Rethinking Yaoi on the Regional and Global Scale

Alan Williams

-

Yaoi is a genre of storytelling featuring male-male eroticism and romance whose primary audience is girls and women. The genre began in amateur manga (comics), or dōjinshi, culture in 1970s Japan. Today, yaoi has grown into a global phenomenon that is particularly popular in East Asia where, since the late 1990s, it has garnered millions of fans. In Sinophone contexts, yaoi is called danmei (耽美), which is the Mandarin reading of what in Japanese is read as tanbi[1] or aesthetic indulgence/intoxication by beauty. In China, danmei currently takes the form of chiefly online fan fiction on nomadic websites whose creators outwit regulators' abilities to censor them.[2] Yanrui Xu and Ling Yang trace the origin of mainland danmei to the year 1998, its continued growth drawing heavily on bootleg Japanese yaoi.[3] Danmei in Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as yaoi in Japan, South Korea and beyond have, since the 1990s, expanded from comics into films, novels, online serials and a swath of other media forms and commodities. In this essay, I will stick with the terms yaoi and danmei rather than use the more universal and commercial term 'boys' love' or 'BL'[4] so as to maintain an historical throughline between the 1970s and 80s Japanese dōjinshi predecessors and the post-1990s glocal media.

-

Yaoi/danmei takes the form of usually unintentional feminist-queer social critique, but always includes intentional titillating entertainment. In today's context of national cultures competing for soft power—what Koichi Iwabuchi has called 'brand nationalism': for example, 'cool Japan,' Hallyu (the Korean wave)—the genre performs a particular kind of affective work: that of queer stylisation. Through the creation and consumption of media featuring speculative male-male kinship, fans re-imagine in unique ways hegemonic gender roles in the realms of sex, marriage, family, career and public life. When the media is read across borders, fans engage in explicit or implicit comparisons of restrictive heteropatriarchies. Such comparisons result from a characteristic of twenty-first century modernity: a global bellwether of 'equality' by way of civil rights and/or other measures for women and sexual minorities.[5] Yaoi/danmei is a lucrative technology that alleviates 'trapped' feelings spurred by heteropatriarchy via moe, a kind of animalistic affect. The extent to which yaoi/danmei, however, draws from and contributes to brand nationalism, thereby fuelling a kind of chronopolitics, is a central concern of this essay. Scholars must contend with the probability that feminist-queer commodities play a part in the uneven power dynamics of multinational capital and its representational effects. As Iwabuchi explains, brand nationalism is a problem because nation-states are 'strengthen[ing] their alliances with multinational corporations to enhance national interests,' which results in a continued '(re)production of cultural asymmetry' in the global marketplace.[6]

-

Yaoi/danmei distribution in East Asia follows the pattern that Chua Beng Huat has observed in his formulation of a post-1990s 'East Asian popular culture sphere':[7] an 'uneven flow of Japanese and Korean … products into [Chinese contexts] with relatively little reciprocity of imports of Chinese languages products into the former two countries.'[8] This asymmetry is greatly a result of post-1970s Japanese and post-1990s Korean transnationalism. Of course, one cannot blame Japan for the lack of Chinese feminist-queer exports given the reality of mainland censorship. Yet, rather than fall prey to the teleological notion that China must therefore be 'trapped in the past,' one should think carefully about the relationship of feminist-queer commodities to capital and the 'modern' nation-state today.

-

For this, Jasbir Puar's notion of 'homonationalism' is useful. The word generally refers to the now-strong link between LGBT politics and the US state particularly. US power, even if waning, still tethers most societies to a global economy. Puar succinctly captures the intersection of multinational capital, teleological thinking (for example, the global bellwether of equality), and queer-feminist commodification when she writes: 'Freedom from gender and sexual norms' intersects nicely with the 'self-possessed speaking subject, untethered by hegemony … enabled by the stylization offerings of capitalism, rationally choosing modern individualism over the ensnaring bonds of family.'[9] What this quote demonstrates is that nation-states do not need to necessarily adopt the logic of rights to prove their modern status, so much as provide social and commercial space for queer and feminist stylisation. This dynamic best describes Japan, a country where, say, marriage rights for sexual minorities is barely on the public's radar and whose gender equality tends to be ranked abysmally, but for whom feminist-queer commodities are highly exported.[10] One result of these exports is a conflation of the nation's mediascape with its ideoscape among overseas consumers.

-

For instance, Tricia Fermin observes how in industrialising Philippines, the consumption of yaoi from Japan is not free of a perception of Japan as more modern.[11] A presumption emerges that if feminist-queer media like yaoi is so widely available and exported, then Japan itself must also be so queer-friendly and antisexist. Fran Martin, in her study of the Taiwanese danmei community, also observes a kind of teleological thinking, describing her informants as constructing an 'imagined geography' based on Japan's speculative manga worlds against which a real-life Taiwan is compared.[12] Importantly then, Japan's real-world sex/gender scene need not be held in utopian esteem for the country's modern status to be signified; only that yaoi-speculation—a kind of feminist-queer radicalism—be sourced there.

-

In mainland China, many fans uphold Mori Mari (1903–1987), daughter of the famed Japanese novelist Mori Ōgai, as the 'mother' of danmei, despite the fact that almost all of Mori's work (especially those with same-sex themes) remains untranslated into Chinese.[13] Mori has been deemed the progenitor of yaoi among Japanese scholars; her 1961 novella Koibitotachi no mori (A Lovers' Forest) is often considered the first yaoi.[14] Although Mori's pedestal as 'mother' transcends national boundaries in the name of queer love at a time when Japanese/Chinese relations are increasingly tense, and thus does a kind of critical transnational feminist work, at the same time, the origin story does curious chronopolitical work for the Japanese nation-state—even while mainland danmei fans turn to Chinese history for their storytelling purposes.

-

Since danmei risks censorship on the mainland, brand nationalism might seem less applicable a term; still, mainland danmei fans deploy intra-nationalist approaches that intersect with the global bellwether. For example, according to Xiqing Zheng, fans sometimes maintain a sense of elitism as they traffic in feminist and queer critique. Zheng alerted me to a motto among fans in the early 2000s, taken from a famous online forum called Lucifer: 同人女有义务比别人更有文化 (A fangirl has the responsibility to be more civilised/cultured than others).[15] As Lisa Rofel has explored, the spread of Chinese feminist-queer identities and storytelling in recent decades stems in large part from an impression that the ability to express one's desires and personal affairs is part and parcel of post-socialist modernisation,[16] or bringing China 'into the future.' John Wei writes of a triangulation among Japan, China and the West: the 'deep-rooted traditional preference for youthful male delicacy [in China is] intermingled with the kawaii [cute] aesthetics borrowed from modern Japanese manga and anime,' but also the 'imagined universe full of superhero masculinity, advanced technology, and science fiction spectacle … a signature of (post)industrial American modernity,' which some mainland fans prefer. These fans 'break away from the Japanese cuteness … to pursue modernization in its original Western form rather than through the medium of a Westernized and modernized Japan.'[17]

-

A contrasting and negative impression for yaoi emerges where one might expect. Jessica Bauwens-Sugimoto explores superficial readings by some US fans of 'slash'[18] fiction who claim that Japanese yaoi is 'more misogynist, more homophobic, and occasionally more racist'—in essence, inferior—to US feminist-queer storytelling due to Japan's 'greater sexual oppressiveness.' For these readers, the hybridisation of yaoi with US same-sex fictions amounts to a kind of 'pollution.'[19] Like homonationalism itself, all the above readings find roots in older forms of power: the Philippines is 'behind' Japan, Taiwan and China 'arrive' via Japan and the West, and, as seen from the US, Japan is still not 'there' yet. In Puar's formulation of homonationalism as a white logic, and indeed in Edward Said's formulation of Orientalism, Japan emerges as a kind of 'terrorist other' to a global sexual order: its mediascape polluted by both heteropatriarchy and perverse excess ('too queer' = 'not queer enough'), to include even alleged paedophilia (lolicon and shotacon).[20] Mark McLelland has written on the Japanese response to international pressure to curb perceived excess; he focuses on the 2010 Tokyo debate on whether or not to ban the depiction of non-existent youth in sexual situations, a common topos in yaoi.[21] Such content, assuredly harmless, is already illegal in a number of western countries.

