Topographies of Trauma:

Dark Tourism, World Heritage and Hiroshima

Mick Broderick

Introduction

-

This visual essay seeks to explore the relationship between the Hiroshima Peace Park as a site of mass human suffering and the debates concerning representation, commemoration and place. It draws from the recent scholarship in the emerging field of Dark Tourism[1] and key insights from theorists in memory studies, media philosophy and trauma such as Lisa Yoneyama, Akira Lippert and, in particular, Maria Tumakrin's work on 'traumascapes' and Maya Todeschini on female hibakusha.

-

The essay relates to three separate site visits by the author to Hiroshima from 2007 to 2009, while a guest of the Hiroshima Peace Institute, the City University of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Peace Film Festival.[2]

Figure 1. The author. Source: Photo by Robert Jacobs.[3]

My textual meanderings and methodology mimic tourist encounters at such commemorative sites. Here and there I may pause to reflect self-critically, take a discursive snapshot (sometimes carefully composed, at other times seemingly rushed to capture an opportunistic moment), browse for souvenirs, 'people watch' other tourists, take in the smells and sounds—all the while evaluating my prior knowledge and expectations against the actual in situ experience. Hence, some of my activities—like those of many tourists visiting these sites—are planned, or have an agenda; some rely on guidebooks, advice from friends, local knowledge; others might be accidental encounters, or embrace unforseen synergies and synchronicities. In this way my occasional self-reflexive approach gestures towards other academic methodological genres in the humanities, such as ficto-criticism, performance writing and life narrative, in my central exploration of how national trauma might be negotiated within the iconic confines of Hiroshima's Peace Park.

-

During my wanderings through the Peace Park and nearby sites that officially commemorate the A-bombing, I encountered a puzzling array of intersecting interests.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

| |

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

|

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

| |

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

|

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

| |

Figure 7. Photo by Robert Jacobs

Figure 7. Photo by Robert Jacobs

|

For instance, I was bemused—and somewhat intimidated—to encounter dozens of black vans driven by right-wing, pro-military, yakuza-associated thugs who on a regular basis harass the mayor and Hiroshima City Council officials via loudspeakers, while encircling City Hall and occasionally the Park (Figure 7). In the lead-up to the 2009 national election just after the August commemorative dates, posters for the marginal, pro-nuclear weapons Happiness Realization Party could be found all over Hiroshima. On 'Hiroshima Day' I witnessed anti-war Buddhist monks chanting at the Dome (Figure 2), protesters assembled to march on the local nuclear power utility (Figures 4 & 5), a performance artist writhing about in agony (Figure 6), and scrums of local and international electronic media (Figure 3), to name but a few. But what, and why, do we remember, and what have we forgotten, about Hiroshima?

Remembering Hiroshima

-

In the planning stages for the atom bombing of Japan, the US military and chief scientists of the Manhattan Project identified key 'virgin' sites for the special bombs—cities that had been deliberately exempted from the ferocious ongoing campaign of firebombing that decimated scores of cities and towns across the Japanese archipelago.[4] According to historian Richard Rhodes (whose landmark 1986 book The Making of the Atomic Bomb won the Pulitzer Prize),[5] of the four primary targets, Hiroshima was ostensibly selected because of its military garrison, but the city's wide delta, costal location and surrounding hills enabled additional analysis of the bomb's physical destructive capacities. Dropped from 31,000 feet by parachute, the detonation was controlled to airburst approximately 600 metres above the T-shaped Aioi bridge (which spans the juncture of the Hon and Motoyasu Rivers) in order to maximise the concussive effects of blast and penetration of radiant heat. After its lengthy descent 'Little Boy' drifted slightly off-target a couple of hundred metres to the southeast where its instantaneous uranium fission explosion released the equivalent energy of over 12,500 tons of TNT directly above the Shima hospital.[6] It was the peak of summer and 8:16am local time on 6 August 1945.

-

Less than two hundred meters from the bomb's hypocentre (ignition point) on the banks of the Motoyasu River was the Hiroshima Industrial Promotion Hall, a Czech designed secession-style building completed in 1915 which, according to Lisa Yoneyama, is 'a quintessential sign of Japan's early-twentieth-century imperial modernity.'[7]

Figure 8. Industrial Promotion Hall, post card, circa 1930

The explosion occurred almost directly above the five-storey Industrial Promotion Hall, melting its copper clad dome, crushing its brickwork, shattering its windows, collapsing its central staircase and pulverising its roofs, interior walls and floors.[8] The following clip from the anime Barefoot Gen (Dir: Nakazawa Keiji) demonstrates the power of Japanese animation (and its manga origin) to visualise the 'unthinkable.'[9]

Video 1. The atomic detonation above Hiroshima in Barefoot Gen (1983).

At the point of ignition the temperature of the nuclear chain reaction was hotter than the surface of the sun. Within a second, a ball of radioactive plasma had expanded to 280 metres wide before engulfing and consuming the atmosphere and all material elements within its growing diameter.

