Dancing in the Maelstrom of Chinese Modernity:

Jazz-Age Shanghai Cabarets as Sexual Contact Zones in Fact and Fiction

Andrew David Field

-

Between the 1920s and 1930s, the world of social dance halls or cabarets that flourished in Shanghai during the Chinese 'Jazz Age' became a significant social, cultural, and sexual arena for many of the city's diverse urbanites.[1] With its culture of social dancing that permitted close physical bodily contact, the cabaret provided a socially sanctioned venue for the public and private exploration of human sexuality. This paper aims to use erotic representations of Shanghai's cabaret culture that exist from or about that era to explore the concept of the Shanghai dance hall as a 'sexual contact zone,' arguing that this world of cabarets that arose and flourished in Shanghai helped to shape new patterns, templates and ideologies of urban social and sexual life in the modern Chinese metropolis.[2] The paper draws on a variety of primary source materials, ranging from popular to underground depictions of cabaret culture in the Chinese print media of the era as well as memoirs of that era published in later decades, to examine the sexual experiences and practices that emerged out of the city's cabaret culture.

-

The contact zone of Shanghai nightlife was constructed in the collective imaginary of fiction as well as on the physical dance floor.[3] Fiction also provides a window into aspects of the culture that are often clouded or obscured in other sources. This study thus makes use of several fictional depictions of the city's cabaret culture that focus on the sexual aspects of that culture. While fictional stories from the era highlight the erotically charged space of the Shanghai cabaret in the modern Chinese and western imaginations, other sources such as newspaper articles and advertisements do provide some evidence for the actuality of this space as an important sexual contact zone for Chinese urbanites, as well as (though far less frequently) between Chinese and foreigners living in the metropolis. What emerges from this study is a picture of a metropolis in which sexuality was both highly commercialised—dance halls were only one form of sexual enterprise that existed in a city in which prostitution was rampant—but also highly fluid, dynamic, ambiguous and mobile. In other words, while Shanghai cabarets and their thousands of Chinese hostesses have often been lumped into categories of sex work by scholars of Chinese sexuality, the ambiguous status of the cabaret and the cabaret hostess enabled a wider and more fluid range of social and sexual relations between men and women in the city that had existed under previous commercial institutions such as courtesan houses. As was the case in many western metropolises such as Paris, London, Chicago, New York and Berlin, it is clear that these spaces helped to pave the way for a looser set of social and sexual arrangements between male and female urbanites in the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai, one which necessitated the construction of new mores, identities and iconic depictions of this particular form of urban modernity.

Cabarets as sexual contact zones in the modern metropolis

-

Between the 1920s and 1940s, cabarets served as a key contact zone for facilitating casual sexual interactions between Chinese, and to a lesser extent between Chinese and/or other Asians and westerners living in the city. Cabarets in Shanghai facilitated casual contacts between young men and women and the cabaret became an important space for a new generation of Chinese urbanites in the city to explore their sexuality as they negotiated a new ethics of modern urban culture and society, involving more mobility and flexibility and greater choice in both sexual companions and marriage partners. That this struggle for sexual and social freedoms was occurring simultaneously to similar struggles being fought and won by youngsters in America and elsewhere is a testament to Shanghai's modernity and its ability to keep in time with trends in other metropolises such as Paris, London and New York.[4]

-

To be sure, western-style dance hall culture came to Shanghai via the bodies and practices of westerners who lived in the foreign settlements of that city and other ports of trade and commerce open to them. Dance halls in Shanghai were thus the product of the highly asymmetric encounter between the West and China, as embodied in the treaty port system of 1842–1943 in which Shanghai served as the key port city and in the regimes of knowledge and power that westerners (Europeans and Americans) brought to China during that epoch.[5] Several years after being introduced to the city by westerners, dance halls and their culture were eventually embraced by the more affluent members of Chinese society, which complicates the story of dance halls as a 'sexual contact zone' involving 'asymmetric' relations between foreign colonists and the 'colonised' Chinese.

-

During the Late Qing and Republican Eras, to be sure, Shanghai was well known in China and abroad for its sex industries. Certainly just about any sort of sexual service catering to many classes and types of male customers was available in neighbourhoods and 'red light districts' scattered throughout the city.[6] Why then should dance halls be such a special case of a 'sexual contact zone'? The great majority of dance halls in Shanghai were equivalent to taxi-dance halls in America,[7] whose women were employed by the management as professional dance partners; earning half the revenues of the dance tickets they earned each time they danced with a customer. These spaces provided an ambiguous sexual contact zone for urbanites, one that hovered dangerously and therefore enticingly between the realms of prostitution and respectable social intercourse. They also encouraged social mixing among both male and female patrons and above all, unlike most brothels these were very public spaces, forming a significant part of the city's public social culture as well as its cultural imaginary by the 1930s.