-

Taking the above framework that concerns an emergent conjoining of brand nationalism with homonationalism in East Asia, for the rest of this essay I will explore globalising yaoi/danmei in three directions. First, I will focus on the genre's 'origin,' then its feminism, and then its moe, or affect. Finally, I will conclude with a short case study on the 2004 Taiwanese film Formula 17.[22]

Theorising yaoi's origin

-

In her study of the Japanese manga industry, Sharon Kinsella observed that male-male fictions for girls and women emerged nearly simultaneously in industrialised societies in the 1970s. Kinsella names Japan, the US and Britain principally, and suggests that this co-emergence points to how 'these women have undergone similar social and sexual experiences.'[23] One shared experience is a 1970s change in print technologies that enabled individual writers and artists to share their work outside local heteropatriarchal gazes (not unlike how print technologies in general enabled nation-states to form imagined communities). A noteworthy venue for this sharing is the copyright-free space Comiket, the binannual dōjinshi convention held in Tokyo since 1975 that today draws half-a-million people. In today's digital age, print-on-demand technologies and online serialisation have opened up increased venues for profit and community-building, circumventing barriers in places where yaoi/danmei either breaks the law or is heavily regulated (for example, China, Singapore, Indonesia).

-

The near simultaneous emergence of yaoi-like texts on three continents begs the question of the complicated relationship between globalisation and queer cultural formations. Peter Jackson has usefully re-raised the significance of industrialisation and modernisation vis-à-vis global queering, because of the fact that 'Japan and Siam [now Thailand] both remained independent throughout the colonial era, [and] significantly, it is in these two countries, which escaped direct colonization and self-modernized, that Asia's first modern homosexual communities emerged.'[24] Jackson suggests that discussions regarding global queering be 'pushed back' to before the post-Cold war era and the rise of the internet, even before 1970s multinational capital, because the question is not 'how Asian societies … borrowed 'preexisting' Western queer cultural patterns' but rather 'why sexual cultures in parts of Asia and the West both underwent dramatic transformations in similar, but also distinctive, ways over much the same period of the twentieth century.'[25] Japan's colonial enterprise and postwar invitation to the Cold War-era table for industrialised democracies (exclusive to Japan, the US, and Western Europe) often relegates the nation in scholarly discourse to a status of 'more or less part of the West,' although in truth, twentieth-century Japan was like the West, but not of it.[26] Conversely, China, as David Eng puts it following Rofel, gives rise to 'discrepant modernities' born from the mainland's 'nineteenth-century exclusion from Euro-American modernity and Mao's twentieth-century communist victory.'[27] ('Discrepant' does not mean 'alternative,' as the latter would amount to, as Howard Chiang suggests, 'self-/Orientalism' or an over-localization of Chinese gender and sexual discourse, and a forgetting of the near-global reach by the 1920s of what Michel Foucault called scientia sexualis.[28]) I include this meta-level conversation in Asian queer studies because it informs my understanding of yaoi/danmei, including the likelihood that yaoi and danmei are subtly different phenomena, as opposed to danmei as a mere 'copy' of yaoi.

-

For a necessary transepochal approach in thinking through yaoi's emergence, Keith Vincent's theorisation of 'two-timing' queer Japanese narratives of the first half of the twentieth-century is a useful point of departure. Vincent analyses Sōseki Natsume's 1914 novel Kokoro as a striking example of not only a forward-looking temporality for Japanese heteropatriarchy, but also a backward-looking, perverse and nostalgic temporality for the 'premodern'—that is, the Tokugawa era (1603–1868) when Japan was relatively isolated, before the empire and the global spread of scientia sexualis that pathologised same-sex sexual relations.[29] Vincent contends that as the twentieth century progressed, Japanese queer narratives became 'stuck' in a space between sexologised homosexuality (hentai seiyoku, or perversion) and invisibility whereby same-sex sexual relations (for example, nanshoku, shudō) were deemed a premodern remnant to be discarded. Vincent shows how Mishima Yukio's 1949 novel Confessions of a Mask exemplifies this mid-twentieth-century dialectical space.[30]

-

For yaoi, situated in the second half of the twentieth century, I veer from Vincent in a deployment of the 'postmodern,' revisiting the term as it was taken up in Japan in the 1980s. Azuma Hiroki reminds of how in the 1980s, at the height of the Japanese economy, great popular and scholarly interest arose toward the concept of postmodernity, which was seen as important to conceptualising that particular moment of Nihonjinron, or Japaneseness. Alongside claims that Japan had finally 'overcome modernity' or severed its reliance on comparing itself to the West (via, notably, a frontrunner status in the computerisation of knowledge[31]), the Japanese media sometimes portrayed the isolationist Tokugawa period as 'already postmodern.' That is to say, Japan was 'postmodern before it was modern.' As Azuma writes, this notion served the interests of nationalism, to 'forget [the] defeat [of WWII] and remain oblivious to the [continued] impact of Americanization.'[32] To be clear, postmodernity did little to end the violence of modernity, either in Japan or elsewhere; still, within this 1980s economic and social context, a genre like yaoi could establish a commercial foothold after a 1970s birth in underground dōjinshi markets, because heteropatriarchy had become a 'modern' remnant to be shed. Yaoi's feminist-queer narratives gained popularity as they proliferated against the grain of an ever-disappearing norm, and at the centre of the narratives were bishōnen or gender-bending 'beautiful boys.' As Greg Pflugfelder writes, 'fixing our gaze on the bishōnen' is in effect assuming the characteristic stance of Tokugawa discourse on male-male sexuality;[33] however, to follow Marilyn Ivy, the bishōnen is likely phantasmatic.[34]

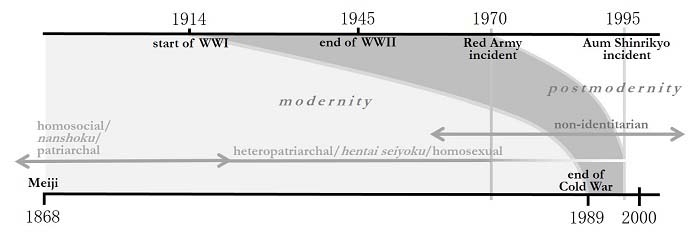

Figure 1. Merged timelines from Hiroki Azuma illustrate the global transition from 'modernity' to 'postmodernity.' The light grey curve indicates the transition by the end of the Cold War (communism-vs.-capitalism as the last 'grand narrative'); the dark grey curve indicates the fall of Japanese grand narratives particularly. Azuma, following the work of sociologist Ōsawa Masachi, divides postwar Japanese narratives into three eras: the Era of Ideals (1945–70), the Era of Fiction (1970–1995), and—Azuma's addition: the Era of Animals (2000–onward). Given that heteropatriarchy qualifies as a 'grand narrative,' I have overlaid Keith Vincent's 2012 theorisation of two-timing 'pre/modern' queer Japanese narratives (the lower arrowed line). My addition for yaoi-like texts is also two-timing, but 'post/modern' (the upper arrowed line).

