'Dissolution of Marriage':

Gender, State and Islam in Contemporary Bugis Society

in South Sulawesi, Indonesia[1]

Nurul Ilmi Idrus

Introduction: divorce and tensions between Islam, the state and local practice

-

In the 1974 Indonesian Marriage Law, a divorce can only be granted through the Religious Court which must first try to reconcile the husband and wife. A Hadith states that 'divorce is lawful, but deeply despised by Allah.'[2] Common advice from the judge in the Religious Court is: 'If you can't carry it in your hand, carry it on your shoulder. If you can't carry it on your shoulder, carry it above your head.'[3] However, even though it is shameful, especially for women, the number of divorces is increasing, and the number initiated by women is relatively higher than that for men in Indonesia. This paper examines how Bugis beliefs and practice, the Marriage Law and the Religious Courts shape the patterns of marital dissolution in contemporary Bugis society.

-

For Indonesia's Muslims, marriage and divorce are contractual matters regulated by their religion, but the Indonesian Marriage Law (Chapter VIII: article 38) codifies these practices.[4] Divorce is the focus of discussion here. While marriage is viewed as a 'legal contract,' divorce is regarded as 'breaking the marriage contract.'[5] There are three grounds which may legally discontinue a marriage: death, divorce and decision of the court, and in the case of divorce for Muslims, this is the Religious Court, or Pengadilan Agama.[6]

Indonesian Marriage Law (Chapter VIII: article 38)

-

In Islamic law, divorce is severance of the marriage bond and is allowed because marriage is regarded as a contract which can be broken by either one or both parties. However, one cannot divorce without a legitimate reason.[7] Islam teaches that, as with marriage, one has to divorce lawfully. The husband is the one who pronounces the talak (A. divorce). A Hadith (story of the life of the prophet) states 'any woman who asks for divorce without a reason, the smell of heaven is forbidden for her.'[8] The 1974 Indonesian Marriage Law indicates that the husband must have good reason to pronounce the talak, and a divorce can only be granted through a Religious Court (Pengadilan Agama) after the husband and wife have tried to reconcile.[9] This reflects the position stated in a Hadith that 'divorce is lawful, but deeply despised by Allah.'[10] Therefore, the Indonesian legal system encodes the principle that divorce should be avoided if there is still a way to work out the marriage.

A Court hearing in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap

-

This paper reports on the practice of divorce in a specific local context, the district of Sidrap in the province of South Sulawesi, inhabited by Bugis-speaking peoples. In Sidrap, the majority of the population (93.39 per cent in 2009) are Muslims (Sidenreng Rappang in Figures 2010),[11] and local norms significantly influence the operation of the legal system, how people deal with marriage, divorce and reconciliation. For the Bugis people of Sidrap the term for divorce is sipurang,[12] which carries the meaning of terminating (pura). Thus sipurang means terminating the marriage. Either spouse may request a divorce; which is known as cerai gugat when the divorce is demanded by the wife and cerai talak when the request comes from the husband. For the Bugis, both are shameful occurrences.[13]

-

For the Bugis, sipurang is a tabooed word (B. pémmali).[14] If a husband or a wife states, 'I do not want to see your back' (dé'na uélo mitai pungku'mu) because the partner is reluctant to see her/his back (pungku'), not to mention her/his face; or 'return to your parents' (I. pulanglah ke rumah orang tuamu) since the partner does not want to see her/him. Such statements are already considered as belonging to the 'language of divorce' (I. bahasa cerai). Regardless of the legality, she/he has been customarily divorced (ritelle' ade') given that it has been pronounced. Despite the fact that women can divorce their husbands, when the judges talk about divorce, instead of using the genderless term—cerai—they used the term talak, which is the term for divorce initiated by the husband. To me, this implies an assumption that it is the husband who is entitled to divorce his wife rather than the reverse.

-

In the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap, when the judges deal with cases of divorce in the court hearings, they commonly give the following advice when they try to mediate the problems in couples' marriages:

If you can't carry it in your hand, carry it on your shoulder.

If you can't carry it on your shoulder, carry it above your head.

Nakko dé'mullé wiccangngi, lémpa'i.

Nakko dé'mullé' lémpa'i, jujungngi.[15]

-

Analysing this piece of advice, wiccang (B. carrying) refers to 'lower' (hand), lémpa' (carrying on shoulder) refers to 'middle' (shoulder), and jujung (carrying above your head) refers to 'upper' (head). It thus begins with the easiest way to carry, wiccang; then moves to the more difficult, lémpa'; and ends with the most difficult, jujung. This advice does not just delineate the steps to follow, but also reflects the problem-solving methods of handling marital problems in Bugis, which make reference to the teachings in the indigenous textual tradition, lontara'. If the application of this wisdom cannot solve the problem, then the marriage will end with divorce (sipurang).[16]

-

The advice describes how one should handle problems in marriage in stages, by carrying in the hand (mawwiccang), on the shoulder (mallémpa') and on the head (majjujung), indicates that one should stay in a marriage, as patiently as possible, no matter what the problems are. Although such advice can be directed at both husband and wife, I observed in a number of court hearings that such advice is usually given to the wife, especially when the husband apologised for his behaviour. Nevertheless, such efforts might raise questions such as how can a woman stay in a marriage when her life is in danger? Should the cultural considerations be so significant that a woman should not leave her house even when her life is at risk?[17]

