Intergenerational Reciprocity Reconsidered:

The Honour and Burden of Grandparenting in Urban China

Esther C.L. Goh, Bill Y.P. Tsang and Srinivasan Chokkanathan

Introduction

- Increasing life expectancy, coupled with an unprecedented decline in fertility, has spawned a substantial body of research relating to population ageing and the nature of elder care provided within families.[1] This research however, captures only a portion of the care-related issues that involve older Chinese and their families. After all, older persons are not only receivers of care. The invaluable contributions made by grandparents, especially grandmothers, to their families by caring for grandchildren in Asia are less explored yet equally important.[2] Chinese grandparents in particular are integral partners in raising children[3] while also providing important contributions to their adult children's household like meal preparation and house cleaning.[4] Yet it is only in recent years that the subject has attracted the attention of the research community. A survey of extant studies shows that researchers tend to frame grandparent provision of care as part of an intergenerational exchange with adult children.[5] Only a few studies attend to grandparents as care providers.[6] At the core of many of the extant studies of intergenerational exchange in Chinese families is the concept of reciprocity. Reciprocity has been utilised by scholars studying this context because of its intuitive relationship to the Confucian value of filial piety that governed family relationships in China for thousands of years. In the Confucian system both the roles and the duties of family members are connected through mutual interdependence over the course of the life cycle.[7] Rather than considering grandparenting as an extra burden or chore, the literature depicts Chinese grandparents as likely to think of caregiving as a way to 'enjoy family happiness' and as something that is willingly exchanged for the help they receive from their children. Studies have reported positive benefits of improved mutual communication and understanding, closer emotional ties, and increased sense of mutual dependence between the generations[8] as well as enhanced health for the grandparents[9] who play the role of caregivers to their adult children's households.

-

This harmonious picture contradicts an older literature, where intergenerational conflicts in traditional extended Chinese families are well-documented, especially those between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law.[10] But, little research attention has been paid to the 'conflict face'[11] of relationships between older parents and their adult children in contemporary China. In this paper we address two important but under-studied questions. First, what contributes to the positive and/or negative relational dynamics between the generations when older parents reside under the same roof while caring for their only grandchild? Second, what sustains grandparents in providing childcare and housework assistance to their adult children's households? Logic dictates that relationships are unlikely to be conflict-free when grandparents reside in their adult children's house to help care for their grandchildren and provide much needed domestic help to the household. Although grandparents have long provided informal care for their grandchildren, even in the traditional extended family,[12] the earlier scenario was very different. Grandparents then, especially grandmothers, were regarded as the final authority and expert on raising children.[13] Theirs was the position of power and esteem in the extended family structure. As family power centre has shifted from old to the young,[14] grandparents no longer enjoy the power and status their traditional counterparts once did.

Grandparents as caregivers and shifting norms of filial piety

-

As we are at a juncture where norms of filial piety are shifting in the face of modernisation, industrialisation and rapid economic growth, studying grandparents as caregivers offers an important opportunity to re-examine families. Although families are still the primary source of old age care, the unique structural features that supported filial piety—patriarchal families, the family-centric economy and the collective dependence of members on the extended family—are disappearing.[15] New research[16] has shown that the rise of individualism[17] has been accompanied by an erosion of filial responsibilities among adult children who would traditionally be responsible for caring for their older parents. Likewise, elders in urban China[18] are less financially dependent on their adult children; many have their own pensions and subsidised medical care. But this is not the way many of these older persons were raised, and despite (or because of) the shifting norms in the practice of filial piety, some feel the need to use strategies to nurture a sense of filial obligation in their adult children and maintain emotional bonds with them. One way of doing so is by providing childcare for their children.[19]

-

As in many developed countries, Chinese families have become more affluent, and with fewer children in each household the primary value of each child has shifted from economic to emotional.[20] This shift has led family members, including grandparents, to focus their resources on ensuring that the 'only child' receives the best possible care.[21] The cost of providing the best possible care can be a financial burden for families,[22] one that can only be alleviated if both parents are working outside the home. In view of the lack of childcare facilities,[23] especially after-school care, and wide-spread mistrust towards domestic helpers,[24] parents find it easy to insist that the best person to care for their only child is the grandparent. And because Chinese grandparents tend to consider the welfare of the family before their own interests[25] they are often willing to compromise their own lives to help their children. Also, it is common for Chinese adult children, even after forming their own nuclear family unit, to continue their membership in their parental family. The extended family household is viewed as a common enterprise[26] where members from both generations (older parents and adult children) have a vested interest to ensure chuang zong jie dai (pass on the family line).[27] According to the Chinese sociologist Li Yinhe,[28] the Chinese grandparents invest themselves in their children not only for support in old age but even more for the continuity of the family line. This is not a mere extension of one's life, but to ensure the passing down of the family lineage. Thus, grandparents sacrifice themselves for their children because they are driven by this cultural ideal. For the same reason, she asserts, adult children do not feel a sense of shame or guilt in requesting financial or other forms of help from their older parents. Grandparents may or may not receive rewards in return for help rendered, as the supreme importance placed on families to pass on the family line allows adult children to invest in their children (i.e. grandchildren) as a form of repayment to their older parents.[29]

-

This familial tension in caring responsibilities between the grandparents' generation and their adult children is situated in the changing social, cultural and economic context of the country. For more than three decades, rapid urbanisation, economic development and state regulated family planning have disrupted the traditional practice of filial piety and value of intergenerational harmony. In recognition of the rising risk of elderly being exploited and uncared for by the younger generation, the Chinese government has been promoting the vision of a Harmonious Society in the past ten years, boosting social security, health and community services for the elderly, in providing more formal support for them in addition to the filial obligations from their children.[30] But challenges remain. Since the mid-1980s, the government has attempted to institutionalise family support for the elderly through jiating shanyang xieyi (Family Support Agreement (FSA)), which is a voluntary contract between older parents and adult children on providing support to parents.[31] However, the success of FSA is uncertain as there are many operational difficulties in enforcing the agreement, and institutionalising familial support that inherently, entwined with close relationships, counters the fundamental value and assumptions of filial piety. Familial relationships cannot be based on contracts or agreements alone, rather more on mutual trust, emotional bonding and unspoken expectations.

-

To answer the two research questions, in this paper we utilise a framework based on 'symbolic or communicative value,'[32] and the significance of 'regard'[33] in reciprocity as a lens of inquiry into the mechanism that influences the experiences of caregiving by grandparents. Methodologically, it is our belief that survey measures employed in the extant studies mentioned above were not effective in capturing the full range of relational dynamics. Instead, we employed mixed methods of survey and ethnography, to illuminate these subtle emotional nuances between generations.

Conceptualising reciprocity

-

According to Linda Molm,[34] all forms of social exchange occur within structures of mutual dependence. An exchange can be either direct (an immediate exchange between two actors) or indirect (the recipient of the benefit does not return the benefit directly to the giver but to another actor in the social circle). Family exchanges are typically non-negotiated forms of both direct and indirect reciprocity. Molm posits that the different structures of reciprocity have important implications for the bonds between the exchange partners through four mechanisms:35 1) trust (the belief that exchange partners will not exploit one another); 2) affective regard (mutual positive feelings for and evaluations of the exchange partner); 3) relational solidarity (perception of the relationship between exchange partners as a single social unit with actors united in purpose and interest); and 4) interactional fairness (perceptions of fair interpersonal treatment between exchange partners).

