Constructing the 'Modern Couple'

in Occupied Japan

Mark McLelland

Introduction

-

The immediate post-war years in Japan are frequently referred to as the yakeato jidai or 'burned-out ruins period.' Photographs from this time show a panorama of skeletal buildings amidst piles of rubble. Ragamuffin children, many of them orphans, play barefoot while adults scavenge among the ruins for anything that might be bartered or put to use: tools, clothing, pots, and most importantly, food. An enormous number of city dwellers had lost everything in the war. Indeed, as historian Igarashi Yoshikuni points out, for many survivors, their bodies were the only things that they had managed to preserve from the air raids.[1] With the collapse of the militarist regime there was a widespread rejection of the 'spiritual' wartime ideology that had been used to justify privation and self sacrifice. Instead, the needs of the body or the 'flesh' (nikutai) played much on people's minds, giving rise to a popular literary genre, 'literature of the flesh' (nikutai bungaku), that graphically depicted the physical needs of embodied existence.[2]

-

Despite the horrors of war that were burned on people's memories and the extreme deprivation that characterised the immediate post-war months, extraordinary scenes of bodily exuberance are recorded as taking place soon after Japan's defeat. The imperialist regime had insisted upon 'the standardization and disciplinization of body movements and human behavior'[3] but the end of the war was celebrated by some workers who staged 'wild parties' where women wore lipstick and couples danced to jazz music—activities that had previously been banned as decadent, Western inventions.[4] Although the search for food was the main priority on most people's minds, as Igarashi notes, the burned-out ruins provided an incongruous setting for the celebration of the 'raw, erotic energy of Japanese bodies.'[5] A sense of this libidinous excess can be gleaned from a reading of the popular press of the period which breathlessly proclaimed the overthrow of 'dreary feudal customs' and the ushering in of a new period of 'sexual liberation' (sei kaihō) and 'free love' (jiyū ren'ai).[6]

-

In this paper I offer an initial examination of discourse about heterosexuality apparent in a popular 'pulp' genre known as kasutori ('the dregs') newspapers and magazines that burst on the scene barely six months after Japan's surrender in August 1945, and which continued to proliferate until the end of the decade.[7] I consider the manner in which female bodies were represented and discussed in relation to new trends encouraging the liberalisation and democratisation of attitudes toward male-female relationships and female sexuality. In particular, the public display or performance of heterosexual coupledom became an important indicator of individuals' support for 'modern,' 'democratic' ideals.

Early post-war social and cultural reforms

-

A number of Allied initiatives supported a rapid change in the cultural scenarios that gave symbolic meaning to women's status. While the impact of Occupation reforms upon women's social and economic status has been extensively critiqued,[8] less attention has been paid to the psychological and cultural impact of the dismantling of the patriarchal household system, particularly regarding women's new ability to engage in what the popular press termed 'the romantic-love marriage system' and 'free love.'[9] The Occupation authorities were keen to 'liberate' Japanese women from what they considered 'feudal' customs, attitudes and practices.[10] Of course, as Susan Pharr points out, the Americans did not put forward a radical feminist agenda, rather 'they accepted the idea that woman's primary role in adult life is to be wife and mother, but believed that married women simultaneously could and should play other roles as well, such as citizen, worker, and participant in civic and social groups.'[11] Accordingly, under Allied supervision the Japanese constitution and criminal and family law were extensively rewritten so as to enfranchise women and dismantle the household system that had given family patriarchs considerable influence over women's lives, including choice of marriage partner.

-

Furthermore, Occupation authorities dismantled Japan's restrictive wartime censorship system which had the unintended effect of greatly increasing the freedom and range of public discussions about marriage, sex and eroticism.[12] The Occupation authorities also actively promoted a more 'democratic' vision of male-female relationships through the import and screening of Hollywood movies that supported the supremacy of romantic love.[13] These Hollywood 'love scenes' became important discussion topics in the popular press,[14] and were used as examples of how to conduct courtship. The sudden emergence and popularity of these 'kissing movies' led one columnist to argue that 'nothing, it seems to me, is exercising so potent an influence on the minds of young Japan as Hollywood,' identifying in particular, 'love-making.'[15]

-

The authorities also intervened in the scriptwriting processes of locally-made Japanese movies, requiring that young couples be shown making their own choice in marriage partner and that dating and even kissing be depicted.[16] As Joanne Izbicki points out, the 'new lustiness' in early post-war movies 'gained respectability as the basis for marriage and hence was linked to the new legal recognition of peoples' right to choose their own partners on the basis of inclination.'[17] In addition, magazine editorials, sometimes written by American women, and roundtable discussions among women about the advantages of the 'romantic-love marriage system,' were widely disseminated via both print[18] and radio.[19]

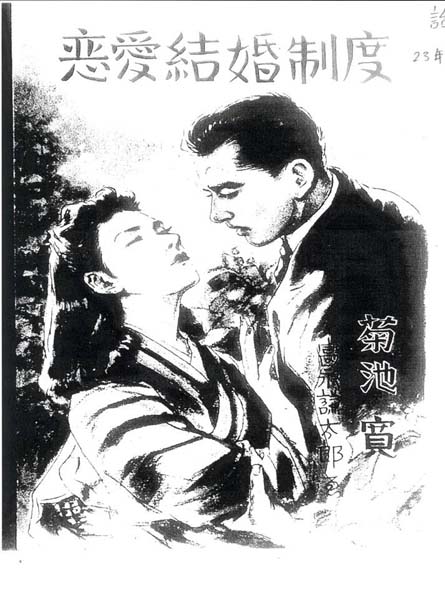

Figure 1. Front cover of the August 1948 edition of Hanashi dedicated to the 'Romantic Love Marriage System' and featuring an editorial by influential publisher, journalist and author, Kikuchi Kan.

