The 'Nursing Dad'?

Constructs of Fatherhood in Chinese Popular Media

Xuan Li

Introduction

-

In recent years, the field of Asian studies has witnessed the blossoming of research on men and masculinities. Kam Louie took inspiration from traditional Chinese literature and proposed the wén-wŭ (the warrior and the scholar) typologies of ideal Chinese manhood,[1] which is further complemented by Bret Hinsch's detailed chronological accounts on changing masculinity ideals across Chinese history.[2] Derek Hird[3] and Geng Song[4] have zoomed in on contemporary Chinese media to capture the latest construction of Chinese manhood. This growing body of research provides rich empirical evidence and powerful conceptual tools for the study of men and masculinities in historical and modern China.

-

Much of the discussions on Chinese males, however, are contextualised in men's interaction with adult peers, either with females during sexual encounters,[5] or with 'bros' in the homosocial circle,[6] or with professional partners or competitors in work or leisure settings;[7] little attention has been given to Chinese males in intergenerational relationships as parents of young children. In comparison to the scholarship on Chinese females, where the parent-child relationship occupies a central position,[8] studies on Chinese fathers are scarce; in-depth analyses of public perceptions of Chinese men's role as parents barely exist.[9]

-

In this study I explore key themes of fatherhood in contemporary Chinese society by analysing a popular reality show, Dad, where are we going? (Bàba qùnă’r), aired by Hunan Television since 2013. Building on existing scholarship on Chinese masculinities and fathers, as well as studies using the reality show as a source of social values, I look at the shifting attitudes towards fathers and fatherhood against the backdrop of ongoing social changes in China. In particular, I discuss fathers' parenting desire, their expected parental involvement and parenting styles in today's China, and I explore underlying parental and gender norms.

-

A key concept that underpins my analysis is patriarchy, defined by Steve Harrell and Goncalo Santos as a 'hierarchical system of domestic organization…that builds on multiple sets of intersecting inequalities including control by sex/gender and control by age/generation.'[10] Harrell and Santos contended that classical patriarchy, defined as the dominance of older generations and males over younger generations and females, has undergone major changes in modern China, although the revolution in intergenerational relationships seems to have outpaced that of the gender relationship. Similarly, Yifei Shen argued that China has now entered the stage of 'post-patriarchy' where the senior dominance declines but the male dominance lingers.[11] In this article, I will demonstrate how the social and cultural changes made their imprints on the construction of fatherhood in China along both intergenerational and gender axes, and how changes have taken place to varying degrees along gender and intergenerational dimensions. It is the uneven pace at which the various gender-related sociocultural transformations unfold that contribute to an increasingly complex and fluid picture of fatherhood in reform-era China.

Fathers in Chinese society: A brief history and key concepts

-

The construct of fatherhood in Chinese societies has a complex and fluctuating history. The prototypical 'traditional' father of agrarian pre-modern China combines personal virtues and family ethics of Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism.[12] While certainly not without historical and regional variations, a good Chinese father is generally construed as a benevolent, emotionally well-regulated man who is fluent in social etiquette in different social contexts. A good father of pre-modern China is motivated to carry on the family lineage by reproducing offspring (especially sons), to extend the family glory through professional engagement, and to take on the obligations of providing for the family, decision making, and handling 'external affairs' as the family head while his wife/wives cover the 'interior chores' (as captured in the proverb 'nán zhŭ wài, nǚ zhŭ nèi,' literally meaning 'men in charge of the external and women in charge of the interior'). The father is responsible for his children's behaviour, and duly assumes the roles of disciplinarian, educator and role model. In particular, he should complement the nurturing maternal role by parenting in a kind, concerned yet strict and proper manner,[13] thereby maintaining a 'strict father, kind mother' (yánfù címŭ) constellation.[14]

-

'Traditional' Chinese fatherhood was first challenged in late-nineteenth century as the Qing Dynasty fell into decay in the face of rising capitalist powers. Out of concern over the survival and fate of the Chinese nation, cultural elites of the Republican era (1912–1949), such as the writer Lŭ Xùn (1881–1936), vehemently criticised the oppressing, suffocating, 'cannibalistic' traditions of filial piety and male superiority, and called for an enlightened and child-centred parenting approach. The fatherhood ideal of this time—at least among the reform-oriented cultural elites—was marked by a radical departure from the desirable father persona in 'feudal' China and the embracing of a refreshingly liberal parental figure who strove to provide his children 'a healthy physique, the best possible education, and full-scale liberation.'[15] As the parenting discourse of this time is grounded in concerns over the Chinese nation, the discussions of the 'good' father were political rather than practical, and the ideal paternal figure represented a model for both fathers and mothers.[16]

-

The Confucian family ideologies were further denounced during the Communist movements in the 1950–1970s. The land reform (1948–1951) and industrialisation during the early socialist campaigns shattered the economic foundation of the patriarchal kinship system, and the socialist mores reconstructed public attitudes towards fatherhood. The socialist state, by sponsoring work-place affiliated institutional childcare[17]—hough not always for children under three—executed the role of the 'caring parent surrogate.'[18] As argued by Hanna Nielsen in her analysis of contemporary Chinese films, parental roles as breadwinners, educators and family authority were rendered unnecessary in this new context, and fatherhood became so incompatible with their public responsibilities that they were often removed from family life.[19] The popularisation of the 'selfless and asexual Maoist revolutionary hero'[20] further undermined the Chinese men's significance in the family. The male role models of this era, from 'grassroot' model labourers such as the soldier Léi Fēng to the Prime Minister Zhōu Ēnlái, were either childless themselves or so devoted to the socialist cause that they barely had time for their own families. The prevailing fatherhood ideal in China in the socialist era was thus characterised by absence from childrearing or voluntary abstinence from procreation.[21]