-

Drawing from a long history of paid female entertainment and sex work, many East Asian cities quickly adopted this modern American institution in a process that might be described as 'transculturation.'[8] By the 1920s, taxi-dance halls operated in Shanghai, Tokyo, Osaka, Manila and several other Asian cities.[9] While both Japanese and Chinese governments attempted to ban these dance halls in the late 1920s and '30s, they continued to flourish in Shanghai protected by the city's international zones.[10] By the 1930s, taxi-dance halls constituted the most popular form of nightlife in Shanghai, and after 1937 and the onset of the war with Japan, even most elite ballrooms had by necessity also been converted into taxi-dance halls offering hostesses for their male customers.[11] These were spaces where women were on conspicuous display as 'items' to be 'purchased' for their company by male customers—even the seating arrangements, where women sat in chairs neatly surrounding the dance floor, suggested a display of merchandise not unlike that of a modern department store, and it is certainly no coincidence that department stores such as Wing On and the Sun Company (two of the major department stores in Shanghai) featured dance halls which took up an entire floor of potential retail space.[12]

-

At least, the time and skills of these women on the dance floor could be purchased. It was not always the case that their sexual services could be purchased as well, although many cabaret hostesses at one time or other appear to have entered into some sort of financial relationship with their male customers involving intimacy outside of the

| |

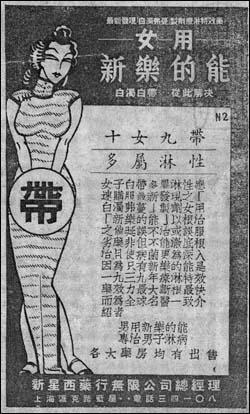

cabaret. Cabarets thus constituted an ambiguous and exciting form of public commercialised leisure and entertainment for the city's largely male population. Research on these dance halls as well as others in major metropolises around the world strongly indicates that while the women who worked in these establishments were not necessarily directly exchanging sex for money, many of them, perhaps the great majority of them, were nevertheless sexually 'available' to their male patrons given the right circumstances. Some sources suggest that cabaret hostesses and patrons were having sexual intercourse frequently and possibly with multiple partners. For example, a magazine containing images and stories about cabaret hostesses published in 1939 contains several advertisements for medicines that allegedly protected women against venereal disease.[13] One such advertisement for a medicine against gonorrhea (linbing) shows a finely proportioned woman dressed in a qipao holding a circle with the character 'belt' (dai) in front of her reproductive organs. These and other advertisements found in such magazines indicate that many hostesses were suffering from sexually contracted diseases, one of many occupational hazards that went with the job of hostessing.

Figure 1. Advertisement for venereal disease medicine. Shanghai wuxing zhaoxiang ji (a collection of photographs of Shanghai dance stars), Shanghai, 1939, p. 94. Image courtesy of Shanghai Municipal Library.

|

-

However, while the tabloid news stories of the era do suggest that many hostesses did engage in social and sexual relations with patrons outside of the dance halls, sometimes involving financial support of some sort or other, understanding what sorts of sexual behaviours dance halls encouraged is made rather difficult by the lack of data on the actual sexual activities that took place either inside the cabarets or outside of them between male customers and female cabaret hostesses. While dozens of Chinese newspapers, magazines and novels from the era describe in significant detail the world of cabarets in Shanghai, including relationships between cabaret hostesses and their male patrons, nevertheless very little is said about the specifics of sexual encounters. Information that is presented about sexuality is most often done so in an oblique way, alluding to but not explicitly relating the sexual side of the cabaret experience. Among a set of over four hundred articles on Shanghai cabaret culture over the period 1930–1940 that I surveyed in the Crystal (jingbao), one of the leading tabloid journals or xiaobao from the era, only a few of them mentioned sex, but only in very general and vague terms. One article published in 1933 claims that 'When dancing it is easy to become sexually aroused,'[14] while another article from the Dancing Daily (tiaowu ribao) writes about a certain cabaret, the MGM, that attracts 'sex-crazed' (semi) customers.[15] An article in the Entertainment Weekly (yule zhoubao) asserts: 'If a dancer is not popular, she must submit to the whims of lusty patrons. If she does not she will not earn enough money.'[16] In the mid-1930s, when the New Life Movement sponsored by the Nationalist government of China targeted dance halls as one of many 'vice industries' to be eradicated from Chinese society, there was plenty of discussion in the news media about the sexual allure of dance halls. For example, one article in the Crystal claimed that young women were being lured into the dance halls by the seduction of easy money, and that prostitution in these halls was common in an environment where women seduced men, particularly youthful students who should be studying instead of frequenting cabarets.[17] These were common complaints. Yet while it is apparent that sexual relations occurred frequently between men and women through the medium of the cabarets, there is very little evidence from newspapers and magazines of the era about what specific forms these seductions and erotic encounters took.

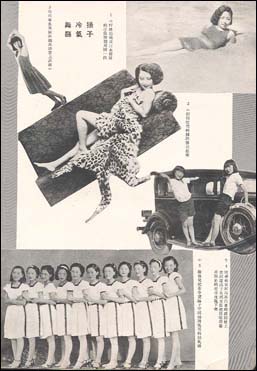

Figure 2. A page from the dance magazine, Dance Hall Special Writings (Wuchang Texie), 1938. Courtesy of Beijing Capital Library.

