The New Woman Meets the Geisha:

The Politics of Pleasure in 1910s Japan

Jan Bardsley

Figure 1. 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara (Yoshiwara tōrō),' Tokyo Puck, 1 August 1912.

-

The Tokyo Puck comic, 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' captures a curious historical moment during the summer of 1912 when a small group of New Women known as the Bluestockings ignited public scandal by visiting a teahouse in the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters. The comic offers a way for us to understand how differently the Bluestockings (Seitō-sha, 1911–16) and geisha were viewed, and why some might find the idea of the two groups meeting absurd. In fact, the incident provoked more outrage than laughter. For three days after the story was published in the newspaper, people passing by the most famous Bluestockings' family home threw stones day and night. Certainly, for the Bluestockings, the moment was a rude awakening to the borders of gender, sexuality and class, but it was no doubt a reminder to geisha, too, of their marginalised and circumscribed place in Japan. We can also see this moment as representing a lost opportunity for connection between the two groups of women, and a point at which the boundaries dividing them from proper ladies were reinvigorated. When the Bluestockings defied convention by visiting a geisha house of their own accord, it was the last straw—something had to be done to protect the lady, and much less visibly, the privileges of men to have a wife and a geisha lover, too. This article develops these arguments by untangling the various strands represented in this comic—the status of geisha and teahouses, public perceptions of the Bluestockings and theirs of the geisha, and the activities of another group, the ladies of reform associations, who though absent from the picture, claimed a powerful presence in this narrative, inciting dissent from both geisha and Bluestockings.

Pleasure and protest: movements to abolish prostitution

-

The context of the reform movements of this era explains why the Bluestockings' visit as well as their writing on sexuality struck such a nerve. In the 1910s, groups in Japan such as the Japan Women's Christian Temperance Union (JWCTU; Fujin Kyōfūkai), the Salvation Army (Kyūseigun), and the newly formed men's Purity Society (Kakuseikai), were actively involved in a movement to abolish prostitution.[1] They perceived geisha and prostitutes as shameful women in need of rescue and rehabilitation. For their part, government officials saw the usefulness of maintaining divisions between women: the system of 'professional prostitutes' was 'vital to maintaining the socioeconomic order,' while wives' sexuality was best confined to the home; thus, a wife's commission of adultery was considered a criminal offense.[2] In one attempt to tear down such divisions, the reformers petitioned the government to prevent the Yoshiwara from being re-built in the wake of a devastating fire in spring 1911. Although this bid failed, reformers achieved victory in their efforts to halt plans for geisha to dance at the enthronement ceremonies for Emperor Taishō scheduled for spring 1915, arguing that it would be an embarrassment for the nation to be represented to the world by prostitutes at this important event. Following on this success in 1915, the Purity Society persuaded the Tokyo Metropolitan Police to prohibit the annual Oiran (courtesan) Parade in the Yoshiwara. Reform-minded women made tours of the Yoshiwara, but only in the context of their campaigns. Consequently, for the Bluestockings to visit the Yoshiwara for sport showed blatant disregard for both the government's and the reformers' sense of the critical divisions formed by gender and class. Their transgression also threatened the tenuous support gained for women's higher education. Leaders in women's education such as Tsuda Umeko and Shimoda Utako and girls' school principals were quick to denounce the Bluestockings.

Tokyo geisha in the 1910s

-

Although 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' aims to ridicule the Bluestockings, as I discuss below, another, equally important part of this comic comes into focus when we shift our attention to the geisha in this story, a woman by the name of Eizan. Notably, the geisha, is not caricatured, but symbolises the world of the pleasure quarters that the New Woman disrupts. The cartoonist exaggerates the disparity between the Bluestockings and the geisha by emphasising the latter's femininity and beauty. Her hair is richly dressed, her kimono luxurious in its folds of material, her body curved and her features fine. A samisen instrument—the sign of the geisha's artistic trade—hangs on the wall behind her. The cage-like structure here suggests harimise, the practice of displaying prostitutes in brothels—something that a geisha of Eizan's stature, however, would not be expected to do. The practice was banned by authorities in large cities such as Tokyo and Osaka in 1916.[3] Nevertheless, the cartoon depicts Eizan as boxed in, awaiting clients. She appears fixed and docile, the one who is gazed upon. In contrast, the New Women, claiming the same mobility and voyeuristic power as men, travel freely among urban spaces, even to the Yoshiwara. Viewing the activities of Tokyo geisha, and even the Bluestockings' fictional geisha characters, reveals a far more complex picture of their lives, attitudes and cultural personae than 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' suggests. Indeed, even this short overview of Tokyo geisha in the 1910s illustrates their own intent to participate in modernity.

-

In 1912, the numbers of geisha were on the rise. Liza Dalby cites that there were about 2,300 geisha in Tokyo in 1905 and almost 10,000 by 1920.[4] Geisha in the high-ranking quarters of Asakusa, Shinbashi and Yanagibashi practised the arts, entertained men who were leaders of government and industry and were also popular with foreign tourists from the U.S. and Europe. Of course, it is important to remember that 'geisha' was an elastic term, one that could describe women of these glittering heights as well as those forced into brutal sexual labour.[5] Scholarship on the Bluestockings' visit to the Yoshiwara reflects the blurred boundaries between geisha and prostitutes; the Daimonjirō is described alternately as a 'brothel' or a 'teahouse' and Eizan, termed a 'courtesan' or a 'geisha.'

