'Dancing Through' Historical Trauma:

Okinawan Performance in Post-Imperial Japan

Valerie H. Barske[1]

Introduction: setting the stage

-

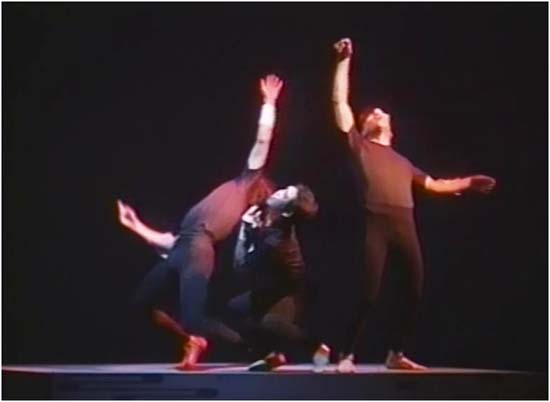

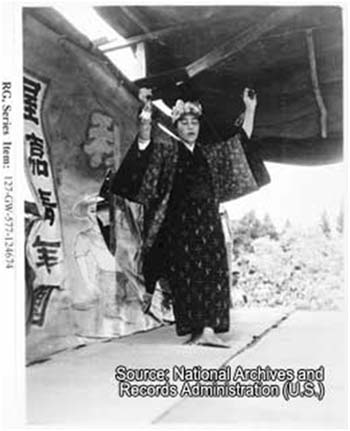

In a dark theatre, sounds of WWII fighter planes and B-52 bombers whirl in the distance. Faint shots grow louder–BAM! The light from a violent explosion shines on the hidari gomon, symbol of the Ryukyu Kingdom.

Figure 1. Opening Scene of Ruten. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.[2]

Figure 1. Opening Scene of Ruten. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.[2]

|

An American military commander speaking broken Japanese echoes, 'detekoi, detekoi' (Come out, come out!). On stage, three young men collapse to the ground under continued gunfire, embodying a war memorial for Okinawan boys recruited to fight for imperial Japan.

Figure 2. Actors re-embody Kenji no Tō. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figure 2. Actors re-embody Kenji no Tō. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

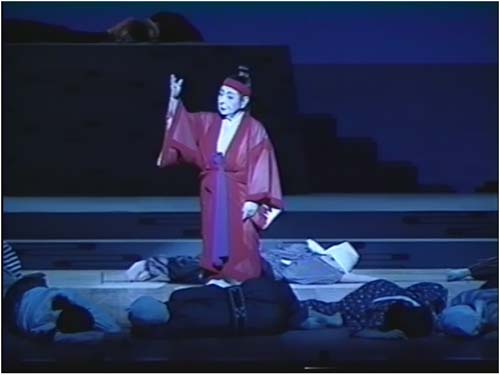

As the dead bodies fade into a red glow, the scene flashes back to the seventh century. When the spotlight closes in, Kodama Kiyoko appears at the center of the stage as the 'shima no seishin' (island spirit) of Okinawa.[3] Holding a deigo tree branch, the official flower of Okinawa Prefecture, she begins to dance through 1300 years of historical wounds that have afflicted the people of Okinawa.

Figure 3. Kodama Dancing with the Deigo Branch. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figure 3. Kodama Dancing with the Deigo Branch. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

-

Only days after the US Occupation ended with the official return of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty on 15 May 1972, the Tokyo Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society debuted this theatrical piece entitled Ruten Okinawa (Okinawa in Flux).[4] As the opening scene suggests, Ruten Okinawa highlights traumatic memories and painful political realities that continued to resonate in post-imperial Japan. Beginning with the earliest records of the Ryukyu Islands, this historical dance drama traces tragic moments in Okinawa's past. Specific scenes depict the Satsuma invasion of 1609, the colonising conquering of the Ryukyus under imperial Japan in 1879, the WWII Battle of Okinawa, and the unequal terms of Reversion to Japan that maintained the US military presence in Okinawa following 1972. The piece features Okinawan playwright, performer and choreographer, Kodama Kiyoko (1914–2005), embodying the personification of the 'island spirit.'[5] Trained under dance master Tokashiki Shūryō (1880–1953), Kodama made history by becoming the first woman to head one of the last three remaining Okinawan performance lineages to survive the war.[6] Along with countless awards for the artistic quality of her dancing, she received special recognition from the Okinawa Prefectural Government in November 2005 for her lifetime achievements in cultural preservation and the promotion of Okinawan dance traditions.[7] Throughout her career, Kodama utilised the performing arts as a vehicle for engaging with historical debates over war memory, trauma, peace activism, ethnicity, cultural preservation and national identity.

-

This article discusses the appropriation of Okinawan performance traditions as critical cultural processes for coping with historical trauma in post-imperial Japan. In particular, it traces Kodama Kiyoko and her works in the broader context of how performance traditions intersect with Okinawan experiences of colonial modernity, war atrocities, and lingering legacies of imperialism. In the struggle for Okinawan Reversion, the performing arts represented a way of culturally re-uniting Okinawa with Japan by rewriting historical narratives of the past and redefining post-imperial Japanese culture as inclusive of Okinawan ethnic difference. Within this framework, Kodama Kiyoko's 1973 re-staging of Ruten Okinawa represents a meaningful site for understanding the use of performance to cope with ongoing experiences of trauma in Okinawa. Based on archival and oral history research, this article presents a preliminary analysis of how Kodama reclaims gendered performance traditions to confront historical narratives as a form of embodied cultural healing. It argues that through an empowering portrayal of Okinawa's feminine island spirit, Kodama offers new possibilities for living with the past by 'dancing through' trauma in the post-imperial era.

-

Recent work in trauma studies has challenged scholars to move beyond standard historiography in 'writing about trauma.' Dominick LaCapra separates collective trauma into two categories: 1) 'acting out,' a form of 'dehistoricized nostalgia' that repeats traumatic events and 2) 'working through,' which incorporates 'cultural practices that allow for historicization, mourning, and transformative memory work.'[8] Moving from 'acting out' to 'working through,' LaCapra notes the importance of 'performative modes including ritual, song, and dance,' which allow for 'more viable articulations of experience.'[9] He argues that in order for historians 'to do justice' to trauma, they may need to engage in 'extended close reading of a work of art,' a novel, a poem, a film, a painting or a performance, even if this reading takes them 'outside recognizable forms of historiography.' [10] LaCapra highlights 'painting and even dance' as possessing critical post-traumatic dimensions for 'coming to terms in different ways with the traumas that called them into existence.' [11]

-

This article examines the process of 'working through' and 'coming-to-terms' by interrogating the intersections of trauma, performance and history. Its focus on performance is precisely to emphasise how people actively cope with the past and construct their worlds through signifying actions and embodied practices. For dealing with trauma, performance becomes a crucial historical site, an alternative archive in which a group reforms collective identity and constructs meaning anew. Analysing traumatic histories in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Rebecca Saunders and Kamran Aghaie criticise the state of 'trauma studies' as a field 'grounded in the events and processes of Western modernity.'[12] They challenge the privileging of narrative or cognitive approaches for coping with trauma over 'affective integration' in which 'embodied practices of dance, song, lamentation, and dramatic reenactment may offer a sense of environmental control, empowerment, or communality unachievable through language alone.'[13] Saunders and Aghaie also problematise the gendered division of labor in mourning and memory work that assigns men the role of 'officially memorializing and recording history,' while women are charged with 'caring for the dead and leading communal mourning rituals.'[14] As in the case of Kodama Kiyoko, women may also employ embodied practices in alternative tellings that both record history and provide communal care. While performance may not be able to 'cure' collective trauma, it may reconfigure or remediate experience to provide a form of cultural healing and new ways of living with trauma.

-

Scholarship on trauma in postwar Japanese history often extends Western diagnostic categories of the traumatic to the narratives of hibakusha survivors of the atomic bombs. For example, psycho-historian Robert Jay Lifton draws comparisons with European Holocaust survivors to analyse trauma in hibakusha experiences.[15] He discusses the struggle survivors face in moving beyond a state of psychic numbing or muteness in order to find formulations for articulating their experiences. Lifton interviewed survivor-artists such as Ota Yōko for whom the process of articulating trauma included searching for authenticity and the right to imagination through literary forms.[16] Based on his categories of analysis, Lifton concludes that Ota remains imprisoned in her A-bomb experience, which limits her literary creativity. Lisa Yoneyama argues that Lifton's 'focus on ?psychological efforts" results in only a limited explanation.' In contrast, she attempts to highlight the 'intersecting works of power that tend to be ignored.'[17] She also questions the validity of analogies between imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. Yoneyama argues that in contrast to more critical views of Nazi actions, narratives of war in Japan are dominated by the perception that 'ordinary Japanese people had been the passive victims of historical conditions.'[18] She challenges this view of passive victimisation by discussing resident Koreans and the endurance of colonial memories in the postwar era.