Figure 2. A page from the dance magazine, Dance Hall Special Writings (Wuchang Texie), 1938. Courtesy of Beijing Capital Library.

| |

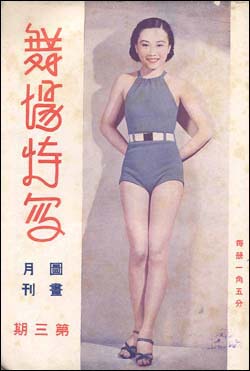

Figure 3. Front cover of Dance Hall Special Writings (Wuchang Texie), 1938. Dancers featured in these magazines often displayed their bodies and showed off their skin in revealing outfits, such as bathing suits. Courtesy of Beijing Capital Library.

Figure 3. Front cover of Dance Hall Special Writings (Wuchang Texie), 1938. Dancers featured in these magazines often displayed their bodies and showed off their skin in revealing outfits, such as bathing suits. Courtesy of Beijing Capital Library.

|

-

There was no precedence in Chinese urban culture for social dancing, and while men and women might seek certain forms of intimacy in the 'flowery world' of courtesan houses and teahouses that flourished in the city's foreign settlements, the women were invariably of the demimonde and not women of respectable households. So when commercial dance halls first arose in Shanghai in the 1920s, they were generally limited to the communities of foreigners who lived in the city or visited from abroad. Very few Chinese citizens set foot in these ballrooms initially, and therefore the Chinese imagination was set free to ponder what really went on behind closed doors as the loud foreign music blared and the dancing began. The Chinese novel Great Gate of Soul and Flesh (Ling Rou Da Men) published and circulated in the city between the late 1920s and early 1930s, provides a good example of how Chinese writers and readers may have imagined dance halls prior to their integration into the mainstream of Chinese urban culture.

Wu Nonghua's Great Gate of Soul and Flesh

-

In the early 1930s, in a campaign designed to clean up the city's media, the Shanghai Municipal Police collected a number of cases of pornographic Chinese literature in newspapers, magazines and bookstores. As was their policy, the police force had translators to translate Chinese texts into English. One text that appears in the SMP files in 1931 is The Great Gate of Soul and Flesh (Ling Rou Da Men), written by Wu Nonghua.[18] Police agents discovered this novel being sold in a Chinese bookstore in the International Settlement. Judging from the excerpts translated from Chinese into English in the police file, Ling Rou Da Men is a novel featuring several westerners who frequent dance halls, where they engage in collective sexual activities. There is no clear indication from these excerpts as to whether the story takes place in Shanghai or in a western metropolis such as Paris, London or Berlin. In the first passage translated by the police, a male character named Burteel takes a female character named Mary to the Derling Dancing Hall, which he tells her is really a 'great gate of soul and flesh.' Burteel gives Mary a 'passionate kiss' and continues his explanation: 'The men and the women who have come to this place are full of the "sparks of soul and flesh" and are moved by the force of self-combustion. They have come not for dancing but for extinguishing their "fire."' When Mary asks him if he has found a way to quench his own fire, Burteel replies that he has not and that this has caused him considerable suffering and halted his studies (apparently Burteel is a student). The narrator then explains,

The Derling Dancing Hall was well known for naked dances. These dances took place at midnight when the dancers took off all their clothing and pressed their 'flesh' tightly against one another. They did more than kissing and embracing. That night Miss Mary and Mr. Burteel did the same thing and they did not stop until dawn. Miss Mary was fatigued but she felt exceedingly comfortable throughout her whole body. This experience gave both of them a very deep impression.[19]

-

Later in the novel, Miss Mary, now fully initiated into the carnal rites of the dance hall, meets up with another man, Mr. Price. While in his hotel room, she shows him a nude photograph of herself, and then entices him to accompany her to the Victoria hotel. There they attend the hotel's cabaret, known as 'The Black Dance Hall.' In the Black Dance Hall, 'The men and women were naked and could do anything they pleased. They were also allowed to change their companions freely. The Hall was really a large sleeping bed.'[20] As the novel progresses, another male character, Laim, undergoes a similar experience, beginning in a bedroom and ending in a dance hall.[21]

-

All three passages share the same basic theme of the initiation rite, which takes place ultimately in the dance hall. Through some sort of enticement—a plea and explanation, a nude photograph, a striptease—a seasoned veteran coaxes a neophyte through successive levels of sexual experience, ending with an orgy that takes place in the darkened environment of the dance hall. Once the innocent is initiated, he or she is ready to pull others into the maelstrom of sensual passion that constitutes the dark world of the dance hall. This novel—so shocking that the Shanghai Municipal Police of the International Settlement took pains to ban it from selling in local bookstores—clearly played upon the imaginations of a Chinese audience, who may have wondered what westerners did behind closed doors. Frolicking naked in public spaces, freely exchanging partners, these fictional characters and their actions reflected both the fears and the fascination that western expatriates and their dance halls held on a gullible Chinese reading public during the 1920s, when very few Chinese had ventured into these establishments. It wasn't until the late 1920s that Chinese began to attend dance halls in significant numbers,[22] so such a novel may have sparked the imaginations of Chinese readers who equated dancing with sex.