Figure 9. A section of the diorama in the Peace Museum

-

Underneath, the prompt radiation and intense thermal heat of nearly 4,000 degrees centigrade razed the building's contents. The human occupants were simultaneously irradiated, crushed and incinerated. According to Rhodes, those exposed within 700 metres of the initial fireball 'were seared to bundles of smoking black char in a fraction of a second as their internal organs boiled away.' In the following days witnesses observed that 'roasted' humans in 'small black bundles now stuck to the streets and bridges and sidewalks' and 'numbered in the thousands.'[10]

Figure 10. A view of the former business district at the City Hall Museum

Across the river, the commercial hub of the city (now the location of the Peace Park) was similarly decimated. For kilometres around ground zero, only a few reinforced concrete buildings remained standing, though these too were shattered internally by blast and gutted by heat and flames. An ensuing firestorm peaked a few hours later and annihilated the remnants of the city. Of the 76,000 buildings in Hiroshima 70,000 were demolished or severely damaged with 48,000 destroyed totally.[11] The city of Hiroshima was effectively erased.

Figures 11 and 12. US Strategic Bombing Survey, 30 June 1946.

-

Within a one-and-a-half kilometre radius the heat caused roof tiles to bubble and crack. Telegraph poles four kilometres away were charred from the heat flash. Inanimate objects and human beings subjected to the blinding light and heat became photographic traces etched into various surface textures such a walls, floors, steps and bridges. As Akira Lippert has eloquently argued:

What was intimated in the radioactive culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries erupted at full force in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: if the atomic blasts and blackened skies can be thought of as cameras, then the victims of this dark atomic room can be seen as photographic effects. Seared organic and non-organic matter left dark stains, opaque artefacts of once vital bodies, on the pavements and other surfaces of this grotesque theatre. The "Shadows," as they were called, are actually photograms, images formed by the direct exposure of objects on photographic surfaces.[12]

Figures 13 and 14. Nuclear shadow effects (human and material) on local structures

| |

|

-

The intensity of the nuclear detonation created unimaginable heat and blast pressure instantaneously. On 6 August the city was populated by about 280,000 civilians with an additional 48,000 soldiers. Approximately 70,000 died instantly and a further 70,000 were fatally wounded. By the end of 1945 the number of fatalities had reached 140,000—more than one-half of the city's entire population.[13]

Genbaku Dome and Hiroshima Peace Park

-

The environs of the Peace Park at Hiroshima have been a major tourist destination for well over 50 years. According to Maria Tumarkin, at any such 'traumascape,' irrespective of privileged national narratives, the diverse communities of victims pose the question of 'how widely divergent cultural traditions of dealing with death and memorialisation should be reconciled when victims come from different countries and cultural backgrounds?'[14] As Yonemaya reminds us, and the Peace Park controversially commemorates, allied POWS and interned Korean and Chinese slave labourers in their thousands were also victims of the A-bombings.[15] Over the past 64 years specific monuments to these communities have been erected within the Park and narratives modified among the permanent display descriptions at the Peace Museum to acknowledge these divergent histories.

-

The evolution of the site and its official excising by the Hiroshima City government as a national memorial commenced under Allied Occupation (1945–1952) and has continued in various forms over the past decades; for example, the former International Exhibition Hall, now a bombed-out shell called the Genbaku Dome, has been preserved and given World Heritage status in 1996 by a contentious United Nations listing.[16] At the time of the UNESCO nomination and later discussion and vote, both China and the USA objected, for different reasons, to the prospect of the site's privileged status receiving permanent international recognition in this manner.[17] The US had previously objected to sites associated with war, such as the nomination of Auschwitz-Birkenau, although at one point US delegates suggested a joint US-Japan nomination of either the Fermi laboratory in Chicago (where the first controlled nuclear reaction took place) or the Trinity test site near Alamagordo in New Mexico, alongside Hiroshima and the Dome.[18] But this strategy only alienated the Japanese and strengthened their pursuit of the Dome's nomination as a modern, transformative landmark of world peace.

Figure 15. UNESCO site plan of the Peace Park

-

As Beazley suggests, the Dome, Peace Park, and perhaps generically 'Hiroshima' itself, stand as a 'paradox'. Its metonymic function is primary. And while it represents many things to many people, for the UN committee that adjudicated the veracity of its World Heritage nomination and listing, 'there is no comparable building anywhere in the world'. The committee concluded that the:

overriding significance of the Dome lies in what it represents: the building has no aesthetic or architectural significance per se. Its mute remains symbolize on the one hand the ultimate in human destruction but on the other they communicate a message of hope for a continuation in perpetuity of the worldwide peace that the atomic bomb blasts of August 1945 ushered in.[19]

This UNESCO rationale foregrounds the duality of the Dome and the paradox of Hiroshima's unique status, simultaneously connoting the devastating effects of an atomic weapon, while serving to warn future generations against war.

