Grandmothers, Grass Skirts and a Little Piece of Paradise

Pamela Zeplin

Figure 1. Untitled (P. Zeplin), 2010, photographer Matt Huppatz.

-

She could never imagine that a garish grass skirt could come to mean so much. It emerged from under a winter raincoat hanging on a coat hook in the hallway of her home and must have been there, she realised, for more than a decade. In that moment of re-discovering this piece of cheap tourist kitsch, she smiled, remembering how it came to define a very special relationship during one of the happiest times in her life. This was a relationship between a toddler and a woman of a certain age. The little grass skirt may have been incidental to the deeper bond between them but for her, it was deeply imbued with memories and stories that belied its tatty raffia reality. The garment conjured up a very personal Pacific; of desire and dancing and a kind of bodily enchantment—precisely those taboo qualities of paradisiacal 'otherness' bedevilling this region for centuries.

-

Before she travelled to Western Samoa (as it was known in 1996), she was, in most senses, just another forty-something, single academic woman working in the visual arts. The Festival of Pacific Arts in Apia pretty well changed all that. Well, whether this was entirely true is neither here nor there: it certainly felt that way and the following story relates how this came about.

A new role

-

Perhaps what distinguished her from her other middle-aged colleagues in the art school where she lectured was a passion for flying and research throughout Southeast Asian countries and those in Oceania (at the 'other') end of the Asia-Pacific hyphen. But more importantly, she harboured another particular passion, a new life experience that was as illicit as it was delicious.

-

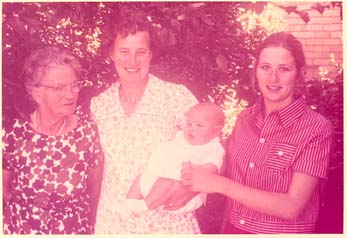

She had in 1995 become a grandmother and a pretty good one at that, she thought. Later she would learn that this bright shining new infatuation was anything but unique and fascinating to those beyond this enchanted domain. To others, most grandparents are shamelessly besotted, even tedious, and she had willingly become an embarrassing bore.

Figure 2. The new Nanna, 1995, Anon.

Figure 2. The new Nanna, 1995, Anon.

|

Figure 3. The new grandchild, c.1947, Anon.

Figure 3. The new grandchild, c.1947, Anon.

| |

In this new role, it also became increasingly evident that unlike other cultures, children are rarely at the centre of western society's core business. For all the academic posturing about postmodern pleasure and play, the body and jouissance, it was traditional research paradigms that nevertheless prevailed. It was all terribly serious and body talk was, of course, distanced, ironic and confined to learned journals. Amidst the black gothic gloom characterising much intellectual life, university art schools were tolerated with amusement as sandpits of recalcitrant if colourful 'adolescents'. Unless you lived in Brisbane, academics wearing bright colours were deemed suspect and not to be taken seriously—rather like conducting research in the Pacific. As for the subject of children, this was taboo, even within art schools, not because of 'paedophilia' issues but, worse, because it was considered sentimental.

-

Away from work she was deeply smitten with the new little pixie girl child and quickly realised, as do many paternal grandmothers, that in order to participate meaningfully in her first grandchild's world, she would have to shift her own life around. Before the new child arrived, the (other) maternal grandmother had already done just that by retiring, in her late 40s, from work. She had to act swiftly.

-

With a full-time job (on which she thrived), a travel habit and little in the way of superannuation, retirement was not an option so a creative solution was required. In the 1990s academic staff were expected to conduct research one day a week—usually away from the university—and this was a sacrosanct arrangement unless an institutional emergency arose. A window of opportunity thus opened, so once her daughter-in-law resumed work, research Mondays became Marvellous Mondays for the grandmother. Research was discreetly moved to evenings, early mornings, weekends and public holidays—any time except Mondays between 7A.M. and 3 P.M..

-

This clandestine arrangement continued blissfully for two and a half years, unknown to almost everyone except family and close friends. During that time, a couple of unavoidable work meetings demanded her attendance. Wearing an air of insouciance and purposefully pushing a collapsible stroller, she elicited from her colleagues only quizzical glances, a grunt or two and a query as to whether there was, 'well … something wrong' with the gentle wide-eyed toddler in the grass skirt. 'Yes', she replied sarcastically, recalling some of these colleagues' obnoxious art brats, 'she carries "very special" genes.' At one particularly rancorous meeting, the little two year old silently climbed onto her knee, placed a glittering plastic tiara on her grandmother's head, slipped off again and returned to her toys in the corner of the room. Her Nanna left it on and all bullying ceased.