Figure 1. Front cover of the August 1948 edition of Hanashi dedicated to the 'Romantic Love Marriage System' and featuring an editorial by influential publisher, journalist and author, Kikuchi Kan.

|

-

As important as these 'top-down' interventions were, also of significance was the very physical presence of American bodies on the streets of Japan's cities, especially those GIs who promenaded about town with their Japanese paramours. Cultural historian Tsurumi Shunsuke points out that 'for a man and a woman to walk abreast would have been considered immoral during the war,'[20] yet, within a few months of the arrival of Allied troops, it was a common sight to see American service personnel strolling hand in hand and canoodling in train stations and parks with the many women (known by the derogatory term 'pan pan') who exchanged sex and companionship for material and other rewards.[21] Furthermore, as Yamamoto Akira points out, in 1946 two hundred wives of senior US officers were moved over to Japan to aid their husbands who were working for the Occupation.[22] It became common to see officers in Tokyo strolling hand-in-hand with their wives and kissing them hello and goodbye. According to sexologist Takahashi Tetsu, the new authorities had to instruct the police that kissing was not an offence against public decency.[23] The visible presence of American bodies on the streets was particularly important since any discussion of Americans' romantic and sexual behaviour was severely censored in the popular press. Mention of 'fraternisation' between American service personnel and local women, in particular, was strictly policed by the Civil Censorship Detachment. Hence, first-hand observation of the 'unabashed love'[24] on display in public between GIs and their Japanese paramours was one of the most potent indicators that new cultural scripts were unfolding.

-

The popular press of the time is an important but so far underutilised resource for understanding the impact that these measures had upon lived experience. The kasutori press, in particular, described and encouraged a range of bodily performances that were variously coded as 'new,' 'modern,' 'anti-feudalistic,' 'democratic,' 'foreign' and 'American.' Male-female relationships were radically re-imagined in these publications and the 'new' or 'modern' couple became an important rhetorical device in arguments that claimed Japan had finally thrown off its feudal heritage. Over a three-year period many thousands of articles, editorials, opinion pieces and reports exhorted young men and women to reject feudal customs and enjoy each other's company more 'democratically.'[25] This literature was largely didactic in tone: it sought to instruct young people in modes of social intercourse that had been ideologically disavowed as 'decadent' and 'foreign' under the previous regime. Journalists, novelists, sexologists and a range of other social commentators, Japanese and non-Japanese alike, all sought to redefine the nature of male-female interaction, and attach new meanings to romance, sex, marriage and coupledom. Through explicitly linking 'sexual liberation' (sei kaihō) with the broader project of democratisation, the readers (and writers) of the kasutori press were able to think of themselves 'as liberated from the oppressive morality of the past' and to see the genre as playing a role in 'founding a new democratic society.'[26] This genre of writing, although largely overlooked because of its supposedly low-brow appeal,[27] is clearly important when considering the cultural impact of the US Occupation on Japanese attitudes to male-female relationships, sexuality and the body.

-

Although such alarmingly 'modern' trends as working women and love marriages had been discussed in Japan in the late 20s and early 30s as part of a popular cultural movement commonly referred to as ero-guro-nansensu (erotic, grotesque nonsense) as well as in more high-brow journalism,[28] from 1933 onwards Japan's descent into militarism severely curtailed the freedom with which such 'frivolous' topics could be discussed in the press. From 1939 the government control of paper supplies made it all but impossible to print material disapproved of by the authorities and 'even the word ?kiss" was banned.'[29] Sex, to the extent that it was discussed at all in the wartime press, was represented as a means of managing 'human resources' (ningen shigen) and not as a source of pleasure or relationship building.[30] Hence, the widespread discussion of sexual mores that re-emerged in the immediate post-war environment seemed startlingly new to many younger people and, for the first few years at least, was able to take place with little fear of censorship.[31]

-

To help make sense of this sudden outburst of talk about sex and romance, the notion of 'sexual scripting' developed by sociologists Simon and Gagnon can be usefully deployed. In the 1960s, William Simon and John Gagnon, influenced by emerging theories of social interactionism, developed a theory of sexual behaviour that stressed the importance of environmental and historical factors over purely physiological or personal elements. They argued that,

… there is no sexual wisdom that derives from the relatively constant physical body. It is the historical situation of the body that gives the body its sexual (as well as all other) meanings.[32]

Simon and Gagnon argued that sexuality was constructed with regard to 'cultural scenarios' that 'not only specify appropriate objects, aims and desirable qualities of self-other relations but also instruct in times, places, sequences of gesture and utterance.'[33] It is these 'qualities of instruction' that ensure that individuals are 'far more committed and rehearsed at the time of our initial sexual encounters than most if us realize.'[34] They posited that sexual behaviour was 'essentially symbolic' and that 'virtually all the cues that initiate sexual behaviour are embedded in the external environment.'[35]

-

Simon and Gagnon's argument is an early iteration of the 'social constructionist' approach to sexuality whose most famous proponent was Michel Foucault. Foucault argued that sexuality is not an inherent property of bodies, some kind of transcultural biological reality, but rather 'the set of effects produced in bodies, behaviors, and social relations by a certain deployment deriving from a complex political technology.'[36] This insight has important implications for globalisation studies since it helps us understand how seemingly 'personal' experiences such as sexual responsiveness are in fact highly structured in relation to the transnational movement of power, people, ideas and imaginaries. As Fran Martin reminds us, sexualities are not 'inert, autochthonous forces planted in the soil of a given location' but rather 'densely overwritten and hyper-dynamic texts caught in a continual process of transformation.'[37] To build on Martin's metaphor, Japan's Occupation period was characterised by a voluble sexual discourse in which previous attitudes toward sex and the body were quite literally being rewritten in line with new orthodoxies and ideas encouraged by the Occupation authorities and disseminated through media such as radio, film, literature and the press.