-

The Bugis consider divorce to be shameful, not only for women, but also for men. This is not the case in all of the Muslim people of the archipelago: see for example discussion of divorce among the Sundanese of west Java.[18] However, the stigma is greater for women, especially if a woman is divorced by her husband because of his infidelity, not to mention her infidelity. The infidelity of the husband may lead to gossip which pushes a woman into a corner, since it is assumed that such a wife did not 'serve' her husband properly, expressed in Bugis and usually uttered by elders as 'she is not capable of meeting her husband's needs' (B. dé'na issengngi duppaiwi élo'na oroanéna). In general, the advice given by the judges in court hearings sided with the men. A man was asked to compromise only if he still wanted to reconcile the marriage, regardless of the reasons for divorce, by persuading his wife to withdraw from the case. The following case study, of Tikka's divorce, exemplifies the complex interaction of law, religion and custom in cases brought to the Religious Court in Sidrap

Case Study 1 – Tikka

-

Tikka was a victim of domestic violence throughout her marriage. I met her when I observed her court hearing in 2000. She had married Kadere in 1975, and had lived separately from him since March 1999. Tikka had finally left her husband (leaving her children in the family home) when she could no longer tolerate his abusive behaviour. She had been hit until she bled and was hospitalised. Since this separation, Kadere had been having an extramarital relationship with another woman and had never let Tikka see their children.

Figure 1. A Court Hearing in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap. Photographed by Nurul Ilmi Idrus, 2000.

Figure 1. A Court Hearing in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap. Photographed by Nurul Ilmi Idrus, 2000.

|

-

Despite the fact that the cruel treatment experienced by Tikka was reasonable grounds for divorce based on the 1974 Marriage Law,[19] Tikka was criticised by the judges because she had left the house (nasalai bolaé). In Bugis culture, it is tabooed by elders (nappémmaliangngi tomatoaé) for a wife to leave the house during a marriage dispute. This is considered similar to slapping her husband's face in public since it is seen as violating her husband's authority, regardless of the reason for her departure. Using an analogy of a human body, the husband is regarded as the head and the wife is the body. The body without a head is blind and a head falls over without the body. Husband without wife or vice-versa, will unbalance family life, as husband and wife are considered to be 'two-in-one.' In fact, Kadere had often left the house when they had marital disputes. In regard to marriage disputes, a piece of advice frequently uttered by elders to young couples is:

If for any reason you or both of you get angry with each other, do not ever leave the house because such behaviour is tabooed by elders.

Nakko engka saba'-saba' namumacai ri lakkaimmu, iaré'ga musicairi, aja' lalo musalai bolamu, nasaba' iaro gaué, nappémmaliangngi tomatoaé.

-

The above statement is directed at both husband and wife, but this advice is, in fact, usually given to wives. Indeed, the advice aims to prevent outside interference as well as indicating the couple should be capable of solving the problem as a private matter. Tikka stated:

I had been married for over 24 years and I had experienced violence since the early phase of our marriage. My husband was a violent man. He liked to utter bad words to me as well as hit me. Whenever he got angry, I was the one to be blamed. He was not just angry (B. maréso macai'), but also a batterer (paccalla-calla). He said I was a misfortune, a worthless wife, stupid and many other words directed at me and he would spend the nights in someone else's house. I felt my life with him was useless, except for my children. Whatever I did he never appreciated it. Finally, he hit me on the head and I was bleeding, I was taken to the hospital by my neighbour and my head had to be stitched. I thought I was going to die. After that we separated. What made me really sad was that he took all the children and did not allow them to see me or me to see them. Then, I tried to negotiate with him by asking him to work out our marriage. But he came to me and hit me again.[20]

-

The attitude of judges in the Pengadilan Agama in dealing with violence against women in conjugal relations seemed to be ambivalent. Although violence in marriage was addressed in Tikka's case, the consideration of custom (adat) surrounding conduct during disputes became critical in the process of the court hearing. Tikka was criticised by both the judges and her husband during the court hearing. The judges asked, 'Why did you leave your husband when you were angry?' (B. Magi muwélai lakkaimmu riwettu macai'mu?). 'I was chased away,' she said. Violence in the home, on the other hand, was the formal stated reason. Tikka and Kadere finally divorced in the middle of 2000 after twenty-four years of marriage, including one year of separation (B. mallawangeng).

-

In 1949, Barend ter Haar pointed out that separation before granting a divorce was common in Indonesia.[21] This was still evident in a number of court cases that I observed. Separation in Bugis is encouraged to give the couple time to have second thoughts about whether they want to continue with the divorce or to reconcile the marriage. Nakamura, in a study of divorce in Kotagede, Central Java suggested that separation is also designed to discontinue sexual intercourse and thus avoid pregnancy preceding the divorce based on Islamic law.[22] During the separation period and after the divorce, Tikka lived with her parents, and her children—one of them who was married and had a child—lived in the house where Tikka and her husband used to live together, while her husband lived with his family. Since Tikka had had an arranged marriage, the psychological burden to return to her parents because of divorce was insignificant, as her family still welcomed her. It is common in an arranged marriage that any subsequent marriage break-up becomes, to a great extent, the parents' responsibility. If Tikka's marriage had been by free-choice, the consequence might have been different.[23]

Case Study 2: Ibu Kasmawati and Pak Yunus: a case of polygamy?

-

Ibu Kasmawati and her husband Pak Yunus were teachers in a local school. They filed for divorce in the Religious Court but only a few weeks after the first stage of divorce (A. talak 1) (see below) was granted, Pak Yunus remarried another woman. According to the Marriage Law, only a wife has to wait for the waiting period (iddah) after the divorce.[24] On the grounds of this, Pak Yunus could marry during the iddah of Ibu Kasmawati or choose to return to her before the end of her iddah.

