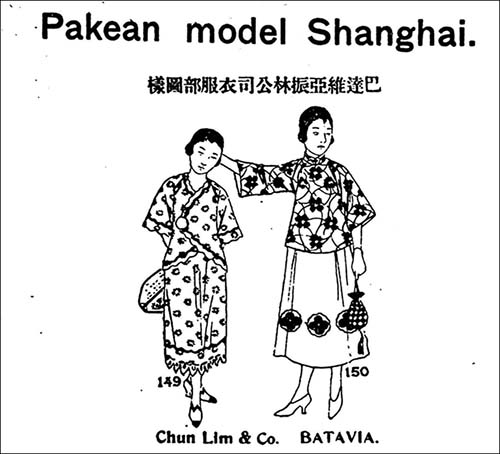

Another sexual danger explicitly linked to dancing was the exposure of the female body, as women were expected to wear the latest, and relatively revealing, western fashion to attend dancing parties. Indeed, it was common for the (predominantly male) authors of Sin Po and other newspapers to accuse Peranakan girls of dancing while being half naked (separo terlandjang). For the same reason, they were also among the most fervent critics of 'mixed bathing' (mandi tjampoeran), a new-fangled habit taking place at the swimming pools of large cities. Opinion pieces on western dancing often concluded with a plea to stamp out the habit entirely, sometimes by alluding to similar situations in other Eastern countries. One author, for instance, considered Japan's outlawing of western dance as a liberating example worthy of imitation across Asia.[34] Another author warns his readers that the introduction of dancing in Shanghai had led to the destruction of Chinese culture in that city, and even resulted in its subjugation by foreign powers.[35] It was not uncommon for authors to look to China for the proper sartorial role models and in doing so reinforce the anti-colonial rhetoric of a traditional, moral East resisting a modern, immoral West. A short, anonymous article titled 'Selaloe Bedah' exemplifies this prevalent viewpoint: 'In China, women who are barely dressed belong to the lowest classes, yes, even Chinese whores wouldn't dare to dress half-naked. But in the West it's actually women from the 'high' classes who most enjoy revealing their bodies, so that almost everything is exposed' (Figure 2).[36]

Figure 2. Advertisement, seen on the first page of various 1924 volumes of Sin Po, on the latest fashion from Shanghai. The Malay text translates as 'Shanghai-style Clothing' and the Chinese text as 'Chun Lim Company Batavia, Clothing Department Samples.'

-

Significantly, the above extract underscores a shift in Chinese-oriented, patriarchal thinking, as it turned from the transgressive Peranakan girl to the emancipated upper-class western woman as a scapegoat for their frustration, anger and anxieties. At the same time, the intertwined structures of race, gender and class are reflected in the condemnation of western immorality. Unlike in the previous extracts, the western woman is identified here as the main polluting factor due to her propensity for indecent exposure, and thus she is judged as morally 'lower' than Chinese prostitutes. Although the writer falls one step short of calling the western woman a prostitute, the author of 'Pakean Sopan' has no such qualms: 'Western fashion tends to emerge from the brains of prostitutes from the big cities in the West, so that it shouldn't surprise anyone that these clothes—exposing the chest, neck, armpits, and thighs—clearly show the nature of the people who 'create' this highly refined fashion.'[37]

-

Reminiscent of Victorian England's gender polemics of the angel and the fallen woman, the well-established soendel figure in Sino–Malay literature and press often served as a disciplinary trope for the transgressive or unrestrained female body and sexuality.[38] Cross-culturally, the prostitute figure in patriarchal imagination is often the subject of both fear and desire. Not only can this seductive archetype destroy a man's morality, her disease-riddled body poses a danger, both physical and metaphorical, to men and to society. Analogies between moral filth and physical contamination are commonplace in many cultures. In the Sino–Malay vocabulary, sexually transmittable diseases were labelled 'woman's diseases' (penjakit prampoean) or 'filthy diseases' (penjakit kotor), an association that compares the female body to filth. And, as stressed by yet another anonymous writer, the West too holds the female body responsible as the carrier of sexual diseases, since the European term 'venereal' is derived from 'Venus.'[39]

