Transmission of Trauma, Identification and Haunting:

A Ghost Story of Hiroshima

Naono Akiko

Atom bomb drawings by survivors

-

Several winters back during fieldwork in Hiroshima, I felt drawn to the 'Atom bomb drawings by survivors' (hereinafter, 'A-bomb drawings'). As many as 2,225 drawings were produced by 758 survivors in 1974 and 1975 and subsequently donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.[1] About thirty of them are on display and available to visitors on display in an annually organised exhibition in the special room of the Museum. The remainder are being stored in boxes in the basement of the Museum and I spent several months commuting to the basement of the Museum to record all of the drawings. I took a photo of each one with a digital camera, printed it, developed a database, and visited about sixty of the artists.[2]

-

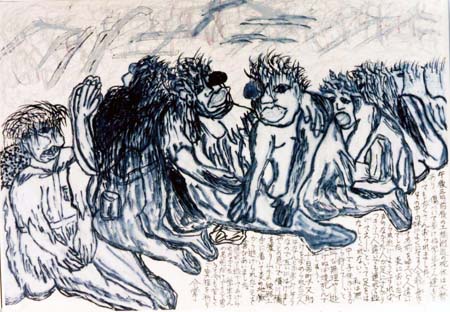

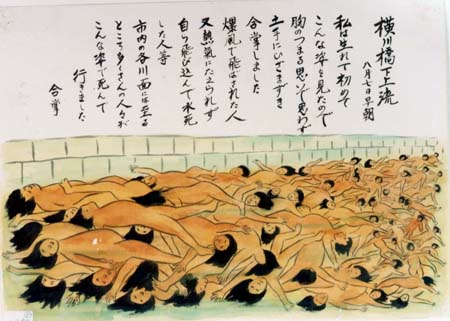

Continuously encountering memories of A-bomb experiences, whether through textual or visual representations or oral testimonials, takes considerable physical and emotional energy. Sometimes the content is so brutal and horrific that my chest seizes up. I was often overwhelmed by the extent of survivors' lasting pain and sorrow for having lost their loved ones and having outlived them. A-bomb drawings visually render memories of the scenes survivors witnessed immediately after the bombing and, precisely as visual images, they seem to have the power to etch themselves into viewers' memories, as if they experience the scene vicariously. As I looked time and again at the 2,000-plus images, I began to feel the gaze turned back by the human figures in the drawings.

Figure 1. By Ariyoshi Kosada. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 1. By Ariyoshi Kosada. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 2. By Saiki Toshiko. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 2. By Saiki Toshiko. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

|

-

Some depicted scenes began to appear repeatedly in my dreams, not unlike the 'dreams of traumatic neurotics' Freud spoke of in 'Beyond the pleasure principle.'[3] Sometimes I was the one trapped in the flames.

Figure 3. By Michitsuji Yoshiko. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 3. By Michitsuji Yoshiko. Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 4. By Matsumura Chiyeko, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 4. By Matsumura Chiyeko, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

|

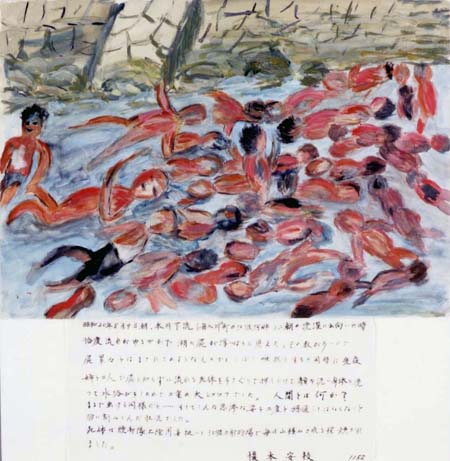

Occasionally I felt disoriented, pursued by the stench of death, and even struck by the 'flashbacks' of corpses floating, as I walked along the river of Hiroshima.

Figure 5. By Nakano Ken'ichi, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 5. By Nakano Ken'ichi, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Figure 6. By Enomoto Yoshiye, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Figure 6. By Enomoto Yoshiye, Source: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

|

I was captured by the traumatic force of the drawings, the visual representation of the memories of original trauma, as if the force of other's trauma was being transmitted to my body.

-

This kind of story is usually written off as mere anecdotes of the fieldwork and not given serious consideration in academic endeavour, especially in the filed of sociology, despite its claim to study 'social worlds.' But it is not rare that you are drawn into the force of trauma in inquiring into the traumatic experience of others, whether through direct interviews or archival research of documents and visual images. In clinical settings, the phenomenon of 'transmission of trauma' is often understood in terms of 'transference/counter-transference,' 'secondary, or vicarious, trauma' or 'compassion fatigue.'[4] In Holocaust Studies, many have discussed the transmission of trauma in terms of generational inheritance of memories from the first to the second generation.[5] Among them, Marianne Hirsch's works on 'postmemory,' in particular, will be analysed in relation to Toni Morrison's 'rememory' and 'ghost' in later section of this paper.