-

Talak, or divorce, has three steps, which aim to prevent arbitrary divorce since a couple may still be reunited before coming to the final stage (talak 3: talak ba'in). As stated in the Qur'an (Al-Baqarah: 229), a divorce is only permissible twice: after that, the parties should either hold together on equitable terms, or separate with kindness. If talak ba'in has already been granted, a wife has to marry another man, then get a divorce after that marriage is consummated (A. ba'da dukhul) and pass her iddah,[25] if she wishes to remarry her original spouse. Each of them, however, cannot marry someone else for the purpose of remarrying his/her original spouse.

-

However, a few days before Ibu Kasmawati's waiting period (iddah) ended, during a school camp his male and female colleagues urged Pak Yunus to 'take his portion' (B. malai tawana), which carries the sense in English of sexual intercourse. Ibu Kasmawati was intentionally left alone in a tent by her female colleagues, while male teachers provoked her husband to approach her. This 'meeting' finally ended in their making love, confirmed by a female colleague the following day. The 'drama' was designed to be an expression of the Bugis feeling of social solidarity (pessé) among teachers, who pitied Ibu Kasmawati given that she still expected her husband back. It was understood that through this plan they would be able to reunite without remarrying, given that a husband and a wife may still return as a married couple if they happen to change their minds before the wife has passed her iddah, that is, three menstrual periods, according to the Islamic Law.[26] However, can the incident of sexual intercourse be accepted as a mutually consensual reconciliation (silisuang)?[27] Kompilasi Hukum Islam (KHI, Compilation of Islamic Law) (Chapter XVIII:165) states that reconciliation (I. rujuk) without the wife's consent can be regarded as illegal by the Religious Court.

-

Given that there was no complaint from Ibu Kasmawati, her silence was seen as indicating her agreement. As the Qur'an states in Al-Baqarah:231, a husband may divorce his wife as well as reconcile with her before the end of her iddah. It was assumed that because Pak Yunus had got his 'portion' (B. purani naala tawana) before the end of Ibu Kasmawati's iddah period, he was still her husband. In other words, he had given his original wife a co-wife (mappammarué). Nevertheless, he spent most of his time with his second wife.

-

In contrast, Ibu Kasmawati never accepted that she had been given a co-wife (ripammarué, passive verb of mappammarué), as shown by the fact that she would never let Pak Yunus spend the night in her house to avoid being ripammarué. Hence, there are different perceptions of mappammarué between Pak Yunus and Ibu Kasmawati. Since the sexual intercourse before the end of Ibu Kasmawati's iddah period was regarded as reconciliation (silisuang), Ibu Kasmawati was still his legal wife as far as Pak Yunus was concerned. On the other hand, not staying or spending the nights with Ibu Kasmawati indicated that she did not consider full reconciliation to have occurred. She seemed ambivalent in view of the fact that they had had sexual intercourse, both in the tent and on several occasions in her house during the day. She insisted that in order to be reunited as a couple, however, Pak Yunus had to divorce his second wife and to perform a remedial marriage (B. kawing pabbura; I. kawin obat). According to Bugis custom (adat), a remedial marriage is a ceremony of reconciliation to re-establish a couple as married after the first or second stage of divorce (A. talak raj'i), or for those who have a shaky marriage, in order to recuperate from any marriage disputes.

-

Pak Yunus liked to talk about his second wife's positive points, such as 'she always accompanies me when I am eating or watching TV, and welcomes me home from work' to compare her with Ibu Kasmawati. This led to gossip about Ibu Kasmawati's 'negative behaviour' towards her husband. People said: 'She does not know how to fulfil her husband's needs' (B. Dé'na issengngi moloi élo'na lakkainna). The violence experienced by Ibu Kasmawati was no longer a hot issue, as it had been when they were still a married couple (sikalaibiné) and about to divorce. However, I was told by a female colleague of Ibu Kasmawati, that she felt Pak Yunus was trying to justify the situation in his former marriage, so he would not shoulder all the blame and could still enjoy his polygamous situation.

-

The legal situation in this case not only had reference to the Marriage Law but also to a special regulation further restricting rights to polygamous marriage for civil servants. State Regulation (Peraturan Pemerintah) No.10/1983 (article 4), hereafter PP 10/1983, determines that a male civil servant should have the permission of his superior before divorcing his wife or acquiring another. In many instances, this 'regulation' is ignored. Ibu Kasmawati and Pak Yunus, were both school teachers in the same government school. Officially, Ibu Kasmawati could file for divorce because of her husband's infidelity and violence. Under PP10/1983, she was entitled to submit a complaint through her husband's superior. In practice, the complaint begins through the head of the official women's organisations, Dharma Wanita or PKK at the village level,[28] in this case, the wife of the principal of the school where Ibu Kasmawati and her husband both worked as teachers. However, since the principal, Pak Bakri, had also had an extramarital relationship, followed by the fact that he was practising illegal polygamy[29] (through illegal marriage or kawin liar),[30] such a complaint seemed pointless. Another female teacher in the same school criticised the principal's attitude, asking how a superior could reprimand his staff if he himself practiced polygamous marriage and remarried without his first wife's consent? One could not admonish others if one played a similar game in one's own marriage. Despite the fact that polygamy for civil servants is restricted,[31] this case was considered to be 'mutual agreement' (I. tahu sama tahu) between Pak Yunus and his superior, Pak Bakri, in a mutually advantageous (illegal) deal with the plausible excuse that 'his wife did not complain about her husband's second marriage.' Such argument is logical to some extent, but it encourages others to continue to manipulate the regulations.[32]