-

Sinful, infectious, filthy and polluted, the soendel and other names for prostitutes became swearwords to invalidate people and practices deemed morally objectionable or unmanly.[40] In Sino–Malay literature of the early 1900s, the soendel trope was heavily associated with revealing (western) clothes, flirting, dating, and other 'shameful' activities that involved being seen by men or socialising with them. However, while the labelling of soendel was often directed at the western-educated, freedom-loving, modern (and often well-to-do) Peranakan 'girls', it was more precisely embodied by the western woman who was viewed as a terrible influence on weak-minded Asian girls and, therefore, the 'real' danger. As another writer argued, western emancipation (represented by the 'New' or 'Modern' Woman in Europe) was the major reason behind the decreasing marriage rates observed among women in the late 1920s Netherlands Indies.[41] The following excerpt from an article titled 'Samingkin lama samingkin edan' also speaks volumes on the subject of the 'white woman' (prampoean poeti):

If one was to say that [white women] keep up with fashion to flirt around and attract the attention of random men on the street, much like the behaviour of a prostitute, they would definitely get very angry and protest … But now they provide the evidence themselves; by having to 'decorate' their naked body, they themselves indicate that they really want random men to look at their flesh; that this is really what they want. We just hope that this kind of 'civilisation' will not spread to the East.[42]

-

Likened to a contagion that could 'spread to the East,' the diseased body of the western woman is held up as a cautionary tale symbolising all the things that a pure and proper Peranakan woman should never be or do. This warning is seen in the article 'Pergaoelan lelaki dan prampoean,'[43] which contrasts the proper Chinese girl and her strong Eastern morals with the degenerate western woman who goes out with male 'friends' and dances until the roosters crow: 'Before she gets married a Western girl has generally had her fill of fooling around, her fill of rubbing her body against tens if not hundreds of men (while dancing!), so that it's difficult to still consider her as truly pure.'[44] Much of their purity will disappear as a result of dancing, the writer argues by comparing western women to flowers that eventually lose their fragrance as a result of being passed from hand to hand. As with the earlier viewpoints, the writer here too conveys a grave warning to the Peranakan public, especially its modern girls, of the consequences of appropriating western freedom, represented here as the western woman's sinful ways and fouled body. Even more significant is the link made between western culture and female impurity, for it underscores the complex intersections and negotiations of gender, class, and race within the colonial context.

-

According to Susan Abeyasekere, nineteenth-century Javanese society widely subscribed to the notion that women were the 'natural' transmitters of culture.[45] This popular perception is also found in the Sino–Malay literature and press of the early 1900s, in which the pure woman (prampoean soetji) embodied the inviolability of cultural values and traditions. The corporeal margins of the female body were symbolic of the ideological integrity and sanctity of the Peranakan as a community; however, only men could be its moral gatekeepers and guardians, the 'protectors' and 'defenders' of their women (perceived as naturally weak), culture and ethnicity. It is also due to this implicit understanding that many male journalists and authors undertook the role as the authoritative voice of morality. By extension then, the figure of the western or westernised soendel—as the metaphorical transmitter of (immoral) western values—is also representative of the contaminated, and thus weakened, foundations of the European empire and civilisation. Pivotal to the widespread anti-colonial sentiments of the Peranakan and their defensive discourse of gila Barat, the frequent allusions in Sin Po and other Sino–Malay newspapers to the cultural inferiority of the western world would have undermined the idea of the colonial Dutchman as a figure of unquestionable authority.