-

In post-socialist China (1978–1990s), the father's functions in everyday family life and child upbringing quickly resurfaced. As the state 'rolled back'[22] childcare support in order to allocate more resources to economic advancement,[23] the responsibilities of provision and care were 'returned' to individuals. The significance of career success and material wealth—the new benchmarks of manhood[24]—also permeates into the barometer of fatherhood, as reflected in the catch phrase 'father competition' (pīngdiē) which highlights the expectation for the father to acquire financial and social capital for his offspring in the fiercely competitive market economy.[25]

-

At the same time, the family planning policy and the gender equality principle promoted by the Chinese state have brought about profound readjustment to intergenerational and gender dynamics.[26] The intense focus on one's 'emotionally priceless'[27] singleton child, as well as the anxiety of raising one's 'only hope'[28] in the globalising capitalist economy, have led to renewed criticism of the rigid, affectionless Confucian or socialist ethics that used to govern Chinese families. Many Chinese were inspired to look for parenting models from economically advanced societies. The transformations in masculinity ideals, which puts increasing focus on confidence and emotionality, also encouraged Chinese males to be more egalitarian, caring, and emotionally expressive in the private sphere.[29] Among these changes in personhood, manhood and parenthood values, the close, intimate, and 'democratic' father-child relationships represented in the Western media—as embodied by the warmly received protagonist Dr. Jason Seaver (Alan Thicke) in the American sitcom Growing Pains[30] —presented a new alternative to the Chinese audience, and propelled Chinese fathers and mothers to reflect on their own upbringing and to revise their parenting scripts.

-

However, doubts and suspicion exist regarding this new 'imported' fathering ideal. It is questioned whether the additional paternal nurturance and care is for the best interest of the singleton children in the long run, as they are already surrounded by doting mothers and grandparents. More recently, the rising nationalist sentiment has triggered the advocacy of 'traditional Chinese' parenting, as embodied by the sensational 'tiger moms' and 'wolf dads.'[31] The yearning for greater emotionality in the family life and the ambivalence of its consequences, the influx of global influence and eagerness to revive the Chinese culture, give rise to multiple and sometimes self-contradicting standards, and make contemporary Chinese fatherhood more diverse, fluid and complicated than ever before.

Examining fatherhood ideals: Methodological approaches

-

In this study, I will use reality show as the medium to explore the complexity of fatherhood ideals in contemporary China. Using a reality show was first and foremost motivated by the popularity of television in Chinese households. According to the Chinese Yearbook of Radio and Television 2010, 99.7 percent urban and 99.3 percent rural households in mainland China have at least one television set. TV programmes, accessible to urbanites and rural residents alike, are one of the most influential mass media in China. As commercial TV channels rely heavily on the allure of their programmes, TV stations in post-socialist China, albeit somewhat bound by the censorship laws, are compelled to produce programmes that appeal to the tastes and values of their audience. Reality TV, in particular, has achieved exponential success over the last few years. Situated 'in border territories, between information and entertainment, documentary and drama,'[32] such programmes offer the audience particular attraction by bringing the personal into public sights. The power of reality TV to represent (at least in part) the 'vox populi'[33] and to offer a widely observable medium to otherwise invisible practices, make them suitable for research on parenting ideologies.

-

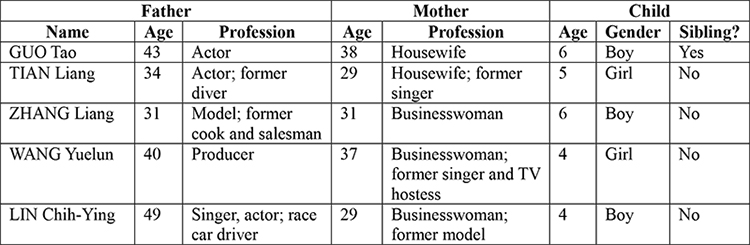

In the reality programme Dad, where are we going, five celebrity fathers were required to take their preschool children on touristic adventures in unfamiliar areas without the children's mothers (see Table 1 for participant information). Following the format of its South Korean original, this show constitutes a mixture of live footage from the participants' trips and interviews with fathers after the trips. The first season featured six trips to various parts of China and was broadcast over twelve 90-minute episodes from October to December 2013. Unlike its South Korean original, which included only father-son dyads, two out of the five participating fathers in the Chinese programme brought their singleton daughters.

