Reconstructing the Perpetrator's Soul

by Reconstructing the Victim's Body:

The Portrayal of the 'Hiroshima Maidens'

by the Mainstream Media in the United States

Robert Jacobs

Introduction

-

For those working on the history of the bombing of Hiroshima, there is a stark contrast in the narration of the event when this is done from either the US or Japanese perspectives. Nowhere is this more evident than in the museums that specifically focus on the development and use of atomic weapons. Interestingly, the difference is immediately evident in the timeline of the museum narrations. At the National Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the exhibits narrate the story from about 1942 up until September 1945. The US narrative of the bombings is of technological prowess—it is about brilliant scientists making groundbreaking discoveries, about engineers and industry rapidly manufacturing incredibly complex technologies, and about thoughtful political leaders making difficult, bold, and wise decisions. It is a story about the US citizens who envisioned, designed and built the bomb (even though many were Europeans who became naturalised), and then benevolently used it, bringing World War Two to an end and saving countless lives, both for the US and Japan. The final displays in these museums note the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as being where the bomb was used. The cities are seen from above—from airplanes—and they appear to be empty landscapes without the presence of human beings.

-

By contrast, the Japanese narration of the bombings begins in August of 1945 and moves forward from there. The story is not about the development of the bomb, but about its use. The Japanese story is about the people who were killed and injured by the weapon; the scientific breakthroughs of its invention seem irrelevant. The perspective of the Japanese exhibitions, for example at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, is from the ground level, and is filled with human beings, injured or burned to death, and with the scorched things they left behind: reading glasses, lunch boxes, shadows.[1] While both narratives are focused on a singular event, the dropping of the two bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one is concerned only with what happened before the event, and the other is concerned with what happened that day, and its impact and legacy.

-

The narration of the bombings by the dominant press in the US is also a triumphant narrative about US can-do, scientific and technological prowess, industrial capacity, and the political bravery of its leaders. It is taken as fact that the only alternative to using the bomb was an invasion of the Japanese home islands, and that the bold decision to use the bomb made this unnecessary, sparing a much larger number of lives than it took. In this narrative, there are no individual Japanese people; they are present only as statistics, 200,000 killed, millions spared. The characters in this story are all US citizens.

-

This same structure is found in US mainstream media depictions of the journey of twenty-five young Japanese women who in 1955 were taken from their homes in Hiroshima to New York City to receive medical treatment. The women had disfiguring scars, inflicted on them by the explosion of the atomic bomb dropped in August 1945. They suffered from burns and keloid scars (collagen skin scarring that resulted from the burns) that had altered their faces and in some cases, crippled hands, arms and necks. The women had all been students when they suffered atomic attack. Many were on the way to school, while others were among those whose task was to help tear down houses to create firebreaks in the city centre in preparation for the kinds of firebombing that had already hit almost every Japanese city with a population of more than 50,000 people. The resulting scarring of their faces had so disfigured them as to make marriage impossible, and had caused many of them to live their lives in hiding for fear of name-calling or being stared at. As soon as they arrived in the United States, the women, who became known as the 'Hiroshima Maidens' (Hiroshima otome), fascinated the US mainstream press, who used their journey to obfuscate the nation's sense of guilt about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, by turning the whole event into a triumphant narrative of science and compassion. In this narrative the Japanese are allowed to be present but only in a childlike, dependent and ultimately grateful position. The heroes are the US doctors and philanthropists, who make the decisions, bear the costs and perform the miraculous surgeries, thus restoring life, happiness, and beauty to the Japanese women. In the mainstream press, the story of the 'Hiroshima Maidens' is a retelling of the traditional narrative of 'American Triumphalism,' referred to by David Serlin as a 'medicalized version of the Marshall Plan.'[2] As a result, when this triumphal story is told, echoing the narration of the use of the atomic bomb as closely as it does, the story works to further justify the use of atomic weapons, even as it serves to humanise the victims of the bombings. US can-do knows no bounds, first saving the Japanese from invasion, and then reconstructing the bodies of the innocent victims, children who got caught in the atomic crossfire.