-

Yet, for all the subversive elements in their opinion pieces and letters, the anonymous writers were also careful not to implicate the white man in their indictments of western immorality. As a matter of fact, several of their articles invoked European male authorities to show that mixed-gender activities like flirting and dancing were also negatively perceived in Europe.[46] The writer of the piece 'Orang Barat tentang dansa' cites no less than two dozen European authors to support his case that dancing is uncivilised and, worse, part of a whorish (soendel) culture (Figure 3). In other words, the transgressive, polluting element that is the emancipated western woman has been judged as the one truly at fault here, and similarly criticised by the western patriarchal order. Of significance too is the writers' dependence on the 'superior' western masculine logic to support their misogynistic views, for it exposes not only the colonial binds between master and subject, but also the self-contradictions inherent in the Peranakan writers' position when it came to the issues of gender and modernity. Encoded with the meanings, values and perceptions of its time, the opinion pieces and letters analysed above—and the gendered and racialised critiques of feminine performativity contained within—tap into the subjective and psychological disjunctions of a subordinated (and feminised) Peranakan patriarchy whose colonised mentality had been shaped by the centuries-long subjection to the imperialist dictum of European, masculine ascendancy.

Figure 3. First page of the Sin Po article 'Orang Barat tentang Dansa' (Westerners on the subject of dance) (vol. 306 (1929): n.p.)

Conclusion

-

Our analysis of Sin Po illustrates how the Sino–Malay newspapers of the late-colonial Netherlands Indies served as a battleground for gender issues, in which the debates of the day were heavily influenced by China-oriented, patriarchal opinions and sentiments about the modern Peranakan woman. As the newspapers' owners and editors implicitly sanctioned the opinion pieces and letters they published, this also meant that the press was complicit in the sexist reproduction and circulation of misogyny as a public discourse through the dichotomous portrayal of women as either pure virgins or polluted whores. Although their articles had constructed a skewed image of women and reality, we find that the writers also projected their own anxieties, fears and desires onto the female body and sexuality, as seen in their rhetorical trajectory from soetji to soendel. In doing so, they perpetuated two popular stereotypes that came to define notions of gender in the society. On one end of the spectrum was the Chinese woman, who represented tradition, decency, modesty and family values. On the other, was the western woman, who was modern in all senses: educated, fashionably dressed, but also 'loose' and uncontrollable, and therefore a threat to both local and western patriarchal ideals of proper femininity. The Chinese woman who aped the emancipated ways of the western woman was likewise guilty, but only to a degree, since she was also perceived as a victim of the western woman's bad influence. Although the tensions we have highlighted between the Peranakan man and the western woman point to the workings of a deep-seated racism and sexism, the issue is further complicated by the historical subjugation and marginalisation of the (Peranakan) Chinese as racialised 'Other.' The writers' complicit silence on the culpability of the modern western man, familiar to them as the figure of the Dutch male coloniser, also suggests that the Peranakan patriarchy had in part internalised their own emasculated position in the colony as the subordinated, racialised and gendered 'Other.' In the end, their writings on the modern Peranakan woman reveal themselves to be much more than simple opinion pieces or letters, for they reflect how bigotry and power are enmeshed in the production and negotiation of race, class and gender within the context of Dutch colonialism.

Acknowledgements

Grace V.S. Chin is thankful to the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV) in Leiden for the award of senior fellowship. Tom Hoogervorst appreciatively acknowledges financial support from the Dutch Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) as part of its Innovative Research incentive ('Vernieuwingsimpuls').

Notes

[1] See Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong and Tani E. Barlow (eds),The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity and Globalization (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008). On the modern girl in late-colonial Penang, Malaya, see Su Lin Lewis, 'Cosmopolitanism and the modern girl: A cross-cultural discourse in 1930s Penang,' in Modern Asian Studies 43(6) 2008: 1385–419. On the 'New Woman' in pre-war Japan, read Kazumi Ishii, 'Josei: A magazine for the "New Woman",' in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 11 (August, 2005) and Jan Bardsley, 'The New Woman meets the Geisha: The politics of pleasure in 1910s Japan,' in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 29 (May, 2012).

