Femme Infantile:

Australian Lolitas in Theory and Practice

Sophia Staite

Introduction

-

This paper explores a community in Australia that is centred on Lolita fashion. Lolitas are not a subset of cosplayers, although Lolita is playing with costumes. For girls who practice Lolita, I argue that the clothing represents neither an infantile clinging to childhood nor a rejection of adult sexualities. Based on interviews with Australian Lolitas and supplemental material from online English-language Lolita communities, I argue that Lolita in the Anglophone, Australian context is an act of temporally dislocated class-play. Rather than dressing up as someone else, Lolitas are expressing who they feel themselves to be by clothing themselves in a way that communicates the privilege, leisure and indulgence associated with period nobility. It is no coincidence that the anachronistic style of Lolita clothing is most heavily influenced by European aristocratic costume from the Victorian era. Lolita reflects the fashion of the daughters of the colonial powers; powers whose impact on the course of Asian-Pacific history was profound. Lolitas dress like the daughters of Queen Victoria, Empress of India. Lolita is a yearning for a lifestyle of leisure and indulgence; the self-indulgence permitted by complete economic security rather than the indulgence a child receives from her parents. I argue that this identity is particularly attractive to girls because of the combination of structurally reinforced disadvantage and the concurrent discourse of feminine self-empowerment that obscures that disadvantage. The analytical emphasis of Lolita/Lolitas in both academic and journalistic writing on (a) sexuality and infantilisation has created a set of self-perpetuating blinkers that leave questions of inequality and privilege largely unexplored. This paper uses ethnographic data to combat the sex-phobic child-woman paradigm in the Australian setting, emphasising instead the significance Lolitas themselves attribute to the classed aspects of their lifestyle.

-

Ethnographic data is taken from structured interviews conducted in 2009 with twelve Australian Lolitas, principally from Tasmania and Victoria. After the conclusion of the interviews, many of the participants spent additional time showing me their favourite Lolita-related places in their hometowns and sharing meals with me. It was during this more free-flowing interaction that their economic circumstances became apparent, rather than in the formal interviews. Participants were self-selecting, having responded to a request for interviews posted in an online Lolita community or to my request for participation in person following a national fashion event in Hobart, Tasmania, in 2009. Their responses provide considerable insight into their individual experiences as Lolitas and are indicative of the beliefs and practices of the Australian (and to some extend the Anglophone) Lolita community more broadly. They are not, however, demographically representative (only two of the twelve were teenagers, for example), nor is the sample size significantly large. Therefore the nature of these research findings is preliminary rather than conclusive. Supplemental data is taken from the online community sites livejournal.com and Lolitafashion.org. While I use the catchall term 'Lolitas' (and 'Lolita' to refer to the style or culture rather than its practitioners), the Lolitas I write about are Anglophone and predominantly Australian. Because they represent the overwhelming majority, I assume that Lolitas are female. I do not want to obscure the existence of male Lolitas (so-called Brolitas) or minimise their contributions to and participation in Lolita communities, but their experiences and motivations differ substantially from those of their female counterparts. It is not within the scope of this paper to unpack those complexities.

Costume play, but not cosplay

Having an ignorant mother who doesn't want to acknowledge Lolita and calls it 'cosplay' is really tiring … so I think to myself.[1]

-

What does Lolita look like and who 'does' Lolita in Australia? The following is taken from an Australia Lolita website:

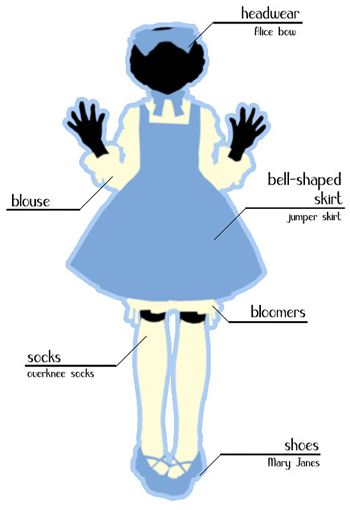

A lolita outfit is composed of basic key elements. These can be broken down into: headwear, blouse, bell-shaped skirt, undergarment, legs, and footwear. Each element is essential in creating the proper lolita aesthetic, but as you will see, there is much room for variety within them. Although none of these can be called absolute necessities, remember that coordinating a lolita outfit is a bit like making a cake. You can take away or replace a couple of ingredients, but if you take away the butter, the sugar, and the milk, it just stops being cake.[2]

-

There are numerous sub-categories of Lolita, the most well known being Elegant Gothic Lolita or EGL.

| |

This is so much the case that EGL is often mistaken as representative of the whole style. All versions (with the exception of the boy style Kodana, which uses breeches but is usually worn by girls) share this basic silhouette. While the clothing is the core focus of the Lolita community, Lolitas typically participate in activities (both alone and when together) that correspond with the image of a Victorian-era upper-class girl. Typical activities include picnics, ice skating, embroidery and tea parties. Some Lolitas collect dolls and enjoy sewing miniature Lolita outfits for them and photographing them in creative settings.