-

In this essay I will examine several primary news stories printed by mainstream newspapers, magazines and newsreels in the United States at the time, and discuss the narratives, depictions, and discourses concerning the so-called Hiroshima Maidens. I will refer to the participation of two of the women on a television show in which they were to experience a surprise encounter with one of the servicemen who took part in the bombing of Hiroshima. I will also survey the existing critical literature regarding the depiction of these Japanese women in the US media at the time of their visit. Ellen Schrecker, for example, notes that the uncritical 'triumphalist' US view elides other aspects of the Cold War to create an oversimplified and distorted version of its history that serves to justify Washington's past and present quest for hegemony.'[3] This is no less true of US triumphalist depictions of that first act of the Cold War, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and of its victims, the hibakusha.[4]

The journey of the 'Hiroshima Maidens' to the United States

-

The idea of taking the Japanese women to the United States for medical treatment originated in the peace work done by the Reverend Kyoshi Tanimoto in Hiroshima during the years after the bombing and after the end of US occupation. Tanimoto had been seeking medical treatment from the Japanese government for the 'keloid girls' who were members of his church in Hiroshima. Many had gone to Tokyo for plastic surgery, which had been only marginally successful. When Reverend Marvin Green (Tanimoto's schoolmate from his seminary days at Emory University, Atlanta) visited Hiroshima, he suggested to Tanimoto to take the girls to the US for treatment, since techniques there were both better funded and surgically more advanced than those available in post-war Japan. Tanimoto had been to the US two previous times on speaking tours to Methodist churches, aimed at raising money for his Hiroshima Peace Center project. Tanimoto had first been introduced to the US public in John Hersey's 1946 book, Hiroshima.[5] When US peace activist and Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins visited Hiroshima a year later as part of his program for US sponsorships of Hiroshima war orphans, Tanimoto mentioned Green's idea to him. As a result, Cousins became very enthusiastic and began to organise support and logistics for the trip. While Tanimoto had envisioned the project as limited to the members of his congregation and as having a specifically charitable, Christian focus, Cousins gave the project a more political outlook. The doctors he enlisted included girls who were not members of Tanimoto's congregation, and he involved Quakers as primary participants in the effort. However, whereas Cousins excluded Tanimoto from all roles, except fundraising, their conflict and falling out were kept largely out of the view of the media.[6]

-

Nevertheless, almost all of the chosen Japanese women were Christian and many had been members of the Tanimoto's Methodist Church. Tanimoto and Cousins arranged for the women to travel to the US and receive free reconstructive surgery aimed at restoring their beauty and the functionality of burned body parts, while giving them some hope of a normal life. Cousins spearheaded the fundraising of the money for their yearlong stay, soliciting donations from corporations to pay for transportation, arranging accommodation for the women with Quaker families in the New York City area, as well as the gratis services of Mount Sinai Hospital and its staff of world-famous plastic surgeons. Cousins even adopted one of the Japanese women into his family.[7]

-

Each of the women received multiple surgeries, including skin grafts, face lifts and reconstructive surgeries to separate fingers that had been fused together by the intense heat of the atomic blast, and restoring the use and functions of their hands. One woman who had not been able to raise her head from a bowed position since the bombing regained the free use of her neck. They stayed in the US for over a year, eventually returning to Japan in two groups, once their course of plastic and reconstructive surgeries was complete.

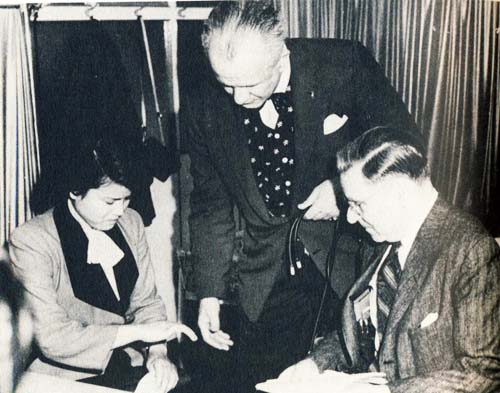

Figure 1. 'Hiroshima A-Bomb Survivors Face Brighter Future,' proclaimed the text accompanying this photograph of Mitsuko Kuranoto and Emiko Takemoto as they arrive at Mitchel Air Force Base on Long Island, NY. Source: AP Wire 9 May 1955.