[2] Tom Hoogervorst, 'Manliness in Sino-Malay publications in the Netherlands Indies,' in South East Asia Research 24(2) (2016): 283–307, pp. 296–300.

[3] See Charles A. Coppel, Studying Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia (Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 2002), 55, on the political ideology and social importance of Sin Po. The choice for this newspaper has in part been pragmatic; many of its issues have been digitised by KITLV Leiden and the Leiden University Library plans to make them available in the near future. See also Ahmat B. Adam's The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness 1855–1913 (Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1995), especially Chapter 4 (58–78) on the rise of the Chinese vernacular press.

[4] Leo Suryadinata, Peranakan Chinese Politics in Java: 1917–1942 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1981).

[5] Elizabeth Chandra, 'Women and modernity: Reading the femme fatale in early twentieth-century Indies novels,' in Indonesia 92 (October, 2011): 157–82, pp.158–61.

[6] Elizabeth Chandra, 'Blossoming Dahlia: Chinese women novelists in colonial Indonesia,' in Southeast Asian Studies 4(3) (December, 2015): 533–64, p. 539.

[7] As an example, read Tineke Hellwig, 'Hermine Tan: A Western-educated Chinese girl,' in Women and Malay Voices: Undercurrent Murmurings in Indonesia's Colonial Past, Tineke Hellwig (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2012), 127–50.

[8] Margaret Bocquet-Siek, 'The Peranakan Chinese woman at a crossroad,' in Women's Work and Women's Roles: Economics and Everyday Life in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, ed. Lenore Manderson (Canberra: The Australian National University, 1983), 31–52; Myra Sidharta, 'The making of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' in Indonesian Women in Focus: Past and Present Notions, ed. Elsbeth Locher-Scholten and Anke Niefhof (Leiden: KITLV Press, 1992), 58–76; Charles Coppel, 'Emancipation of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' in Women Creating Indonesia: The First Fifty Years, ed. Jean Gelman Taylor (Melbourne: Monash Asia Institute, 1997), 22–51; Hellwig, Women and Malay Voices, 127–79; Chandra, 'Women and modernity,' 157–82, and 'Blossoming Dahlia,' 533–64.

[9] For a more comprehensive list of studies on the subject, please refer to Chandra, 'Blossoming Dahlia,' 534.

[10] Faye Yik-Wei Chan, 'Chinese women's emancipation as reflected in two Peranakan journals (c. 1927–1942),' in Archipel 49 (1995): 45–62.

[11] Christine Pitt, 'The agony of love: A study of Peranakan Chinese courtship and marriage,' in Chinese Indonesians: Remembering, Distorting, Forgetting, ed. Tim Lindsey and Helen Pausacker (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), 165–84.

[12] More progressive-minded male writers represented a minority. The famous and prolific Peranakan writer Kwee Tek Hoay (1886–1951), for example, contributed to the advancement of gender and other social issues in the media; his daughter later followed his footsteps. Read Sidharta, 'The making of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' 71.

[13] Other terms include kemaboekan Barat (intoxicated with the West), gila kedjoe (obsessed with cheese), baoe mentaga (smelling of butter), and memboeroe pada Kebaratan dengen memboeta (blindly chasing all things western). A similar discourse existed among the non-Chinese Indonesians, see Doris Jedamski, 'Mabuk modern and gila barat – Progress, modernity, and imagination: Literary images of city life in colonial Indonesia,' in Lasting Fascinations: Essays on Indonesia and the Southwest Pacific to honour Bob Hering, ed. Harry A. Poeze and Antoinette Liem (Stein: Yayasan Soekarno, 1998), 167–85.