Source: Azuma Hiroki, 'The animalization of Otaku culture,' trans. Yuriko Furuhata and Marc Steinberg, Mechademia vol. 2 (2007): 175–87, p. 179.

|

As an observation of yaoi's 'post/modern' form, consider how a common utterance in the genre—when a character claims that he is 'not gay, but just in love with a man'—has both homophobic (or modern) temporal undertones but also non-identitarian (postmodern) ones. Consider too how yaoi fans often identify as 'straight/gay/lesbian' and so on, due to the preponderance of such labels in their societies, but also have an attraction to yaoi that crosses identitarian borders. Following Mizoguchi Akiko who identifies as both an 'out lesbian' and a 'person of yaoi sexuality,'[35] I too identify as 'gay' out of habit, but the label has a rather dated feel to it when compared to the circulation of desire in yaoi fandoms.

-

Other scholars have pushed on the boundaries of yaoi's origin. Jeffrey Angles argues that the genre appears to 'partake of a palate of aesthetics created by early twentieth-century [Japanese] writers … who saw homoerotic appreciation of boyish beauty as an intense aesthetic experience and a sign of deep, personal feelings that could define one's experience as an individual.'[36] Angles' claim is practical in part because of how it points to an earlier practice of individuation that is central to the troubling nexus of late twentieth-century feminist and queer politics, capital and the nation-state, or homonationalism. My sense is that the 1960s and 70s tanbi shōsetsu or male-male 'aetheticised novels' (yaoi's precursors) of Mori Mari and her contemporaries do not only descend from earlier writings about beautiful boyishness, per se, but to the tanbishugi or Japanese aestheticism movement altogether, of which Mori Ōgai was a participant.[37] Like the decadent literature (for example, the work of Oscar Wilde) that emerged in the fin-de-siècle West as a pessimistic response to the incursion of modern 'progress' that seemed to both endorse but also strip away individuality, tanbishugi arose in response to Japan's rapid modernisation. It was a literary space in which any number of personal indulgences could maintain merit even as modern discourse insisted they disappear.

-

Same-sex sexuality under scientia sexualis in both Japan and the West was/is maligned not only for an unnaturalness or immaturity, but also for being unnecessary for the re/productive nation-state (still significant given Japan's population woes). Same-sex sexuality was 'decadent' in that it was thought aligned with bourgeois excess—not simply a remnant of the premodern, but a consequence of the modern gone awry. Pre- and postwar Japanese Marxists were torn in their readings of tanbishugi, as some felt the texts simply lavished in individualised and self-absorbed excess (erotic, or otherwise) and did not aspire to the same anti-modern ideals that western fin-de-siècle literature did; conversely, others felt the texts provided a sensible escape from the strictures of modern life.[38] The same debate could be overlayed onto yaoi/danmei today, since the texts both work for individualist materialism that feeds into brand nationalism yet are also queer/feminist sanctuaries. Establishing a link between yaoi and tanbishugi moves a focus away from same-sex sexuality as anti-modern (the rise of homonationalism proves that it is not), instead reading yaoi's 'decadence' on a long line of historical ruptures.

-

James Welker has documented that when yaoi emerged in the 1970s, some fans, particularly queer women, consumed images of 'homo men in Japan as well as abroad.'[39] Welker's foregrounding of globalisation usefully disrupts the idea of yaoi's origin as entirely Japanese. He points to how early yaoi, such as Takemiya Keiko's 1976 Kaze to ki no uta (Song of Wind and Trees) (often deemed the first yaoi in manga form), tended to hearken to 'fantastic worlds of the European past' so as to cast off 1970s' Japanese mores.[40] Welker contends that the genre for many readers was not merely an 'escape or a straightforward critique of [local] patriarchal romance paradigms … but rather [a] part of a larger sphere of consumption of images of male homosexuality.'[41] His argument is a critique of the problematic tendency to categorically divorce female-driven fantasy from real-world male homosocial worlds, a practice Welker traces to before the 1992 yaoi ronsō (dispute, or critical debate) that concerned whether the genre was appropriating queer men.[42]

-

Rather than posit an origin, Aoyama Tomoko emphasises how the genre grants the ability to 'change elite homosexual, homosocial and misogynistic literature into a more inclusive, egalitarian narrative/fantasy' through mediums such as parody and pastiche.[43] Like Vincent, Aoyama usefully follows twentieth-century perspectives regarding Sōseki's widely-read 1914 novel, Kokoro, which are worth revisiting here. Scholarly readings in 1950s' Japan and the US deemed the central male-male relationship between Sensei and K to demonstrate the fall of Meiji-era homosociality, conceived as non-erotic.[44] Then, in 1969, the influential psychoanalyst Doi Takeo read the novel's central relationship as one of latent homosexuality, a kind of sickness in Sensei that sexology could fix;[45] later 'gay' readings put a positive spin on a homosexuality conceived as obvious in the text. Aoyama cites Stephen Dodd who writes that, because of the likely practice of same-sex relationships in elite schools during the Meiji era, the 'contemporary readers of Kokoro must have been sensitive to the homoerotic elements implicit in the text.'[46] Yet another approach is taken by Vincent in his theorisation of 'two-timing' pre/modern narration that follows the dialectical historicism of queer theorist Eve Sedgwick. What might be considered as against all of these readings, Aoyama writes of a mid-1990s anachronistic declaration of Kokoro as 'boys' love' or yaoi. I would categorise this as a 'post/modern' reading, since it demonstrates both a concern with the history of the text (the declaration was made in a pedagogical context), but also with speculative romance and eroticism for enjoyment and style—as if consuming, as Aoyama says, a different text.

Yaoi's feminism

-

If yaoi/danmei is in cahoots with 'brand homonationalism,' is the genre feminist only on the local level because fans cannot be expected to concern themselves with cultural asymmetry and multinational capital?

-

In fact, to label yaoi 'feminist' is to remind that 'discrepant modernities' (to momentarily borrow Rofel's phrase) exist within the borders of nation-states along such lines as sexual difference, language difference, racial difference, and so on—modalities that have historically brought about failures of interpellation, or non-integration into nation-state logics.[47] Such 'failure' tallies with what 1970s French feminist psychoanalytic thinkers conceptualised as 'women's writing': texts distanced from the phallocentric discourse that Julia Kristeva described as opening an ultimately anti-colonial temporality of 'women's time.'[48] In his reading of Kristeva, Homi Bhabha notes that the concept of 'women's time' is not only rooted in the cultural particularities of French psychoanalysis, but also anti-colonialism because of how the temporal borders of nation-states are shaped by the same processes of signification that shape phallocentricity.[49] Takahara Eiri suggests that the figure of the bishōnen as taken up throughout twentieth-century Japanese literature and in yaoi not only resists heteropatriarchy, but the phallocentricity of the modern subject;[50] that is to suggest, the bishōnen, phantasmatic as he may be, may yet potentially retain anti-modern qualities, even if same-sex sexuality does not. In a perhaps related theorisation, Nagaike Kazumi builds on Miyasako Chizuru by labelling yaoi 'hi-shōjo' (anti-girl or non-girl) in that the genre refuses the shōnen/shōjo (boy/girl) divide and the accompanying and often nation-building gender roles and media practices inherent in the distinction.[51]

-

That yaoi continues to do local feminist work in Japan is evident in how the Japanese phallocentric gaze pigeonholes the genre's producers and consumers as immature 'fujoshi' (rotten girls/women).[52] Fujoshi are expected to, and in many cases do, outgrow the genre upon adulthood when they take on responsibilities such as a career, spousehood and/or motherhood.[53] Meanwhile, the consumption of yaoi/danmei on a regional scale by millions of fans and its hybridisation with local feminist and queer cultures is a growing site of contradiction as 'mature' nations are expected to abandon heteropatriarchy to meet the standards of the global equality bellwether.