-

Building on Yoneyama and other reexaminations of trauma lingering in the wake of Japan's empire, post-WWII performance in Okinawa may be understood as a means of engaging with the tensions of trauma inherent in 'post-imperial Japan.' The epochal appellation of 'post-imperial' marks the fact that the legacy of Japanese imperialism continues to haunt cultural terrains long after the formal end of empire in 1945. In this context, the recuperation of Okinawan performance, formerly suppressed by the structures of colonial modernity, empowers a reclaiming of historical agency, allowing Okinawans to dance their own histories into being. The dancing of trauma as history transcends gendered victimisation narratives that deny Okinawans historical subjectivities and reduce them to feminised colonial others. Thus, this article attempts to disrupt official narratives of trauma in Japan by recasting the past through the lens of Kodama Kiyoko, a female ethnic minority and former colonial subject whose personal stories illustrate the meaning-making power of Okinawan performance. With the revival of performance forms as a symbol of cultural and physical survival more generally, Okinawan dancing creates an embodied 'alternative historiography,' which aids in the defeat of the disabling aspects of trauma that may render an oppressed population immovable. [19] Performers, playwrights, and activists in Okinawa overcome the potential paralysis of trauma repeating by 'working through' or in many cases 'dancing through' multi-modal experiences of the past.

Dancing through colonial modernity

-

As Japan in the Meiji era (1868–1912) began creating a modern imperial nation, the Ryukyu Kingdom became one of the first foreign spaces to be occupied by Japanese military forces and subordinated under a Japanese governorship. In addition to securing Shuri Castle with Japanese troops and forcibly exiling King Shō Tai, the colonising policy of Disposing of the Ryukyus (Ryūkyū shobun) sought to destroy Ryukyu court culture and social practices, particularly any remnants of the kingdom's former relations with China. This process to assimilate Ryukyuans made the performance of traditional Ryukyu court dances and female-centered religious rituals illegal. Dance magistrates and performers but also priestesses and shamans were banned from practising their embodied traditions.[20] In this context, Meiji officials viewed the act of dancing in Okinawa as a threat to nation-building and imperial expansion.

-

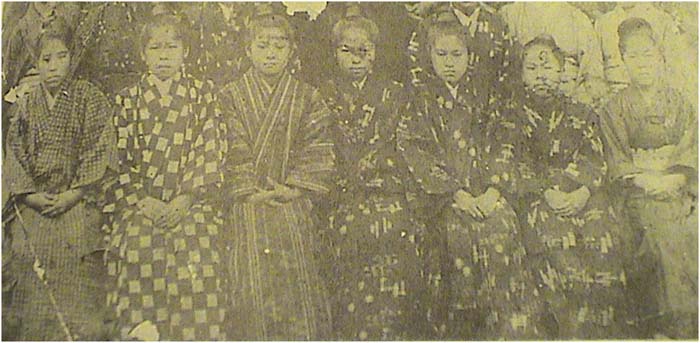

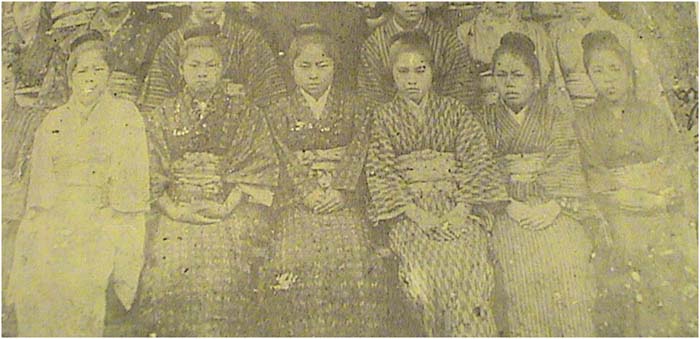

By the Taisho era (1912–1926), top-down assimilation practices promoted by mainland Japanese colonial policies were promoted through Social Customs Reforms (fūzoku kairyō) that specifically targeted women's bodies, female gendered folk practices, and women with spiritual powers such as yuta shamanic healers. Through the imperial education system, girls were forbidden to wear Ryukyuan clothes (ryūso) and hairstyles.

Figures 4 and 5. Early twentieth century photos of Okinawan school girls wearing Ryukyuan clothes [top] versus Japanese clothes [bottom], both photos were taken on the same day to show how the girls were required to change their dress in the early twentieth century. Source: Hokama Yoneko, Jidai o irodotta onnatachi: Kindai Okinawa joseishi, Naha: Niraisha, 1996, p. 210.

Figures 4 and 5. Early twentieth century photos of Okinawan school girls wearing Ryukyuan clothes [top] versus Japanese clothes [bottom], both photos were taken on the same day to show how the girls were required to change their dress in the early twentieth century. Source: Hokama Yoneko, Jidai o irodotta onnatachi: Kindai Okinawa joseishi, Naha: Niraisha, 1996, p. 210.

|

They were also forbidden to learn or perform folk dances at school, and engage in other customary rites such as tattooing of women's hands, hajichi.

Figure 6. Photograph from 1919 of a young woman being tattooed with Okinawan hajichi, a practice outlawed in 1899. Source: Saito Takushi, Irezumi bokufu: Naze irezumi to ikiru ka,Yokohama: Shunpu sha, 2005, p.174.[21]

Figure 6. Photograph from 1919 of a young woman being tattooed with Okinawan hajichi, a practice outlawed in 1899. Source: Saito Takushi, Irezumi bokufu: Naze irezumi to ikiru ka,Yokohama: Shunpu sha, 2005, p.174.[21]

|

-

Young women were also specifically discouraged from participating in mō ashibi (field play) or yoru ashibi (night play), under the assumption that the young women would reform the men.[22] Gathering in the fields after a long day's work, young men played folk songs while the young women danced; reportedly they then paired off into couples to have sex in the fields. Social Customs Reform Associations in local villages attacked these practices as working against modernisation, promoting an image of Okinawans as backward, lazy, and sexually promiscuous.

-

Despite these processes of colonial modernity that sought to eradicate many folk traditions, local dances continued, especially through the Okinawan equivalent of obon ancestral celebrations.[23] Born on the island of Kumejima in 1914, Kodama Kiyoko (née Nakandakari Kiyo) recalls folk performances throughout her childhood during the mid-Taisho era. Kodama remembers repeating the chants of ritual performers, but she was not allowed to receive formal training in classical Ryukyuan dances.[24] Through the general policy for Disposing of the Ryukyus (1879) and the Decree for Controlling Play Performances (1882), Japan's imperial laws censored and restricted the performance of local dances in Okinawa. Biologically-female performers continued to be banned from appearing on stage in public except in the licensed prostitution quarters of Tsuji.[25]

-

Throughout the early 1900s, colonial economic structures created land scarcity, job shortages, and overall poverty in Okinawa, forcing many people to either emigrate permanently or serve as migrant workers abroad for limited periods.[26] The intensity of Social Custom Reforms also reflected the need for Okinawans culturally to pass in mainland Japan and other parts of the empire where they might seek work. This pressure to pass as Japanese often led to Okinawan attempts at changing their physical appearance, speech patterns, bodily movements, and personal names. Kodama's mother changed her family name in 1927 to the more Japanese pronunciation Nakamura in order to avoid discrimination as a dekasegi (migrant worker) in Fukuoka. Eventually when she joined her mother in Kyushu to begin training as a nurse for the Japanese imperial government, Kodama added the Japanese suffix '-ko' to her first name.[27] In 1934, she was deployed to work for a hospital on the South Seas island of Truk, which served as a central base for the southern expansion of Japanese imperialism.[28] As Tomiyama Ichirō explains, 'much of the necessary labor power for colonial management' in the South Sea Islands 'was brought in from Okinawa.'[29]

-

From the perspective of mainland colonists such as Yanaihara Tadao, Okinawans contributed to the failure of colonial efforts in the South Seas due to their 'shabby' lifestyle, typified by their 'unintelligible' music and 'coarse' dancing. By 1942, imperial policies no longer allowed Okinawans, viewed as not properly civilised, to emigrate to Palau and other South Seas islands.[30] At the same time, the Japanese governor in Okinawa, Fuchigami Fusatarō, reiterated a ban on anything 'Ryukyuan' in the imperial education system, including songs, dances, or traditional dress.[31] Despite official limitations placed on Okinawan emigration, Okinawans still sought work throughout the greater empire. For instance, Kodama's sister had joined other settlers hoping to improve their socio-economic situation in Manchuria. Kodama finished her time in Truk and intended to make a short trip to Manchuria, but with the intensification of military violence, she was not able to return to Okinawa until years after the war. She worked as a nurse in Dalian for the Japanese?controlled South Manchuria Railway Hospital. In 1945, before the war ended, Kodama left Manchuria for mainland Japan briefly to marry Kodama Keisuke, thereafter taking his name.[32] Unfortunately, both Keisuke and her sister's husband died in the war.

