Defeating Patriarchal Politics:

The Snake Woman as Goddess:

A Study of the Manasa Mangal Kavya of Bengal

Saumitra Chakravarty

-

The worship of the snake goddess Manasa, popular in rural Bengal, belongs primarily to the domain of the womenfolk and is part of their daily struggle against adversity through a plea for divine intervention. Simple domestic worship to Manasa forms part of the large repertoire of rituals, chanting and narration through which rural women seek to placate rural goddesses who, on the whole find little mention in Vedic Hinduism. Though the snake does occupy an important supportive role in Hindu myths as part of Shiva's girdle, the crown of his matted locks or in Vishnu's canopy, Manasa as a snake goddess may be traced back to pre-Aryan goddess mythology. Literary historian, Asit Kumar Bandopadhyay,[1] believes that goddesses like Manasa, Chandi, Sheetala, Shashti and Bashuli,[2] are, even today, worshipped by rural women within their homes with simple non-Vedic rituals. He argues that this form of worship may be traced back to the tribes of Proto-Australoid origin who inhabited the plains of eastern India before Aryan settlement. Vestiges of this culture and form of worship lingered on amidst the lowest castes of the Hindu hierarchy who mingled easily with the tribes even after the Aryan influence swept the region.

-

This goddess-based tradition is therefore typically a folk one, displaying the last vestiges of pre-Aryan rituals, and even today practised among rural Bengali women. It is celebrated through the chanting of rhymes, panchalis (a long narrative celebrating the glory of a deity) and vrata katha (rhymes and narratives chanted on the occasion of the performance of a vow). By the fifteenth century, all these oral practices had crystallised into the genre of the Mangal Kavya. The Mangal Kavyas gained their popularity among the rural masses as a result of the Turkish invasion of Bengal in AD 1203. The imposition of foreign rule and the religious exploitation of the local Hindu population by the invaders and their agents (as shown in the text), led to the propagation of the Mangal Kavyas as a plea for divine intervention by the common people through the chanting of these texts and the performance of non-Vedic ritualism to appease the goddesses who appear as various manifestations of an Abhaya Shakti (one who dispels fear and poverty among her votaries). The Manasa Mangal, composed in the late-fifteenth century belongs to this Mangal Kavya tradition—a literary genre particular to Bengal between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

-

This genre owes its name to the Ashtamangala songs sung by rural women on Tuesdays (Mangalvara, associated with Mangalgraha or Mars) in eight palas throughout the day and the night over a period of eight days. These songs are generally addressed to a female deity in her incarnation as Sarvamangala or Mangalmayee (mangala indicating her benevolent form). Asit Kumar Bandopadhyay defines the Mangal Kavya as a local epic, a legendary narrative poem in the lachari metre, (a Bengali metre suitable for dancing during the eight-day narration of the legend of Manasa, the snake goddess or other female deities in other Mangal Kavyas), performed through song, dance and theatrical representation and depicted through locally painted scrolls narrating the story behind each of the scenes. These are presented during the performance at fairs and marketplaces.

-

But since myths narrated in the Mangal Kavyas are also recited by rural women within their homes during ritual observances, I will devote the first section of this paper to the practice of chanting the myths associated with these female deities by the rural women and the performances of the simple rituals associated with them. In the second half of the paper, I will provide a gendered analysis of the text of the Manasa Mangal.

-

The vrata kathas are seen as a solution to all the immediate problems of the rural population through the worship of female deities. The ritual recitation of each represents the manifestation of a particular fear associated with village life. For these are goddesses who are easily propitiated and equally easily angered, granting boon and curse with equal propensity, achieving impossible rescues, reviving dead people and lost merchandise, reinstating ruined kingdoms for the faithful and killing and destroying with equal frenzy the kith and kin of the skeptic and the non-believer, as enshrined in the myths associated with them. The Manasa Mangal (a rural epic devoted to the snake goddess Manasa, ritually chanted) says of the worship of Manasa (also referred to as Padmavati in the text):

Puja na koriya jeba kore upahas

Padmar kopete hoi swabangsha naash

Bhakati koriya jeba korye pujan

Manobhishtha siddha tat hoy tatkkhan[3]