Figure 1. Anatomy of a Lolita outfit. Source. 'Anatomy,' Lolita Fashion, n.d., online, http://www.lolitafashion.org/anatomy.php, accessed 10 March 2011.

|

-

My initial expectation going into research about Lolita was that it was a subset of the general 'Japan Cool' boom in Australia and that the Lolita community would overlap (perhaps to the point of being entirely contained within) the cosplay community. This is in fact not the case. Although many Lolitas in Australia discovered the style through a pre-existing interest in Japan, particularly anime, a sizable subset come from the Gothic or Steampunk communities.[3] Those Lolitas who are also cosplayers draw a very clear distinction between the two. As Isaac Gagné's Japanese informants explained to him, '[cosplay] means mimicry and dressing up as someone, that is, as a specific character … their own Gothic/Lolita style was personalized and was an expression of their "true selves".'[4] This emphasis on Lolita as an expression of 'true self' is also a strong theme in the Anglophone community. A number of Lolitas expressed to me frustration at phrases such as 'dressing up as a Lolita' or 'cosplaying as a Lolita.' They did not view their Lolita clothing as more or less a costume than any other clothing; an important distinction I will examine more closely later in this paper.

-

A second important difference from cosplay is the focus on practice. Cosplay is a public activity. Cosplayers dress to be seen by others at conventions, photo shoots, club meetings and so on. It is difficult to imagine someone cosplaying at home alone or when meeting a friend for brunch at a café. It is an essential part of cosplay to role-play the character that one is representing. Lolitas wear their clothes to school, to bowling allies and at home when they are alone. Lolita media—including websites, magazines, blogs and vlogs—contain a plethora of tips and ideas for adding Lolita touches to everyday items such as school bags. The intersections of work and play, real and fantasy are many and complex in Lolitas' lives. For this reason I am somewhat cautious about Theresa Winge's characterisation of Lolita as carnivalesque.[5] Lolita, even when it involves play and fantasy, is part of the everyday practice of these girls and women rather than a temporary suspension of the usual. When it is given a performance aspect, as in the 'fruits fashion' event where I recruited a number of the interview subjects for this research, those who participated in Lolita dress were nevertheless explicit during the judges' question section of the contest about their commitment to Lolita clothing in every-day life. The judges asked each Lolita about how frequently she dressed in Lolita and in what range of situations she had worn the outfit she was competing in. The answers to these questions seemed to bear considerable weight in the judges' decisions.

-

Australian Lolitas do share an important characteristic with their cosplaying cousins, however—sewing. For those familiar with Lolita primarily through Japanese sources, which often focus on expensive brands such as Baby, the Stars Shine Bright, the emphasis on sewing and DIY in the Australian community comes as a surprise. Japanese brands and cheaper imitations are widely accessible to Australian Lolitas via online stores. Nevertheless, handmade outfits are given the highest honours in competitions and Lolitas who sew from scratch appear to have higher status in the community. Although there are ideological components to this, it is also telling that the majority of my sources come from working-class backgrounds. I argue that Lolita is particularly attractive in Australia to girls with lower socio-economic status. The significance of sewing is explored in greater depth later in this paper.

Lophelia

What ails the Lolitas, along with many young women in Japan, is a sense of insecurity.[6]

-

In newspaper articles and popular commentary (which focuses on Japanese Lolitas to the point of describing Lolita as an 'only in Japan' phenomenon), Lolita is portrayed as a rejection of adulthood. Lolitas themselves are depicted as rejecting adult social roles, being sexually insecure and clinging to childhood. One article reports that Lolita is 'connected to a longing for childhood security,'[7] while a Wall Street Journal article quotes psychologist Yo Yahata, who claims that 'dressing up like this and having people stare at them makes them feel their existence is worth something.'[8] In part, Lolitas' association with tea parties and dolls contributes to the link so many observers make with childishness. Overwhelmingly, however, the clothing is responsible. Numerous newspaper articles describe Japanese Lolitas as dressing like little girls. In Australia, too, Lolitas report hearing their dresses described as baby clothes, dolls' clothes or Little Bo Peep costumes.

-

This coding of Lolita clothing as children's clothing is quite peculiar when examined more closely. Although the silhouette is based on that of nineteenth-century children's wear, very few little girls regularly wear long dresses

| |

with puffy sleeves these days. Contemporary children's fashion is all about miniaturised adult clothing,[9] pantaloons and panniers are not common underwear at any age. Tea parties, at least according to my nieces, would only be fun if there were a Nintendo version. When commentators describe all of the 'child-like' aspects of Lolita, they are not thinking about the reality of contemporary children's lives. To take another example, the dolls of Lolita culture are not the dolls of actual children. The doll of choice for Lolitas is the Super Dollfie, an anatomically correct doll for whom brands such as Baby, the Stars Shine Bright release miniature versions of their collections. Super Dollfies are not intended for children and are priced beyond childhood affordability. They are slightly unsettling; with translucent, almost organic feeling 'skin' and they are completely customisable.

Figure 2. Unclothed Super Dollfie. Source. 'Super Dollfie,' on Flickr, n.d., online: http://www.flickr.com/photos/niomi/150950642/in/photostream, accessed 2 July 2013.

|

-

There is a certain aspect of childishness in Lolita culture, but not a conception of childhood that assumes purity and passivity. Monden Masafumi writes, 'Lolitas also tend to endorse the egoism and cruelty associated with childhood rather than its innocence, naïveté or submissiveness.'[10] What critics mean by childishness is often related to social roles, not, as I have argued, with the everyday lives of children. Perhaps because subcultural participation is widely accepted as a transitory phase in the process of growing up, Lolita is seen as something that should be grown out of quickly.