-

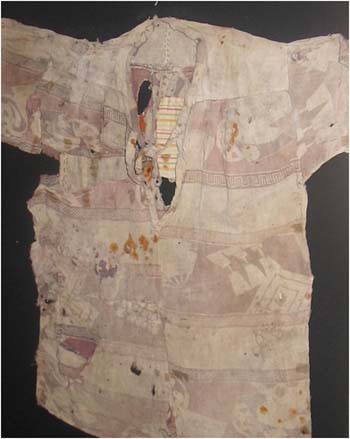

Individual loss of Okinawans throughout the empire accompanied the larger realities of collective trauma throughout wartime Okinawa, where people experienced all levels of physical, emotional and cultural loss in WWII. Okinawan citizens participated in the war effort as drafted and volunteer soldiers, conscripted laborers,

|

sexual slaves and civilian imperial subjects.[33] From the first air bombings on 10 October 1944 until the final surrender by Japanese forces on 7 September 1945, an estimated 200,000 Okinawan civilians died in the greater Battle of Okinawa (officially dated April 1–June 23 1945).[34] Roughly 400,000 Okinawans, displaced from their homes, were living in caves or moving from location to location across the island, searching for scraps of food in abandoned fields. While dodging US air raids, many Okinawans perished at the hands of Japanese soldiers. A young boy on the island of Iejima was stabbed to death by a Japanese soldier who feared the child's crying would reveal his position to the enemy. Others were punished by death for speaking their local dialects, an act that suggested disloyalty or espionage. On Kodama's home island of Kumejima, the Japanese army massacred twenty civilians including women and children for spying and other charges after the surrender of Japanese forces in Okinawa (beginning June 25, 1945).[35]

Figure 7. Photo of a young Okinawan boy's shirt stained with blood. Source: Photo by author taken at the Nuchi dū takara no ie, Treasure of Life Itself Citizen Museum in Iejima, October 2005).

|

-

Drawing from imperial ideologies promoted through the National Mobilisation Law (1938), the policy on Imperial Assistance Associations (1940), and the general senjinkun (wartime code of actions), the 32nd Army division of Japan encouraged Okinawans to kill themselves rather than suffer the dishonor of being captured by US troops. The Japanese military distributed hand grenades for compulsory mass suicides, which occurred in locations such as Yomitan, Iejima, Kerama, Zamami, and Tokashiki. Nearly 1500 young boys were recruited to fight with the Blood and Iron Corps, while more than 220 young girls served in the Himeyuri Corps as battlefield nurses. When the battle intensified, Japanese troops 'sacrificed' these nurses by disbanding their corps, forcing them to flee and fend for themselves in the midst of intense US bombing; roughly 219 nurses died.[36] An estimated 1500–2000 Okinawans shared the fate of other colonial women from Korea, China and the Philippines who were forcibly recruited into Japan's institutionalised system of sexual slavery.[37] Overall, Okinawans experienced a form of hell on earth, which some claim resulted from Okinawa's ambiguous colonial status within the Japanese empire. Firsthand accounts of wartime atrocities in Okinawa emphasise not only the loss of life, but other forms of war casualties including loss of bodily functions, cultural loss and the denigration of humanity.[38]

Performing postwar trauma

-

Before the Battle of Okinawa officially ended, the 'postwar' began for most Okinawans on the day they were herded into American refugee camps. In this immediate aftermath of war, Okinawan refugees employed folk music and dancing to restore some sense of humanity, normalcy and community to life in the camps. They constructed makeshift musical instruments out of scrap materials, empty SPAM tin cans, parachute strings, parachute cloth, pieces of wood from old bed posts, etc.

Figure 8. Image of a tin can sanshin at the Treasure of Life Itself museum in Iejima. The caption explains that the kankara sanshin healed pain and suffering of the war and empowered people with the strength to live. Source: Photo by author, October 2005.

Figure 8. Image of a tin can sanshin at the Treasure of Life Itself museum in Iejima. The caption explains that the kankara sanshin healed pain and suffering of the war and empowered people with the strength to live. Source: Photo by author, October 2005.

|

With these kankara sanshin (tin can three-stringed instrument), refugees sang established minyō (folk songs), but also composed new lyrics about war trauma, loss, and pain in their current situation. The songs focused on nostalgic feelings for earlier times in Okinawa, regretting the realities of Okinawa as a battlefield. For example, the Okinawan refugee songs told of the mountains and fields engulfed in flames, and how the sea became the sole place for refuge, food, and life.[39]

-

These songs that encapsulated the hardships of daily life in the camps became known as yaka bushi, songs from the Yaka refugee camp, or PW mujō (prisoner of war songs). The camp songs and dances served as a crucial medium for beginning to convey wartime experiences, creating an embodied counter-telling to official narratives, but also for coping with life as postwar refugees unable to return home. Okinawans living 'everyday with the loss of their homes, separated from their parents and brothers and sisters' relied on 'sanshin songs and dances' in order to express their 'happiness to be alive.'[40] Nakamura Fumiko remembers, 'when I heard the sound of that sanshin in the midst of all the disaster, I got choked up. ?At least the Okinawan spirit wasn't completely destroyed by the war," I said to myself.'[41]

-

According to war survivor and activist Taira Osamu, it was through yaka bushi (refugee camp songs)

|

that Okinawans first started articulating the atrocities of war and their own desires for peace. Matayoshi Shizue recalls that as people gathered, someone who knew how to dance would perform for everyone, helping to ease feelings of 'loneliness and hardship.'[42] Complementing yaka bushi, classical Ryukyuan dances and Okinawan theatrical dramas were also revitalised in the camps as a literal revival of culture (bungei fukkō), symbolic of the continuation of life. Encouraged by the cultural propaganda of the US to re-Ryukyuanise Okinawa, as early as mid-April 1945, Okinawans staged dances and theatrical performances in open-air theatres.

Figure 9. Iha Setsu performs a traditional women's Ryukyu court dance, yotsu dake, at the Ishikawa refugee camp 11 June 1945. Source: Okinawan Prefectural Archives, Digital Image Archive.

|

-

Goeku Chōshō and Matayoshi Kowa, members of the Okinawa Advisory Council to the US administration in Okinawa, assembled performers in August 1945 to form the Okinawa Performing Arts Federation. As they toured the refugee camps, they performed well-known Ryukyu court dances, scenes from Okinawan kumiodori dance dramas, and classic musical pieces.[43] Wauke Tomiko, a high school girl at the time, describes the theatrical performances in the camps as 'unforgettable,' 'in the middle of the colorless daily life of a refugee, only the world of Okinawan plays had dreams that appeared bright and cheerful.'[44] Gushiken Kōsei, then a young boy, adds that with the intimate atmosphere of the small roten gekijō (open-air theatres), watching these performances was the first time since before the war that people felt a sense of ittaikan, of belonging and identity.[45] This sense of shared identity based on collective experiences of war, colonial violence and trauma began to be articulated through performance as a cultural medium of healing and a symbol of anti-war sentiments in Okinawa.

-

The performing arts also served as a means of recovery for displaced Okinawans throughout the empire, unable to return home after the destruction of the war. In 1946, Kodama and her sister remained trapped in Kagoshima where she met her future benefactor and teacher, Tokashiki Shūryō. Trained under the Ryukyu court performer Matsushima Pēchin who died in 1900, Tokashiki was one of the sandai shishō (three masters) of traditional performance. Kodama described how she came to know Tokashiki in Kagoshima:

It was the end of the war, there was nothing to eat, everyone was looking for sweet potatoes. It was a difficult time. Someone found out that I could dance and went to Tokashiki saying, 'Kodama is really good at dancing'. Eventually, Tokashiki found me and said, 'why not dance, even just a bit, let's dance. Everyone is sad and lonely, people want to return to Okinawa. We are all so lonely, so let's dance.'[46]

Kodama agreed to dance, partly in response to her own sense of longing and mourning for Okinawa. Similar to the refugees on the island of Okinawa, Okinawans in Kagoshima utilised dancing to express their grief and their desire to recreate a sense of home. Kodama's experiences in Kagoshima echoed the touring performers from Okinawan refugee camps. She remembers performing in an outdoor theatre with Tokashiki playing on a borrowed sanshin made of parachute materials.