-

In the Meiji Era, many high-ranking geisha were as intent on participating in the public sphere as reformers and Bluestockings. Meiji geisha, for instance, engaged in the 1890s vogue for public speech-making, supported the People's Rights Movement (Jiyū Minken Undō), and argued for rights for geisha.[6] In support of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, geisha united to form the National Conference of the Confederation of Geisha Houses.[7] Geisha experimented with Western fashions; in the early 1900s, even dressing as girl students when their attire became the look of the moment.[8] In the 1910s, the most celebrated among them were the popular subject of postcards, cosmetics advertisements in newspapers, posters in store windows, and pictorial albums sold in Japan and abroad. When prohibited from officially participating in the Taishō enthronement gala, geisha staged parades on their own in various places in Tokyo on the first day of the ceremonies.[9] This resistant celebration proved that like the New Women traipsing into the Yoshiwara, geisha, too, intended to claim the right of mobility and to perform in public space.

-

Two accounts of the profession penned by geisha themselves in the early 1910s match the assertiveness of these geisha parades with the literary self-expression favoured by the Bluestockings. In 1913, one Yanagibashi geisha by the name of Andō Senko, who was also the daughter of a geisha, published the book Nidai geisha (Two Generations of Geisha).[10] Although the account reportedly complained that there were all too many 'loose geisha

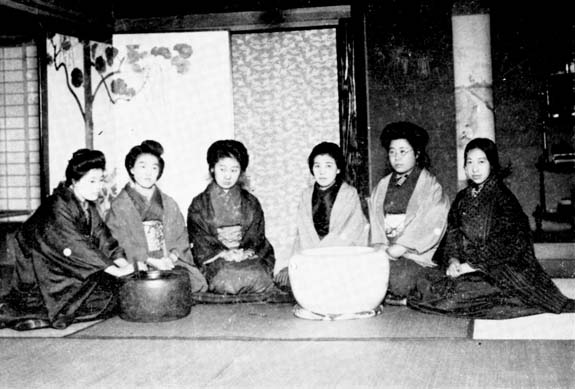

Figure 2. Azuma of Shinbashi. Photograph from Celebrated Geysha (Geisha) of Tokyo: 9 Plates with 105 Portraits. Kazumasa Ogawa, Photographer, distributed by Kelly and Walsh as Sole Agents, plate 1, no. 3, ca 1895.

| |

these days,' Andō firmly associates geisha with the literary arts of the day. She describes their fondness for the journal Bungei kurabu (Literary Arts Club) and comments on many famous male writers including Izumi Kyōka, Kōda Rohan, Natsume Sōseki and Oguri Furyō whom geisha entertained. In November 1916, about six months after the enthronement parades, the Shinbashi geisha Ishii Miyo published Geisha to machiai (Geisha and Teahouses), a book that has since been reprinted.[11] In her foreword to the book, Hiraoka Shizuko, a Shinbashi geisha house manager (ōkami), defends the geisha, declaring that Western ladies appreciate their dances and Westerners of both sexes understand the true role of geisha. While not completely divorcing geisha from prostitution and arguing that prostitution also occurs in the West, Hiraoka commands those who attack geisha to turn their criticism on men and the demands of the era. Geisha to machiai details several aspects of the geisha's life (her income and expenses, her daily routine, the geisha's appearance and language, her arts training) and the teahouse business (the maids, the different kinds of clients). Ishii writes of her good luck in being a geisha, speaks proudly of geisha as trend setters, and declares that geisha who respect the 'sacredness of their profession' need not be apologetic. Ishii describes the various geisha communities in Tokyo and defends the teahouse as an elite institution that does not sell sex, but rather intends to help men forget the competitive world of work and provide a place for private conversations. She also proposes that eventually there will come a time when 'teahouses for ladies to enjoy' will emerge. Intriguingly, Ishii appropriates the language of the Bluestockings, stating that geisha, too, must awake and become New Women, and men also need to make every effort to come to their senses before they get the cold shoulder from geisha.[12]

|

-

Returning to 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' and the geisha's lack of caricature, we can see that the Bluestockings' transgression was deemed so shocking that it overshadowed the 'problem' of geisha, who, according to the cartoonist, at least remained confined to the teahouse at this point. If well-bred young women were ignoring the boundaries of propriety by taking to the teahouses, what ill might befall the nation next?

