Looking Out: How Queer Translates in Southeast Asian Contemporary Art

Iola Lenzi

-

Contemporary art in Southeast Asian has recently begun to come into focus as a field of scholarship, with discourse derived from criticism and curated exhibitions, amongst other sources, that explore the art of recent decades on its own contextual terrain.[1] Emerging from the study of art from the 1970s is an understanding of an oeuvre informed by and centring on social conditions, even as the notion of regional art has expanded in terms of geography. Politics, history, individual-versus-state relationships, and the tense interplay of personal, group and national identities are examined critically by artists throughout the region. Indeed, visual practice and identity have been closely associated in Southeast Asia?s nation-building strategies as art is engaged as a driver of individual empowerment and social change in order to oppose authoritarian states that see social pluralism as threatening.[2] But in Southeast Asia, unlike European and American contexts, civil society is immature or non-existent and expressions of sexuality and ideas of identity can operate in relatively discrete and surprising ways. As Southeast Asia strives to move on from its autocratic post-colonial past, citizens push for individual and collective emancipation. On this ground of rapidly shifting power structures and in regard to recent platforms of freedom, erotic iconographies and gender play already manifest in Southeast Asian traditional culture can function as vectors of resistance.[3] Because notions of gender and sexuality can singularise a field, what does 'queer' mean in such a framework vis-à-vis the contexts of Southeast Asia?

Queer in Southeast Asia: A contextual appraisal

-

The scrutiny of queer, understood here as non-heteronormative, in artistic practices of Southeast Asia calls for a brief examination of the historical constructs of non-heterosexuality in the region. This examination necessarily includes the search for the origins of a more recent local hostility to queerness. Finally, a discussion of queerness and art in Southeast Asia cannot be separated from the region's current poor standards of human rights.

-

Transsexualism and homosexuality were traditionally commonplace in Southeast Asia. The historian Benedict Anderson noted the banality of homosexuality in the East Indies with his analysis of Indonesia's ancient epic prose volume Centhini bringing to light its normalcy in Javanese sexual culture. Anderson writes, 'Male homosexuality at least was an unproblematic, everyday part of highly varied traditional Javanese sexual culture…. [Centhini] includes, inter alia, detailed descriptions of sodomy, fellatio, mutual masturbation, multiple partner intercourse, and transvestitism. Heterosexual sex is described in exactly analogous ways.'[4] However, Anderson goes on to discuss the appalled reaction of nineteenth-century Dutch officials and missionaries to local sexual practices in Javanese society, described by the Europeans as 'the natives' incorrigible addiction to pederasty and sodomy.'[5]

-

Java's attitudes to sexuality may not have been universally shared throughout the vast and culturally diverse region now known as Southeast Asia. However Anthony Reid has referenced sixteenth-century writings describing homosexuality in Burma as well as historical documents attesting to Southeast Asia's regard for the body as a centre of beauty, confirming that nudity was not taboo until the colonial period.[6] Documents further reveal the region's pre-modern absence of views on sexuality, queer sexuality if not necessarily generalised, not possessing any particular moral connotation due to sexuality's place as a private business outside religion's purview or, when queer, part of mystical belief.[7]

-

The Christian world's history of antagonism to homosexuality is not the subject here but, for the purpose of this essay, queerness as a non-normative identity must be appraised in the context of societies that have adopted Abrahamic moral codes. In the context of Southeast Asia in modern times, this means principally Muslim- and Christian-dominated areas. And although Peter A. Jackson disputes the conventional notion of Thai Buddhism's tolerance of homosexuality, his view, nuanced in any event, relates to modern Thailand rather than the pre-modern.[8] In Southeast Asia, opposition to homosexuality can thus be understood as a relatively recent and unevenly practiced mode of power.

-

Or, in a word, queerness in the region today, even modern and post-colonial Southeast Asia where Abrahamic moral prescriptions can be the norm, cannot be understood in terms European and American 'models.' Queer's self-conscious relativism and resistance to dominant norms must be seen as doubly relative in a part of the world where religious syncretism, vestiges of animism, and gender-play remain part of the social fabric. This is not to say that Southeast Asia is a queer haven. Statutory discrimination against homosexuality, often a hangover from colonial times, remains in place, notably in Singapore and Malaysia.[9] Indeed, one of the region's most notoriously provocative artistic actions of the last twenty years was Josef Ng's performance Brother Cane (1993) that contested discrimination against gay men in Singapore.[10] The Southeast Asian context is therefore paradoxical with many influences coming together to form a framework for local contemporary sexual cultures: ancient tradition's normalised sexual plurality; the conservatism and Christian prudishness of residual colonial-period laws; strains of conservative Islam imported in recent decades; centralised systems of authority that distrust manifestations of individualism or assertions of minority statuses; and, moreover, the young, internet-savvy population's awareness of global culture and mores, among other influences.

-

The last thirty years have marked a turning point in Europe and America as LGBTQ rights, in tandem with the women's movement, have gained momentum. Both emerged as counter forces and the drive for LGBTQ rights was arguably facilitated, according to Yvonne Doderer, by urbanisation and other aspects of urban geography and social structures.[11]

-

In Euramerican contexts, ideas of gender, sexuality, art and culture have evolved in content and scope in recent decades. As writings have proliferated, queer has been integrated into broader discourses; and queer politics has come to encompass a wide array of concerns beyond feminist and LGBT social movements. While earlier texts may have defended the specific relevance of homosexuality to western cultures, later formulations moved queer into less narrowly-defined arenas of study.[12] But even as the assertion of queer culture as a contestation of gender and sexual normativity, untidy by nature, has morphed into a tool of critique beyond identity, in Europe and America ideas of queer still harbour a flavour of counteraction that has less raison d'être in Southeast Asia.[13] In those contexts queer resistance has involved battles about the recognition of homoerotic imagery that figure throughout Occidental art history from the Greeks onward and hence the teaching of a lesbian and gay art history. In a 1992 essay on art history and sexuality, the art historian Whitney Davis gives an account of his 1991 struggle to present a lecture on the homoeroticism of ancient Greece as a means, among other aims, of teaching about homosociality in that era.[14] Such a battle is today mostly outdated in western academia as same-sex iconographies are integrated into the study of visual culture. In Southeast Asia, conversely, despite the rise of fundamentalist Islam in Indonesia, the Centhini, with its vividly 'queer' descriptions, remains recognised as a foundational work of culture.

-

The literature and practices of queer culture that have grown since the early 1990s now encompass a vast, mixed, and often contradictory pool of ideas. But if the 'field' is more plural in outlook and, as articulated by Michael Warner, now underpinned by philosophical and ethical tenets which are humanistic in thrust and serve more than as a counter to heterosexual bias, could queer on these terms resonate in the Southeast Asian art world? [15] Warner's perspective on queer as an inclusive critical stand is not necessarily a poor fit but Euramerica's three-decade genealogy of queer, so different to Southeast Asia's, argues for a locally nuanced analysis for Southeast Asia.