-

Japan's catastrophic defeat at the end of the Pacific War and its occupation by mainly US Allied forces from 1945 to 1952 ushered in a period of great social and cultural change in the realms of individual subjectivity and personal relationships as much as in the spheres of government, education and the economy. Simon and Gagnon note that such periods of dramatic social change 'have the capacity to call into question the very organization of the self'[38] and it is possible to understand the collapse of Japan's imperialist regime—and its supporting ideologies—at the end of the Pacific War as just such a moment, during which 'the very ecology of the self [was] disturbed.'[39] Simon and Gagnon go on to argue that such moments require that 'all aspects of the self that previously required a negotiated outcome must be reestablished.'[40]

-

The sudden collapse of Japan's imperialist regime and its attendant symbolic representations of appropriate gendered and sexual behaviour occurred alongside the suspension of the previous regime's censorship policies and the introduction of new and very visible representations of sex and gender supported by the Allied powers. Thus, it is not surprising that there should have been so much discussion in the early post-war press about the need to renegotiate and redefine male-female relationships.

-

However, it would be naïve to expect that this process of 'liberation' was without its drawbacks. Indeed, as Igarashi points out, one effect of the liberalisation of sexual mores is that it was no longer simply 'professional' women who were sexualised but women in general who were 'immediately caught up in market forces that offered them to male desire at a price.'[41] Despite a range of reforms aimed at increasing female agency at home and in the workplace, in the early post-war years women were still at a distinct disadvantage. Lower-class women with little social or cultural capital were particularly vulnerable to sexual predation by both Allied personnel and Japanese men alike.[42] Many hundreds of thousands of married women had lost their soldier husbands during the war and eligible bachelors were in short supply. It was estimated in 1952 that among men and women in the desirable age range (between 20 and 29 for women and between 24 and 34 for men), women outnumbered men seven to five. In Tokyo alone there were estimated to be 23,000 women looking for husbands.[43] Some women were forced into undesirable part-time associations with Japanese men who were already married. Known as 'Saturday wives' or 'business-trip wives,' they were understood to be modern-day concubines. Occupation officers, too, had their 'only-san,' women with whom they contracted relationships during their tour of duty, often to abandon at the train station upon their return home.[44] Despite the enthusiasm of the popular press, in this environment women were not always able to negotiate with their partners 'democratically.' However, a close reading of the post-war press does suggest that the much touted 'liberation' of sexuality and attendant efforts to re-imagine male-female relationships in a more 'democratic' fashion were more than rhetorical gestures.

The rise of post-war 'sex journalism'

-

In Japan, the discussion of sexual matters outside of strictly eugenicist paradigms had been severely curtailed by military censorship during the war years.[45] However, one of the first acts of the Occupation authorities was to order the Japanese Government 'to render inoperative the procedures for enforcement of peace-time and war-time restrictions on freedom of the press and freedom of communications.'[46] One unforeseen result was a 'veritable explosion'[47] of publications, many of them of a salacious and sensational nature. Referred to as 'the dregs' (kasutori), these low-brow broadsheets and magazines took advantage of the more liberal post-war environment to push the boundaries concerning representations of sex and romance. The newly purged Japanese authorities, for their part, tolerated what were called the three S's of 'sports, screen and sex,' as a kind of 'camouflage' to distract the population from the fact that the country was under occupation.[48] Indeed, one early magazine with the title Esu (S) expanded this list even further, advertising its contents as including 'Screen, Stage, Show, Sports, Style, Sing, Song, Story, Sense, Smile, Summertime, Step, Studio,' including last, but not least, 'Sex.'[49]

-

According to Yamamoto,[50] there were three different phases of the kasutori press. The first, from January to October of 1946 saw the emergence of magazines such as Riberaru (Liberal) which were influential in disseminating a new vocabulary of 'free choice' and 'romantic love' in intimate relations. However, it was Ryōki (Hunting for the bizarre) first issued in October 1946 that ushered in the more explicit genre of 'sex journalism.' From January of 1947, these magazines became ever more explicit in their discussions of sexual issues and more graphic, including photos and illustrations of semi-naked women which, from mid-year, increasingly included colour. The number of these magazines as well as the explicitness of their contents increased throughout the next eighteen months. From August 1948, new magazines such as Ōru ryōki (All bizarre hunt) began to publish complete female nudes and the number of such magazines in circulation reached the hundreds. The final phase of the kasutori press, which Yamamoto dates from June 1949 to May 1950 saw publications such as Fūfu seikatsu (Conjugal couple lifestyle) moving away from early post-war 'sexual anarchy' and more toward the 'sexual management' of the married couple.

-

The circulation and reach of the kasutori press is difficult to ascertain but Shimokawa Kōshi mentions that between 1946 and 1948 there were over 700 sex-related magazine and newspaper titles[51] and that although publications rapidly went out of print, new titles sprang up to feed the interest. Such was the demand that buyers would come to Tokyo and Osaka from the countryside in order to buy up copies to sell on at a profit.[52] Looking back on this period in 1953, journalist Narumigi Ichirō states that 'anyone could easily buy [obscene books and erotic materials] on the black market or at public gathering places.'[53] Bearing the above in mind, these publications clearly had a broad reach and were available in both urban and rural centres.

-

In terms of readership, a key market was male students who would read and discuss these articles communally in their dorm rooms.[54] However, women readers were also addressed in a number of general publications as well as in a variety of 'romance' magazines that appealed primarily to a female audience. For instance, in 1948 the Shinsō shinbun (True-tales news) featured a regular 'world of love' section which it advertised was 'edited solely by women'[55]—indicating an awareness of a female

| |

readership and the need for 'female perspectives.' Women also featured as authors and as participants in roundtable discussions that were transcribed and published in the press. These included the voices of 'respectable' women who discussed the implications of recent social reforms in terms of courtship and married life, as well as women who had been forced into a life of prostitution due to poverty and lack of other options in the immediate post-war chaos.[56] In fact the need for 'female perspectives' on a wide variety of topics, from 'first experiences' of courtship and lovemaking,[57] to prostitution and the practice of bedroom arts, was recognised.