-

Importantly, the conception of fujoshi as 'immature' is to some extent a result of 1990s feminist framings. When yaoi first entered Japanese scholarly discourse, a number of theorists posited it as a sign of phallocentrism. As the theories went, patriarchy leads females to adopt imagined male subjectivities because patriarchy often does not allow girls to comfortably express sexuality such that some adopt Freudian penis-envy.[54] The exploration of inner desire through shōnen'ai (double-meaning: 'love of boys' and 'love between boys') was deemed safer and more freeing. The queerness of yaoi was conceived as a temporary placeholder for what would become 'normative' female sexuality in adulthood, and yaoi characters were assumed to be basically 'girls with penises.'[55] Although born from a critique of patriarchy, what this penis-envy theory buttressed is a discernment among the Japanese public that yaoi is a tolerable, even welcome public good in shōjo (girls') culture because it provides the necessary skills to move girls from 'passive' to 'active' sexuality; yet, in josei (women's) culture and among women who consume shōjo, it is a mark of immaturity and/or perversity.

Figure 2. A movement of 'maturity' in yaoi.

|

Wataru and Yuichi go from unspeakable attraction to comfortable enough with themselves that they kiss in front of Yuichi's young niece as a way of showing her that neither of them can marry her when she grows up as she had hoped.

The niece represents a young reader grappling with her self-actualisation as a sexual being, learning that the process is one of individuation. Yuichi comments to her: 'See? Us big boys are reeaally good friends, so there's no way that either of us can marry Takano (the niece's name).'

Takano tells her mother on the next page: 'You know what? The big boys, they were smooching.'

The mother has the final line of the story: 'Oh my! But … it's certainly possible …'

Source. Satoru Kannagi and Hotaru Odagiri, Only the Ring Finger Knows, Carson, CA: Digital Manga, 2004.

|

-

More recent scholarship reads to me what seems a kind of essential queerness into yaoi that respects the continued consumption of the genre in adulthood, the multitude of gender performances within the texts, and breaks down the hetero/homo binary, giving voice to fans of various genders and sexualities. As if to put an end to the penis-envy theory, Nagaike argues that yaoi fans are not viewing the characters in the sense of a Freudian subject/object dichotomy; rather, female and sometimes male desire is overlaid onto fictional male bodies, resulting in identification.[56] Nagaike employs Melanie Klein's psychoanalytic notion of 'projective identification' whereby the 'other' (as opposed to a 'boy') is enlisted in the restitution of an anxious ego.[57] Notably, projective identification might be read alongside Scott McCloud's thesis that the medium of comics invites readers to identify with the 'other' via the necessity to close the gap between panels.[58] Valérie Cools suggests that Japanese manga embrace this phenomenological quality especially, which has contributed to manga's worldwide popularity.[59]

-

Nevertheless, any 'essential queerness' cannot be left unexamined. The material cultures of 'failed' subjects (women, queers, racial 'others') have, since the 1970s and rise of multinational capital, been largely reintegrated into nation-state logics via policies of cosmopolitanism over assimilation. For instance, consider yaoi's commercialisation in Japan: interpellative failure provided an occasion for entrepreneurialism. Once the mechanism for yaoi was commercially established, girls and women could 'play sexuality'[60] and the genre became less explicitly anti-hegemonic; once exported, it has contributed to brand nationalism. Fran Martin, in her study of the Taiwanese danmei community, writes that the fandom in Taiwan today sees an uneven incorporation of feminist critique with an interlinked relationship to 'social-realist tongzhi [gay] narratives'; she concludes that a 'specific ideological stance' is perhaps less important than the 'broad social function' danmei provides for its diverse fans.[61] (Martin admits that this is a change in her thinking from an earlier conception of the fandom as a 'counterpublic'—Michael Warner's term.[62]) Mizoguchi Akiko's stance is similar for Japan: yaoi remains ideal feminist praxis because there never was such a thing as clear-cut feminist activism.[63] Indeed in China, the genre is anti-hegemonic in the sense that fans outfox the state. However, even as yaoi/danmei reveals tensions between local heteropatriarchies and stylised individualisms, scholars should not lose sight of such tensions as symptoms of 'brand homonationalism.'

Yaoi's moe

-

Azuma has written extensively on the 'postmodern' as constituting a loss of interest in grand narratives and an increased interest in stylised difference as taken up through character commodities—a rise of what he calls an 'Era of Animals.'[64] As the producer of the regionally-popular 1990s TV drama Tokyo Love Story put it in 2001, viewers want beautiful people, beautiful clothes, good food and good entertainment; a good plot is secondary.[65] Gabriella Lukács has written on how the shift from story-driven narratives to lifestyle-oriented narratives in 1990s Japanese TV dramas served to redirect youth from growing inequality during Japan's [ongoing] recessionary period.[66] A decadent aesthetics in the face of failed modern 'progress' can be observed in yaoi as early as the 1970s dōjinshi, which tended to consist of mere sexual images and permutations of bishōnen with little coherent plot, resulting in the coining of the genre: 'yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi' (no climax, no plot, no meaning).[67]

-

Character commodities provide escapist and animalistic affect called moe. Moe is a term that has spread across East Asia that describes the euphoric draw of cuteness, beauty and eros as well as other appealing elements that the Japanese cultural industry takes as defining features of its popular culture export logic. To describe moe as might Walter Benjamin, it is animalistic desire—from mothering instincts to the erotic—that provides an illusion of jetztzeit (the here-and-now) or the 'aura' blasting open the homogenous, empty time of capital; yet, the affect is structured into capital as a means of containing human difference.[68] Anne Allison has fittingly named moe-inflected capital 'Pokémon capitalism,' whereby character commodities serve 'the lifeline of human relationships … relieve stress and reflect the 'inner self'[69]; they are, in essence, 'therapy' against living in the throes of multinational capital. Yaoi's use-value is in its queer stylisation potential: a disruption of local heteropatriarchies, gender fluidity, attention to deep desire and cuteness/beauty, comforting moe.

-

On the one hand, moe enables men and boys to get in touch with their 'feminine' side since a concentration on character commodities distances males from the performance of the masculinist nation-state.[70] Moe also works against compulsive heterosexuality, to use Adrienne Rich's phrase, to the chagrin of those who have conceived Japanese consumerism to amount to the public becoming non-reproductive shōjo.[71] On the other hand, as Azuma reminds, desire was never satisfied with the physiological climax (see note 57 of this essay on Lacan); ordinarily humans build intersubjective desire to resolve this insatiability, except moe 'closes various lack-satisfaction circuits.'[72] Azuma notes of an initial impression that the Japanese yaoi fandom seems 'more human' than male otaku or popular culture fans—that is to say, fujoshi engage in more intersubjective sharing.[73] But the younger generation (and this was stated by Azuma in 2001) is 'beginning to be animalized.'[74] The above dynamic illustrates the political impasse of feminist/queer desire alongside stylised individuation: capitalism may destroy hated social hierarchies, but it also conditions the human psyche toward its own empty time (see Benjamin above).