-

Untangling the many notions and sub-notions of queer studies is not the object here but let us return to Davis and his musings on early western art historical writings by the Occident's first art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Davis discusses the German scholar's weighing of civic liberty and social-sexual licence in the Greek world.[16] If in Euramerica queer discourse has evolved in recent decades, over this period basic freedoms have not been in question; or, in an environment where human rights are enshrined, the defence of queer culture has the quality of a battle on the moving ground of ideas that are often related to the quick-sands of morality.[17] However, in Southeast Asia basic human rights are not a given and this same battle is framed within a larger conversation for physical survival and political voice.[18]

-

For the reason of greatly diverging human rights contexts this paper explores art by openly queer regional practitioners rather than manifestations of gender politics in Southeast Asian art. A second reason for my approach, as pointed to above, is Southeast Asia's only relatively recent reaction, in some areas, against 'deviant,' non-conformist sexuality. Human rights are imperfectly protected in Southeast Asia and thus queer-ness is one of many vulnerable minority statuses. Do queer artists of Southeast Asia use their practice to address such a status? If so, against what? Are there connections in Southeast Asia, as there was a generation ago in Euramerica, between queer artists and art defending non-heterosexual critical issues? If it can be noted that Europe and America saw a shift from an earlier critical concern with gender politics to today's wider discourse on queer (which has segued to critiques of systems that are normative by definition), it can be understood that artists in Southeast Asia can be considered 'queer' for different reasons. And one reason is that while sexual diversity was accepted historically, freedom of expression is typically repressed. This essay discusses art by openly queer practitioners to observe how their works may be characterised, possibly appearing as manifestations of social consciousness in the face of autocratic systems; and nurtured on local soil away from queer's western-centric evolutionary morphology of recent decades.

Gender cross-overs and erotic iconographies in Southeast Asian contemporary art

-

Assuming that art by queer regional artists is generally contestative, it is useful to recall selected traits of local contemporary art's critical grappling with power, its questioning of social exclusion and the visual integration of icons of gender and sexuality.[19]

-

The links between contemporary art and social change in Southeast Asia have been under investigation since the 1990s.[20] Even while the writing on Southeast Asian contemporary art is still in its infancy, this art's socio-political inflection can be accepted as canon-characterising. For the purposes of this study this linkage is understood as established.

-

Sexual and gender totems occupy a place of predilection in contemporary Southeast Asian art with practitioners deploying iconographies alluding to the erotic as a means of articulating plural discourses. This particularity can arguably be traced,in part, to the relative autonomy of women in pre-modern regional history. Reid asserts that, unlike their peers in China and India, the region's women were economically important, enjoying a prominent role in trade and dominating the family's financial affairs. Their status has also been ascribed to animism's celebration of women assimilated with life energy, the region's labour-intensive rice-planting culture, contraception, and Malay matrilineal custom, among other reasons. This context fostered a sexuality that afforded pre-modern women power and was free of the inhibitions of chaste Christian Europe.[21] This mutual respect and power balance between the sexes in ordinary, non-courtly life would thus be reflected by Southeast Asian contemporary art's frequent gender-neutral activation of signifiers of the body and the erotic.[22] In turn these compelling erotic signs, legible across cultures, open works up to diverse critical avenues.

-

In this regard the study of Southeast Asian art from the 1990s onward reveals male and female artists using a plethora of sexual references as well as gender ambiguity to negotiate, in coded ways, issues that are socially or politically off-limits. Examples include: Javanese artist Heri Dono's late-Suharto period Flying Angels (1996) that embodies political dissent through the installation's androgynous and campy winged figures; Hanoi's pioneer of contemporary art Vu Dan Tan's Amazon series of female warrior armour made from silhouetted metal that suggest an equivocal mixture of flirtatious femininity and danger but claim a stance on individualism and independence. To be worn, yet threateningly razor-sharp, this work cloaks resolute defiance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vu Dan Tan, Amazon series, cut-out metal armour, 2001–2009. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2011

|

Nindityo Adipurnomo's ongoing explorations of Javanese rituals permit a conflation of male and female perspectives that track the evolution of ideas of gender identity and cultural metamorphoses in late-twentieth-century Indonesia and are offered as social critique (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nindityo Adipurnomo, Portraits of Javanese Men series, digital photography, 2001–2004. Source: Cemeti Art House (CAH) Indonesia and Nindityo Adipurnomo

|

Bangkok's Pinaree Sanpitak's breast-stupa-cushion installation noon nom is simultaneously lascivious and nurturing and is as much about power, materialised by the breast's life-giving expression, as about a sense of womanhood that advocated freedom and empowerment for all (Figure 3).[23]

Figure 3. Pinaree Sanpitak, noon nom, interactive cushion installation, 2002. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2011

|

-

Singaporean Suzanne Victor's overtly feminist works of the 1990s have morphed into kinetic pieces that leave behind clan-specific readings and engage on ideas about identity and power in nation-building in Singapore and Southeast Asia but with universal implications. Indonesia's Arahmaiani also starts with feminist ideologies but then broadens to a probing of liberty, communalism, and syncretic Islam among other interests; in one work, the audience is invited to take refuge under a giant mixed-sex burqa of patchwork silk.[24] Hanoi artists Truong Tan and Nguyen Van Cuong, with their Mother and Son performance, and Nguyen Van Cuong, Nguyen Quang Huy and Nguyen Minh Thanh's many representations of woman (alternately dominatrix, sex-object, farmer or mother-earth) aim to expose social tensions surfacing in rapidly modernising Vietnam (Figure 4).[25]

Figure 4. Nguyen Van Cuong, My Mother is a Farmer, ink and pigment on do paper, 2002. Photograph provided by the artist, Nguyen Van Cuong

|

-

This selective tour of already well-documented regional artworks suggests that the gender politics and their divisions that have been part of Euramerican culture since the 1970s are less apparent in Southeast Asian contemporary art discourse, especially outside Singapore and the Philippines where practices are more closely aligned with dominant trends in Europe and America. In Southeast Asia at the turn of the century it can be argued that some male practitioners, like their female counterparts, made art that if not feminist in the doctrinaire sense evokes the centrality and potency of woman as a means of infiltrating other topics.[26] And as gay rights advocacy becomes increasingly mainstreamed, even in Southeast Asia's more politically and socially conservative centres, we may further ask how queer artists steer their vision.[27]

Queer Southeast Asian artists' view of power and the individual: A distinct perspective?

-

A comprehensive survey of the region's queer artists' works is beyond the scope of this essay. Yet through the analysis of selected pieces, chosen for their art historical significance within Southeast Asia, a search for possible common conceptual approaches and themes is feasible. From this analysis, a sense of the forms of the relationships between queer Southeast Asian artists and their production of art may emerge.