-

With these bodies of work in mind, I will first review the psychoanalytically informed writings of Derek Hook, Dominick LaCapra and Robert J. Lifton, and then Freud's theory of identification, in an attempt to make sense of my affective responses during the fieldwork, especially to the A-bomb drawings. In reading the drawings in particular, I will also briefly take a look at Jill Bennett's work on art and affect, before moving to Hirsch's and Morrison's theories of memory and transmission of trauma. Finally, I will introduce the sociologically-informed theory of haunting proposed by Avery Gordon, in order to bring forth an emancipatory possibility in transmission of trauma. In this essay, I want to develop different vocabularies to talk about the transmission of trauma by paying attention to what is often neglected or written out from sociologists' field notes: uncanny encounters with ghosts.

Uncanny interpellation and the subjectivity of the monumental space

-

Benedict Anderson, in the opening section of his second chapter in Imagined Communities, observes the tombs of Unknown Soldiers being 'saturated with ghostly national imaginings' (emphasis in original);[6] National monuments and memorials similarly seem to invite the visitors to sense the presence of those to whom these objects are dedicated and who they memorialise. The ghostly power of the monuments and memorials is sometimes so strong that it instigates the visiting subject to act on behalf of the ones being memorialised. Such was the case of white supremacist Barend Strydom in South Africa, who shot dozens of black men and women at Strijdom Square in 1988.[7]

-

Derek Hook turns to Freudian psychoanalysis to make sense of Strydom's racist attack in the monumental space of Strijdom Square, by paying particular attention to 'the relation between the subjectivity of the individual political actor and the ideological force of the monumental site.'[8] Hook goes on to theorise the psychic investments of an individual in the 'ideological aura of a monumental space,'[9] in this case, Strydom's investment in the racist ideology of Apartheid. More specifically, Hook proposes to develop a provocative notion of 'subjectivity of place.' This concept has nothing to do with occultism; subjectivity of place is imaginary, a 'function of the "intersubjectivity" of the subject and their involvement with the imagined consciousness of the place.'[10] To imagine subjectivity of place or object, it is crucial that a given ideology is embodied in it, or given a figurative form. Applying the Freudian concept of 'uncanny,' Hook considers embodiment as 'a kind of technology of affects,' which imbues place and/or object with a 'psychologized presence of identity.'[11]

-

Monuments with a human form in particular are effective as a technology of affects, for they can produce uncanny feelings in the present subjects and in so doing mobilise their subjectivity and corporeality. Among Freud's examples of the uncanny, Hook gives a particular importance to the case of the 'embodied absence and disembodied presence,' which Freud borrows from E. Jentsch: this manifests as 'doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate.'[12] Hook insists that human-figured monuments cause 'ontological anxieties about the status of the object, and more particularly, anxieties about its status as human,' since they take on, 'at a moment of ontological error' 'a psychological presence, an imagined subjectivity.'[13]

-

Presented with the monument's disembodied presence, or wandering soul without the body, that produces a heightened sense of ontological dissonance, an individual at the monumental site is hailed to provide his or her corporeality to repair its disturbing affects. In the case of Strijdom Square, Barend Strydom gave his corporeality to the symbolic statue of Apartheid ideology and acted out racial violence. At the same time, while the human-figured monument appears animate, it is merely an object and devoid of soul. Presented with the embodied absence, the subjectivity of an individual is hailed to fill the ontological gap between the soul and the body.

The uncanny, according to Freud, presents a 'regression to a time when the ego had not yet marked itself off sharply from the external world and from other people.'[14] This 'momentary lack of ego-definition or ego-separation'[15] begs the subjects to resolve the ontological disjuncture by identifying with the uncanny object. In other words, ego-disturbance produced by the uncanny induces subject-object identification, a kind of making of the subject who acts out the ideology the object embodies.

Identification in Hiroshima's memorial space

-

Hook's analysis of the monumental space gives us a new way to consider transmission of trauma as ego-affects of the uncanny, which trigger the subject's psychic involvement in places marked by trauma or objects representing trauma. Identification induced by these affects can be theorised as a psychic mechanism of transmission of trauma from the objects which embody traumatic events and/or those consumed by them.

-

Before inquiring into various mechanisms of identification in relation to transmission of trauma any further, let us turn back to Hiroshima's memorial space. Although they evoke different sentiments than the Strijdom monument, memorials at Hiroshima's Peace Park and artefacts displayed at the Peace Memorial Museum can be classified as the uncanny, as they appear to have the sort of subjectivity Hook speaks of. Not only human-figured memorials, but also remains of the objects that used to belong to those destroyed by the bomb, such as a broken wrist watch and a burnt school uniform, evoke a sense of uncanniness, as they appear to embody the souls of those violently killed by the atomic bombing who have been left behind, unclaimed by anyone.[16] Freud points out that the uncanny is felt in the highest degree in relation to the return of the dead, spirits and ghosts.[17] They make us feel most uncanny, causing massive anxiety to the subject and disturbing the ego, since they are doubly out of place: without body and out of natural time.[18]

-

Among the visitors to Hiroshima's memorial space, those who more or less believe in the presence of souls of the deceased are most vulnerable to the psychical force of the uncanny, since they are very likely to sense the ontological dissonance between the body and the soul of which Hook speaks. Having given subjectivity to the objects presented in the memorial space, are we inevitably led to act out the ideology embodied in these objects, as in the case of Strydom?

