Fabric and the Fabrication of a Queer Narrative:

The Batik Paintings of Patrick Ng Kah Onn

Simon Soon

-

Just as Malaysia was hurtling into existence when the territories of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore willed its formation on 16 September 1963, Patrick Ng Kah Onn, a member of the Wednesday Art Group in Kuala Lumpur, began experimenting with a new series of batik paintings. Batik had just been declared a unique Malayan contribution to modern art in the previous decade.[1] The medium was seen as offering a technical innovation consonant with the initiation of a new national imaginary as Malaya achieved independence in 1957, one in which a traditional craft could be transformed into a modern form and channel new pictorial possibilities.[2] Art historian Zakaria Ali later wrote, 'We can argue that the identity of modern Malaysian art is in batik by proposing that we have used the sarung for hundreds of years, as noted in an early 15th century Chinese text.' He also wrote of the medium's affective potency, highlighting batik's sentimental trigger, 'Batik delivers something oils can never do: with batik we feel, smell, evoke, touch our homeland.'[3]

-

It is seldom acknowledged that the attempts to historicise batik as quintessentially Malayan and Malaysian, such as the claim above, are largely great works of fiction. Recent scholarship has begun to uncover the economies and discourses of the institutionally conceived modernity of Malaysia and the ways in which batik is imbricated within a nationalist art discourse.[4] In this context, batik has been metaphorically described as a sartorial skin that wraps and encircles the nation.[5] As an article of clothing it scripts the subject as cultural identity, connecting to the body politics of the nation. In the transformative use of batik from sartorial textile to painting support we see a deployment of form that brings to mind Charles Baudelaire's linking of modernity as 'the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent' to fashion.[6] This dimension suggests the fleeting characteristic of intimacy and is worth historicising, all the more so because batik painting continues to be discussed within the broader registers of cultural tradition and change.

-

Fabric can be understood as a second skin. It wraps, clothes, shields and embraces the body and in doing so, it not only scripts the body but its envelopment is a type of sensual configuration. The tactility of fabric is alluring and intimate. Writing about intimacy as a social matrix in which discourses of autonomy, social conformity and liberal values intersect, Elizabeth A. Povinelli's research brings to attention the central role intimacy can play in structuring social relations. She argues how this matrix is a space in which the social subjects acquire coherence and thereby become a legitimate object of inquiry for biopolitical discourses that vacillate between freedom and conformism as these discourses regulate bodily desires.[7] This, I contend, extends to the sartorial.

-

In batik paintings that emerged in Malaysia from 1955 onwards, we see intimacy and batik are transformed as tropes through pictorial fabrication. The registers of body and cloth become fluid categories through which to express desire. However, Patrick Ng's foray took it a step further. Here 'queering' was centred on a discourse of plasticity that brought into discussion questions of what types of bodies can make claims on sensuality via figurative representation.

-

The framework of queering conspires towards the possibility of a narrative outside the cultural expressions that accompanied struggles for politicisation of sexuality in parts of Europe and North America from 1970s onwards.[8] This possibility allows us to explore an alternative history of modern art, outside European and American contexts.[9] The desire for such narrative is beguiling. It signals the possibility of rethinking the location of desire within the story of modern art in Asia—a questioning of the commonplace trope of the body and its figuring of nationhood within hetero-normative discourse. This trope has been so central to many post-colonial readings,[10] in which the allegorical female body stood for the nation in artworks by male artists and signified what Geeta Kapur described as, 'a relay of male desire, female vocation, and national culture, posed for unabashed viewing outside the margins of history but potentially inside a national pictorial scheme'.[11]

-

Thus when we encounter what appears to be a different pictorial reservoir, we are invited to think of a 'queer before gay' moment in Southeast Asia, to borrow Douglas Crimp's phrase.[12] By this I understand Crimp to suggest that over and beyond the cultural production that attended to and followed from the gay and lesbian liberation movement, one could perhaps think of other ways of articulating and negotiating with desire that operated outside of and very often before this 1970s political trajectory. Instead Povinelli's concept of intimacy as a social matrix creates room for speculative inquiry in which the anecdotal and tentative map out possible sentiment rather than certainty. Often enough, the anecdotal forms a significant corpus of material and a methodological tradition for the study of art history.[13]

-

A queer narrative in Southeast Asian modern art can examine how discourses of batik painting that had once been pressed into service as a unique Malayan and later Malaysian contribution to modern art were frayed on the edges by other codes and models of affectation and staging. Here fabric as medium can suggest a processual register: to fabricate as verb. Can the batik as painted form envelop anything other than a culturally national body? What role does speculation play in art history as it fabricates possibilities and uncovers potentialities in histories that might otherwise remain tentative and hidden?

Brown bodies

-

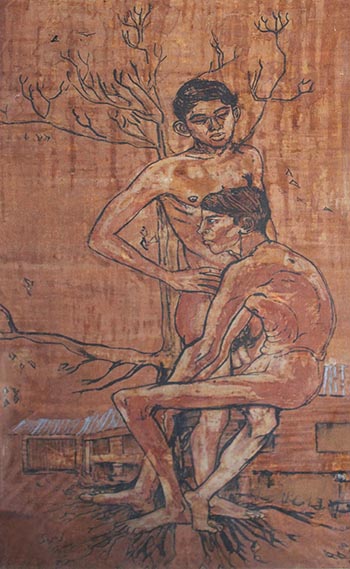

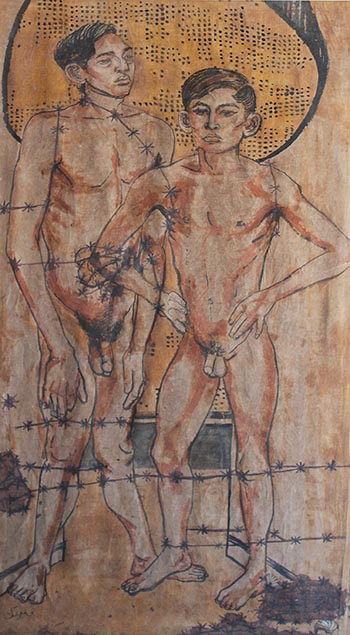

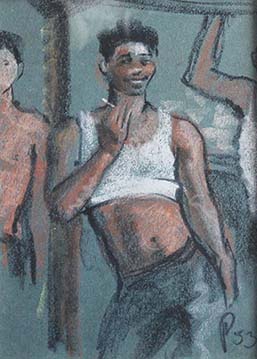

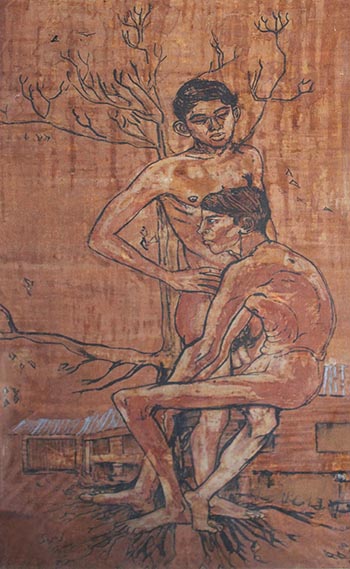

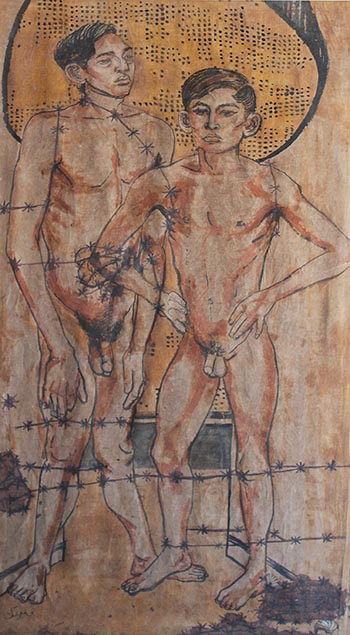

Patrick Ng's batik paintings were first exhibited in 1962 at the Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Wednesday Art Group, held at the British Council Hall in Kuala Lumpur.[14] Reviewing the exhibition, Frank Sullivan—writing under the pen-name Chermin (Mirror)—noted, '[He] shows for the first time his brand-new pre-occupation with batik painting, exhibiting seven nude figure compositions in brown and white, so reflective that the artist himself could be described as being in a "brown study"' (Figures 1, 2 and 3).[15]