Individual versus group: Expressions of personal identity as a barometer of freedom

-

Some of the earliest examples of homoerotic imagery in regional contemporary art came from Vietnam's Truong Tan.[28] The first openly queer artist in contemporary Hanoi, Truong Tan's output of the 1990s—multi-media and performative—is often explicit: erect penises, golden showers, blindfolds, rope and other bondage paraphernalia. Occasionally he employed text such as in the series Here Very Dark (1995), and always exhibits a confident claim to queer sexuality (Figure 5).[29]

Figure 5. Truong Tan, detail Here Very Dark, ink on do-paper, series, 1995. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2011

|

-

'With two decades hindsight, and seen against the backdrop of emerging Southeast Asian art histories, how do these paintings and multi-media works play out art historically? Certainly, they are important as Vietnam's first sexually-emancipated images in terms of the current era. But, in addition, their layered readings provide them canon-shaping status. Even in Hanoi today, Truong Tan's evocation of gay sexuality remains audacious. And though viewers from the earlier period were not necessarily perturbed by the paintings' stylised narratives of same-sex love-tussling—particularly the artists and intellectuals who frequented relatively liberal environments such as Hanoi's private space Salon Natasha where Truong Tan's art was shown from 1993—there is the works' lasting ability to trigger critical thought on collective ideologies (Figure 6).[30]

Figure 6. Truong Tan, untitled, ink on do paper, circa 1996. Image provided by Natalia Kraevskaia

|

-

Indeed, in 1990s Hanoi, the exposure of personal identity remained in radical opposition to group identification and may therefore be perceived as provocative. Truong Tan's icons, however abstracted into linear figures (compared by some to Keith Haring's icons though the artist would not have had much exposure then to the New York artist's imagery save through a few reproductions), speak for the individual and their frequent captions detail personal experiences.[31] In the context of Communist and socially conservative Vietnam they serve to advance the cause of the individual outside the group. This credo, though radical, would have escaped the eye of the censors because of Truong Tan's innovative graphic language and the ephemeral nature of his performance.[32] Truong Tan's forceful advocacy of the individual's freedom through queer emblems also had influence on his students. The artist was a lecturer at Hanoi's University of Fine Arts where he taught Nguyen Minh Thanh, Nguyen Quang Huy and Nguyen Van Cuong who are now, along with their teacher, recognised as central figures of the Hanoi 1990s avant-garde.[33] The first went on to revolutionise the portraiture of familial ties in Vietnamese art—his intimate gaze revealing psychological tensions that construct intra-family bonds in a way no artist had ever before explored in Vietnam.[34] Nguyen Van Cuong, with his transgressive sexual language, produced Vietnam's first explicitly socio-political works. From Truong Tan these artists learned the power of art as a tool to provoke critical thought.

The individual and public space

-

In Truong Tan's paper works, performances, and installations of the 1990s, protagonists are individualised and brought to life through intimate and often obscene language: 'Here, it's too dark. I can't see. I step on shit. Fuck, Fuck, Fuck.'[35] As remarkable as his imagery's erotically risqué flavour is—literally and metaphorically—it is the tense anger and sense of hostility that captures the artist's interest in opposing group identification. To decrypt this tension in its original context, and noting the artistic subject's overt outsider status, is to decode Truong Tan signs as targeting the repressive strictures of Vietnamese society in all spheres. Though emerging from personal experience, his works' primary interest in queer-ness leads audiences towards a subversive critique of governing systems in the lives of Vietnamese; and with his seductive linear drawings, Truong Tan invites viewers to contemplate an alternate construct. Galvanising but not gratuitously pornographic the work is bristling with sexual energy that speaks to diverse audiences. Though manifestly homoerotic, it is the erotic electricity, not the queer specificity of these works that shouts and discloses a subtext of general contestation and a drive for freedom. Also Truong Tan's formal co-opting of socialist propaganda-poster style delivers an irony-filled jab to the regime. The overt queer sexuality pictured by him in 1990s Vietnam-nudes, prohibited since the Communist Revolution, were still problematic—can be construed as an opposition to authority. Because the Communist Party, even post-'doi moi,' remains the principal determinant of social regulation Truong Tan's art reads as an act of defiance confronting the political monolith.

-

Truong Tan's queerness and criticality are doubtless related. But other artists in 1990s Vietnam show criticality though they are not queer as such. Hanoi's Vu Dan Tan and Nguyen Van Cuong also produce an art of opposition. They too are arguably outsiders and therefore sensitive to the injustices and exclusions of authoritarianism. They too encroach on public zones—physical and intellectual—and avow individuality. Like Truong Tan, these artists enlist sexual iconographies and eroticism in order to subvert visual, material and semantic codes. Indeed Nguyen Van Cuong's sexually charged narratives can be more violent and disturbing than Truong Tan's.[36] The use of nudity, sexual emblems, and explicit sado-masochistic references claim a drive to appropriate public places dominated by discourses of authority. This is further compounded by these artists' infiltration of public spaces via performance, sound/music productions and murals, all of which call on audience participation and reception for meaning. Installations also recall the public's clash with authority: for example, Vu Dan Tan appropriated street vendors' boxes for his influential Suitcases of a Pilgrim series (1994–2009). The conquest of the public arena is also realised through the body itself and can raise issues about violence. Examples of such in Southeast Asia include iconic names such as Lee Wen, Tang Da Wu, Vincent Leow, Gilles Massot, FX Harsono, Tran Luong, Amanda Heng, Josef Ng, Bui Cong Khanh, Arahmaiani, Jason Lim, Melati Suryodarmo, Vasan Sitthiket, Moe Satt and Po Po. Melati Suryodarmo, Jason Lim, Tran Luong, Vasan, Bui Cong Khanh and Josef Ng are all particularly notorious for their discomforting pieces.

Queer-ness and violence in Southeast Asian performance art

-

It is revelatory to review performance pieces by Saigon-based queer artist Bui Cong Khanh that interrogates Vietnamese social and political constructs of the last decade. Though of the same generation as some of the aforementioned Vietnamese artists, Bui Cong Khanh became active some years later and his critical practice emerged in the noughties. Comparable in his forthrightness to the politically vocal Nguyen Van Cuong, Bui Cong Khanh, through his scrutiny of the nation's urban and rural social landscapes, dissects cultural habits in order to target paradoxes that surface when traditional rural society undergoes radical and fast-paced transformation. But where Nguyen Van Cuong is alert to tensions arising from decay brought by corruption, mass culture, and lust for power and money, Bui Cong Khanh trains his eye on the exclusion of individuals and groups operating from within and outside official structures and institutions. In his Stamp on Me (2003) performance, first executed at Blue Space Gallery in Saigon, the artist proposes his body as the battleground for a dispute between public and private arenas. As anonymous members of the crowd stamp his naked torso with an official-looking seal that spells out either 'yes' or 'no,' they reproduce the mechanical gesture of the mindless state-bureaucrat allowing or disallowing a petitioned request. A measured tempo may then escalate as the strangers' controlled arm movements evolve into frenzied assaults and incite reflection on the psychological brutality of random decision making and abuse of power.

-

It may be tempting to conclude, when comparing Stamp on Me with Josef Ng's Brother Cane (1993) that the works' violence is a consequence of Josef Ng's and Bui Cong Khanh's respective queerness. But refuting this cause-and-effect linkage are several performances by non-queer regional artists that offer up the body to brutality, Melati Suryodarmo's ongoing I Love You and The Ballad of Treasures (2004) and Tran Luong's Red Scarf/Welts (2007) come to mind. Indeed Stamp on Me may have been a harbinger of the latter. In Stamp on Me the artist is observed somatically as the centre of action but not himself acting, so he is identified as both agent and outsider/audience. In the context of single-party-Communist Vietnam this performance of a random 'yes-no' leads to a critique of a de-humanised state; but in its formal and conceptual strategies that allows public participation it reveals a Southeast Asian typology. Further, in resonating beyond national or political specificities, the piece is universally legible in its unmasking of the opposition of individual and collective interests.