Figure 2. Front cover of August 1948 edition

of the magazine Romansu (romance).

|

-

Although there was a distinctly heterosexual and masculinist bias behind the majority of the kasutori press in terms of the ownership and editorial policies of the magazines, it should be acknowledged that women's sexual and emotional experience during courtship and marriage was accorded a visibility not paralleled in pre-war discussions of these topics. The kasutori press was crucial in disseminating more widely knowledge about the mechanics of female sexual response that previously had only been available in medical and sexological publications. Significantly, the experiences explored were not always heterosexual or procreative in nature, as recognised in the title of one of the most notorious of the kasutori magazines: Ryōki, a term popularised during the 'ero-guro' boom of the 1920s[58] and meaning something like 'hunting for the (erotically) bizarre.'[59] Articles in this and similar magazines were interested in exploring the impact of the war and Japan's defeat upon the sexual sensibilities of both men and women. One theme frequently explored was the notion that Japan's defeat had created a nation of masochist men and sadist women.[60] The freedom with which the Japanese press under the Occupation was able to explore (and thereby disseminate information about) a wide range of heterosexual and non-heterosexual 'perversions' (hentai seiyoku) thus qualifies previous accounts of this period that have unduly stressed the conservative and restrictive effects of US sex and gender policies in Japan.[61]

-

Early post-war commentators frequently claimed that the main difference between pre- and post-war developments in 'sexual customs' (sei fūzoku) was that eroticism became 'democratized' (minshuka).[62] During the imperialist period, eroticism had been the province of 'professional' women who worked in segregated pleasure quarters since the eugenicist policies championed by the militarists had downplayed the role of romance and eroticism in married life. A hydraulic model of male sexuality acknowledged the 'necessity' of regular release for men, giving rise to the horrors of the military 'comfort women' system.[63] However, for married women, who were constantly exhorted to be 'good wives, wise mothers,' the role of sexuality was reduced to the making of babies—conceived of as a patriotic duty.[64] In an effort to shrug off such 'feudal' thinking, the early post-war press rapidly embraced the idea that women's new right to choose their own marriage partners required that ippan no josei or 'women in general' should have the right to exert agency during courtship and that women, too, had sexual needs.

-

To a large extent the emphasis on women's emotional and sexual rights within heterosexual coupledom represented a new 'cultural scenario,' the parameters of which had to be negotiated and defined. Hence, multiple authors stepped in to offer advice on how courtship might proceed and to define the new meanings associated with dating practices and lovemaking techniques. The didactic manner in which writers and editors sought to initiate young men and women into new, more 'modern' forms of coupledom and new, more 'democratic' expressions of desire is particularly striking. In the section below I will outline some of the ways in which early post-war authors sought to differentiate the 'new' or 'modern' couple from previous patterns of courtship behaviour.

The 'modern couple' in the popular press

-

The Japanese term for conjugal couple is fūfu, consisting of the characters for husband and wife. That the nature of coupledom was supposed to have changed was registered in the titles of several popular magazines first published in 1947, such as Shin fūfu (New conjugal couple), Modan fūfu (Modern conjugal couple) and the most enduring and well-read, Fūfu seikatsu (Conjugal couple lifestyle). The foreign loanword abekku (from the French avec or 'with') was used for a dating (but not yet married) couple that constantly appears in the title and body of articles about dating and courtship and which also appeared as the title of a popular magazine.

-

The term abekku had been in circulation in Japan as early as the 1920s and points to the fact that western ideas about courtship were already in circulation at that time. Yet, despite the fact that 'modern' forms of coupledom were being discussed in the press, 'the sight in the streets and in parks of young men and women walking with their arms locked together [was] a sight unknown before the

| |

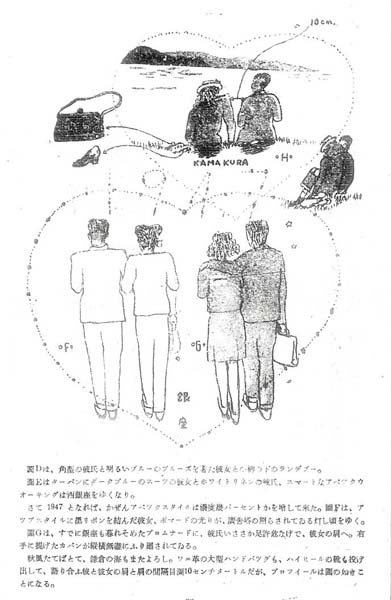

Occupation.'[65] However, during 1947 dance halls appeared offering abekku time at a reduced price, a new opportunity for male and female students to 'cheek dance' (to dance cheek-to-cheek) and move seductively to new rhythms. Such public dating practices proved bewildering for many, as can be seen from the many articles that appeared in the kasutori press documenting the phenomenon and also proffering advice on where to go[66] and how to behave on a date. For instance, a 1948 article on 'dating couples on the street'[67] analyses different kinds of abekku according to their clothes and accessories. The oddness of seeing men and women walking around the city streets in close intimacy was registered by the fact that the number of centimetres separating these different couples was recorded, as was the potential difficulty of maintaining a proper 'gait' (ashimoto) while walking alongside or 'arm in arm' with a partner.

Figure 3.Illustration of a seated abekku indicating the proper separation (10 cm) that decorum demanded, Raburii (Lovely), May 1948, p. 28.

|

-

Everything about the courtship process needed to be analysed and discussed in great detail, starting with the initial overture. For instance, a 'romantic-love studies seminar' offered in the December 1948 edition of Bēze (Kiss) proffered advice on how to write a love letter.[68] Having sought advice from a 'member of the intelligentsia with experience' in such matters, the author provides examples of an appropriate letter and response. His use of the term retā (letter) throughout, as opposed to the more familiar Japanese term tegami, indexes the way in which this kind of communication was considered part of a wider, and western-inspired, revisioning of courtship. Men and women were instructed on how to make an initial advance, given pointers toward appropriate venues for a date, and cautioned on when and how to walk, hold hands, and, frequently, to kiss. Given the previous lack of public display of kissing in Japan, the kasutori press was also keen to proffer advice on how to kiss: what to do with the tongue, where to look while kissing and, importantly, how long each kiss should last.