Table 1. Information about show participants[34]

-

The show became phenomenal nationwide almost immediately after its premiere and quickly rose to be one of the most watched TV programmes in China in 2013.[35] In different media outlets, viewers eagerly commented on and debated about the parenting behaviour of participants and the expected roles of fathers in general. The huge success of the first season led to two further seasons (with 16 episodes each) as well as follow-up films.[36]

-

Dad, where are we going offers an interesting case for the study of Chinese fatherhood not only because of its wide impact, but also because of its unique format. As the first reality programme in China that put father-child interaction under the spotlight, this programme offers a revealing peek into the otherwise hidden family processes by exposing the most mundane and minute details in day-to-day parent-child interactions. Its inclusion of preschool children considerably enhanced the perceived authenticity of the show by dint of their assumed innocence. The unpredictability of child participants and the improvised behaviour of their fathers not only offered good entertainment, but also ensured credibility. Although the footage was visibly edited and manipulated, as can be seen from the use of exaggerated, cartoon-style commentary, the majority of the audience was convinced of the non-fictional nature of the programme. For example, one viewer commented '[I] cannot help but laugh at the "honest" behaviour of the kids.' Another viewer compared the programme to 'a mirror that reflects the failings of the fathers and their children in real life.'

-

To understand the participating fathers' behaviour, I viewed the first season of Dad, where are we going? repeatedly, and took extensive notes of 1) major events in each episode (e.g. a father-child conflict); 2) the participating fathers' utterances and behaviour towards their children, and 3) the fathers' remarks during the post-travel interviews. I also noted 4) the production team's evaluation of the fathers' behaviour, which often appear as evaluative comments following the participants' action (e.g. a subtitle that reads 'hearty, considerate dad' that appeared during or right after the imagery of a father tucking his child to bed). These notes were then aggregated, repeatedly read and compared following an inductive approach to identify themes and patterns.

-

In addition, I examined Dad, where are we going? from the viewers' perspective, as the investigation of audience opinion 'illuminates ethical values as represented in the programmes and as discussed by viewers.'[37] The audience's comments and discussions were taken from 1) text messages sent from the viewers to the production team during the broadcast, and 2) mainstream online portals and social networking sites in China, such as Tianya BBS, Sina Weibo (Chinese Twitter), Douban and Zhihu (Chinese Quora). Relevant text segments from these sources were documented verbatim, read repeatedly and compared with each other to identify significant themes.

Findings

The ode to the 'paternal instinct'

-

The fatherhood scholarship in Europe and America has a long tradition of investigating the reluctant, irresponsible, even abusive fathers, a tendency that might have stemmed from early studies on the negative effect of absent fathers.[38] Active father involvement, on the other hand, is typically linked with satisfactory couple relationship and spousal support in childrearing.[39] Behind these academic traditions were the child-centred perspective, concern over child and family well-being, and the (mis)assumption that fatherhood is learnt rather than inherent. Unlike women who have the 'innate' passion and talent to care for children, men need extra, explicit encouragement and coaching to parent.

-

In contrast, existing research on Chinese fathers has never questioned the fathers' willingness to procreate and their concerns for their children's welfare, although Chinese fathers were often depicted as uninvolved and emotionally aloof.[40] Susan Brownell and Jeffrey Wasserstrom[41] as well as Susan Greenhalgh pointed out that 'marrying and perpetuating the family line remains a social imperative' for contemporary Chinese males.[42] William Jankowiak[43] and Xuan Li[44] both found that Chinese fathers, while awkward in displays of affection, do feel profound love for their children. Chinese men—much like their female counterparts—are obliged to long for parenthood, to experience 'natural,' spontaneous joy of childrearing, and to devote to—and even sacrifice for—their children without reservation.

-

The strong belief in such 'paternal instinct' was foregrounded in Dad, where are we going?. The very first episode of the programme opens with the celebrity dads—all first-time fathers—recounting their experiences of childbirth. The participant and film producer Wang Yuelun said: 'I was so excited…my mind just went blank. I felt that I should forget my past and start a new life.' Another participant, model Zhang Liang, described how he suddenly burst into tears as he heard his son's first cry from the labour room. Although shock and confusion during the transition to parenthood were also expressed, the advent of fatherhood was depicted as overwhelmingly positive. The participants' accounts jointly outlined a desirable norm, in which fathering is not a choice but a default rite of passage bound to be filled with excitement, elevation and sense of responsibility that one is born to wish for.

-

Fatherhood is portrayed as a pleasant, eventually rewarding experience throughout the programme. This can be best exemplified by the story of Wang Yuelun, who represented a stereotypically uninvolved and incompetent father in the first few episodes: He failed to cook any presentable food, had no idea how to make braids and could not bargain at the market. In later episodes, however, Wang surprised the audience with his significantly improved cooking skills, which he diligently learnt between the shooting because 'it is important that my daughter eats well' (Episode Eleven). Most remarkably, Wang was unfailingly cheered by his four-year-old daughter who generously gave a thumbs-up to his clumsy caregiving attempts and sought him for affection and protection with full trust. Wang himself wrote in a letter to his daughter:

Daddy was not a qualified father and was too trapped at work to understand or take care of you. But in your mind, Daddy is the most competent person, the best one.… Daddy feels immensely guilty about this. Daddy struggled in all the tasks [in the show] and was far from perfect, yet you never complained, but gave me all the recognition instead.

-

Wang's experience was no exception: In Episode Two, the six-year-old son of the model Zhang Liang melted the heart of the audience by looking for a trophy to console his father who faced an unexpected fiasco in a cooking contest. Later in the same episode, former diver Tian Liang's five-year-old daughter surprised her father by a hearty birthday wish despite Tian's failure to sooth her the day before when she got upset. In Episode Ten, actor Guo Tao's son confided to a production team member during a private interview that he really wanted to tell his father that he loves him, although he had complained about his father's harshness. While social desirability and suggestive questioning were almost certainly at play, the children's gestures were largely portrayed as, and indeed perceived by the audience as, genuine and authentic.