-

As in the example of Truong Tan, his use of his body as a stage is not about queer hedonism but rather public accessibility, articulating with immediacy the shift between perpetrator and subject of violence, and ultimately suggesting the volatility of identity as insiders swap places with outsiders (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Bui Cong Khanh, Stamp On Me, performance, 2007. Image by Bui Cong Khanh, 2011

|

Fiction and reality: Altering positions

-

A second work by Bui Cong Khanh, made a decade later, retains the artist's stand of solidarity with the marginalised. The tri-part Saigon Slum (2012) juggles truth and illusion, a tension established to heighten core ideas about Vietnamese social control and those who challenge it. The installation is a doll-house-style shanty-town, a miniaturised reconstruction of a Saigon shack, home to the poor and job-questing migrants from Vietnam's countryside. Handmade by the artist, the model unites two opposites: its refined workmanship pointing to contented domestic ease while referencing the uncertainty of life within. With this shuttling between extremes, the artist draws the audience into a critical discourse regarding the failed promise of state-sponsored egalitarianism represented by Communism and, more broadly, marginality within rigid social structures pervasive in Southeast Asia. For Bui Cong Khanh, the population of the inner-city zone is marked not only by its poverty, but also by its identity, its inhabitants are outsiders who in their administrative untidiness (many may not be officially registered Saigoners) and refusal to comply with authority, embody resistance.

-

Compounding the work's dual insider/outsider perspective, and its ambiguous slide back and forth between reality and art, Khanh installs a closed-circuit television monitoring system in the exhibition space that tails viewers as they inspect the piece, projecting them onto TV screens in real time. The looker is hence observed and filmed, this shift of view-point positioning the audience as both subject and voyeur. In this way Saigon Slum, with its unending exchange between fiction and truth, and its interchanging viewer roles, sometimes controller, sometimes controlled, is simultaneously destabilising and compelling, its visual magnetism harnessed to illuminate the stresses at the heart of contemporary existence.

-

Bui Cong Khanh's queerness has led him to experience difference yet he asserts he has not suffered homophobia and does not know of anti-queer violence in Vietnam.[37] He is clear about his broad-based reach and the dangers of a herd mentality and social exclusion everywhere.

Making my work I don't think about my sexual orientation. There are big problems in Vietnam and the world today, I think about those. Being gay in Vietnam is one of many minority statuses. Everyone outside the Communist Party experiences this, the feeling of exclusion is not much different for us all, queer or not. I am more interested in a spirit of solidarity than in a splintering off toward difference. In Vietnam we can't say things directly and to oppose the system, we must stand together.'[38]

History as a critical arena

-

Openly queer Dinh Q. Le grew up in the United States after his parents fled the Vietnam-Cambodia border region in the wake of the Vietnamese advance on Cambodia that toppled the Khmer Rouge in 1979. Like Bui Cong Khahn and Truong Tan, he has developed works that if located in the self, also expand to search areas where audiences follow and are challenged.

-

Central to Dinh Q. Le's art is its mining of history and memory; the artist's view informed by his childhood in rural Vietnam, the war, life as an émigré on the American West Coast, and his return to Saigon in the 1990s. Through his practice Dinh negotiates cultures, geographies and perspectives. Yet even if concerned with history, it is not nostalgia that grounds his work but instead his thoughtful allowance of past into present and its consequences of loss, flight, instability, transformation, healing and renewal, as conceptual, thematic and formal supports. Employing an array of media, the artist has a particular penchant for large-scale installation and photography. His woven photographs are especially distinctive for their quiet translation of polarity and pathos through their broken and reconstituted images—both tangible and metaphoric. Over the course of two decades, Dinh Q. Le's creation has been characterised by its humanism and promise of redemption.

-

Dinh Q. Le's practice adopts a changing viewpoint that alternately positions the viewer as actor, witness and subject. Subjective and objective reality are thus interchanged, this play with certainty taking tangible events such as war, separation and death onto a philosophical plane. Formally, this multi-stranded perspective is implemented through strategic uses of archival material such as photographs of victims of the Khmer Rouge in The Quality of Mercy (1996); the excavation of Vietnam War cinematographic footage in The Farmers & The Helicopters (2006); or war drawings from Light and Belief (2012). Interviews too can underpin creative productions, such as those included in this work. The seeking of the individual in the group connotes personal independence and is counter to the Communist state.

-

In some instances Dinh Q. Le shifts his gaze in time while in others he changes location as well as era, displacing the vantage point so that, for example, the people of photographic portraits of the victims of the Khmer Rouge become actors rather than subjects.[39] The Quality of Mercy is more than a commemoration of the slain or a condemnation of evil. Neither sensational nor voyeuristic, the installation reveals the artist re-thinking history by altering the position of victim and interrogator, quizzing the viewer on his or her identification with the work's protagonists. For here the murdered dominate, physically and psychologically, and as audiences penetrate the space, through this oscillating perspective they are made to conjure troubling questions of responsibility and ethics. Shying clear of the didactic, through artistic process and altered viewpoint, The Quality of Mercy permits these dead Cambodians to transcend the passivity of victimhood and speak to the future. Further, deliberately muddling viewer rapport with victim and perpetrator, Dinh Q. Le effectively co-opts audiences to the falsehood of concepts of loss and gain in history. Though beginning in Pol Pot's Cambodia, he shows how history is fluid and changing as opposed to a fixed entity. Dinh Q. Le's art's audience-engaging humanism and articulation of flux are the essential threads in his work. He says,

I have never thought about myself or my work in that way or from that perspective (the queer agenda). I am openly gay and interested in so many topics. Whether in America or Vietnam, I feel I exist on the outside. This in-between status has given me independence and critical distance that has provided me total artistic freedom.'[40]

Convention and cleavage: Probing disconnections

-

History again occupies a prominent position in the works of Michael Shaowanasai and Jakkai Siributr. Are their critical readings of nationalistic discourses and state institutions linked to the artists' queer identity? Possibly, but many regional artists probe history as the origin of rigid pillars of nation, so incompatible with individual voice.

-

Moving between time spectrums, proposing alternative pasts, challenging conventions of national identity, mixing and distorting iconographies and their frames of reference, alluding to contentious socio-political splits excised from the history books, and generally querying rather than stating, works by Shaowanasai and Siributr underscore the Kingdom's discordant reality.

-

To consider Shaowanasai's practice through the prism of gender politics because of the fame of his camp 2003 musical-action spoof The Adventure of Iron Pussy is to misconstrue his wider mission for which he plunders the layered conceptual possibilities of gender subversion. Shaowanasai, though often starring in his drag-posed performative photography, does not put cross-dressing at the centre of his art. Rather, he presents himself in drag to construct an argument on different topics: the fate of Thailand today, the monarchy, corruption in the Buddhist Sangha, and more generally how mainstream discourses and boundaries impact on the individual. He uses the personal, among which is his own body and sexuality, less for the sake of autobiographical spectacle, or formalism with a secondary reading as a critique of popular culture than as a means of looking and speaking out about pressing collective issues. For anyone tempted to neglect the primacy of socio-political intention in Shaowanasai's work, it is significant to recall the artist's command of a broad array of media and approaches that do not involve the body as dramatic field, or indeed any reference to gender, such as the installation Buddha, Dharma, Sangha (2006), King & Queen diptych (2006), or The Untouchables (2013 and 2014).[41] The common thread running through the artist's oeuvre is not vestimentary transgression but rather conceptual play as a tool for bringing to light the vagaries of life in the nation (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Michael Shaowanasai, Portrait of a Man in Habits no. 1, C-print, 2000. Provided by Michael Shaowanasai and used with his permission

| |

Figure 9. Michael Shaowanasai, Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, installation, 2007. Provided by Michael Shaowanasai and used with his permission

|

-

Jakkai Siributr's affiliation with textiles, in a non-Asian context, might peg the artist as feminine or queer.[42] But such clichés of discourse have no place in Southeast Asian contemporary art marked so emphatically by its openness to all media, materials and techniques—a diversity emblematic of the field. There is no room here for an extensive review of the high/low art problematic that befalls Southeast Asia after the arrival of colonial academic art teaching in the early twentieth century. However contextual examination reveals that regional contemporary art's material repertoire is not gender inflected. Textile, knitting, sewing, tapestry, rattan, straw, lacquer, paper, porcelain and other 'soft' or 'craft' media are gender-neutral in Southeast Asia where they are universally selected.[43] Siributr's practice is exemplary of such regional attitudes and as I have previously argued, this diversity does not qualify Siributr as a 'textile artist,' but rather as someone who at times utilises the specific attributes of sewing, fabric and embroidery to further his precepts.[44] These, as with many Thais, revolve around the Kingdom's polarised social, cultural and political landscape.