-

Patrick Galbraith usefully reads yaoi moe under the framework of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's 'body without organs,' which is not simply a pun on the fact that yaoi often features bishōnen without phalluses.[75] Galbraith reads yaoi-speculation as a space of unstructured feminist potential, not unlike Martin's claim that a 'broad social function' is more important than a 'specific ideological stance.' Consider, too, how Vincent pits Azuma's 'animalisation' (reducing it to a theory of cultural decline) against Saitō Tamaki's view for otaku (and yaoi) sexuality as subjectively productive.[76] Each of these readings strikes me as overoptimistic when a proliferation of identities, affects and performances is central to multinational capital today. Slavoj Žižek argues that there are, in fact, two Deleuzes—the first asserts the subversive potential of pre-subjective affects and immanent desire (whom Žižek labels the 'Guattarized' Deleuze), or the Delueze who might argue for modernity's potential overcoming through 'postmodern' means.[77] The trouble Žižek finds with pre-subjective affects, of which moe would undoubtedly be included, is that while their self-organisation might seem to resist regimes of power (which is how 'affect' has been naïvely deployed in many 'radical' Anglophone conversations), the affects are, in fact, compatible with database/digital capitalism. In contrast, Žižek points to a second Deleuze, before the influence of Guattari, who foregrounds the inertness of the affects, offering instead a 'quasi-causality' that anchors the network of the material, what Žižek calls 'organs without bodies.' This latter Deleuze might assert how the violence of modernity persists notwithstanding 'postmodernity.' The application of this second option to yaoi amounts to a critical (and Nietzschean) push against a simplification of yaoi moe as 'basically good' because of its generation of 'a thousand tiny sexes,' to use Elizabeth Grosz's phrase.[78] Rather, as I have shown by reading yaoi/danmei on the scale of the regional and global, the genre is in dialectical conversation with late modern elements (for example, homonationalism, brand nationalism), inherently doing 'evil' work, too.

Formula 17: A case study

-

To conclude this essay, I will explore the 2004 Taiwanese film Formula 17 (local title: 17-Year-Old's World), directed by then-24-year-old Chen Yin-jung. On international fan lists, Formula 17 is regularly annotated as a 'yaoi,' 'danmei' or 'boys' love/BL' film. The reason I choose it is because it was the highest-grossing homegrown Taiwanese film of 2004 and travelled global film festival circuits. Its reception provides an interesting case study for thinking about regional brand homonationalism in the mid-2000s. Furthermore, since the mid-2000s, Taiwan has become the oft-cited most liberal location in Asia, drawing tens of thousands during the island's annual LGBT Pride events. Petrus Liu reminds us that Taiwan is paradoxically tolerant and intolerant: the country's tolerance was, in part, designed by the state to distinguish Taiwan from China, while the 2003 move to become the first Asian nation to legalise same-sex marriage was 'nothing more than a political ruse.'[79]

-

For additional context, note that in 2005, Taiwanese director Ang Lee released a somber same-sex love story about two cowboys in rural Wyoming: a filmic version of Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain. The commercial success of Lee's film provided an occasion for US pundits to comment on growing US tolerance of homosexuality in relation to an alleged homophobia of other countries, such as China, where the media celebrated Lee's Oscar win for best director despite Brokeback Mountain never screening in Chinese theatres (bootleg versions were readily consumed, however).[80] Meanwhile, in Taiwan, an affective opposite of Brokeback Mountain saw popularity: Formula 17, a bubbly, same-sex romantic comedy populated by male idols and their comical sidekicks flirting with same-sex sexuality. Formula 17 was a low-budget production that did not see theatrical release in China.

-

Nor did the film see release in Singapore where it was banned. To justify the ban, Singapore's regulators cited the film's 'illusion of a homosexual utopia, where everyone, including passersby, is homosexual and no ills or problems are reflected … [the film] conveys the message that homosexuality is a normal and natural progression of society.'[81] Interestingly, the following year, Singapore permitted Brokeback Mountain because the US film did not 'promote or glamorize the lifestyle.'[82] After a resubmission in 2004, the 2001 Hong Kong film Lan Yu (dir. Stanley Kwan) was given a green light by Singapore's regulators for the same reason—'not promoting the lifestyle'—despite the fact that the film has more explicit sexual content than Formula 17.[83] In essence, Brokeback Mountain and Lan Yu provide ample affective space for heteronormative kinship to remain a cherished norm, whereas Formula 17 completely sidesteps it in favour of speculative queer kinship.

-

Formula 17 features a fantasy Taipei in which everyone is not only same-sex attracted, but also male. A single child appears in a flashback, accompanied by his father—a mother is intentionally absented—leaving the matter of reproduction speculative. Although a speculative world where no females exist can seem the ultimate sign of antifeminism, the film is actually indicative of its female consumer base looking for a momentary escape from everyday gender norms and private male-male activities on tantalising display. Formula 17's plot is formulaic: boy likes boy, boy gets boy, boy loses boy, but retrieves boy in the end. In one scene, the main character's best friend Yu enters a long-distance relationship with a white, English-speaking tourist who asks Yu to learn to recite 'I love you' in multiple languages. Their relationship crumbles as if resulting from Yu's failure to be cosmopolitan enough. Yu becomes catatonically depressed, yet his misfortune is played for laughs, as the film's central romance is between T'ien and Bai who are fully localised.

-

Taipei is as much on display as T'ien and Bai, as if to express to the viewer that one need go nowhere but Taipei to find the sappiest, most perfect love one could ever dream of. As Brian Wu writes, the fact that such a utopia 'includes instantly recognizable Taipei locations such as Warner Village, Ximending, and especially Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (the ultimate symbol of conservatism in Taiwan), suggests a playful queering of Taipei.'[84] Local factors for Formula 17's commercial success included Taiwan's inchoate film industry that is more amenable to untested narratives; smart casting, cinematographic and marketing choices;[85] and Taiwan's yet-to-be-decided nation-state status that facilitates cosmopolitan populism and relatively greater flexibility in the regimes of gender and sexuality. As Wu writes, in the global marketplace, Formula 17 served as an 'international spectacle (as 'authentic' Asian queer),' providing struggling Taiwanese cinema cultural capital.[86]

Figure 3. Bai and T'ien, first kiss.

Source. Formula 17, dir. Chen Yin-jung, Taiwan, 2004.

|

-

I would further argue that the popularly of films like Formula 17 and the continued spread of yaoi/danmei is an indication of a transition concerning queer narration across broader East Asia. While regulators make it difficult to judge just how profitable queer stylisation might be, the transition is evident from relatively 'liberal' Taiwan to relatively 'conservative' South Korea. Jeeyoung Shin writes of the South Korean context, where yaoi is also gaining popularity, and where films featuring male-male romance such as The King and the Clown (2005) and No Regret (2006)[87] were unexpected smash hits.[88] She aptly remarks that a 2001 model for categorising queer East Asian films as proposed by Chris Berry is now defunct. Berry contended that because the influence of Confucianism dominates East Asia, films with queer themes that see mainstream success necessarily explore how same-sex sexuality negotiates with heteronormative kinship (family dynamics, male-female courtship, the nation), whereas less popular independent or experimental films offer narratives of usually solitary existence apart from said kinship.[89] Berry's model assumes queer sexuality to be a disruptive element, whereas increasingly popular East Asian films with queer themes, particularly films infused with yaoi/danmei sensibilities, demonstrate how great profit can lie in the feeling of non-normative sexuality as not only constructive, but as an ideal point of departure.