-

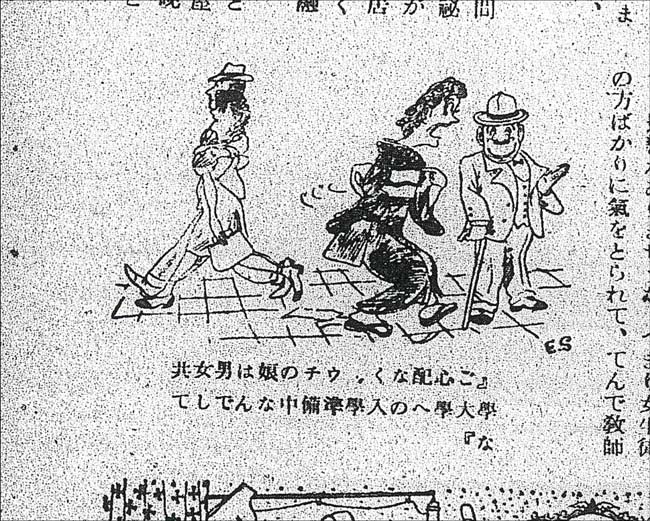

Much of this material was directed at women. For example, since the social significance of the kiss had to be clarified, a 1949 newspaper article debated whether or not a kiss from a man constituted a promise of marriage,[69] concluding that this American practice was simply a means of expressing friendly relations between the sexes. Women were a key constituency for this kind of advice in part because Occupation reforms had introduced co-education at Japan's public universities and thus young adult women were mixing unsupervised with men in larger numbers than ever before. The new social mix at co-educational colleges was the source of much humour in the press as can be seen in Figure 4, where the father's reply to a passerby outraged at the sight of his daughter strolling 'arm-in-arm' with a young man is, 'It's OK, she's just preparing for entrance to a co-ed university.'

Figure 4. 'Modern' couple walking abreast, from Modan Nippon, July 1946.

Figure 4. 'Modern' couple walking abreast, from Modan Nippon, July 1946.

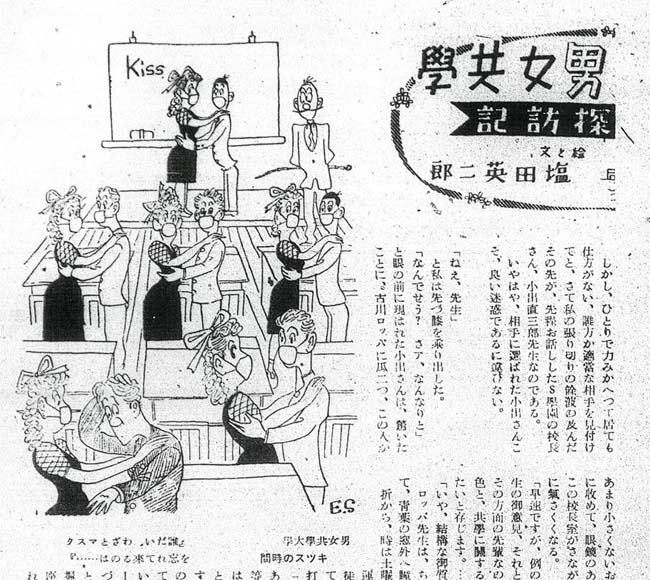

Figure 5. Humorous vision of a class at a 'co-ed' university, from Modan Nippon, July 1946.

Figure 5. Humorous vision of a class at a 'co-ed' university, from Modan Nippon, July 1946.

|

-

In this new more liberal atmosphere, the popular press did not shy away from offering instruction in the intimacies of sexual technique. Of overwhelming importance[70] in this discussion was the Japanese translation of Dutch gynaecologist Theodore Van de Velde's very explicit marital sex guide, originally published in English in 1929.[71] An earlier Japanese translation had been banned by the military authorities but in 1946 a newly abridged translation was issued under the title 'Ideal Marriage' (Kanzen naru kekkon) and widely excerpted in the press. Van de Velde had placed a great deal of emphasis on the need for simultaneous orgasm in the context of an ideal relationship and had gone into great detail explicating (with charts and diagrams) the differences between the onset, peak and duration of male and female climaxes. Van de Velde's influence was reflected in many articles in the kasutori press on the theme of 'sexual technique,' by which was meant techniques that men should practice in order to bring about orgasms for their female partners.[72] Indeed, the need for the 'sexual satisfaction' (sei manzoku) of both partners became a key symbol of the new equality between the sexes and sexual satisfaction became an important way to differentiate between feudal and modern forms of coupledom. As Yamamoto (who was a high school student at the time) observes, such discussions had the effect of challenging the previous notion that 'sex for pleasure' was something only engaged in with professional women in the context of the brothel district, reinforcing the new idea that eroticism was an important expression of affection between couples in general.[73]

-

The tone of these many discussions was matter-of-fact and instructional, women being regarded almost as machines in need of fine-tuning by their technician partners. In a typical article on 'sexual love techniques' published in December 1947, for instance, it was noted that female frigidity was the result of a lack of skill on the part of a woman's male partner, particularly insufficient foreplay. The average length of intercourse, at three minutes, was judged insufficient for female pleasure and it was suggested that men's lack of interest in female pleasure was 'ungentlemanly' and reflected poor etiquette. Male readers were encouraged to study the charts depicting the onset and development of male and female orgasm (lifted from Van de Velde) and to regulate their own climaxes so as to better optimise ideal conditions for the climaxes of their partners.[74]