-

Even more shocking is that these passages contain no moral component. Unlike traditional Chinese pornography, which is often masked in a stream of Buddhist apologetics, no sense of shame accompanies these actions. Instead, they are justified by the exigencies of the moment, by the pressing need to fulfill one's carnal desires. Westerners in this story use dance halls to quench the 'fires' of their lust, either with one or with multiple sexual partners. It is little wonder that the British-run Shanghai Municipal Police found this book particularly offensive as it made westerners seem like uncultivated beasts—but the passages from this novel suggest an emerging ideology of sexual freedom that condoned such behaviour for its ability to satiate 'natural' human desires. Nevertheless, the author employs several familiar tropes in order to make sense of the strange activities of the foreigners. For example, the discussion of lust held by the characters Mary and Burteel is carried out in a terminology that is strikingly Daoist. Here we see the author, Wu Nonghua, relating to his western fictional entities' desires and motives in his own cultural terms. Moreover, the relationship between Mary and Burteel brings to mind the 'Scholar and Beautiful Maiden' (caizi jiaren) motif common to traditional Chinese literature, in which a beautiful young woman helps a gifted but luckless student to achieve his scholarly goals. In this case, Mary does so by extinguishing the 'fire' of lust that prevents Burteel from concentrating on his studies. Thus, dance hall debauchery is described in terms familiar to the Chinese audience, and the strange and hidden world of the foreigners is, to an extent, localised. Ling Rou Da Men is a fantastical depiction of dance hall culture, and certainly there is no evidence that such rituals actually took place in dance halls in the city of Shanghai. Yet it could also be read in a metaphorical sense as an exaggerated depiction of the open and public sexuality of western dance hall culture for consumption by a society that equated western-style social dancing with sex.

Lei Zhusheng's Shanghai: A Living Hell

-

Other 'social novels' from the same period offer more realistic erotic portrayals of the dance hall demimonde. One example is Shanghai: A Living Hell (Haishang Huo Diyu, 1929) written by Lei Zhusheng.[23] This novel was published in Shanghai at least two years after dance halls had started to become popular among Chinese urbanites and the first wave of dance halls owned, operated and staffed by Chinese in the city had arisen. Dance hall culture was already part of the Chinese metropolitan experience, and this is certainly reflected in the realism and the details of the world of dance halls that the book recounts. As historian Mark Elvin argues, for Lei Zhusheng, the dance hall demimonde is an arena for the 'war of the bodily impulses against the constraints of convention, and the destruction caused by an insufficiently expert handling of their requirements.'[24] Xiao Feng (Little Phoenix) is a dance hostess who claims to have worked in a dance hall for three months, but to never have slept with a customer. She contrasts her own behavior with that of most other hostesses who have sexual relations with their clients in the hopes of having a long-term relationship and possibly even marriage with them, only to be abandoned 'like worn-out slippers with no heels' after these playboys have finished with them. Her customer Hua Yunsheng wishes to set her up in a private apartment, a precursor in Chinese urban society at the time to a long-term relationship and the institution of concubinage. Before agreeing to have sex with him, Little Phoenix first requests that he deposit a sum of money in a bank account in her name in case the relationship doesn't work out (often there was some sort of financial arrangement that went with such a relationship). Hua insists on having sex with her first and to trust that he will set up the account for her. Before their lovemaking session, Hua must first take off several layers of clothing on her body. She explains: 'Dance hostesses have to do so. The usual run of slippery rogues who pay to dance with me think they can have a bit of something from me, once they've paid their thirty cash [for a dance ticket]. They take advantage of the electric lights going out to stretch their hands out in utterly shameless fashion to my breasts, and feel about.'[25] Little Phoenix's comments suggest that erotic touching and feeling on the dance floor was a normal pattern of behaviour among dance hall patrons, but that hostesses had their own ways of defending themselves against unwanted explorations of their bodies. Hua Yunsheng does finally succeed in taking off her clothing and has his way with her, comparing her breasts to the Himalayas even though she counters that they are too small for such a comparison. However, the relationship quickly comes to an end after Hua angers a local gangster and flees the city like 'a kite without a string' leaving no trace of his whereabouts. After his departure and his failure to live up to his side of the bargain, Little Phoenix, lovesick and heartbroken, falls into a deep depression and is only saved by friends who buoy up her spirits. As Elvin argues, this peak into the sexual side of the dance hall demimonde suggests that 'sex is a delicious food but it is also demonic, dirty and enslaving.'[26]

-

While fictional, the story reflects real-life experiences in dance halls during a period when these establishments were first becoming part of the Chinese urban cultural experience in Shanghai. This story suggests that erotic adventures between patrons and hostesses were to be found both on the dance floor and in the private apartments of the city, but also that these sexual adventures or misadventures were fraught with the potential for misunderstandings and deceptions which could lead to pain and sorrow, particularly for the women involved. While these women might have been depicted as 'modern' and sexually free in one sense, they were still vulnerable to the excesses of male desire.