-

As one of the first ruins of the nuclear age, the cultural and historical complexity of the Genbaku Dome comes into stark relief in the period immediately prior to, and during, the commemorative 6 August anniversary each year. This anniversary calendar is similarly informed by the defeat of Japan and the unprecedented surrender by the Emperor on 15 August, after a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August (originally targeting Kokura which was bypassed due to poor weather and visibility on the day) and the belated Russian declaration of war the same day. The constellation and conflation of conflicting anniversary dates understandably adds to the ambiguity and ambivalence of the site.

-

Following an international competition in the late 1940s, the Peace Park design was awarded to Tange Kenzo, a world-renowned architect, who had previously worked on spaces during the war celebrating imperial Japan.[20] On a number of plaques located at the perimeter the Japanese government proudly extols the virtues of the Park's message of peace as being entirely self-evident, boldly claiming that from the architecture and landscaping: 'Visitors immediately sense the intention of the structure and the superior spatial design, through which Tange attempts to connect the act of seeing with the act of praying for the A-bomb victims.'

| |

|

Figures 16 and 17. Explanatory plaque and cenotaph.

|

The claim is quite dubious and it remains highly contentious to assert an 'immediate,' uniform response aligning vision with prayer, irrespective of audience and subjectivity. It is an instance of how a national narrative is constructed to direct scopic responses, containing reaction, rather than opening the space to the plurality of emotions that the cenotaph evokes.

Dark Tourism

-

In their pioneering work, Dark Tourism, John Lennon and Malcolm Foley identify an increased interest in death, disaster and atrocity as a growing phenomenon of late-twentieth and early twenty-first century tourism, suggesting such trauma sites draw visitors as modern pilgrims.[21] Dark Tourism is distinguished from earlier, traditional modes of encountering calamity and mass suffering, according to Lennon and Foley, since it is informed deeply by the 'late modern' world. While pilgrimage has been recognised as one of the earliest forms of tourism and often, but not always, associated with individual or group death, such traditional relationships tend to evoke religious or ideological connotations. These periodic visitations or spiritual journeys are usually marked by calendars with anniversary dates of significance repeatedly observed. 'Whatever the religious and social significance of these practices, the outcome is to leave a "permanent" site which those who wish can visit, knowing that the corpse or individual is close by.'[22] Such processes are regulated and ritualised and frequently conform to belief systems that require the dead be honoured and ensure the departed souls/spirits are respected.[23]

-

Ancient repositories of the dead, whether they be for kings, popes, prophets, emperors or pharaohs, were frequently assigned elaborate and monumental buildings, designed to be near-permanent edifices for future pilgrimage and offerings. In contemporary societies, battlefields, sites of assassination, mass graves and (often infamous) celebrity death locales have emerged as part of the (post)modern tourist experience, where death becomes a commodity for consumption in a global communications market.[24] As Lennon and Foley maintain, 'In the case of global news media, deaths across the planet can be consumed in the living rooms of the Western world.'[25] Similarly, Tumarkin, for example, has asserted in relation to the Genbaku Dome:

From the second half of the twentieth century, the ruins of Hiroshima, the new universal symbol of destruction, embodied not simply violence but its new limits. Ever since the images and descriptions of the Hiroshima devastation became part of the public imagination, every scene of massive devastation, everywhere in the world, has been inevitably compared to Hiroshima. The Ruins of Hiroshima have become the lens through which other sites of mass destruction and death can be witnessed and remembered.[26]

Just as death and pilgrimage are intrinsically linked to traditions of travel, the self-educative experience of the Enlightenment 'grand tour' and its later commodification via nineteenth-century operators such as Thomas Cook, ensured that the emergence of modern tourism promoted Western colonial ideals of 'universalism, classification and the liberal democratic state.'[27] Whereas today, late industrialisation, immigration, surplus and disposable incomes, alongside modern transport and communications, have all enabled generations of post-war tourists to venture potentially anywhere on the planet. The following 2007 interview with Professor Robert Jacobs at the Genbaku Dome reflects on the contradictory emotions affecting (international) visitors to Hiroshima.

Video 2. Professor Robert Jacobs speaking in front of the Genbaku Dome.

-

According to Lennon and Foley, pilgrimage, or 'thanotourism,' generally conforms to three distinct periods of visitation to death sites. Initially, it is considered socially and culturally acceptable to travel to 'death sites immediately following the events themselves to "show respect" for the dead and mourn.' Secondly, 'for some point of time' thereafter it may be 'unseemly to offer any kind of attempt to interpret events at the site itself—particularly if this involves what can be construed as "exploitation".'[28] Thirdly, it takes significantly longer for an acceptable interpretation of events to be regarded as a legitimate touristic 'experience,' irrespective of how that may be intended. Nevertheless geographical proximity to the place of trauma is essential, according to these authors, yet this last feature is problematic when the site of the visit 'has no direct connection with a "dark" event, but seeks to exploit it for political, social or economic aims.'[29]

-

Ultimately Lennon and Foley define 'dark tourism' as 'an intimation of post-modernity'. This historical and philosophical parameter is essential to understanding the phenomenon. Following Lyotard, the objects of dark tourism themselves serve to introduce 'anxiety and doubt about the project of modernity' and the meta-narratives of legitimation (e.g. the industrial scale of mass death in World War I, the 'rational' planning and execution of Nazi death camps, the catastrophic failure of 'infallible' science and technology along with the contradictions inherent in the Cold War military-industrial complex and national security apparatus).[30] As such, the Manhattan Project and the mass death caused by the use of two atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki inherently qualify within Lennon and Foley's dark tourism criteria.