-

According to Suryakusuma,[33] PP No.10/1983 was supposed to protect civil servants' wives from polygamy and divorce, but it has rebounded on them. This led the former Minister of Women's Empowerment, Khofifah Indar Parawangsa, to question the usefulness and the continuity of PP No.10/1983, as it has not prevented the occurrence of adultery and polygamy. While rumours regarding the revocation of PP No.10/1983 have created anxiety among some wives of civil servants, others may not be concerned. For example, some commented that adultery and polygamy would worsen if the PP No.10/1983 were revoked. Others argued that the PP No.10/1983 has no power to control the sexual and marital life of civil servants, as many high government officials were and are involved in adultery as well as polygamy without adverse consequences.[34]

Divorce registration

-

I now return to the subject of divorce registration. In Sidrap as well as in Makassar the records divide divorce registration into two categories: cerai gugat (wife-initiated divorce) and cerai talak (husband-initiated divorce).[35] However, there is no category to indicate the mutual initiation of both husband and wife to file for divorce. In fact, I found during the court hearings that when both parties wanted to get a divorce, the registration was typically initiated by the husband. Hence, it was categorised as cerai talak. In such a case, the husband is identified as the plaintiff (I. penggugat) and the wife become the accused (tergugat) in the official report.

-

In Sidrap, the record of the initiation of a divorce is associated with the one who pays for the divorce. All cases of cerai gugat were paid by women, unless there had been prior agreement that the husband would pay the divorce costs before registering the case in the court. Such an agreement usually occurred if the man was eager to get divorced quickly. In other cases, wives had to live with an uncertain status (status tergantung) until they could afford to pay the divorce costs, especially women without their own incomes. In contrast, the cost of cases of cerai talak was automatically paid by men.

-

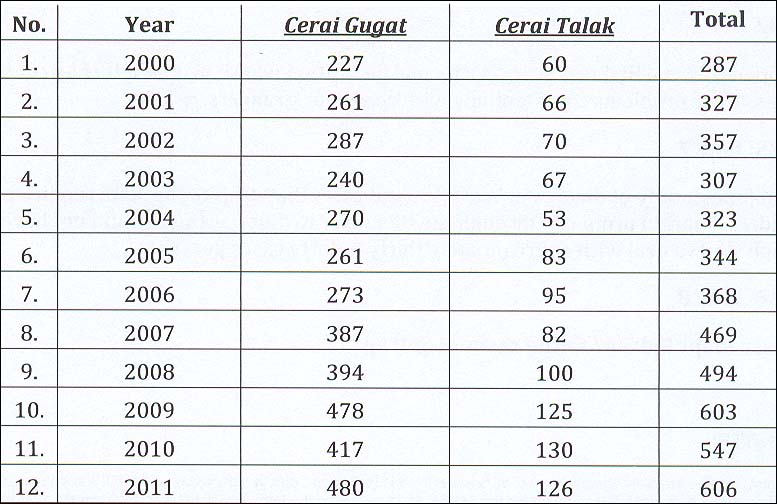

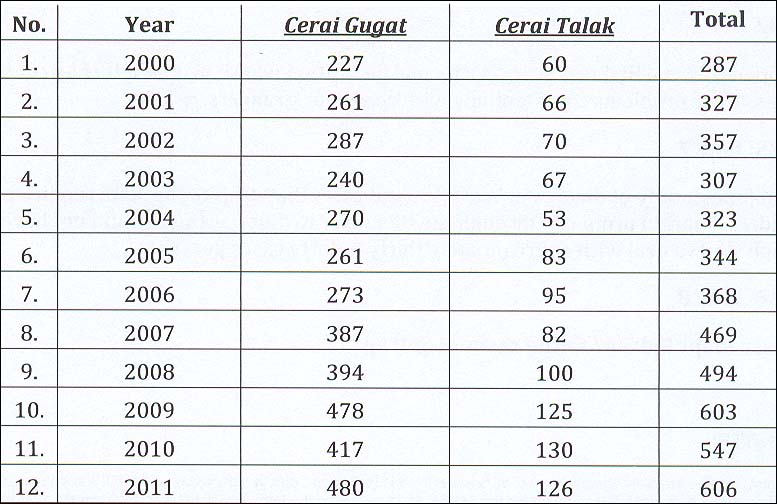

Data provided by the Pengadilan Agama in Sidrap indicates that the number of cases of cerai gugat was much higher than the number of cases of cerai talak,[36] as can be seen in the following table:

Table 1. The number of cerai gugat and cerai talak, 2000–2011.

Calculated from documented cases in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap (2012).

-

This higher number of women demanding divorce (cerai gugat) leads one to assume that more women suffer in marriage and that their suffering is more severe. It may also reflect that divorce can be less important for men because they also have the option of polygamy which women do not have. This figure indicates that the primary clients of the courts were women. Even before the existence of the Marriage Law of 1974, Lev has shown similar findings.[37] However, a study of divorce in West Java indicates that there is a number of ways wives can obtain divorce. Rather than simply initiating a divorce, one way for a wife to obtain a divorce is by persuading her husband to pronounce the talak. In this sense, the case is registered as a husband-initiated divorce.[38] This method was also noted in Nakamura's study of dissolution of marriage in Kotagede, Yogyakarta.[39]

-

Grounds for divorce, in this sense, refer to the reasons for legal divorce requested through the Pengadilan Agama. However, my observations of court proceedings and interviews with petitioners provide further information. The reasons cited in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap were economic problems (I. masalah ekonomi), moral crisis (krisis moral), usually indicating male infidelity,[40] irresponsibility (tidak ada tanggungjawab), fertility problems (masalah biologis), interference by a third party (gangguan pihak ketiga), polygamy (dimadu), jealousy (cemburu), incompatibility (tidak ada kecocokan), usually implying tension between the couple or conflict between affinal relatives, physical abuse (penganiayaan), forced marriage (kawin paksa), political problems (masalah politik), and conviction of a crime (dipenjara). Indeed, incompatibility was the dominant reason for divorce in Sidrap, followed by irresponsibility. Wife-beating and forced marriage are also among dominant reasons for divorce.