Figure 1. 'Hiroshima A-Bomb Survivors Face Brighter Future,' proclaimed the text accompanying this photograph of Mitsuko Kuranoto and Emiko Takemoto as they arrive at Mitchel Air Force Base on Long Island, NY. Source: AP Wire 9 May 1955.

|

-

Meanwhile, the US government was concerned that the presence of the Japanese women in the country would provoke anti-nuclear sentiments and boost opposition against the Eisenhower administration's nuclear testing program and heavy reliance on nuclear weaponry, intended to counter the Soviet Union in the international game of chicken that the Cold War had become. In fact, the State Department sent a cable to Japan cancelling permission for the trip, but it arrived just as the women were to depart, and was ignored by local airbase commander General John C. Hull.[8] Later, public fascination with the group of Japanese women led to an effort on the part of other US cities to sponsor their own hibakusha to travel to receive medical treatment, but this move was derailed by the US government.[9]

-

Cousins and the other peace workers involved had dual motives: first, and certainly foremost, to help restore the wellbeing of the hibakusha, but also to generate media coverage in the US that was sympathetic towards the victims of the atomic bomb. Cousins was not as interested in critiquing the US nuclear program as he was in fostering reconciliation between the former combatants. He wanted the Japanese to witness US compassion and the US public to encounter the victims of the atomic bombings not as enemies but as innocents.

The portrayal of the 'Hiroshima Maidens' by the mainstream media of the United States

-

The visiting Japanese women were generally depicted as childlike, innocent and grateful. They were uniformly spoken of as being 'almost pathologically shy,' and then 'blossoming in the warmth they shared in the homes of American "parents".'[10] Endearing stories were told of how one woman used the trash bin in Mount Sinai Hospital to post letters for several months, mistaking it for a letter box, before realising her error, and how another assumed her host parents' names were 'honey' and 'darling,' only realising her mistake after seeing a TV husband and wife using the same pet names.

-

A Time magazine article claimed that Shigeko Niimoto was the 'youngest and prettiest of Oyster-Fisherman Masayuki Niimoto's three daughters.'[11] Shigeko had been thirteen when the bomb was dropped; she was on her way to high school when the bomb severely burned her face, chin and arm. Standing on a bridge less than a mile from Ground Zero, she had been one of the closest people to the blast to survive in the open. Much was made of the need to restore the beauty of the Japanese women, and newspaper coverage focused on the likelihood of their marriage prospects, to a degree we would now consider unhealthy. 'Of the 6,000 Hiroshimans who suffer lingering injury from fire or radiation,' claimed one article, 'the most poignant cases have been these girls who reach marrying age bearing the akuna no tsume ato—the Devil's claw marks—as the Japanese describe the Bomb scars.'[12] There is no record of keloid scars being called that in Japan, and in fact the expression 'akuna no tsume ato' is an old expression meaning 'nail marks of the Devil' that had long been used to describe the physical scarring left on the land by natural disasters such as typhoons, tsunamis and earthquakes. The use of this phrase evoked the sense that the scarring of the women could be seen as the after-effect of natural forces rather than the wounds inflicted by a deliberate act of warfare.

-

The darkest moment for the project came on 24 May 1956, when Tomoko Nakabayashi died on the operating table during a minor surgical procedure. But even this tragedy was reconstructed as a cosmetic rather than a human story, with one headline proclaiming: 'Beauty Hunt Fatal—Hiroshima Maiden Dies In Surgery.'[13] The implication of such editorialising is that the fault lay with the desire of the woman to be beautiful, rather than with any medical error on the part of her doctors.

-

It was imagined that without the surgical intervention in the US, the women would have been fated to live isolated and incomplete lives. Shigeko Niimoto, for example, was declared to have 'no hope of marriage.'[14] Another article described how Suzue Oshima had been living an isolated and dejected life in Hiroshima. She did not go outside 'for years' and then would not socialise or go swimming: 'she tried not to think about anything but her work as the unscarred girls around her got married one after another.' Her discovery of Tanimoto's group of keloid girls provided her 'only social contact.' Suzue and the other girls 'had reached marriageable age and yet were ashamed to show themselves in public.'[15] The use of the term 'maiden' reveals the focus on the lack of romantic prospects for the women while reinforcing the image of their innocence and childlike nature.