-

Just as there is a relationship between the spatial proximity of dark tourism to physical sites of trauma and death, the chronological distance is similarly problematic. While ancient battles, plagues, purges and natural disasters are perhaps recalled and memorialised, these events do not 'take place within the memories of those still alive to validate them.' Nor do these historical calamities 'posit questions, or introduce anxiety and doubt about, modernity and its consequences,' let alone seek to commodify such tensions in the interpretation and design of the 'dark' tourist experience.[31] At Hiroshima, the role of hibakusha (bomb-affected people) in mediating visitor experiences, both in person and through recorded testimony, is crucial to preserving this spatio-temporal proximity. However, the generation of survivors of these atomic bombings is rapidly passing. How this transition from embodied, first-hand experience to static, textual and digital mediation will be negotiated in future remains to be seen.[32]

-

The creation of Dark Tourism as a new field of humanistic enquiry has great appeal, yet to date little qualitative or quantitative scholarship yet been produced to compare and contrast tourist behaviour and motivations at various trauma sites internationally and across time. Hence, many observations are anecdotal, neither ethnographic nor sociological. Enquiry into the interactions between tourists, local inhabitants and the geographic and topographic spaces remains underdeveloped.

-

During the course of my visits to Hiroshima, for example, I was intrigued not only by tourist and local behaviour, but also by my own interactions in the observation and recording of others.

Figure 18. The author at the site of the old Yorozuyo Bridge.

For instance, why do I refuse to smile and feel the need to touch this descriptive panel? The bridge has gone and its replacement built in the background. It is the only tactile reminder of this absent artefact. Perhaps my serious pose stems from the site's surreal evocation of a now phantom structure and the counter-intuitive uncanniness of the image—the white 'shadows' of the bridge's guard rail are in fact not shadows at all, but the reverse. It is the texture of the bridge not scorched black from the radiant heat of the atomic detonation; effectively a photo-negative etched into the road surface.

-

Under what circumstances do visitor/tourists at trauma sites consciously modify and/or unconsciously attenuate their behaviour? At another bridge overlooking the river and the Genbaku Dome, when asked by a passing Japanese woman (paralinguistically and by gesture) if I would like to have my photo taken with my friend and colleague, I happily handed over my digital camera and we both posed and smiled as she snapped away. We were cheery and collegial in our demeanour.

Figure 19. Prof. Jacobs and the author across from the Genbaku Dome.

The next day, however, standing directly before the Dome while filming, I (reciprocally) offered to photograph a pair of visiting Norwegian peace activists. In the banter of finding the best angle and asking how they wanted the image framed and in what orientation, one of them suggested that they felt 'odd' smiling, and wondered aloud (in English) if this was inappropriate. Her friend similarly expressed a reluctance to (semi-automatically and impulsively) raise her hand and fingers to gesture the 'V-sign' for peace. The resulting photo seems unnecessarily burdened by a restrained self-consciousness, a sombre inertness that connotes both respect and paralysis. Such complex site behaviours—including a drunken Japanese man at the evening lantern festival on 6 August who was aggressively berating me as a 'gaijin' (a derogatory term for a foreigner) to appalled local onlookers—require a nuanced and comparative methodology that Dark Tourism is embryonically approaching.[33]

Figure 20. Visiting Norwegian peace activists.

Traumascapes/Hauntings

-

Dark Tourism is but one means to evaluate the Hiroshima Peace Park and its new status as official World Heritage Site. Another is to consider the work of Maria Tumarkin and her concept of 'traumascapes'. Tumarkin distinguishes between traumascapes and other places of chaos and catastrophe by their capacity to continually reinvest and haunt the present and the future with a sense of meaning and memory:

Because trauma is contained not in an event as such but in the way this event is experienced, traumascapes become much more than physical settings of tragedies: they emerge as spaces, where events are experienced and re-experienced across time. Full of visual and sensory triggers, capable of eliciting whole palettes of emotions, traumascapes catalyse and shape remembering and reliving of traumatic events. It is through these places that the past, whether buried or laid bare for all to see, continues to inhabit and refashion the present.[34]

One of the strongest associations that lingers, both from my initial visit to Hiroshima and subsequent ones, is the sense of transience and erasure conveyed by the site and encounters around it. The transformative nature of the city is itself foregrounded in the official 'peace' branding and marketing, initiated in 1948 by the Peace City Construction Law.[35] Hiroshima has emerged from its former mercantile status, becoming a military garrison during Japan's colonial conquests in World War Two, then, as dominant icon of the Atomic Age, becoming a reborn, international metropolis and Mecca of peace, advocating nuclear abolition. While these generational transformations of local character mirror a topographic palimpsest, more subtle forms of erasure compete for attention and recognition. The simplicity of the Hiroshima burial mound located within the Peace Park, home to the remains of 70,000+ unidentified victims, is a poignant, silent reminder of mass suffering and death. The tragic erasure evoked here is near genocidal and encompasses not only the eradication of human life, but of identity and history. Those interred human remnants are nameless and without family. According to the official commemorative plaque they were 'discovered in various locations around the city or buried or held in temples and graveyards'.