-

Nakamura claims that irresponsibility leading to unhappiness is the most common reason for divorce stated in the court reports.[41] Forced marriage and beating were not mentioned by Nakamura which might be because these reasons were not relevant in Kotagede, or because they were included under 'other', or, alternatively, the appropriate questions were not asked. Hildred Geertz concluded in her findings of Modjokuto that divorce was largely a result of abbreviated courtship, economic irresponsibility, conflict between affinal relatives and arranged marriages.[42] Even though my interviews with the judges in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap indicate that conflict between affinal relatives is in many cases a cause of marriage disputes, it is not registered as one of the reasons for divorce, but such cases are included under incompatibility. In line with this, my male and female informants in Sidrap told me that the most common reasons for divorce were irresponsibility (which meant that the husband had neglected to provide adequate living necessities to his wife and children—usually because of leaving the village in search of fortune (B. massompe')), and infidelity related to polygamy, not to mention kawin liar.

-

Susan Millar found in Soppeng, another Bugis district in South Sulawesi, that the dominant reason for divorce listed in the Pengadilan Agama was failure to satisfy the obligations of the contract.[43] This ground is similar to incompatibility either between the couple or between their families. The 'irresponsibility' or 'incompatibility' grounds for divorce are interrelated. A husband's failure to satisfy the obligations of a marriage contract leads to tension and unhappiness between the couple. When such a case is filed, it is registered under incompatibility by the divorce registrar in the Pengadilan Agama.

Counselling processes and reconciliation

-

The 1974 Marriage Law requires the Religious courts to attempt reconciliation of the parties, and this is formally done through the BP4 (Badan Penasihat Perkawinan, Perselisahan dan Perceraian, Body for Marriage Disputes and Divorce Counselling) attached to the Pengadilan Agama.[44] BP4 is attached to the Balai Nikah (balai means place, nikah means legalisation of marriage)[45] the local office which registers marriages and gives information and advice to Muslims who are planning to marry (B. kawing), but also to those considering divorce (sipurang) or reconciliation (silisuang). My Sidrap informants were more familiar with the term Balai Nikah than BP4. For people in the village, Balai Nikah was only known as an office for marriage registration: no one understood that this institution could also provide marriage counselling. Marriage disputes were either solved internally within the family and/or couples directly filed for divorce at the Pengadilan Agama. As people did not seek divorce at BP4, no one filed for divorce through the Balai Nikah. Thus, the Pengadilan Agama was also involved in marriage counselling. No matter who initiated the divorce, the marriage counselling or advising took place during the court hearing, usually in the first court sitting when husband and wife were present at the same time. One case hearing usually consisted of at least three court sittings.[46]

-

In Sidrap, regardless of who initiates the divorce, whatever the reasons for divorce, and whether or not the husband agrees to divorce, all cases are brought to the Pengadilan Agama. Balai Nikah did not function as it did in Kotagede where Nakamura conducted her research. This might be because the role of the Balai Nikah was not widely known in Sidrap and people seemed to be ignorant of how it could be used for divorce (B. sipurang) and reconciliation (silisuang). According to the judges, when a case turned from divorce (sipurang) to reconciliation (silisuang) without the intervention of the court, the case became uncertain (I. tergantung), which meant that the couples did not report reconciliation cases to the court. Information regarding reconciliation was later found from people talking about the delicate reconciliation of the couple. This reconciliation might be because of the intervention of the family or solely between the couples themselves, and such an event might easily become widely known, as one person's business easily becomes everybody's business in the village as well as in the regency. However, there are also rare cases in which the couple or the husband or the wife come to the court and ask to terminate the case because they have already reconciled the marriage. In such circumstances, the case is closed on demand by either the husband or the wife or both. But even though the court in Sidrap endeavoured to provide counselling and reconciliation, the people saw it mainly as a place for divorce. Every time I wanted to visit the Pengadilan Agama, Ibu Bakri (my hostess) said: 'Ibu Ilmi is going to the place of divorce.' Local mini bus (pete'-pete') drivers always greeted me: 'Are you going to deal with the divorce people again, Ibu Ilmi?' The tricycle driver (I. tukang beca) in Pangkajene once asked me: 'Are you going to divorce?' because he had seen me visiting the Pengadilan Agama several times.[47]

-

In contrast, in the city of Makassar, although not all people who experienced marriage disputes sought advice at the BP4,[48] it was used as one marriage counselling alternative by the urban community. Nevertheless, there were also cases in which people came directly to the Pengadilan Agama to register a divorce. In such case, the Pengadilan Agama acted as the BP4. What was considered best procedure by the state was not always ideal in the eyes of the community.[49] In the words of my informants, seeking advice at the BP4 was more likely to complicate the problem because, for instance, men were reluctant to come for marriage counselling because they considered themselves shamed (B. ripakasiri') by discussing their marriage problems with outsiders.[50] It was too public for what was considered a private matter. On top of this, the BP4 was seen as a formal institution where people felt they could not express their problems confidentially with complete strangers.[51]