-

Hiroshima's memorial space provides various means, other than acting-out, to resolve, or at least quiet down, the unsettling affects induced by the uncanny objects. The most widely adopted way is an attempt to quiet the wandering souls of those killed by the bomb by putting hands together in prayer in front of the Cenotaph of the Victims, pledging, 'Let all souls of the victims rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil.'[19] Another common way to resolve ego-disturbance is to identify with the victims of Hiroshima, which can lead to acting-out, albeit differently from Strydom.

-

Identification as a psychic reaction of visiting subjects is widely observed in Hiroshima's memorial space, which has been largely produced as a discursive space of national identification. Memories of the atom-bombing in Japan have been produced as a 'national tragedy,' which was firmly set in place as a historical-cultural construction in the mid-1950s.[20] As such, it has enabled many Japanese to assume the subject-position of the victims of nuclear attacks and as 'victims of the Asia Pacific War.'

-

Furthermore, even those who cannot identify with the atom-bomb victims on the basis of nationality can easily relate to the familial narratives, especially of 'unbroken tie between mother and a child' and an 'innocent child victim,' and thereby empathise with or even identify with the victim. Put another way, familial narratives provide a space of identification for most of the visiting subjects to the memorial space. This narrative strategy is often employed at various memorial sites of violence and tragedy, including museums, because anybody can easily identify with the victim regardless of gender, ethnic, or national identity, so long as they participate in the ideology of the modern family.

-

Many of those who visit Hiroshima's memorial space identify with the victims, whether through national remembrance or familial narratives, and give their corporeality to, or 'act out,' the ideology of peace (and in recent years, of reconciliation). Many do so, for example, simply by praying for peace and others more actively by participating in anti-nuclear activism and peace-education programs. This may be a welcome development for the atom-bomb victims, whose 'unwavering hope' is presented as the 'abolition of nuclear weapons and realisation of lasting world peace.'[21] Yet, identification with the victims and acting-out of the ideology of peace could become a dangerous, if not violent, act, when carried out without self-reflexivity.

-

In the process of identification, the object (in this case, the victims of Hiroshima) can be replaced by the subject. The object to be identified with is subsumed under and incorporated into the identifying subject, which in turn assumes the position of the identified (in this case, the victims). In the process of identification, therefore, the otherness of the identified other becomes hardly recognisable. Furthermore, the social relations of power between the identifying subject and the identified victims are obscured, precisely because they are presented as identical in this process.

-

The obscuring of social relations of power through identification occurs mainly in two areas, both of which are closely connected to amnesia. First, it is produced through the ideology of 'peace' in Hiroshima's memorial space, which is overwhelmingly articulated through the ideology of the nation-state. It positions the atom-bomb victims exclusively as 'Japanese,' while subjugating memories of the non-Japanese atom-bomb victims and particularly those subjected to Japanese colonial violence.[22] Furthermore, even when it is articulated through 'anti-nuclear universalism,'[23] the ideology of peace often de-historicises and de-politicises the events leading up to the atomic bombing and thereafter, which include the history of colonialism, and thereby conceals the history of state violence committed by both the United States and Japan.[24] Second and closely connected to the first one, identification with the victims produces and is enabled by amnesia in Japanese society of the history of prejudice and discrimination directed at the survivors. Identification, in other words, works as a defence mechanism for the visitors to Hiroshima's memorial space, while perpetuating the wounds inflicted upon the victims of the atom-bombing.

Identification and transmission of trauma

-

Concern over the danger of identification is shared by Dominick LaCapra, a historian who has endeavoured to bring psychoanalysis to the field of historiography. LaCapra delineates identification as the psychic mechanism of transmission of trauma and cautions against complete identification with the victim on ethical grounds. So-called 'contagiousness of trauma' according to LaCapra, is a phenomenon of 'transference' in the psychoanalytic term. Understanding transference more broadly than Freud and fundamentally as a process of repetition, LaCapra forcefully argues that transference occurs not only between people, but also 'in one's relationship to the object of the study itself.'[25]

-

While transferential relations are neither preventable nor easily manageable, especially with 'the most traumatic, affectively charged, or 'cathected' issues,'[26] LaCapra stresses that they must be worked through, instead of being acted out. When you identify with the victim of trauma in 'an uncritical manner,' LaCapra warns, you tend to act-out, or repeat, the victim's trauma.[27] In this process of projective and/or incorporative identification, you may 're-experience post-traumatic symptoms of events (such as the Holocaust or slavery) one has never lived through.'[28] Infection by other's trauma is possible not only for clinical practitioners and family members who are in close contact with the traumatised victims, but also for 'those who work closely with texts or films conveying their experience.'[29]

-

The process of acting out may not be completely avoidable, but LaCapra stresses the importance of efforts to respect the otherness of the other, and not to own other's trauma through identification. Thus, he proposes 'empathetic unsettlement' as an alternative response to identification. LaCapra on one hand acknowledges the importance of affective responses, such as empathy and compassion, to traumatised victims, because they limit objectification of the victims and the defence of distancing ourselves from the traumatic event. On the other hand, he urges us to recognise the difference between the victim and ourselves and to avoid appropriating the victim's trauma by allowing ourselves to be 'unsettled.' Unsettlement prevents easy closure and smoothing out of disruptive and unnerving elements in the memories of traumatic events, which often results in 'harmonizing or spiritually uplifting accounts of extreme events from which we attempt to derive reassurance or a benefit.'[30]