-

Molm argues that the structure of reciprocity affects the quality of bonds through three causal mechanisms: the structural risk of non-reciprocity, the expressive value of voluntary acts of reciprocity, and the relative salience of the cooperative or conflict 'faces' of exchange. In the case of structural risk of non-reciprocity, risk is linked to the development of trust in the relations between giver and recipient. When an actor has both the incentive and opportunity to exploit another actor but acted benignly, then trust is established between the two. The expressive value of voluntary acts of reciprocity can be defined as the symbolic or communicative value attached to the act of reciprocity itself over and above any instrumental value produced by the exchange partner's reciprocity. As such, it communicates regard for the partner and the relationship,[36] acknowledging and conveying appreciation for benefits received as well as enhancing feelings of relational solidarity and perceptions of interactional fairness. Finally, she points to the relative salience of the cooperative or conflict 'faces' of exchange, where the greater the relative salience of the conflictual aspect of exchange, the weaker the bonds that develop will be.

-

In this framework, two types of emotion arise from the causal mechanisms and have direct influence on the bonds of the exchange partners. In a context of risk, a voluntary, reciprocal act communicates regard for the exchange partner and the willingness to invest in the relationship. Receiving another's expression of regard and relationship investment should prompt positive emotions of pleasure and satisfaction which in turn enhance trust and promote the perception of fair dealings by the recipient. Displeasure, on the other hand, arises when conflictual aspects of exchange become salient and actors are likely to perceive exchange partners as unfair. The severity of felt injustices increases the likelihood that disadvantaged actors will protest or take action to restore equity.

-

From an anthropological perspective, acts of reciprocity are culturally embedded. In this case, it is important to reflect on how Molm's framework on social exchanges intersects with the Chinese concept of guanxi (relationship). The meaning of guanxi is highly dependent on the people and context involved. There are direct as well as indirect elements in guanxi. As in Molm's structures of reciprocity, relationships are established with mechanisms of feelings or ganqing, and human obligations or renqing which is closely tied to reciprocity in social interactions.[37] The concept of 'face' is central in the social exchange mechanism that expresses honour or respect to the other. This is often connected to gift giving and exchange of favours.[38] In the context of intergenerational relations in the family, this involves more non-negotiated exchanges. In the relationship between older parents and their adult children, face can be subtle and nuanced, especially in the reciprocal acts of filial piety from children to parents. Despite the fast changing social landscape in China and shifting demographics in its rural and urban development, guanxi remains an important concept in understanding familial relations[39] and shall be taken into consideration in our discussion.

Data and analytical approach

-

In this paper we combine data from a survey of parents of children who attended thirty-nine different primary schools (N=1627) in Xiamen with participant-observation data from five three-generation families over a period of six months. Data was collected from the intimate interactions and interviews with all the grandchildren (N=6), adult children (N=8) and older parents (N=8) of five three-generation-under-one roof family units. Data which stemmed from interviews with grandchildren is however, not included in the analysis of this paper owing to space constraints. It is worth noting that our analysis illustrates ways in which qualitative data can be used to access nuances of behaviour that are not available in our quantitative findings and so brings to the fore deeper insights into relationship dynamics in three-generation families.

Family Survey

-

Participants. This paper draws in part from a larger survey undertaken by Esther Goh. The survey involved a non-random sample drawn from thirty-nine primary schools located in two zones of Xiamen Island that was conducted in December 2006 and January 2007.[40] The age range of the students involved in the survey was between six and twelve years. A total of 1743 questionnaires was distributed and 1657 were returned. The response rate was about 95 per cent. After invalid and suspicious forms were excluded the total sample was 1627.

-

Instrument. A thirty-item questionnaire was designed to collect demographic data on the families as well as the collaboration between parents and grandparents as joint caregivers. The items were all closed questions with a nominal scale. The questions addressed: demographic profiles including age, income and gender of the various generations (nine items); living arrangements and childcare provided by grandparents (five items); role division between grandparents and parents (four items); past and the anticipated future duration of care by grandparents (two items), advantages and disadvantages of the collaborations (six items); and the relationships between the 'only-children' and their caregivers (three items). Finally two items concerned parents' perception of grandparents' help as voluntary or obligatory, and the types of rewards they gave to grandparents for helping with childcare.

-

Procedures. Teachers from the thirty-nine participating primary schools distributed the questionnaires to their students who took them home for their parents to complete. After the teachers collected the forms from the students, a research assistant went to the thirty-nine schools to check and collect the forms. All the valid questionnaires were coded, and two paid persons helped to key in the data. Cross auditing was performed to check for possible errors in data entry.

Ethnography of Five Families

-

Goh (the researcher) made two field visits to Xiamen and conducted pilot studies in 2004 and 2005. To collect in-depth ethnographic data, she stayed in the field and followed five families over six months from March to September 2006.

-

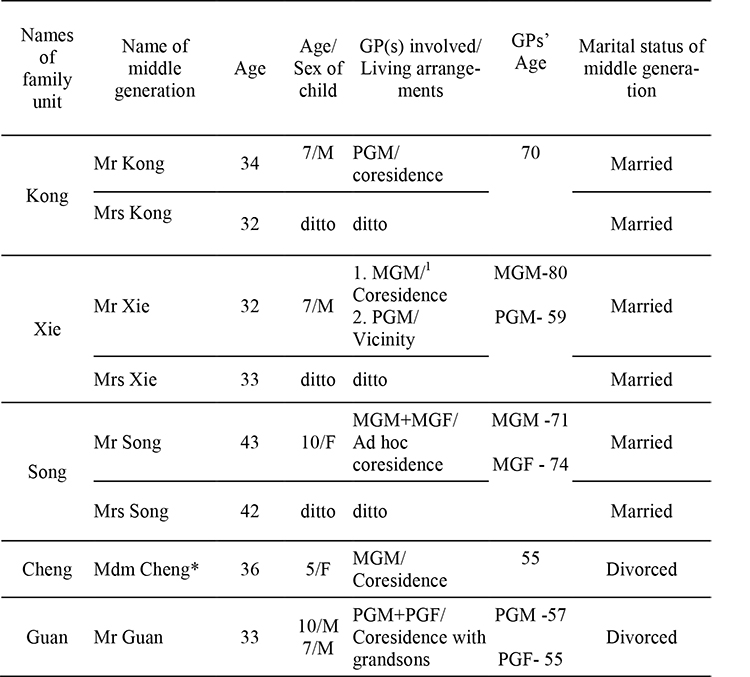

Recruitment of five participating families. The criteria for selecting five families for intensive participant observation and interviewing were keyed to the various types of grandparental involvement in providing childcare found in the family survey. These variations included lineage and living arrangements. In the Kong family, the paternal grandmother co-resided under the same roof to take care of the grandson and provide help with housework. This case corresponded to the survey results which showed that 49 per cent of paternal grandmothers caring for grandchildren and assisting in housework on their own (without paternal grandfathers) co-resided in three-generation families. The Xie family had grandmothers from both sides of the lineage helping with childcare and housework. One of the grandmothers co-resided with the family while the other stayed close by. This type of arrangement matched 58 per cent of the surveyed households where both grandmothers were providing childcare and housework assistance to their adult children. In the Song family both maternal grandparents co-resided with the family periodically to provide childcare and perform housework on an ad hoc basis. The survey found that 17 per cent of maternal grandparents were involved in this way. The Cheng family had only a maternal grandmother co-residing to provide long-term childcare and help in housework. This living arrangement was consistent with 31 per cent of those surveyed. This family is somewhat different from the first three families because the adult daughter was recently divorced. The Guan family was a migrant family where paternal grandparents acted as informal custodial parents to their two grandsons. Their adult son had divorced three years earlier and could not afford to care for the two boys. The case was included as an outlier or deviant sample[41] to contrast with the other cases since this is the only family where an adult son was only marginally involved in caring for the children.