-

Installations such as Evening News (2011), Rape and Pillage (2013), Transient Shelter (2014) or 78 (2014), examine the tensions cleaving Thailand with a mind to countering public apathy and indulgent attitudes toward established systems. Siributr's art is all the more successful for its material familiarity, its cloth component, associated with local ritual and tradition, aiding the translation of layered and contentious ideas to a broad public.[45] In Transient Shelter, as in Rape and Pillage, appropriated uniforms serve to reference the Kingdom's power structures as embodied by the civil service, police and army, the last presciently meaningful after the recent 2014 coup. While in the first installation the white outfits loosely evoke parliamentarians, and so the failure of Thai democracy, in the second the official garb is playfully adorned with invented tokens of glory. Siributr is thus interrogating and challenging the meaning of rank and social strata in an ossified Thai system that is unable to respond to the people's needs due to the weight of convention and tradition. Through references to the body, the performative aspect of costume calls forth audience reaction, and the uniform is suggestive of social transformation. In these two oeuvres that play with image and reality Siributr posits fiction and truth as confused and interchangeable in contemporary Thai society. The artist states:

My art is shaped by who I am. I am not an activist but do have grave concerns about my immediate surroundings and current social disfunction. My sexual orientation or other gender issues are not much of a preoccupation compared to the bigger issues that Thailand is facing now. These problems need defending more urgently and though the law doesn't reflect this, Thailand is quite tolerant when it comes to LGBT agendas (Figure 10).[46]

Figure 10. Jakkai Siributr, Transient Shelter, installation, 2014. Image courtesy of Tyler Rollins Fine Art New York

|

-

Maitree Siriboon is from Thailand's impoverished Northeast Isan region that is often opposed to rich Bangkok. Through his multi-media practice Siriboon explores the rural-urban schisms that numerous regional artists have exploited as an entry point for wider critical social and cultural discussion.[47] The theme is a persistent one, explored particularly by Thais and then later, Vietnamese. In 1982 Chalood Nimsamer's ritual-inflected performative Rural Environmental Sculpture allusively sketched out his critique of Bangkok's cultural and political centralisation. Subsequently, Montien Boonma created his A Pair of Water Buffaloes (1988) and the following year put up his Story from the Farm exhibition commenting on the fast-accelerating urban-rural disconnect in the Thai context.[48] In the 1990s, as urban development exploded and Bangkok experienced an unprecedented building boom, Boonma assembled his iconic Venus of Bangkok and Vasan Sithiket his 1995 Committing Suicide Culture: The Only Way Thai Farmers Escape Debt (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11 Montien Boonma, Venus of Bangkok, installation, Singapore Art Museum (SAM), 1991–1993. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2011

|

Figure 12. Vasan Sitthiket, Committing Suicide Culture: The Only Way Thai Farmers Escape Debt, installation, Singapore Art Museum (SAM), 1995. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2011

|

-

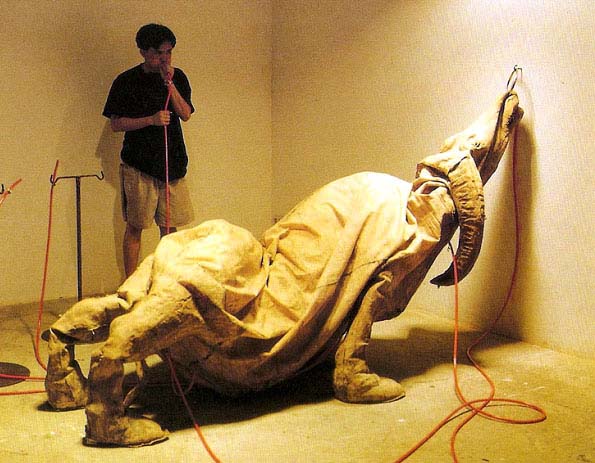

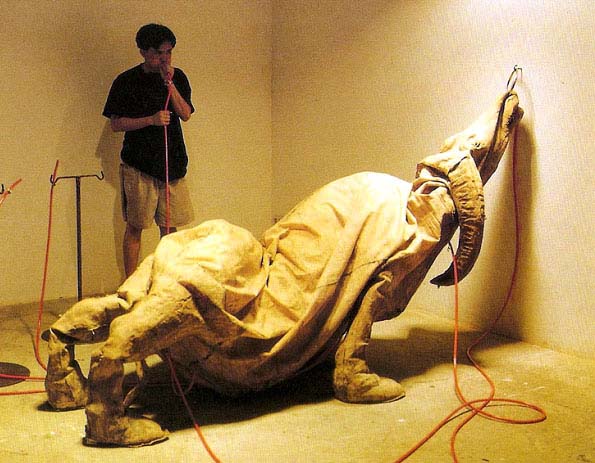

In the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis, sparked in Thailand in July 1997, Sitthiket conceptualised his 1998 Farmers are Farmers multi-media exhibition in Bangkok. Also responding to the crisis, in 1998 Sutee Kunavichayanont produced his interactive blow-up latex buffalo installation The Myth from Rice Field (Breath Donation). The latter activates audiences to take charge of their own economic and cultural destiny, the inflated/deflated up-country toiling buffalo a metaphor for Thailand and Southeast Asia in a globalised world—in turn aspiring and on the up, and then defeated (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Sutee Kunavichayanont, The Myth from Rice Field (Breath Donation), interactive installation, 1998. Image provided by Sutee Kunavichayanont

|

-

Siriboon revisits this familiar thematic trope and like many Southeast Asian artists deploys his body as a stage for probing the split. Sitting nude and nonchalant on a placid ox, among other young metropolitan types, male and female, standing alongside the artist naked in the field, the peroxide-haired Siriboon, with this single image, legibly marries, and so with understated irony opposes, rural-urban geographies, mores and aspirations. Eschewing literal narration, the image sets up two pseudo-realities as a critique on one side of the romanticised vision of a self-sustaining country-side imagined by nostalgic urban Thais; and on the other, the notion of a hip, open cosmopolitan Bangkok. Neither image correctly conveys the complexities and internal cleavages of the respective scenes described, yet their confrontation successfully communicates the discomfort experienced when moving between one and the other. In the current Thai climate of extreme political polarisation, it may be tempting to interpret Siriboon's imagery as a tribute to rural life. Yet what comes to the fore is not a specific positioning but rather, through humour, an in-out-weaving that argues for an evolving point of view that translates contemporary reality's uncertainty. Does Siriboon's queer identity influence this back-and-forth? Perhaps, but the methodology's regional pervasiveness, deployed by queer and non-queer artists alike, identifies Siriboon as both a Southeast Asian practitioner and a queer one (Figure 14).[49]