Figure 1. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Pohon (A Tree), 1962, batik, 86 x 40 cm. Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang |

|

Figure 2. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Perpisahan (A Separation), 1962, batik, 86 x 40 cm. Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

|

Figure 3. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Youth Embarbed, 1962, batik, 86 x 40 cm. Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

|

-

It was obvious why Chermin,[16] in a stroke of art historical conceit, would label these batik paintings as Patrick Ng's 'brown study.' The palette is limited to ochre and the overall tone of the paintings is earthy. Yet in the three examples illustrated each painting shows two full body male nude figures in various poses, compositionally central within the vertical frame. They take up most of the space and perform narratives hinted in the title of the paintings. But it is unclear if the narratives and the protagonists are comparable in each painting or whether or not the seven works were intended to be read sequentially.

-

The titles of the first two works, Youth Embarbed and Separation, conjure an image of desolation. The first intimates restriction and constraint, the latter suggests severance, finality and a movement apart. In the former the figures are enmeshed by barbwire, which coils from their knees up to their arms and the latter shows one of the young men's backs turned towards the viewer, as if he is walking away from the scene. In the third painting Pohon-which translates to 'tree' in Malay—the bare branches of a dying tree could yield to the suggestion that such bleak iconography was drawn from Samuel Beckett's existential play, Waiting for Godot, here recast as the melancholia of a tropical gothic. We see a wooden house in the background; a domestic symbol of either rural or working class. The somber tenor in all three works evokes ennui as it casts the vigour and health of the respective two young male bodies, seen in their prime, against the undercurrent of apprehension, clouding these figures. They are posed yet seemingly unaware of the gaze of the viewer.

-

These 'brown' bodies are also significant because of a slippage at play; they are nudes depicted with the batik medium, a method of painting that has sartorial origins. Here the signifier of batik as cloth, as covering, is subverted by bringing the nude body and the batik cloth together, and in exposing the tension between the nude and the clothed, Patrick Ng had also collapsed these two registers of the body. Such a collapse suggests an expression of anxiety. The intimation of emotional tension between the two figures, whether platonic or sexual, underlines a fraught expression of desire within homosociality.[17] For the academic Michael Hatt, this sense of the indeterminate can be understood as the very definition of homoerotic, in which the ambiguous tension 'situated on the boundary between the homosocial and the homosexual, [relies] upon normative male-male relations but simultaneously and necessarily [invokes] what lies beyond that norm: the Utopian space of male homosexuality.'[18]

-

In effect, the paintings responded divergently to a discourse of modernism that characterised batik painting as a fine art medium, intersecting a moment when a distinctly modern Malayan (and later Malaysian) art was being summoned into being. The credited innovator of batik as fine art—circa 1955—is Penang-based artist Chuah Thean Teng and his works exemplified what academics E.J. Hobsbawm and T.O. Ranger characterised as 'invented tradition.'[19] Though Hobsbawm and Ranger would distinguish 'invention' from 'starting' or 'initiating' a tradition, which does not then claim to be old, here batik painting articulated both innovation and tradition yet was often exclusively spoken about in terms of its stability as a marker of Malayan/Malaysian culture.[20]

-

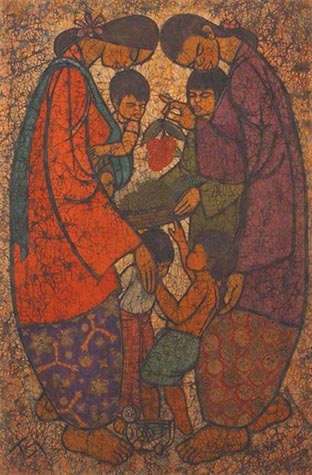

Frank Sullivan ()as Chermin) was also able to highlight the merit of batik painting as having both avant-gardist aspiration yet marked as cultural patrimony for the region. He notes, 'It is astonishing to think that although making batik has been common for hundreds of years, no one before Teng [Chuah] ever thought of adapting this age-old craft as a medium for fine art. Teng, and Teng alone, is responsible for this most original contribution to the whole world of art.'[21] This claim stakes out Malaysia's contribution to a universal modernism by innovating batik as a new type of painting support and thereby sanctifying tradition as a wellspring of innovation (Figures 4 and 5).

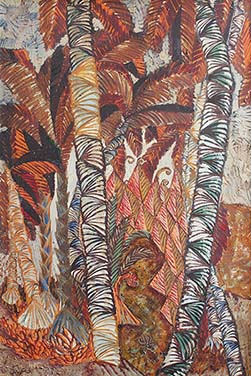

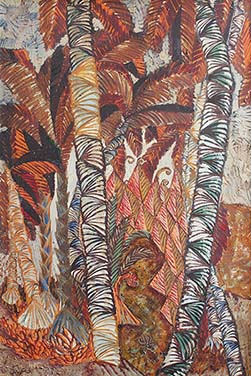

Figure 4. Chuah Thean Teng, Di Bawah Pohon Palma (Beneath the Palm Tree), 1965, batik, 90 x 66cm. National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia |

|

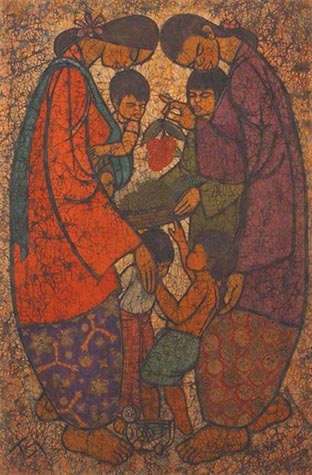

Figure 5. Chuah Thean Teng, Musim Buah (Fruit Season), 1968, batik, 87.7 x 57cm. National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia

|

-

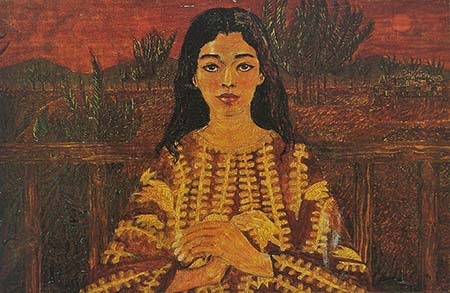

As Di Bawah Pohon Palma and Musim Buah demonstrate, Chuah's iconographic repertoires were primarily village scenes and representations of busty women-folk.[22] Intersecting this Malayan imaginary was the concept of the nanyang,[23] which sprang from an immigrant community's appeal for homeland through nativist tropes and iconography.[24] Chuah's compositions are schematic—focused primarily on a graphic linearity of form—and in comparison, Patrick Ng's paintings appear muddy.

-

The nude bodies in Patrick Ng's paintings are shaded to suggest volumetric space, perhaps drawing on the conventions of European figuration. This lends psychological gravitas to the principal figures while Chuah applied clean blocks of colour delineated by very precise outlines, with no shading, and consequently created a cartoon-like quality in his approach to batik. Patrick Ng seems to have sought an alternative to this graphic outline, so that he could arrive at a form suitable for the pictorialisation of a mood and atmosphere that is altogether different than Chuah creates.