-

After performing together for nearly two years, Tokashiki and Kodama were approached by the Okinawa Foundation to create the first Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society. Tokashiki served as the head dance master and mainland ethnologists such as Origuchi Shinobu (1887–1953)functioned as advising members. The Society invited Kodama to pen their mission statement. Recalling the devastation and chaos of the immediate postwar, Kodama writes:

Never in our lives have the performance skills of our Okinawan ancestors and the preservation of Okinawan performing arts been more urgent than today. Under the Occupation of America, where language and culture are completely different, in addition to the present state of affairs where people are losing themselves due to the fear of war, confusion in everyday life, and the fear of losing precious traditions forever, Okinawans find a sense of pride in our past.[47]

She adds that in the aftermath of war, Okinawans answered worldwide calls for peace by revitalising classical music and dance forms that embody 'peace-loving Okinawa.' Through this particular phrasing, Kodama participates in discourses of postwar Okinawa that transformed individual narratives of trauma into a group identity defined by an inherent peacefulness, which is exemplified in performance traditions.

-

In spite of official efforts to revive 'Ryukyuan' cultural practices, in part by supporting dancers, actors, and musicians under the US Occupation, a popular movement for Reversion to Japan gained momentum across Okinawa by the 1950s.[48] Trauma in the postwar era began to be reconfigured as not only resulting from wartime experiences, but also from new forms of colonial oppression of the US Occupation. Many Okinawans were particularly incited to revert after Okinawa remained under US rule both in April 1952, when the rest of Japan was liberated, and in August 1953, when the Amami Oshima Islands returned to Japan. Arasaki Moriteru recalls encountering the reality of his complex Okinawan identity when he could not join his Tokyo classmates in performing the embodied action of banzai to celebrate Japan's liberation.[49] While most historical accounts emphasise the political aspects of this movement, dominated by activists, landowners, labourers and students, Reversion also involved a crucial cultural component.[50] Dancers, actors,

|

musicians and other performance artists mobilised to promote a sense of historical and cultural unity with the 'fatherland' of Japan. Some of the same women's dances such as yanagi (willow dance) and nufa-bushi (flower hat dance), Ryukyu court dances that were forbidden under Japan's assimilation practices, then celebrated through the cultural propaganda of the US Occupation, were also re-appropriated in the struggle for returning to Japan.

Figure 10. Yanagi willow dance stamp, issued by United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyus in 1956 to celebrate the 'national dances' of the Ryukyu Islands. Source: Author's personal collection and photo.

|

-

In order to prepare for hondo ittaika (unifying with the mainland), Okinawans sought to popularise the Reversion Movement by demonstrating the successful revival of the arts to mainland audiences.[51] As part of the eighth Ministry of Education and Culture Arts Festival in Japan, held in November 1953, Okinawan stars such as Tamagusuku Seigi, Shimabuku Kōyū, and Miyagi Shishō presented classical Ryukyuan dances, music, and theatrical pieces to symbolise unity with Japan. Videotaped and later broadcast across Japan on the national television station NHK, this performance was also appropriated by mainland Japanese Reversion supporters to reinforce Okinawa's connection to Japan. Commenting on the Okinawan dancers at the Arts Festival, mainland Japanese ethnologist Honda Yasuji declared that the 'fushigina miryoku' (mysterious charm) of the Okinawan performing arts is actually the same charm found in ancient mainland arts that expressed 'the spirit of [our] Japan's ancestors.'[52] Honda's statement reiterates the colonising logic of prewar imperial Japan, which justified Japanese rule by promoting the image of a shared cultural history and racial ties between Okinawa and Japan. Honda recuperates the performing arts in service of naturalising Okinawa as always already part of Japan's cultural history.

-

Recognising that wartime trauma and postwar tragedies could not be healed while the US Occupation continued, many performers donated their time as volunteer activists striving for Reversion to Japanese Sovereignty. Kodama joined other performers from Okinawa and mainland Japan working with the Southern Fellow Countrymen Support Society at various events between 1958 and 1963. She toured Japan with this group from Fukuoka, to Osaka, all the way north to Sapporo, appealing to mainland audiences to win popular support for Reversion. However, by the late 1960s, even the most fervent Reversionists began to challenge US and Japanese plans to orchestrate a return without much concern for Okinawan voices, effectively maintaining the postwar status quo with regard to the military presence of the United States. While the US and Japanese governments determined the specific terms of Reversion at the Sato-Nixon Summit of October 1969, a group known as the Han Fukki Kaigi (Anti-Reversion Council) published a full-page advertisement in the Okinawa Times proclaiming, 'Okinawa belongs to Okinawa, we are in no hurry to return to Japan.'[53] Some Anti-Reversionists argued that 'Okinawans had not capitalized on their cultural uniqueness, nor used their position for bargaining over the bases and other issues.'[54] In 1970, Arakawa Akira published his famous piece entitled 'Han fukki ron' (Anti-Reversion Theory) in which he criticised the very construct of the 'nation-state.'[55] Arakawa argued that Okinawa would never find liberation under a system based on historical narratives of assimilation that stemmed as far back as the 1600s.

-

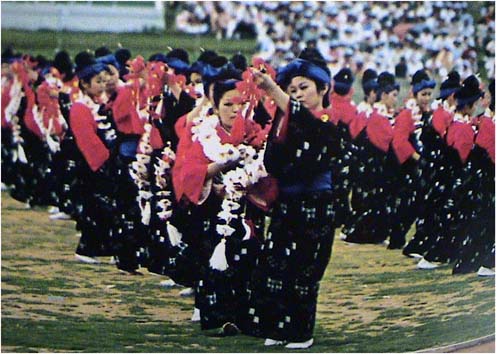

Despite Anti-Reversion sentiments, Okinawa officially returned to Japan in May 1972, and the Japanese government worked quickly to reclaim Okinawan culture under the larger umbrella of Japanese traditions. Corresponding with Reversion in 1972, the Japanese government selected several cultural treasures from Okinawa, including the classical dance drama form of kumi odori, to be designated as Nationally Important Intangible Cultural Property. Barbara Thornbury explains that from Japan's perspective the timing of these designations may be understood in this way: 'we were waiting for these cultural treasures to come back to us and are immediately conferring upon them the highest status we have.'[56] Okinawan performing arts were also appropriated as part of the Wakanatsu Kokutai (Special National Athletic Meet) to be held across Okinawa in May 1973. Celebrating one year from Reversion, the Wakanatsu games served as a symbolic spectacle of re-embracing Okinawa into the Japanese national fold. At the opening ceremony, thousands of Okinawan dancers of all ages performed, embodying the opening day message: 'The people of Okinawa Prefecture, upon reverting back to the fatherland, vow to contribute to Japanese culture through our own cultural characteristics.'[57]

Figure 11. Opening ceremony of the Wakanatsu Kokutai 1973. Source: Wakanatsu Kokutai, Naha: Okinawa-ken Tokubetsu Kokutai Jimusho, 1973, p. 4.

Figure 11. Opening ceremony of the Wakanatsu Kokutai 1973. Source: Wakanatsu Kokutai, Naha: Okinawa-ken Tokubetsu Kokutai Jimusho, 1973, p. 4.

|

Dancing through Okinawa in flux

-

During the complex era of Reversion and anti-Reversion movements, Kodama started grappling with the historical significations and political consequences of what it meant to return to Japan. In 1967, she began work on her next historical dance theatre, Ruten Okinawa: Okinawa 1300 nenyo no Monogatari (Okinawa in Flux: A Story of Okinawa over 1300 Years). She conducted extensive research on what she termed 'the hardships and struggles' of Okinawa's complicated past.[58] With the Preservation Society performers, Kodama debuted this piece in Tokyo at the Tōyoko Theatre in Shibuya on 26 May 1972, only eleven days after Okinawa officially reverted back to Japanese sovereignty.