(Whoever does not worship her or treats her with disrespect will be destroyed along with his family by the anger of Padma/Whoever worships her with faith, his/her aspirations will be instantly fulfilled)

-

This form of worship to these local goddesses, is the only safeguard that villagers have against the many ills that plague their daily lives—poverty, disease, inclement weather, crop failure, domestic distress. Unlike most Scriptural texts in Hinduism, this is part of a rich oral tradition preserved largely within the sanctity of the home by rural women. The simple faith that underlies this chanting may be seen in a typical advisory for the village folk in all these narratives—whoever chants this narrative will get long life, freedom from poverty, the childless will be blessed with a son, the spinster with a husband. The Manasa Mangal says that whoever keeps the sacred pot of Manasa within the home will enjoy the bliss of heaven after death for three generations, whoever keeps this sacred text of the Snake goddess narrative or the Padmapurana or Manasa Mangal (of Manasa/Padma) within the home, will never face domestic discord.

-

Since the worship of all these female deities arises from the need for a solution to a particular problem in village life associated with each deity, worship and recitation are seasonal. Manasa is worshipped during the monsoon month of Sravan (mid-July to mid-August) when snake bite is a common ill. Worship is normally centred on the women folk, without priestly intervention and with simple, non Vedic rituals and low-cost accessories of ritual observance. The Chandi Mangal (a similar epic devoted to the goddess Chandi, also ritually chanted) notes that women need offer no more than eight lotuses, eight betel leaves and eight stalks of the sacred durba grass. To celebrate Manasa's worship in the villages of Bengal, there are Manasa-baris, small mud huts housing painted clay pots decorated with snake hoods and filled with water to indicate the womb, thus denoting an image of fertility. The village women worship Manasa through these sacred pots, on which the householder places a branch of a tree. Unlike the monopoly of the upper castes in Vedic religious practice, particularly of the Brahmins and the ostracisation of the lowest castes, (who are even today debarred from certain temples), the Ashtamangala songs and form of worship envisage a more egalitarian concept among the village women, where worship is performed regardless of caste.

-

To pass on now to the text itself, the Manasa Mangal follows the typical story line of the Mangal Kavyas, that of a goddess of pre-Aryan origin soliciting worship from the staunchly Shaivite (worshipper of Shiva) upper classes and involving heavenly beings born to earth by virtue of a curse, to accomplish this mission. There are several versions of this text composed by several poets across almost three centuries of the Mangal Kavya tradition, but the best known of the Manasa Mangals is that of Bijoy Gupta, the text under consideration in this essay. The Manasa Mangal begins with goddess worship originating among the lower classes such as fishers, shepherds or the Chandals who are the lowest class in Hindu hierarchy, entrusted with execution of criminals. Owing to their low position in the Hindu caste hierarchy, the Chandals are not included in Hindu worship and ritual observances, but here in the text, the poet shows Manasa being worshipped by them. But the principal story line of the text in the Manasa Mangal, expresses the snake goddess Manasa's desire to be accepted by Chand Saudagar, the patriarch of the rich and powerful merchant community. Being a strong Shaivite, Chand Saudagar resolutely refuses worship, despite the trials, tribulations and tragedies the goddess Manasa showers upon her victim with all the fury of a woman scorned. As in other Mangal Kavyas like the Chandi Mangal, which show the absorption of these goddesses into the Hindu pantheon as mere appendages to powerful male gods, here too Manasa is projected as Shiva's daughter. But unlike the domesticated image of Chandi in the Puranic sections of the Chandi Mangal, in the Manasa Mangal, the aloneness and the rejection of Manasa the rebellious female, by forces both human and divine, are constantly stressed. The focus of this part of the paper therefore revolves around the single abusive phrase Chand Saudagar, Manasa's principal enemy in the story, constantly hurls at Manasa at every juncture of the text: 'Laghujaati Kani'—the one-eyed woman of low caste. Manasa's battle for recognition as projected by the poet Bijoy Gupta, is not only a gender war but class warfare too, for Manasa, unlike Chandi or Lakshmi in other Mangal Kavyas, is not acceptable to the divine cosmogony. Born as she is through Shiva's sperm falling on a lotus leaf and trickling down its stem into the underworld, she is known both as Padmavati (born in the lotus grove) and Manasa (Shiva's manas kanya or mind-born daughter) but without any of the powers and privileges thereof. She remains an outcaste who single-handedly wages war against the bastions of patriarchy in all its human and divine forms.