-

Yet even as Chermin's assessment of Chuah was written in 1963 when Chuah's meteoric rise to fame had earned him both commercial success and broad acceptance, the unsettling of batik as a register of a Malaysian modernism was being challenged by Patrick Ng's exploration of the medium. My contention is that when placed in context and connection with Patrick Ng's fascination with the sartorial tradition of the region as captured in his earlier works in oil, his batik paintings demonstrated queering as an operative gesture and model within the story of modern Asian art.[25]

-

To entertain such possibility is to suggest that the practice of queering could unsettle the claims of batik painting's myth of origin in the figure of Chuah and therefore complicate the discursive models that have narrowly located batik's modern discourse solely within a Malaysian art historical trajectory or its pre-modern history as a broadly Southeast Asian customary heritage. This mainstream narrative was perhaps the central argument proposed by the newly established Batik Paining Museum in Penang in 2013.[26] Queering is therefore an attempt at fabricating an explanatory grid that is analogous to how Judith Butler notes that homosexuality exposes heterosexuality as 'an imitation of an imitation, a copy of a copy for which there is no original … an incessant and panicked imitation of its own naturalized idealisation.'[27]

-

In this regard it is very significant that the bodies are brown. The convention of the nude undresses the body and reveals the tone of skin. These are racialised bodies, bodies that intimate locale or turn to geography in the use of tone to collapse the relationship between figure and ground.

-

To further explore how locale is understood, two unstable registers need to be deconstructed: the national and the regional (which have continuously shaped readings of Patrick Ng's artworks). I want to visit these significant nodes in order to unpack their agencies and underline their limits. This is with the view that a strategic perturbation could open a way to examine undercurrents of desire and the bonds of friendship that structured Kuala Lumpur's art world in the 1950s and 1960s as a 'queer before gay' moment in art history.

Queering the national and regional

-

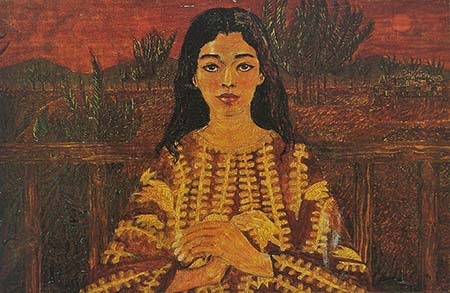

Two paintings serve as significant precursors to Patrick Ng's subsequent engagement with batik as a medium. These are Semangat Tanah, Ayer, dan Udara (1958) and Batek Malaya (1957). The works signal specific tendencies and impulses that destabilise registers of national and regional that were so closely entwined in subsequent readings of these two pictures (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Batek Malaya 1957. Private Collection, the Philippines |

|

Figure 7. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Semangat Tanah, Ayer dan Udara (Spirit of Earth, Water and Air), 1958, oil on canvas, 137 x 122cm. National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia

|

-

Batek Malaya can be seen to be prospecting a shared heritage; the painting depicts a group of womenfolk hanging sheets of batik cloth out to dry. There is a an attempt to overwhelm the pictorial surface with the exuberance of the fabric pattern and collapse the figure/ground relationship as the naïve rendering of form flattens the very clothes worn by the women against the compact backdrop which features batik cloths. Batek Malaya won Patrick Ng critical acclaim at the young age of twenty-four. The work was awarded first prize at the First Southeast Asian Art Conference and Competition 1957 in Manila during 1957.

-

The academic Farish Noor has made a case for batik as the lingua franca of Southeast Asia.[28] However, this romantic reading tends to overstretch the historical accuracy of batik's transnational currency for a polemic that addresses contemporary politics, without attending to the specificities of cultural and political contexts that allowed the instrumentalising of batik. But Farish's proposition resonates in many ways with the goals and purpose of the 1957 competition.[29] This landmark event, organised by the Art Association of the Philippines (AAP) in cooperation with the Asia Foundation, would go down in history as the first exhibition that attempted to frame culture through some kind of regional framework.[30] One can speculate if this was the reason that Patrick Ng's painting was chosen as the winning entry.

-

On the other hand, in Semangat Tanah, Ayer, dan Udara a cosmology of the Southeast Asian life-world is represented with a symmetrical composition which suggests dynamism and order.[31] In a later assessment, artist turned curator Redza Piyadasa notes, 'Patrick Ng's eclecticism is clearly discernible in his ambitious borrowings from Malay, Balinese, Thai and Bornean sources. The complexity on the artist's part to re-construct a symbolic universe that had its roots within the larger cultural contexts of the Southeast Asian region makes this work one of the visionary paintings in the story of modern Malaysian art.'[32] Under the National Heritage Act enacted in 2005,[33] Semangat Tanah, Ayer, dan Udara, was included in the heritage registry Dafter Warisan in 2009.[34] The painting can therefore be counted as Patrick Ng's best known artwork in Malaysia.[35]

-

In these two examples of Patrick Ng's paintings from the late 1950s, I have highlighted how their circulation within national and regional registers matched specific political urgencies, shaped by a post-colonial eagerness to will aesthetics in the service of nation while also prospecting a larger unit of cohesiveness. As founder of the AAP, Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, reminiscing on the First Southeast Asian Art Conference and Competition, wrote, 'Two important ideas emerged.… The first was that all men are brothers [sic] and art transcends all barriers because it is universal. The second—and this may not be as diametrically opposite as it may seem—was a belief in national identity.'[36]

-

Given that Batek Malaya went into a Philippine collection after the competition, it is unsurprising that Patrick Ng seemed to create a similar painting in light of the win.

-

The forms of Menyidai Kain (Hanging Cloth), which is currently part of the National Art Gallery of Malaysia's collection, were described as 'white mask-like faces of the women … very much like a rich Persian miniature.'[37] In this work, a linearity of form is further augmented and favoured over the expressive brushwork of the original painting, as if taking cue from the batik method of wax resistant dyeing that contributed to the sharp outlining of forms such as in Chuah Thean Teng's entry to the same competition Small Boats (1957); also featured in the pages of the catalogue (Figures 8 and 9).[38]

Figure 8. The First Southeast Asian Art Conference and Competition exhibition catalogue. Source: Vargas Museum, Manila

|

|

Figure 9. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Menyidai Kain (Hanging Cloth), undated, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 60.9cm. National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia

|

-

The move to manifest what was deemed to be quintessentially batik could be seen in the oil painting Kejadian Batik (Genesis of Batik) (1960) (Figure 10) in which the accentuation of outlines and patterns have now superseded subject matter altogether, as they are mapped onto the tropical plant image and highlight the design's decorative origins and inspiration.

Figure 10. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Kejadian Batik (Genesis of Batik), 1960, oil on canvas, 90.1 x 61cm, Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery. Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang |

|

Figure 11. Hand carved wood printing block. Block is carved from a single piece of wood with raised handle on top, early 20th century, 13.3 x 11.4 x 6.3 cm. Michigan State University, Museum Cultural Collection Where in the text shall I mention this one

|

-

If we were to take Menyidai Kain as a move by Patrick Ng to think through another medium, a search for a batik technique in order to depict a 'batik subject' in oil, then by the time he decided to work with the batik medium in 1962, he was demonstrating a reversal of priority. Or, he was to push the batik medium towards more painterly expression. Here, in order to represent the psychological tumult experienced by the figures in his batik paintings, Patrick Ng would reject the schematic lines that defined the graphic image as batik's formal property—hitherto developed by Chuah Thean Teng—as if to expose the conceit of the painterly support through which a craft tradition was to be transformed into a fine art medium. And by opting for a more painterly style, Patrick Ng was at the same time seeking to capture the interiority of male bodies as vehicles for emotions.

-

What is the quality of this interiority? I suggest that Semangat Tanah, Air dan Udara might hold some answers. In Piyadasa's reckoning, the success of the painting lies in its broad encapsulation of the region as a matrix of visual languages and sources.[39] Here I will connect the painting to two Balinese artworks in order to arrive at a constellation of how the social intersected with the personal in the pictorialisation of desire.