The Bluestockings and their experience of the Yoshiwara visit

Figure 3. Cover of Seitō (Bluestocking), September 1911

-

Since the Bluestockings have earned much scholarly attention, I give only a short introduction here. The Bluestockings had not set out to be New Women; it was the media that initially gave them this title. Educated daughters of a new middle class, they had achieved fame by initiating a women's literary journal in 1911, also known as Seitō or Bluestocking. The journal—written almost exclusively by women—reflected the eclectic literary tastes of the day, including haiku, experimental poetry, plays, and confessional stories, and many translations of European literature of the 1890s, a literature often dubbed decadent and erotic. But what really stirred attention and ultimately made them New Women was the way that the Bluestockings spoke honestly of their personal lives in the journal, their hopes and frustrations, and increasingly, their displeasure with the expectations for women of their class to become patriotic, modest 'good wives and wise mothers' (ryōsai kenbo). By 1912, they were also raising eyebrows for the reputedly bohemian nature of their personal tastes. The Bluestockings were rumored to frequent cafés, imbibe Western liqueurs, fawn over European literature, and prey on innocent young men. One famous incident that gave life to such rumours occurred when one of the youngest members, the impulsive, fun-loving Otake Kōkichi, wrote passionately in Seitō about Bluestocking leader Hiratsuka Raichō, entertaining in her room at night 'a beautiful young boy (bishōnen) of fifteen or sixteen' who was intoxicated from drinking a rainbow concoction of alcohol; the story was picked up by the Kokumin Shinbun (Citizen's News), but the reporter failed to realize that the 'boy' was none other than Kōkichi who was describing her own infatuation with Raichō.[13] Raichō's colourful past made such stories easy for the public to believe; author Morita Sōhei based his 1908 novel, Baien (Black Smoke), serialised in a national newspaper, on his relationship with Raichō, describing their meetings at teahouses, their mutual love of decadent literature, and their bizarre flirtation with double suicide. In the public's mind, this notorious Bluestocking was also the 'Baien Woman.'[14]

-

The Yoshiwara Visit Incident (Yoshiwara Hōmon Jiken), which also involved Kōkichi, only confirmed the worst suspicions about the Bluestockings' predatory nature and lack of virtue. Although many women left the Bluestockings at this point, others joined and confronted public opinion by adopting the title 'New Woman' (atarashii onna), holding a public lecture on the topic, and discussing it through debates with each other and by translating New Woman essays from the West. In the spring of 1913, the government issued a warning, obviously directed at the Bluestockings, that it would take action 'to prevent the minds and morals of men and women students from being corrupted by the subversive ideas and salacious writings of the women who declare themselves New Women.'[15] Despite this warning and public outcry, the Bluestockings continued to write as they pleased, taking on controversial topics such as chastity, abortion and prostitution. When the journal's financial problems and the complications of their personal lives led the group to fold, reports of open marriages, divorce, and even an attempted murder kept several members in the public eye.[16] The last of the fifty-two monthly issues of Seitō was published in February 1916.

-

Among all the scandals associated with the Bluestockings, few were as memorably exaggerated in the press as the Yoshiwara visit. Briefly put, the one-night visit by three Bluestockings (Hiratsuka Raichō, Nakano Hatsuko, and Otake Kōkichi) might have ended as a mere curiosity of their youth had not journalists got word of the event from Kōkichi speaking so freely afterwards. The idea for the visit came from Kōkichi's uncle and supporter of the Bluestockings, the painter Otake Chikuha, who argued that the Bluestockings must take into account the plight of women sold into prostitution when arguing for women's emancipation. Familiar with the Yoshiwara, Chikuha made the arrangements for the women to visit one of the quarter's highest class teahouses, Daimonjirō, accompanied them there, and paid the expenses.[17] There, the Bluestockings met Eizan, a woman who improved on her plainness 'with a skillful use of cosmetics, a becoming hairstyle, and elegant kimono.'[18] They discovered that Eizan was also a graduate of Tokyo's elite Ochanomizu Girls School. Displayed in one corner of the room in the teahouse reserved for Eizan was a paper doll made by Tamura Toshiko, a writer who had gained a reputation as a New Woman. One wonders whether the doll revealed Eizan's interest in the New Woman or simply modern trends. In her autobiography, Raichō writes that Eizan 'seemed reluctant to tell us anything that might be considered confidential. Her feeling was understandable. She had never entertained women customers and had no way of knowing what kind of women we were, though we were about the same age.'[19] Raichō recalls that although she and her friends were aware of reformers' efforts to abolish prostitution, they went to the Yoshiwara merely out of curiosity. Yet her 'curiosity' about the Yoshiwara apparently did not extend very far. Even writing decades later in her autobiography, she does not consider why an Ochanomizu graduate ended up in a teahouse, although the common assumption would have been that Eizan's family had suffered some grave financial loss. Despite her visceral aversion to the ways that the Meiji gender system impinged on her own life, Raichō shows startlingly little empathy for Eizan nor is she even moved to comment on the precarious quality of women's socio-economic status. As Hiroko Tomida observes, the experience did not push Raichō to expand her fight against gender constraints to women outside her own class at this point.[20]

-

The Bluestockings' visit to the Yoshiwara did lead to repercussions within the group. One member, Yasumochi Yoshiko, wrote to Raichō to express her disappointment in the reckless frivolity of the event, complaining that their journal was going to be seen as nothing more than a vehicle for tomboyish defiance of convention.[21] Kōkichi took a completely different tact by striking up a correspondence with Eizan. Unfortunately, when reporters got wind of this, as Dina Lowy has discussed, they used this friendship to explore 'Kōkichi's irregular sexual proclivities,' spinning reports of her predilection for same-sex love and speculating that her fondness for prostitutes dated back to her childhood visits to the quarters.[22] Fearless, Kōkichi published a short, rather roundabout essay in 1913 in the influential journal Chūō Kōron (Central Review) in which she perceptively critiqued the way patriarchy divided women into those who could be visible and those who must be hidden.[23]