-

Despite the mechanistic, technical tone of many of these articles, the stress on the need for female sexual response was an innovation that challenged the previous regime's emphasis on the requirement of female chastity. Women writers, too, endorsed the need for women's active participation in the bedroom.[75] During wartime, women who sought out 'illicit' love affairs had been regarded by the authorities 'not only as antiwar, but as threatening the fabric of Japanese society.'[76] However, as Christine Marran notes, the kasutori press was influential in disseminating 'anecdotes and interviews to prove not the perversity but rather the normalcy of female sexual desire.'[77] The new discourse posited sex as a recreational activity to be enjoyed equally by both partners. 'Sexual love' (sei ai) was inscribed as a central aspect of the new 'romantic-love marriage system'[78] and was discussed with reference to an eclectic survey of erotic texts from around the globe, including India and China as well as more recent sexological surveys in European languages. These authors attempted not only to expand the range of sexual practices (as well as the duration of the sex act) but also to expand the definition of the sexual. A 1949 article subtitled 'Sex life from the perspective of the nose,' for instance, discussed a range of scents that had traditionally been used as aphrodisiacs in an effort to encourage couples to experiment with and enjoy the smell of their partners.[79]

Sexual scripting and sexual practice

-

It is of course problematic to read these exhortations in the popular press to practice sex more 'democratically' as a clear indication of shifts in actual practice. However, if Simon and Gagnon are correct in pointing toward the importance of broad cultural shifts in the 'scripting' of sexual behaviour, we would expect to see shifts in the discursive environment reflected in actual life. There is some evidence that this is the case, presented both by commentators writing at and near to the time as well as in later surveys.

-

For instance in a 1954 discussion in popular sexological magazine Amatoria, sex journalist Kabiya Kazuhiko and influential medical doctor/sexologist Ōta Tenrei (an early champion of contraception) looked back on the sudden uptake of 'petting' among young couples in post-war Japan. Ōta disagreed with other sexologists who had, apparently, claimed that such acts as kissing and petting were unknown in Japan before the war's end. However, he claimed that petting had been practiced only as a prelude to intercourse. He argued that what was new in the post-war context was the adoption of petting practices by abekku or dating couples as a recreational activity, not necessarily as a prelude to coitus.[80]

-

This shift in attitudes toward the meaning and practice of sex is also evidenced to some extent by the results of a 1982 survey into the timing and nature of respondents' first sexual intercourse.[81] The report's authors note that in the immediate post-war period, discussion of the 'loss' of chastity (teisō or otome for women and dōtei for men) was replaced by the more neutral and gender equivalent 'hatsu taiken' (first experience), reflecting the decreased value placed on preservation of virginity, especially for women.

-

These data show some interesting generational differences in the type of partner chosen by men.[82] Although the response rate of 488 individuals (including only 59 women) is clearly too small to make definitive statements, the report's authors do support their findings with qualitative data from the questionnaire and make some attempt to interpret these findings in their historical context. The authors divide responses into five age cohorts (from 60s through 20s) but discover the most meaningful divisions to be between those generations who came of age in the pre-war, wartime and post-war periods since each of these three periods was characterised by a different kind of sexual culture, or to use Simon and Gagnon's term, sexual scripts.

-

For instance, the authors point out that the generation over 60 would have come of age well before the outbreak of the Pacific War at a time when the pleasure quarters were still an integral part of male socialisation. They note that for men of this generation, recreational sex was viewed as a commercial transaction and that the majority of men in the survey were inducted into sexual activity by professional prostitutes, often at the instigation of older peers (one man recalls being taken to a geisha house by his father). One respondent writes:

My first experience took place in the Nakamura pleasure quarters in Nagoya when I was 17. My partner was a prostitute aged around 25. She saw through my virginity and explained many things to me.[83]

-

Not all prostitutes were as accommodating of their customers' naïvety, however, and most respondents recall that the sex was extremely perfunctory, and was performed in a quick and business-like manner. One respondent recalling his first visit at age 16 to the 'pleasure' quarters in a Manchurian city, remembers being pushed down on the bed and straddled by a prostitute with no preparation. As this was taking place, he remembers thinking 'masturbation is better than this.'[84]

-

The authors note that male respondents who came of age in the pre-war and wartime periods commonly reported sexual initiation with prostitutes in their mid-to late-teens since at this time 'loss of virginity' (dōtei hōki) was a rite of passage for adolescent boys. Although some respondents who came of age after the war still report first-time experiences with professional women, the report's authors point out that sexual mores (sei fūzoku) had changed and that men now preferred to seek out liaisons with shirōto onna, literally 'amateur' but in this context best translated as 'respectable' women.[85] Indeed, by the 1970s, editorials in Japan's Playboy magazine were arguing that men whose only sexual experiences had been of a commercial nature were still 'shirōto dōtei,' that is, virgins in regard to non-professional women. An alternative designation posited these men as 'half virgins' (han-dōtei), suggesting that by this time sex, in order for it to count, had to be freely given by a woman unconnected with the floating world of bars and prostitution. That sexual experience alone no longer indicated a loss of virginity, points to the heightened value that was placed upon the need for courtship and the establishment of more equitable male-female relationships among men of the postwar generation.[86]

-

The evidence presented above, when placed alongside the discussions already cited from the kasutori press, does suggest that there was a significant shift in the 'scripting' of sexuality in the early post-war environment. Despite the fact that licensed prostitution continued in Japan until 1957, no longer was it a matter-of-fact occurrence that young men should lose their virginity as a rite of passage in the pleasure quarters. Instead, much more emphasis was placed upon the pursuit and successful courtship of 'respectable' women, an enterprise that required the development of a new set of social skills and behaviours, not just the exchange of money. Also the meaning of 'sex' was expanded from the rapid and somewhat perfunctory performance of coitus to include more leisurely and recreational practices including kissing and petting.

Conclusion

-

According to cultural historian Tsurumi Shunsuke, 'for people at large, the most durable influence of the Occupation was on the Japanese life style, especially with respect to relationships between women and men.'[87] This influence was exerted in a number of ways, not least by a range of structural changes to the organisation of Japan's work, education and family life. However, also of importance were a range of 'soft power' initiatives such as the screening of Hollywood romance movies and interventions into the scripting and production of home-made Japanese dramas. The silver-screen 'love scenes' that became such a talking point in the popular press were also evident in real-life venues as American service personnel, both male and female, demonstrated new ways of fraternising in public space.