-

Newspaper stories dwelt on such things as the fashion choices of the women, particularly their interest in Western style dress and hairdos: 'They have adopted sleek Italian hairdos, colored ballerina slippers and other US fashions'; this has helped them to 'no longer shrink from meeting people as they did at home.'[16] Colonialist discourse such as this positioned Western fashion as liberating or simply superior to Asian styles.

Figure 2. 'The Maidens tour Manhattan,' proclaimed this picture taken in Central Park in Collier's, 26 October 1956, p. 92.

Figure 2. 'The Maidens tour Manhattan,' proclaimed this picture taken in Central Park in Collier's, 26 October 1956, p. 92.

|

-

Triumphalist stories emphasised the delicate sensitivity of the US public in relation to the way the women's disfigurement was represented. Special provisions were made so that they were allowed to carry passports without identification photos, so as not to shame them. In a bizarre twist, two of the women appeared on the television show This Is Your Life during an episode in tribute to Tanimoto, and were shown behind a screen in silhouette so as to spare them the humiliation of presenting their disfigured faces on national TV. They were not, however, spared the spectacle of an inebriated Captain Robert Lewis, co-pilot of the Enola Gay (the plane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, and on them), who drunkenly expressed remorse for his actions. The appearance of Lewis on the show would outrage veterans, but the on-air appeal for donations to aid the women's cause would subsequently raise $55,000.[17]

-

A great deal was made in the media of the capacity of US love to heal the victims of the bomb: the love shown to the Japanese women by the peace activists, by the Quaker families that hosted them, and especially by the doctors and medical staff that treated them. In this sense, the US nation was depicted as the benevolent restorer of life for the hibakusha rather than as the agent of their childhood crippling. One of the women was widely quoted in the newspapers as saying, just before being wheeled into the operating room for another session of surgery, 'Tell Dr. Barsky not to be worried because he cannot give me a new face. I know that this is impossible, but it doesn't matter; something has already healed inside.'[18]

-

A 1955 Collier's magazine article titled 'Love Helped to Heal the "Devil's Claw Marks"' claimed that one of the women declared after returning to Japan: 'I am so happy, so very happy. If it had not been for the atomic bomb I would never have gone to America.' Underneath a Brooklyn Dodgers pennant in her room back in Hiroshima, she was said to have wondered with amazement: 'Why did former enemies treat us like daughters?' The article made it clear that it was 'the love of the Americans' who brought her to the United States and who restored her beauty that accomplished this emotional and spiritual miracle.[19]

-

The US public learned that such compassion had resulted in one of the few non-Christians among the hibakusha to reconsider her faith: 'She went through an inner struggle,' reported the Rome News-Tribune (GA) and then 'abandoned Shinto for a Christian church.'[20] Another of the women was quoted as saying: 'When I think about how kind everyone is, I'm glad I've never been bitter about the bomb.'[21]

-

The idea that the Japanese women 'forgave' the United States for the use of the atomic bomb was a commonly repeated theme. Moviegoers learned this lesson from the Universal International Newsreel, dated 8 November 1956, shown in movie theatres across the country. A news report about the hibakusha returning to Japan shows the women happily waving to friends and supporters from an airport tarmac as narrator Ed Herlihy informs: 'they say now that their sacrifice was worth it if only the atom is never used again in war.'[22]

-

Prior to their trip to the US, the girls were said to have totally withdrawn from public life in Japan—some even attempting suicide. But this was now behind them, claimed one article: 'From a twilight society in Hiroshima they were now basking in love and attention.'[23] This was accomplished through love and expert professionalism, since '[t]o the attending doctors…signs of mental health are as important as the surgical gains.'[24]

-

A primary focus of most of the media coverage was the skill and technical ability of the US doctors. This discourse reinforced narratives of US technological prowess that traditionally accompanied mainstream media discussions of the earlier development and use of atomic weapons. Each of the women had received up to twenty operations before traveling to the US. 'Japanese plastic surgeons did their best,' claimed Time magazine, 'but the scar tissue kept coming back.'[25] This explains why when the women traveled to the US: 'it was decided to take along three Hiroshima surgeons, to study the American plastic-surgery techniques.'[26] This medical training was done free of charge.