A genealogy of nannas – at home and abroad

-

Having no experience of being grandmothered through her own childhood, she had to invent this role of paternal grand-matriarch. Her own mother had provided an exemplary and loving grandmotherly model to her only son but she could never quite understand how her Mum/his Nanna could possibly love her secondary offspring so much—at least until her boy became a father at twenty-five.

-

In 1994 she had dreamed this girl baby at a time when her mother was dying. She was therefore overcome with joy at the child's impending actuality but when the grandmother-to-be brought the news that a little one was on the way, her mother explained, apologetically, that she couldn't wait for her and didn't think she would be able to look after babies any more. 'You'll be a good grandmother' was her reassuring benediction. But how could she ever emulate such a deep inter-generational bond while conducting a full-time career? Now living away from extended family, and without access to her mother's 'secret grandparenting business', she would have to invent her own form of granny manual.

-

She could barely remember her own paternal grandmother, who paled into bland insignificance beside the fierce and, everyone whispered, insane, grandfather. As for her more forthright maternal grandmother (also called Nanna), she had only met her on a few occasions, mostly in Melbourne where her nuclear family lived a diasporic life, and twice in Perth, where both extended family groups (the 'outlaws', as her father called them) remained. Throughout childhood, however, she was regularly subjected to the family refrain: 'you're just like your grandmother'. She assumed this was something to do with tactlessness.

Figure 4. Together: Four generations, 1969, Anon.

-

This didn't deter her from seeking a closer affinity with this senior woman in the family, who, like most grandparents, remembered birthdays and school achievements. In faraway Perth this Nanna was swamped by loving grandchildren but her eldest granddaughter in Melbourne missed having her in her life. However, there was something else that intrigued her about this sharp-tongued grand-matron which signified larger possibilities beyond this grandchild's suburban existence in Victorian Housing Commission Jordanville. Ancient sepia photos of her mother at childhood fancy dress parties revealed a long-forgotten world of play, dance and exotic costumes, even during the Great Depression.

Figure 5. Fancy dress party, Narrogin, 1920s, Anon.

-

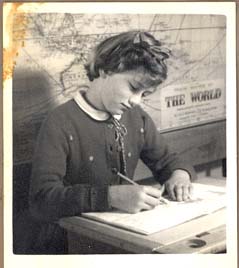

Four decades later as a six-year-old on a memorable holiday in Perth with her Mum and brother this grandmother (and the maternal Grandad she met only once) lavishly nurtured her love of drawing with gifts of art materials and creative encouragement. Widowed later in life, this same maternal grandmother exercised another profound if unconscious influence on her distant granddaughter's life. In her senior years the Perth Nanna's preferred status was self-sufficiently single and despite an exceptionally difficult life, she was always 'well turned out'. She was direct, she got around, she danced, she fell in love and she travelled.

-

Exotic packages would arrive in Jordanville, purchased in Aden or Alexandria or Stratford-on-Avon;

Figure 6. School Photo, 1958, Anon.

Figure 6. School Photo, 1958, Anon.

| |

a collapsible brass table or a pink plastic slide viewer with tantalising scenes of Egyptian pyramids. Then there were enthralling souvenirs of England, this grandmother's birthplace—a glamorous Royal Family, red double-decker buses and busby-headed guards. Before television entered everyone's lives, these glimpses of foreign otherness provided a rich source of wonder for the neighbourhood kids, teachers and schoolmates. Although her life was happy, there were now other lives, other lands to wonder about, and geography soon rivalled art in her childhood fantasies—which strongly featured tropical islands. The Littlest Mermaid became her favourite book. A school photograph taken when she was about nine presciently captures these two life pathways of art and travel. Primly posed in front of a map of 'The World' and drawing (or is she writing?) in a school exercise book, her head is positioned beneath the equator, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

|

A flower behind the ear

-

By the time she was a teenager, the most enduring image of this worldly Nanna was an old family photograph, a black and white picture that would, she realised in retrospect, remain lodged in her unconscious and resonate throughout her life. After her voyage to Samoa in 1996, she recalled a strong affinity with this picture. Reaching across time, this long-since forgotten image in a grey cardboard family album, tattered and softened with generations of touching, was different from all the others. It seemed to signal the possibility of alternative trajectories for her life than those mapped out along conventional vectors; the kind of experiences, however, that had never been available to her mother.