Figure 14. Maitree Siriboon, Dreams of Beyond, C-print, 2010. Provided by and used with the permission of Maitree Siriboon

|

Expressions of adapted self

-

Through his breakthrough practice of the 1990s, Truong Tan expressed queer sexuality. Yet as argued above, this expression must be viewed in the context of 1990s Hanoi where selected artists began to critically deal with the preserves of power. However rooted in self, once out in the world engaging audiences, especially via performance, Truong Tan's images and actions were transformative and reached beyond any specifics of queer. Here it is worth noting that his work in Hanoi is substantially different to the video he created as part of a larger installation for the influential exhibition Gap Viet Nam (1999) at the House of World Cultures in Berlin. This was a candid video depicting the artist engaging in sex with a lover. Though ultimately censored by the German organisers, it would not have passed in Vietnam. With these two distinct artistic tacks, Truong Tan reveals himself as developing his art in response to context. As a boundary-pusher, he was ostensibly tackling different boundaries, sexual tolerance in Berlin and in Hanoi the larger social order. However, the artist remains vague regarding the precise purpose of his initiatives. Paintings exhibited in Salon Natasha in 1993 and 1994, with their revolutionary homoerotic imagery, were not censored and they were ignored by the local media. This suggests the early success of the artist's camouflaged critique.[50] Though the artist suffered the closure of his 1995 Hanoi Red River Gallery exhibition, it is only more recently that Truong Tan's artistic voice has been further recognised as politically contentious in relation to the over-sized diaper installation Hidden Beauty (2007) that denounced police/administrative corruption and was exhibited at Viet Art Centre in Hanoi.[51]

-

Truong Tan's oeuvre has latterly abstained from a direct ambush of institutions and is shifting away from queer totems. In some works he gravitates to images of powerful women such as The Dancer (2005), The Wedding Dress (2001) and Mother of Peace (2009) (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Truong Tan, The Dancer, installation, 2005. Photographed by Iola Lenzi, 2008

|

-

One may conclude that Truong Tan's homoerotic art of the 1990s, expanding from the self, enlists queer sexuality as a means of questioning current realities relevant to the collective. Contextually shaped, the social challenge of these works is encrypted in their sexual iconography with the artist committed to a criticality that recalls Michael Warner's expanded understanding of queer. Confirming this broad reading of his art, in a recent public talk the artist qualified himself as a gay man who makes art rather than an artist making gay art.[52] Truong Tan's production of the 1990s, with its candid queer iconographies, reaches beyond identity politics and is in dialogue with the practices of other queer Southeast Asian artists who infiltrate public spaces in order to engage audiences in myriad and complex ways.

Conclusion

-

My examination of the production of openly queer Thai and Vietnamese artists born from the sixties to the eighties and hailing from different backgrounds uncovers an outward-turned gaze. Though representing but a small sample in a large field, this oeuvre that tackles diverse ideas, fixes centrally on society and power.[53] Truong Tan, who engages directly and graphically with queer sexuality, and Michael Shaowanasai with his often provocatively camp vision, propel viewers onto a ground where the empowerment of the individual and universal principals of freedom are at play. Practices are singular and tinged with traits born out of each artist's life experience—a queer identity fundamental to all. But this queer identity permeates the art of each in subtle ways, often obliquely.

-

The artists I have discussed in this paper, each looking beyond the self in ways characteristic of a strand of Southeast Asian contemporary art focused on social critique, are working for an inclusiveness that may resemble that advocated by the expanded queer discourse that has come to the fore in Euramerica. Contextualising their practices within an emerging Southeast Asian history of art, one detects many of regional art's defining traits. Indeed, the artists I have surveyed in this paper clearly adopt multiple view-points, are concerned with outsiders and marginal status, take advantage of conceptual approaches even as they exploit aesthetic languages, engage with local and cross-regional histories—especially forgotten or deliberately erased ones—and at times devise strategies to provoke audience participation as a means of activating social change. Like so many in the region, they sometimes use their bodies as canvasses in a way typical of so many works of Southeast Asian art that are deliberately conceived to provoke physical audience involvement.

-

Since the advent of feminist advocacy and the fight for LGBTQ identity in Euramerica—and especially in the early days of the 1970s—practitioners opted to locate themselves in these sub-groups, defining themselves and their art as opposed to or outside the larger artist collective by virtue of their gender or sexual orientation.[54] In Southeast Asia, however, though women and queer artists assert their identity in terms of 'contemporary art' they have often been preoccupied with broader human rights and liberty as they join with others to counter the conservative or officially-sanctioned mainstream views and fight for empowerment. Gender issues are not of secondary importance in the region, quite the contrary, and as has been discussed, are an entry point for much more creative artistic action. But with a variety of concerns and artistic languages as the rule, gender divides in artistic practice are attenuated in favour of a wide palette of individual, social and political interests in dialogue with the region's swiftly-evolving socio-political parameters.

-

The way gender, sexual orientation, and erotic references influence and feature in contemporary art in Southeast Asia has, as we have seen, both historic and contemporary sources: the status of pre-modern Southeast Asian women was high while in the contemporary context an active art of lobbying for empowerment is a canonical strand, any fragmentation regarding gender and sexuality subsumed by a more general struggle for human rights and personal emancipation. In Southeast Asia, principles of equality among men have not evolved over centuries as they have in Euramerica where queer rights are also now defended. In Southeast Asia, queer artists, along with many other minorities or those wary of a conformist mainstream, rather than retreating into differentiation, like their non-queer counterparts, take their practice beyond ideas of the self to produce an art of questioning not only relevant to the region but also beyond.

Acknowledgement

I wish to thank Brian Curtin for his valuable suggestions on earlier versions of this paper.

Notes

[1] In the 1990s the term Southeast Asian art was used by institutions such as Singapore Art Museum to designate works from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and in some cases Vietnam. More recently Burmese and Cambodian contemporary art have been included. Early exhibitions include Japan Foundation initiatives of the 1990s such as Glimpses into the Future – Art in Southeast Asia 1997 (1997), and Asian Modernism Diverse Development in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand (1995). Focusing also on art of the region were early Asia Pacific Triennials of contemporary art at Queensland Art Gallery; Fukuoka Asian Triennale, from 1999 and before that The Asian Art Show; Contemporary Art in Asia Traditions/Tensions (1996) at Asia Society, New York which comprised Southeast Asian, Korean and Indian art; Negotiating Home History and Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991–2011, Singapore Art Museum; Concept Context Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia at BACC Bangkok; a recent anthology of writing on the topic is Nora Taylor and Boreth Ly (eds), Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art an Anthology, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012.

[2] Caroline Turner (ed.), Art and Social Change Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, Canberra: Pandanus Books, ANU, 2005 develops this topic across Asia and Southeast Asia. Also Iola Lenzi, 'Art as voice: Political art in Southeast Asia at the turn of the twenty-first century,' in Perspectives, Asia Art Archive, online: http://www.aaa.org.hk/Diaaalogue/Details/1057 (accessed 5 August 2011).