-

As Huat notes in his reading of the East Asian popular culture sphere, the narrative of 'neo-Confucianism' as the driving force of cross-border capital of the Asian Tigers (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, and the economic opening up of China, all following regional frontrunner Japan) dissolved following the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Today, East Asian national identities are underpinned by an accelerated temporality that, 'unlike the Confucian identity that is supposed to seep quietly, through years of implicit socialization … [are now] a conscious ideological project … based on the commercial desire of capturing a larger audience and market.'[90] Yaoi and danmei are important for imagining where this ideological project might lead as brand homonationalism takes root in the region.

Notes

[1] Tanbi was a term used in the Japanese yaoi subculture in the 1970s and 80s for works that used flowery language and uncommon kanji (requiring a high level of reader fluency). See next section for a recommended link between tanbi and the twentieth-century Japanese aestheticism or tanbishugi movement.

I would like to thank the following people for their input as I developed this paper: Carolyn Allen (and company), Andrea Arai, Toshie Honda, Chris Lowy, Mark McHarry, Clark Sorenson, Alvin Wong, and Xiqing Zheng.

[2] See Ting Lui, 'Conflicting discourses on boys' love and subcultural tactics in Mainland China and Hong Kong,' Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific no. 20 (2009), online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue20/liu.htm (accessed 1 September 2014).

[3] Yanrui Xu and Ling Yang, 'Forbidden love: incest, generational conflict, and the erotics of power in Chinese BL fiction,' Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics vol. 4, no. 1 (2013): 30–43, p. 30. Xu and Yang note that confident fans today publish printed works in Taiwan given the difficulty of publishing danmei on the mainland.

[4] A settling of the name for the genre into 'boys' love' or 'BL' as the result of 1990s commercial investment I take from Saito Kumiko, 'Desire in subtext: gender, fandom, and women's male-male homoerotic parodies in contemporary Japan,' Mechademia no. 6 (2011): 171–91, p. 172.

[5] As examples of this bellwether, consider US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's declaration before the United Nations in 2009 that 'gay rights are human rights,' or French President Nicolas Sarkozy's statement in 2011 that equality between men and women is a feature of the French national character (an indictment against Arab and other immigrants who 'refuse' to assimilate). The bellwether dictates that every society must 'catch up' to a standard set by the Euro-American industrialised world or risk the wrath of exclusionary development and immigration policies, and/or suffer a burden of feeling trapped 'in the past.' Russia's recent antigay swing might be viewed, in part, as an assertion of anti-American power; so might China's reluctance to embrace a Euro-American sexual order by way of censorship.

[6] See Iwabuchi Koichi, 'Undoing inter-national fandom in the age of brand nationalism,' Mechademia no. 5 (2010): 87–96, p. 92.

[7] See Chua Beng Huat, 'Conceptualizing an East Asian popular culture,' Inter-Asia Cultural Studies vol. 5, no. 2 (2006): 200–21.

[8] Chua Beng Huat, 'Engendering an East Asia pop culture research community,' Inter-Asia Cultural Studies vol. 11, no. 2 (2010): 202–06, p. 204.

[9] Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times, Durham: Duke University Press, 2007, pp. 22–23.

[10] Although I link homonationalism with yaoi/danmei in this essay, I should note that after a panel presentation by Helen Hok-Sze Leung and Audrey Yue, 'Queer Asia as method,' Modern Language Association, 11 January 2015, Vancouver, BC, Canada, I came under a distinct impression of an already-present need to 'provincialize homonationalism' when thinking about queerness in Asia.

[11] Tricia Fermin, 'Appropriating yaoi and boys love in the Philippines,' Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies vol. 13, no. 3 (2013), online: http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol13/iss3/fermin.html (accessed 1 September 2014).

[12] Fran Martin, 'Girls who love boys' love: Japanese homoerotic manga as trans-national Taiwan culture,' Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, vol. 13, no. 3 (2012): 365–83, p. 375.

[13] I thank Xiqing Zheng for her insights into danmei culture. Zheng's dissertation work at the University of Washington is on danmei.

[14] For an English translation of Mori's A Lovers' Forest, see Nagaike Kazumi, Fantasies of Cross-dressing: Japanese Women Write Male-male Erotica, Brill, Boston, 2012, pp. 137–85.

[15] Zheng, personal communication, e-mail, 3 February 2014.

[16] See Lisa Rofel, Desiring China: Experiments in Neoliberalism, Sexuality, and Public Culture, Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

[17] John Wei, 'Queer encounters between Iron Man and Chinese boys' love fandom,' Transformative Works and Cultures no. 17, online: http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/561/458 (accessed 1 December 2014).

[18] In the West, yaoi has regularly been compared with Anglophone 'slash,' or male-male parody fiction, that also emerged in 1970s women's culture in response to frustrations with gender normativity in popular media. For slash, see Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture, New York: Routledge, 1992, pp. 185–222. For slash and yaoi as co-emergent, see Mark McLelland, 'Why are Japanese girls' comics full of boys bonking?' Refractory: A Journal of Entertainment Media, vol. 10, no. 4 (2006), 1–14. Unlike yaoi, 'slash' cannot [yet] commercialise due to copyright law, whereas yaoi encompasses both parody and 'original'-character fictions and has, especially since the 1990s, acquired extensive investment capital and distribution. Anglophone readers have an 'M/M' or 'male-male romance' genre that features original characters; M/M was born in the 1990s and is sustained by online small presses.

[19] Jessica Bauwens-Sugimoto, 'Subverting masculinity, misogyny, and reproductive technology in SEX PISTOLS,' Image & Narrative vol. 12, no. 1 (2011): 1–18, p. 2, online: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/123 (accessed 1 September 2014).

[20] I want to thank an anonymous reviewer for this insight.

[21] See Mark McLelland, 'Thought policing or the protection of youth? Debate in Japan over the 'non-existent youth bill,' International Journal of Comic Art (IJOCA) vol. 13, no. 1 (2011): 348–67.

[22] Formula 17 (17歲的天空), Dir. Chen Yin-jung, Strand Releasing, 2004.

[23] Sharon Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society, Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2000, p. 126.

[24] Peter Jackson, 'Capitalism and global queering: national markets, parallels among sexual cultures, and multiple queer modernities,' GLQ vol. 15, no. 3 (2009): 357–95, p. 366.

[25] Jackson, 'Capitalism and global queering,' p. 365.

[26] When speaking of Japan's colonial mimicry, one can apply Homi Bhabha's phrase 'not quite/not white.' Homi Bhabha, 'Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse,' October vol. 28 (1984): 125–33, p. 132.

[27] See David Eng, 'The queer space of China: Expressive desire in Stanley Kwan's Lan Yu,' positions: east asia cultures critique vol. 18, no. 2 (2010): 459–87. The phrase 'discrepant modernities' is from Lisa Rofel's 2001 essay 'Discrepant modernities and their discontents,' positions: east asia cultures critique vol. 9, no. 3 (2001): 637–49.