-

The photograph in question was taken on board ship at a time when travel was incredibly expensive, terribly

Figure 7. A grandmother abroad, Anon.

Figure 7. A grandmother abroad, Anon.

| |

exotic and usually experienced leisurely by sea rather than rapidly by air. The photo hinted at the allure of the tropics and she always understood this as the Pacific, even though it was obviously taken somewhere in the Indian Ocean on a voyage to or from England. It featured her middle-aged grandparent looking slim, smart and glamorous on the deck of SS Kanimbla (or was it the SS Orcades?). She recalled her grandmother wearing a lei and flowers behind her ear, adornments of exotic glamour and excitement for a far away granddaughter growing up in 1950s Australia where other kids' grandmas wore frumpy floral frocks, aprons or dowdy black crêpe. Half a century ago leis and flowers carried heightened meaning; they indicated very special occasions; party time, frocking up and serious dancing.

Thirty-five years later she would inherit her grandmother's fake amethyst engagement ring, also from the Middle East, given to her by a soon-to-be-rejected suitor on board that ship. This heartless decision puzzled the granddaughter for many years until she reached the same age; then she could at last understand why a woman in her fifties would reject apparent undying love, especially if it meant relocating to a farm—or, in the granddaughter's case, a village in the South Seas.

|

-

Fingering this purply piece of jewellery, she wondered who had taken this photo of her Nanna? Was it the suitor? More likely, a professional photographer; they were everywhere in the days before the box brownie and the photograph's surface still retains that crisp contrast and texture typical of studio production. Was it taken at an on-board dance, a ball or just a dinner? Why did passengers afloat make such sartorial efforts? And did glamour on deck ward off the real terrors lurking on the high seas?

-

As a child captivated with this image, she would conjure up the moments after this photograph was taken; a storm and a shipwreck would magically transport her grandmother to an idyllic tropical island, where she lived happily ever after with a handsome and hybrid prince-chief. He, of course, would adore her grandchildren, invite them for holidays and decree feasts and dancing with leis and 'hula' skirts—with little mermaids looking on.

Figure 8. Tim visiting, 1996, photographer, P. Zeplin.

Dance as other: Australia in the 1950s and 1960s

-

For many 'fifties Australian families the idea of dancing suggested a kind of 'other' glamour—something people did at weddings, dinner dances, socials and balls. Unlike so-called 'migrant' communities, this form of social activity never loomed large in her family or other anglo families she knew, even though her mother wistfully recalled that her husband—and her late father (Nanna's husband)—had been 'beautiful dancers' in their time. When he wasn't at Lodge her own Dad occasionally danced at weddings, but with other women; not with her Mum, who she couldn't remember wearing flowers in her hair—just helping in the kitchen with an obligatory corsage pinned to her chest.

-

She soon learned dancing wasn't the main activity at weddings, engagements and twenty-firsts; drinking assumed priority, with eating a close second. Men bonded around the barrel at one end of a hall, with women at the orchestra end, all dolled up and dying to be asked. Kids, of course, always went silly around music so women at least got to dance with their own or other people's children. As a child attending these all too few occasions, she believed this arrangement was to protect all those pristine corsages—anaemic orchids, usually, with a sprig of asparagus fern—from being crushed into heaving bosoms by sweating, lumbering and often 'legless' men.

-

Her only other memory of childhood dancing was a brief career on the stage—about an hour—at her one and only ballet class at the Holmesglen Housing Commission factory. 'Just follow the others, dear,' the teacher kindly instructed a bewildered three-year-old who didn't understand the well-meaning adult laughter and cried all the way home. She never went back.

-

At least the Plymouth Brethren Sunday School wouldn't subject her to that kind of experience. Dancing and music were the Devil's work and the only upright organ in that gothic world of Gethsemane and gloom had a keyboard attached—and even this was hideously out of tune. Glamour and dance might be summoning her from the family album, but it strained against an apocalyptic hold by the horrors of hellfire. Because her parents weren't religious, they didn't realise until almost too late the effect this was having on their twelve-year-old daughter, by now sermonising from school desktops, presciently signalling a future teaching career. Subsequently, her enforced relocation to a local Baptist church only re-confirmed the knowledge that sex was dangerous because it might lead to dancing.