-

Colonialist discourse can be seen in references to the 'backward' nature of Japanese medical technology. Many articles in the mainstream press referred to the lack of skill and even of the lack of professionalism of Japanese doctors, who had been 'given information on treating the survivors by the American funded Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission,' but since there were so many to treat they 'never got around' to treating the 'Maidens.'[27] Upon their return to Japan, a 'spokesman for the Hiroshima Municipal Doctors' Association reportedly was "surprised to see such conspicuous improvement".'[28]

-

The US doctors, by contrast, were portrayed as wonder workers. A headline in the New York daily World Telegram & Sun proclaimed: 'Surgeon's knife battling A-Bomb'; while another article noted that even though 'the required surgery in most cases was extraordinarily complicated,' the US doctors worked tirelessly and precisely. The results were described as 'dramatic':

In Manhattan's Mount Sinai Hospital last week plastic surgeons removed the dressing from the face of a 23-year old Japanese girl…and noted with satisfaction that her extensive skin graft had been an almost perfect take. The contours of the girl's face were almost normal again.[29]

-

A Japanese boy was reported to have proclaimed to his mother when his sister, a member of the group who traveled to the US, returned to Japan, 'Look Okasan; she's cured!' US readers learned that one of the hibakusha confessed upon her return, 'I have never before known real happiness.'[30] Invoking rhetoric befitting wartime, Time magazine presented a 'before and after' picture of one of the women with the text under the graphic declaring: 'From horror to triumph.'[31]

Figure 3. Shigeko Niimoto's photographs are labelled 'horror' and 'triumph' in Time magazine, 10 December 1956, p. 76.

Figure 3. Shigeko Niimoto's photographs are labelled 'horror' and 'triumph' in Time magazine, 10 December 1956, p. 76.

|

-

In a way, Cousins's goals had been achieved, as the US media presented the Japanese women as innocent and sympathetic victims of the bomb. But it was not so simple. This media narrative did much more than simply present the so-called Maidens as victims and human beings—it presented the US characters in the story as the truly heroic actors. In countless articles, the real story was about US benevolence and technological ability. US doctors could accomplish what Japanese doctors could not, successfully performing the surgeries involved, and restoring the beauty, and therefore the wellbeing of the afflicted women. And in this we can recognise a familiar US narrative about atomic weapons. Indeed, from 1945 on, US discourses regarding the use of atomic bombs in Japan emphasised the fact that the bombs 'saved lives.' This is based on the now discounted belief that the Japanese surrender was a direct reaction to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Japan.[32] The triumphalist US argument for the use of the atomic bomb has it that if the bombs had not compelled the Japanese to surrender, the only alternative would have been an invasion, in which a larger number of Japanese lives would have been lost than were killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the lives of many of the participating Allied servicemen. Thus, the dominant discourse concludes that it was US technological prowess exemplified by the building of the bomb, and US political courage demonstrated by the decision to use the bomb, which 'saved lives' in the end. This paradoxical discourse would come to typify Cold War logic, in which whole societies might have to be destroyed in order to save society.

Figure 4. 'Active and Passive Participants.' Source: Chugoku Shinbun, reprinted in, Rodney Barker, Hiroshima Maidens, pp. 118–19.

Figure 4. 'Active and Passive Participants.' Source: Chugoku Shinbun, reprinted in, Rodney Barker, Hiroshima Maidens, pp. 118–19.

|

The return of the 'Hiroshima Maidens' to Japan

-

Among the threads that reinforce the US triumphal narrative are several keys. The Japanese women were all students when they suffered the atomic attack, thus sparing them of any complicity in the Japanese war effort, and casting them as victims themselves of Japanese military aggression. While there were certainly many older people in Hiroshima who were also scarred badly with keloids, their age implicated them in Japanese atrocities and aggression. They were also past the age at which their beauty could be generously restored. The recipients were also all female. Clearly the children who were victims of the bomb were equally male and female, and presumably there were as many scarred boys as there were girls, who also could not marry, and who were forced to live in the 'twilight society of Hiroshima.' But the presence of Japanese males in their twenties would have evoked memories of Japanese soldiers, and therefore they were not considered suitable recipients of US largess. Almost nowhere in the press coverage was any mention of the fact implicit in the very existence of the hibakusha, that the bomb had been dropped on civilians, rather than on combatants or on a military target.[33] These were mostly children who were attacked on their way to school. But even as this fact is mentioned, it is not placed in any kind of historical context.[34]