-

The group re-staged this drama in Okinawa on 17 February 1973 at the Naha Citizen's Meeting Hall. The performance event, dedicated to the memory of Tokashiki Shūryō, commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Tokyo Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society. It was sponsored and promoted by Okinawa Prefecture, Naha City, NHK Okinawa Broadcasting Company, the Ryukyu Shimpō newspaper, and Okinawa TV. Promotional materials billed the event as a timely performance set in a complex historical moment:

Even as many problems remain in Okinawa, still the new life of 'Okinawa Prefecture' has started. And within the past nine months, Japan-China relations have been restored, and it seems like peace may finally start to arrive in war-engulfed Vietnam…Precisely at this moment when the connection between mainland Japan and Okinawa has been returned, we must highlight this return by investigating Okinawa's history with the performance of Ruten Okinawa in Okinawa.[59]

With the endorsement of the Prefectural Government and Governor Yara Chobyo, the 1973 performance of Ruten Okinawa may be read as situated within standard discourses of the early post-Reversion era. Official narratives on the past erased a history of colonial violence and political betrayal by celebrating Okinawan ethnic identity and unique performance traditions as a part of Japan's broader culture and history. Set within this immediate backdrop, Kodama's Ruten Okinawa not only echoes these narratives of the early post-Reversion era but also presents a distinctly more complicated view of Okinawan cultural history, identity, and traumatic loss. Kodama traces collective memories and experiences of trauma from early modern military invasions and colonial domination to the Battle of Okinawa and ongoing struggles with militarism in the postwar era.

-

The dance drama is organised into two acts: Act I comprised of four scenes and Act II with six scenes. The action opens with a 'Prologue' set in wartime Okinawa, described in this article's introduction. At the end of the battle scene, Kodama Kiyoko first appears as the incarnation of the feminine shima no seishin (spirit of the island). In direct contrast to the horrors of war, the spirit is the dancing embodiment of 'Okinawa's peace-loving heart.'[60] Following the Prologue, Act I Scene I flashes back to the seventh century when peaceful islanders are living in harmony with the sea, singing and dancing as they happily go about their daily work. Then all of a sudden the Sui dynasty of China attempts to force the islanders to accept Chinese rule. The spirit of the island conjures the powers of the Ryukyuan winds to defeat the Chinese. Kodama accomplishes this feat through a classical dance action of stomping her feet and pushing both hands forwards palms facing outwards.

-

Act II Scene I tells the story of the military invasion of the weaponless Ryukyu Kingdom by the Shimazu Clan of the Japanese Satsuma domain in 1609. This moment is clearly marked as the beginning of Okinawa's modern colonial history. The stage notes in the playbill read: 'in this way, forced under the despotic rule of Satsuma, Okinawa was colonized, suffered colonization.'[61] The following scene depicts the struggles of the Ryukyuans who were denied freedoms under Satsuma and tried to maintain a tributary relationship with the Ming Dynasty of China. However, by Act II Scene III, the Ryukyu Kingdom enters a second Golden Age in which the people cultivate their own unique culture. They carefully choreograph their dual subordination to Japan and China through dance diplomacy. Act II Scene IV depicts the Meiji military guards arriving in the Ryukyus to occupy Shuri Castle and forcibly make 'Ryukyuans' into 'subordinate people of Japan.'[62] The scene shows the Disposition of the Ryukyus, which sought to eradicate Ryukyu remnants to create Okinawa Prefecture. In the following scene, the Ryukyu King is exiled to Tokyo, the Ryukyu court is dismantled, and the spirit of the island dances at the sadness of the loss of Ryukyuan culture. The narrator explains that local traditions continue on in secret, hidden from the colonial administration in Okinawa. The final scene returns to the Battle of Okinawa, June 1945. The stage commentary explains that on this southern island where the sun shines and island people live happily, the harsh sounds of military planes and bombs are heard across the sky. The spirit of the island expresses the sufferings of the people and their desires for peace.

-

Throughout Ruten, Kodama accomplishes more than simply revisiting traumatic historical moments. Rather, she employs specific dance actions and performance traditions to help Okinawan audiences 'work through' collective memories of suffering. Although most of the dancing derives from formal stage versions of dances, Kodama also borrows from local festivals and religious practices threatened by the aftermath of WWII but recuperated by her research tour in the 1950s. She incorporates elements from the tradition of chondara ('persons from the capital'), the origins of Okinawan ancestral celebrations of eisā (drum dance). The Okinawan concept of chondara may be analogous with mainland Japanese kadozuke and nenbutsusha, itinerant performers who spread Buddhist sutras traveling door to door.[63]

-

Chondara represents a reclaimed traditional mode of healing that involves the arrival of sacred forces from a world beyond into the human realm. During the Prologue, before she appears on stage in the spotlight, Kodama recites a chondara chant. By invoking the chondara and embodying the island spirit, Kodama transports the audience, not only back in time, but also to another world, a world where the boundary between human beings and spirits remains blurred. She produces the spirit of the island as a feminine spirit who protects the people by performing a traditional Ryukyu women's court dance entitled yanagi (willow). Incorporating all of the dance actions that index feminine movements such as suriashi (sliding feet) and konerite (kneading hands), yanagi functions as a dance-ritual performed to ward off 'evil spirits,' often performed for the 'opening of new buildings or tombs in Okinawa.'[64] The dancer uses three to four flower accoutrements, including a basket of flowers, a willow branch, a plum branch, and a peony branch to cleanse a given space. For the Prologue of Ruten, Kodama selected a deigo branch instead of a willow or plum branch. This Okinawan species of an Indian coral bean plant blooms between March and May and has been associated with collective memories of the beginning of the Battle of Okinawa (1 April 1945).[65] It was also chosen as Okinawa's Prefectural Flower at the time of Reversion. Kodama's juxtaposition of the yanagi dance after the opening images of WWII battle scenes signifies a cleansing of the theatrical space for the audience to experience collective healing. She accomplishes this cleansing through specific dance actions, such as offering the deigo branch to the heavens and bowing to appease the gods.

Figure 12. Kodama Kiyoko performing the willow dance; she bows in reverence and prayer to the heavens. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figure 12. Kodama Kiyoko performing the willow dance; she bows in reverence and prayer to the heavens. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

-

Along with chondara, eisā and court dances, Kodama's embodiment of the female gendered island spirit indexes another standard religious folk practice known as mabui-gumi, often translated as 'spirit stuffing.' Mabui or spirit represents the essence of the individual self. When training younger generations of dancers, Kodama explains that the real meaning of Okinawan dance comes from mabui, from the place of the spirit, and thus all performances, even on stage, should be viewed as imbued with this spiritual presence.[66] When an individual is believed to have suffered spirit loss due to a traumatic or horrifying experience, a ritual of restoring the spirit to the body may be performed. In addition to specific ritual actions conducted by a shaman for serious cases, mothers or other matriarchal figures in a family may perform smaller rituals at the place where the loss of spirit occurred.[67]

-

In recent years cultural critics and artists such as Medoruma Shun have employed the concept of mabui-gumi in popular representations of traditional Okinawan practices. Medoruma received the Kawabata Yasunari prize for his short story entitled, Mabui-gumi (1998). In the story, the main character experiences a form of spirit loss that forces him to grapple with haunting images of the war and contemporary struggles with Okinawa's commercialised identity. Similarly, in the film Mabui (1999), Matsumoto Yasuo utilises spirit loss as an extended metaphor to describe postwar shock in Okinawa. One scene vividly illustrates the gendered ritual of spirit stuffing when a little boy falls down and scrapes his knee. His mother quickly brings him back to the place where he fell, touches the ground and then the boy's chest, while chanting 'mabu-ya, mabu-ya,' calling the spirit back into his body.

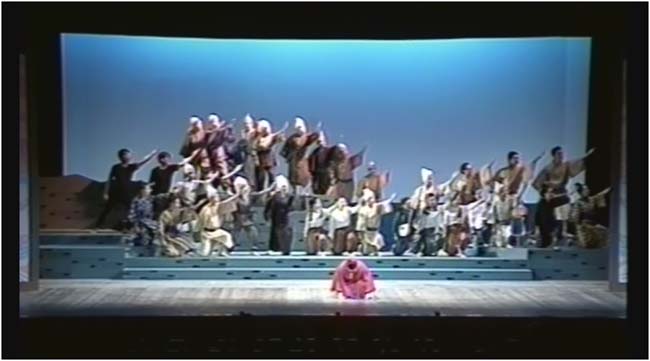

-

More than thirty years before these popular depictions of spirit stuffing, Kodama invoked the mabui-gumi ritual on stage by dancing to pacify the souls of the dead and to return the mabui spirit back to the hearts of Okinawans. She performs this ritual by returning to the exact historical moment, re-configuring the action, and then 'dancing through' trauma so the lost soul may be properly returned. In the final scene of Ruten immediately following images from the Battle of Okinawa, bodies of dead Okinawans lie strewn across the stage. The dancers wear costumes representing different groups of people who were all affected by the war, including young female characters wearing the Himeyuri uniform. Kodama enters the stage, draped in a garment of bright red, representing Okinawa's rivers and seas 'turned red from blood.'[68]

Figure 13. Final scene of Ruten Okinawa, Okinawan bodies strewn across the stage. The spirit of the island is dressed in red, representing the color of the sea tainted with blood. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figure 13. Final scene of Ruten Okinawa, Okinawan bodies strewn across the stage. The spirit of the island is dressed in red, representing the color of the sea tainted with blood. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

She performs a classical hand movement known as kirikaeshi, in which her right hand is brought in towards the mizōchi (centre of the chest) roughly indicating the area of the chimu (Okinawan dialect for heart or spirit). Twisting her hand in a kneading fashion to push away from her body, Kodama then performs a left turn to face upstage, her back towards the audience, with bodies lying all around her.