-

The situation is quite different in the province of West Java, where a divorce can be officially registered only after counselling is implemented through the BP4.[52] This is similar to Nakamura's finding that people in Kotagede (Yogyakarta) usually proceeded to the BP4 for marriage counselling before coming to the Pengadilan Agama.[53] In Sidrap, it was considered shameful to seek marriage advice. Consequently, the Balai Nikah was predominantly, if not solely, involved in marriage registration. Indeed, the Balai Nikah can also be utilised as a venue for the marriage contract (nikah). For the Bugis, however, marriage in Balai Nikah would be considered shameful: it would be assumed that this marriage was a result of premarital pregnancy (I. kawin kecelakaan; that the parents could not afford marriage expenses; or some other negative situation.

-

There are other differences between the situation that I found in Sidrap in 2009, and Nakamura's study in Kotagede in the late 1970s. In Kotagede, a wife would come to the Pengadilan Agama if her husband agreed to proclaim the dissolution of marriage. Also, as long as a wife had reasons based on Islamic law, whether or not her husband wanted to divorce her, a marriage can be dissolved through the Pengadilan Agama. Nakamura further adds that through Balai Nikah, a wife will not be divorced if her husband refused to divorce her. No matter which institution one should go to for the dissolution of marriage, whether Balai Nikah or the Pengadilan Agama, Nakamura argues that the dissolution of marriage is not based on who initiates it or the reasons for divorce. It is merely on the grounds of whether or not disputes exist according to Islamic law and the agreement of the husband to divorce has been determined by the related institution.[54]

-

In Nakamura's study, however, none of the cases analysed was from outside the court. In my study, in addition to the court, I also looked at cases in the community. This gave a more complete picture. Although in Nakamura's study people usually proceeded through the BP4 before the court, she found that the office of the BP4 had never been officially used for divorce counselling sessions. People usually came to the counsellors outside office hours, usually at night since they were already familiar with the counsellors. This made it easier for people to consult them about their marriage problems in informal and confidential circumstances.[55] Gavin Jones' study of divorce in West Java indicates that despite the state requirement to address marital problems through the BP4 prior to divorce, the BP4 did not have enough staff to deal with approximately thirty to forty cases per day.[56] Thus, encouragement to consult the BP4 prior to divorce is not compatible with the number of counsellors provided by the government. This situation results in insufficient consultation for the clients, and the concomitant reluctance of clients to consult the BP4.

Conclusion

-

The regulation of marriage and divorce in Indonesia reflects the formal instruments of the 1974 Marriage Law, but at the local level it continues to reflect local practices including the local accommodations to Islam, which have also been accommodated in the KHI which guides the decisions of Religious Courts. This is in spite of the fact that the Marriage Law was designed to standardise marriage and divorce. Some people ignore the law or still lack awareness regarding the law and follow other procedures which contravene religion and the Marriage Law of 1974. This is most evident in illegal/non-formal marriage (kawin liar) and divorce (cerai liar). It is also evident that in marital conflict men are less stigmatized and get more privilege than that of women. But, it is also evident that women are both victims as well as agents in regard to marital conflict. Local studies of marriage and divorce, including the cases of Sidrap reported here, indicate that the processes of handling marriage, divorce and reconciliation vary throughout Indonesia, including the practices of the state institutions.

-

The legal institutions for marriage, divorce and reconciliation do not function as intended. For example, in the Sidrap case, the Balai Nikah (incorporating the BP4) which were established not only for marriage registration, but also for marriage counselling is only used by the local community as an institution at which to register one's marriage. In order to seek marital conflict-resolution, all cases are brought to the Pengadilan Agama, or the problem is handled internally, amongst family members. Using the Balai Nikah/BP4 as marriage counselling is considered shameful for village people.

-

This study shows the limitation of national standardised procedures for dealing with marriage and divorce, which are firmly grounded in local customary practices and local accommodations to Islam. While the protocols established in the KHI, and the ways these are implemented by local Islamic courts, show flexibility, there is more to be done, especially in providing counselling to protect rights in marriage.

Endnotes

[1] Workshop on Marital Dissolution in Asia, organised by the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, 6–7 May 2010.

[2] Zaini A. Noeh, Peradilan Agama Islam di Indonesia (Islamic Religious Court in Indonesia), Jakarta: PT. Intermasa, 1980, p. 5. Noeh freely translated this hadith and considered the term 'lawful' to be an appropriate word to explain halal in this hadith.

[3] Personal interview with Pak Akhiru, a judge in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap, 10 May 2000, and I have heard this piece of advice mentioned a number of times during my observations in the court hearing in Sidrap.

[4] Undang-Undang Pokok Perkawinan Beserta Peraturan Perkawinan Khusus untuk Anggota ABRI, Anggota POLRI, Pegawai Kejaksaan, Pegawai Negeri Sipil (The Marriage Law and its Specific Regulation for Members of the Armed Forces, Police, Attorney and Civil Sevants), Jakarta: Sinar Grafika, Chapter VIII: article 38.

[5] Kathryn M. Robinson, 'Gender, Islam and culture in Indonesia,' in Love, Sex and Power: Women in Southeast Asia, ed. Susan Blackburn, Clayton: Monash Asia Institute, 2001, pp. 17–30; Hisako s, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' M.A. Thesis, Canberra: the Australian National University, 1981.