-

These portrayals of Lolitas as insecure and infantile are part of a broader trend of young people being infantilised as a result of their disassociation from employment and financial resources.[11] The tendency to infantilise is even stronger when girls are the focus. I argue that the emphasis on immaturity and insecurity in media and some academic conceptualisations represents a distillation of wider discourses of girlhood. This way of conceptualising girlhood becomes condensed and intensified when it collides with Lolita's ultra-girlish style. Marnina Gonick identifies two dominant discourses of girlhood, which she terms 'Girl Power' and 'Reviving Ophelia.'[12] The girls of Girl Power can do anything they want to if they put their minds to it, while fragile Ophelias suffer a crisis of identity leading to disordered development. She writes that femininity is rearticulated 'as comprising both powerful ambitions for autonomy and vulnerability so extreme as to threaten extinction.'[13] Rather than seeing the two as opposites, Gonick sees them as interrelated discourses:

Girl Power and Reviving Ophelia participate in the production of the neoliberal girl subject with the former representing the idealized form of the self-determining individual and the latter personifying an anxiety about those who are unsuccessful in producing themselves in this way. Both participate in processes of individualization that … as we will see, direct attention from structural explanations for inequality towards explanations of personal circumstances and personality traits.[14]

-

Lolitas seem to personify Ophelia revived. Gonick takes Reviving Ophelia from Mary Pipher's widely read 1994 book of the same title.[15] Pipher argues that at puberty American girls feel pressured to split their 'true selves' from the selves that they think others expect of them.[16] They become disoriented, depressed 'female impersonators.'[17] Lolitas appear to many commentators to have taken this to the extreme: retreating into an overblown parody of childhood to avoid adulthood. If girls can achieve anything they want, it follows that failure to do so should be seen as personal failure.

Sex and the atemporal girl

Dressing this way takes a certain kind of ownership of one's own sexuality that wearing expected or regular things just does not. It doesn't take a lot of moxie to put on a pencil skirt and flats.[18]

-

In response to the question, 'Do you consider yourself to be 'girlie' or feminine outside of Lolita?' a number of respondents simply answered 'yes,' while others elaborated or qualified their answers. One Lolita responded, 'In a way, Lolita helps me to remind people that, although I adhere to the rules and don't speak my mind very often, I'm not a clone: I've made a choice to dress this way and dressing this way makes me happy.'[19] Another saw Lolita as an umbrella under which woman and girls feel free to enjoy pastimes that may otherwise be belittled because of their associations with femininity:

[The] longer one has been wearing Lolita, the more interested in the arts they usually become, such as learning to sew, learning to draw, or playing a musical instrument, baking, going to college or uni and studying fashion, jewellery making, cross stitch even! However I think a lot of people have been drawn to the fashion because they have done one or more of those things in the past or when they were young and want to revisit it; others because they feel Lolita helps them justify these activities.[20]

-

For others, Lolita was the only time they presented a feminine image, as exemplified by the following exchange with a twenty-two-year-old Lolita who works in a supermarket:

Lolita: I like fashion in general and I like clothes and I like frills basically; and ribbons and lace and pretty things.

Interviewer: So would you describe yourself as being girlie when you're not being a Lolita?

Lolita: [Laughs] No. Noooooooo. Unfortunately, no, quite the opposite.

Interviewer: Why unfortunately?

Lolita: Aw, 'cause I get a lot of shit about being too masculine so it, it's pretty funny.

-

Femininity has a complex relationship with the pleasures and self-identity of Lolitas. One aspect that did not feature at all, in a single response, was men. There is no mention of what men may think of Lolita; no desire expressed to either attract or scare off men. These Lolitas are not 'thumbing their noses at men,'[21] nor 'appealing to a pedophile's [sic] standard of beauty.'[22] Men are simply irrelevant. Nevertheless, in academic works that focus on the figure of the Lolita herself, there is a fascination with sex—the sex Lolitas aren't having, the sex they should be having, and occasionally the sex other parties would like to have with them. In large part I believe this obsession with Lolitas' supposed sexual abstinence is a continuation of the pervasive (although hotly contested) notion of the shōjo as sexless. Lolita, associated with girls and young women and an overwhelmingly homosocial culture, is often considered a subset of shōjo culture.

-

In some academic writing, the sexuality of Lolitas is highlighted, with infantilisation occurring as a result of an emphasis on sexual maladjustment. As Catherine Driscoll points out, 'feminine adolescence has been overwhelmingly explicated as a sexualised mode of development, and studies of girls and girlhood have perpetuated an emphatic association between sex and girls.'[23] At the same time, the sexuality of girls is heavily classed. Valerie Walkerdine highlights the influence of socio-economic status in differing reactions to a television talent program, which was criticised in broadsheet newspapers but celebrated in the tabloids. She writes,

[T]he eroticized little girl presents a fantasy of otherness to the little working-class girl … from flower-girl to princess, so to speak. Such a transformation is necessarily no part of middle-class discourse, fantasy and aspiration. Rather, childhood for the middle class is a state to be preserved free from economic intrusion.[24]

-

Vera Mackie speculates that for Lolitas, 'their reaction to the conundrum of adult sexuality is to attempt to prolong their girlhood.'[25] Analysing the popular Lolita novel Shimotsuma Monogatari, Mackie describes what she interprets as horror 'directed at both the sexuality of the adult woman, and the potential for her body to become a maternal body.'[26] In Mackie's interpretation the narrator of the novel, a Lolita named Momoko, is 'infatuated' with Lolita; horrified by sex and 'the potential for her body to become a maternal body' and afraid of becoming an adult.[27] The use of such visceral language conveys that Momoko is phobic and developmentally stunted. She is failing to master her body in an appropriately heterosexual way (her disgust being directed, apparently, at both the male body and the maternal body). Mackie writes about, 'the young woman's horror of the adult woman's body. This horror is directed at both the sexuality of the adult woman, and the potential for her body to become a maternal body. The agony of labor is fused with the ecstasy of sexual excitement, an image that brilliantly fuses the two elements of the young girl's—the shōjo's—fear of becoming an adult woman.'[28]