| |

|

Figures 21 and 22. The Hiroshima burial mound.

|

Directly across the Park is the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. I descended into the cavernous underground chamber with its circular wall mosaic featuring a massive six-metre high, 360 degree view of the devastated city from the hypocentre, with each of the 140,000 mosaic tiles representing a victim of the bomb.

| |

|

Figures 23 and 24. The entrance and mosaic wall at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims.

|

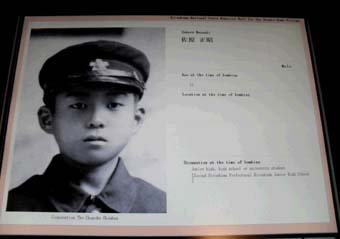

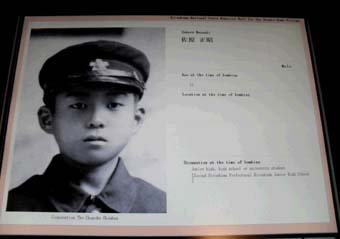

A simple doorway leads visitors to an adjacent bank of video displays that silently post multiple overlapping images of departed Hiroshima citizens (Figures 25–28). I observed most tourists only pausing for a few seconds in front of these flat screens as black and white photos of the old and young, male and female, slowly fade in and out, with terse narrative descriptions assigning name, age and occupation at the time of bombing (e.g. elementary school pupil, factory worker).

| |

|

| |

| |

Figures 25–28. Video displays at the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims.

|

-

After emerging from the mosaic chamber, standing before these video displays, it was shocking to discover that of the 140,000+ fatalities, only 16,289 (to date) have been identified and digitally rendered in this manner. I found in this public space, as I stared into the faces of transient, silent apparitions of lives lived and lost—seemingly trapped in an endless cycle of becoming and erasure—an unmistakably eerie, though respectful aura. It reminded me of Tumarkin's pleas for maintaining memory-work as a 'commitment to remembering and the labour involved in keeping memory undiminished both within our souls and across generations' while avoiding the 'obsession with the heritage of atrocity [that] can turn human beings into victims, divesting them of their complex and rich humanity, of their power and contradictions.'[36]

-

In the Peace Museum basement a temporary exhibition of drawings by senior high school children, created thirty years after the bombing, bares stark testimony to the contradictory notions of memory and erasure. Several of the drawings denote painful recollections, still fresh decades later, of children experiencing unimaginable horror and trauma. In parallel with these indelible memories and graphic depictions is evidence of the atom bomb's capacity to erase identity even amongst survivors. In some pictures witnesses describe their inability to assign gender or age to the staggering, blind, burned, often naked and broken bodies they encounter. Hence, these zombie-like figures—caught somewhere between the uncanny vapourised bodies that left behind vital 'shadows' and the static monuments that commemorate their memory—continue to haunt those who recall them with a sense of indeterminacy and uncertainty. They are frequently described as ghosts or unrecognisably human.

Figure 29. 'I think she was probably a female student but her body was burnt all over preventing her from moving so she had to lay there on her back…I can never erase these memories of those brutal conditions from my memory.'

Figure 29. 'I think she was probably a female student but her body was burnt all over preventing her from moving so she had to lay there on her back…I can never erase these memories of those brutal conditions from my memory.'

|

Figure 30. 'A female student came up out of the river pleading, "Water please, water please," the skin on her face peeling away, stark naked, her hands and feet severely burned, and her skin dropping off…she appeared to be nothing less than a ghost. Oh, her poor soul!!!'

Figure 30. 'A female student came up out of the river pleading, "Water please, water please," the skin on her face peeling away, stark naked, her hands and feet severely burned, and her skin dropping off…she appeared to be nothing less than a ghost. Oh, her poor soul!!!'

| |

Figure 31. 'This female mobilized student was probably doing removal work for building demolition. Severe burns caused her face to swell so greatly that you couldn't tell it was that of a young girl. She too had dreams and aspirations…'

Figure 31. 'This female mobilized student was probably doing removal work for building demolition. Severe burns caused her face to swell so greatly that you couldn't tell it was that of a young girl. She too had dreams and aspirations…'

|

-

In Traumascapes, Tumarkin invokes ghosts, spirits and hauntings as legitimate objects of psycho-sociological phenomena in order to 'study the relationship between trauma and lived geography,' recognising that traumascapes are inherently 'haunting and haunted places.'[37] Most importantly, Tumarkin agrees with Nicholas Abraham's observation that haunting is 'an intergenerational phenomenon'[38]:

We inherit these secrets, the unfinished business of our predecessors. We inherit their histories and their haunted places, on top of which we create our own [?] Whether we care to look or go to great lengths to turn away, traumascapes persist and wield all kinds of powers, and they will continue to do so till we finally take notice of them.[39]

These images and their captions, offered by the hibakusha artists who painted their recollections decades later, refined my troubled gaze onto questions of why so many girls and women were remembered and presented in this manner. This seeming gendered privileging and sacralisation struck me as both harrowing and oddly over-sentimentalised.