[28] Howard Chiang, '(De)Provincializing China: Queer historicism and sinophone postcolonial critique,' in Queer Sinophone Cultures, ed. Howard Chiang and Ari Larissa Heinrich, London: Routledge, 2014, pp. 19–51, p. 32.

[29] Keith Vincent, Two-timing Modernity: Homosocial Narrative in Modern Japanese Fiction, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2012.

[30] Vincent, Two-timing Modernity, p. 211, makes the case that the misogyny and often-deemed internalised homophobia in the storytelling of the celebrated novelist Mishima Yukio is 'less the stubborn remnants of a traditional culture than the affective precipitates of a modern homosocial narrative frozen into immobility.' Mishima's 1949 debut novel Confessions of a Mask presents same-sex attraction initially in a manner of childhood nonchalance; the narrator, who is often assumed to resemble Mishima himself, feels troubled with his attractions only as he grows older and exhibits disdain toward women. Vincent writes, that the problem for Mishima's narrator is not that he is coming to terms with any kind of 'innate' orientation (a homo/hetero binary is lacking in the text, and misogyny is certainly not innate); rather, he is coming to terms with his 'failure to "graduate" from an earlier stage' (p. 179).

[31] See Marilyn Ivy, 'Critical texts, mass artifacts: The consumption of knowledge in postmodern Japan,' in Postmodernism and Japan, ed. Masao Miyoshi and Harry Harootunian, Durham: Duke University Press, 1989, pp. 21–46.

[32] Azuma Hiroki, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, trans. Jonathan Abel and Shion Kono, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009, p. 22.

[33] Gregory Pflugfelder, Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse 1600–1950, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1999, p. 225.

[34] Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 241, writes about the process of Japan's need for tradition as an ever-vanishing phantasm in the face of the modern: 'the very search to find authentic survivals of premodern, prewestern Japanese authenticity is inescapably a modern endeavor, essentially enfolded within the historical condition that it would seek to escape.'

[35] Mizoguchi Akiko, 'Theorizing comics/manga genre as a productive forum: yaoi and beyond,' in Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale, ed. Jaqueline Berndt, Kyoto, Japan: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University, 2010, pp. 145–70, p. 164.

[36] Jeffrey Angles, Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishōnen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, p. 245.

[37] I would like to thank Chris Lowy for opening my eyes to this link.

[38] Ikuho Amano, Decadent Literature in Twentieth-Century Japan, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 8–11.

[39] James Welker, 'Flower tribes and female desire: Complicating early female consumption of male homosexuality in shōjo manga,' Mechademia vol. 6 (2011): 210–28, p. 211.

[40] James Welker, 'Beautiful, borrowed, and bent: Boys' love as girls' love in shōjo manga,' Signs vol. 31, no. 3 (2006): 841–70, p. 857.

[41] Welker, 'Flower tribes and female desire,' p. 223.

[42] Welker, 'Flower tribes and female desire,' pp. 223–24 n. 1. In 1992 Japan, concern over appropriation played out during a dispute/debate published in the women's journal Choisir in which a queer man named Satō Masaki claimed that yaoi fans were profitting from and reducing queer males into unrealistic, masturbatory fantasy. Considerable response to Masaki followed, taking various forms, such as 'yaoi was never meant for gays,' 'yaoi is liberating for women,' 'yaoi is indeed pornography,' and 'manga that targets gays isn't realistic either.' Masaki compared yaoi fans to 'dirty old men' who watch lesbian pornography, and described the genre as 'creating and having a skewed image of gay men as beautiful and handsome, and regarding gay men who do not fit that image and tend to "hide in the dark" as garbage.' (See Wim Lunsung, 'Yaoi Ronsō: Discussing depictions of male homosexuality in Japanese girl's comics, gay comics and gay pornography,' Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context no. 12 (2006), paragraph 14, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue12/lunsing.html (accessed 20 March 2015). For more discussion and analysis of the yaoi ronsō, see Keith Vincent, 'A Japanese Electra and her queer progeny,' Mechademia no. 2 (2007): 69–76; Mizoguchi Akiko, 'Reading and Living Yaoi: Male-Male Fantasy Narratives as Women's Sexual Subculture in Japan,' Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester, 2008, pp. 179–89; and Mark John Isola, 'Yaoi and slash fiction: Women writing, reading, and getting off?' in Boys' Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre, ed. Antonia Levy, Mark HcHarry and Dru Pagliassotti, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011, pp. 84–98, pp. 86–91.

A similar concern of appropriation manifested as what might be deemed an 'M/M romance dispute' in the US in 2009 and 2010. The Lambda Literary Foundation limited its awards to those who identify as LGBT, a move perceived by many as a response to the influx of heterosexual women on the scene writing high-quality male same-sex romance (see 'Lambda Literary Foundation announces new guidelines for Lambda Literary Awards submissions,' Lambda Literary Foundation blog, 29 August 2011, online: http://www.lambdaliterary.org/reviews/08/29/lambda-literary-foundation-announces-new-guidelines-for-lambda-literary-awards-submissions/ (accessed 1 September 2014). That enforcement of the rule was short-lived speaks to how apprehension about appropriation has fallen away in recent years as a result of increased integration of homosexuality into US state and mainstream media logics (e.g., marriage rights, etc), or homonationalism. As what could be read as a kind of conclusion to the yaoi ronsō in Japan, Mizoguchi Akiko, 'Theorizing comics/manga genre as a productive forum: yaoi and beyond,' states that yaoi is now 'a few steps ahead of reality in contemporary Japanese society in the direction of equal rights for homosexual individuals' (p. 161); yet, for a country in which legislation for sexual minorities is barely a public issue, what such rights might entail is yet to be seen.

[43] Aoyama Tomoko, 'BL (Boys' Love) literacy: subversion, resuscitation, and transformation of the (father's) text,' U.S.-Japan Women's Journal vol. 43, no. 1 (2013): 63–84, p. 77.

[44] Vincent, Two-timing modernity, p. 100.

[45] Aoyama, 'BL (boys' love) literacy,' p. 69.

[46] Stephen Dodd, 'The significance of bodies in Sōseki's Kokoro,' Monumenta Nipponica vol. 53, no. 4 (1998): 473–98, p. 495.

[47] See Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Princeton, NJ, 2000, and what he calls the 'History 2s' that haunt the 'History 1' of capital.

[48] Julia Kristeva, 'Women's time,' Signs vol. 7, no. 1 (1981): 13–35.

[49] Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture, London: Routledge, 1994. Bhabha finds, however, 'remarkable' Kristeva's insistence that a 'gendered sign' can hold together 'such exorbitant historical times' (pp. 219–20).

[50] Takahara Eiri, Muku no chikara: 'shōnen' hyōshō bungakuron, Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2003. Cited in Vincent, Two-Timing Modernity, p. 8.

[51] Nagaike Kazumi, 'Matsuura Rieko's The Reverse Vision,' in Girl Reading Girl in Japan, ed. Tomoko Aoyama and Barbara Hartley, Routledge, New York, 2010, pp. 107–18; Nagaike, Fantasies of Cross-dressing, p. 99.