-

This interpretation is later followed by the observation that 'the novel closes with neither Ichigo nor Momoko having been initiated into heterosexuality.'[29] It is important to critically dissect the assumptions underlying this sentence. Here, sexuality is a product of sex; the girls cannot be heterosexual until 'initiated' by a man. Heterosexuality is an inevitable end-point, which the characters have not yet reached but eventually it is assumed that they will. Mackie references a 'possible escape from the girlscape,' quoting Momoko saying that growing up might not be so bad after all.[30] Coming immediately after the initiation comment, this implies that 'growing up' requires 'initiation' through heterosexual intercourse. Womanhood, in other words, is a status conferred upon a girl only after her deflowering.[31] Once this has happened the Lolita presumably hangs up her bonnet for good. As Driscoll points out, the 'hymen underscores the inscription of virginity on and as a feminine body, [and is] credited with social and psychological import as a border between girl and woman.'[32] In order to remain a Lolita, an intact hymen is necessary. Therefore the possibility of penetration is imminent and fearful for Lolitas, in Mackie's telling. She writes, 'The clinging to the innocence of the shōjo, then, is a rejection of the fate of defloration, of being reduced to a sexualized body, of the potential transformation into a maternal body.'[33] This phrasing suggests that the Lolita has no investment in or control over the sexualised body. She is given no space to own and enjoy her sexuality or to initiate sex. If she accepts a sexual role it will be passive: she will be deflowered, transformed and reduced by an unseen but apparently all-powerful phallus.

-

Although Mackie's is a literary analysis and Momoko is a fictional character, the same tropes and assumptions inform writings about living Lolitas (particularly in newspaper articles). In the case of Lolita, socio-economic status and other macro-frames are obscured by the micro focus favoured in analyses such as this. Momoko fears the transformation of her body through pregnancy in Mackie's account because she is afraid of adulthood, not because teen pregnancy would trap her in the semi-rural suburbs and the working-class society that she despises. In Mackie's reading, Momoko's embroidery skills are not the basis for a vocation, allowing access into a class above that of her fraternal family; instead they become an intertextual link to another sex-phobic girl (Dazai's Joseito), further reinforcing the claim of Momoko's sexual immaturity.[34] Time and again throughout Shimotsuma Monogatari, Momoko dwells on the economic forces influencing the behaviour of other characters. This is not to dismiss Mackie's analysis of Shimotsuma Monogatari on a textual level. What I want to highlight is how the focus on personal, individual flaws blinkers us to broader social issues facing real living Lolitas. As Joanne Baker argues in Great Expectations and Post-Feminist Accountability, there is an assumption in Australian society that gender equality has been achieved, with awareness of entrenched disadvantage replaced by 'discourses of limitless possibility and the rewards of individual effort and personal transformation [that] are expressed by young women and cut across parenting status and educational attainment as well as race and class,' resulting in 'the pervasive, unforgiving and frequently anxiety-ridden obligation to account for the circumstances of their lives in individualised terms—regardless of how difficult they might be.[35]

-

The idea of Lolitas as asexual or phobic about maternal bodies is derived in Mackie's work from semiotic decoding of the dress style and textual analysis of a fictional story. Those ideas are not applicable to the Anglophone community (and are not intended to be), as a very basic Internet search demonstrates. By far the most commonly cited resource for Lolitas by my interviewees was livejournal.com. A few searches through posts to the site quickly dispel the idea of Lolita as a rejection of sexual or physical maturity. For example, there are literally hundreds of threads in which Lolitas discuss their boyfriends, share pictures of themselves with their boyfriends and discuss the impact of Lolita on their relationships. The community is not restricted to heterosexual relationship discussion, of course. In fact, two sub-communities that are particularly notable are Lolita Pride, which boasts 446 members of all sexual orientations, and Lolita Love Letters), a Lesbian Lolita hook-up community with 51 members as at 20 October 2011.

-

Regarding the loathing of sexual, maternal bodies, there are several pages of Lolitas asking for advice on Lolita maternity clothing. A number of people share their experiences of modifying Lolita outfits to accommodate their changing bodies, and all of the responses are positive and encouraging.[36] One person comments, 'Lolita is a celebration of femininity and what could be more feminine than being pregnant? I say go for it, I think it's an adorable idea!' In a thread discussing raising children without giving up Lolita a woman shares a picture of herself with her son and writes, 'One of the most important lessons you can teach a child is that it's OK to be yourself. Even if others think you're a little weird.'[37] The same thread provides a link to an entire community dedicated to older Lolitas, some with children.[38]

Figure 3. Pregnant Lolitas. Source. 'Starry Candy Box and the Oneesan Inc and the Fancy French Event,' Kalamarikastle.com, 6 September 2010, online: http://kalamarikastle.com/?p=429, accessed 2 July 2013.

| |

Figure 4: Lolita and Child. Source. Pink_Emmie_Bat, flickr, n.d., online: http://www.flickr.com/photos/indrasarrow/371820315/sizes/l/in/set-72157594143769925/, accessed 2 July 2013. Used with permission.

|

-

This evidence suggests that Mackie's analysis of the characteristics and motivations of the fictional Lolita character Momoko, despite providing a valuable starting point for investigation, is not broadly transferable to Australian Lolitas. Nor are Mackie's broader speculations about the relationship between Lolita and sexual insecurity applicable in the Anglophone setting.[39] This is not intended as a criticism; Mackie is not addressing Australian Lolita practices or societal reactions to Lolitas. She explores a different set of questions within a different disciplinary perspective to that presented in this paper. What the differences highlight is the way that the convergence of class, age and gender determine the ways we talk about Lolitas. The differences between the image of Lolita derived from Mackie's textual analysis and the real-world examples of Lolita attitudes relating to sexuality and motherhood reveal that there is a conversation which is currently not occurring about the role of girls in contemporary society and the way the language of empowerment has individualised their failures by obscuring the barriers that stand in the way of their achievements. Lolitas lose individual personhood and are reduced to bodies and fears about bodies. Their definitive characteristic becomes the stubborn presence of an imagined hymen.