-

These episodes and their reception were remarkable in several ways. First, no external motivations—such as spousal encouragement or social pressure—were cited as the driving force for fathers to participate in their children's lives. Rather, the fathers' engagement in childcare was assumed to be willing and spontaneous. Second, Wang's (and other fathers') progress in childcare implied that any man, by dint of his instinctive enthusiasm to father, would be able to master the necessary skillset. Third, the fact that all fathers—regardless of their failings and imperfections—were unconditionally endorsed by their children indicated that the child's love for the father, like the father's love for the child, is innate. By recognising and emphasising men's 'natural' intention to father, their (potential) competence to care, and the positive outcome, the programme constructed fatherhood as desirable, solely from adult men's perspectives. While the fathers' failings and mistakes were teased and ridiculed, they were eventually defended and justified through men's attempts and willingness to be good fathers. The exclusive use of the father's, instead of the children's, the mother's or an external authority's standpoint, hints at the unquestionable orthodoxy of the father as the authority of their own parental norms.

'What you are doing here is gonna win you so many fans!' Rising expectations for paternal care

-

The positioning of care in the framework of Chinese patriarchy is far from straightforward. The existing scholarship on care often discusses the arrangement of childcare in the framework of gender, using the level of childcare division as an egalitarianism indicator.[45] In this narrative, care work carried out by men—due to its opposition to paid employment and its association with femininity—is incompatible with 'hegemonic masculinity.'[46] While such gendered labour division is also prevalent in Chinese societies, care work in Chinese families is arranged according to both gender and intergenerational hierarchies, and assigned to those in subordinate positions of the patriarchal institution (the female) and when necessary, to the older generation (see Esther Goh, Bill Tsang and Srinivasan Chokkanathan in this issue). For Chinese males, hands-on involvement in everyday childcare would not only disrupt the patriarchal gender order but also undermine their authority over children. Interestingly, however, intergenerational hierarchy can override gender norms in the Confucian family ethics. In other words, day-to-day care work is not strictly excluded from Chinese manhood when the care demands can be justified by the intergenerational hierarchy, and especially when similarly positioned females (in the case of care for aging parents, daughters-in-law or unmarried daughters) are not available. Such care relationships, or the expectations of such, can be found in Confucian classics depicting exemplary filial sons who take care of their aging parents (mothers included), as well as in accounts of reform-era Chinese men who are struggling with their filial obligations.[47]

-

The representations of childcare and masculinity in Dad, where are we going? indeed reflect influences of patriarchal traditions. In this programme, childcare was portrayed as essentially feminine. At the beginning of the programme, participants candidly admitted that their wives are the routine caregivers of children (Episode Two), and a large proportion of the live footage was used to depict participants' incompetence in childcare, much like the comic strips in 1940s–1960s American popular magazines.[48] Most participants were caught at their wit's end when facing the 'seemingly simple, yet challenging task' (Episode Two, subtitle by production team) such as preparing basic meals; the only undeterred participant, chef-turned-model Zhang Liang, asked others whether the fact that he could cook is actually undesirable and would 'repel his fans' (Episode One). Such gendered reference of the incompatibility of childcare and masculine identity is fuelled by the production team which, when participating fathers eventually learnt housework and caregiving skills and exchanged cooking tips during later trips, labelled their conversation 'housewife chit-chats' (Episode Four). These remarks jointly implied the norm of a gendered, unequal division of childcare responsibilities, where childcare is exceptional rather than quotidian for fathers.

-

Yet Zhang's fear of losing popularity for performing childcare did not become reality: On the contrary, his cooking skills and fashion taste (as shown in the way he dressed his son) impressed the audience and won him numerous fans. 'Zhang is so hot! Men who can cook are the hottest!' wrote one viewer. Actor Guo Tao put it jokingly in a conversation with Zhang, 'Don't you worry about repelling fans; what you're doing here is gonna win you so many fans!' (Episode 12). Similarly, the images of Lin Chih-Ying telling bedtime stories to his four-year-old son and shielding street noise as the child naps contributed considerably to his reputation. As one viewer concluded, 'The "nursing dads" ( năibà) are now the TV audience's new favourite!' The production team similarly showered the improving fathers with generous encouragement, such as 'Fathers are getting a lot better at caregiving after a few trips with their children!' (Episode Five, subtitle by production team).

-

It is worth noting, however, that the complimentary comments on the fathers' caregiving acts were typically framed with reference to their contributions to child development and to positive father-child bonds; almost no commentator discussed the fathers' enhanced childcare performance in light of gender equality. In other words, the rising paternal involvement in childcare (actual or expected) is not driven by progress in gender inequality, but primarily by an intensified focus on the child in contemporary Chinese families. This development, presumably due to the country's longstanding family planning policy, is in stark contrast with North American or British families where men's increasing engagement in childcare is first and foremost tied with the shift in gender hierarchy and the rising of the 'new lad.'[49] While Chinese fathers are encouraged to participate in childcare as a gesture to forego intergenerational hierarchy imposed by the patriarchal tradition, there are much weaker demands for them to perform childcare for the sake of alleviating their female counterparts from tedious everyday parental responsibilities.