-

One striking reference that has often been considered in Semangat is that the grouping of figures is reminiscent of the Balinese Kecak/monkey dance.[40] Kecak as an innovative and modern dance performance is familiar to many dance and music ethnographers, yet it has acquired the patina of age through the branding of tourism and is often billed as traditional Balinese dance.

-

The role that Walter Spies played in either introducing or facilitating its modern form has been discussed and contended elsewhere,[41] but it is undeniable that Spies played a central role in promotion and dissemination of the dance performance.[42] A number of queer readings of Kecak have recently been advanced. One central claim had been the exploitative relationship between the white man and the native as constitutive of the colonial experience.[43] However, this type of reading falls into the trap of caricaturising colonial tropes, discounting the agential narrative that could exist outside the trope of exploitation and beyond the binary of the subjugated native and oppressing white man. Perhaps a more sensitive reading can be found in Gary Atkin's book Imagining Gay Paradise where the author considers the Kecak in relation to Spies's search for a homosocial and sensual compact that he found in Bali.[44] Bodies huddled in close proximity as men entered into a trance-like formation spoke of a kind of body politics resulting from the ritualising of male bonds.

-

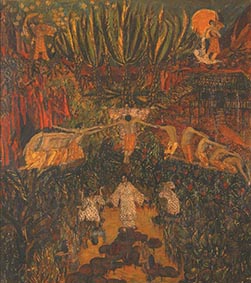

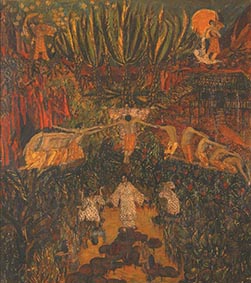

The spectacle of the Kecak as an all-male participatory performance can be seen in the film Island of Demons (1933). Though billed as a dramatic thriller, the director, Baron Viktor von Plessen, came to Bali without a script and only a list of what to shoot including scenes of agriculture, harvest, religion, cock fighting and dances such as the Barong. Enlisting the help of Walter Spies as art director, Spies made the Kecak a significant feature in the film (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Film still of Baron Viktor von Plessen, Island of the Demons, 1933, choreography and casting by Walter Spies. Image from public domain |

|

Figure 13. Ida Bagus Madé Tibah, Ritual: Mantenin padi for storing new rice, 1937, previously in the Bateson-Mead Collection, currently in Private Collection, Los Angeles. Image taken from Virtual Museum of Balinese

|

-

In spite of the movie's plot being typecast as a thriller, Island of Demons was really a compositional litany of Bali. It tells a love story between two villagers and the disruption to their bucolic life by Rangda, the demon queen. The story was interspersed and framed by scenic landscapes as well as dances and rituals (Figure 13). Shot in black and white, the cinematic tone and composition of Island of Demons has yet to be compared to the paintings of Batuan artists. This comparison requires creative interpretation and license but is a productive one.

-

The Batuan are a group of artists from an eponymous lowland village who were urged to develop their own style of painting by Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet.[45] Nevertheless, the subsequent popularity of Batuan paintings largely resulted from one of its artists, I Ketut Ngéndon, who demonstrated business acumen and ingenuity by encouraging his fellow villagers to paint and then promoting these artists to foreigners.[46] In many ways these black and white tonal paintings—compositionally baroque in a meticulous attempt to fill every available surface with detail—resonated with the qualities that are spectacularly cinematic in Island of Demons. This is especially so if we consider these paintings in relation to the frenetic dance sequence of the Kecak in the latter. In the film there is also an attempt to achieve an all-over effect, conveyed not only through montage but also in the multiplication of tightly knitted bodies that take up most of the frame such, as Figure 12 demonstrates. A sense of the cosmological rhythm of Balinese life that constituted the visual spectacle we see in the Batuan paintings is conveyed.

-

Moreover, the schematic layering of planes in a vertical arabesque such as in Ritual: Mantenin Padi for Storing New Rice bears striking resemblance to Patrick Ng's Semangat. There is no direct connection that could link Patrick Ng's painting to Batuan imagery, nor any evidence of Batuan paintings exhibited in either Kuala Lumpur or Singapore. However, we know the fascination that Bali held for the Chinese immigrant community in Malaya.[47] In the absence of evidence, one could furthermore speculate whether a 1959 exhibition of Indonesian art at the National Art Gallery of Kuala Lumpur, showcasing ninety artists and 169 works of art under the sponsorship of the Indonesian government, included any Balinese artworks. The exhibition was recorded as very well attended and Patrick Ng being an active member of the Wednesday Art Group would have very likely counted amongst the audience.[48]

-

A comparative triangulation can be achieved if we place the Kecak, the Batuan paintings and Patrick Ng's paintings together. These are all modern expressions that turned to tradition as a resource to pictorialise social bonds. As such one could think of Patrick Ng's recourse to the store of tradition as a means of locating an imaginative vector. Could the region then become a space to imagine bonds of affection against the restrictions on non-normative intimacy?

Bonds of friendship and affection

-

When Redza Piyadasa wrote on Patrick Ng, he noted,

the search was for stylization and a decorativeness that evoked essences of the region and its sensibilities. That he displayed deep feelings for indigenous traditional Malay culture was reflected in his having joined a Malay dance group during that period. Again, he always signed his paintings in Jawi. Delving into the traditional forms, myths and world-views of the pre-colonial past, he attempted to infuse his works with characteristics and meanings that allowed for artistic complexity.[49]

-

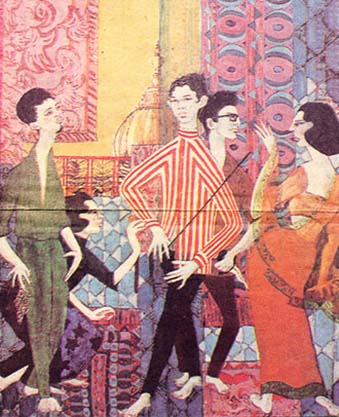

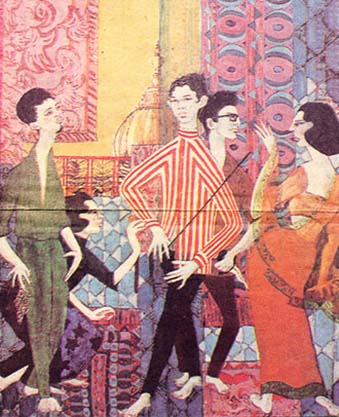

But there was another side to Patrick Ng that is seldom addressed in the haste of art historians to frame his work as an engagement with tradition and region. Part of this has to do with the cosmopolitan affectation that is so central to the projection of worldliness in a young artist emerging in the mid-1950s at the cusp of Malaya's independence in 1957. A work executed a decade later titled Self Portrait with Friends (1962) brings the atmosphere of then contemporary Kuala Lumpur alive. An opening amidst the drapery of textiles allows us to identify in the distance a Kuala Lumpur landmark, the copula of the Neo-Mughal Jamek Mosque, constructed in 1910 at the confluence between the Klang and Gombak rivers and which gave Kuala Lumpur her name—literally meaning 'Muddy Confluence.'