-

The cartoon humour of 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' finds its match in newspaper send-ups of the incident. Reading these, too, helps us understand how exaggeration pushed the public to laughter and shock at the same time. The press, in its eagerness to brew a scandal sure to sell papers, created the Bluestockings—and by extension, the New Woman—as defined by their appetite for pleasure, their voyeuristic curiosity about the sexuality of others, and their lack of anything that might be called 'feminine modesty.' I paraphrase and quote from the account in Hiratsuka Raichō's 1971–72 autobiography brilliantly translated by Teruko Craig. As Raichō recalls: The Tokyo Nichi Nichi (Tokyo Daily News) depicted the Bluestockings as being ferried in three rickshaws, whose noisy runners gave 'lusty shouts' as they brought them to a teahouse, and then dashed them off to a geisha house in the Yoshiwara by the name of Daimonjirō, where, the reporter explained, the three 'tasted the offerings of the pleasure quarters to the full.' So curious were these New Women that they had to depart the Daimonjirō early the next morning to rush back to the first teahouse in order to get a peek at the customers 'taking their leave of the geisha.' Apparently overcome with all this excitement, 'Kōkichi fell to the ground, senseless,' but recovered in time to join her Bluestocking mates on their way home as they went 'swaggering along the banks of the Sumida River,' acting for all the world like three young rakes on the heels of an excellent adventure.[24] Later newspaper reports said that the Bluestockings had actually spent three nights in the Yoshiwara, which would have been quite a debauchery indeed.

-

Like the back story of reformers and geisha, the reputation of the Bluestockings enhances our reading of 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara.' The caption to the comic reads, 'Yoshiwara tōrō' (literally, Visit to the brothel of the Yoshiwara), underscoring the geisha's link to prostitution and the Bluestockings' predatory sexual desire. The figures on the right caricature two Seitō founders Hiratsuka Raichō and Nakano Hatsuko. An insert to the right proclaims that they are 'Japan's Noras' (Nihon no nōra), a reference to the excitement stirring over the production of Henrik Ibsen's play Doll House in Tokyo that year, and especially the debate over Nora's impulsive decision to walk out on her family and the new presence of actresses on the Japanese stage. The cartoonist draws the Bluestockings as ungainly, as homely and even as sprouting whiskers, as if to say, 'Look, I am a New Woman —I'm a man!' The Raichō figure wears her customary hakama, a divided skirt fastened over a kimono that made walking easier and that, despite being seen as masculine, had become the uniform of the time for girl students. 'Bluestocking' written in English and over every inch of the women's costumes further connects them with the foreign and New Women abroad, and marks them as boastful of this bilingual identity. The New Woman's intellectualism and love of literature is referenced by Raichō's spectacles and the open book in her hand. She leers at the geisha in cold fascination as if inspecting an animal in the zoo while the geisha recoils in horror at the comically disturbing sight of this ugly, staring New Woman.

-

Ridicule of the New Woman in 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' recalls numerous, equally satiric representations of the New Woman in the Euro-American West. Cartoons of the New Woman typically focused on the woman's physical appearance and sexual identity. They 'were riddled with contradictions,'[25] faulting the New Woman for being at one extreme or the other on a continuum of sexuality or off the chart altogether. She was alternately a decadent, rapacious femme fatale, grotesquely masculine, or a sexless shrew. In the mid-1890s, for example, the British press stamped the New Woman as a mannish type who puffed cigarettes while attired in dark, severe men's fashion, spectacles perched on her nose and books strewn about her. Such imagery instilled suspicion that the New Woman had no interest in home-making and child-care, and sought only to appropriate the privileges and appetites of men, threatening to erase the distinctions between feminine and masculine altogether, and sending men into the arms of women of lower classes. [26] These cartoons were intended to be disciplinary as well as funny. As Peter Duus has observed, Tokyo Puck and other Japanese humour magazines similarly used condensation, simplification and distillation to create a 'visual epigram' that incited laughter, reinforced types and, most effectively, reassured the viewer that 'we' were 'superior to a foolish, stupid, or corrupt "them."'[27] By deriding the Bluestockings as homely oddballs, 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' warns women away from emulating them. It also diverts attention from the gender politics operating in the Yoshiwara that privilege men. As Martha Banta writes, 'Caricature is held as proof of the presumed rightness and literal value of the eternal ideals it visually challenges.'[28]

-

Revulsion at the Bluestockings' 'mannishness,' as Dina Lowy has shown, were rife in other publications, too. Observing that the New Woman's alleged desire to grow facial hair fuelled criticism in both the U.S. and Japan, Lowy points to one 1913 article on Raichō in which the author recounts having counted thirty hairs on her chin.[29] Disapproval of Kōkichi in the wake of the Yoshiwara Incident also faulted her unusual height, size and masculine dress, leading one reporter to comment that she 'did not look like a woman.'[30] Such criticism of the New Woman as masculine also hints at the public's sense of the dangers associated with lesbianism, especially among school girls who might fail to mature past sisterly bonds with schoolmates to heterosexual love and motherhood. Consequently, the Bluestockings are caricatured as deviant in their desire for other women, for appropriating the privileges of men by acting like men, and for making fools of themselves by their appearance. Interestingly, as Michiko Suzuki has discovered, however, Seitō carried few pieces on same-sex love, and those few that were published 'express anxiety about the difference between innocent friendships and abnormal relationships.'[31]