Dangerous identification

-

Identification may be an unavoidable psychic response to the infectious power of historical trauma, as LaCapra suggests. As such, it presents the danger of taking over others' trauma and even furthering their trauma. But identification also poses a great threat to those who identify with the victims, as suggested by Robert J. Lifton, a psychoanalyst who pioneered the study of the psychic effects of atom-bombing on the survivors of Hiroshima.[31]

-

Researching Hiroshima survivors in the early 1960s, Lifton was struck by the 'imprint of death'[32] covering survivors' psyches and even the community of Hiroshima as a whole. Lifton lists three main factors contributing to survivors' 'death-dominated life'[33]: the 'overwhelming encounter with death'[34] in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, fear of the lasting effects of radiation that leaves on the survivors the 'permanent taint of death,'[35] and the building up of nuclear arsenals. Closely connecting the 'death imprint' of the survivors with their guilt over having survived, Lifton observes a tendency in the survivors to feel impelled to identify themselves with the dead, who they feel were 'maximally wronged.'[36] Calling this 'identification guilt' Lifton points to the importance of the gaze of the dead directed at the survivors, which is being internalised by the survivors themselves and invokes a sense of guilt.

The basic psychological process taking place is the survivor's identification with the owners of the accusing eyes as human beings like him [sic] for whom he is responsible, his internalisation of what he imagines to be their judgment of him, which in turn results in his 'seeing himself' as one who has stolen life from them.[37]

-

This 'identification guilt' does not stop with the survivors: Lifton provocatively claims that it extends to the whole world. Because the accusing gaze comes from anonymous dead, it seems to come from the '"all-seeing eye" of an unknown deity, or the "evil eye" of an equally obscure malevolent power.'[38] 'Identification guilt,' like radioactive materials of the nuclear bomb, according to Lifton, 'radiates outward' from those destroyed by the bomb to the survivors to 'ordinary Japanese to the rest of the world.'[39] Each of these groups 'internalize[s] the suffering of,' and thereby feels guilty toward, the one that is 'one step closer than itself to the core' of death.[40]

-

In addition to the guilt associated with identification with the survivors, Lifton observes a strong sense of 'contagion anxiety' in those closely involved with the survivors.[41] On one hand, they feel guilty toward the survivors, with whom they identify by internalising their suffering. That same person, on the other hand, feels anxious about being contaminated by the 'death taint' of the survivors. Combining 'identification guilt with contagion anxiety,' those close to the survivors, therefore, are 'torn by conflicting needs to merge with the survivor in total compassion, and to flee from him [sic] in a confused state of guilt and resentment.'[42]

Contagious identification and infectious trauma

-

Both LaCapra and Lifton address the danger of identification with the victim of trauma, but while LaCapra warns the identifying subject not to appropriate other's trauma, Lifton turns more to the risk posed to the identifying subject of being consumed by the other's trauma. Their difference in emphasis seems to parallel two directions in Freudian theory of identification.

-

Three types of identification are discussed in Freud's paper entitled 'Group psychology and the analysis of the ego.' Presenting identification as 'the earliest expression of an emotional tie with another person,'[43] Freud first discusses the case of a small boy identifying with his father, who is his ideal figure. This pre-Oedipal stage of identification, or primary identification, sets up a stage for 'the normal Oedipus complex'[44] to develop, where the little boy longs for his mother and wishes to replace his father. Identification, according to Freud, is, therefore, 'ambivalent' from this very first stage:

it can turn into an expression of tenderness as easily as into a wish for someone's removal. It behaves like a derivative of the first, oral phase of the organization of the libido, in which the object that we long for and prize is assimilated by eating and is in that way annihilated as such.[45]

Here, Freud represents the subject's oral digestion of the other as a mechanism of identification. Identification, in other words, can be conceptualised as a violent psychic act, since it involves annihilating the other, for whom the identifying subject longs, through oral incorporation. In his discussion of identification with the trauma victims, LaCapra seems to focus on this aspect of identification. But identification as a vulnerable process for the identifying subject is also discussed by Freud, albeit briefly.

-

As a third 'particularly frequent and important case of symptom formation,' Freud turns to a hypothetical case of hysteria being spread from one girl to other girls in a boarding school by 'mental infection.'[46] The mechanism of 'mental infection' is, according to Freud, that of 'identification based upon the possibility or desire of putting oneself in the same situation.'[47] One ego finds a similarity with another on one point and this 'coincidence between the two egos' (emphasis added)[48] constructs identification through the means of symptoms.

-

Diana Fuss explains that in the process of identification through mental infection, a passive subject is infiltrated by 'an object not of its choosing.'[49] In other words, the identifying subject is being seized by the other, as opposed to seizing the other in incorporative identification. Put another way, identification is not simply an active process of the subject devouring the other, but also a process of the vulnerable subject being affected by the other. In fact, in their discussions of identification as acting out the ideology or symptoms of the other, neither Hook nor LaCapra refers to Freud's underdeveloped concept of contagious identification.[50] While he does not refer to it either, Lifton's discussion of 'contagion anxiety' comes closer to this aspect of identification. Transmission of trauma can, then, be conceptualised not just as primary or incorporative identification as Hook and LaCapra suggest, but also as contagious identification, where the subject is being infected by the power of trauma affecting the objects of identification, even against his or her will.