-

No longer positioned as a backwater town in relation to Singapore, independence refashioned the artistic milieu of Kuala Lumpur as urbane and chic. This is also not the nanyang, the Chinese-dominant cultural milieu of Penang and Singapore. Here Patrick Ng is seen with friends who are most likely artists from the Wednesday Art Group (WAG), including a young Syed Ahmad Jamal in a green overall on the left. Artists from different ethnic backgrounds gathered under the British colonial expatriate Peter Harris, an art superintendent of the Federation of Malaya from 1951–1960. They met every Wednesday under Harris's tutelage to paint.[50]

-

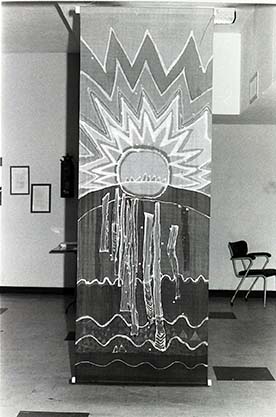

In Self-Portrait with Friends, Patrick and his friends are surrounded by a lush display of patterned textiles in bold colours and large inventive designs (Figure 14). This suggests that the textile works of Grace Selvayanagam could have inspired Patrick Ng's fascination with fabric design, even if Grace was not a member of the Wednesday Art Group (Figure 15). One suggestion that points to Grace as a source of inspiration was that she favoured large designs over small ones. This can be seen in the fabric design in Self Portrait with Friends.[51]

Figure 14. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Self Portrait with friends, 1962, oil on board, 27.5 x 23.5cm, National Gallery Singapore. Image taken from public domain |

|

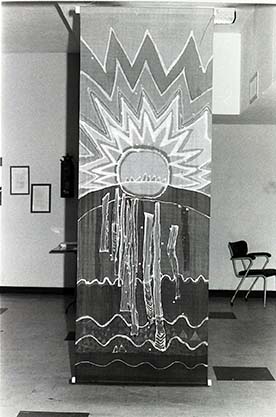

Figure 15. Photograph of Grace Selvanagam's textile piece for Manifestasi Dua Seni (Manifestation of Two Arts) exhibition 1970 at Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Based on Kassim Ahmad's poem 'Dailog (Dialogue).' Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.[52]

|

-

Patrick Ng had fostered a generation of protégés, amongst them Hajeedar Majid, Ismail Mustam and Dzulkifli Buyong, from his influence and contribution to art pedagogy extended to two high schools, the Methodist Girls' School and his alma mater Victoria Institution, a high school located in the city centre, where he taught art from 1956 to 1963.[53] All of them went on to join the Wednesday Art Group and would also later achieve national recognition in their own right.

-

By signing his name in Jawi, wearing Malay dresses, capturing the electric pulse of the city as it would assume increased importance as the new capital of Malaya by 1957, Patrick Ng's affectation of urbanity cast a sartorial fascination with what is sometimes deemed to be 'local' (Figure 16). What can we make of this milieu? A 1964 pastel drawing by Dzulkifli Buyong provides an interesting clue. Curator J. Anurendra would describe the scene as, 'Floating above a row of lilies, against a pastel blue sky are four young men, arms interlocked and sarongs filled with the rush of buoyant air' (Figure 17).[54]

Figure 16. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, second from right, in the Victorian Institute art room. Image from public domain |

|

Figure 17. Dzulkifli Buyong, Four Friends, 1964, pastel on paper, 110 x 75cm, Private collection, Kuala Lumpur

|

-

In his interview with Redza Piyadasa and Ismail Zain, they have argued that the figures represent different personalities. Anurendra notes, 'One version is that they are [Redza] Piya[dasa], [Syed Ahmad] Jamal, Latiff [Mohidin] and [Cheong] Laitong. Another version has Patrick instead of Laitong and Ib [Ibrahim Hussein] instead of Jamal … needless to say it almost becomes a moot point since their identities are interchangeable. Together, these are the artistic parents of our modern movement.'[55]

-

It is a strange metaphor to connect a representation of four men in indeterminate customary Malay attire that could either pass as a male Baju Melayu without the samping or the female Baju Kurung to the concept of parenthood. Yet I want to take this metaphor as an opportunity to consider how we could imagine a cultural space in 1950s Kuala Lumpur.

-

The painting above could be understood in relation to Patrick Ng's Self-Portrait (1958) (Figure 18) where he is represented with long hair and dressed in a batik outfit with a motif not unlike those we see in his experimentation with pattern in Kejadian Batik. Writing on the dressing of the body in Malaysian art, art historian Izmer Ahmed has gendered this modality of cultural production. He notes, 'the "textile" body is a body composed of marks. When coupled with the maternal metaphor, this inscriptive power of cloth to provide intelligibility and meanings to the body is radicalized.'[56]

Figure 18. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Self Portrait, 1958,

oil on paper, 50 x 75cm. Ismail Mustam collection

-

In this sense, this mark is not the kind of Islamic identitarian mark that became prevalent in the post-1970s competing vision of Islamism.[57] As argued by Izmer, instead, reference to the batik tradition,

subdues the Islamicist discourse and is closer to the state's position and its cultural mission to inscribe and legitimize the bodies and identity of its citizens … the result of this is the community and the nation that is held together by symbols, summarized in modern Malay/sian art through the figure of the mother as the symbol and body of the nation.'[58]

-

But Patrick Ng's self-portrait takes this further. It queers this Malay/sian ontology on two registers. The first is through a gender shift from male to female by cross-dressing himself as a woman in the self-portrait. The second, a shift from Chinese to Malay. Here he makes visible an anxiety of cultural politics that have constitutionally defined Malay cultural markers. After all, as defined by the Malaysian Constitution; anyone can become Malay (masuk Melayu) by adopting Islam and practising Malay customs. But, in doing so, Patrick Ng's performance of cultural competence and mimicry is a challenge to the cultural codification of the period in terms of gender and the racialised body.

-

It could very well be that these four figures also represent the four artists that were examined in Patrick Ng's own graduation thesis: Chuah Thean Teng, the late Syed Ahmad Jamal, Long Thien Shih and the late Nik Zainal Abidin. According to his brother-in-law (who inherited the unpublished thesis), it was 'painstakingly written on large sheets of art paper in Patrick's elegant copper-plate handwriting.' Included in the thesis were reproductions of important works by these artists, painted by Patrick Ng himself.[59] In replicating works by his peers and colleagues, an attempt is made to bring to this period an historical purchase as well as an index for the milieu that were formative to his social and cultural life in Malaya. If the painting by Dzulkifli Buyong, one of Patrick's most promising protégés, is anything to go by this world also afforded the possibility of friendships that were permissive, open and accepting enough to include all the queer personalities in search of a space to make meaning out of their artistic desire.

-

These works also illustrate a very different picture from the batik artworks that Patrick Ng would come to paint by 1962. The tone of the batik paintings intimated inner turmoil. Patrick Ng would leave Malaysia in 1964 under the Sino-British fellow trust to study art at the Hammersmith College of Art and Building and he continued to major in fine art and textiles at the Southlands Teacher Training College, both in London. Save for sporadic visits back to Malaysia Patrick Ng made London his home. Though he complained about the conservatism and dogmatism of the British art school he was sent to, hinting at the discrimination he faced, he spoke longingly for 'a gulp of fresh Malaysian air.'[60]

-

It was therefore ironic that he decided to stay on in London. The reason given was that he preferred the stimulation afforded, 'by the lively scene in London—opera, theatre and art galleries.'[61] Here we can ask: did Patrick Ng's batik paintings hint at dark clouds ahead were he to stay on in Malaysia? Was this prescient that social mores would take a very different turn? Or did the paintings register something more personal? A heartbreak? Anguish over a separation?

-

As the 1960s marched on, Peter Harris left for Sabah and later returned to England. Frank Sullivan, the Australian press secretary of the Prime Minister of Malaya who took up Malaysian citizenship and invested much of his time setting up and running the National Art Gallery was ultimately pushed aside for the directorship of the institution following the National Cultural Policy of 1971 in favour of an ethnic Malay candidate.[62] In the end, he was compelled by economic and social circumstances to request the return of his Australian citizenship and he spent his last years in Melbourne.[63] Sullivan's life story therefore indicated the narrowing opportunities for those who seemed foreign or did not fit into the specific cultural discourse that defined the Malaysian national imaginary, which was soon to be framed by Islam as the official religion of the country as the 1970s marched on into the 1980s, precluding most cultural expressions that were contrary to the values of a Malaysian discourse on culture.