-

Throughout this period, the photograph of her Nanna continued to intrigue her and in retrospect, it seemed possible that something of that dancing 'grandmother abroad' was channelled into her own personality—or at least provided a rationale for the wanderlust infecting most of her adult life. Whatever the connection, imagined or real, those flowers behind her grandmother's ear indelibly stamped the fragrance of Oceania, travel and tropical exotica into the granddaughter's DNA.

-

Nearly forty years later, in (Western) Samoa, there would be a superabundance of leis and grass skirts to contend with. And here, her experience of dance in its widest possible interpretation would, she liked to imagine, approximate the pleasures her grandmother may have known somewhere on a cruise ship in unknown waters so many years before.

Disembodying the Pacific

-

In 1996 the new academic grandmother arrived in Apia via Nadi for the VIIth Festival of Pacific Arts without, she believed, any yearnings for paradise, either childhood visions of tropical islands or the other, airy-fairy fundamentalist kind. Having withstood a decade of Sundays upholding religious rectitude and bodily revulsion, there had to be a more attractive paradise than the shivering domain of the freshly baptised. Their abject nakedness was, ironically, horrifyingly evident under clammy and clinging white gowns, offering an unpleasantly prurient kind of exposure to their fellow believers living in physical self-denial. This was not for her. By sixteen, she had escaped baptism, rejected religion, got a life and went dancing.

-

Later, after completing a number of university degrees as a mature-aged student-solo-mum on the 'Deserted Wives Pension', any residual fantasies of Oceania were mostly excised—or exorcised. Now a middle-aged matron, she was, after all, shaped to some degree by post-structural and postcolonial discourses, even though some colleagues would describe her theoretical position as 'irregular'. This irregularity had involved regular travelling throughout New Zealand and Southeast Asia, rather than the northern hemisphere. By the 1990s she took up an 'appropriate' stance towards Oceanic studies but, having been effectively inoculated early on against excesses of dogma, her engagement stopped short of missionary zeal. There was always room for the unexpected.

-

More importantly, she had recently assumed a status in life that conferred new and serious responsibilities—at least on Mondays. With grandmotherly decorum and accompanied by a moderate amount of post-colonial baggage, she was determined to skirt those crashing Pacific clichés of surf, sensuality and garments of grass. While for most Australian academics the Oceanic region represented little more than 'coconuts, cannibals and cruise ships', hadn't she recently examined a New Zealand thesis on the 'dusky maiden' syndrome as it pertained to the Tahitian pareu? And wasn't she keenly aware of exploitative and tacky tourism in Pasifika?

-

Indeed, she intended that her visit to this renowned arts festival would uncover deeper truths about a less sunny, more realistic, and highly specific Pacific. There would be issues and problematics to be discovered by diligent cross-cultural observation—with some time factored in for enjoyment—of a culturally-sensitive kind. What floated above those sensuous Samoan lagoons was not just fragrant frangipani but mosquitoes, histories of colonial exploitation, AIDS and diabetes, (un-utterable) incidences of incest and galloping government corruption. And then there were overfed pastors and their over-abundant churches gouging impoverished parishioners, with each family's Sunday tithes broadcast across the national airwaves. Oh yes, she knew about 'The Church'.

-

With all these issues to be addressed, the clichés of lapping waters, rolling hips and swaying palm tree beaches just wouldn't wash. Instead, fluid identities and porous boundaries would, hopefully, provide more appropriate metaphors for cross-cultural understanding in this part of the world. Perhaps more to the point, there wasn't much choice; she was an ageing and somewhat overweight Nanna with painful arthritis and limited mobility in her left hip and not exactly in sync with the languid and sexually alluring rhythms of Polynesian life—those very qualities that beleaguered the islands' colonial histories.

Figure 9. Apia, 1996, Anon.

Figure 9. Apia, 1996, Anon.

Figure 10. The grass skirt seller, Apia, 1996, Anon. | |

|

-

As she anticipated, difficult issues were all waiting to be explored and on arrival she assumed a benign kind of positionality towards this large cultural event. Undoubtedly, an older single but non-widowed western woman occupied an awkward kind of identity in Samoa, which the politics of hibiscus did not accommodate. Women were either single and available, or married and unavailable. The category of divorced and available elicited outbursts of embarrassed giggling, so divorced and unavailable seemed by far the most appropriate option, even if she was totally confused as to where exactly in her hair the floral adornment should go. Anyway, she didn't understand her irrational desire to wear hibiscus, having consigned that shipboard photo to the depths of her unconscious. Furthermore, these floral codes caused her professional self to wonder how the gender-bending fa'a fa'fine signalled their status; perhaps the hibiscus became a floating signifier?