'I need to be a warm father…': Changing parental norms, lingering gender hierarchy

-

A wealth of studies has documented the dramatic shift in Chinese parents' childrearing ideologies in response to China's recent social transformation towards a competitive market-oriented society.[50] Contrary to common belief and previous research, Niobe Way and colleagues found through interviews with Nanjing mothers that urban Chinese parents are deeply concerned about their children's socioemotional well-being.[51] Orna Naftali also observed in Shanghai that urban Chinese mothers are highly aware of children's rights, and are reluctant to violate children's privacy or use corporal punishment.[52] Studies focusing on Chinese fathers hinted that they are following similar trends: Qiong Xu and Margaret O'Brien reported that Shanghai fathers have close, intimate bonds with their adolescent daughters,[53] while Xuan Li's multi-method study on rural and urban Nanjing fathers described a variety of ways (albeit not always explicit) Chinese fathers communicate their paternal love.[54]

-

Dad, where are we going? successfully captured a broad spectrum of fathering behaviour. The production team not only deliberately recruited fathers of varying professions and personalities, but also incorporated challenging tasks and scenarios that would provoke children's disobedience and emotional upheavals, and thereby 'tested' the fathers' skills in managing these situations. The embracing of the warm, gentle parental persona and the rejection of the power-assertive, emotionally distant fathering approach was explicit in the contents and comments of Dad, where are we going?. All five fathers readily praised their children for their achievements and willingly demonstrated parental warmth and affection in public, or at least tried to avoid harsh, punitive behaviour in public sight. When the participants started their first adventure together, for instance, Tian Liang's five-year-old daughter started crying inconsolably out of distress. Tian, after several failed attempt to sooth the child, blamed and shamed her for crying. Tian's response was harshly criticised by viewers as insensitive and problematic (some even suggested that Tian 'should see a therapist'), although Tian later explained that his action resulted from the lack of ready-to-use parenting script for such challenging scenarios, and that he fully appreciated the warm, kind parenting style ('When you have a child [crying like this] in front of all these people you have to be nice to her, you cannot be so harsh; I need to be a warm father…'). Similarly, actor Guo Tao, who used his signature stern look to hush his six-year-old son and persistently pushed his son to complete difficult tasks (e.g. by convincing his son to come on the trip with a broken forearm), was accused for being too critical and authoritarian. The viewers frankly expressed their concerns that 'children with such fathers are likely to either become a tyrannic [sic] criminal or become too timid' (Zhihu user). In contrast, Zhang Liang's relaxed, unassuming demeanour and his 'democratic,' 'cool,' 'bro-like' style of parenting was well received. In Episode Two, Zhang's six-year-old son was resistant to participating in a task and thus refused to join the others. Later at bedtime, Zhang used a clever role play which puts his son in other people's shoes to teach him to be more considerate to others. In other episodes, Zhang also demonstrated genuine respect and trust for his son by talking to him in an adult-to-adult fashion and by supporting his (sometimes not so wise) choices unconditionally. Zhang's parenting techniques were widely applauded by viewers who 'very much appreciate his way of treating his child as his equal,' as one viewer wrote in an online comment.

-

Nevertheless, reservations on the 'nice' parenting style were strong. Participating fathers, through discussion, came to the consensus that 'one has to be strict with the child when necessary, but also affectionate with the child when necessary' (Episode Six), thereby underlining a balanced combination of warmth and control. Even Zhang, who expressed his aspiration to be 'lifelong bro' of his son, commented that 'as a father you not only have to let your child know that you are his friend, but you need to let him know that you are a parent too.'

-

More interesting, however, is how the desirable fathering behaviour varies by the gender of the child. Although the contrast of father-son and father-daughter dyads were not made evident by the production team, the audience readily evaluated the fathers' parenting behaviour through the lens of gender, which is exemplified by the viewers' comments on actor Guo Tao and artist and race-car driver Lin Chih-Ying. Speaking a soft Taiwanese accent, Lin always lowered himself when talking to his four-year-old son, and used patience, reasoning and tolerance when his son was afraid or distressed. Lin and his son's interactions, filled with prolonged cuddling and child-directed language, was charged with tenderness and intimacy. Guo, a Beijing local, preferred to show his affection through action rather than words. Guo and his son's playtime was characterised by rough-and-tumble play, running and chasing, and slightly vulgar jokes. While Lin was praised for his gentility, many pointed out that he was 'too soft…and is not decisive or manly,' and that 'his child would become weak and wilful and end up being a big trouble' (Douban users). Guo, despite the criticism about his harshness, was cheered by many as the proper trainer for 'real men' (chún yémenr). Actually, Lin himself found it 'good to let [my son] have a taste of Guo's 'manly' parenting style. Maybe he would learn more about courage.' Among fathers with girls, on the other hand, there was no such controversy: Although the two participating fathers, Tian Liang and Wang Yuelun, diverged considerably in their parenting practices, neither the production team nor the viewers linked their parenting behaviour to their daughters' gender development.