-

In this respect one can argue that Patrick Ng's batik paintings captured a fleeting moment in Malaysian art and cultural history. While he indicated a time and space in which the cosmopolitan affectation drew worlds inward into Kuala Lumpur, he also ultimately signalled how this Malayan world and hope came to a close as Malaysia came into being.

The strange fabric of art history

-

I have sketched the kind of permissive space afforded to artists in Kuala Lumpur in the late 1950s following Malaya's independence in 1957 and the eventual demise of this space as Malaysia came into being in 1963. The recognition of such a space has been hitherto elided by the kinds of political urgencies that resulted in a postwar narrative of national and regional art histories—narratives we are very familiar with now.

-

I have prioritised speculation as a methodology of 'queering,' as a means to locate possibilities in a narrative of queer art history in Southeast Asia. This animates the artworks and allows us to think through geography as a postcolonial index. Thus we can recover resonances that might otherwise be sidelined by the narrow purview of nationalism as a politically dominant discourse.[64]

-

Such resonances are not altogether unfamiliar to art historical enterprises. We can locate it in the classical ideals advanced by the eighteenth-century pioneer of the field, Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Winckelmann argued for a classical paradigm of aesthetic perfection patterned along ideals of male beauty found in Greek sculptures.[65] For him, this perfection of masculine form corresponds to core humanist values and morality, centred on the notion of personal and political freedom.[66] As such, Winckelmann would argue that any society possessing such political, social and intellectual conditions could foster these values. In doing so, his art historical thesis also doubly served as a manifesto. It summoned for and anticipated a neo-classical revival to come.[67] Such a revival would be incarnated in the ideal moral man as represented by the perfection of the male figure.

-

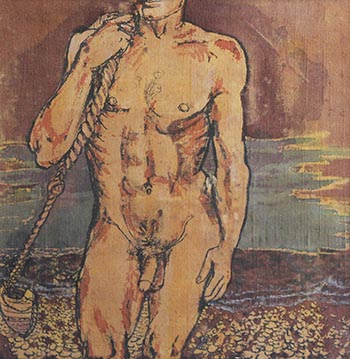

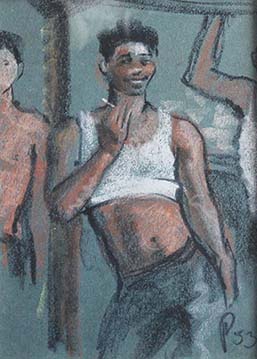

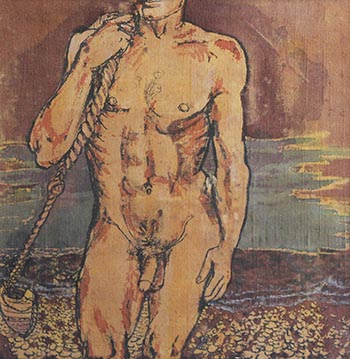

Was there an afterlife to the aspiration of Winckelmann as it was refracted through political and aesthetic ambitions in late 1950s Malaysia within an artistic milieu buoyed by the democratic spirit of the time, the moment where Malaya achieved independence?[68] We may, in this instance bring, two works into comparison: Peter Harris's Having a Smoke (1950) (Figure 19) and Patrick Ng's Bogel (Nude) (1962) (Figure 20). Both works evinced the sculpted form of the male body, staged in the familiar classical pose of contrapposto. With a sleight of hand, the conspiring smile of a working class male figure as he holds a cigarette in hand, leaning nonchalantly against the pillar with his white singlet rolled half way up and his midriff exposed, can be seen to possess a new erotic charge when seen side-by-side with Patrick Ng's nude torso. In Patrick Ng's painting, the body of the labouring man is brought into relief; perhaps he is a fisher as the background of the painting shows a shoreline. The representations here take on a class dimension, a bourgeois desire framing the working man's body that toils in the process of nation-building. They are fantastical but tender all the same.

Figure 19. Peter Harris, Having a Smoke, 1950s, pastel on paper, 35 x 22 cm. Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang |

|

Figure 20. Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Bogel (Nude), 1962, batik, 86 x 40 cm. Tuanku Fauziah Museum and Gallery, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

|

-

We can entertain the possibility that these two compositions resonate with Winckelmann's recourse to European classicism as an inscription of the ideal male body as a site of freedom. How might this read against Izmer Ahmed's characterisation of the two tropes of the Malaysian figure—the dressed body and the displaced body within abstraction—as a locus of the national imaginary?[69] Against this binary is the nude body, whereby the intersecting history of European Classical aesthetic form and customary Asian artistic processes played out a different register of intimacy. One can perhaps think of Patrick Ng's strategic queering as a demonstration of accomplishment in both Western classicalism and Eastern customary aesthetics while also rendering them strange through a dislocation of these conventions of knowledge in Malaysia.

-

Moreover, the sensual charge was sited within ordinary folk, the everyday 'demos' that constituted the populace of a new country. If they were queer subjects, they were also intimating a peculiar moment. Homoeroticism can enable a levelling effect, holding the power of desire to revise the terms of hierarchy and social proscription. Similarly, as noted by Hatt in his study of a Hamo Thornycroft sculpture, 'Erotic aura was complicated by the question of labour. If the legitimacy of a conservative view of labour contained the erotic potential of the body … that erotic potential, in turn, warded off the threat of class difference.'[70]

-

However, we need to consider Winckelmann's elision of sexual difference. If the male body sites and cites individual freedom, does not this occur within a society that is already patriarchal/phallocentric? After all, perhaps the failure of Winckelmann to essentially convince emerges from his inability to truly sublimate personal erotic investments because of a dominant vision of society that could not accommodate nonstandard sexualities. Here we can recognise that difference and alterity will inevitably retreat so long as society is fundamentally organised around normative notions of difference.

-

I have also suggested that Patrick Ng's Bogel registers a foreboding of changing social mores as the decade progressed. His engagement with tradition signalled an ambivalent outcome. Tradition appeared as an imagined space capable of accommodating non-heteronormative intimacy yet such intimacy was highly contained within a small milieu, in which the fabrication of this narrative was ultimately foreclosed because tradition became a domain to map other political urgencies and hetero-normative sexual economies. Nevertheless, this reading of tradition that I have presented here demands a more nuanced understanding of its historical deployment and it resists reducing tradition to a conservative force.

-

If the process of queering signals active refiguring, this narrative achieves the staging of a struggle as one that could make objects yield specific potentialities. The recovery of queer history through the batik paintings of Patrick Ng is a letter from a not-too-distant world and that this world, albeit existing only as a small window, had made room for the staging of intimate queer desires.

Notes

[1] Harozila binti Ramli, '"Batik Painting" dan "Painting Batik" dalam Perkembangan Seni Lukis Moden Malaysia' (Batik Painting and Painting Batik in the Development of Malaysian Modern Art), PhD thesis, unpublished, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 2007.

[2] T.K. Sabapathy interviewed by D'zul Haimi Md. Zain, 'Batik Dalam Seni Lukis Moden Malaysia (Batik in Malaysian modern art),' Dewan Budaya (March 1984): pp. 47–49, p. 47. On this note, T.K. Sabapathy wrote, 'Appreciation and discussion of "batik painting" derives its concept and terminology from painting. For example, the work of art is produced, framed and hung for viewing like a painting. Its theme, motif and approach of the produced work are subjected to painterly form. Traditional batik technique is modified with the intention of complying to the rules of painting' (p. 47).

[3] Zakaria Ali, 'The batik paintings of Chuah Thean Teng,' in Chuah Thean Teng Retrospective, Penang Museum and Art Gallery, 1994, p. 25.