[3] For Vietnam, see Iola Lenzi, 'Venus in Vietnam: Woman and the erotic in the art of Vu Dan Tan and Nguyen Nghia Cuong,' in Venus in Vietnam, exhibition catalogue, Hanoi: Goethe Institut, 2012; and Iola Lenzi, 'Urbane subversion: Empowerment, defiance and sexuality in the art of Vu Dan Tan,' in 12 Contemporary Artists of Vietnam, ed. Trang Dao Mai, Hanoi: The Gioi Publishers, 2010, pp. 22–24. For the region, Iola Lenzi, 'Negotiating home, history and nation,' in Negotiating Home, History and Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991–2011, ed. Iola Lenzi, Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2011, pp. 24–25.

[4] Benedict Anderson, The Specter of Comparisons, London: Verso, 1998, p. 112.

[5] Anderson, The Specter of Comparisons, p. 111.

[6] Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450–1680, vol. I, Chiangmai: Silkworm Books, 1988, p. 88 on homosexuality in Burma and p. 75 on beauty and the body.

[7] On transgender transformation, see Peter Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 412.

[8] Peter Jackson, 'Thai Buddhist accounts of male homosexuality and AIDS in the 1980s,' in The Australian Journal of Anthropology vol. 6, no. 3 (1995): 140–53, online: http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-EPT/anth.htm (accessed 15 May 2015).

[9] Sodomy charges against Malaysian opposition politician Anwar Ibrahim were first brought in 1998 and are still ongoing though ostensibly politically motivated. See John L. Esposito and John O. Voll, 'The questionable trial of Anwar Ibrahim,' ALJAZEERA, 4 November 2014, online: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/11/questionable-trial-anwar-ibrahi-201411455121912547.html (accessed 20 December 2014).

[10] See video stills of the 1993 performance, and documents relating to its outcome in the 'Ray Langenbach Archive of Performance Art,' Asia Art Archive Collection, online, http://www.aaa.org.hk/Collection/CollectionOnline/Details/33937 (accessed 15 May 2015).

[11] Yvonne Doderer, 'LGBTQ in the City, Queering Urban Space,' International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2011, pp. 431–36, p. 432.

[12] See John Boswell, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe, New York: Vintage, 1995; For a discussion of the different methodological concerns of queer interest and LGBT identities, see Brian Curtin, 'Art history,' in The Reader's Guide to Lesbian and Gay Studies, ed. Timothy F. Murphy, New York: Routledge Dearborn Publishers, 2000, pp. 57–58; and, for extensive discussion of the wide potential of ideas of queer, see Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter, New York and London: Routledge, 1993.

[13] Catherine Lord, 'Inside the body politic: 1980-present', in Art & Queer Culture, ed. Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, London: Phaidon, 2013, pp. 29–45, p. 30.

[14] Whitney Davis, 'Founding the closet: Sexuality and the creation of art history', in Art & Queer Culture, ed. Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, London: Phaidon, 2013, pp. 342–47, pp. 344–45.

[15] Michael Warner, The Trouble with Normal, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

[16] Davis, 'Founding the closet,' p. 345.

[17] Wayne R. Dynes and Stephen Donaldson, 'Introduction,' in History of Homosexuality in Europe and America, ed. Wayne R. Daynes and Stephen Donaldsen, New York: Garland Publishing, 1992, pp. vii–xix, p. xii; and Mona Chalabi, 'State-sponsored homophobia: mapping gay rights internationally,' The Guardian, 12 December 2013, online: http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/oct/15/state-sponsored-homophobia-gay-rights (accessed 15 November 2014).

[18] According to Amnesty International serious violations of fundamental human rights are a daily reality throughout the region. See 'Asia and the Pacific Human Rights,' Amnesty International: Asia and the Pacific, n.d., online: http://www.amnestyusa.org/our-work/countries/asia-and-the-pacific (accessed 15 May 2015).

[19] All argued by the author and supported by many illustrative examples, as traits of regional art over several generations in Negotiating Home, History and Nation, Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2011, pp. 7–28.

[20] See especially Turner's Art and Social Change; also catalogue writings documenting certain exhibitions: Japan Foundation's Glimpses into the Future, and Asian Modernism Diverse Development in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand (1995); early Asia Pacific Triennials of Contemporary Art at Queensland Art Gallery, APT1 (1993) and APT2 (1996); the Asia Society, New York exhibition Contemporary Art in Asia Traditions/Tensions (1996); more recently the Singapore Art Museum survey Negotiating Home History and Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991–201 (2011) and Bangkok Art and Culture Centre's Concept Context Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia (2013) the last two co-curated by the author.

[21] Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, pp. 146–47, pp. 160–61 and p. 153 on female independence in pre-modern Southeast Asia. Reid highlights women's autonomy in commercial, sexual, inheritance and divorce matters, distinct from the situation in China and India. See also Barbara Watson Andaya, The Flaming Womb – Repositioning Women in Early Modern Southeast Asia, Chiangmai: Silkworm Books, 2008, pp. 16–17 on links between rice cultivation and the mitigation of gender hierarchies in pre-modern Southeast Asia; pp. 111–12 on daughters as valued resource in Southeast Asia; pp. 110–11 on matrilineal inheritance in pre-modern Southeast Asia and female land-holders in Vietnam.

[22] Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, pp. 149–51 for distinctions between court and non-court practices. For contemporary regional art Iola Lenzi, 'NO HARD LINES gender politics in contemporary Southeast Asian art: Does a women's vernacular exist?' in Temporary Insanity – Pinaree Sanpitak, ed. Jane Puranananda, exhibition catalogue, Bangkok: The Art Center at the Jim Thompson House, 2004, pp. 21–31 on gender-neutrality in media and themes in Southeast Asian contemporary art; Lenzi, Venus in Vietnam, pp. 22–28; Lenzi, Urbane Subversion, pp. 26–28. Also Iola Lenzi, 'Politics and history in recent Southeast Asian contemporary art,' in Asian Art Newspaper, November 2010, p. 16 on artist Jimmy Ong's gender subversion of Lee Kuan Yew for political commentary in the Singapore context.

[23] Iola Lenzi, 'Breast idiom,' in breast and beyond by pinaree sanpitak – noon-nom, exhibition catalogue, Bangkok: Bangkok University Art Gallery, 2002, unpaginated, on noon nom.

[24] Iola Lenzi, 'Context, content, and meaning: Threads of perception beyond the veil,' in Stitching the Wound: Arahmaiani in Bangkok, ed. Iola Lenzi, exhibition catalogue, Bangkok: The Art Center at the Jim Thompson House, 2006, p. 23.

[25] Bui Nhu Huong, Pham Trung, Vietnamese Contemporary Art 1990–2010, Hanoi: Knowledge Publishing House, 2012, p. 17 for Mother and Son, in this publication the work is titled The Past and the Future; also see Lenzi, Venus in Vietnam, pp. 22–28.

[26] Defending this see Lenzi, 'NO HARD LINES,' pp. 22–31.

[27] The Vietnamese government has endorsed gay rights in recent years, Bruno Philip, 'Printemps gay au Vietnam,' Le Monde, 3 May 2013, online: http://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2013/05/03/printemps-gay-au-vietnam_3170455_3210.html?xtmc=gay_pride_vietnam&xtcr=1 (accessed 20 August 2014).