Gendered space

Hibakusha women, just like any other human beings, do not want to be pitied or idealized

Maya Todeschina [40]

-

It is not easy, nor perhaps desirable, to assign a prescriptive designation of gender in relation to trauma sites. Indeed, any observations made here are entirely framed by a masculine, Judeo-Christian, first world, Anglo-Celtic perspective. Nevertheless, such impressions may have some worth, no matter their self-consciously post-feminist and diachronic status.

-

Maya Todeschini has suggested, in another context, that there is an 'inseparability of gender from the issue of A-bomb suffering, memory and representation [and] the construction of female survivorhood according to culturally sanctioned norms and normative gender definitions in Japanese society'.[41] Women, according to Todeschini, in film and television representation of hibakusha 'maidens':

seem to represent the persistence of a Japanese past that survives despite modernization and Westernization, embodied in an ahistorical transcendental morality, which places its female guardians 'beyond' politics and history and renders them largely immune to time.[42]

Todeschini asserts women play a central role 'in shaping a larger "politics of memory" surrounding the A-bomb" and its survivors in the collective Japanese memory'[43] where representations of female hibakusha as a 'paragon of tradition contributes to an essentializing view of A-bomb suffering, which…becomes sanctified and frozen into an experience removed from history and politics.'[44]

-

One of the first things that struck me at the Peace Museum, the National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims and throughout much of the Peace Park was that the majority of Japanese present were female. The gender division of labour, traditional or otherwise, was confronting. This included those staff members who facilitated visits by tourists, as well as the presence of pilgrims, guides and park workers (but excluding security staff who appeared to be entirely male). Professor Robert Jacobs pointed out to me, while the Park 'appears' predominantly feminine in character—the Cenotaph and the womb/breast-like Mound—a particular section is populated almost exclusively by (elderly) men.

Figures 32 and 33. Gender divisions are distinctly evident throughout the Peace Park.

-

However, for the most part, various statues and explanatory panels commemorating girls (e.g. Sadako, who died of cancer while attempting to fold one thousand paper cranes) and mothers as 'innocents' tragically killed by the bomb's indiscriminate power are visible throughout the Park.[45] Similarly, in places immediately adjacent to the river, other physical mnemonics commemorating gendered victims (school girls, female office workers) can be found. Among the residents of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 were approximately 8,000 schoolgirls pressed into service, clearing buildings and creating firebreaks to prevent devastation from an anticipated incendiary attack from American bombers dropping napalm (Figures 34–37).

-

In contrast to the officially designated roles and imagery of women, including the elderly hibakusha and the statues, reliefs and sculptures throughout the Peace Park, Todeschini observes an ideological agenda belying the dubious representations of female survivors, one perpetuated by mainstream narratives of selfless, tolerant and stoic sufferers. For Todeschini this deliberate political construction provides an imposing and mythic counter-narrative to wield against those who seek recognition and compensation:

The 'heroic Maiden' is an idealized version of a more threatening reality of dissatisfied, angry, and disempowered women survivors. In their narratives, hibakusha women describe profound feelings of indignation, resentment and injustice; mental alienation and dissatisfaction; gender-based discrimination in marriage and the workplace [and] serious socio-economic difficulties in their attempts to survive materially as single and/or ill women.[46]

Figure 38. Female tour guide.

Figure 38. Female tour guide.

|

|

Figure 39. Hiroshima Peace Volunteer guide.

Figure 39. Hiroshima Peace Volunteer guide.

|

Figure 40. Hibakusha women cleaning in the park.

Figure 40. Hibakusha women cleaning in the park.

| |

Figure 41. Pilgrims at the Cenotaph.

Figure 41. Pilgrims at the Cenotaph.

|

Figure 42. Women attending the burial Mound.

Figure 42. Women attending the burial Mound.

| |

Figure 43. Visitors watching video testimony in the Peace Museum.

Figure 43. Visitors watching video testimony in the Peace Museum.

|

Irrespective of such desires, and concurring with Todeschini, Victor Orr argues: 'the prominence given to women, as symbolic victims of nuclear weapons provided a normative social framework for those of diverse political views to espouse antinuclear pacificism'.[47]

-

It is clear from my visits to Hiroshima that there are distinct and sharply defined gender roles throughout contemporary Japanese society, yet these are not entirely uniform nor without ambiguity. With respect to the memorialisation of girls and women within the Peace Park, and in the roles of city workers and female hibakusha, such demarcations are equally evident and suggest that the observations of Todeschini, Orr others make in relation to gender, Hiroshima and national victimhood, continue to be germane.