-

On average, thirteen visits/contacts lasting sixty-ninety minutes each were made with each family over the six month period. After each contact the researcher logged a contact summary which recorded the nature of the encounter and salient points of observation.

-

Analytical strategies for ethnographic data. The field notes and memos collected over the six months, together with the transcripts of interviews with all the members of the five participating families, were analysed carefully by first reading them through thoroughly several times. The data regarding interactions across adult children and their older parents were categorised with the aid of the qualitative software Nvivo.

-

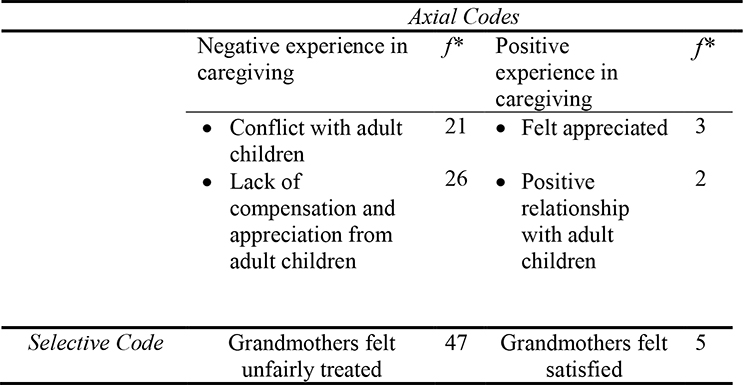

Our interest in understanding the subtle emotional nuances experienced by grandparents led us to create as many open codes as were required to capture the slight differences in meaning that emerged from the data. A total of forty-seven open codes were created to capture the negative aspects of grandparents' helping experience, and five open codes for positive emotional nuances. The emerging similarities were checked and adjusted by rereading the data. The second phase of coding, axial coding, involved a process of relating codes (categories and properties) to each other, using a recursive process of inductive and deductive inference known as constant comparison.[42] It became apparent that negative open codes outweighed positive ones (refer to Appendix 1 for details). Selective coding was the final phase of the analytic process, and we used it to integrate and refine central themes.[43] Three axial codes namely: conflict episodes with adult children; lack of expression of appreciation (tangible or intangible) from adult children; and felt treated like domestic helpers by adult children were subsumed under the selective code of 'taken for granted.' While two axial codes namely: felt appreciated and positive relationships with adult children were subsumed under the select code of 'satisfied.' Attention was paid to contradictory data in order to avoid selective analysis and presentation of data where one finds what one wishes to find. In addition, paying attention to contradictory data served to illuminate the different viewpoints of the adult children and their older parents and unpack the dialectical nature of intergenerational interactions.

Findings

-

Out of the 1627 surveyed, almost half (N=738) of the adult children had grandparents rendering assistance in housework and childcare. The survey shows grandparents have strong commitment to supporting their adult children's households by providing different types of domestic services over a long period. The findings also reveal that slightly more than half of the adult children did not often reciprocate for services received.

Grandparents' commitment in helping adult children

-

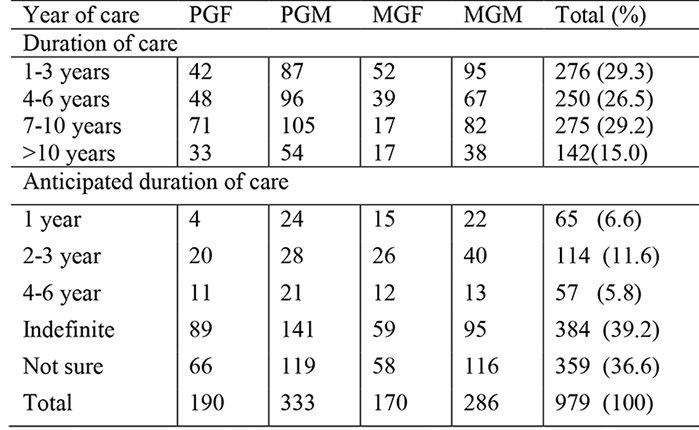

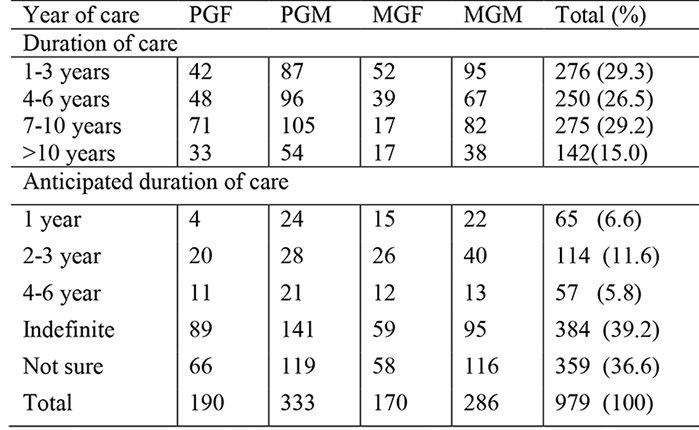

Most of the grandparents that helped tended to do so for a long period of time. About 44 per cent of them had helped for between seven to ten years or more. Another 26 per cent of them had helped for between four and less than six years and the rest (30 per cent) between one and three years. On anticipated duration of care, 39 per cent of the respondents stated that the grandparents would be extending their services indefinitely, 36 per cent of them were not sure and another 17.4 per cent of them had stated between two and six years. Regardless of duration of care, it is evident that paternal grandparents are involved more often (N=536) than maternal grandparents (N=407), and that grandmothers are twice as involved in care (N=624) as grandfathers (N=319). This suggests that grandparenting is a gendered endeavour, both in terms of who provides grandparental care (grandmother/grandfather), and whether it is provided through the matriline or the patriline (maternal or paternal grandparents).

|

Note: PGF=Paternal Grandfather; PGM=Paternal Grandmother;

MGF=Maternal Grandmother; MGM=Maternal Grandmother

Table 1. Duration of Care

Childcare and housework load distribution between parents and grandparents

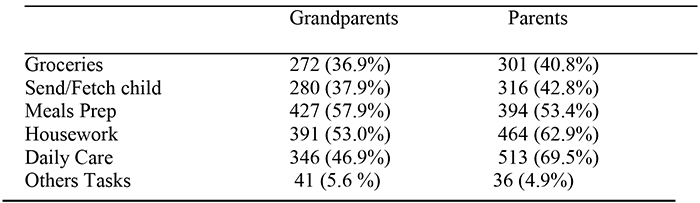

Among the 738 parents who had grandparents helping, more than half reported that the grandparents prepare meals and do the housework. Additionally, slightly more than one-third of the parents had also stated that the grandparents do groceries, send and fetch children from school and slightly less than half of them had reported that the grandparents contribute to daily care of the children. Furthermore when similar questions were asked about their own contribution, around two-thirds of the parents stated that they carried out household chores and daily care of the children. With regards to grocery shopping and sending/fetching children, there seems not to be much difference between parents' and grandparents' load.