-

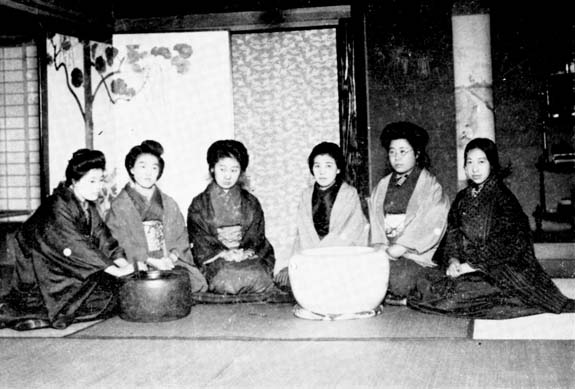

Others chastised the Bluestockings for their sexual pursuit of men. Iwata Nanatsu has discovered several instances in the popular literature of the day that disparaged or satirised the Bluestockings by likening them to prostitutes and geisha. In 1916, critic Takajima Beihō wrote in Chūō kōron that he could see nothing else in the New Woman's future—whether she was a writer or an actress—than becoming an 'art-woman-geisha-kind-of-concubine-New Woman.' He could imagine no alternative for the New Woman than becoming a strange combination of existing female types.[32] Iwata cites a satiric travel guide to Tokyo published in 1914 that reported how the reader could go to the 'Seitō office-teahouse' and see Kōkichi and Raichō soliciting men with comments such as 'Here danna-san' (Here, Master) and 'Misutaa, kamu iin' (Mister, come in).[33] Similarly, a March 1914 article in the journal Shinchō (New Wave) described the Bluestockings as whores (jorō), referring to a photograph, which was one of the very few that the members published in Seitō, that depicts five of the Bluestockings at their 1914 New Year's Party. They are sitting modestly and the name of each woman is given. The Shinchō writer admits that it is rude to say so, but every time he looks at this picture, he imagines the harimise slats over it. In other words, for these women writers to appear named and photographed in public, especially in the wake of the scandals, makes them equal to prostitutes on display.[34]

Figure 4. The Bluestockings' New Year's Party, 1914. Pictured from left are Kobayashi Katsu, Iwano Kiyo, Nakano Hatsu, Araki Ikuko, Yasumochi Yoshiko, and Hiratsuka Raichō. The photo appeared in Seitō, vol. 4, no. 2 (February 1914).

-

It helps us to interpret such reports and 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' if we broaden the visual context. The comic sight of the Bluestocking writers cavorting in the Yoshiwara resonates with the publication of earlier images that likened the woman writer to a geisha. In her excellent study of Meiji women writers, Rebecca Copeland describes how in the 1890s women writers were described as 'flowers, beauties, bright splashes of color.'[35] She discusses how the 1895 January issue of the popular journal Bungei kurabu featured pictures of women writers much in the way it displayed geisha in other issues. Copeland notes how the montage of the writers' photographs replicated that of bijin (beauties), eroticising the writers. The editors imply that a 'woman who sells her fiction is little more than a woman for sale,' and thus, despite lofty claims to female essence and femininity, the woman writer 'allowed herself to become a public commodity.'[36] The situation had not changed by the 1910s as the Bluestockings' case proves. These attitudes not only disparage the Bluestockings and other women writers, but also reinforce contempt for geisha and prostitutes, upholding the prerogatives of the male consumer to objectify and commodify women. Such efforts to discipline women, ridiculing them for transgressing social borders, also indicates male fears of losing control over the situation and their privileged status. As Raichō summed up the reason for public outrage, 'the much-discussed New Woman had dared to venture into man's preserve.'[37]

Bluestockings' stories about geisha

-

Although 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' depicts Bluestockings peering voyeuristically at the geisha who is horrified by the sight of them, the reality of their interest in geisha is more ambivalent and interesting. As Iwata shows in her perceptive chapter on Bluestockings' fiction about geisha, the Bluestockings were curious, and certainly were aware of the celebrated status of the reigning geisha beauties.[38] Generally, however, it was important to the Bluestockings' own identity as educated, intellectual women to see themselves as superior to the geisha (and to well-educated, but conservative women as well). They saw the geisha as linked to old-fashioned romances, as in a sense, as Iwata remarks, rather like a mirror image of their own modernity. While the Bluestockings understood the ideal marriage as a companionate relationship built on the union of the flesh and the spirit, and freely chosen by a couple, the geisha (and most middle-class wives, for that matter) epitomised a woman's financial dependence and subservience to a man. Nevertheless, two stories, discussed below, that Iwata analyses, show a grudging admiration for the assertive, forthright quality of geisha who understand and manipulate the system to their own advantage rather than trying to change it. They offer a provocative contrast to the idealistic, romantic and naive character of the young New Woman, frequently depicted in Seitō fiction as doomed to disillusionment in love.