-

Other stories from the era depict these women as femme fatales, bent on 'preying' on young men of wealthy families and using their sexuality to gain status and wealth.[27] One example of such a story, also written during the same period, is Tears and Laughter of a Dancing Girl (Wuniang Tixiao Lu) published in Shanghai in 1928.[28] This novel follows the story of a young man named Xu Baoheng whose father is a magnate in the rubber industry. He pursues a dancing hostess named Li Yina with the intention of marrying her, though his parents are against the marriage proposal since she is from a poor family. After he pretends to go crazy to show his love for the girl, they relent, but they blame the hostess: 'Crazy or not he's certainly been to the dance hall again and smitten by that seductress.'[29] While the story is far from erotic or pornographic, it portrays another aspect of the dance hall demimonde and plays upon the fears of an older generation of wealthy Chinese who watched as their sons indulged themselves in this novel world of night-time entertainment and leisure and became ensnared by the wiles and charms of the city's dance hostesses.

Dancing with foreigners

-

Amongst the rich corpus of Chinese literature on Shanghai's dancing world including fictional portrayals as well as non-fictional articles in newspapers and magazines, the great bulk of this material focuses on social relations that occurred between Chinese dance hostesses and Chinese dance hall patrons. Seldom do we find cases written up in literature or the news media about Chinese hostesses having social or sexual relations with foreigners. Nevertheless there are enough sources to suggest that this did occur if rarely in the city's dancing world. Most of the literature on the city's nightlife written in the English language by westerners tends to focus on the relations that occurred between western men and White Russian hostesses cum prostitutes. There are even occasional mentions of Chinese men cavorting with Russian women, which initially proved shocking to the western community of the city when the first crop of Russian hostesses appeared in the early 1920s. Some even argued that this cross-racial fraternisation subverted the racial colonial order and threatened the lofty position of the 'white man' in China.[30] Similarly, there was a taboo in western colonial society in Shanghai that frowned upon sexual and certainly marital relations between white men and Chinese women. Yet arguably the dance hall culture of the city played a vital role in changing these racial biases and perceptions towards cross-cultural sexual relations by levelling the playing field, bringing westerners and Chinese in close contact both on and off the dance floors of the city.

-

By the 1930s, one does find occasional snippets of news items about Chinese hostesses and their foreign (western) male lovers. One such article describes a dancer named Chen Hailun (Helen Chen) who worked in a dance academy on Avenue Edward VII. In the article, the author writes about how she told him an interesting story of how she acquired the ability to speak foreign languages (English and French). When the dancer was working at the Ambassador ballroom (also on Avenue Edward VII), at that time her foreign language skills were minimal. One time a westerner requested to dance with her and engaged her in conversation, to which she could only reply "Yes, yes." Eventually the westerner requested her company outside the dance hall. In order to accommodate his request, the ballroom managers made her leave the ballroom out the back door. Apparently she had unwittingly agreed to a secret rendezvous with the westerner. After this incident, she was determined to learn foreign languages so as to avoid any future misunderstanding in her dealings with foreigners. Whether or not she engaged in any sexual relationship with the westerner is left out of the story, but it is implied that there was a sexual interest on the part of the foreigner, and that the interest was mutual, if only complicated by the language barrier between the two parties.[31] Another article from the Crystal published in the same year claims that 'Vienna dance star Sun Huiying (photo), 20 years old, started at Great Eastern, can speak English, so foreigners like to patronise her, foreigners and Chinese vie for her company.'[32] Yet another notes, 'Last spring Sun Huiying was the most notable dancer at the Great Eastern ballroom. Every evening a Western patron asked her to sit and spent dozens of dollars. Then suddenly she stopped dancing there. Some said she was living with the Westerner, some said she had another lover, at any rate we hear that she is now at Vienna dancing again, don't know if the Westerner still likes her.'[33] The article suggests that the love match between the Chinese dancer and her western patron was financially motivated (he spent lots of money on her in the dance hall) and that she may have been living with him. Also the tone of the article is neither one of surprise nor shock—so it must not have been too uncommon for western patrons to patronise and form social and sexual relationships with Chinese hostesses in the dancing world.