Note. Percentage exceeds 100 due to multiple responses.

This survey assessed division of housework load between the two generations only from the perspective of the middle generation.

Table 2. Distribution of Housework Load between Parents and Grandparents (n =738)

Although the results show little difference in the frequency of housework performed by parents and grandparents, we have to understand that grandparents are in fact significantly lowering the burden of parents by taking on housework, meal preparation and childcare. Some caution should be exercised in reading these results as they were self-reported by the adult children. It is a possiblity that they over reported their own contribution while underreporting that of the grandparents. Our sense of caution arises from observing grandparents doing the lion's share of housework and childcare duties during the ethnographic phase of our research.

Half of the middle generation did not reciprocate for services received

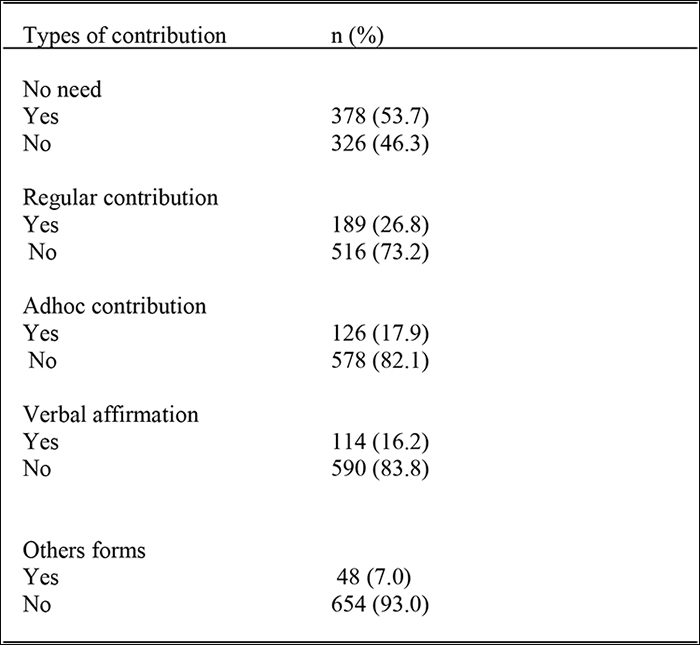

Considering the substantial amount of services adult children received from their older parents, it is noteworthy that their acts of reciprocity hardly matched the grandparents' level of giving.

* n < 738 due to missing values

Table 3. Adult Children's Opinion on Contributing back to Grandparents

When asked in what ways they would express their gratitude to their older parents when rewarding them, slightly more than half of them (53.7 per cent) said there is 'no need' because grandparents are part of the family. About one quarter of the adult children (26.8 per cent) said they made regular monetary contributions to their parents. An even smaller number made ad hoc monetary contributions (17.9 per cent) or used verbal affirmation (16.2 per cent) as forms of expressing their gratitude. To understand if the financial status of the grandparents affects adult children's tendency to reciprocate, we differentiate grandparents with and without pensions. A greater number of adult children wanted to give regular contributions to the grandparents without pensions (32.1 per cent) than to those with pensions (23.4 per cent), (χ2 = 5.68, d.f. = 1, p = .01). We also wanted to know if there is any income difference among the 53.7 per cent of adult children who said there was 'no need' to reciprocate. Statistical test results show no association between adult children's income and the attitude of 'no need' to reward. Hence, neither low nor high income played a part in influencing their general lack of reciprocity.

Findings from the ethnographic data will first present brief scenarios of how and why grandparents decided to render help in each of the five families to provide contextual understanding. Following that, main themes that surfaced pertaining to the presence or absence of regard by adult children to their older parents for services received and the resultant relational dynamics between the generations will be discussed. The detailed profiles of these five families can be seen in Table 4.

Note: GP=Grandparent; PGM=Paternal grandmother; PGF=Paternal grandfather; MGM=Maternal grandmother; MGF=Maternal grandfather.

* 'Madam' is a title unique in Chinese culture to address older woman regardless of their marital status. In Chinese the term is nu shi

Table 4. Profiles of five participating families

Grandparents providing services in five families

The Kong family. Paternal grandmother Kong, a sixty-nine-year-old retired accountant, was initially hesitant when her younger son requested her help with childcare. Both she and her husband had been caring for an older granddaughter since retirement, helping her younger son would mean she had to live apart from her husband. Despite her initial reluctance, Grandmother Kong convinced herself that she needed to lend support to the economic needs of the young family who were just starting out:

I thought to myself, this [burden] will certainly fall on me. So I came over to help. Engaging a domestic helper is very costly. Besides, they [son and daughter-in-law] are still paying the instalments [housing mortgag…so I should come over.

The Xie family. In this family, the eighty-year-old, widowed maternal grandmother resided under the same roof with her daughter, son-in-law and seven-year-old grandson. She was still active, healthy and mobile, and helped with meal preparation as well as supervising her grandson in his home work while the middle generation was at work. She explained the reason for coming to help: 'She [daughter] has no other solution. She has to work and there is no one to help her take care of the child. The boy was still so tiny, [and the] childcare centre is not ideal. She [daughter] said "Mum, please come over to give me a helping hand." So I came. As a mother I will do my best to help.' This eighty-year-old thought helping with housework actually kept her healthy. In the same family the fifty-nine-year-old paternal grandmother lived with her elder son's family within the same estate, where she helped to care for the twelve-year-old daughter, performed housework and doing meal preparation for the household. However, she also provided assistance to her younger son's child by walking the boy to and from school—eight trips every day[44]—so as to ensure his safety. These older women considered caring for grandchildren to be the best thing for them after retirement. The paternal grandmother had this to say, 'This is the way of life. If I don't do this, when I am old, maybe my son and grandchildren would also ignore me. What would I do then?'

The Song family. The maternal grandparents of the Song family are retired government officials who enjoy comfortable pensions. They have their own apartment in Nanping, about three hours bus ride away from Xiamen. They lead very active social lives, particularly since their retirement. Grandmother Song has many friends in her home town and often plays badminton and other games. Grandfather Song is a keen social dancer who frequently takes part in dance competitions. Both grandparents consider their adult daughter incapable of balancing work, childcare and housework. Also, they did not think very highly of their son-in-law's ability to care for the grandchild. To help their daughter, they come to stay with her periodically, alternating homes every three months.

When asked why they spent so much time helping their adult daughter, grandfather Song said, 'Chinese parents always put the welfare of their children first; we want to do something for the younger generations. Many grandparents are doing this. Some help for a shorter time, others help for a longer time.'