Dollhouses with glass ceilings

Gothic/Lolitas I spoke with virulently denied any connection to maids, however, claiming that the crucial difference (beyond that of the maid's vastly inferior clothing style and quality) was that maids 'served' people, whereas Gothic/Lolitas 'were served' (because they are princesses).'[40]

-

Many authors have focused on the asexual style of Lolita clothing, while the significance of its impracticality has been largely unexplored. In Lolita, everything is impractical because of its excess, with no other connotation beyond self-indulgence. The significance of all the ruffles and lace was not something I had considered; in fact it is something that emerged only through the interview process. Contrary to my expectations, based on the cost of Lolita brand-name clothing, most of my interviewees were from working or lower-middle class income brackets and expressed little expectation of upward mobility. Very few academic sources contain ethnographic data derived from actual (as opposed to fictional or hypothetical) Lolitas. Since online discussion focuses on sewing tips and debating colour choices, it is not surprising that a sense of socio-economic disadvantage is not immediately apparent in these discussions (and of course, being online in the first place requires access to certain infrastructures). Although few of my interviewees explicitly mentioned class, it came through very strongly in their descriptions of Lolita's appeal. The identity that they associate with Lolita is neither infantile nor asexual, but rather one of leisure and privilege. The following comment most clearly articulates this attraction, 'Fashions used to be a mark of status. Both men and women of the upper classes would wear elaborate and pale coloured clothes to make it clear they had no work that would threaten the integrity of their delicate fashions, no dirty work. So sometimes it's nice to pretend to be glamorous and decorative and far away from work.'[41]

-

This statement has greater emotional significance than the written word expresses. Many of the Lolitas I interviewed were in situations of serious financial hardship. For example, one was working extremely hard making Lolita accessories for sale to try and save the family home from repossession after her single parent had been made redundant. She had tried to find work but the cost of petrol travelling from her isolated rural home to the nearest town offset the minimum wage jobs she was able to find. In her world away from work, Lolita, had become her last resort in attempting to provide income. While she and many other Lolitas describe their attraction to the aesthetic as a love of lace, ribbons and pretty things, I suspect that the difference between these soft, gentle and indulgent things and their circumstances, which often require them to be hard-nosed, aggressive and self-controlled, is a substantial attraction.

-

Although the Lolita in the above example has extended her production of Lolita items to include hats and accessories made for sale, she started out making such things for her own use. For Lolitas without access to much disposable income, homemade clothing and accessories are essential. A number of interviewees described the process of looking at brand-name websites or reading The Gothic & Lolita Bible for inspiration before making their own versions within tighter budgets.[42] Simon Jones observes a link between homemade clothing and self-esteem, 'There are a significant minority of young people who sew and knit their own clothes for reasons that are partly to do with pleasure in their own symbolic work and creativity as well as financial [considerations].… There is a symbolic as well as practical pleasure and sense of fulfilment for young people in being able to use their own manual skills and resources to make their own clothes.'[43]

-

Rather than being an expression of a rejection of adult social roles or sex or motherhood, my interview responses suggest that an as yet undiscussed factor is at play in the Australia Lolita community: socio-economic disadvantage. Many of the Lolitas I interviewed experienced a convergence of disadvantages. Their socio-economic backgrounds, family histories, gender and educational attainment all factor in limiting their future opportunities. Furthermore, the discourse of empowerment referred to earlier blames them for their circumstances. As Sheila Jeffereys writes, it is common to talk about women as though the 'material forces involved in structuring women's subordination have fallen away to leave liberation a project of individual willpower.'[44]

-

Anne McKnight reads Shimotsuma Monogatari in the context of the interaction between Rococo excess and revolutionary consciousness. McKnight's interpretation highlights what dreaming of a life of indulgence may mean for girls and the construction of their subcultures. For McKnight, Shimotsuma Monogatari is fundamentally a story of the marketplace. She writes that 'every sort of relationship in the novel and the film—except the bonds of the biker gang and Momoko's care for her elderly grandmother—is entirely enabled and resolved through the market.'[45] Lolita fashion, she writes, reprises 'the logic of the Rococo, the hallmark of the seventeenth-to-eighteenth-century "consumer revolution" that provided women an entry into the marketplace during the transition from a feudal to a bourgeois regime.'[46] Gender and class are deeply intertwined of course, and the bourgeois age came with its own systems of patriarchy. Kotani Mari argues that the culture of shōjo is rooted in the combination of class consciousness, economic prosperity and a 'cult of cultivation.'[47] She writes:

The patriarchy provided a necessary guarantee within the system that gave rise to the shojo [sic] as nurtured within pre-war schools for women. In other words, the shojo had economic and social status, or class. Yet in the shojo admired by so many intellectuals was a certain aggressiveness, which, while formed with the system, insofar as it was cultivated surreptitiously, ended up paradoxically possessing an aesthetic and sexual magic that shook the system.'[48]