A-bomb drawings and identification

-

Now, let us go back to my experience of being captured by the power of traumatic memory through the A-bomb drawings. To read visual images regarding traumatic events, such as the A-bomb drawings, a theory of art and affect developed by Jill Bennett is instructive. Engaging with Gilles Deleuze's theory on affect and French poet Charlotte Delbo's concepts of 'common memory' and 'sense memory,' Bennett provocatively proposes a possibility of bodily transmission of traumatic affect through the medium of artworks and visual images.[51] 'The imagery of traumatic memory,' Bennett contends, does not simply represent a traumatic past, but 'enact[s] the state or experience of posttraumatic memory.'[52] In other words, visual arts representing trauma engage the viewers affectively by producing traumatic effects.

-

Bennett's arguments can be categorised as a theory of transmission of trauma which considers the affective responses to the visual images of trauma as engendering, or imprinting, a 'secondary trauma.' Yet, Bennett tries to prevent such a reading by carefully differentiating affect from something that is 'precoded by a representational system that enables us to read an image as "about trauma", then to experience it as secondary trauma.'[53] She argues that affective responses induced by images of trauma should, instead, be put to a careful reading. In a Deleuzian spirit, art, Bennett contends, should be understood as an 'embodiment of sensation that stimulates thought,'[54] not something that is automatically decoded according to what it seems at the first glance to represent, in this case, an event of trauma.

-

If I were to follow Bennett's theory of art and affect, the A-bomb drawings can be interpreted as the embodiment of survivors' trauma: not simply the original event, but more the psychic and emotional state of living with traumatic memories thirty years after the event. As such, these drawings catch the viewers' eyes in such a way that they feel as if, even momentarily, they are being transported into the depicted scenes. The drawings also incite the viewers to affectively respond. In previous sections of this paper, such response was delineated as a psychic act of identification, albeit with different implications depending on each theorist. While not all drawings include human figures, the vast majority of them depict injured human figures and dead bodies. These images function as a powerful technology of affects that manifests as the uncanny. Hence they unsettle viewers who are impelled to identify with the victims of Hiroshima.

-

The viewer could, following the theory of uncanny space developed by Hook, identify with the depicted victims and act out the ideology of peace and nation that is represented, not necessarily in the drawings themselves, but in the narrative frameworks that place them in Hiroshima's memorial space. If we take LaCapra's ethical concern in dealing with the other's trauma seriously, the viewers' identifications and reactions might be criticised as appropriating the other's trauma. Lifton provides another way to read the affective response of the viewers as an internalisation of the 'accusing gaze of the dead.' As discussed in the previous section, the gaze of the dead is not only internalised by those who survived the destruction of Hiroshima, but also by everybody living in the nuclear age. Viewers could sense the gaze of human figures in the A-bomb Drawings, such as in Figure 1 and Figure 2, directed at them and develop 'identification guilt.'

-

Finally, if we take Freud's contagious infection as a theoretical frame, intense and involved reactions to the drawings, such as my dreams and 'flashbacks' of the scenes depicted, can be interpreted as symptoms of traumatic neurosis being transmitted through mental infection. Hook, LaCapra, Lifton and Freud offer academic vocabularies which are not sufficient to explain, but nevertheless, enable us to talk about the transmission of trauma within the language of psychoanalysis. In the next section, I will look at another theory that addresses the power of visual media in transmitting trauma through inciting identification.

Postmemory versus rememory

-

Marianne Hirsch proposes a concept of 'postmemory' as a form of memory that is produced as a result of subjects having grown up 'dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation shaped by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.'[55] Postmemory is, in other words, a second-generation remembrance of traumatic events that the subject has not lived through. It is, therefore, a product of intergenerational transmission of trauma.

-

Referring to Jill Bennett's work on art and affect, Hirsch turns to the visual media, especially that of photographs, as a privileged means to generate postmemory, or transmit 'body memory' of trauma. Visual images, according to Hirsch,

do more than to represent scenes and experiences of the past: they can communicate an emotional or bodily experience to us by evoking our own emotional and bodily memories. They produce affect in the viewer, speaking from the body's sensations, rather than speaking of, or representing the past (emphasis in original).[56]

Like LaCapra and Bennett, Hirsch regards identification as an inseparable part of transmission of trauma and addresses its danger.