Figures 14–16. Final scene, Kodama performs dance actions to prepare the lost souls of Okinawa to rise again. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figures 14–16. Final scene, Kodama performs dance actions to prepare the lost souls of Okinawa to rise again. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

As she returns to face the audience, the bodies rise, thus signifying a return of the bodies' spirits.

Figures 17–18. The dead souls have their spirits returned, they are summoned into the world of the living through the dance-ritual actions of the spirit of the island. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figures 17–18. The dead souls have their spirits returned, they are summoned into the world of the living through the dance-ritual actions of the spirit of the island. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

Analogous to Jennifer Ewing Pierce's description of what Cape Breton dancing accomplishes, Kodama creates a 'seemingly mystic action' in which 'the individual body collapses into the social body, the future collapses into the past, and the dead truly rise again.'[69]

-

When the spirits gather behind Kodama as she continues to dance, the silhouette of a fighter plane appears above them. Consequently, the spirits become enclosed behind the shadowy projection of a US military base fence.

Figures 19 and 20. The lost souls have returned after the trauma of WWII and the Battle of Okinawa only to find themselves trapped behind a US military base fence with an American fighter plane above them. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figures 19 and 20. The lost souls have returned after the trauma of WWII and the Battle of Okinawa only to find themselves trapped behind a US military base fence with an American fighter plane above them. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

-

Kodama describes this last image as both a depiction of Okinawa in June 1945 and a reflection of the state of Okinawa at the time of Reversion. She notes:

In this place, on the ground at dawn, there are the dead bodies of our many island people who were sent to heaven. But the heart of the island people who hope for peace continues to live strongly. As the spirit of the island restores the heart of the island people, many people ask themselves, has Okinawa really returned?[70]

Paired with the opening sequence, Kodama stages the final scene to critique the realities of Reversion, in which US military bases remained on the island and B52s headed for Vietnam continue to penetrate the landscape of Okinawa. Through her performance, Kodama depicts Okinawa's return to Japan in 1972 as yet another historical example of collective trauma in Okinawa. The title 'Okinawa in Flux,' alternatively translated 'Changing Okinawa,' highlights the irony that in terms of Okinawa's subjugated position little has changed fundamentally over thirteen hundred years. In this sense, Kodama poses a biting political question as to whether Reversion is merely the newest manifestation of Okinawan centuries-old oppression. The re-embodiment of historical tragedies in Kodama's performance creates new, empowering possibilities to transcend victimisation narratives by confronting a complex past. Kodama's final scene provides a form of pacifying, cleansing and healing Okinawan souls, rather than accepting a sense of hopelessness or longing for an erasure of history.

Figure 21. The Okinawan people look forward to a future of possibility and change, guided by the spirit of the island who has cleansed them and offered new ways of living with the past. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

Figure 21. The Okinawan people look forward to a future of possibility and change, guided by the spirit of the island who has cleansed them and offered new ways of living with the past. Source: Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992.

|

Conclusion

-

Even as post-imperial discourses of 1970s Japan employ performance to gloss over narratives of colonial violence and political betrayal, Okinawa's playwright and performer Kodama Kiyoko suggests that Okinawans do not dance to forget, but rather to cope and to work through remembering. With the embodied act of dancing, Kodama rewrites historical narratives to redefine new ways of dealing with tragedy, trauma and loss in Okinawa within the broader context of post-imperial Japan. She re-appropriates gendered performance traditions to transcend victimising narratives by resurrecting traditional images of Okinawan women, who were once valued for their spiritual powers and alternative ways of knowing. Particularly in her 1973 performance of Ruten Okinawa, Kodama suggests that to heal themselves after the trauma of WWII and the ongoing postwar militarism, Okinawans must reclaim their feminine island spirit to rethink ways of articulating identities and defining local subjectivities.

-

In an afterword for the 1992 restaging of Ruten Okinawa, Kodama explains:

It has been 20 years since reverting back to the mainland, but I am still appealing to the shima no seishin (spirit of the island) with our long cherished wish of moving towards peace with no military bases, hoping that chances for a beautiful life will never cease to develop, and that the blue sea will never again change to a red sea.[71]

As Okinawa faces the lingering effects of colonial modernity and the legacies of imperialism, Kodama's work represents an example of how activist performers reconfigure the historical trauma of the past as a means to embodying change for the future.[72] Despite the realities of post-imperial Japan, which threaten to re-play and repeat colonial oppression, Okinawans may reclaim historical agency and 'dance through' trauma to create their own histories.

-

The example of Kodama and her career of activist performance also raises critical questions about scholarly approaches to and historiography on trauma. As Dominick LaCapra attests, working through trauma is not simply achieved by narrative alone, in fact often times narrative approaches remain too limiting and risk an 'acting out' of the past. Saunders and Aghaie cite Wedeven Segall and his comparative study of collective performances in Iraq and South Africa to explain how 'embodied performance provides opportunities to deal constructively with traumatic memories of torture, abuse, mass murder, social and cultural dislocation and even genocide.'[73] Rather than narrative retellings, traumatised resistance fighters 'found ways to use cultural performances such as drama and song to overcome grief, alienation, and victimization.'[74]

-

Likewise, Kodama offers Okinawan audiences a chance to transform their individual pains into a communal form of coming-to-terms with collective trauma. In the end, a critical examination of Kodama's performance encourages scholars to move beyond standard understandings of the colonial archive as the defender of history. For meaningful studies of trauma, scholars must also consider how individual dancers, their personal historical narratives, and their multi-modal performances offer alternative embodied archives.

Endnotes

[1] I am grateful to the reviewers, editors, and copy editor for all of their insightful suggestions for this article. In particular, the comments on how to strengthen the connection between performance, trauma studies, and historiography were especially useful. The research for this article was funded in part by a Blakemore Foundation Grant (2001–2002) to Yokohama, Japan and a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship (2005–2006) at the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa, Japan.

[2] The still shots included in this article are all from the VHS version of Ruten Okinawa, copyrighted 1992. Kodama Kiyoko provided the author with this video to use only for research purposes, the rights belong to the archives of the Tokyo Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society.

[3] The term shima no seishin is what Kodama envisions she is making manifest on stage, she is the embodiment of the island spirit. The term suggests a sort of double entendre referring to both the personification of the Okinawan people's spirit and the personification of the physical island of Okinawa. The term also builds off images of Okinawans as 'shimanchu' or 'island people.'

[4] The Japanese name of the preservation society is Tōkyō Okinawa Geinō Hōzonkai. Although the US Military Occupation officially ended, this political change did not alter the fact that roughly one third of lands in Okinawa continued to remain as US military bases. In addition, Japan relocated Self-Defense Forces onto the islands shortly after Reversion. Many Okinawan activists protested against these issues that maintained an overwhelming military presence in Okinawa. On the general sense of disenchantment and disappointed experienced by peace activists in the post-Reversion era, see especially Miyume Tanji, Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa, London: Routledge, 2006.

[5] I encountered Kodama and her work in 2001–2002 when I had the unique opportunity to attend classes at the dance research studio of the Preservation Society in Yokohama, Japan. In addition to studying dance, I was able to interact with Kodama personally in her home and gain limited access to the archives of the Preservation Society. I conducted several interviews with her and her nieces, who are now heirs to her dance lineage and the Preservation Society. For my analysis of the dancing, I draw from my experiences of learning dances with Kodama and at the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa, but also from a unique opportunity to record Kodama providing details and commentary on a video of the Ruten Okinawa performance.