-

The kasutori press offered a venue where a range of new 'scenarios' and 'scripts' structuring sexual activity could be discussed and the meanings associated with love, marriage and eroticism debated. The rhetorical linkage between democracy and romance, conceived as a 'liberation' of the public and private spheres respectively, enabled writers and readers to position themselves as modern and liberated in relation to the 'feudalism' of the previous regime. 'Sex journalism' was a prevalent feature of the early post-war period, suggesting that there was a rapid (although arguably not enduring) change in the rhetorical environment in which sex and romance were discussed. New 'sexual scenarios' eventuated which had some impact on male-female relationships.

-

Although feminist historians such as Kathleen Uno have argued that the 'good wife, wise mother' ideology survived Japan's defeat and occupation, and continued well on into the 1980s,[88] as Marran points out, the immediate post-war years, at least, were a time when this concept 'played little role ideologically.'[89] Rather, at this time, imperialist eugenic paradigms that had associated the sex act exclusively with fertility and denied women sexual agency or desire were challenged by new discourses insisting on the 'sexual satisfaction' of both partners as an essential element of an 'ideal marriage.' Furthermore, the meaning of 'sex' was expanded from a narrow definition of coitus to include broader, recreational activities such as kissing and petting, activities that were now viewed as legitimate practices that could be enjoyed by dating couples. Indeed, sexologist Takahashi Tetsu claimed that engaging in such practices was a way for young men and women to become 'instant democrats' and establish their modern credentials.[90]

-

It has been impossible in this short overview to give a full account of the changes in the cultural environment structuring sexuality in the early post-war period. The kasutori press under discussion was but one of a range of competing genres that sought to give new meaning to male-female relationships. However, there has so far been almost no discussion in English-language scholarship of the effects that this widespread and popular genre had upon embodied experience and it is to be hoped that much more attention will be given over to this extensive archive in the near future.[91]

Endnotes

[1] Igarashi Yoshikuni, Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945?1970, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 47.

[2] For a discussion of the literature of this period, see Roman Rosenbaum, 'The generation of the burnt-out ruins,' in Japanese Studies, vol. 27, no. 3 (2007):281–93.

[3] Takeda Hiroko, The Political Economy of Reproduction in Japan: Between Nation-State and Everyday Life, Oxon: Routledge Curzon, 2005, p. 41.

[4] Igarashi, Bodies of Memory, p. 53.

[5] Igarashi, Bodies of Memory, p. 48.

[6] For a detailed discussion of the rise of this discourse of 'free love,' see Mark McLelland, 'Kissing is a symbol of democracy!: Dating, democracy and romance in Japan under the occupation 1945–52,' in The Journal of the History of Sexuality, forthcoming 2010.

[7] For a detailed discussion of the genre see Yamamoto Akira, Kasutori zasshi kenkyū: shinboru ni miru fūzoku shi, Tokyo: Shuppan nyūsusha, 1976.

[8] See for instance Lisa Yoneyama, 'Liberation under siege: U.S. military occupation and Japanese women's enfranchisement,' in American Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 3 (2005):885–910.

[9] An important exception is Christine Marran, Poison Woman: Figuring Female Transgression in Modern Japanese Culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, pp. 136–46.

[10] These reforms were, of course, limited by the restrictive thinking about women's abilities and status at the time. Mire Koikari, 'Rethinking gender and power in the US Occupation of Japan, 1945–1952,' in Gender & History, vol. 11, no. 2 (1999):313–35, stresses that the new roles for women encouraged by the Occupation were still very conventional, and tied in with images of 'white, middle-class progressive motherhood.'

[11] Susan Pharr, 'The politics of women's rights,' in Democratizing Japan: The Allied Occupation, ed. Robert Ward and Yoshikazu Sakamoto, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987, pp. 221–52, p. 241.

[12] Nishi gives a summary of fifteen categories of articles commonly suppressed by the Occupation's Civil Censorship Detachment, none pertaining to morals. Nishi Toshio, Unconditional Democracy: Education and Politics in Occupied Japan 1945–1952, Stanford University: Hoover Institution Press, 1982, p. 101.

[13] Joanne Izbicki, 'Scorched Cityscapes and Silver Screens: Negotiating Defeat and Democracy through Cinema in Occupied Japan,' PhD dissertation, Cornell University, 1997, p. 137.

[14] See for example Kiwa Kōtaro, 'Rabu shiin mangen,' in Eiga yomimono, vol. 2, no. 5 (1948):18–20, p. 19.

[15] Junesay Idditie [Junsei Ijichi], When Two Cultures Meet: Sketches of Postwar Japan, 1945–1955, Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1955, p. 143. For a discussion of the 'kissing debate' in relation to film of the period, see McLelland, 'Kissing is a symbol of democracy!'

[16] Kyoko Hirano, Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation, 1945–1952, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992, p. 162.

[17] Izbicki, Scorched Cityscapes and Silver Screens, p. 136.

[18] See for example, Kanda Setsuko, Shibuya Chikako and Kitamura Chieko, 'Ren'ai to kekkon to arubaito wo kataru,' in Seishin seikatsu, January (1949):67–71.

[19] William Manchester mentions that these radio discussions were considered so important that radio sets were placed in public areas to encourage listeners, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964, Boston: Hutchinson, 1978, p. 511.

[20] Tsurumi Shunsuke, A Cultural History of Postwar Japan: 1945–1980, London: Kegan Paul International, 1987, p. 11. For a discussion of pre-1945 limitations on male-female interaction in Japan see Ronald Dore, City Life in Japan: A Study of a Tokyo Ward, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1958, pp. 159–62.

[21] See Robert Whiting, Tokyo Underworld, New York: Vintage Books, 2000, pp. 12–14, for a description of the scale of early post-war prostitution.