-

Meanwhile, for the first day in Apia her grandma's brag book proved remarkably useful; it allowed her to connect as a slightly-less crass tourist and more as a grandmother-auntie-teacher figure—an endearing Mother Hubbard, she imagined, with a disposable intellectual edge. A Woman of Substance. What she didn't count on was the overwhelming impact of those thousands of visitors. Coming mostly from other Pacific nations, they swamped Samoa's small islands with music, a certain amount of organisational tension, and non-stop dancing. This was interrupted only by serious cross-cultural conflict between ultra-religious Samoans attacking barely clad PNG dancers. Everywhere, unexpectedly, amidst relentless drum rhythms, dance became unavoidable. Like an outbreak of St Vitus, multitudes of swaying torsos and swirling hips sashayed across the island beneath an assortment of sarongs, fine mats and siapo, not to mention swishing grass skirts of every possible variety; raffia, flax, pandanus and plastic—from the Solomons and Rapa Nui to French Polynesia with its skinny contingent of wanna-be Las Vegas showgirls in polyester pareus. But the real place to be was watching the 'grass-skirted'—or perhaps, 'ti leaf' adorned—Samoan warriors perform their fire dance. Just in case…

-

Nothing had quite prepared her for this heart-stopping experience of dance from which there was no escape. She too was expected to join in like everyone else which was a cause for serious anxiety; she wanted to dance and sit cross-legged, but was handicapped by fear, less about the discomfort of her unyielding hip than how unattractive crippledom appeared far away from the safety of equal opportunity legislation. Nevertheless, she enjoyed the all-pervading sense of hedonism, the relaxed rhythms and the utter irreverence for time schedules, while inwardly continuing to struggle; she was determined to get beyond the islands' gorgeousness and make deeper connections.

-

To her utter astonishment, this happened, but not quite as she had anticipated. It was probably something to do with the red hibiscus pinned behind her ear that set off her loose white linen dress so well—and also set off another train of unexpected events. Eventually, despite all her best efforts at resistance, she would succumb to becoming that creature so despised within her own milieu—a western tourist having way too much fun in an exotic location.

-

Meanwhile she was doing her best to maintain a sensible composure. The beautiful young man to whom her colleagues had introduced her at lunch in the market didn't return to work that day and was soon insisting on carrying her video equipment and assisting her at every turn. 'Why?', she wondered. 'Did he pity her?' 'Would he run off with the camera or demand payment?' A fiercely independent person, she was at a loss; he was clearly offended by her repeated refusals of help as she determinedly limped across town regardless, under the weight of heavy photographic gear. But he would not be deterred. Like many Samoans, explained a local colleague, he was showing kindness to a visitor and respect for age. And even more surprisingly, he seemed riveted by her baby photos. In eventually acceding to the inevitable, she recognised the embarrassingly 'colonial' scenario of white mistress/black servant that would outwardly define their relationship, whatever the reality. A somewhat tragic image for an older white woman, this inevitably brought forth disdain and sniggering from the more sanctimoniously smug of her Australian academic and 'art worker' colleagues. Try as she may, she was now occupying an ideologically dodgy position.

-

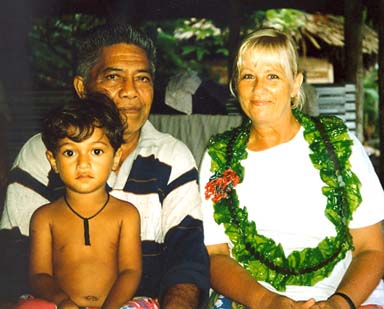

As the days passed, the beautiful young man took to waiting outside her hotel every morning, eager to hear more stories about her family, admire even more photos of her cute little granddaughter, practise his English and teach his 'adopted grandmother' some Samoan words. Or so she thought. When he escorted her to the festival village and bought a colourful little grass skirt for her 'grandbaby', she didn't let on she had already purchased (a more 'authentic') one the day before. She graciously accepted the gift, conscious of his dire financial situation, that didn't, however, prevent him being AWOL from work for an entire fortnight. The festival and its guests' welfare were obviously taken seriously by Samoan people.