The Cheng family. Maternal grandmother Cheng, fifty-five years old, asked for early retirement at age fifty from her lower management job with a state-own factory after her granddaughter was born. She lived with her daughter and granddaughter to provide childcare, meals preparation and housework duties. Her daughter, Madam Cheng, had divorced a year earlier. When asked why she came to help with childcare, Grandmother Cheng gave two reasons, the main reason is because 'I feel xin teng (heartache) for my daughter. Also, in actual fact there is no more love [in my own marriage]. We [she and her husband] only live together as a routine.' After the daughter's divorce, Grandmother Cheng felt obligated to help with childcare because her daughter had no one else to whom she could turn. The child's paternal grandparents had cut all ties with the family. As such, Grandmother Cheng typified the Chinese parents' mentality of the 'self-imposed obligation' where she believed she could not abandon her adult daughter. One positive aspect of her caregiving role was that it provided an escape route from her strained marriage.

The Guan family.The last family studied was a migrant family from rural Sichuan province consisting of paternal grandparents raising their grandchildren. Their adult son, who was a migrant worker in Xiamen, had divorced three years earlier and turned to his parents to help with the care of his two sons, aged seven and ten. The younger Mr. Guan lived in a factory hostel, which could not take in the two boys. Upon the son's request, the grandparents Guan took on the role of surrogate parents instantly. Grandfather was a security guard with a meagre income. Grandmother Guan, illiterate, worked as a part-time cleaner.

This older couple was positive about their caregiving role. It was 'no big deal' for them to raise the two grandsons by themselves. The adult son visited them fortnightly and the mother of the two boys had left Xiamen after the divorce. Despite their lack of education, the grandparents had the clear goal of sending the ten year old to the top Tsinghua University in Beijing, and were diligently putting their savings into an educational fund towards this goal. The other equally important driving force behind this commitment was what grandfather termed qin qing (affinity of kinship). 'Grandfather taking care of grandson is a duty given by heaven.' This pair of grandparents treated the duty to fulfil cultural expectation as something positive.

Absence of regards

A sense of being exploited due to excessive workload, feelings of being unappreciated, and relationship strains appears to foster feelings of bitterness and displeasure and cast a negative shadow on experiences of grandparenting.

During the first visit in 2005, grandmother Kong complained that her daughter-in-law took her for granted and pushed all the household chores to her.

They were taking advantage of me when I first came to help. To be honest, I felt like a domestic helper. In actual fact my life here is exactly like a domestic helper. I should not feel this way because I am helping my own son and grandson. I stay with them, do everything for them, and they do nothing to help me. Another mother-in-law would have walked out.

This narrative, expressed in a guilty tone of voice, reflected Grandmother Kong's unhappy experience. She felt guilty because she thought she should altruistically and without complaint render help to this young family, her 'son and grandson.' Nevertheless, the feeling of being exploited, used and unappreciated was very real to her. She believed neither her son nor daughter-in-law appreciated how tough it was for her to shoulder all these responsibilities.

In Cheng's family, although the adult daughter Madam Cheng acknowledged that her mother had been a great help since the child's birth, she said that 'because my mother stayed with me and had free food and lodging, there is no need to give any monetary reward.' Regarding the sharing of housework, Madam Cheng said:

To be honest, there is no clear division of work. Of course I will not push everything to her and go out to enjoy myself. But I will let her do the simple tasks. I am lazy sometimes and let her do such chores as doing the dishes, so I hardly do it. But things concerning the child, I will do more.

Lack of conveyance of regard for help received

Many older adults felt the need to be appreciated for their effort rather than to be taken for granted. That is, they hope the middle generation would communicate regard by acknowledging and conveying appreciation for benefits received as well as putting in effort to enhancing feelings of relational solidarity and perceptions of interactional fairness. However, little of such regard was shown. Grandparents Song said the middle generation did not remember their birthdays and this was disappointing. When asked how the adult children showed appreciation for what the grandparents did for them, grandmother Song had this to say:

The child [the ten-year-old granddaughter] loves to eat fried chicken, so they sometimes take us along to eat at the school canteen. However, they do not make a deliberate effort to take us out for dinner.

Yet despite this intense sense of unhappiness, grandmother Song showed no signs of withdrawing her help. She told the researcher that she and her husband would help until her physical health no longer permitted it. Then, she would return to her hometown and spend her frail old age with her laoban (old companion, referring to her husband).

Conflict and tension

Grandmother Cheng – sense of bitterness in doing a thankless job. Despite not getting along well with her daughter, Grandmother Cheng endured for five years. Day-to-day interactions were tension-filled, a reflection of her relationship with her adult daughter. Grandmother Cheng expressed her puzzlement over her daughter's bad temper. The daughter, Madam Cheng, confessed that sometimes she would vent her frustration on her mother.

Not surprisingly, her mother felt rather bitter in doing this thankless job. It was not uncommon for her to weep while telling the researcher how she felt about her daughter. However, Grandmother Cheng seemed committed to helping because she could not see herself abandoning her daughter and granddaughter.

Positive regards

Grounded in the ethnographic data, the extent of voluntary acts of reciprocity in forms of taking over housework and childcare in the evenings, showing respect by avoiding conflict or giving of small gifts shown by adult children played a key role in countervailing the imbalanced relationship and facilitated grandparents' caregiving experience positively and sustained them in the caregiving roles.

Appreciation communicated by actions. During the six-month participant observation field work, the researcher noted that the middle generation of the Xie family exercised care in showing their appreciation to the two grandmothers. The paternal grandmother often called her son at his office to complain about her grandson. She would report in the child's little misbehaviours: how he pestered her to buy snacks and toys for him on the way home from school, how he refused to cooperate with his grandmother etc. Mr. Xie, the adult son, carefully handled these daily complaints from his mother. He admitted that she disturbed his work and often gave him headaches, but he would handle them as tactfully as he could. He would listen attentively, taking care to show his appreciation and validate his mother's effort in managing the child's misbehaviours. His wife, on the other hand, chose not to be involved, so as to avoid the complications of mother-in-law and daughter-in-law interactions.

The eighty-year-old grandmother who resided with the Xie family said she did not mind housework because she thought that cleaning, cooking and caring for her grandson kept her active and healthy. She reported that her daughter and son-in-law were, nevertheless, proactive in sharing the housework load. The middle generation would take over the chores when they returned from work in the evenings. For instance, Mr. Xie mopped the floor every evening and told his mother-in-law not to do the heavy housework. This grandmother claimed that she felt comfortable residing with her daughter and son-in-law. She complimented her son-in-law for being easy to get along with, and always helping around the house. The conscious effort in showing regard by Mr. and Mrs. Xie invariably caused grandmother to feel positively about the exchange relationships.

Having felt unfairly treated for a long time, Grandmother Kong eventually communicated her exhaustion and requested a redistribution of household chores. This brought about a gradual change in the dynamics between the generations. The adult son admitted:

To be honest, when my mother first came to help, we were busy and lao ren jia (old person ? grandmother) had to do most of the housework. Only when my mother expressed her unhappiness later on did I realise that it was not right of me to do that. She is here to help us and we pushed too many [house chores] to her. I reflected on this matter and did some redistribution of work.

Explicit verbal expression of gratitude. Mr. Guan was very grateful for the help his parents rendered him. In front of his older parents, Mr Guan expressed the following appreciation to the first author who conducted the interview in the small migrant quarters:

My parents lighten my load…both financial and practical burdens; they have helped me a lot. My parents are very understanding. My sisters also help me. Without all this support…the pressure will be too great for me to bear.