Conclusion

-

'Hiroshima', the 'Peace Park' and the 'Genbaku Dome' are deeply complex, contradictory and contested spaces. Creating local, national and international narratives that satisfy competing constituents is patently impossible. However, as a site of contemplation, recollection and suffering—alongside didactic education, propaganda and political expedience—these places evoke a range of emotions and associations.

-

Despite the potential for such postures and activities to re-traumatise and haunt first, second and third generation hibakusha, as Lisa Yoneyama has noted:

Rather than suppressing the differences that inevitably arise around any site of commemoration, Hiroshima's memorial icons have, for the most part, fruitfully allowed space and occasions for such differences to be aired and for difficult issues to be debated openly.[48]

-

So, at any given time in Hiroshima, amongst the ebb and flow of daily cosmopolitan life around the Genbaku Dome and the Peace Park, one might find yakuza thugs intimidating city officials, monks chanting for peace, visiting Japanese and international pilgrims, anti-nuclear protesters, performance artists, film crews, jazz ensembles, and extremist right-wing political parties advocating the acquisition of nuclear weapons. In a city that aggressively promotes and brands itself as reborn, phoenix-like from the atomic ashes, to warn and educate the world about the dangers of nuclear weapons, surprisingly, such political antagonisms are tolerated and accommodated by the civic pluralism that permeates Hiroshima.

Endnotes

[1] John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster, London: Continuum, 2000; Phillip R. Stone, 'Introducing Dark Tourism', The Dark Tourism Forum, 2006, URL: www.dark-tourism.org.uk/, site accessed 3 May 2009; Stone, 'A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions,' in Tourism, an Interdisciplinary International Journal, vol. 54, no. 2 (2006), pp. 145–60, URL: www.dark-tourism.org.uk/, site accessed 3 May 2009.

[2] The following observations are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of those organisations.

[3] Unless noted all photos are by the author.

[4] Richard Rhodes, Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb, New York: Touchstone, 1995, p. 21.

[5] Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, New York: Simon & Schuster, [1]986.

[6] Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, p. 711.

[7] Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 2.

[8] UNESCO, 'Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome)', p. 115, URL: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/775/, site accessed 3 May 2009.

[9] Barefoot Gen, Dir: Nakazawa Keiji, 1983.

[10] Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, p. 715.

[11] Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, p. 728.

[12] Akira Lippert, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005, pp. 93–94.

[13] Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, p. 711

[14] Maria Tumarkin, Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Transformed by Tragedy, Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2005, p. 8. Tumarkin broadly defines 'traumascapes' as: 'not another, catchier, word for a site of tragedy, because 'trauma' itself is not another word for tragedy and disaster' (p. 11). She argues traumascapes 'become much more than physical settings of tragedies: they emerge as spaces, where events are experienced and re-experienced across time. Full of visual and sensory triggers, capable of eliciting whole palettes of emotions, traumascapes catalyse and shape remembering and reliving of traumatic events. It is through these places that the past, whether buried or laid bare for all to see, continues to inhabit and refashion the present' (p. 12). She adds that traumascapes 'are a distinctive category of place, transformed physically and psychically by suffering [and are] precisely the places that remind us that the past cannot simply be erased, or for that matter, simply reconstructed' (p. 18).

[15] Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces, pp. 37–38.

[16] Owen Beazley, 'A paradox of peace: the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) as World Heritage,' in A Fearsome Heritage: Diverse legacies of the Cold War, ed. John Schofield and Wayne Cocroft, Walnut Creek CA: Left Coast Press, 2007, pp. 33–50.

[17] UNESCO, 'Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome),' Annex V, URL: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/repco96x.htm, site accessed 3 May 2009.

[18] Beazley, 'A paradox of peace,' p. 40.

[19] UNESCO, 'Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome)', p. 117, URL: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/775/, site accessed 3 May 2009.

[20] Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces, p. 3.

[21] Lennon and Foley, Dark Tourism , p. 3.

[22] Lennon and Foley, Dark Tourism, p. 4.

[23] As discussed, the Hiroshima anniversary dates coincide with the traumatic Japanese surrender. At the same time, Obon, the annual Buddhist Festival of the Souls runs from 13–16 August, commemorating family, departed loved ones and the ritual return journey of the dead by floating lanterns out to sea. This ceremony is also the evening highlight from the 6 August Hiroshima Day activities.

[24] Stone, 'A dark tourism spectrum.'

[25] Lennon and Foley, Dark Tourism, pp. 5–6.

[26] Tumarkin, Traumascapes, p. 186.

[27] Lennon and Foley, Dark Tourism, p. 7.

[28] On the problematics of exploiting trauma sites, see, for example, Dana Heller (ed.), The Selling of 9/11, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

[29] Lennon & Foley cite the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, which has 'no direct spatial link with the Jewish Holocaust' yet attracts up to 2.5 million visitors per annum (see Dark Tourism, p. 10.

[30] Please reference Lyotard

[31] Lennon & Foley, Dark Tourism, p. 12.