-

After a few days, he took her to his village in Savai'i, where she was received with great honour and surprising open-ness by his blended family, even without sitting cross-legged like everyone else. This seemed to delight the children and the chooks who crowed with hilarity. And to her delight these people, dozens of them, couldn't get enough of the baby and family photos. Even a suitable match for the palagi infant was suggested with the youngest grandchild, a beautiful two year old boy, when she returned to the village two years later. He was named after his family?s island, Savai?i.

Figure 11. Savai'i and his grandfather, 1998, Anon.

Figure 12. Savai'i, Samoa, birthday party, Anon.

-

In the village she was also confronted with the rudimentary protocols of gifting, obligation and hierarchy while inhaling fragrant frangipani and hymn singing, her eyes full to the brim with turquoise lagoons, palms fronds and magenta bougainvillea. The senses would be denied no longer and the whiter than white Sundays in church—and across the whole island—appeared exquisite, even to an agnostic and hopelessly-lapsed Baptist.

-

This was not, of course, paradise and there were capital 'I' issues underlying this apparent idyll. She didn't like the child beatings but was impressed with the way small children were taught to be useful and the fact that teachers and other mothers took their babies to work. The minister next door was indeed large and sleek and yes, an obligatory visit demanded donations of enormous tins of spam and fish-the-west-rejects. His clerical position was, surprisingly and to her dismay, seriously aspired to by local youth. Whether religiously inclined or not, they hung out at the local bible college, playing reggae, teasing the fa' a fa'fine and talking dirty. How else do these boys obtain a Mercedes or even a decent income in the islands? She also discovered the traditional Sunday umu oven of locally-harvested food is usually followed by six days of greasy mutton flaps, cold tinned spaghetti and instant noodles, the legendary diabetes diet of Polynesia. And everyone laughed at her idea of drinking coconut juice—everywhere on the islands. But the hospitality was warm and generous, she wasn't allowed to go hungry or lonely and these relations would be reciprocated and maintained over the next few years.

Figure 13. Waterfall, Savai'i, Samoa, 1998, Anon.

-

It was in the village that the kids got her dancing and laughing amidst abundant flowers and leis made with cellophane and coins. As gawky as she must have looked, there was no way out of this exuberance and ultimately, she had to admit, it felt good to master the Macarena and a few local dance movements, even if colonial mimicry was very much at play. Suitably attired, she soon found she could once again enjoy swimming, walk without discomfort and clamber up small waterfalls. While this improved health might be explained by the humid climate alone, it also seemed to have something to do with a culture embedded in bodily awareness, in particular, various forms of dancing where age, body shape, sexuality and disability matter much less—as long as everyone is decently clad.

-

She returned home with not only a suntan, some excellent video-teaching resources and material for critical reviews of the Festival; she was five kilograms lighter, with a smile on her face and a noticeable spring in her step. Just like every other Pacific tourist. While she no longer felt ashamed of her awakened senses, all this wellbeing was toned down once back at work. 'How was Samoa?', colleagues would enquire, patronisingly. 'Well, you know', she had learnt to reply, soberly, 'the Festival represents a significant unifying experience for Pacific identities but there are real issues over there and I'm not convinced that Bhabha, Butler or Baudrillard provide a useful…'. By which time they had walked away. Her students, on the other hand, were hungry for more and her approach to research had changed.

-

Mondays were a different story altogether. Once research-free, these days had become even more exciting when filled with the unconditional love that only grandparents and grandchildren understand. And now these days assumed a particular Oceanic overlay. Once the grass skirts were unwrapped by the tiny girl and Samoan music was switched on, an important ritual was set in train every time the child visited for at least the next few years. Every Monday, as soon as they returned from handover with her mum, and before anything else could happen, the granddaughter would reach up excitedly for the straw skirts and their 'accessories'—hand-made leis, fans and mats from the village, all now dangling from hallway hooks. Solemnly draping herself in these garments, the wide-eyed child then pointed up to the cassette deck in the lounge room (on a cupboard shelf inside a converted boat), using most of her newly acquired vocabulary: 'Nanna, Samoa!' And dressing her grandmother in the other skirt, this tiny person insisted: 'dancin', dancin' for all, including the grandmother's large black and white Angel Cat (who, strangely, doted on the child in a most unfeline manner); Pussy, the little girl's beloved ginger soft toy, and various other disreputable teddy objects. Everyone took turns with the skirts and nothing escaped adornment with flowers gathered from the garden.