[6] Kathryn M. Robinson 'Indonesia women: from order Baru to Reformasi, in Women in Asia: Tradition, Modernity and Globalisation, ed. Louis Edwards and Mina Roces, Women in Asia Publication Series, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2000, pp. 139–69, pp. 146–47; Robinson, 'Gender, Islam and culture in Indonesia,' pp. 27–28.

[7] Peraturan Pemerintah (Government Regulation) No.9/1975, Chapter V: Reasons for Divorce, p. 19.

[8] Syaikh Kamil M. 'Uwaidah, Fiqih Wanita (Women's Fiqh), trans. M. Abdul Ghoffar, Jakarta: E.M. Pustaka Al-Kautsar, 1998, p. 427.

[9] Kompilasi Hukum Islam (KHI) (Compilation of Islamic Law), Chapter XVI: 115.

KHI, is a compilation of Islamic Law including various perspectives and is used as a guide or precedent for judges in the implementation of Islamic Law in the Religious Court. It contains a series of regulations which explain local norms of social interaction, and normative dimensions of functional interpretations of Islam. The application of KHI itself aims to mediate between religion (Islam) and local norms throughout the archipelago, and is used as a guide for judges of the Religious Court in solving problems associated with marriage, inheritance and property, regulated under Presidential Instruction No.1/1991.

[10] Zaini A. Noeh, Peradilan Agama Islam di Indonesia, p. 5.

[11] The number of Muslims in Sidrap increases from 90.92 per cent in 2000 (when the ethnographic fieldwork was conducted) to 95.31 percent in 2009. See Sidenreng Rappang in Figures, 2001, Badan Pusat Statistik (Central Statistics Bureau), Pemerintah Kabupaten Sidrap, Pangkajene and Sidenreng Rappang in Figures 2010, Badan Pusat Statistik (Central Statistics Bureau), Pemerintah Kabupaten Sidrap, Pangkajene.

[12] Another Bugis term for divorce is massarang, derived from the word sara (troublesome). Massarang carries the sense of being apart from each other, and is popularly used by the Bugis in Makassar. The term sipurang, however, is frequently used by the people in Sidrap, including in the court hearing.

[13] The paper is based on ethnographic fieldwork carried out between 1999 and 2000 and some occasional visits between 2003 and 2008. The data was collected using interviews and observations of both court hearings as well as everyday social practice.

[14] In the text, terms in languages other than English are rendered in italics. Each is followed by an indication of its language and then by an English gloss of its meaning, or vice versa. Most of these words are Bugis (B.) or Indonesian (I.), but some are Arabic (A.). Where many terms from one language, usually Bugis, are used in quick succession, only the first is identified.

[15] Personal interview with Pak Akhiru, 10 May 2000.

[16] Lontara' Membicarakan Tentang Berlaki-bini indicates the steps for handling marital conflict, it is available in microfilm at Campbell Macknight, South Celebes Manuscripts, Menzies Library, Canberra: the Australian National University, reel 5, no. 74, 1972, pp. 77–78.

[17] At the end of 2000, Fajar—a local newspaper—reported a murder case in which a husband had killed his wife in Pare-Pare, a neighbouring regency of Sidrap. It was suspected that the wife had been continuously abused during her marriage.

[18] Peter McDonald and Edeng Abdurahman, Perkawinan dan Perceraian di Jawa Barat (Marriage and Divorce in West Java), Jakarta: Lembaga Demografi, Fakultas Ekonomi, Universitas Indonesia, 1974, p. 6; Gavin W. Jones, Yahya Asari and Tuti Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' in Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 25, no. 3 (Autumn 1994): 395–416.

[19] See Kompilasi Hukum Indonesia (Compilation of Islamic Law), Chapter XVII: 116d: reasons for divorce.

[20] Interview with Tikka (aged 40), housewife, three children, divorced, primary school education, 10 May 2000, Pengadilan Agama, Sidrap.

[21] Barend ter Haar, Adat Law in Indonesia, International Secretariat Institute of Pacific Relations, 1949, cited in Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 37.

[22] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 37. Nakamura studied the dissolution of marriage through the courts and related institutions rather largely neglecting local discourse and individual practice. This is a limitation of her study and its use in comparative studies, as it is difficult, if not impossible, to study the nature of religious faith without addressing everyday social practice.

[23] See, for example, Kathryn M Robinson Stepchildren: The Political Economy of Development in an Indonesian Mining Town, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986, pp. 224–25.

[24] The waiting period (A. iddah) refers to the period of abstention from sexual relations imposed on a widow or a divorced woman, or a woman whose marriage has been annulled, before she may remarry. There are two types of iddah, one is iddah because of the death of the husband (a period of four months and ten days), and the other is iddah because of divorce (a hundred-day waiting period or three menstrual periods).

[25] Only after all these steps can a woman remarry her previous husband. A marriage for the purpose of returning to her former husband (A. muhallil marriage) is unlawful (see, for example, 'Uwaidah, Fiqih Wanita, pp. 385–86; and Rahmat Sudirman, Konstruksi Seksualitas dalam Wacana Sosial (The Construction of Sexuality in Islamic Discourse: the Transformation of Interpretation on Sexuality), Yogyakarta: Penerbit Media Pressindo 1999, pp. 87–88. In fact, I did not see a single case of muhallil marriage handled by the Religious Court Sidrap.

[26] This is also stated in Kompliasi Hukum Indonesia, Chapter XVIII, 163: reconciliation, p. 1.