[4] Wang Zineng, 'Knowledge, patronage & Malayan iconography: Three aspects in the emergence of Malayan batik painting, honours thesis, unpublished, National University of Singapore, 2007.

[5] Yee I-Lann, 'Love me in my batik,' in Narratives in Malaysian Art: Imagining Identities Vol. 1, ed. Nur Hanim Khairuddin and Beverly Yong with T.K. Sabapathy, Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt, 2012, pp. 262–78.

[6] Charles Baudelaire, Painter of Modern Life and other Essays, ed. and trans. Jonathan Mayne, London: Phaidon Press, 1995, p. 13.

[7] Elizabeth Povinelli, The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy, and Carnality, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

[8] Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord, Art and Queer Culture, London: Phaidon Press, 2013; Whitney Davis, '"Homosexualism," gay and lesbian studies, and queer theory in art history,' in The Subjects of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Mark A. Cheetham, Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 115–42.

[9] Paul Franklin, 'Object choice: Marcel Duchamp's fountain and the art of queer art history,' Oxford Art Journal 23(1) (2000): 23–50.

[10] John Clark, 'Nationalism and allegories of the state: Allegories of women as symbols of national identity,' in Modern Asian Art, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1998, pp. 253–54.

[11] Geeta Kapur, 'Ravi Varma's unframed allegory,' in Raja Ravi Varma: New Perspectives, ed. R.C. Sharma, New Delhi: National Museum, 1993, pp. 96–103, p. 103.

[12] Douglas Crimp, 'Getting the Warhol we deserve: Cultural studies and queer culture,' in InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal For Visual Studies 1 (Winter, 1998), online: http://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/portfolio/getting-the-warhol-we-deserve-cultural-studies-and-queer-culture/ (accessed 13 November 2013).

[13] Mark Ledbury, 'Anecdotes and the life of art history,' in Fictions of Art History, ed. Mark Ledbury, Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2013, pp. 173–86.

[14] Universiti Sains Malaysia ? Selected list of paintings from the Sullivan Art Collection (Frank Sullivan papers, University of Melbourne). The list dates the batik paintings to 1963, the year when Patrick Ng Kah Onn mounted his first solo exhibition at the British Council, leading to an initial assumption that this was where he debuted the series. As attested by the newspaper review, the batik paintings were shown a year earlier, therefore the dating of these paintings was inaccurate. Patrick Ng Kah Onn's solo exhibition instead focused on more abstract paintings resulting from his trip to India, which was part of the grand prize he won at the First Southeast Asian Conference and Competition in 1957, Manila.

[15] Chermin (Frank Sullivan), 'Young artists who are setting their own style…,' in The Straits Times, 1 December 1961, p. 10.

[16] Frank Sullivan, then Honorary Secretary of the National Art Gallery of Malaysia, would go on to purchase four of these paintings. During the difficult years in the early 1970s, he would divest this set of batik paintings to the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), which was then setting up a small teaching collection for their new Fine Art programme. However, because of their depictions of nude subjects, these are no longer exhibited in today's more conservative climate.

[17] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire, New York City: Columbia University Press, 1985. Sedgwick's 'male homosocial desire' referred to all male bonds, including, potentially, everyone from overt heterosexuals to overt homosexuals.

[18] Michael Hatt, 'Near and far: Homoeroticism, labour and Hamo Thornycroft's Mowe,' Art History 26(1) (2003): 26–55.

[19] Tan Chong Guan, 'Chuah Thean Teng ~ 80 years of life and art,' in Chuah Thean Teng Retrospective, Penang Museum and Art Gallery, 1994, pp. 10–11. Chuah Thean Teng's pioneering attempt, acquiring his technical know-how largely through his initial ambition to set up a batik factory, to mass produce the fabric as a craft object for the burgeoning commercial market. Failure to compete with Indonesian export ware compelled him to reuse the raw materials when his business venture failed.

[20] E.J. Hobsbawm and T.O. Ranger, The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

[21] Frank Sullivan, 'Teng, master of batik,' in The Sunday Mail, 17 November 1963, p. 4.

[22] Very occasionally his paintings touch on the political. An example is Welcome (1967), which depicted US President Richard Nixon's unwelcomed visit to Malaysia. For a comprehensive overview of his oeuvre, see Teng: Satu Penghargaan – An Appreciation, Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, 2008.

[23] For a closer reading of the Nanyang, see Yvonne Low, 'Remembering Nanyang Feng'ge,' in Modern Art Asia 5 (November 2010), online: http://modernartasia.com/category/issue-5/ (accessed 10 November 2013).

[24] Frank Sullivan and Ungku Aziz, Teng, Master of Batik, Penang: Yahong Gallery, 1963 p. 4. Sullivan would observe, 'His themes opened up new vistas of Malayan life, not only the scene but the people and all their daily activities. Women feeding chickens, children playing, farmers gathering the harvest—all warm human, simple and everyday subjects no other Malayan artist seemed to have tackled with such relish before,' (p. 4).

[25] John Clark, Modern Asian Art, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1998. These modes were categorised as formatively identitarian/class-centred—aristocrats, plebeians and the professional artists or thematic/genre-centred—neotraditional, the avant-garde, nationalism/allegories of the state and the contemporary.

[26] Ooi Kok Chuen, 'Abundant treasures in Penang's Batik Painting Museum,' in Penang Monthly, 17 December 2013, online: http://penangmonthly.com/abundant-treasures-in-penangs-batik-painting-museum/ (accessed 2 February 2014).

[27] Judith Butler, 'Imitations and gender insubordiation,' in Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, ed. Diana Fuss, New York Routledge Press, 1991, pp. 13–31, pp. 22–23.

[28] Farish A. Noor, 'The cloth that cuts: Batik as the lingua franca of Southeast Asia,' in Batik Guild Magazine, 2011. See also Yin Shao Loong, 'The cloth that binds: Farish Noor on batik for a better Malaysia,' in ArteriMalaysia.com, 2009, online: http://arteri.search-art.asia/2009/05/13/the-cloth-that-binds-farish-noor-on-batik-for-a-better-malaysia/ (accessed 12 November 2013).

[29] For more information about the First Southeast Asia Art Conference and Competition, see Ahmad Mashadi, 'Moments of regionality,' in Crossings: Philippine Works from the Singapore Art Museum, Singapore: National Heritage Board and Singapore and Ayala Museum, 2004, pp. 27–1; Purita Kalaw-Ledesma and Amadis Ma. Guerrero, The Struggle for Philippine Art, Philippines: Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, 1974, pp. 68–69.

[30] First Southeast Asia Art Conference and Competition, Manila: Art Association of the Philippines, 1957, unpaginated. Participating countries to the Competition and Conference were not limited to Southeast Asian countries, as we know them today. Entries included works from the Philippines, Malaya, Indonesia, and Vietnam as well as from China, India, Japan and the United States. Moreover, delegates to the conference came from Australia, China, Malaya, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and the United States.

[31] Frank Sullivan, 'Malaya's National Art Gallery,' 13 July 1961, Kuala Lumpur: Frank Sullivan papers, University of Melbourne. Published in The Straits Times Annual, 1962. Frank Sullivan notes, 'In this Nirvana of peace and happiness, the artist sings a hymn praise to God for the beauty and bounty of Nature in Malaya in what is undoubtedly a masterpiece of Malayan art.'

[32] Redza Piyadasa, 'On origins and beginning,' Vision and Idea: ReLooking Modern Malaysian Art, ed. T.K. Sabapathy, Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, 1994, pp. 15–48, pp. 45–46.

33 Act 645 - National Heritage Act 2005, online: http://www.heritage.gov.my/images/akta_warisan_kebangsaan/Act%20645.pdf (accessed 10 February 2014).