Grandfather Guan sometimes used rather harsh physical punishment with the boys when they misbehaved. The adult son showed his gratitude towards his older parents' help by deferring to grandfather's disciplinary style. The younger Mr. Guan said he did not mind the strict punishment.

No, I don't feel sorry for them. In fact I will affirm that grandpa did the right thing in front of the kids. Children need to be disciplined. Sometimes they need to be beaten or reprimanded. Other times we need to reward them [children].

Mr. Xie reported that he made known to his parents his appreciation of the help they rendered him:

I am usually respectful towards lao ren jia (old people). To me, having grandparents staying with me [or near me] is a great help to me. At least they relieve my worries, especially when I need to go travel for work. I know my child is in good hands.

Communication of regards through gifts Tokens of appreciations were also taken as a sign of reciprocity by the grandparents. The adult children took their older parents out for shopping and presented them with gifts. Grandmother Kong said,

Recently my daughter-in-law bought a new pair of shoes for me, she spent more than 100RMB on them because she knew I have a problem walking. I know this is her xin yi (token of appreciation). She also asked me about my impending surgery and talked about helping to pay for part of the medical bill. In recent years she seemed to realise how much I have helped her and now she is showing some signs of caring for me. As long as they show me some respect, I will be very happy.

Concluding discussion

By attending to the character of the symbolic value in family relationships[45] and the significance of regard in reciprocity[46] we explicate the mechanisms that underlie the positive or negative experience of caregiving by grandparents in Xiamen and what keeps the elder generation motivated to help their children. We will first describe the nature of grandparenting to set the context, then illuminate on the structural conditions that underlie the risk of non-reciprocity. Following that, we will utilise our ethnographic data, to provide an initial and tentative picture of the mechanisms that comprise the symbolic value of reciprocity (or lack of it). We will then describe and analyse the presence or absence of a particular symbolic value of reciprocity and its influence on grandparents' caregiving experiences, the motivation that keeps grandparents going, and how that in turn may impact intergenerational bonds between the older parents and their adult children.

Structural risk of non-reciprocity exists

Findings from the survey show that grandparents tend to provide childcare and other household help over a long period of time and at no cost, in Xiamen. A slightly more than majority of adult children (53.7 per cent) indicated that there is no need to reciprocate in any form since grandparents are part of the family. The risk of non-reciprocity is real for the reasons as borne out by the qualitative findings.

One, the grandparents' motives for providing services to their adult children include a desire to relieve them of their economic and social burden. In most cases, however, not only was there no conscious calculation of the cost involved, but the grandparents were ready to provide a unilateral contribution to their adult children on a long-term basis. Unlike in business transactions where an equal or unequal outcome for each exchange partner is obvious,[47] parent-child relationships are involuntary and life-long, and the equality or inequality of the relationship develops (and can be seen) and changes only over time. Hence, the long-term nature of reciprocal relationship tends to mask the costs suffered by the disadvantaged partner, in this case, the grandparents. Two, because the grandparents are joint caregivers with their adult children and the common goal is to provide the best care for the only child in the family, this collective goal veils and overshadows the fact that grandparents are giving far more than they receive in this reciprocal relationship. Grandparents consider that the welfare of the family should outweigh their personal loss.[48] Three, in intergenerational relationships, lack of reciprocity tends to be considered as an act of omission and not an act of commission. Since it is seen as an act of omission, the disadvantaged partner is less likely to attribute responsibility for the inequality to her partner as in the case of grandmother Cheng who attributed her daughter's outbursts to divorce. Omission is assumed to be unintentional and therefore, it should be pardoned as in the case of Mr. Kong who implied that the heavy workload imposed on the grandmother was an oversight and therefore the grandmother should not be upset. There may also be an issue of face here because adult children acting filial is a pride and desire of older parents and admitting that one's adult child is not filial is a dishonour. So, omission serves as an excuse for grandparents to explain away any lack of filial act from their adult children.

The symbolic value of voluntary acts of regard

The adult children demonstrated their appreciation and regard by allocating minimal chores to their older parents. The voluntary acts of reciprocity by adult children facilitate the older parents to frame their caregiving experiences positively. Another way of showing respect[49] has to do with managing potential conflicts with grandparents. Differences in childrearing attitudes and practices between grandparents and parents raising the grandchildren jointly are inevitable.[50] The adult children, through careful handling and according respect to their older parents, conveyed to them a sense of being valued. This might have offset, at least in part, the possible displeasure and resentment that could result from the stark imbalance of giving on the part of the grandparents.

From the data presented, it can be seen that even a very small gift from adult children would be magnified in meaning by the older parents. Most if not all gifts come with inherent instrumental usefulness.[51] However, when a gift is given voluntarily as an act of reciprocity in familial exchange (where risk of non-reciprocity is real), it has the potential of yielding values greater than its material or practical benefit. Under these conditions, reciprocity not only provides instrumental value, but symbolic value that communicates both the actor's regard for the exchange partner and the actor's willingness to invest in the continuation of the exchange relationship.[52] Both the functional and expressive values of the gifts serve to strengthen the guanxi between the two generations.

Salience of the conflict 'faces' of exchange

The nature of the help rendered by grandparents to their adult children's households is rather similar: mind the grandchildren, perform housework (cleaning, grocery shopping and laundry) and prepare meals—all of which are physically-taxing labour. The caregiving experience for grandparents nevertheless varied rather dramatically between grandparents Xie and Guan (pleasant and positive), and Kong, Song and Cheng (unpleasant and negative). A sense of being exploited and a feeling of bitterness were two prominent emotions expressed by grandparents Kong, Song and Cheng.

None of these grandparents attributed their negative experience to the lack of monetary or instrumental rewards. Rather, it was the lack of expression of regard and appreciation by the adult children in deeds, words or gestures that brought about a sense of being unfairly treated. One negative emotion expressed by the three sets of disgruntled grandparents was that they felt they were being treated worse than a domestic helper would have been. From the concept of guanxi, grandparents expect reciprocity as a basic form of renqing which is common even among non-family members. Lacking in acts of reciprocity signifies indifference[53] and heightens the severity of the felt injustices on the part of the giver of service. Moreover grandparents' perceptions that they were taken for granted due to children's indifference and disrespectful behaviours also seemed to tip the already lopsided relationship.