-

The epithet Kani or one-eyed, while challenging the traditional celebration of feminine beauty in the goddess cult, also indicates a Tiresian blindness of the pronounced binaries of higher and lower categories which patriarchy accentuates. Joseph Campbell notes,

In the older mother myths and rites, the light and darker aspects of the mixed thing that is life had been honored equally and together, whereas in the later male-oriented patriarchal myths, all that is good and noble was attributed to the new heroic master gods, leaving to the native nature the character only of darkness—to which also a negative mental judgment was added.[4]

Manasa, arising as she does from the heart of the underworld as a snake goddess, with her knowledge of magic and of forest remedies, her powers of maya, represents that essentially organic, vegetal, changeable, non-heroic view of Nature.[5] Chand Saudagar, a staunch Shaivite and an honoured patriarch of the powerful merchant community, therefore rejects her as a non-member of the conventional Hindu pantheon. As he tells his wife Saneka, who is committed to snake worship like most rural women in the riparian state of Bengal,

Angaheen devatar puja aache mana[6]

(Our religion forbids the worship of non-iconic gods)

-

Manasa's birth in a lotus grove (incidentally the lotus also represents something which arises from a bed of slime), through Shiva's sperm falling on a lotus leaf, circumvents the female womb, yet does not crystallise the female Shakti (Goddess power) as represented for instance by Chandi in her many forms of demon-destroyer as celebrated in traditional Hindu goddess mythology. Throughout the text, the only iconic form Manasa adopts for her worshippers is that of the kumbh or sacred pot. Both the lotus of her birth and the pot she is represented by, are recognised as older anthropomorphic fertility symbols. A.P. Jamshedkar, speaking of a similar iconic form of the Lajjagauri (another goddess represented by the lotus and the pot), says that the lotus symbolises creation and that the earthen pot stands for Mother Earth, giving birth to all creation and giving shelter in her womb.[7] Thus Chand Saudagar's repeated desecration of Manasa'a sacred pot and his defilement of the consecrated offerings, (which represent both plant and animal life), are assaults on the creative processes of the earth and the symbols of fertility. This results in the death of his seven sons, rendering him without an heir. This has serious social, material and spiritual connotations, making him an outcaste in his own community:

Padmar bibade she harailo shakal

Putraheen loker nahik paralok[8]

(He lost all through his conflict with Padma, for a man without a son has no chance of salvation after death)

-

As noted by Monica Sjoo and Barbara Mor, 'the serpent of chaos is originally and always a woman's body.'[9] We know that with the advent of androcentrism, the cultural repression that followed is represented in western mythology by myths like those of Apollo's slaughter of the python serpent of the Mother, Perseus' slaying of Medusa by Athene's