[14] This binary is based on localised discourses and practices of complementary male-female relations that define family and social order. These so-called 'complementary' identities were produced through the marginalisation of women within the male-inscribed hierarchies of the Peranakan culture, even if they had relatively more autonomy and freedom than mainland Chinese women due to the predominance of their involvement in the economic life through trade and small home- and family-oriented businesses (Bocquet-Siek, 'The Peranakan Chinese woman at a crossroad,' 39). However, the oft-clichéd high status of women in Java and elsewhere in Southeast Asia has recently been questioned by Akiko Sugiyama, 'Ideas about the family, colonialism and nationalism in Javanese society, 1900–1945' (PhD diss., University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, 2007).

[15] See Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1966). She argues that many traditional societies invest the individual body and its margins with symbolic and emotional significance according to notions of purity and pollution.

[16] The obsession with woman's purity differentiated the Peranakan woman from the indigenous woman as the latter generally exhibited a more relaxed attitude toward marriage, divorce, and remarriage. As a result, the indigenous woman was occasionally depicted as loose and untrustworthy in both Sino –Malay and Dutch literature.

[17] Bocquet-Siek, 'The Peranakan Chinese woman at a crossroad,' 41.

[18] For an insight as to what pingitan entails, read Raden Adjeng Kartini, Kartini: The Complete Writings, 1898 –1904, ed. and trans. Joost Coté (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2014), 69. A member of the Javanese aristocracy (priyayi), Kartini eloquently describes how she suffered this practice. In Sino–Malay texts, one also encounters the near-synonym terkoeroeng or 'locked up.'

[19] To a degree, young women from the lower classes were still expected to conform to the ideal of soetji, though perhaps not as rigidly as the women from better socio-economic backgrounds.

[20] See Grace V.S. Chin, 'Female virtue and Chinese nationalism in the Sino-Malay literature of the Dutch Indies,' unpublished ms., 2016. Her article examines how female virtue and purity in Sino–Malay literature are tied to the racial and cultural constructions of Tionghoa (Chinese) among the Peranakan in their desire for nationhood in colonial Java.

[21] Bocquet-Siek, 'The Peranakan Chinese woman at a crossroad,' 42–45.

[22] We can see these forces at work in early twentieth-century male-authored Sino–Malay fiction, in which transgressive female characters were commonly 'punished' by suffering and death. Often, these novels opened with a disclaimer explicitly stating why they were written and what lessons their imagined readership was supposed to learn from them. Refer to Chandra, 'Blossoming Dahlia,' 533.

[23] Hoogervorst, 'Manliness in Sino-Malay publications in the Netherlands Indies,' 296–300.

[24] Sidharta, 'The making of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' 69–71.

[25] On education and the (Peranakan) Chinese in the late-colonial Netherlands Indies, see Margaret Bocquet-Siek, 'Modern education and Peranakan Chinese society in Java: Some aspects of the relationship between modern education and social change among Peranakan Chinese elites in early twentieth century Java' (PhD diss., Griffith University, 1984); and Ming Tien Nio Govaars-Tjia, Dutch Colonial Education: The Chinese Experience in Indonesia, 1900 – 1942 (Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre, 2005).

[26] John B. Kwee, 'Chinese Malay literature of the Peranakan Chinese in Indonesia 1880–1942,' (PhD diss., University of Auckland, 1978), 160.

[27] Examples include Tjermin's The Secret of a Wealthy Girl or the Behavior of Nona Tan, a Highly Educated Chinese Girl in Weltevreden who Secretly Ended up Pregnant as a Result of her Freedom as was the Gossip of the Year of 1917 (Buitenzorg: The Teng Hoeij, 1918); K.Kh. Liong's two-volume novel The Story of Miss Tan Seng Nio alias Hermine Tan or How Parents should Educate their Children. A Story that Really Happened in Bandung from the year 1912 until the year 1917 (1918); and Liem Hian Bing's novel Valentine Chan or the Secret of Semarang (Semarang: Boekhandel Patkwah, 1926), while examples of short stories include Ang Jan San's Satoe Gadis Modern (A Modern Girl), Sin Po 59 (1924): 103–105; and 'Sie Pok Say,' Sin Po, 294 (1928): 527–28 written under the pseudonym Miss Tjay Po. Generally in such writings, modernity is associated with class, capitalism, consumerism, and the awareness of the latest western trends.