The role of pleasure and displeasure on intergenerational bonds

In an attempt to answer the second research questions we set out in the beginning of the paper, it seems a sense of appreciation, or regard, from adult children is what sustained grandparents in their long-term caregiving roles. Voluntary acts of reciprocity on the part of adult children may yield some material benefits for the grandparents. But more importantly, these acts communicate symbolic values of regard and acknowledgement of the grandparents' contribution made invariably lead to a sense of pleasure and satisfaction. These positive affects promoted the perception of fair dealing by the exchange partners and enhanced the intergenerational bonds. The voluntary acts of reciprocity could also be interpreted as acts of filial piety which bring pride and honour to the grandparents. On the other hand, inadequate or a complete lack of symbolic reciprocity would appear to spawn a sense of being exploited, anger and bitterness. That is, the more actors perceive their relation with exchange partners as conflicted, the more likely they are to hold the other party responsible for unsatisfactory outcomes and to perceive the other's exploitative behaviour as intentional (though it could be carelessness or neglect),[54] thus, in the cases here, contributing to the straining of intergenerational ties. As much as we believe the theoretical frame of symbolic value reciprocity is relevant and has good explanatory power in unpacking the mechanism of relational dynamics between grandparents as caregivers to their adult children's households, a caveat however, is needed. Molm's theory predicts that the severity of felt injustices increases the likelihood that disadvantaged actors will protest or take action to restore equilibrium.[55] In our sample however, it appears that most grandparents simply endure an imbalanced exchange relationship indefinitely and have no intention of restoring equilibrium. This is supported by survey responses that showed that approximately 40 per cent of adult children surveyed believed that their older parents would provide care and services indefinitely. From the ethnographic data, only grandmother Kong relinquished the role by using a culturally acceptable excuse of failing health. This tendency to persevere in caregiving warrants further research attention, in order to explore if some grandparents' psychological, social and physical well-being—especially those who experience anger and bitterness—are compromised as long-term caregivers. Often, the grandparents are reluctant to restore equilibrium in the imbalanced exchange relationship because it stirs negative emotions which disrupt the ganqing (feelings in the relationship), damaging parent-child guanxi.

The honour and burden of Chinese grandmothers

At this juncture some reflections on the nature of grandparenting in China are in order. Traditionally, due to the patriarchal ideals, women were relegated to a lower position than men in Chinese society.[56] Women were homemakers and men were breadwinners. Subsequent to the cultural revolution women's participation in economic activities increased. In China, therefore, today's grandmothers bring with them a blend of traditional as well as modern values.[57] Grandmothers are comfortable to stay with their spouses, visit their children in times of need and gain immense satisfaction in taking care of the grandchildren. Concern over their adult children's wellbeing and an unfaltering sense of familial obligation underlies grandparents', especially grandmothers' continuous help to their children. Despite the taxing nature of grandparenting and non-reciprocity from the middle generation, the grandmothers continued taking care of their grandchildren. Deborah Davis-Friedman suggests that in Chinese families, caring for grandchildren exemplifies the family's investment into the future.[58] As shown in our findings, grandmothers more than grandfathers are given the 'honour' and 'burden' of playing the venerable role of maintaining the bond that ties generations to ensure wellbeing and continuity of the family.

Concluding remarks

One limitation of this study deserves mention. The in-depth insights into the intergenerational dynamics between grandparents were based on data from observing five families (eight grandparents and eight adult children) over a six-month period. Despite the small sample, we feel that insights into such sensitive family issues could only be accessed through prolonged contacts and after building a trusting rapport between the researcher and the participants. The labour-intensive nature of the ethnographic method made it difficult to obtain a larger sample size. Hence, it is not our intention to generalise the findings. Instead, by combining the survey and ethnographic findings we provide a rough sketch of the mechanisms that contributed to either positive or negative caregiving experiences for grandparents. In addition, this paper reveals that the conflict and imbalance of exchange in these relationships were hidden by the conceptual and methodological limitations of past research efforts. This paper also underscores the significance of symbolic values of reciprocation through expressions of regard. These symbolic, reciprocal acts yield benefits far greater than their initial, instrumental gain. They make a vital difference to grandparents' experience of providing care in their adult children's households.

Appendix1

* f refers to the occurrence of the same code at the open code level

Appendix 1. Open, Axial and Selective Coding

Notes

[1] Jeo Leung, 'Family support for the elderly in China,' in Journal of Aging & Social Policy 9(3) (1997): 87–101; Heying Jenny Zhan, 'Chinese caregiving burden and the future burden of elder care in life-course perspective,' The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 54(4) (2002): 267–90; Heying Jenny Zhan, 'Joy and sorrow: explaining Chinese caregivers' reward and stress,' Journal of Aging Studies 20(1) (2006): 27–38; Heying Jenny Zhan and Rhonda Montgomery, 'Gender and elder care in China,' Gender & Society 17(2) (2003): 209–229; Heying Jenny Zhan, Zhanlian Feng, Zhiyu Chen and Xiaotian Feng, 'The role of the family in institutional long-term care: Cultural management of filial piety in China,' International Journal of Social Welfare 20(s1) (2011): s121–s134.

[2] Elisabeth, Schröder-Butterfill, 'Inter-generational family support provided by older people in Indonesia,' Ageing & Society 24(4) 2004): 497–530.

[3] Esther C.L. Goh, and Leon Kuczynski, '"Only children" and their coalition of parents: Considering grandparents and parents as joint caregivers in urban Xiamen, China,' Asian Journal of Social Psychology 3(4) (2010): 221–31; Merril Silverstein and Cong Zhen, 'Grandparenting in rural China,' Generations 1(7) (2013): 46–52.

[4] Esther C.L. Goh, 'Grandparents as childcare providers: An in-depth analysis of the case of Xiamen, China,' Journal of Aging Studies 23 (2009): 60–68.

[5] Chen Feinian, Guangya Liu and Christine A. Mair, 'Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China,' Social Forces 90(2) 2 (2011): 571–94; Chen, Xuan and Merril Silverstein, 'Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of oldr parents in China,' Research on Aging 22(1) (2000): 43–65; Schwarz, B. and Trommsdorff, G., 'Reciprocity in intergenerational support: A comparison of Chinese and German adult daughters,' Journal of Family Issues 31(2) 2 (2010): 234–56; Sheng Xuewen and Barbara H. Settles, 'Intergenerational relationships and elderly care in China: a global perspective,' Current Sociology 54(2) (2006): 293–313; Shi Leiyu, 'Family financial and household support exchange between generations: A survey of Chinese rural elderly,' The Gerontologist 33(4) (1993): 468–80; Yang Hongqiu, 'The distributive norm of monetary support to older parents: A look at a township in China,' Journal of Marriage and the Family 58 (May 1996): 404–415. This discussion excludes research on grandparents caring for 'left behind children' (liu shou ertong) in rural China where their adult children migrate to cities in search for jobs. Typically these studies are called skipped generation caregiving (ge dai fu yang) as the middle generation is absent. The current study is situated in Xiamen, a city at the South-eastern coast of China, hence, the skipped generation phenomenon is less relevant.

[6] Chen Feinian, Susan E. Short and Barbara Entwisle, 'The impact of grandparental proximity on maternal childcare in China,' Population Research and Policy Review 19(6) (2000): 571–90; Esther C.L. Goh, 'Grandparents as childcare providers'; Baorong Guo, Joseph Pickard and Jin Huang, 'A cultural perspective on health outcomes of caregiving grandparents: Evidence from China,' Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 5(4) (2007): 25–40; Susan Short, Fainian Chen, Barbara Entwisle, Fengying Zhai, 'Maternal work and child care in China: A multi-method analysis,' Population and Development Review 28(1) (2002): 31–57.

[7] Kwang-kuo Hwang, 'Filial piety and loyalty: Two types of social identification in Confucianism,' Asian Journal of Social Psychology 2(1) (1999): 163–83.

[8] Chen, Liu, and Mair, 'Intergenerational ties in context'; Sheng, 'Zhongguo Chengshi Laonianren De Jiating Shenghuo'; Sheng, and Settles, 'Intergenerational relationships and elderly care in China.'