-

In order to illuminate the danger of identification, Hirsch takes up a concept of 'rememory' introduced in Toni Morrison's widely analysed novel Beloved. The novel presents to us a possibility of 'bumping into a rememory that belongs to somebody else'[57] through the story of Denver, a daughter living in post-Civil War America; she co-experiences her ex-slave mother Sethe's bodily memory of slavery. Sethe killed her baby (Beloved) so that she would not be taken away by the slave-owner. Distinguishing it from more politically-correct postmemory, Hirsch criticises rememory as a form of 'repetition and re-enactment' and 'transposition into the world of the past.'[58] Postmemory, Hirsch emphasises, works through 'indirection and multiple mediation' because its 'connection to its object or source is mediated not through repetition or reenactment but through previous representations that themselves become the objects of projection and recreation.'[59] Rememory 'underscores the deadly risks of intergenerational transmission,'[60] and thereby a subject who experiences rememory over-identifies with the traumatised other and even adopts his or her memories. Postmemory, on the other hand, helps a subject maintain 'an unbridgeable distance separating the participant from the one born after.'[61]

-

I value Hirsch's sincere concern over a type of identification that appropriates the other's trauma and disregards the otherness of the other; however, by enclosing rememory in the realm of individual psyche, Hirsch seems to completely miss the sociality of rememory. As such, her analysis reduces Sethe's rememory to mere symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder; that is to say, her troubled psyche.[62] In such interpretation, the ghostly presence of Sethe's dead child becomes merely a sign of hallucination, not of the 'traces of the past [that] persist in the present.'[63] By not engaging with rememory's sociality, Hirsch forecloses the possibility of paving a way out to her own concern: 'How, particularly, can the bodily memory of the mark be transmitted and received without the violent self-wounding of transposition?'[64]

Sociality of rememory and haunting

Someday you be walking down the road and you hear something or see something going on. So clear. And you think it's you thinking it up. A thought picture. But no. It's when you bump into a rememory that belongs to somebody else. Where I was before I came here, that place is real. It's never going away. Even if the whole farm—every tree and grass blade of it dies. The picture is still there and what's more, if you go there—you who never was there—if you go there and stand in the place where it was, it will happen again; it will be there for you, waiting for you. So, Denver, you can't never go there. Never. Because even though it's all over—over and done with—it's going to always be there waiting for you.[65]

-

Rememory is not a should-be-avoided product of intergenerational transmission of trauma, as Hirsch suggests. It is not Denver's over-identification with her mother that transposes her to a place where her mother used to be. She bumped into a rememory that belongs to somebody else. 'Bumping into' is a form of affective recognition, where traces of past violence that is not 'over and done with' would surface. Rememory, therefore, is a sign not of individual trauma, but of social violence that, as the very concept of 'trauma' suggests, still lingers in the present. That is why Sethe insists that Denver, who was born after the end of institutionalised practice of slavery, will see 'something going on' which is not her 'thinking up'; if she goes to the 'place,' it 'will happen again' for Denver.

-

Taking Morrison's 'rememory' as social memory and haunting, Avery Gordon, a sociologist of culture and affect, endeavours to develop vocabularies to talk about the affective dimensions of ghostly matters in relation, not simply to an individual's troubled psyche, but to social structure and historical forces. Rather than being simply a missing or a dead person, according to Gordon, a ghost is a sign of unresolved violence or injury that appears to be of the past, 'but is nonetheless alive, operating in the present, even if obliquely, even if barely visible.'[66] Gordon insists that ghosts really do appear to us and haunting 'is a generalisable social phenomenon of great import.'[67]

-

Rememory as a social memory of violence enables more socially- and politically-oriented readings of the A-bomb drawings, while attending to their affective power. A reading of the drawings through psychoanalytic theories of Hook, LaCapra, Lifton, and Freud, with help from Bennett, tends to limit itself to the psychic realm of the individual viewer. But if we take the viewer's affective engagement with the drawings as 'bumping into somebody else's rememory,' or being haunted by ghostly presence in the Hiroshima's memorial space, what possibility would emerge?

-

Once encountered, a ghost, according to Gordon, forces us to make notice of 'the living effects, seething and lingering, of what seems over and done with.'[68] But is not.[69] The presence of a ghost, in turn, brings a utopian possibility, if articulated with Walter Benjamin's historical materialism: it is 'a sign to the thinker that there is a chance in the fight for the oppressed past.'[70] Gordon contends that a ghost appears to you because 'the dead or the disappeared or the lost or the invisible'[71] are asking for what they deserve—fulfilment of broken promises and unrealised justice. So, when you are touched by a ghost, Gordon strongly encourages reckoning with it 'graciously,' attempting to offer it a 'hospitable memory.'[72]

-

Reckoning with the ghost entails a collective endeavour of exorcising its presence, where we must labour to identify and transform the socio-historical forces that produced it in the first place, so that we can create a different future.[73] An act of exorcism is not the same as silencing and domesticating the ghost by reducing its presence to intelligible or manageable language, such as hallucination and symptoms of a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Unless we recognise what the ghost is signalling to us by taking it seriously and trying to speak to it, Gordon warns, it remains as a spectre, wandering in the same violent conditions that made it appear in the first place.

Haunting in the Hiroshima memorial space

-

Facing up to the A-bomb drawings, I bumped into a rememory that belongs to somebody else. Instead of interpreting my affective experience as hallucination, vicariously repeating the original event of trauma, or introjectively identifying with the victims, what possibility would open up if my experience is seen as being haunted by the ghostly presence of 'picture humans'[74] in the drawings? What if we rename transmission of trauma 'haunting'? It is not too way off from an academic practice, if we consider psychoanalysis as a legitimate academic endeavour. Psychoanalysis, at least in the Freudian spirit, albeit with ambivalence, grapples with the 'uncanny,' 'mental infection' and 'coincidence,' among other haunting social phenomena, without necessarily resorting to the rational language of science. And so far as haunting is a widely observed social phenomenon, sociology must also grapple with it, as Gordon advocates.