-

Part of the nurturing of these shōjo was distancing them from economic concerns. The shōjo is protected by a boundary of economic stability.[49 Her life is concerned with pleasure and play. This is the life Australian Lolitas dream of. Rather than being part of a transnational shōjo culture, I see them as outsiders looking in with envy.

| |

The ugly realities of financial strife are partially obscured behind lace and ribbons, but never entirely erased from sight. Shimotsuma Monogatari's Momoko is also an outsider to the nurtured life of Kotani's pre-war shōjo. Her poverty is the foundational tension of the novel/film. The resolution achieved at the end depends on 'feminizing the crossover of media forms to make work compatible with play.'[50] This method of resolution is essential because 'the longing for class mobility sends Momoko straight to work' despite her belief that 'for one who lives with the rococo spirit, productive labour is to be avoided at all costs.'[51] For girls who are not protected by the bourgeois cocoon of shōjo culture, this seems an impossible dream. Only if work is recast as play, production as pleasure, can the dream be realised. In Shimotsuma Monogatari, 'the happy ending in which the story culminates is all about being able to turn the frivolous, aristocratic hobby of embroidery into a vocation, to transform hobby into work.'[52]

Figure 5. An Uneasy Fit. Source. 'im in ur feminism ruining ur discourse,' n.d., online: http://cache.gawkerassets.com/assets/images/39/2008/09/LOLita2.jpg, accessed 2 July 2013.

|

-

In the following comments, a Lolita who owns a business expresses frustration at the influence of her appearance over the way people respond to her, and describes using Lolita to take ownership of her appearance:

Although I am twenty-seven, I look perhaps sixteen to eighteen in average clothing. Often, people are condescending and assume I have no life experience whereas I have lived away from home since I was eighteen, done a bachelor's degree in accounting, marketing and Thai and have worked for small business, nationals and multinationals in accounting, media monitoring and market research client-side and operations in professional junior to mid-level roles in the last ten years prior to opening my store. It is frustrating. When I mention I have a business to non-Lolitas, many people take it upon themselves to lecture me as to how I should run it even though they have no experience in running a business, dealing with accountants, lawyers, customers and have no knowledge of the market or marketing. I find it arrogant. Therefore, I feel more comfortable liaising with people who do not think age determines how one should be treated; this is positive … in Lolita, looking young is an asset rather than a liability.[53]

-

The difficulties this businesswoman faced as a result of her girlish appearance are overcome not by attempting to make herself look older or more androgynous, but by opening a business trading in Lolita merchandise. Although the specifics of her story may be unusual, there remain a number of areas in which women are disadvantaged in the Australian economy. Young Australian women are faced with a situation in which women are more likely to be enrolled in full time study but less likely to find full time employment than men.[54] The average weekly earnings of young men are about 20 percent higher than those of young women, and according to an Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) report, 'although women are now more likely than men to be university graduates, they earn $2,000 a year less when they start work and continue to fall behind in wages and superannuation.'[55]

-

Japanese commentator and author Nakamura Usagi, cited in Bad Girls of Japan, claims that 'every woman is treated unequally because of her gender, class and nationality.'[56] Therefore, if buying brand name handbags or other designer goods 'helps us feel, even momentarily, like a winner in this not so fair world, then why not make use of it?'[57] The Australian Lolitas I interviewed were not in financial situations conducive to buying brand name goods. Nevertheless, I believe that the concept of feeling like a winner is important to understand the motivations of Lolita. What is interesting is that rather than buying fake brand name goods or in other ways attempting to replicate a higher socioeconomic lifestyle, Lolitas are sidestepping the contemporary social order and replacing it with an alternate set of values. Lolitas are the opposite of the 'nouveau riche'; they have the sole of nobility, the taste and dignity, irrespective of their financial circumstances. Their class-play is atemporal; their true selves exist in an anachronistic fantasy of the past created to serve the emotional needs of the present. In this new system, being poor is less of a social barrier than misjudging the compatibility of one's accessories. The ability to sew a complete outfit is valued more highly than the ability to afford a brand name outfit. Mary Bucholtz, writing about musical cultures, observes that they are

better understood as founded on a politics of distinction, in which musical taste is tied not only to pleasure or social identity but also to forms of power. This is a very different kind of oppositionality than is implied by the concept of resistance, for it is based not on a rejection of a powerless structural position but rather on a rejection of an undiscerning mainstream culture.[58]

-

The urge to reject the perceived characteristics of mainstream taste is derived from the desire for distinction in one's self-identity. As Sarah Thornton points out, 'Distinctions are never just assertions of equal difference; they usually entail some claim to authority and presume the inferiority of others.'[59] For young Australians struggling for various reasons to form a strong self-identity at the start of their adult lives, the ability to distinguish themselves from an 'inferior' group based on taste, a characteristic commonly held to be innate, is important. Subcultural capital is more achievable than economic or, in some cases, social capital. In Amy Wilkins' words, 'Young people develop oppositional identities with alternative … ways of feeling good about themselves that rely on criteria at which they can be competitive, rather than on institutional criteria at which they are likely to fail.'[60]

The gift of community

-

Lolitas interact within a vibrant international social space online, creating and debating the parameters of community and collective identity. The community is sustained by constant sharing activities, which generate subcultural capital in a form of a 'gift economy'. The accumulation of subcultural capital relies on constant gifting activity; one cannot be a Lolita passively. Uploading advice to new Lolitas, sharing carefully selected pictures of oneself and sewing flawless outfits are all time-consuming ways to accumulate Lolita capital. This requirement for participation in a range of gift-oriented activities is what lends Lolita its sense of community. Sewing is not a common skill in contemporary youth circles, but it is essential for a Lolita. So, Lolitas hold sewing bees; hosting parties where a community comes together to share skills, support creativity and add a social dimension to a repetitive task (the bell shaped skirt and amount of trimming on a Lolita outfit makes for a lot of uninspiring hem stitching).