-

The quotes above show how the 'globalised,' child-centred fathering approach has considerably revised the 'traditional,' hierarchical father-child relations, indicating diminishing patriarchal values along the intergenerational axis at least among the urban elite fathers. While existing studies have highlighted Chinese parents' inner conflicts between their children's well-being (i.e. concurrent happiness) and well-becoming (i.e. future self-sufficiency and success in the competitive labour market),[55] the participating fathers of this reality programme were determined to prioritise the former, presumably due to their children's young age and their own affluent financial status. This new parenting model, however, was challenged by the disapproval of 'soft' fathering of boys (but not of girls). Such clash resonates with the argument that masculinity (but not femininity) needs to be deliberately built and explicitly performed.[56] The expectation of fathers to be 'tough' and 'manly' to their sons is also a manifestation of the greater anxiety about the future of Chinese males and masculinities which now appear to be under crisis: On the one hand, the competitive market economy, which requires bravery, toughness and confidence, rejects the gentility and emotional reservation that used to be the core characteristics of Chinese masculinity ideals; on the other hand, the superficial 'rise of the feminine and the decline of the masculine' (yīnshèngyángshuāi)57 in today's China poses threats to the patriarchal gender order. These seemingly clashing socialisation goals of fathers reflect the different rates of change along the intergenerational and gender dimensions of Chinese patriarchy, with the lingering male superiority slowing down the change of fathering norms for fathers of sons.

Conclusion

-

In this current study I present an up-to-date analysis on the changing construction of fatherhood in contemporary China through a close-up examination of the popular reality show Dad, where are we going?. The analysis of the production and reception of this programme demonstrated that the acknowledgment of men's 'innate' desire to bear offspring and devotion to childrearing (i.e. 'paternal instinct'), the wish for increased paternal involvement in childcare, and the preference for a liberal, emotionally warm fathering style over the critical, authoritarian stance (although more so for girls than for boys), are central components of contemporary urban Chinese fatherhood, as reflected in the reality show. Taken together, these changes point to profound shifts in fathering norms in contemporary China—shifts which are likely to stem from China's socioeconomic and cultural transformations throughout the twentieth century. In the globalised, market-oriented, singleton-dominated China, the parent-child relationship departs from a patriarchal institution that favours power and dominance of older generations and moves towards increasing child-centredness, although the adult perspective is still used as the orthodox frame of reference for parental norms. At the same time, however, the transformation of gender relations is much less pronounced. True, that rigid adherence to the hands-off, emotionally distant fathering model is diminishing, as seen in the viewers' endorsement of the highly involved, caregiving 'nursing dad.' However, the acquiescence of an unequal division of childcare work, and the anxiety about nurturing the 'real men' in the next generation, hint at a (camouflaged) wish to uphold male dominance over the female. The contrast between the radical changes in parent-child relations and the (albeit implicit) conservativeness in gender hierarchy resonates with Shen's ethnographic study in Shanghai families,[58] and reveals how fatherhood and manhood can take intertwined yet independent evolutionary courses in China's modernising, globalising process.

-

This article is only the beginning of a growing body of research on Chinese men as parents and their parenting ideologies and behaviour, and more research is needed. For instance, Dad, where are we going? has singled out the father-child dyad from the web of family relations and has removed father-child interactions from everyday life. Examinations of fathering strategies and practices with the presence and/or in conjunction with the child's mother in day-to-day childrearing would further contribute to the understanding of fatherhood culture in contemporary China. Due to the limited space, I have focused on the behaviour of celebrity fathers whose masculine identity is secured in the institution of hegemonic masculinity through their professional success and the consequent high ability to provide for their families as main breadwinners. While these fathers do encounter challenging situations that parents and children typically experience in everyday life, they are likely to have different parenting values, priorities and concerns from fathers in the general Chinese population. The 'culture of fatherhood' among these (relatively) young, affluent, and educated fathers, which revolves around parental investment, close engagement and emotional intimacy, might not be the ideal observed by fathers in less privileged conditions. This gap has been repeatedly found among parents across social classes both within and beyond China.[59] As one viewer wrote with deep suspicion, 'I doubt whether rural viewers can learn much from this programme.' Studies of fatherhood ideals among underrepresented social groups, for instance through a reading of another reality show X-Change—which highlights the urban-rural contrast in children's developmental trajectories by adopting a 'swapping' format[60]—would provide valuable insights into the social stratification of parenting ideologies and practices. This line of research could further benefit from the juxtaposition of Chinese fatherhood with fathering values, practices and discourses in societies that bear similar socioeconomic and cultural specificities as China, such as other fast developing countries and other societies under the influence of Confucianism. Such a comparative perspective would help disentangle the various influences and highlight the dynamic tension between global and local cultures in shaping norms and practices of fatherhood.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Lamb, William Jankowiak, Ronald Rohner, Steve Harrell, Goncalo Santos, and Kam Louie for their insights on fatherhood and Chinese masculinities. I also thank Qiong Xu and Heyi Zhang for all the inspirational discussions throughout the production of this article.

Notes

[1] Kam Louie, Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[2] Bret Hinsch, Masculinities in Chinese History, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013.

[3] Derek Hird, 'White-collar men and masculinities in contemporary urban China,' Ph.D. dissertation, University of Westminster, 2009.

[4] Geng Song. 'Chinese masculinities revisited: Male images in contemporary television drama serials,' Modern China 36(4) (2010): 404–434.

[5] John Osburg, Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China's New Rich, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013.

[6] Song, 'Chinese masculinities revisited,' p. 416.