[9] Baorong Guo, Joseph Pickard and Jin Huang, 'A cultural perspective on health outcomes of caregiving grandparents'; Feinian Chen and Guangya Liu, 'The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China,' Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Sciences Social Sciences 67B(1) (2012): 99–112.

[10] Ai-li S. Chin and Maurice Freedman, Family and Kinship in Chinese Society, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1970; William Parish and Martin Whyte, Village and Family in Contemporary China, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978.

[11] Linda Molm, 'Theoretical comparisons of forms of exchange,' Sociological Theory 21(1) (2003): 1–17.

[12] Marion Levy, The Family Revolution in Modern China, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1949.

[13] Maurice Freedman, Family and Kinship in Chinese Society.

[14] Yunxiang Yan, 'The triumph of conjugality: Structural transformation of family relations in a Chinese village,' Ethnology 36(3) (1997): 191–212.

[15] Sheng, and Settles, 'Intergenerational relationships and elderly care in China.'

[16] Chau-Kiu Cheng and Alex Kwan, 'The erosion of filial piety by modernisation in Chinese cities,' Ageing and Society 29(2) (2009): 179–98.

[17] Mette Halskov Hansen and Cuiming Pang, 'Idealizing individual choice: Work, love and family in the eyes of young, rural Chinese,' in China – The Rise of the Individual in Modern Chinese Society, ed. Halskov Hansen and Rune Svarverud, pp. 1–38, Singapore: NIAS Press, 2010; Yunxiang Yan, 'The Chinese path to individualization,' The British Journal of Sociology 61(3) (2010): 489–512.

[18] Charlotte Ikels,'The resolution of intergenerational conflict: perspectives of elders and their family members,' Modern China 16(4) (1990): 379–406; Ikels, C., 'Settling accounts: The intergenerational contract in an age of reform,' in Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era, ed. Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell, pp. 307–333, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

[19] Goh, 'Grandparents as childcare providers'; Ikels, 'The resolution of intergenerational conflict: perspectives of elders and their family members.'

[20] Giselle Trommsdorff, 'A social change and human development perspective on the value of children,' in Perspectives on Human Development, Family and Culture, ed. Sevda Bekamn and Ayhand Akus-Koc, pp. 86–107, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[21] Goh and Kuczynski, 'Only children.'

[22] Wenzhen Ye, Haizi Xu Qiu Lun- Zhong Guo Haizi De Cheng Ben He Xiao Yong (Theory of Children's Needs: The Cost and Profits of Raising Children in China-in Chinese), Shanghai: Fudan University Press, 1996.

[23] Le Lee, 'Day care in the People's Republic of China,' in Child Care in Context – Cross Cultural Perspectives, ed. Michael E. Lamb, Kathleen J. Sternberg, Carl-Philip Hwang, and Anders G. Broberg, pp. 355–92, Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1992.

[24] Goh, 'Raising the precious single child in urban China.'

[25] Goh, 'Grandparents as childcare providers.'

[26] Jieming Chen, 'When to give and why: Intergenerational transfer of resources in urban Chinese families,' in Social Change in Contemporary China, ed. Wengfang Tang and Burkart Holzner, pp. 233–60, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburg Press, 2006.

[27] Xiaotong Fei, 'Changes in Chinese family structure,' China Reconstruction, July (1982): 23–26; Xiatong Fei, From the Soil – the Foundation of Chinese Society, trans. Gary Hamilton and Weng Zheng, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

[28] Li Yinghe., 'Procreation and Chinese village culture,' Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1993.

[29] Hwang, 'Filial piety and loyalty.'

[30] Peng Du, 'Intergenerational solidarity and old-age support for the social inclusion of elders in Mainland China: The changing roles of family and government,' Ageing and Society 33(1) (2013): 44–63.

[31] Rita Chou, 'Filial piety by contract? The emergence, implementation, and implications of the "Family Support Agreement" in China,' in The Gerontologist 51(1) (2011): 3–16.

[32] Linda Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds: The role of emotions,' Social Structure and Emotion, ed. Jody Clay-Warner and Dawn Robinson, pp. 167–90, Boston: Elsevier, 2008; Linda Molm, David Schaefer and Jessica Collett, 'The value of reciprocity,' Social Psychology Quarterly 70(2) (2007): 199–217.

[33] Avner Offer, 'The economy of regard,' in The Challenge of Affluence: Self-Control and Well-Being in the United States and Britain since 1950, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 75–102.

[34] Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds'; Molm, Schaefer and Collett, 'The value of reciprocity.'

[35] Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds.'

[36] Offer, 'The economy of regard.'

[37] Andrew Kipnis, Producing Guanxi: Sentiment, Self, and Subculture in a North China Village, Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

[38] Andrew Kipnis,'"Face": An adaptable discourse of social surfaces,' Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 3(1) (1995): 119–48; Andrew Kipnas, 'The language of gift: Managing guanxi in a north China village,' Modern China 22(3) (1996): 285–314; Mayfair Yang, Gifts, Favors and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationship in China, New York: Cornell University Press, 1994.

[39] Mayfair Yang, 'The resilience of guanxi and its new deployments: A critique of some new guanxi scholarship,' The China Quarterly 170(June 2002): 459–76.

[40] Xiamen is made up of six zones namely Huli, Siming, Haicang, Xiang'an, Tong'an and Jimei.

[41] Martin Marshell, 'Sampling for qualitative research,' in Family Practice, vol. 13, no. 6, (2006): 522–26.

[42] Barney S. Glaser and Anselm L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968.

[43] Cheryl Peters, Karen Hooker and Anisa Zvonkovic, 'Older parents' perceptions of ambivalence in relationships with their children,' Family Relations 55 (December 2006): 539–51.

[44] The paternal grandmother walked her grandson to school in the morning, and made her way back. In the afternoon, she would go to pick the grandson up from school and take him home for lunch. After lunch she walked him back to school and at about 4 p.m., she would collect him from school. The school is about ten minutes from home.

[45] Molm, Schaefer and Collett, 'The value of reciprocity'; Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds.'

[46] Avner, Offer, 'Between the gift and the market: the economy of regard,' Economic History Review 50(3) (1997): 450–76.

[47] Molm, 'Theoretical comparisons of forms of exchange.'

[48] Goh, 'Grandparents as childcare providers.'

[49] Offer, 'The economy of regard.'

[50] Goh and Kuczynski, 'Only children.'

[51] There is a very long tradition in anthropology discussing the symbolic value of gifts with Marcel Mauss, (1967) as one of the key scholars. However, for the purposes of this paper we are drawing on the social psychological approach particularly the theory postulated by Molm and associates.

[52] Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds.'

[53] Offer, 'Between the gift and the market: the economy of regard.'

[54] Linda Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds: The role of emotions,' in Social Structure and Emotion, ed. Jody Clay-Warner and Dawn Robinson, pp. 167–90, Boston: Elsevier, 2008, p. 187.

[55] Molm, 'The structure of reciprocity and integrative bonds,' pp. 167–90.

[56] Lucy Fischer, 'Transition to grandmotherhood,' International Journal of Aging and Human Development 76 (1983): 67–78.

[57] Paula Bennett and William Meredith, 'The modern role of grandmother in China: A Departure from the Confucian ideal,' International Journal of Sociology of the Family 25 (1995): 1–12.

[58] Deborah Davis-Friedman, Long Lives: Chinese Elderly and the Communist Revolution, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

|