[28] On early works by Truong Tan, see Jeffrey Hantover, 'A singular voice,' in Asian Art New, vol. 4, no. 5 (1994): 68–69. Hantover reports the artist living in Saigon, not Hanoi. Also Melissa Chiu and Benjamin Genocchio, 'Out now the art of Truong Tan,' Art AsiaPacific no. 14 (1997): 50–53 on sexual repression as political control in mid-nineties Vietnam, and on censorship of Truong Tan's 1995 Red River Gallery show. Ashley Carruthers, 'What bugs the state about Truong Tan?,' TASSA Review vol. 7, no. 3 (1998): 4–5; Iola Lenzi, Hanoi Paris Hanoi,' ART AsiaPacific no. 35 (2002): 64–68.

[29] See part of the series Here Very Dark in Negotiating Home History and Nation, ed. Lenzi, pp. 195–96 for plates and pp. 243–44 for translation of the Vietnamese text.

[30] Truong Tan at this time does not date his work. Author's interviews with the artist Hanoi, December 2010. Salon Natasha was active from 1990–2005.

[31] German artist Veronika Radulovic, Hanoi-based during the 1990s and a regular lecturer at the Hanoi University of Fine Arts (now known as the Vietnam University of Fine Arts), exposed her Vietnamese students to various types of non-Vietnamese art.

[32] The first formal group exhibition that Truong Tan joined at Salon Natasha (Hanoi?s fist independent art space, run by Natalia Kraevskaia 1990–2005) was the 1994 Red and Yellow about artists' use of symbolic colours to explore religion, sexuality and politics. See 'Red and Yellow at the salon,' Asia Art Archive, online:

http://www.aaa.org.hk/Collection/CollectionOnline/SpecialCollectionItem/5635 (accessed 24 August 2015).

[33] Bui Nhu Huong and Pham Trung, Vietnamese Contemporary Art 1990–2010, Hanoi: Knowledge Publishing House, 2012, pp. 16–19.

[34] on Nguyen Minh Thanh's breakthroughs in the expression of the intimate and love, as well as his indirect cultural critique via the woman/mother as anchor of the family, see Natalia Kraevskaia, From Nostalgia toward Exploration: Essays on Contemporary Art in Vietnam, Hanoi: Kim Dong Publishing, 2005, pp. 60–66.

[35] In Negotiating Home History and Nation, p. 243 for translation of the Vietnamese text by Truong Tan's student Nguyen Van Cuong, January 2011.

[36] Lenzi, Venus in Vietnam, p. 27.

[37] Author interviews with Bui Cong Khanh in Saigon, March 2009; France, July 2010; Singapore, May 2014.

[38] Author interview with Bui Cong Khanh, Singapore, May 2014.

[39] Dinh Q. Le returned to Vietnam in the middle 1990s. At that time he travelled to Cambodia and in Phnom Penh visited the genocide museum that had recently been set up on the site of the infamous Tuol Sleng torture centre where in the 1970s the Khmer Rouge had incarcerated, tortured and murdered their victims. Further to this visit, the artist produced The Quality of Mercy.

[40] Author interview with Dinh Q. Le, Saigon, January 2014.

[41] See Iola Lenzi, 'Subjective truth, or art for dangerous times,' in Subjective Truth: Contemporary Art From Thailand, exhibition catalogue, Hong Kong: 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, 2013, pp. 3–4.

[42] Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art and Society, London: Thames & Hudson, third edition, 2002, p. 362 on feminist artists' choice of fabric, thread and glitter for their associations with women's cultural traditions; and pp. 363–65 on the feminist challenge to the high/low art dichotomy, versus the Southeast Asian context where artists of both sexes produce art that defies or ignores these divisions from western discourse.

[43] On meanings derived from medium in Southeast Asian contemporary art see Kitazawa Noriaki, 'Memory of hand – The potential of craft,' in Fukuoka Triennale, 2002, exhibition catalogue, Fukuoka: Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, essay 4, p. 146 on craft's differing status in Japan and the West and craft's 'concern for the other' in the Japanese context; in the same catalogue, also see Ushiroshoji Masahiro, 'Hands and collaboration – Asian art at the start of the twenty-first century,' p. 140 on the integration of craft and art; also Jim Supangkat, 'Multiculturalism/modernism,' in Traditions/Tensions: Contemporary Art in Asia, New York: The Asia Society, 1996, pp. 80–81 on the use of indigenous material and craft in Southeast Asian contemporary practice; also Lenzi, 'Home, history and nation,' pp. 18–20 for a synthesis across Southeast Asia.

[44] Iola Lenzi, 'Rape and pillage: New directions in the art of Jakkai Siributr,' in Jakkai Siributr Plunder, exhibition catalogue, Singapore: Yavuz Fine Art (YFA), 2013, pp. 3–9 and Iola Lenzi, 'Transient shelter: Jakkai Siributr's art of thoughtful resistance,' exhibition brochure, New York: Tyler Rollins Fine Art, 2014, unpaginated; Iola Lenzi, 'Conceptual strategies in Southeast Asian Art: a local narrative,' in Concept Context Contestation – Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia, ed. Iola Lenzi, Bangkok: Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 2014, pp. 14–16.

[45] Iola Lenzi, 'Lost and found: Tracing pre-modern cultural heritages in Southeast Asian contemporary art,' in Connecting Art and Heritage, ed. Bui Thi Thanh Mai, Hanoi: The Gioi Publishers, 2014, pp. 127–33.

[46] Author interviews with Jakkai Siributr in France, August 2013, and email exchange June 2014.

[47] In Singapore Tang Da Wu and Zai Kuning; in Vietnam Bui Cong Khanh, Nguyen Minh Thanh, Nguyen Van Cuong, Truong Tan and Nguyen Quang Huy.

[48] Apinan Poshyananda, Modern Art in Thailand, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 218–19.

[49] See Iola Lenzi, 'The roving eye: Southeast Asian Art's Plural views on self, culture, and nation,' in The Roving Eye, ed. Iola Lenzi and Ilkay Balic, Istanbul: ARTER/Koc Foundation, 2014, pp. 30–47 devoted to this topic.

[50] Interviews March 2014, Hanoi, Natalia Kraevskaia director of Salon Natasha affirms paintings by Truong Tan shown in Salon Natasha were not censored.

[51] In interviews with the author in Hanoi March 2012, Truong Tan described the censorship of his 1995 Red River Gallery solo show in Hanoi. Also on censorship in Hanoi in the 1990s see interview of Truong Tan by Sylvia Tsai, 'Open Boundaries interview with Truong Tan,' in ArtAsiaPacific, February 26 2014, online: http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/OpenBoundariesInterviewWithTruongTan (accessed 4 January 2014).

[52] As stated by Truong Tan during a public talk he gave at Manzi Art Space in Hanoi, 20 December 2013.

[53] Examples of recent Southeast Asian queer-themed exhibitions include the 2014 Radiation: Art and Queer Ideas from Bangkok and Manila, curated by Brian Curtin and including Jakkai Siributr, Maitree Siriboon and Michael Shaowanasai, Art Center of Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, April 2013; and Michael Shaowanasai's solo exhibition, Radu Die 1 Dawn of the Evening: Entering act V, 2012, also curated by Curtin.

[54] For a contrast in perspective, see Chadwick, Women, Art and Society, pp. 363–65 on the 1970s feminist challenge to the high/low art dichotomy versus the Southeast Asian context where male artists, through their use of materials and signs challenge the divide; and Chadwick distinguishes British feminists' focus on socialist ideologies from American feminists' focus on a politics of difference pp. 355–56.

|