-

In the first story, an older brother's romance with the geisha Otoya gives the narrator pause in Hayashi Chitose's 1912 short story, 'Otoya to ani' (Otoya and My Older Brother).[39] Told in the voice of a concerned younger sister, the story presents the geisha as independent and self-assured, but also opens a window on privileged girl students' belittling of her as uneducated. Otoya appears in only one short, opening scene of the story, which shows the brother's discomfort when Otoya dresses to go out, but refuses to say where she is going. When he protests, she responds that he does not report his comings and goings to her, and she has no obligation to provide this information to him. The scene is somewhat reminiscent of Ibsen's Nora departing her house, but unlike Nora, this geisha is self-supporting, confident and knows exactly where she is going. Introducing Otoya in this fashion gives the reader privileged knowledge of the geisha. The rest of the story concerns the younger sister's curiosity about Otoya, whom she has never met. Hearing that Otoya is one of the elite Shinbashi geisha, the 'stars' of the day, the sister assumes that she must be beautiful, perhaps even one of the geisha that appeared in the magazines, and she wonders what age she might be. Without describing her brother's romance, she asks her friends at school one day for their opinion of geisha. Hayashi imagines the girls answering in rapid fire with sharp distaste: geisha are uneducated and disgusting. Since the younger sister believes that her elder brother truly loves Otoya (and is not simply interested in a sexual relationship), she hopes that he will educate her, protecting her from this scorn. The budding New Woman wants to rescue the geisha as much as reformers do. Yet, as Iwata observes, the story subtly calls into question the girls' sense of superiority. Hayashi's emphasis on Otoya's assertiveness alerts the reader that this woman will not be easily moulded by another, and that her position as a geisha has given her a more critical vision than that provided to the students by the good wife, wise mother rhetoric of their school. In effect, the story questions why the girls disdain the geisha, but do not call the brother's virtue into question.[40]

-

The gap between the Bluestocking and the geisha, and high hopes for romantic love, are also dramatised in Ueno Yō's 'Nyōbo no hajime' (The Beginning of Wifehood), which tells the tale of Teruko, a young New Woman who fully enjoys an independent life in Tokyo and plans to maintain this life even after marriage to her beau Utsumi. Shortly after their wedding, however, Utsumi persuades Teruko to give up her Tokyo life to be with him in Nagoya. Doing so and taking on all the associated expectations bring Teruko to 'the beginning of wifehood.' Teruko dislikes the way Utsumi falls into treating her as a wife, addressing her disrespectfully as omae (informal version of 'you') and leaving her at home when he goes out to parties. This was not the 'modern home' of her dreams. Teruko becomes truly disillusioned when she learns that Utsumi has long had a relationship with a favorite geisha by the name of Koyoshi. Knowing that her husband has had sex with another woman fills Teruko with bitterness. Later in the story, Teruko actually meets one of her husband's geisha friends when one named Tarō pays her a visit, bringing along her four-year-old son. Unsure what linguistic register to use, Teruko ends up deciding to talk with her as a friend which leads to an easy, pleasant conversation. Teruko finds the geisha clever and is interested to hear about her world. Notably, this conversation does not frame Tarō as a crude person or one in need of rescue. Rather, as Iwata surmises, it creates a mirror image of two women divided by class and sexual politics; only the man is able to freely traverse the divide.[41] But Teruko's attitude toward the geisha is ambivalent. Later in the story, she cannot abide the fact that her husband has touched both 'her sacred self' and 'that disgusting woman.' In the end, the story most strongly expresses Teruko's deep sense of injustice at the way society expects a wife to suffer the affairs of her husband while remaining chaste herself. She also believes that such infidelity sullies their love and their own sexual relationship.[42] Much like geisha Ishii Miyo, Ueno condemns patriarchal privilege. Yet her main interest is not a defence of the geisha, who seems comfortable with the system and her place in it, but rather concern for the ways a New Woman's hopes for fidelity in her supposedly modern marriage are apt to be dashed.

-

While the Bluestockings did not see themselves as particularly similar to the geisha, they did have in common experiencing the attacks of reformers such as the JWCTU and women educators. Bluestocking Itō Noe famously refuted this criticism in her Seitō essay, 'Arrogant, Narrow-Minded, Half-Baked Japanese Women's Public Service Activities.'[43] She accuses these women's groups of lacking compassion for women associated with the sex trade and for using their contempt for them as a means to magnify their own virtue. Noe's essay launched a debate with socialist Yamakawa Kikue on the causes and possible solutions for ending prostitution.[44] Although their debate showed concern for prostitutes, women in the sex trade were still framed as a problematic other. Perhaps the most provocative comment on the prostitution issue came a couple years later from Hiratsuka Raichō who argued in 1917 that in a marriage not based on love, the wife was no different than a prostitute.[45]

Conclusion

-

The focus on sexuality in the New Women (and the non-caricatured geisha) in 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' reveals the familiar narrative of modernity that allows only men access to a mode of self-determination that is abstract, aesthetic, and autonomous, and free of physical embodiment. Women, by contrast, are inevitably reduced to their bodies. As Estella Tincknell writes, 'Femininity has thus been the implied "other" of modernity: where the modern subject was cerebral, autonomous, rational, exercising a confident mastery of public space and expert knowledge, femininity was figured as its opposite--bodily, private, emotional, responsive —dependent rather than autonomous.'[46] When the Bluestockings, like New Women abroad, sought to transgress gendered borders, ridicule centred on their sexual deviance. For a woman, even 'looking' in certain spaces was deemed delinquent behavior. As the Bluestockings learned, no matter how cerebral and spiritual they yearned to be, if they were to claim access to self-determination and go forward from the Yoshiwara scandal, they must address the issue of sexuality. Yet, the more frankly they dealt with issues of sexuality and reproduction in their writings, the more they ran afoul of the government and played into the hands of those who wished to style them as consumed by sexual desire.