-

With the theory of haunting, the ghostly presence of 'picture-humans' is to be recognised as victims' rememories. By transporting me momentarily to the scenes depicted, like rivers filled with corpses, picture-humans are signalling that violence that made their presence ghostly in the first place is not yet over with. But picture-humans ought not to be equated with the dead, since their presence emerges only in collaboration with the survivors, whose act of drawing 'inscribes life' to the dead by giving them embodied presence. Being haunted by the ghostly presence of picture-humans, therefore, is not the same as being possessed by the spirits of the dead.

-

Picture-humans are making demands for justice, but the colonial and state violence committed by both Japan and the Unites States is far from being over and redressed. The gaze of the picture-humans is directed not to accuse us for having survived the nuclear age; they urge us to take up the chance to put an end to the social conditions that keep us in the state of violence. They are asking us to listen to their demand by reckoning with them graciously, not quieting them down with the rational language of peace and psychoanalysis.

-

When you bump into somebody else's rememory, you may interpret it as being infected with other's trauma. Transmission of trauma is a name for affective recognition of the past violence that is still in operation in the present. In other words, trauma is a sign of a ghost, not the other way around. As a ghost, transmission of trauma signals to us that we have a chance to collectively turn traumatic memory into counter-memory, for the future.

Endnotes

[1] In late May 1974, a year before the thirtieth anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb, the Hiroshima station of NHK (Japan Broadcasting Company) announced its aim to collect drawings that 'illustrate the immediate aftermath of the bombing in Hiroshima and surrounding areas.' In about two months, close to 1,000 drawings were mailed or brought directly to the station. Many drawings were accompanied by letters that explained the drawings and expressed the feelings of hibakusha [atom-bomb survivors] as they drew their pictures. NHK placed another call for drawings in April 1975. For more detail on the drawings, see Naono Akiko, 'Embracing the dead in the bomb's shadow: journey through the Hiroshima memoryscape,' doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2002, chapter 5; Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Genbaku no E, (Atom Bomb Drawings by Survivors) Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2003.

[2] For the analysis of interview accounts, see Naono Akiko, Genbaku no E to Deau (Encountering with the Atom Bomb Drawings by Survivors], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2004.

[3] Sigmund Freud, 'Beyond the pleasure principle,' in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 18, ed. J Strachey, London: Hogarth Press, 1920, pp.1–64.

[4] Hudnall B. Stamm (ed.), Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers, and Educators, Towson, Maryland: Sidran Press, 1996. Antonius C.G. Robben discusses how transferential relationship is developed in encounters conducted by anthropologists during ethnographic fieldwork. See Antonius C.G. Robben, 'Ethnographic seduction, transference, and resistance in dialogues about terror and violence in Argentina,' in Ethos, vol. 24, no. 1 (1996):71–106.

[5] Helen Epstein, Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors, New York: Putnam, 1979; Nadine Fresco, 'Remembering the unknown,' in International Review of Psycho-Analysis, vol. 11 (1984):417–428; Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory , Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997; Marianne Hirsch, 'Marked by memory: feminist reflections on trauma and transmission,' in Extremities: Trauma, Testimony, and Community, ed. Nancy K. Miller and Jason Tougaw, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002, pp. 71–91; Dina Wardi, 'Therapists' responses during psychotherapy of Holocaust survivors and their second generation,' in Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 40, no. 4 (1999):479–85.

[6] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Natonalism, revised edition, London and New York: Verso, 1991, p. 9.

[7] The square was named after former apartheid Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom.

[8] Derek Hook, 'Monumental space and the uncanny,' in Geoforum, vol. 366 (2005):688–704, p. 693.

[9] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 688.

[10] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 701.

[11] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 696.

[12] Sigmund Freud, 'The uncanny,' in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17, ed. J Strachey, London: Hogarth Press, 1919, pp. 217–52, p. 226.

[13] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 698.

[14] Freud, 'The uncanny,' p. 236.

[15] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 701.

[16] As many as 140,000 ± 10,000 were killed by the end of December 1945 in Hiroshima alone and more have been killed slowly by the after-effects of radiation. Many of the dead remain unknown and unclaimed by anyone. See the Expert Committee for the Compilation of Materials to Appeal to the United Nations (ed.), To the United Nations, Hiroshima-shi and Nagasaki-shi, 1976, p. 31.

[17] Freud, 'The uncanny,' p. 241.

[18] Hook, 'Monumental space,' p. 698.

[19] This statement is inscribed on the Cenotaph for the Victims of the Atomic Bombing, located at the centre of the Peace Park. For controversy over this statement, see Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space and the Dialectics of Memory, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999, pp. 16–18.

[20] A nation-wide anti-nuclear sentiment swept Japan after a crew member of a Japanese fish boat (the Lucky Dragon) died as a result of having being exposed to the U.S. hydrogen bomb test in 1954. Positioning this Lucky Dragon Incident as the third Japanese tragedy, hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were remembered as the first and the second Japanese victims of nuclear weapons.