|

|

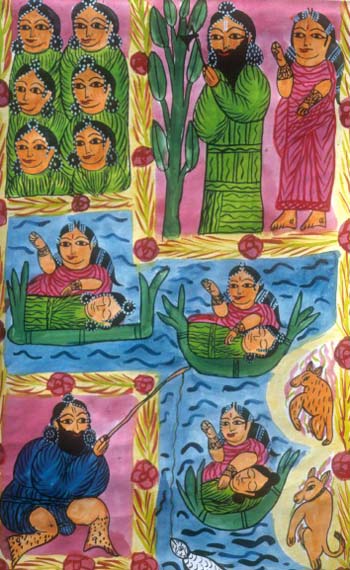

aid or St George's dragon-slaying.[10] The cultural repression of the goddess is associated with the rejection and negation of older Goddess myths and forces— as evil, venomous facades of witchcraft. Throughout the Manasa Mangal, the rejection of Manasa by the powerful patriarch Chand is emphasised through the constant switching of roles of Manasa between Devakanya, Shiva's divinely beautiful daughter, and Nagkanya, the serpent woman dressed in snake vestments, snake jewellery, armed with serpentine weapons, riding a snake chariot and followed into battle by a retinue of ninety-nine deadly snakes (see Figure 1). In this guise Manasa is an object both of fear and scorn in the divine assembly. The two roles of Manasa also represent the ambiguity of her position as destroyer and rejuvenator, which is the essence of goddess cults as represented in the Mangal Kavyas. It is she who initially destroys the six sons of Chand and then, paradoxically, restores the fertility of his wife, Saneka—a woman who is well past her prime and grieving the loss of her sons. It is she who kills the seventh child, Lakhinder, born by her own machinations to serve her purpose of propagating her cultic status. Again it is Manasa who re-fleshes Lakhinder's rotting bones, restores his masculine potency and later revives his six brothers on condition that Chand worships her.

Figure 1. Folk image of Manasa in earthen pots. Source, Jim Robinson, Manasa pat, 'Patua painting' in Clay Images of WestBengal, online: http//www.clayimage.co.uk/patua.html,

site accessed 14 July 2010.

|

-

The ambiguity of her appearance as Nagkanya in the text also represents the dark, nascent forces of unbridled female sexuality. Unlike Chandi, Shiva's consort in the Chandi Mangal, who is repeatedly shown as a domesticated wife and mother, Manasa appears as the femme fatale who destroys a man by defeating his potency—sexual, physical or spiritual. Shiva lusts after this beautiful maiden in the lotus grove, unable to recognise her as his own manas kanya. Manasa repudiates Shiva's advances

Sansarer Naath hoiya pade pade ghati[11]

(Being the lord of the Universe you stumble to temptation at every step)

-

Rejecting advances on her chastity, Manasa is nonetheless partially blinded by Shiva's jealous wife Chandi. Manasa is exiled to the forest and given in marriage by her father to the stern, austere seer Jaratkaru, who represents Brahminical power at its peak. Refusing to be humiliated and insulted by him and to be subjugated in a marriage, Manasa renders his apparently invulnerable Brahminical power useless, under the force of her venomous sting:

Padmar kope more muni kaal bisher jhale

Kothai jap, kothai tap, kothai borai[12]

(The sage was felled by Padma's anger and her deadly venom. Where then was his japa-tapa, his hermit's powers of prayer and meditation, his Brahminical arrogance?)

-

Sabotaging her own marriage, she conceives eight deadly snakes without male impregnation and becomes the mother of the Lords of the underworld. Shiva and his consort Chandi are themselves not immune to the deadly power of her venom, and must be restored to life again by her intervention alone. She wages war against Yama, and becomes the death-bringer of the Lord of Death himself:

'Jomer Jom' [13]

(Yama's Yama)

as the poet ironically puts it. Wrapped in her serpentine coils, Yama is rendered impotent and the life and death cycles of the universe suffer, shaking the very foundations of divine order. The succubus image here represented is repeated throughout the text. She penetrates the hermetically sealed marriage chamber of Chand's last son Lakhinder, robs him of his male potency and later his life, rendering his young wife Behula, a virgin widow. In the guise of a beautiful courtesan, Manasa fatally attracts Chand Saudagar her deadliest enemy, and cleverly robs him of his ancestral wisdom, knowledge and his powers of divination, which are the sources of his impregnable social position and his antidote against her destructive attacks. She poses a serious challenge to Chand Saudagar's Shaivism and uses every weapon in her armoury to convert him to snake goddess worship. She kills his seven sons, sinks his fourteen ships laden with merchandise and leaves him floundering and spluttering in the middle of the river. This represents the vengeance of women marginalised by society and religion. Chand is flung, denuded and stripped of his manhood and pride, on an unknown island. Accompanied by the mocking laughter of Manasa, he is stripped of the last vestiges of human dignity, covers his nakedness with his bare hands in her presence, begs and forages for morsels of food, is humiliated and beaten and remains unrecognised by his own subjects. Manasa thus strikes at the threefold foundations of patriarchy in the text—the androcentric Hindu pantheon of gods, the Brahminical priestly power and the wealthy merchant community that controlled the economy of contemporary society.