[52] 'Fujoshi' (腐女子), or 'rotten girl,' first coined by the Japanese media in the 1990s and then reclaimed by fans, is a homophonous pun on fujoshi (婦女子), meaning 'lady.' In China, funü (腐女) was adapted. A male version for yaoi consumers—fudanshi, or 'rotten boy'—came into use in mid-2000s Japan.

[53] Patrick Galbraith, 'Fujoshi: Fantasy play and transgressive intimacy among 'rotten girls' in contemporary Japan,' Signs vol. 37, no. 1 (2011): 211–32, p. 228.

[54] Rebecca Sutter, 'Gender bending and exoticism in Japanese girls' comics,' Asian Studies Review vol. 37, no.4 (2013): 546–58, pp. 548–50.

[55] For this view, see Matsui Midori, 'Little girls were little boys: Displaced femininity in the representation of girls' comics,' in Feminism and the Politics of Difference ed. Sneja Gunew and Anna Yeatman, St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1993, pp. 177–96.

[56] Nagaike, Fantasies of Cross-dressing, pp. 32–33.

[57] Nagaike, Fantasies of Cross-dressing, p. 15. To be clear, the anxious ego that yaoi quells is not one of Freudian female 'lack,' or penis-envy. Rather, as per Lacanian psychoanalysis, desire (in general) constantly emerges to quell the subject who is anxious from a 'lack of a lack,' or the constant threat that the 'Other' (the 'mother') will engulf the subject. Borrowing from Martin Heidegger's notion of 'thrownness,' anxiety for Jacques Lacan is the temperament of all subjects thrown into the world at infancy.

[58] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, New York: HarperPerennial, 1994, p. 36.

[59] Valérie Cools, 'The phenomenology of contemporary mainstream manga,' Image & Narrative vol. 12, no. 1 (2011): 63–82, online: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/126/97 (accessed 1 September 2014).

[60] Fujimoto Yukari as quoted in Aoyama Tomoko, 'Eureka discovers Culture Girls, Fujoshi, and BL: Essay review of three issues of the Japanese Literary Magazine, Yuriika (Eureka),' Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific no. 20 (2009), paragraph 15, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue20/aoyama.htm (accessed 1 September 2014).

[61] Martin, 'Girls who love boys' love,' pp. 372, 374–75.

[62] See Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics, New York: Zone Books, 2002.

[63] Mizoguchi, Reading and Living Yaoi, p. 380.

[64] Azuma, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, p. 72.

[65] Huat, 'Conceptualizing an East Asian popular culture,' p. 206.

[66] Gabriella Lukács, Scripted Affects, Branded Selves: Television, Subjectivity, and Capitalism in 1990s Japan, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

[67] Some fans have joked that the early dōjinshi were comprised of only violent sex scenes, so 'yamete, oshiri ga itai' ['stop, my ass hurts!'] is a more suitable phrase for the acronym. Lunsung, 'Yaoi Ronsō,' paragraph 9.

[68] I turn to Walter Benjamin in my formulation of the materiality of moe, following Azuma, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, pp. 58–59, who notes that database culture was alluded to by Benjamin as early as his 1936 discussion of the 'loss of the aura' in an age of mechanical reproduction; otaku consume 'derivatives' as much as 'originals,' seeing little distinction between the two.

[69] Anne Allison, 'New-age fetishes, monsters, and friends: Pokémon in the age of millennial capitalism,' in Japan after Japan, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 331–57, p. 353.

[70] Honda Touru as summarised in Patrick Galbraith, 'Moe: Exploring virtual potential in post-millennial Japan,' Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies vol. 9, no. 3 (2009), online: http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2009/Galbraith.html (accessed 1 September 2014).

[71] See John Treat, 'Yoshimoto Banana writes home: Shojo culture and the nostalgic subject,' Journal of Japanese Studies vol. 19, no. 2 (1993): 353–87, p. 363.

[72] Azuma, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, pp. 86–87.

[73] Azuma, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, p. 137n63.

[74] Azuma, Otaku: Japan's Database Animals, p. 137n63.

[75] Galbraith, 'Moe: Exploring virtual potential in post-millennial Japan.'

[76] Keith Vincent, 'Translator's Introduction' to Saitō Tamaki, Beautiful Fighting Girl, trans. Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, pp. xxiv–xxv.

[77] See Slavoj Žižek, Organs Without Bodies: On Deleuze and Consequences, New York: Routledge, 2003.

[78] See Elizabeth Grosz, 'A thousand tiny sexes: Feminism and rhizomatics,' Topoi vol. 12 no. 2 (1993): 167–79.

[79] Petrus Lui, 'Queer Marxism in Taiwan,' Inter-Asia Cultural Studies vol. 8, no. 4 (2007): 517–39, p. 520.

[80] 'Interview with Ang Lee,' CNN website, 26 October 2007, online: http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/10/08/talkasia.anglee/ (accessed 1 September 2014).

[81] 'Socially conservative Singapore bans popular gay-oriented Taiwanese film,' Taiwan Times, 23 July 2004, online: http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2004/07/23/2003180053 (accessed 1 September 2014).

[82] 'Singapore censor passes Brokeback,' BBC News (website), 15 February 2006, online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4716610.stm (accessed 1 September 2014).

[83] 'More action less cut,' Today (Singapore), 4 November 2005.

[84] Brian Wu, 'Formula 17: Mainstream in the margins,' in Chinese Films in Focus II, ed. Chris Berry, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, pp. 121–27, p. 124.

[85] Wu, 'Formula 17,' pp. 122–23.

[86] Wu, 'Formula 17,' p. 126.

[87] The King and the Clown (왕의 남자), Dir. Lee Joon-ik, Cinema Service, 2005; No Regret (후회하지 않아), Dir. Lee Song-hee-il, CJ Entertainment, 2006.

[88] Jeeyoung Shin, 'Male homosexuality in The King and the Clown: Hybrid construction and contested meanings,' The Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 18, no. 1 (2013): pp. 89–114. Shin writes of the rise of kkonminam (roughly translated, 'metrosexual') masculinity and the growing popularity of Japanese yaoi as signs of the power and currency of women's consumerism in today's South Korea. Regarding The King and the Clown, Shin writes of the fine line between homosociality and homoeroticism in the film as it manifests in the space of namsadang (or all-male travelling performance troupes from the Chosŏn period, similar to kabuki theatre in Japan and the Peking opera in China). In a New York Times interview, Director Lee Joon-ik explained that the tongsŏngae ('same-sex love') depicted in the King and the Clown was not 'homosexuality defined by the West' (i.e., an 'orientation') but was contexualised within namsadang. Yet, as Shin explains, namsadang never achieved the status of a respected art form in Korea; unlike kabuki or Peking opera, its performers were not admired as talented artists.

Shin thus sees a cinematic influence between the trope of Peking opera, such as found in the popular 1993 Chinese film Farewell, My Concubine (a film well-received in South Korea), and the trope of namsadang in The King and the Clown. The concept of an all-male performance troupe offered a speculative historical theme to bring queer kinship to a mainstream (read: relatively conservative) South Korean audience. Shin writes that this Sinophone connection as well as the growing popularity of Japanese yaoi demonstrate the importance of thinking regionally on matters of queer East Asian cinema. My interest also lies in the use of speculative queer kinship as a regional nation-building practice.

[89] See Chris Berry, 'Asian values, family values: Film, video, and lesbian and gay identities,' Journal of Homosexuality vol. 40 nos 3/4 (2001): 211–31.

[90] Huat, 'Conceptualizing an East Asian popular culture,' p. 217.

|