-

Nevertheless these sources only hint at sexual relations between Shanghai's cabaret hostesses and western patrons. The only source that I have found that deals explicitly with this topic is a memoir published by British journalist, Ralph Shaw. Written decades after the era in question, this memoir tells many erotic and pornographic stories about the author's experiences and adventures in Shanghai during the late 1930s. Shaw's memoir supports the notion that sexual relations that crossed the racial barrier were generally taboo in the British-American society of Shanghailanders who ran the city's International Settlement. In fact, the norms of British and American society in Shanghai and of Shanghailander society in general would have encouraged brief, furtive encounters between white men and Asian women, rather than the cultivation of longer and more involved relations.[34] Shaw recalls how Percy Finch, a leading American journalist in the city, warned him against the social consequences of close physical contact with Asian women:

Percy Finch, who was a staunch supporter of the Shanghai Club, often used to tell me that two Wongs never made a White. My predilection for oriental females had alarmed him and though he was no racial bigot he made it plain that lasting – and legal alliances with Chinese or Eurasian women could only result in a rapid descent down Shanghai's social ladder. 'If you fancy a bit of oriental tail, Ralph,' he would say, 'then follow the old empire-builder's dictum: "Screw 'em and leave em."'[35]

-

At the time that Shaw lived in the city in the late 1930s, Japan was at war with China and Japanese military forces had already occupied the outskirts of the city, leaving the foreign settlements under the jurisdiction of the westerners. Within the unstable and volatile context of the wartime era, Shanghai's nightlife industry was carried to greater heights of excess and decadence,[36] and Shaw's memoir is a valuable and unique if somewhat dubious record of the city and its night-time sex and entertainment industries. Oddly, while Shaw frequented the cabarets of the city, he appears not to have had any sort of ongoing relationship with Chinese cabaret hostesses. Instead his social and carnal relations as described in his memoir are with Japanese and Korean cabaret girls. In one episode, Shaw describes visiting a dance party organised by the Japanese military (at the time of the party he was still in the British Navy and was a representative of the British military) and being set up to dance with a Japanese hostess. While on the dance floor, though both are fully clothed, the dancer manipulates Shaw into having an orgasm by rubbing his erect penis with her own private parts, causing him to soil his pants in the process. It is tempting to read in this erotic encounter a statement about the growing power of Japanese imperialism in China and the waning of British power in the Shanghai region. Nevertheless the real importance of this passage lies in the bare eroticism of dancing itself and how it was—or certainly might have been—possible for two dance partners to have orgasmic sexual relations on a crowded dance floor. Shaw goes on to comment that different nationalities of women in these cabarets had different ways of reacting to male arousal. 'The Chinese girls, who could not expect an indecorous show of carnality by their own menfolk bred on the Confucian precept of modesty in all things, usually showed amusement at the instant and unmistakable sexual response of the white man.'[37] According to Shaw, while Chinese cabaret girls giggled and held their forefingers up in the air as a sign that their partners were aroused, Russian women were less likely to react and 'either coaxed it to greater degrees of sensual generosity or ignored it, depending on their response to the attractiveness of the patron.'[38] We do not have to take Shaw's taxonomy of racial responses to the male erection at face value, yet it is worth noting that as Shaw suggests, it was not uncommon for men to become sexually aroused and that dance hostesses must have had their own ways of dealing with this phenomenon when it occurred.

-

Yet, while arousal and even orgasm on the dance floor were likely a part of the cabaret scene—certainly a phenomenon that must have occurred with regularity in the cabarets that Shaw frequented on the margins of the settlements, if not in the high-class cabarets where a certain amount of decorum was expected—it was still in private quarters that sexual relations were carried out in full. Elsewhere in his memoir, Shaw discusses at length a relationship that he maintained with a Korean cabaret hostess named Anna.[39] As recounted in his memoir, Shaw was interested in Anna primarily as a sexual conquest and a playmate, and he did not envision a long-term relationship with her (nor apparently did she with him), although he respected her for her linguistic abilities—like many women who worked in the city's cabarets that catered to westerners, she could speak several languages passingly well. Shaw relates how the two had a short and intense social relationship, with Shaw taking her out to various establishments at night, but their sexual relations seem to have always been mediated through her work at the cabaret. Shaw did succeed in bedding Anna in her own private room in Joffre Terrace, though he claims that he did not fulfill her at first, since his excitement in seeing her nude for the first time in his private apartment gave him a premature ejaculation. Another encounter that Shaw has with Anna in his apartment ends up with her and a Chinese cabaret hostess named Lily having sex with each other by means of a dildo. Clearly Shaw revelled in the opportunities and possibilities of sexual adventure in Shanghai, including the possibility of watching two women have sex with each other, and he used the cabarets as a sexual zone for meeting and eventually 'conquering' cabaret girls. While Anna seems to have been more of a social companion or 'date' than a prostitute, other encounters of Shaw's are clearly based simply on a monetary exchange. In one passage, Shaw describes an encounter with three Korean hostesses of the Venus Cabaret, who brought him to their own apartment on Avenue Joffre in the French Concession. During this encounter, while Shaw had sexual intercourse with one of the Korean hostesses on her bed, the other two hostesses were having sex with each other on the adjoining bed, in full view (or at least in full earshot) of Shaw and his own sexual companion. Shaw claims that certain cabaret hostesses were adept at pleasing male customers with their sexual performances, and that they sometimes worked in teams to do so. It is not very useful to argue the 'truthfulness' of this and other of Shaw's descriptions of cabaret girls, since even if we accept his accounts as fact rather than fiction, without other corroborating sources we are left with a one-sided view of these encounters from the perspective of a British male adventurer. Nevertheless we can surmise that at its lower levels in areas such as the Trenches and Blood Alley, where foreign soldiers and sailors from many nations cavorted with an equally multi-national cast of hostess-cum-prostitutes, it was common for inter-racial sexual encounters to take place. While these encounters were certainly a product of 'asymmetric' relations between the West and East Asia, they are complicated by the agency of the women as well as by the rising power of the Japanese Empire, which was challenging western hegemony in Asia's colonial spheres. As Shaw suggests in his memoir, these sexual and social relations also helped to undermine the rigidity of colonialist attitudes towards the racial Other, whether that Other be Oriental or Occidental.