[6] Tokashiki was part of the first generation of new actors to perform in the censored and commercialised theatres of the licensed pleasure quarters created by Meiji policies forbidding Ryukyuan dances. For more on his life and professional experiences, see Tokashiki Shuryō 'Aru haiyŪ no kiroku,' in Okinawa no geinō, ed. Haruo Misumi, Tokyo: Hōgaku to Buyō Shuppanbu, 1969, pp. 192–214 and Tokashiki Shuryō 'Jijoden,' in Nihon no Geidan: Buyō hōgaku, ed. Kikugorō Onoe, Tokyo: KyŪgei Shuppan, 1979, pp. 281–91.

[7] Ryūkyū Shimpō, 11 November 2005, http://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/storyid-8397-storytopic-6.html, accessed 8 June 2010. Kodama has also been selected as one of the first artists who will be featured in the 'Okinawan Oral History Film Archive,' held at the Institute for Ryukyuan and Okinawan Studies of Waseda University. See their website on the new database and journal, online: http://www.waseda.jp/prj-iros-waseda/. Following Kodama's passing in 2005, art historian and dance studies scholar Hateruma Nagako has begun an oral/performance history archiving project to organise, catalogue and preserve her works.

[8] Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2001. See also Rebecca Saunders and Kamran Aghaie, 'Introduction: mourning and memory,' in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, vol. 25, no. 1 (2005): 16–29, p. 17. Saunders and Aghaie criticise LaCapra for extending analysis of individual clinical cases of trauma to collective trauma.

[9] Dominick LaCapra, History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004, p. 118.

[10] LaCapra, Writing History, p. 206.

[11] LaCapra, Writing History, p. 179.

[12] Saunders and Aghaie, 'Introduction,' p. 22.

[13] Saunders and Aghaie, 'Introduction,' p. 22.

[14] Saunders and Aghaie, 'Introduction,' p. 26.

[15] Robert Jay Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima, New York: Random House, 1967.

[16] Lifton, Death in Life, p. 405.

[17] Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Spaces, and the Dialectics of Memory, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 228.

[18] Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces, p. 11.

[19] Simon Featherstone, Postcolonial Cultures, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005, p. 71. Barbara Browning, Samba: Resistance in Motion, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 5.

[20] Steve Rabson, 'Meiji assimilation policy in Okinawa: promotion, resistance, and "reconstruction",' in New

Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan, ed. Helen Hardacre and A. L. Kern, New York: Brill, 1997, pp. 635–55, p. 643.

[21] An Okinawan girl would receive tattoos as part of rites of passage at key moments in her life, when she gets married, has children, becomes a widow, etc. The Meiji Japan government issued a Prohibition on Tattoos in 1890. Mainland Japanese author Nakamoto Masayo cites this law and the problems associated with female tattoos in his didactic text on how Okinawan women should be educated to be proper imperial subjects unified with the cultural practices of Japan. Nakamoto Masayo, Okinawa jokan, Naha: Ryūkyū Shinpōsha, 1902, p. 47. For a discussion of women's clothing in the first Girls' Training School in Okinawa, see Hokama Yoneko, Jidai o irodotta onnatachi: Kindai Okinawa joseishi, Naha: Niraisha, 1996, p. 47.

[22] The character mō refers to the fields, but also to hair, suggesting a reference to bodily hair, which may be read as signifying a sexual connotation. Iha Fuyū explains how this practice developed historically as a meaningful community-building social interaction. Iha Fuyū, 'Ma-gaya yori mo-ashibi made,' in Minzoku gaku vol. 2, no. 1 (1930): 46–51.

[23] Although many communities in Japan, including parts of Okinawa, switched to the Gregorian calendar during the Meiji era, some areas still use a lunar calendar to decide when to hold ritual celebrations. According to Fanny Mayer's discussion of the calendar of village festivals in Japan, many parts of Japan celebrate obon between 15 and 17 July. However, she notes that 'in the country', the date may fall a month later, closer to 15 August as a compromise between the Gregorian calendar, the lunar calendar, and natural calendars of agriculture. See Fanny Hagin Mayer, 'The calendar of village festivals: Japan,' in Asian Folklore Studies vol. 48, no. 1 (1989): 141–47, p. 145.

[24] This article features Kodama telling her story in her own words, but prefaced by Sakai Usaku. See Sakai Usaku, 'Watashi ga atta saigo no chondara: Kodama Kiyoko,' in Nantō Kenkyū vol. 35, (1994): 9–17, pp.13–14.

[25] In the creation of Okinawa Prefecture, all things Ryukyuan were targeted as either backward or as suggesting a continued loyalty to China. Dance magistrates who held positions of nobility lost their status with these changes. Tokashiki explains what it was like for his teachers, the last of the dance magistrates, during this time. Tokashiki 'Aru haiyū no kiroku', pp. 194–96. On the decree controlling performances, see also Yano Teruo, Okinawa buyō no rekishi, Tokyo: Tsukiji Shokan, 1988, p. 179.

[26] John Lie discusses how Okinawa becomes a classical colonial economy, forcing many to emigrate. John Lie, Multiethnic Japan, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 98.

[27] During my interviews with activist scholar Arasaki Moriteru, he remembered that his father also changed his name to Nīzaki when they first moved to mainland Japan. At the insistence of his mother, they then changed it back when he was still in elementary school. Interview with Arasaki Moriteru, Haebaru, July 2006. For more on the topic of names and a list of how Okinawan names changed to Japanese names, see Kinjō Seitoku, Okinawa-ken no hyakunen, Tokyo: Yamakawa Shuppansha, 2005, p. 178.

[28] Truk's history overlaps in some ways with Okinawa, a small island country colonised by Japan and then re-colonised by the US. In the present-day, Chuukese are legally US citizens. On prewar Truk history, see Susan Dolan, Truk: The Lagoon Area in the Japan Years, 1914-1945, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1974.

[29] Tomiyama Ichirō, 'Colonialism and the sciences of the tropical zone: the academic analysis of difference in ?the island peoples",' in Formations of Colonial Modernity in East Asia, ed. Tani Barlow, Durham: Duke University Press, 1997, pp. 199–221, p. 213.

[30] For more on colonial policies towards Okinawans in the South Seas, see the works of Yanaihara Tadao, especially Yanaihara Tadao, 'Nanpō rōdō seisaku no kichō', in Shakai seisakatsu jihō vol. 260 (1942): 156–57. The comment on music and dancing by mainlander Gondō Seikyo is cited in Mark Peattie Nan`yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885–1945, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988, p. 221. In the case of Palau, Okinawans were not allowed to emigrate after 1942 and even before then they were forbidden to bring their sanshin (three stringed musical instrument), a symbol of their backwardness and non-Japanese identity; see Tomiyama Ichirō, Bōryoku no yokan: Iha Fuyū ni okeru kiki no mondai, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002, pp. 66–67.

[31] Miyagi Harumi, 'Fūzoku kairyō no haikei,' in Naha onna no Ashiato: Naha joseishi (kindai hen), Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan, 1998, p. 361.

[32] Hateruma, 'Buyōka ōraru hisutorī,' p. 64.

[33] Several sources discuss the issue of how Okinawans served in and for the Japanese military in WWII. On the conscription of young men to the military corps, including his own participation in the Battle of Okinawa, see Ota Masahide, Okinawa no kokoro: Okinawa sen to watakushi, Tokyo: Iwanami Shinsho, 1972. For a discussion of how Okinawan women were recruited to serve in Japan's system of institutionalised sexual slavery, see Takazato Suzuyo, Okinawa no onnatachi: josei no jinken to kichi, guntai, Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 1996.

[34] As more research is done, the number of casualties is represented differently and continues to grow: see Ishihara Masaie, Oshiro Masayasu, Hosaka Hiroshi, and Matsunaga Katsutoshi, Soten: Okinawasen no Kioku, Tokyo: Shakai Hyoronsha, 2002.

[35] Matthew Allen, Identity and Resistance in Okinawa, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

[36] The term 'sacrificed' represents the terminology used by many activists and the Himeyuri survivors themselves to talk about how they were abandoned by the Japanese troops they had been honorably serving. On the testimonies and historical significations of the Himeyuri, see especially Linda Isako Angst, In a Dark Time: Memory, Community, and Gendered Nationalism in Postwar Okinawa, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008.

[37] This topic is still being researched by women's groups in Okinawa, namely the Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence and the Pyonfakai Heiwa (Peace) Association. See Takazato Suzuyo, Okinawa no onnatachi: josei no jinken to kichi, guntai, Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 1996.