[7] Osburg, 'Anxious wealth,' p. 143.

[8] Harriet Evans, The Subject of Gender: Daughters and Mothers in Urban China, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

[9] Amidst the overall dearth of empirical research on Chinese fathers, the following chapters contain fragmental records of Chinese fathers in early 1970s and early 1980s. Margery Wolf, 'Child training and the Chinese family,' in Anthropological Realities: Readings in the Science of Culture, ed. Jeanne Guillemin, pp. 123–38, . New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Inc., 1970; William Jankowiak, 'Father-child relations in urban China,' in Father-Child Relations: Cultural and Biosocial Contexts, ed. Barry S. Hewlett, pp. 345–63, New York: Walter de Guyter, 1992. The following reviews are some of the rare summaries of the (very limited) empirial evidence on Chinese fathers: David Y.F. Ho, 'Fatherhood in Chinese culture,' in The Father's Role: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, ed. Michael E. Lamb, pp. 227–46, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987; David Shwalb, Jun Nakazawa, Toshiya Yamamoto and Jung-Hwan Hyun, 'Fathering in Japan, China and Korea,' in The Role of the Father in Child Development, ed. Michael E. Lamb, pp. 341–87, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2010; Xuan Li and Michael E. Lamb, 'Fathers in Chinese culture: Traditions and transitions,' in Fathers across Cultures: The Importance, Roles, and Diverse Practices of Dads, ed. Jaipaul Roopnarine, pp. 273–306, New York: Praeger, 2015.

[10] Steve Harrell and Goncalo Santos, 'Introduction,' in Transformations of Chinese Patriarchy. Contemporary Anthropological Perspectives, ed. Steve Harrell and Goncalo ???, University of Washington Press, in press.

[11] Yifei Shen, 'China in the "post-patriarchal era": Changes in the power relationships in urban households and an analysis of the course of gender inequality in society,' in Chinese Sociology & Anthropology 43(4) (2011): 5–23.

[12] Nadine M. Tang, 'Some psychoanalytic implications of Chinese philosophy and child-rearing practices,' The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 47 (1992): 371–89.

[13] For the respective roles of Chinese fathers and mothers see two excellent reviews: Ruth Chao and Vivian Tseng, 'Parenting of Asians,' in Handbook of Parenting, ed. M.H. Bornstein, pp 59–84, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002; Su Yeong Kim and Vivian Y. Wong, 'Assessing Asian and Asian American parenting: A review of the literature,' in Asian American Mental Health: Assessment Methods and Theories, ed. Karen Kurasaki, Sumie Okazaki and Stanley Sue, pp. 185–201, New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002.

[14] David Y.F. Ho, 'Continuity and variation in Chinese patterns of socialization,' Journal of Marriage and Family 51(1) (1989): 149–63.

[15] See Lŭ Xùn's 1919 essay What is Required of us as Fathers Today?. For English translation see Xianyi Yang and Gladys Yang (eds), Lu Xun Selected Works, Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1980.

[16] Lŭ Xùn, What is Required of us as Fathers Today?

[17] Lee C. Lee, 'Daycare in the People's Republic of China,' in Child care in Context: Cross-cultural Perspectives, ed. Michael Lamb, Kathleen Sternberg, Carl-Philipp Hwang and Anders Broberg, pp. 355–94, Hillsdale, NJ: Psychology Press, 1992.

[18] Novikova Irina, 'Fatherhood and masculinity in postsocialist contexts – Lost in translation?' in Fatherhood in Late Modernity: Cultural Images, Social Practices, Structural Frames, ed Mechtild Oechsle, Ursula Müller and Sabine Hess, pp.95–112, Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2012.

[19] Hanna Nielsen, 'The three father figures in Tian Zhuangzhuangs film The Blue Kite: The emasculation of males by the Communist Party,' in China Information 8(4) (1999): 83–96.

[20] Song, 'Chinese masculinities revisited', p. 406

[21] On the contrary, women were encouraged to actively participate in childbearing, with honorary titles given to women with multiple childbirths.

[22] Xiaoyuan Shang, Xiaoming Wu and Yue Wu, 'Welfare provision for vulnerable children: The missing role of the state,' The China Quarterly, 181 (2005): 122–36.

[23] Yanxia Zhang and Mavis Maclean, 'Rolling back of the state in child care? Evidence from urban China,' International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 32(11/12) (2012): 664–81.

[24] Osburg, Anxious Wealth, pp. 37–75.

[25] Karita Kan, 'The new "lost generation": Inequality and discontent among Chinese youth,' China Perspectives 2 (2013): 67–73.

[26] Esther Goh, China's One-child Policy and Multiple Caregiving: Raising Little Suns in Xiamen, London: Routledge, 2011; Ying Wang and Vanessa L. Fong, 'Little Emperors and the 4:2:1 Generation: China's singletons,' Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 48(12)(2009): 1137–139>. For changes in gender dynamics, see Willian Jankowiak and Xuan Li, 'The decline of the chauvinistic model of Chinese masculinity,' Chinese Sociological Review 46(4) (2014):3–18.

[27] This term is first coined by Viviana Zelizer. See Viviana A. Rotman Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

[28] Vanessa L. Fong, Only Hope: Coming of Age under China's One-child Policy, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

[29] Xuan Li and William Jankowiak, 'The Chinese father: Masculinity, conjugal love, and parenting,' in: Changing Chinese Masculinities: From Imperial Pillars of State to Global Real Men, ed. Kam Louie, pp. 186–203, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016.