Conclusion

-

In the 1920s, cabaret culture streamed into Shanghai and became an integral part of the city's urban culture. This process began with westerners living in the two foreign concessions. As scraps from Wu Nonghua's novel Gate of Soul and Flesh suggest, the dance halls of 1920s Shanghai played a role in the Chinese imaginary as fantastical sites of orgiastic sexuality among foreigners. As cabaret culture became integrated into the fabric of Chinese urban culture in the late 1920s and 1930s, a new literature emerged both in the dailies and in the realm of fiction that covered these sites and followed the tangled relationships between Chinese men and women (and sometimes foreigners) who became involved in this world. As Lei Zhusheng's novel Shanghai: A Living Hell attests, cabaret hostesses were considered pitiful sexual playthings and objects of attraction and conquest by men who only later might abandon them. Yet another novel from the period, Tears and Laughter of a Dancing Girl, indicates that Shanghai's Chinese high society also considered cabaret hostesses to be cunning and wily women bent on ensnaring their wealthy sons into unwanted marriages and entanglements. Clearly the cabaret was an important space of sexual conquest, negotiation, and exploration in the collective imagination. Finally, Ralph Shaw's memoir constructs the city's cabaret culture and the city in general as a ribald sexual fantasy world where women and men from different cultural and racial backgrounds could indeed achieve orgasmic pleasures and delights both on and off the dance floor. With its dance floor where people could try out the new popular dances streaming in from the western world, the cabaret in 1920s–1930s Shanghai proved to be a powerful sexual contact zone, a fantasy space for border and boundary crossing, allowing people of different class, occupational, national and ethnic backgrounds to experiment with, explore, and expand their sexual experiences and identities both in fiction and in reality.

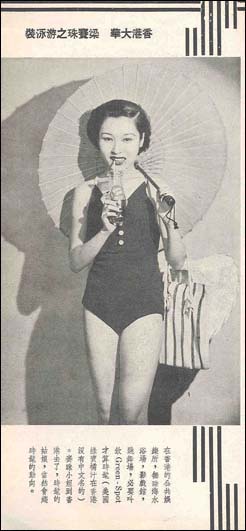

Figure 4. Dance star, Liang Saizhen, in Wusheng (Dance wind) 1938. Courtesy of the Beijing Capital Library.

Figure 4. Dance star, Liang Saizhen, in Wusheng (Dance wind) 1938. Courtesy of the Beijing Capital Library.

| |

Figure 5. Dance star, Liang Saizhen, in Wusheng (Dance wind) 1938. Courtesy of the Beijing Capital Library.

Figure 5. Dance star, Liang Saizhen, in Wusheng (Dance wind) 1938. Courtesy of the Beijing Capital Library.

|

Endnotes

[1] Shanghai was undisputedly the centre of the Chinese Jazz Age, which scholars acknowledge to have occurred through the 1920s and 1930s, when jazz and its associated entertainment cultures were introduced to and flourished in the metropolis. The two major studies of Chinese Jazz Age entertainment culture are Andrew Jones, Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001; and Andrew David Field, Shanghai's Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919–1954, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010.

[2] For a broader study of representations of 1930s Shanghai cabaret hostesses in film and print, see Andrew Field, 'Selling souls in sin city,' in Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922–1943, ed. Zhang Yingjin, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1999, pp. 99–127.

[3] Elsewhere I and others have discussed how the avant-garde writer Mu Shiying's fictional portrayals of the city's cabaret culture in the 1930s were key texts in the imaginary construction of metropolitan life in Jazz Age Shanghai. See Andrew Field, 'Selling souls in sin city,' and the introduction to Shanghai's Dancing World. See also Leo Ou-fan Lee, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

[4] Lewis Erenberg argues that nightlife contributed substantially to changes in social and sexual mores that brought America out of the Victorian Age and into the Jazz Age. See Lewis Erenberg, Steppin' Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. These changes took place between the 1890s and 1920s. Kathy Piess argues that dancehalls in early twentieth-century New York were spaces where young women and men (teenagers in our parlance) sought out sexual and erotic encounters with each other and that these were vital spaces for the courtship rituals for thousands of young immigrants living in the great metropolis. See Kathy Piess, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn of the Century New York, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986, chapter 4. Randy McBee also argues that dancehall culture helped to change gender and social relations and helped women to negotiate new and more sexually permissive relations with men that went against the mores of their parents. See Randy McBee, Dance Hall Days: Intimacy and Leisure among Working-Class Immigrants in the United States, New York: New York University Press, 2000.