-

Joshua Green and Henry Jenkins use Lewis Hyde's 1983 work The Gift to discuss the gift economy of 'viral' media sharing. They write,

Hyde sees commodity culture and the gift economy as alternative systems for measuring the merits of a transaction. He writes, 'A commodity has value.… A gift has worth'. By value, Hyde primarily means 'exchange value,' a rate at which goods and services can be exchanged for money. Such exchanges are measurable and quantifiable because they represent agreed upon standards and measurements. By worth, he means those qualities we associate with things on which 'you can't put a price.' Sometimes, we refer to what he is calling 'worth' as sentimental or symbolic value. It is not an estimate of what the thing costs but rather what it means to us.[61]

-

In the context of Lolita the gifts exchanged are not primarily physical objects but rather knowledge, access to information or shared labour. The worth of the gifts a Lolita is able to contribute to her community is entirely distinct from the value it they may have in the broader economy. While this is similar to Thornton's idea of subcultural capital, the community element of the gift economy sets it apart. While a Lolita may be admired and emulated because of her skilled accessorising or talent with a sewing machine, if she does not contribute to the community by sharing her skills and knowledge she is limited in the amount of subcultural capital she can accrue. Telling other Lolitas where you were able to find high quality lace at a low price or advising which shoes better suit an outfit are 'gifts' to the community as a whole and enhance the subcultural capital of the 'giver' in the process. The emphasis on this gift economy is what really makes Lolitas a community.

Conclusion

-

The dominant discourse about girls and girlhood lead to an unhelpful focus on immaturity and sexuality. The underlying assumption that girls are insecure and fragile encourages infantilisation and disenfranchisement, even as the concurrent belief in the individual's uninhibited ability to achieve anything obscures that disenfranchisement. The way Lolitas are written about highlights the conceptual challenge that their community poses to ways of articulating girlhood in contemporary society. While many authors have been drawn to investigate the sexual ramifications of Lolita globally, my research has shown that in the Australian context sexuality is not a dominant issue for Lolitas. I have argued that Lolita is a way of emotionally offsetting or rejecting the problems of hidden disadvantage. Lolitas create alternate criteria against which they are more likely to succeed, and support one another in a homosocial community sustained by a gift economy. Questions of financial freedom and alternative economies are far more important than whether or not Lolitas are sexually active. Beneath the frills and lace is a story about forging a self-identity through dress, an identity at odds with one's material circumstances and social expectations about how to conceptualise those circumstances.

Notes

[1] Lolita Blog cited in Isaac Gagné, 'urban princesses: performance and 'women's language' in Japan's Gothic/Lolita subculture,' in Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, vol. 18, no. 1, (2008): 130–50, p. 130.

[2] 'Anatomy of a Lolita outfit,' LolitaFashion.org for Lolitas of all styles, n.d., online: http://www.lolitafashion.org/anatomy.html, accessed 10 March 2009.

[3] As Jean Campbell explains, 'Steampunk is a fashion, design, and popular-culture phenomenon that combines romance and technology. Among its many influences are futurism, time travel, and the Victorian Age. These seemingly disparate facets combine into a resulting look that might be called "Mad Max meets Jane Austin."' Jean Campbell, Steampunk Style Jewelry: Victorian, Fantasy, and Mechanical Necklaces, Bracelets and Earrings, Minneapolis: Creative Publishing International, 2009, p. 9.

[4] Gagné, 'Urban Princesses,' p. 141.

[5] Theresa Winge, 'Undressing and dressing Loli: a search for the identity of the Japanese Lolita,' Mechademia, vol. 3 (2008): 47–63, p. 57.

[6] Veronica Chambers, Kickboxing Geishas: How Modern Japanese Women are Changing Their Nation, New York: Free Press, 2007, p. 33.

[7] Tracey Bond, 'Exploring the Loli-goth look,' the China Daily, 16 August 2007, online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/lifestyle/2007-08/16/content_6029995.htm, accessed 13 March 2010.

[8] Ginny Parker, 'The "Lolita Look" is making strides in Japan,' Wall Street Journal, 17 September 2004, http://cafe.gomorning.com/index.php?s=40c700c6553b954e03fa4f8d51b95607&act=attach&type=post&id=608, site accessed 21 August 2010.

[9] 'FashionKids,' FK Facebook, n.d., online: https://www.facebook.com/fashionkidss, is an excellent example.

[10] Masafumi Monden, 'Transcultural flow of demure aesthetics: examining cultural globalisation through Gothic & Lolita fashion,' in New Voices, vol. 2 (2008): 21–40, p. 28.

[11] Helen Reddington, '"Lady" punks in bands: a subculturette?,' in The Post-Subcultures Reader, ed. David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl, Oxford and New York: Berg, 2003, pp. 239–52, p. 239.

[12] Marnina Gonick, 'Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia": constituting the neoliberal girl subject,' Feminist Formations, vol. 18, no. 2 (2006): 1–23.

[13] Gonick, 'Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia",' p. 19.

[14] Gonick, 'Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia",' p. 2.

[15] Mary Pipher, Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls, New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons, 1994.