[30] Growing Pains, Neal Marlens (Producer), ABC, New York, 24 September 1985.

[31] See Amy Chua, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011 and Baiyou Xiao, So all my Children went to Peking University, Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian Culture Publishing House, 2011.

[32] Annette Hill, Reality TV: Audiences and Popular Factual Television, Oxon: Psychology Press, 2005, p. 2.

[33] Hill, Reality TV, pp. 14–40.

[34] All age figures and sibling status here refer to the age and sibling status at the time of show production.

[35] '爸爸去哪兒 (第一季)' (Where Are We Going Dad (Season 1)), Wikipedia, December 2013 (accessed 19 May 2016).

[36] The present article is limited to the analysis of Season One, since the father-child interactions and group dynamics were complicated by child and father age, number of children from each father, and linguistic diversity among the participants in later seasons.

[37] Hill, Reality TV, p. 108.

[38] Michael E. Lamb, 'The history of research on father involvement,' Marriage & Family Review 29(2/3) (2000): 23–42.

[39] For studies on the associations between paternal involvement and spousal (i.e. maternal) support see: Sarah M. Allen and Alan J. Hawkins, 'Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers' beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work,' Journal of Marriage and Family 61(1) (1999): 199–212; Mar F. DeLuccie, 'Mothers as gatekeepers: A model of maternal mediators of father involvement,' Journal of Genetic Psychology 156(1) (1995): 115–31; and Chih-Yuan S. Lee and William J. Doherty, 'Marital satisfaction and father involvement during the transition to parenthood,' Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers 5(2) (2007): 75–96.

[40] See Ho, 'Fathers in Chinese culture,' pp. 227–46; Shwalb, Nakazawa, Yamamoto and Hyun, 'Fathering in Japan, China and Korea,' pp. 341–87.

[41] Susan Brownell and Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, Chinese Femininities, Chinese Masculinities: A Reader, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

[42] Susan Greenhalgh, '"Bare sticks" and other dangers to the social body: Assembling fatherhood in China,' in Globalized Fatherhood, ed. Marcia C. Inhorn, Wendy Chavkin and José-Alberto Navarro, pp. 359–81, New York: Berghahn Books, 2014, p. 360.

[43] William Jankowiak, 'Father-child relations in urban China,' in Father-Child Relations: Cultural and Biosocial Contexts, ed. Barry S. Hewlett, pp. 245–63, New York: Walter de Guyter, 1992.

[44] Xuan Li, 'Paternal affection display in contemporary Chinese families,' Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cambridge, 2015.

[45] Judith Phillips, Care, London: Polity, 2007.

[46] Berit Brandth and Elin Kvande, 'Masculinity and child care: The reconstruction of fathering,' Sociological Review 46(2) (1998): 293–13.

[47] Xiaodong Lin, '"Filial son", the family and identity formation among male migrant workers in urban China,' Gender, Place & Culture 21(6) (2014): 717–32

[48] Ralph LaRossa, Charles Jaret, Malati Gadgil and G. Robert Wynn, 'The changing culture of fatherhood in comic - strip families: A six-decade analysis', Journal of Marriage and Family 62(2) (2000): 375–87.

[49] See: Esther Dermott, Intimate Fatherhood: A Sociological Analysis, Oxford: Routledge, 2008; Lamb, 'The history of research on father involvement,' pp. 23–42.

[50] See the following reviews: Xinyin Chen, Yufang Bian, Tao Xin, Li Wang and Rainer K. Silbereisen, 'Perceived social change and childrearing attitudes in China,' European Psychologist 15(4) (2010): 260–70; Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Niobe Way and Xinyin Chen, 'Large-scale economic change and youth development: The case of urban China,' New Direction of Youth Development 135 (2012): 39–55.

[51] Niobe Way, Sumie Okazaki, Jing Zhao, Joanna J. Kim, Xinyin Chen, Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Yueming Jia and Huihua Deng, 'Social and emotional parenting: Mothering in a changing Chinese society,' Asian American Journal of Psychology 4(1) (2013): 61–70.

[52] Orna Naftali, Children, Rights and Modernity in China: Raising Self-governing Citizens, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[53] Qiong Xu and Margaret O'Brien, 'Fathers and teenage daughters in Shanghai: Intimacy, gender and care,' Journal of Family Studies 20(3): (2014): 311–22.

[54] Li, Paternal affection display in contemporary Chinese families, pp.58–114.

[55] See Fong, Only Hope; and Naftali, Children, Rights and Modernity in China.

[56] Hinsch, Masculinities in Chinese History, pp. 29–31.

[57] Kam Louie, 'The macho eunuch: The politics of masculinity in Jia Pingwa's "human extremities",' Modern China 17(2) (1991): 163–87, p. 166.

[58] Shen, 'China in the "post-patriarchal era".'

[59] Yudan Chen Wang, 'In search of the Confucian family: Interviews with parents and their middle school children in Guangzhou, China,' Journal of Adolescent Research 29(6) (2014): 765–82.

[60] This format is present in British and American reality programmes Trading Spouse and Wife Swao, in which two families, usually from drastically different social strata, exchange spouses for a short period of time.

|