[5] While studies of treaty port Shanghai abound, perhaps the best study of the privileges and powers granted to westerners in Shanghai during this era is Nicholas Clifford, Spoilt Children of Empire: Westerners in Shanghai and the Chinese Revolution of the 1920s, Hanover NH: University Press of New England, 1991.

[6] Shanghai's sex industry has received ample coverage by scholars in recent decades. At least three major monographs have been published on the prostitution culture and industry of late Qing and Republican Shanghai. These include Christian Henriot, Prostitution and Sexuality in Shanghai: A Social History, 1849–1949, trans., Nõel Caslelino, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001;Gail Hershatter, Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution and Modernity in Twentieth-Century Shanghai, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997; and Catherine Yeh, Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals, and Entertainment Culture, (1850–1910), Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

[7] The first and only major sociological study of taxi-dance halls in America examined Chicago around 1930. See Paul Goalby Cressey, The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. Information about the importance of taxi-dance halls in American cities as zones of sexual contact between different races and classes of people, particularly in the case of Filipino men and white American women, can be found in Kevin J. Mumford, Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997; Linda Espana-Maram, Creating Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila: Working Class Filipinos and Popular Culture, 1920s–1950s, New York: Columbia University Press, 2006; Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns, '"Splendid dancing": Filipino "exceptionalism" in taxi dancehalls,' in Dance Research Journal, vol. 40, no. 2 (Winter 2008):23–40.

[8] For a definition of the term 'transculturation,' see Mary Louise Pratt, 'Arts of the contact zone,' in Profession, vol. 91 (1991):33–40, p. 34.

[9] See E. Taylor Atkins, Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan, Durham: Duke University Press, 2001, Chapter 2.

[10] See Field, Shanghai's Dancing World, Chapters 7–8 for a discussion of how the Nationalist government attempted to regulate and ban the city's dance hall industry.

[11] Field, Shanghai's Dancing World, especially Chapter 6.

[12] A special magazine printed by the establishment shows blueprints and photos of the Paradise Ballroom of the Sun Company Department Store including photos of its dance hostesses, managers and male staff. See Pan Yihua (ed.), Daxin wuting kaimu jinian tekan (Paradise ballroom opening memorial special publication), Shanghai: Daxin gongsi, 1936.

[13] Shanghai wuxing zhaoxiang ji (a collection of photographs of Shanghai dance stars), Shanghai, 1939, p. 94.

[14] Jingbao, 13 July 1933.

[15] Tiaowu ribao, January 19, 1941.

[16] Yule zhoubao, October 12, 1935.

[17] Jingbao, 1 July 1934.

[18] Extracts of several pages from Lingrou damen appear in English translation in the Shanghai Municipal Police Files, D-2344. Publishing date unknown.

[19] Lingrou damen, pp. 82–91.

[20] Lingrou damen, pp. 149–55.

[21] Lingrou damen, pp. 174–76, 178.

[22] See Field, Shanghai's Dancing World, Chapter 2 for a discussion of the first wave of Chinese dance hall patronage and culture in Shanghai in the years 1928–1931.

[23] Mark Elvin translates passages from and discusses this novel in the context of an article analysing Chinese notions of mind and body in 'Tales of Shen and Xin: body-person and heart-mind in China during the last 150 years,' in Zone 4, Fragments for a History of the Human Body, part. 2 (1989):267–349.

[24] Elvin, 'Tales of Shen and Xin,' p. 303.

[25] Elvin, 'Tales of Shen and Xin,' p. 306.

[26] Elvin, 'Tales of Shen and Xin,' p. 311.

[27] Field, in 'Selling souls in sin city,' discusses the various ways in which dance hall hostesses were portrayed by the city's media in the 1930s.

[28] Wang Yongkang, Wuniang tixiao lu, Shanghai: Huadong Shuju, 1928.

[29] Wang Yongkang, Wuniang tixiao lu, p. 43.

[30] See Field, Shanghai's Dancing World, chapter 1 for a discussion of White Russian hostesses and the controversy that they generated in the settlements in the early 1920s.

[31] Jingbao, 3 November 1935.

[32] Jingbao, 21 November 1935.

[33] Jingbao, 10 November 1935.

[34] Herbert Lamson, 'Sino-American miscegenation in Shanghai,' in Social Forces, vol. 4 (1936):573–81. For accounts of racist colonial attitudes of white Europeans towards Chinese and Asians in the semi-colonial context of Shanghai, see also Nicholas Clifford, Spoilt Children of Empire; Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai, Columbia University Press, 2003; and Harriet Sergeant, Shanghai, London: John Murray Publishers, 1999.

[35] Ralph Shaw, Sin City, New York: Time Warner Paperbacks, 1992, p. 140.

[36] See Field, Shanghai's Dancing World, Chapter 6.

[37] Shaw, Sin City, p. 71.

[38] Shaw, Sin City, p. 71.

[39] The story of Anna appears on pages 82–92 of Shaw's memoir.

|