[16] Pipher, Reviving Ophelia, p. 27, cited in Gonick, 'Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia",' p. 12.

[17] Pipher, Reviving Ophelia, p. 27, cited in Gonick, 'Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia",' p. 12.

[18] Ellie, 'In her own words' in Dodai Stewart, Jezebel (2008), URL: http://jezebel.com/5056920/in-her-own-words, site accessed 28 December 2009.

[19] 'Imogen,' interview with author, 2008. Given how small the Lolita community is, there are confidentiality issues involved with including all relevant information regarding specific interviews.

[20] 'Portia,' interview with author, 2008.

[21] Eric Talmadge, 'Lolita subculture thumbs nose at men,' the Sydney Morning Herald, 4 August 2008, online: http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2008/08/04/1217701937784.html, accessed 13 March 2010.

[22] Dodai Stewart, 'Gothic Lolita style: rebellious? or regressive?' in Jezebel (2008), online: http://jezebel.com/5056235/gothic-lolita-style-rebellious-or-regressive, comments page, site accessed 28 December 2009.

[23] Catherine Driscoll, Girls: Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture and Cultural Theory, New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 139.

[24] Valerie Walkerdine, 'Popular culture and the eroticization of little girls,' in The Children's Culture Reader, ed. Henry Jenkins, New York and London: New York University Press, 1998, pp. 254–64, p. 263

[25] Vera Mackie, 'Transnational bricolage: Gothic Lolita and the political economy of fashion,' in

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific issue 20, (April 2009) para 24, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue20/mackie.htm, accessed 2 July 2013.

[26] Vera Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' in Girl Reading Girl in Japan, ed. Tomoko Aoyama and Barbara Hartley, London: Routledge, 2010, pp. 187–201, p. 187.

[27] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 187.

[28] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 187.

[29] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 197.

[30] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 197.

[31] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 199.

[32] Driscoll, Girls, p. 140.

[33] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 199.

[34] Mackie, 'Reading Lolita in Japan,' p. 192.

[35] Joanne Baker, 'Great expectations and post-feminist accountability: young women living up to the "successful girls" discourse,' Gender and Education, vol. 22, no. 1 (2009): 1–15, p. 2.

[36] See Kim, 'Wearing lolita while pregnant,' Livejournal, 29 September 2012, online: http://community.livejournal.com/egl/16299209.html, accessed 2 July 2013.

[37] Krystal, 'Kids and Lolita?' LiveJournal, 8 August 2008, online: http://community.livejournal.com/egl/11928042.html, accessed 2 July 2013.

[38] The URL for the group mentioned was http://community.livejournal.com/loli_oneesama, accessed 15 October 2010. However, it appears to have since disbanded.

[39] Mackie, 'Transnational bricolage,' para 25.

[40] Isaac Gagné, 'Urban princesses,' p. 141.

[41] 'Perdita,' interview with author, 2008.

[42] The Gothic & Lolita Bible is a quarterly Japanese fashion 'mook' dedicated to Lolita and Gothic fashion, published by Index Communications (Tokyo) as a spin-off of the fashion magazine Kera.

[43] Simon Jones, 'Style, fashion and symbolic creativity,' in Paul Willis, Common Culture: Symbolic Work at Play in the Everyday Cultures of the Young, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996, pp. 84–97, p. 15.

[44] Sheila Jeffereys, Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 19.

[45] Anne McKnight, 'Frenchness and transformation in Japanese subculture, 1972–2004,' Mechademia, vol. 5 (2010): 118–37, p. 119.

[46] McKnight, 'Frenchness and transformation in Japanese subculture,' p. 119.

[47] Mari Kotani, trans. Thomas LaMarre, 'Doll beauties and cosplay,' Mechademia, vol. 2 (2007): 49–62, p. 57.

[48] Kotani, 'Doll beauties and cosplay,' p. 57.

[49] Mari Kotani, trans. Miri Nakamura, 'Alien spaces and alien bodies in Japanese women's science fiction,' in Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams: Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime, ed. Christopher Bolton, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr. and Takayuki Tatsumi, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, pp. 47–73, p. 55.

[50] McKnight, 'Frenchness and transformation in Japanese subculture,' p. 136.

[51] McKnight, 'Frenchness and transformation in Japanese subculture,' p. 135.

[52] McKnight, 'Frenchness and Transformation in Japanese Subculture,' p. 135.

[53] 'Portia,' interview with author, 2008.

[54] Ben Schneiders, 'Women's pay worse than in 1985,' in the Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March 2010, online: http://www.smh.com.au/national/womens-pay-worse-than-in-1985-20100301-pdkr.html, accessed 15 April 2011.

[55] Schneiders, 'Women's pay worse than in 1985.'

[56] Cited in Jan Bardsley and Hiroko Hirakawa, 'Branded: bad girls go shopping,' in Bad Girls of Japan, ed. Laura Miller and Jan Bardsley, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, pp. 111–26, p. 118.

[57] Cited in Bardsley and Hirakawa, 'Branded: bad girls go shopping,' in Bad Girls of Japan, p. 118.

[58] Mary Bucholtz, 'Youth and cultural practice,' Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 31 (2002): 525–52, p. 541.

[59] Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995, p. 10.

[60] Amy Wilkins, Wannabes, Goths, and Christians: the Boundaries of Sex, Style, and Status, Chicago: 2008, The University of Chicago Press, p. 11.

[61] Joshua Green and Henry Jenkins, 'Spreadable media: how audiences create value and meaning in a networked economy,' in The Handbook of Media Audiences, ed. Virginia Nightingale, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 109–27, p 119.

|