[32] The Genbaku Dome and the peace park are now undergoing computer 3D modelling by Japanese and US artists. 'American special effects masters join effort to reconstruct Hiroshima in CG,' Mainichi Daily News, Japan, November 3, 2009, URL: http://mdn.mainichi.jp/mdnnews/news/20091103p2a00m0na015000c.html, site accessed 5 November 2009.

[33] Stone, 'Introducing Dark Tourism.'

[34] Tumarkin, Traumascapes, p. 11.

[35] Yoneyama, 'Remembering and imagining the nuclear annihilation in Hiroshima,' Conservation at the Getty Newsletter, Summer 2002, URL: http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications/newsletters/17_2/news_in_cons1.html, site accessed 3 May 2009.

[36] Tukmarkin, Traumascapes, p. 202.

[37] Tumarkin, Traumascapes, p. 232.

[38] Tukmarkin, Traumascapes, p. 235.

[39] Tukmarkin, Traumascapes, p. 235

[40] Maya Morioka Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden": Female Hibakusha as Cultural Heroines, and the politics of A-bomb Memory,' in Hibakusha Cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Nuclear Image in Japanese Film, ed. Mick Broderick, London: Kegan Paul International, 1996, pp. 222–52.

[41] Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden,"' p. 222.

[42] Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden,"' p. 243.

[43] Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden,"' p. 222.

[44] Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden,"' p. 242.

[45] For details of the contradictions between Truman's public utterances and private concerns regarding women and children being killed indiscriminately see, Doug Long, 'Hiroshima: Harry S. Truman's Diaries and Papers':

[8/10/45: Having received reports and photographs of the effects of the Hiroshima bomb, Truman ordered a halt to further atomic bombings. Sec. of Commerce Henry Wallace recorded in his diary on the 10th, 'Truman said he had given orders to stop atomic bombing. He said the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible. He didn't like the idea of killing, as he said, "all those kids".'

John Blum, ed., 'The Price of Vision: the Diary of Henry A. Wallace, 1942-1946', pp. 473–74, and: 'My object is to save as many American lives as possible but I also have a humane feeling for the women and children in Japan.' Barton Bernstein, Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory, Diplomatic History, Spring 1995, material quoted from pp. 267–68), URL: http://www.doug-long.com/hst.htm, site accessed 5 November 2009. On July 21, 1948 Truman confided some other private thoughts on the atomic bomb to his staff. Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission David Lilienthal recorded Truman's words in his diary that night, along with Lilienthal's own observations in parentheses: 'I don't think we ought to use this thing [the A-Bomb] unless we absolutely have to. It is a terrible thing to order the use of something that (here he looked down at his desk, rather reflectively) that is so terribly destructive, destructive beyond anything we have ever had. You have got to understand that this isn't a military weapon. (I shall never forget this particular expression). It is used to wipe out women and children and unarmed people, and not for military uses.' (David Lilienthal, The Journals of David E. Lilienthal, Vol. Two, pp. 391) [my emphasis – Doug Long], URL: http://www.doug-long.com/rambling.htm#deserveit, site accessed 5 November 2009.

[46] Todeschini, '"Death and the Maiden,"' p. 244.

[47] James J. Orr, The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 58.

[48] Yoneyama, 'Remembering and imagining the nuclear annihilation in Hiroshima.'

|

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Figure 7. Photo by Robert Jacobs

Figure 7. Photo by Robert Jacobs

Figure 29. 'I think she was probably a female student but her body was burnt all over preventing her from moving so she had to lay there on her back…I can never erase these memories of those brutal conditions from my memory.'

Figure 29. 'I think she was probably a female student but her body was burnt all over preventing her from moving so she had to lay there on her back…I can never erase these memories of those brutal conditions from my memory.'

Figure 30. 'A female student came up out of the river pleading, "Water please, water please," the skin on her face peeling away, stark naked, her hands and feet severely burned, and her skin dropping off…she appeared to be nothing less than a ghost. Oh, her poor soul!!!'

Figure 30. 'A female student came up out of the river pleading, "Water please, water please," the skin on her face peeling away, stark naked, her hands and feet severely burned, and her skin dropping off…she appeared to be nothing less than a ghost. Oh, her poor soul!!!'

Figure 31. 'This female mobilized student was probably doing removal work for building demolition. Severe burns caused her face to swell so greatly that you couldn't tell it was that of a young girl. She too had dreams and aspirations…'

Figure 31. 'This female mobilized student was probably doing removal work for building demolition. Severe burns caused her face to swell so greatly that you couldn't tell it was that of a young girl. She too had dreams and aspirations…'

Figure 38. Female tour guide.

Figure 38. Female tour guide. Figure 39. Hiroshima Peace Volunteer guide.

Figure 39. Hiroshima Peace Volunteer guide. Figure 40. Hibakusha women cleaning in the park.

Figure 40. Hibakusha women cleaning in the park. Figure 41. Pilgrims at the Cenotaph.

Figure 41. Pilgrims at the Cenotaph. Figure 42. Women attending the burial Mound.

Figure 42. Women attending the burial Mound. Figure 43. Visitors watching video testimony in the Peace Museum.

Figure 43. Visitors watching video testimony in the Peace Museum.