-

One caveat belongs in this Conclusion, too. Clearly, sympathetic treatment of the Bluestockings and geisha today can easily cast the reform-minded ladies as heartless. Their view of 'fallen women' as culprits is obviously outdated. But it is important to remember how the injustices suffered by wives, whether humiliation, financial precarity, or VD caused by their husbands' extra-marital exploits, motivated the call for reform.

-

Ironically, by the 1920s and into the 1930s, when modern love ideology was becoming popularised, and the numbers of geisha and the newly emerged café girl (jokyū) had increased enormously, the wife was advised to learn from those who plied sex and affection. As Aiko Tanaka has shown, the highly popular magazine Shufu no tomo (Housewife's Companion) warned women not to let the geisha steal their husbands, but to copy her seductive tricks and experiment with cosmetics and fashion in order to keep husbands from wandering. The modern wife should now scientifically manage the home, assume responsibility for the emotional life of her family, and be able to create the allure of the jokyū and the geisha.[47] For her part, one geisha writing in 1930 by the name of Hanazono Utako felt that she, too, had to compete, especially with the jokyū, and that only by bobbing her hair, wearing Western fashions, and chatting about baseball and the radio did she have a chance to do this. She supported women's rights, took up modern dance, and spoke out against patriarchal privilege.[48] Hiratsuka Raichō turned her attentions to campaigns related to women's suffrage, the prevention of venereal disease, and the successful repeal of Article Five of the Police Security Regulations that curtailed women's political activity and right to speak in public on political issues. By the 1930s, the barriers between women that had made 'Dalliance in the Yoshiwara' strike the chord it did, had blurred, and a new politics of pleasure and sexuality was on the rise.

Endnotes

[1] For an in-depth discussion of the reform movement, see Elizabeth Dorn Lublin, Reforming Japan: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in the Meiji Period, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2010.

[2] Sheldon Garon, Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997, pp. 101–02.

[3] Garon, Molding Japanese Minds, p. 97.

[4] Liza Crihfield Dalby, Geisha, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983, p. 71.

[5] Stories of women sold into prostitution and low-class geisha houses by their impoverished families are recorded in Mikiso Hane, Peasants, Rebels, Women, and Outcastes: The Underside of Modern Japan, Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

[6] Marnie S. Anderson, A Place in Public: Women's Rights in Meiji Japan, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2010.

[7] Dalby, Geisha, p. 70.

[8] Rebecca Copeland, 'Fashioning the feminine: images of the modern girl student in

Meiji Japan,' U.S.-Japan Women's Journal, 30–31 (2006): 13–35.

[9] Okano Yukie, 'Kaisetsu: Geisha to machiai, Ishii Miyo' (Analysis: Geisha and Teahouses by Ishii Miyo), in reprint of Ishii Miyo, Geisha to machiai, Tokyo: Nihon Shoin 1916 in the series Josei no mita kindai II:001 (Modernity as Seen by Women, II:001), Onna to rōdō (Women and Labor), Tokyo: Yumani Shobō, 2004.

[10] Okano Yukie references Andō Senko's Nidai geisha (Two Generations of Geisha) as being published in 1913 by Shin'eisha Shuppan. Okano, 'Kaisetsu,' pp. 4–5. I could not find any reference to this, however, in World Catalogue. Okano surmises that there is also the possibility that these accounts were not written by the geisha, but by editors who interviewed them.

[11] Okano Yukie, 'Kaisetsu: Geisha to machiai, Ishii Miyo' (Analysis: Geisha and Teahouses by Ishii Miyo), in reprint of Ishii Miyo, Geisha to machiai, Tokyo: Nihon Shoin 1916 in the series Josei no mita kindai II:001 (Modernity as Seen by Women, II:001), Onna to rōdō (Women and Labor), Tokyo: Yumani Shobō, 2004.

[12] Geisha to machiai, originally published by Nihon Shoin in 1916, was reprinted in 2004 in with an excellent afterword by Hosei University lecturer Okano Yukie. Okano references Andō Senko's Nidai geisha (Two Generations of Geisha) as being published in 1913 by Shin'eisha Shuppan; I could not find any reference to this, however, in World Catalogue. Okano surmises that there is also the possibility that these accounts were not written by the geisha, but by editors who interviewed them.

[13] Sharon L. Sievers, Flowers in Salt: The Beginnings of Feminist Consciousness in Modern Japan, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983, p. 173. Known as the 'Five-colored liquor incident' (Goshiki no sake jiken), this case has been scrutinised among Seitō scholars, especially for the way it has led to discussions of perceptions of tlove at the time in public, among the Bluestockings, and in later memoirs by Bluestockings. See, for example, Dina B. Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman': Images of Gender and Modernity, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007; Otsubo, Sumiko, 'Engendering eugenics: feminists and marriage restriction legislation in the 1920s,' in Gendering Modern Japanese History, ed. Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2005, pp. 225–56; and Gregory M. Pflugfelder, '"S" Is for sister: schoolgirl intimacy and 'same-sex love' in early twentieth-century Japan,' in Gendering Modern Japanese History, ed. Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2005, pp. 133–90.

[14] Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman', p. 67; Morita Sōhei, Baien (Black Smoke, 1909), vol. 29 in the series Gendai Nihon bungaku taikei, reprint Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō 1971.

[15] Teruko Craig's translation. See Hiratsuka Raichō and Teruko Craig, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist, New York: Columbia University Press, 2006, p. 219.