[38] For first hand accounts by women who experienced the war, see Okinawa-sen, haha no inori: musume ga tsuzuru hahaoya no kiroku, Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha, 1977.

[39] Although I had heard about yaka bushi (refugee songs), I learned more about these songs through conversations with Taira Osamu, Ginoza Eiko, and other peace activists at the Henoko sit-in tent, 2005–2006. To promote the Henoko movement to prevent the construction of a new military base off the coast of Henoko Beach and Oura Bay, the Inochi wo Mamorukai made t-shirts with a yaka bushi song written on the back. The song describes how everything was burnt in the war, the mountains, fields, and food, and it was the sea that provided Okinawans with the ability to sustain life. This political message drawing on collective trauma of the past helps to promote a reading of present-day Okinawan identity based on the image of uminchu, an Okinawan term for people who live in a symbiotic relationship with the sea.

[40] Yano, Okinawa buyō no rekishi, p. 213.

[41] This quote is from Ruth Ann Keyso, Women of Okinawa: Nine Voices from a Garrison Island. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 41. Nakamaru writes about her experiences in the immediate postwar in her memoir, Nakamura Fumiko, Watashi no naka no Taishō Shōwa, Naha: Nakamura Bunshi, 1990. She also discusses her personal transition of working as a teacher under the militarised school system in wartime Okinawa to becoming a postwar peace educator.

[42] Interview with Matayoshi Shizue, in Okinawa at her office in the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts, August 2006.

[43] The Uruma Shimpō newspaper started in August 1945. Written by Okinawans, but supported and censored by the US military, it includes some references to these performances. See especially 4 April 1946 in Uruma Shinpō vol. 1–2, 1945–1946, Tokyo: Fuji Shuppan, 1999, p. 76.

[44] Wauke Tomiko, 'Watashi mo kokoro ni nokoru,' in Shomin ga tsuzuru Okinawa sengo seikatsushi, Naha: Okinawa Taimususha, 1998, p. 161.

[45] Gushiken Kosei, 'Futatabi ajiwaenu ?ittaikan",' in Shomin ga tsuzuru Okinawa sengo seikatsushi, Naha: Okinawa Taimususha, 1998, pp. 160–61.

[46] Interview with Kodama Kiyoko, Yokohama, Japan, at Kodama Kiyoko's private residence, attached to the Tokyo Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society dance space, May 2002.

[47] Kodama Kiyoko, 'Okinawa geinō hozonkai shuisho (1948),' in Kodama Kiyoko Geinō Kōen, Gushikawa City: Gushikawa Kyōiku Iinkai, 2001, pp. 188–89, p. 188.

[48] Although she did not receive financial support from the US administration in Okinawa, Kodama found that the occupying officials were supportive of her efforts to reclaim dances. At a time when some Okinawans stuck in mainland Japan were not allowed to return, Kodama was given permission to return to the islands for her research. She was also allowed to borrow a movie theatre in order to record some of the lost chondara chants on audiotape for cultural preservation.

[49] Arasaki has written extensively about peace activism in Okinawa, his own political protest, and his own struggles with identity consciousness. See for example, Arasaki Moriteru, Heiwa to jiritsu o mezashite: Okinawa no tenki wa Nihon no tenki, Tokyo: Gaifusha, 1997. The way he described this particular inability to perform the embodied action of banzai comes from a personal interview at his home. Interview, with Arasaki Moriteru, Okinawa, July 2006.

[50] While scholars may mention that a cultural framework was employed in the rhetoric of Reversionists, most sources in English and Japanese privilege the 'political' aspects of the Reversion movement over the specific use of cultural expressions such as dancing, music, or theatre. See for example Gordon Warner, The Okinawan Reversion Story: War, Peace, Occupation, Reversion, 1945-1972, Naha: Executive Link, 1995. In Japanese see Ohama Nobumoto, Okinawa fukki he no michi, Tokyo: Hara Shobo, 1968.

[51] Yano, Okinawa buyō no rekishi, pp. 215–16.

[52] Honda Yasuji and Soetsu Yanagi, 'Okinawa Geinō,' in Asahi gurafu vol. 12, no. 23 (1953): 12–17, p. 13.

[53] Okinawa Taimusu, 1 October 1969.

[54] Nakachi Kiyoshi, Ryukyu-US-Japan Relations: The Reversion Movement, Political, Economic, and Strategical Issues, Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University, 1989, p. 132.

[55] Arakawa Akira, 'Han fukki ron,' in Shin Okinawa Bungaku vol. 18 (1970): pp. 50–72.

[56] Barbara Thornbury, 'National Treasure/National Theatre: the interesting case of Okinawa's Kumi Odori Musical Dance-Drama,' in Asian Theatre Journal vol. 16, no. 2 (1999): 230–47, p. 234.

[57] Wakanatsu Kokutai, Naha: Okinawa-ken Tokubetsu Kokutai Jimusho, 1973, p. 15.

[58] Some of her broader comments about the piece and what she is trying to accomplish come from the 1973 playbill. Kodama Kiyoko, 'Okinawa ni omou (1973),' in Kodama Kiyoko geinō kōen, Gushikawa City: Gushikawa Kyōiku Iinkai, 2001, p. 93.

[59] This quote comes from the promotional materials about the event. It was reprinted in the front of the playbill from 1973, Kodama, Kodama Kiyoko geinō kōen, p. 84.

[60] Kodama, Kodama Kiyoko, p. 94.

[61] Kodama, Kodama Kiyoko, p. 95.

[62] Kodama, Kodama Kiyoko, p. 96.

[63] Jane Marie Law, Puppets of Nostalgia: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of the Japanese Awaji Ningyō Tradition, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997, pp. 33–34.

[64] Kinjo Mitsuko, Ryūkyū buyō no sekai: kokoro to katachi, Naha: Ryūukyū Geinō , 1991, p. 116.

[65] During my interviews and participant observations with peace activist Ginoza Eiko, she told me about her mother's war memories and the collective memory of Okinawans more generally who remember that the war began when the deigo plants were in bloom. Their bright red flowers seem to echo the fire, explosions, and destructions of the war.

[66] Interview with Kodama Kiyoko, Yokohama, Japan, at Kodama Kiyoko's private residence, attached to the Tokyo Okinawa Performing Arts Preservation Society dance space, March 2002.

[67] This description of mabui-gumi I received from talking with ensemble members of the Preservation Society, who brought me Honda Yasuji's book on folk performance to help me understand more about the connections between dancing, religion, and ritual. Honda Yasuji, Minzoku geinō: kyōdo ni ikiru dentō, Tokyo: Shakai Shisō Kenkyūkai Shuppanbu, 1962. On folk beliefs and religious practices in Okinawa, see also Masaharu Matayoshi and Joyce Trafton, Ancestors Worship: Okinawa's Indigenous Belief System, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Inc., 2000.

[68] Kodama, 'Okinawa ni omou,' p. 93.

[69] Jennifer Ewing Pierce, 'Toward a poetics of transubstantiation: the performance of Cape Breton music and dance,' in The Drama Review, vol. 52, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 44–60, p. 55.

[70] 1973 plot outline in the playbill. Kodama, Kodama Kiyoko geinō kōen, p. 96.

[71] From the playbill of her 1992 performance, where Governor Ota Masahide also comments on the historical and political significance of Kodama's work. Kodama Kiyoko, 'Atogaki (1992),' in Kodama Kiyoko Geinō Kōen, Gushikawa City: Gushikawa Kyōiku Iinkai, 2001, p. 164.

[72] Beginning in the 1990s, historical performances that reclaim dance traditions as part of larger political protests become much more common. See my preliminary discussion of this topic: Valerie Barske, 'Nuchibana: Okinawans dancing for peace,' in Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movements vol. 12, no. 3 (2003): 145 – 66. In future works, I plan to discuss the most recent performative re-embodiment of a tragic moment in postwar Okinawan history. Peace activist Ginoza Eiko helped students in Okinawa stage a performance to commemorate the half century anniversary of the US jet crash into Miyamori Elementary School on June 30, 1959. The Half Century Miyamori group just released a DVD version of the performance, which Ginoza is currently working to have subtitled in English. See Half Century Miyamori, 'Fukugi no shizuku: Wasuretaikedo wasuretakunai, wasurete ha ikenai,' Miyamori Elementary School, 2009.

[73] Rebecca Saunders and Kamran Aghaie, 'Introduction: mourning and memory,' in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East vol. 25, no. 1 (2005): 16–29, p. 20.

[74] Saunders and Aghaie, 'Introduction,' pp. 20–21.

|