-

Many of the media stories express hostility and suspicion about Japan and Japanese society. While the families of the women are described as grateful and thrilled to have their daughters 'reconstructed,' other Japanese are depicted as jealous and mistrustful of US efforts. One article claimed that in the Japanese press, their case was 'sometimes exploited in a horror campaign against US use of atomic weapons,' but self-assuredly concluded that 'the story quickly turned into one of medical triumph.'[35] Another article projected the new political lines of the day onto the Japanese, where it was reported that '[t]here were communist-inspired rumors that the girls would be exhibited as side-show freaks or be used as laboratory guinea pigs.' There was speculation that the Japanese believed the US government was 'secretly financing the project as counterpropaganda to the H-bomb test fall-out that injured Japanese fishermen in 1954,' referring to the mass exposure of Pacific Islanders and the crew of a Japanese fishing boat to high levels of fallout radiation after the US test of the Bravo weapon on 1 March 1954.[36] In media stories, these Japanese were presented not as innocent and trusting ones like the 'Maidens,' but as treacherous, probably males, like those who had been responsible for World War Two. They contrasted rather conveniently with the kindly and benevolent US citizens who allegedly had only the wellbeing of the women in their hearts. Just like in World War Two, it was easy to see from these accounts who the good and bad guys were. In fact, one article points out that the 'Maidens' were starving in Japan until 'the U.S. government sent in shiploads of wheat to make noodles,' which kept them alive.[37]

-

Nevertheless, when the women returned to Japan after 1956, they faded completely out of the attention of the mainstream press in the US. They faced a difficult readjustment in Japan, including the resentment of those who did not receive special medical treatment, as well as a return to a generally impoverished city with little economic prospects. There were almost no follow-up stories trumpeting the happy marriages and normal lives for which the women presumably were now destined. The story was over once the US exited the stage. After a year of non-stop self-congratulation for their generosity and expertise, the US media could now claim that 'without unduly patting themselves on the back most Americans looked at the Hiroshima Maidens project as a simple gesture of good will toward a particularly unfortunate group of war sufferers.'[38] Nice, clean, finished. But who, in the end, was really the more reconstructed of the participants?

Conclusion

-

The journey in 1955 of the so-called Hiroshima Maidens from Japan to the United States to receive cosmetic and reconstructive surgeries had provided an opportunity for the mainstream US media to re-envision the nation as the healer of the hibakusha rather than as the perpetrator of their wounds and disfigurements. Depictions of the care and treatment of the Japanese women emphasised the capacity for generosity, expertise and Christian love of US citizens. This narrative restated the triumphalist discourse of US technological prowess and benevolence that had characterised the initial use of atomic weapons on Japanese civilians. An examination of contemporary stories in mainstream newspapers, magazines and newsreels provides a triumphalist celebration of the United States and a thorough reconstruction of the US role in the lives of the hibakusha as paternal caregivers rather than perpetrators.

-

While the efforts of those responsible for the surgeries did affect the lives of the Japanese women who travelled to the United States, the significance of their efforts to affect the attitudes of the US public towards the victims of the atomic bombings is far less clear. Paul Boyer claims that the 'project helped to restore Hiroshima to the forefront of memory while furthering the test-ban cause,' but the evidence is circumstantial.[39] It is clear that the presence of the women in the United States, and the publicity that accompanied them, raised awareness of the plight of the hibakusha, but the long-term ideological effects of their journey await further scholarship. Additionally, the opinions of Cousins and the other peace-workers who organised the trip in part to emphasise, in Robert Jay Lifton's words, more 'reconciliation, than atonement,' await further analysis.[40]

Endnotes

[1] Human shadows were scorched onto steps and walls from the flash of the bomb. The victims' bodies were carbonised but their shadows remained behind.

[2] David Serlin, Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004, p. 117, quoted in, The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 2 (April 2006), p. 531.

[3] Ellen Schrecker, 'Introduction: Cold War triumphalism and the real Cold War,' in Cold War Triumphalism, ed. Ellen Schrecker, New York and London: The New Press, 2004, 1–24, p. 7.

[4] Hibakusha is the Japanese word used for those who survived the bomb. It literally means 'explosion-affected person.'