Figures 14, 15 and 16. The skirt, 1998; The skirt 1998; Home one Monday, 1998, photographer P. Zeplin.

Figures 14, 15 and 16. The skirt, 1998; The skirt 1998; Home one Monday, 1998, photographer P. Zeplin.

-

Although a private performance ritual, the most significant aspect for the grandmother was the dancing. At first, she had bent down to gently explain: 'Sorry, Darling. Nanna can't dance. She's got a sore leg,' an explanation trotted out for years to avoid public embarrassment. But of course this idea was utterly incomprehensible to a fifteen-month-old child who hadn't yet acquired the word 'cripple' in her vocabulary—and besides, the grandmother had been able to dance in Samoa. There was nothing for it, then, but to do as bidden.

-

In swaying to the Polynesian, Reggae and Latin rhythms of a compilation 'Island' tape, here there was no embarrassment about clumsiness, fear of falling or fear of failing. There was plenty of lurching and falling about but this was accompanied by giggles and gurgles of sheer joy at the exhilaration of dancing secretly and badly amongst what looked like tourist trash. Occasionally, visitors joined in, to the utter bewilderment of meter readers and Jehovah's Witness missionaries knocking on the front door.

-

So every Monday the tiny tot and her besotted grandparent played, shopped, dined, laughed, learned, told stories and drew in their precious hours together, but best of all they always danced, during and way beyond this period of child-minding duties. The pair might have done this anyway, without the catalyst of Samoa's festival but it's doubtful whether the dancing rituals would have been so religiously observed. By the time kindergarten beckoned for the granddaughter, a hip replacement was beckoning for the grandmother, surgery which healed remarkably quickly thanks to strengthened 'dance' muscles. Fourteen years and three hip replacements later, both grandmother and granddaughter are still dancing, although not together these days. And like her grandmother before her, the newer grandmother is still travelling—throughout Oceania. She is still hoping her teenage granddaughter will accompany her there one day.

Figures 17 and 18. The skirt, 1998, photographer, P. Zeplin.

Figure 19. The skirt, 1998, photographer, P. Zeplin.

Post Script

-

The old shipboard photograph recently resurfaced in a long lost box and she was astonished and disappointed to see there was, in fact, no lei around her grandmother's neck—just flowers in her hair. Then a relative in Perth suggested this shot may not have been taken on board ship. We can never know the precise circumstances of those exotic accessories or their setting but what is undeniable is that the senior woman was, in her day, hot to trot.

-

It has been said that memories are like islands[1] and we can't precisely navigate the exact circumstances surrounding them. Any connections, therefore, between the two grandmothers separated by so much space and time could only be inferred though visual fragments and unreliable family memories. Apparently shared predilections for independence, travel and dance might only be projections on the part of the granddaughter-recently-become-grandmother craving a more complete family lineage through a grandmother-she hardly-knew but with whom she desperately wanted to identify. As far as she knew, her Nanna never visited the Pacific but it was in Samoa that those mysterious genealogical connections—imagined or otherwise—were so powerfully called up.

-

Her subsequent associations with this and other island cultures thus became more than the chance of a dance or sites for 'colonisation' by the latest continental theories. A noticeable shift in the way she approached her life and career had taken place. A greater sense of embodied knowledge and play began to nudge sideways—like the hula—those puritanical structures that go largely unchallenged in western institutions, whether these are in the form of ridiculous regulations or rigid theories 'about' indeterminacy and flow.

-

Whether or not Oceanic cultures can be characterised by this sense of openness, fluidity and bodily expression or whether this represents a romantic stereotype experienced on a quasi-research visit remains open to debate. It is a debate she trusts will be conducted in the Pacific as well as in foreign universities.

Figure 20. Dancing in the garden, 1998, photographer, P. Zeplin.

-

Little children, wherever they live, already know this way of being and they teach it to their grandparents and anyone else willing to learn. Her own grandmother undoubtedly had this knowledge but was unable to share it with her oldest granddaughter. Hopefully, a small grass skirt, a few flowers and a rendezvous in Samoa with her grandmother's spirit have helped restore an important part of her family's heritage.

-

As she was reflecting on this cyclical turn of events, she began to take down the little grass skirt and pack it away for 'later'. And then she stopped, placed it back up on the hook and again smiled to herself. She now had a little grandson.

Endnote

[1] Steven Bowers, 'ArtistsSpeak,' in Art, Architecture & Design, University of South Australia, 9 March 2010.

|