[27] Silisuang is derived from the words si (mutual) and lisu (to return), so silisuang carries the meaning of reconciliation on the grounds of mutual consent (husband and wife), regardless of who initiates it.

[28] PKK stands for Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (Family Welfare Movement). Dharma Wanita (Women's Duties) is a state-sponsored organisation for the wives of civil servants—whose membership is compulsory.

[29] In Indonesia, plural marriage is termed polygamy instead of polygyny since polyandry (a woman having more than one husband) is illegal.

[30] For a discussion of unofficial marriage (kawin liar), see Nurul Ilmi Idrus, '"It's the matter of a piece of paper": between legitimation and legalisation of marriage and divorce in Bugis Society,' in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue19/idrus.htm, 2009, accessed 30 October 2012.

[31] Even if the principal foundation of the Marriage Law No. 1/1974 is based on monogamy, polygamy is permitted for Muslims under certain circumstances. These circumstances emphasise the wife's duties and neglect her rights. Take for example, Chapter VIII (article 41a) of the Implementation Regulation which states that polygamy is allowed under the following circumstances: if the wife cannot perform her duties as a wife, if the wife is handicapped or suffers from disease which cannot be cured, and if the wife cannot bear a child. These circumstances contradict another chapter in the Marriage Law (Chapter VI, 34:1) which states that the husband must protect his wife and provide for household needs to the best of his abilities. This is difficult to fulfil if the husband has more than one wife.

[32] During the period of separation, it was Pak Bakri's wife who was afraid of being divorced because they had six children and she was not working in the paid workforce. As a result, she tried as much as possible to avoid Pak Bakri, because she was afraid that he would ask her for a divorce.

[33] Julia Suryakusuma, 'The state and sexuality in New Order Indonesia,' in Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia ed. Laurie J. Sears, Durham: Duke University Press, 1996, pp. 92–119, p. 109.

[34] Interview with a number of wives of civil servants in Sidrap and Makassar, 2000.

[35] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims'; Jones, Asari and Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' p. 402.

[36] According to a clerk of the court (case receiver in the first stage), the number of cases of divorce does not show a big difference from year to year, around 300 cases (personal interview, 31 July 2002). But, it increases significantly over the last ten years (see Table 1).

[37] See Daniel S. Lev, Islamic Courts in Indonesia: A Study in the Political Bases of Legal Institutions, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972, p. 123.

[38] Jones, Asari and Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' p. 402.

[39] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 140.

[40] The category of male infidelity is according to the wife who files for divorce. This contrasts with the marriage records in Soppeng (South Sulawesi) which indicate that moral crisis refers to female infidelity (Susan Millar, Bugis Weddings: Rituals of Social Location in Modern Indonesia, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1989, p. 27.

[41] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 115.

[42] Hildred Geertz, The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization, New York, NY.: The Free Press of Glencoe, Inc., 1961, pp. 139–42.

[43] Millar, Bugis Weddings, p. 27.

[44] Badan Penasihat Perkawinan, Perselisihan dan Perceraian (BP4), the Body for Marriage Disputes and Divorce Counselling, is attached to the Kantor Urusan Agama (KUA): the Office of Religious Affairs. The first BP4 in Indonesia was established in Bandung in 1954, see Lev, Islamic Courts in Indonesia, pp. 191–203.

[45] At the subdistrict level of the regency, Balai Nikah functions as the KUA.

[46] See also Jones, Asari and Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' p. 409.

[47] To get to the Religious Court in Pangkajene, I had to take pété'-pété (mini-bus) to Rappang, then took another pété'-pété' to the terminal in Pangkajene, and from there I took a tricycle to the Religious Court.

[48] Ten days before a marriage, an investigation is required by the Pegawai Pencatat Nikah (PPN, marriage registrar) and the prospective bride and groom are required to consult the BP4 (Badan Penasihat Perkawinan, Perselisihan dan Perceraian—Institute for Marriage Disputes and Divorce Counselling) for pre-marital advice. PP No.9/1975 (Chapter II, 3:3), however, states that an exemption can be given for urgent reasons, such as one of the couple will be going on duty abroad. The exemption will be given by the subdistrict head (I. camat) under the authority of the regent (bupati.

[49] Personal interview with Ibu Husnang, a staff member of the BP4 who deals with counselling and marriage registration, Makassar, 14 February 2000.

[50] For example, BP4 Makassar does not provide a specific room for counselling. Clients discuss their marriage problems in an open room, where they can be witnessed and overheard by others.

[51] Since the establishment of a woman's crisis centre LBH-P2I (Law Service for Indonesian Women Empowerment) in 1995 in Makassar, this has become an alternative marriage counselling centre, particularly for women who are the victims of violence. Even though this centre offers counselling for men and women, all clients are women. Even though the statistics on violence against women from LBH-P2I are small, they grow every year.

[52] See Jones, Asari and Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' pp. 401–02.

[53] The ideal procedure of counselling starts from BP4 where the couple is advised in regard to their marriage disputes. If the marriage can no longer be continued after the counselling process, the case will be continued in Religious Court. See also Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 59.

[54] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' pp. 70 and 59.

[55] Nakamura, 'A study of dissolution of marriage among Javanese Muslims,' p. 69.

[56] Jones, Asari and Djuartika, 'Divorce in West Java,' p. 411.

|

Figure 1. A Court Hearing in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap. Photographed by Nurul Ilmi Idrus, 2000.

Figure 1. A Court Hearing in the Pengadilan Agama Sidrap. Photographed by Nurul Ilmi Idrus, 2000.