[16] Information from Hiratsuka Raichō's perspective about the 1916 Hikage Inn Incident, which brought to a head the fraught relationships among anarchist Ōsugi Sakae, his wife Hori Yasuko, and his lovers Itō Noe and Kamichika Ichiko, can be found in Hiratsuka and Craig, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, pp. 246–47. For analysis of the famous divorce suit filed by Bluestocking Iwano Kiyo against her husband, Naturalist writer Iwano Hōmei, see Jan Bardsley, The Bluestocking of Japan: New Women Essays and Fiction from Seitō, 1911–16, Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 2007, pp. 157–60.

[17] Tomida, Hiratsuka Raichō, p. 172.

[18] Hiratsuka, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, p. 180.

[19] Hiratsuka, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, p. 180.

[20] Tomida, Hiratsuka Raichō, p. 173.

[21] Hiratsuka, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, p. 181.

[22] Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman', p. 62.

[23] Otake Kōkichi, 'Geishōgi no mure ni taishite (Regarding groups of geisha and licensed prostitutes), Chūō Kōron (January 1913): 186–89; for more analysis, see also Iwata Nanatsu, Bungaku to shite no Seitō (Seitō as Literature), Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan, 2003, pp. 50–51.

[24] Hiratsuka, Craig, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, p. 178.

[25] Sally Ledger, The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle, Manchester, UK: Manchester University PRess, 1997, p. 16.

[26] Michelle Elizabeth Tusan, Women Making News: Gender and Journalism in Modern Britain, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005, p. 135.

[27] Peter Duus, 'Presidential address: weapons of the weak, weapons of the strong—the development of the Japanese political cartoon,' Journal of Asian Studies, 60(4) (Nov. 2001): 965–97.

[28] Martha Banta, Barbaric Intercourse: Caricature and the Culture of Conduct, 1841–1936, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003, p. 4.

[29] Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman', p. 97.

[30] Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman', p. 62.

[31] Michiko Suzuki, Becoming Modern Women: Love and Female Identity in Prewar Japanese Literature and Culture, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010, p. 29. For discussion of the same-sex love relationship between Kōkichi and Raichō, see Lowy, The Japanese 'New Woman'; Otsubo, 'Engendering eugenics'; Pflugfelder, '"S" Is for sister'; and Tomida, Hiratsuka Raichō,.

[32] Takajima Beihō, 'Atarashii onna no matsuro o chōsu (Mourning the fate of the New Woman),' Chūō Kōron (June 1916), as cited in Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, p. 34.

[33] Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, pp. 33–34.

[34] 'Takujōgo' (After-Dinner Speech), Shinchō, vol. 22, no. 2 (February 1915), as cited in Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, pp. 32.

[35] Copeland, Lost Leaves: Women Writers of Meiji Japan, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000, p. 218.

[36] Copeland, Lost Leaves, p. 221.

[37] Hiratsuka, Craig, In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun, p. 181.

[38] Iwata Nanatsu, 'Hayashi Chitose, 'Otoya and Older Brother,' and Ueno Yō, 'The Beginning of Wifehood,' Chapter Two in Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, pp. 32–52.

[39] Hayashi Chitose, 'Otoya to ani' (Otoya and Older Brother), Seitō vol. 2, no. 4 (April 1912), pp. 58–66.

[40] Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, pp. 41–42.

[41] Iwata, Bungaku to shite no Seitō, pp. 47–48.

[42] For New Woman idealisations of romantic love and the union of flesh and spirit in marriage, see Suzuki, Becoming Modern Women, 2010.

[43] Itō Noe, Gōman kōryō ni shite futettei naru nihon fujin no kōkyō jigyō ni tsuite, Seitō, vol. 5, no. 11(December 1915), pp. 1-18) is partially translated in Hane, Peasants, Rebels, Women and Outcastes, pp. 277-82.

[44] For more on the Itō-Yamakawa Debate, see Bardsley, The Bluestockings of Japan, pp. 128–31.

[45] Hiratsuka Raichō, 'Yajima Kajiko-shi to Fujin Kyōfūkai no jigyō o ronzu (Comments on the enterprise of the women's reform society and Ms. Yajima Kajiko), Shin shōsetsu (New Fiction), (June 1917) as cited in Iwabuchi Hiroko, 'Sekushuaritei no seijigaku e no chōsen: Teiso, datai, haishō ronsō' (Challenging the politics of sexuality: debates on chastity, abortion, and the abolition of licensed prostitution), in Seitō o yomu: Blue Stocking (Reading Seitō: Bluestocking), ed. Shin Feminizumu Hihyō no Kai, Gakugei Shorin, 1998, pp. 305–31, p. 326.

[46] Estella Tincknell, 'Scouring the abject body: Ten Years Younger and fragmented femininity under neoliberalism,' in New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism, and Subjectivity, ed. Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff, New York: PalgraveMacmillan, 2011, pp. 83–98, p. 85.

[47] Aiko Tanaka, '"Don't let Geisha steal your husband": the reconstruction of the housewife in interwar Japan,' U.S.-Japan Women's Journal, 40 (2011): 122–46.

[48] Hanazono Utako, Geigi tsū (Geisha Chic), originally published in 1930 by Shiroku Shoin, reprinted in the series Josei no mita kindai II:001 (Modernity as Seen by Women, II:004), Onna to rōdō (Women and Labor), Tokyo: Yumani Shobō, 2004.

|