[34] Zanita Anuar, 'Nasi Lemak dan Senilukis Warisan Negara (Nasi Lemak and Paintings as National Heritage),' in Senikini 1 (2009): 4–6.

[35] It was one of the few early works donated to the Permanent Collection of the National Art Gallery and formerly belonging to Mr. William Emslie, who headed the British Council in Kuala Lumpur and also served in the 'original committee' during the founding years of the National Art Gallery, Malaysia. See National Art Gallery Report ? Report of the Working Committee on Activities and Achievements from 3 June 1958 to 28 February 1963, Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, Malaysia, 1963, p. 6. Mr. Emslie however retired from the 'original committee' in March 1959.

[36] Kalaw-Ledesma and Guerrero, The Struggle for Philippine Art, pp. 68–69.

[37] Peter Harris, 'In Search of a national art,' in The Straits Times, 11 March 1958, p. 8. National Art Gallery acquisition catalogue. Acquisition date for Menyidai Kain is 1959. It was acquired from Frank Sullivan for Malaysian dollar $150. However, the work is undated.

[38] First Southeast Asia Art Conference and Competition, unpaginated. Other Malayan artists participating in the exhibition were Cheong Lai Thong, Mohd Hoessein Enas, Syed Ahmad Jamal, Tay Hooi Keat, Yong Mun Sen.

[39] Piyadasa, 'On origins and beginnings,' p. 46.

[40] Niranjan Rajah, 'Between Amok dan Adab: Expression and expressionism in modern Malaysian art,' in Bara Hati Bahang Jiwa: Expression and Expressionism in Contemporary Malaysian Art, Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, 2002, p. 42.

[41] Kendra Stepputat, 'The genesis of a dance-genre: Walter Spies and the Kecak,' in Die Ethnographen des letzten Paradieses. Victor von Plessen und Walter Spies in Indonesien. Transcript, Bielefeld 2010, pp. 267–285, online: http://ethnomusikologie.kug.ac.at/fileadmin/media/institut-13/Dokumente/Downloads/Stepputat_Walter_Spies_and_the_Kecak.pdf (accessed 12 November 2013).

[42] Michel Picard. '"Cultural tourism" in Bali: Cultural performances as tourist attraction,' in Indonesia 49 (April 1990): 37–74.

[43] Lim Eng-Beng, 'A colonial dyad in Balinese performance,' in Brown Boys and Rice Queens: Spellbinding Performance in the Asias, New York and London: New York University Press, 2014, pp. 41–90.

[44] Gary Atkins, Imagining Gay Paradise: Bali, Bangkok and Cyber-Singapore, Hong Kong and Chiangmai: Hong Kong University Press and Silkworm Books, 2012, p. 250. Atkins juxtaposes the Kecak to a present day rave party and speaks of the all-male environment that these two forms of dance created.

[45] Hildred Geertz, Images of Power: Balinese Paintings Made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1994, p. 10.

[46] Geertz, Images of Power, p. 10

[47] For example, Le Meyeur held a number of pre-war exhibitions in Singapore in 1935 and 1937, with the latter accompanied by Ni Pollok who graced the opening reception and entertained guests with Balinese dance, see the Straits Times, 27 February 1937, p. 1; The book that Spies co-authored with Beryl de Zoete, Dance and Drama of Bali, was reviewed in the Straits Times, see 'Book of the week: Fine descriptions of the dances and dramas of Bali,' in the Straits Times, 12 February 1939, p. 11; This fascination with Bali was further renewed in the post-war years with the four Singapore artists' Trip to Bali, an event and exhibition that cemented Bali as a central imaginative resource and wellspring for the Nanyang imaginary, see Trip to Bali: Liu Kang, Chen Wen His, Chen Chong Swee, Chong Soo Pieng, exhibition catalogue, 1953.

[48] Attendance to that exhibition was recorded at 5,900. See National Art Gallery Report, pp. 4–5. Other exhibitions held at the National Art Gallery included: The Art of India, Old and New (1959), Twentieth Century Highlights of American Painting (1959), Modern French Art (1959), Art of Vietnam (1960), Exhibition of Aborigine Art (1960).

[49] Piyadasa, 'On origins and beginning,' p. 45.

[50] Ooi Kok Chuen, 'Once upon a time in Malaya' in ArteriMalaysia.com, June 2006, online: http://arteri.search-art.asia/2009/06/27/once-upon-a-time-in-malaya/ (accessed 13 November 2013).

[51] See, 'The bigger the batik the better,' in the Age, Tuesday 11 November, 1969, p. 18.

[52] 'Di-pameran manifestasi dua seni: Dua orang pelukis wanita turut ambil bahagian (At the manifestation of two arts: Exhibition included works by two women artists),' in Berita Harian, 14 April 1970, p. 6.

[53] Ooi Kok Chuen, 'Strokes of wry humour,' in the Sunday Star, 26 April 1998, online: http://www.viweb.freehosting.net/PatrickNg.htm (accessed 15 November 2013).

[54] Anurendra Jegadeva, 'A tiny Jamal, A huge Gunawan and everything in between,' in Favourites from the Zain Azahari Collection, Kuala Lumpur: The Edge, 2013, p. 15.

[55] Jegadeva, 'A tiny Jamal, A huge Gunawan and everything in between,' p. 15.

[56] Izmer Ahmed, 'Tracing the mark of circumcision in modern Malay/sian art,' PhD Thesis, University of Victoria, 2008, p. 175.

[57] Izmer Ahmed, 'Tracing the mark of circumcision,' p. 174. For Izmer, the metaphorical mark of circumcision was seen to have been 'a significant trope underlying the themes of the graphic mark in the production of ethno-religious and national identities' (p. 174) for Malaysians of Malay descent with Islamic affiliation. His focus was however on post-National Cultural Congress of 1971 Malay/sia identities where bodies are collected under the mark of Islam to tackle the dislocating effects of modernity.

[58] Izmer Ahmed, 'Tracing the mark of circumcision,' pp. 142–43,

[59] Ooi Kok Chuen, 'Strokes of wry humour.'

[60] See Neil Manton, The Arts of Independence: Frank Sullivan in Singapore and Malaysia, Canberra: Neil Manton, 2008, p. 56.

[61] Ooi Kok Chuen, 'Strokes of Wry Humour,' pp. 4–8

[62] Manton, The Arts of Independence, p. 85.

[63] Manton, The Arts of Independence, pp. 73–122.

[64] Anthony Appiah Kwame, 'Is the post- in postmodernism the post- in postcolonial?' in Critical Inquiry 17 (1991): 336–57, p. 353. Kwame notes, 'Postrealist writing, postnativist politics, a transnational rather than a national solidarity.… Postcoloniality is after all this: and its post-, like that of postmodernism, is also a post- that challenges earlier legitimating narratives' (p. 353).

[65] Whitney Davis, Queer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and Beyond, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010, pp. 23–50.

[66] Whitney Davis, 'Winckelmann divided: Mourning the death of art history,' in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, Second Edition, ed. Donald Preziosi, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 35–44, p. 36.

[67] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, trans. Henry Fusseli, London: A. Millar, 1765, p. 2. 'There is but one way for the moderns to become great, and perhaps unequalled; I mean, by imitating the ancients' p. 2).

[68] Syed Ahmad Jamal, Seni Lukis Malaysia 57–87, Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, p. 50. Abstract painter turned curator/art historian Syed Ahmad Jamal's broad observation of this period might have hinted at such aspiration, 'Malaysian artists were not looking back to history. There were no national archetypes to relate to. The art scene was devoid of any awareness as historical stepping-stones … tradition was being created then and there.… The by-word was Malaysian Art starts now' p. 50).

[69] Izmer Ahmed, 'Tracing the mark of circumcision,' p. 116.

[70] Hatt, 'Near and far,' p. 51.

|