[5] John Hersey, Hiroshima, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946.

[6] John Hersey, 'A reporter at large; Hiroshima: the aftermath,' in The New Yorker (July 15, 1985), pp. 58–59.

[7] Lawrence S. Wittner, 'Gender roles and nuclear disarmament activism, 1954–1965,' in Gender and History, vol. 12, no. 1 (April 2000): 197–222, p. 209.

[8] James H. Foard, 'Vehicles of memory: The Enola Gay and the streetcars of Hiroshima,' in Religion, Violence, Memory, and Place, ed. Oren Baruch Stier and J. Shawn Landres, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006, pp. 117–31, p. 127.

[9] These efforts would be led by a group of citizens and ministers in Mobile, Alabama. See, Rodney Barker, The Hiroshima Maidens: A Story of Courage, Compassion, and Survival, New York: Viking Press, 1985, pp. 82, 118–119.

[10] Gloria Kalischer and Peter Kalischer, 'Love helped to heal the 'Devil's Claw Marks,' in Collier's, vol. 138, no. 9 (October 26, 1956), p. 92. The idea of the physical scarring of the hibakusha as being 'natural' would be echoed over a decade later by Ibuse Masuji who wrote of the effects of the bomb as not unlike that of natural disasters. See Ibuse Masuji, Black Rain, Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1969.

[11] 'Young Ladies of Japan,' Time (24 October 1955): 53–54, p. 53.

[12] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 49.

[13] Barker, Hiroshima Maidens, p. 137.

[14] 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 53.

[15] Joy Miller, 'A blinding flash, white heat, then death: the first atomic bomb,' in St. Petersburg Times (31 July 1955), p. 11.

[16] 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 54.

[17] This incident plays a major role in Rodney Barker's book on the women, and in a 2004 puppet theatre play by playwright Dan Hurlin. See Barker, The Hiroshima Maidens; David Rakoff, 'Theater; Hiroshima bomber and victims: this is your (puppet's) life,' in The New York Times (January 11, 2004), sec. 2, p. 3. The show was filmed two days after the women arrived in the US; see Foard, 'Vehicles of memory,' p. 127.

[18] 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 54.

[19] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 94.

[20] Ara Plastro and Harry Altshuler, 'For the first time: Hiroshima Maidens tell of bombing; its aftermath,' in Rome News Tribune (23 January 1956), p. 2.

[21] Though she followed this statement with the request, 'Just please — no more Hiroshima,' see Miller, 'A blinding flash,' p. 11.

[22] News in brief, Universal International Newsreel (November 8, 1956). Note the use of the word atom rather than the more accurate atomic bomb.

[23] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 94.

[24] 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 54.

[25] 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 53.

[26] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 92.

[27] Miller, 'A blinding flash,' p. 11.

[28] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 95.

[29] Barker, Hiroshima Maidens, p. 102; 'Young ladies of Japan,' p. 53.

[30] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 49.

[31] 'Before & After,' Time, vol. 68, no. 24 (December 10, 1956, p. 76.

[32] Historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa has shown through an examination of the records of the wartime Imperial Japanese military that it was the declaration of war on Japan by Russia on 9 August 1945, that is most directly responsible for the Japanese surrender. See Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

[33] This was, however, mentioned in the Universal International Newsreel, cited note 22.

[34] Michael J. Yaveneditti makes the point that the women 'struck sympathetic chords among Americans in ways that twenty-five males and females of varying ages would not.' See, Yavenditti, 'The Hiroshima Maidens and American benevolence in the 1950s,' in Mid-America: An Historical Review, vol. 64, no. 2 (April-July 1982): 31–39, p. 34.

[35] 'Before & After,' p. 76.

[36] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 92. 'Bravo' tested the first deliverable thermonuclear weapon and the subsequent radiation exposures put the word 'fallout' into common usage.

[37] Plastro and Altshuler, 'For the first time,' p. 2.

[38] Kalischer and Kalischer, 'Love helped,' p. 92.

[39] Paul Boyer, 'Exotic resonances: Hiroshima in American memory,' in Hiroshima in History and Memory, ed. Michael J. Hogan, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 143–67, p. 151.

[40] Robert Jay Lifton and Gregg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: A Half-Century of Denial, New York: Avon Books, 1995, p. 255.

|