-

The resolution of the deadly conflict between the vengeful Manasa and the unrepentant Chand can only be facilitated

|

|

by another powerful woman, Chand's young daughter-in-law, Behula. She is learned beyond the limits of contemporary feminine wisdom in herbal remedies, powerful mantras and the knowledge of reviving the dead. Behula, who becomes a virgin widow on her wedding night by Manasa's machinations, steps beyond the prescribed periphery of womanhood by refusing to ascend her husband's funeral pyre for sati. Instead she courageously embarks on a six -month odyssey with his body, floating alone and unprotected on a raft made of the banana plant to appease the gods and revive her husband Lakhinder (see Figure 2). In so doing, she has violated every conventional norm of patriarchy:

Shashur shashuri aar baap bhai rakhe

Swatantar hoile taar nana dosh theke

Sati pativrata houk dharma te tatpar?[14]

(A woman should be in the safekeeping of her in-laws, her father and brothers. Independence brings about the fear of lost chastity. A woman should be chaste, religious and subordinate to her husband).

Figure 2. Behula with dead Lakhinder on her odyssey. Source, Jim Robinson, Manasa pat, 'Patua painting' in Clay Images of WestBenga, online: http//www.clayimage.co.uk/patua.html, site accessed 14 July 2010.

|

-

At the end of the text, it is Behula who persuades her arrogant father-in-law Chand, after the revival of his sons and the recovery of his lost ships and merchandise, to worship Manasa, if only with his left hand. The right hand is reserved for the worship of the male god Shiva. It cannot be defiled by worship of a female—especially an unacceptable one like Manasa. At the end of the Manasa Mangal, we see Manasa merging into the archetypal figure of the feminine divine. The hymnic section in this part of the text celebrates her as Sarvadukkhanashini (one who removes all grief), Jagatmata, Vishwajanani (the universal image of the Mother Goddess), benevolent to her votaries. As in other Mangal Kavyas devoted to other folk goddesses, the eventual image here is that of convergence into the Adyashakti, the Universal Female Power, which represents Creation, Preservation and Destruction. Thus, folk and classical traditions merge at the conclusion of the text, illustrating a powerful resurgence of the cult of the Goddess over the eroding forces of patriarchy.

Endnotes

[1] Asit Kumar Bandopadhyay, The Complete History of Bengali Literature, Calcutta: Modern Book Agency Pvt. Ltd., 1995, p. 50.

[2] These, goddesses are need-based, arising out of the contemporary situation. Manasa is a snake goddess; Chandi was originally a hunter goddess worshipped for protection against wild animals; Sheetala a goddess of small pox; and Shashti, a goddess bestowing children.

[3] Bijoy Gupta, Manasa Mangal, Calcutta: Beni Madhob Seal's Library, 2008 ed., p. 51.

[4] Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology, London: Souvenir Press (Educational and Academic), 2001, p. 21.

[5] It is interesting to note from an analysis of the don songs of the Santhal tribes that like most indigenous people, they too do not believe in the dichotomy between sky and earth, male and female. Instead, as Prof. Onkar Prasad shows us by the principle of cosmogony, the union of contraries is necessary for the return of fertility to the land and to the woman. See Onkar Prasad, 'Primal elements in the Santhal musical texts,' in Prakrti: The Integral Vision, vol. 1, New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (Pvt) Ltd., 1995, p. 116,

[6] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 65.

[7] A.P. Jamshedkar, 'Symbols, images and rituals of the mother,' Journal of Oriental Art, vol. 30. New Delhi: Lalita Kala Akademi, 2004, pp. 23–40, p. 25.

[8] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 100.

[9] Monica Sjoo and Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother, San Francisco: Harper, 1991, p. 250.

[10] The name Medusa is etymologically associated with medha in Sanskrit, metis in Greek, and maat in Egyptian. See Tracy Marks, 'Medusa in Greek mythology,' in Webwinds, 2007, online: http://www.webwinds.com/thalassa/medusa.htm, accessed 15 Feb 2009. The snake itself, due to its power of sloughing off its skin is thought to represent rejuvenation after death and the continuity of the life cycle. The rainbow serpent is a symbol of integration among indigenous people in many parts of the world like Africa, America and Australia. It links binaries and encircles the world to unite disparate elements.

[11] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 8.

[12] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 28.

[13] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 115.

[14] Gupta, Manasa Mangal, p. 240

|