[21] This narrative is presented in one of the main panels displayed at the Peace Memorial Museum's permanent exhibit and has functioned as Hiroshima's official narrative. For analysis of the Museum as a discursive site for the struggle over the collective memory of Hiroshima, see Naono Akiko, 'Hiroshima as a contested memorial site: analysis of the making of the peace museum,' in Hiroshima Journal of International Studies, vol. 11 (2005):229–44.

[22] Those killed by the atomic bombings in Hiroshima include: American POWs, students from South East Asia, and most notably Korean residents who migrated after colonisation, and Korean forced labour brought from the peninsula toward the end of the war. The Memorial for the Korean Victims of the Atomic Bombing, which was erected outside the Peace Park and had remained there until the relocation in 1999, has long been the symbol of Korean victims' invisibility in the discursive space of Hiroshima.

[23] Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces, p. 15.

[24] For analysis of discursive operations of power in the Hiroshima's memoryscape, see Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces; Naono, 'Embracing the dead.'

[25] Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, p. 142.

[26] Dominick LaCapra, History in Transit, p. 74.

[27] Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, p. 143.

[28] Dominick LaCapra, History in Transit, p. 81.

[29] Dominick LaCapra, History in Transit, p. 81. In this context, LaCapra criticises Claude Lanzmann and his seminal film, Shoah.

[30] Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001, p. 41.

[31] Robert J. Lifton was also pivotal in officially institutionalising posttraumatic stress disorder, successfully listing it in the DSM-III in 1980, through his devoted assistance to the Vietnam Veterans.

[32] Robert J. Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991, p. 480.

[33] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 30.

[34] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 21.

[35] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 480.

[36] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 496.

[37] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 496.

[38] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 497.

[39] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 498. Here, Lifton equates the atom-bomb victims with the 'Japanese' which, as I argued in the previous section, would result in strengthening the ideology of the nation-state dominant in the Hiroshima's memoryscape and thereby erase the colonial memory of the Korean victims. This kind of de-historicisation is not unique to Lifton, however, but seems endemic in psychoanalytically-based study on trauma. See, for example, Cathy Caruth's analysis of Hiroshima mon Amour in Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

[40] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 499.

[41] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 518.

[42] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 518.

[43] Freud, 'Group psychology and the analysis of the ego,' in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud , vol. 18, ed. J Strachey, London: Hogarth Press, 1921, pp. 69–143, p. 105.

[44] Freud, 'Group psychology,' p. 105.

[45] Freud, 'Group psychology,' p. 105.

[46] Freud, 'Group psychology,' p. 107.

[47] Freud, 'Group psychology,' p. 107.

[48] Freud, 'Group psychology,' p. 107.

[49] Diana Fuss, Identification papers, New York: Routledge, 1995, p. 41.

[50] Strydom's identificatory acting out, however, could be analysed as a case of identification through 'mental infection.'

[51] Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma and Contemporary Art, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005; Bennett 'The Aesthetics of sense-memory,' in Memory Cultures: Memory, Subjectivity and Recognition, ed. Susannah Radstone and Katharine Hodgkin, New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2006, pp. 27–39.

[52] Bennett, Empathic Vision, p. 35.

[53] Bennett, Empathic Vision, p. 35.

[54] Bennett, Empathic Vision, p. 8.

[55] Hirsch, Family Frames, p. 22.

[56] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 72.

[57] Toni Morrison, Beloved, New York: Knopf, 1987, p. 36.

[58] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 74.

[59] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 74.

[60] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 74.

[61] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 76.

[62] For this kind of psychologised reading of Beloved, see Daniel Erickson, Ghosts, Metaphor, and History in Toni Morrison's Beloved and Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 26.

[63] Erickson, Ghosts, Metaphor, and History, p. 16.

[64] Hirsch, 'Marked by memory,' p. 76.

[65] Morrison, Beloved, pp. 35–36.

[66] Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 66.

[67] Gordon, Ghostly Matters, p. 7.

[68] Gordon, Ghostly Matters, p. 195.

[69] In her discussion of 'ghost films,' Bliss Cua Lim similarly suggests that ghost stories are 'historical allegories' to 'articulate historical injustice.' Bliss Cua Lim, 'Spectral times: the ghost film as historical allegory,' in Positions, vol. 9, no. 2 (2001):287–329, p. 288. Lim, however, does not make any reference to Gordon's work. I thank Janet Walker for directing my attention to Lim's writings.

[70] Gordon, Ghostly Matters, p. 65.

[71] Gordon, Ghostly Matters, p. 182.

[72] Gordon, Ghostly Matters, p. 64.

[73] See Gordon, Ghostly Matters, pp. 182–83.

[74] Saiki Toshiko, one of the survivor-artists and well-known hibakusha of Hiroshima, insists that what she and other survivor-artists produced are 'picture humans' and refuses to call the 'A-bomb drawings' drawings. For her, an act of drawing was that of giving life (back) to those victims who were reduced to 'objects' such as 'mounds of corpses' and 'piles of bones'; therefore, calling the 'A-bomb drawings' drawings, for her, would subject the dead to a kind of second murder.

|