[28] Miss Tjay Po, 'Sie Pok Say,' 528.

[29] 'Gadis-gadis Tionghoa' (Chinese Girls), Sin Po, 148 (1926): 689.

[30] 'Adat-istiadat dalem perkara tjinta' (Customs and traditions in matters of love), Sin Po 13 (1923): 202–203.

[31] 'Adat-istiadat dalem perkara tjinta' (Customs and traditions in matters of love), Sin Po 13 (1923): 202–203.

[32] 'Kagenitan Barat' (Western coquetry), Sin Po 151 (1926): 751.

[33] See Coppel, 'Emancipation of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' 38–40; and Chin, 'Female virtue and Chinese nationalism in the Sino-Malay literature of the Dutch Indies,' 14–19. Both discuss how dancing with a Sinjo is explicitly linked to the loss of virginity in Liem Hian Bing's novel, Valentine Chan or the Secret of Semarang (1926). See also Sidharta, 'The making of the Indonesian Chinese woman,' 71.

[34] 'Basmi dansa mesoem' (Wipe out filthy dancing), Sin Po 168 (1926): 10015.

[35] 'Orang Barat tentang dansa' (Westerners on the subject of dance), Sin Po 306 (1929).

[36] 'Selaloe Bedah' (Entirely different), Sin Po 163 (1926): 939–40.

[37] 'Pakean Sopan' (Civilised clothing), Sin Po 303 (1929): 67–72.

[38] 'Bad' women in Sino-Malay literature sometimes become actual prostitutes after their evil plans fail. As an example, read Tan Chieng Lan's novel Oh Papa! (Surabaya: Hahn and Co., 1929).

[39] 'Polygamie dan pelatjoeran' (Polygamy and prostitution), Hoakiao 155 (1930): 11–14.

[40] Hoogervorst, 'Manliness in Sino-Malay publications in the Netherlands Indies,' 292.

[41] See, for example, the anonymously written article, 'Kenapa banjak prampoean tida kawin?' (Why do many women not marry?), Sin Po 291 (1928): 471–74. Note that in the contemporaneous European discourse, too, white women were typically blamed for "bringing ruin to the Empire," on which see Christine Doran, 'White women in colonial contexts: Villains, victims and/or vitiators of imperialism?,' in Lasting Fascinations: Essays on Indonesia and the Southwest Pacific to honour Bob Hering, ed. Harry A. Poeze and Antoinette Liem (Stein: Yayasan Soekarno, 1998), 99–115.

[42] 'Samingkin lama samingkin edan' (The longer the crazier), Sin Po 160 (1926): 896.

[43] 'Pergaoelan lelaki dan prampoean' (Socialisation between men and women), Sin Po 73 (1924): 337–38.

[44] 'Pergaoelan lelaki dan prampoean' (Socialisation between men and women), Sin Po 73 (1924): 337–38.

[45] Susan Abeyasekere, 'Women as cultural intermediaries in nineteenth-century Batavia,' in Women's Work and Women's Roles: Economics and Everyday Life in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, ed. Lenore Manderson (Canberra: The Australian National University, 1983), 15–29.

[46] For example, the text 'Orang Barat tentang dansa' (Westerners on the subject of dance) cites Auguste-Henri Forel and Havelock Ellis as examples of European experts who oppose dancing. On Auguste-Henri Forel, see Anton Leist (ed.), Auguste Forel: Eugenik und Erinnerungskultur (Auguste Forel: Eugenics and Cultures of Remembrance) (Zürich: vdf Hochschulverlag, 2006). On Havelock Ellis, see Phyllis Grosskurth, Havelock Ellis: A Biography (London: Allen Lane, 1980).

|