[22] Yamamoto, Kasutori zasshi kenkyū, p. 56.

[23] Takahashi Tetsu, Kinsei kindai 150 nen sei fūzoku zushi, Tokyo: Kubo shoten, 1969, p. 273.

[24] Narumigi Ichirō, 'Sekkusu kaihō no ayumi: tenbō 1945–1953,' in Amatoria, June (1953):40–51.

[25] Just some of the hundreds of magazines containing such articles, all in print between 1946 and 1949, include: Shin fūfu (Modern couple), Riibe (Freedom), Bēze (Kiss), Momo iro raifu (Pink life), Abekku (Couple), Ai (Love), Danjo (Man and woman), and Hanashi (Chat).

[26] Marran, Poison Woman, pp. 140–41.

[27] Although some pointers are given later in the text, it is outside the scope of this paper to discuss the range of readership of the kasutori press. Although the salacious nature of much of the material might suppose an exclusively 'low-brow' authorship and readership, this is demonstrably not the case. Firstly, a number of well-known intellectuals such as journalist and publisher Kikuchi Kan and sexologist Takahashi Tetsu published in these magazines, see for example Kikuchi Kan, 'Ren'ai kekkon seidō,' in Hanshi, August 1948, (page number missing from copy), and Takahashi Tetsu, 'Kekkon hatsu yoru to hanemūn,' in Seishun seikatsu, August 1949, pp. 18–20. Secondly, a key audience for this new discourse on courtship and sexual technique was comprised of male (and some female) university students, a small but élite class; and finally, given the complex manner in which the 'liberation' of women and sexuality were aligned with the wider democratisation process, there was a great deal of philosophising that included references to a range of 'high-brow' western theorists, most prominently Jean-Paul Sartre and from 1949 on, Alfred Kinsey.

[28] Mariam Silverberg, Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Modern Times, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

[29] Shibaki Bunya, Seppun nenpyōki, Tokyo: Kindai bunkōsha, 1949, p. 166.

[30] Yamamoto Akira, 'Kasutori zasshi,' in Shōwa no sengoshi, ed. Saburō Ienaga, Tokyo: Chōbunsha, 1976, p. 244.

[31] See Fukushima Jūrō, Sengo zasshi no shūhen, Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, 1987, pp. 239–64, and also McLelland 'Kissing is a symbol of democracy!' for a discussion of the effect the lifting of wartime censorship had upon sexual expression in the popular press.

[32] William Simon and John Gagnon, 'Sexual scripts: origins influences and changes, in Qualitative Sociology, vol. 26, no. 4 (2003):491–97, p. 492.

[33] John Gagnon and William Simon, Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality, London: Hutchinson, 1973, p. 105.

[34] Gagnon and Simon, Sexual Conduct, p. 105.

[35] Gagnon and Simon, Sexual Conduct, p. 105.

[36] Foucault, Michel, The History of Sexuality volume 1, London: Penguin, 1990, p. 127.

[37] Martin, Fran, Situating Sexualities: Queer Representations in Taiwanese Fiction, Film and Public Culture, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2003, p. 251.

[38] Gagnon and Simon, Sexual Conduct, p. 106.

[39] Gagnon and Simon, Sexual Conduct, p. 111.

[40] Gagnon and Simon, Sexual Conduct, p. 111.

[41] Igarashi, Bodies of Memory, p. 58.

[42] See Yuki Tanaka, Japan's Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation, Oxon: Routledge, 2002, chapters 5 and 6.

[43] Narumigi, 'Sekkusu kaihō,' p. 48

[44] Shibusawa describes the vulnerable legal as well as emotional and financial position these women found themselves in. Since US personnel in Japan had legal immunity, it was not possible for Japanese women to serve paternity writs on the men who had made them pregnant. See Naoko Shibusawa, America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008.

[45] Japanese wartime propaganda 'portray[ed] Japan as the antithesis of the supposedly sexually deviant and lascivious westerner,' instead stressing 'a vision of home front chastity,' see Barak Kushner, The Thought War: Japanese Imperial Propaganda, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006, p. 63.

[46] See Jay Rubin, 'The impact of the occupation on literature or Lady Chatterley and Lt. Col. Verness,' in The Occupation of Japan: Arts and Culture, ed. Thomas W. Burkman, Norfolk, Virginia: General Douglas MacArthur Foundation, 1988, pp. 167–74, p. 169.

[47] Rubin 'Impact of the Occupation, p. 169.

[48] Kōno Kensuke, 'Hihyō to jitsuzon: sengohihyō ni okeru sekushuariti,' in Kokubungaku kaishaku to kyōzai no kenkyū, vol. 40, no. 8 (1995):44–51, p. 46.

[49] Front cover of Esu, June 1948.

[50] Yamamoto, Kasutori zasshi kenkyū, pp. 32–33.

[51] Shimokawa Kōshi, Nihon ero shashinshi, 1995, Tokyo: Seikyūsha, p. 32.

[52] Goichi Matsuzawa, 'Kasutori zasshi to 'Garo' no Nagai-san,' in Sei media 50 nen, Tokyo: Takarajimasha, 1995, pp. 23–31, p. 30.

[53] Narumigi Ichirō, 'Sekkusu kaihō,' p. 41.

[54] Yamamoto, Kasutori zasshi kenkyū p. 48.

[55] Shinsō shimbun, 'Onna bakari de henshūshita ai no sekai,' 15 April 1948, unpaginated.

[56] See for example 'Panpan zadankai: waga mune no soko niwa,' in Ai, April (1948):36–41.

[57] See for example 'Kekkon hatsu yoru wo kataru,' in Seishun romansu, July (1949):25–27. This discussion included three women out of a panel of six.

[58] For a prewar history of the term see Jeffrey Angles, 'Seeking the strange: Ryōki and the navigation of normality in interwar Japan,' in Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 63, no. 1 (2008):101–41.

[59] One common theme running through the depiction of 'perverse' sexual desires in the kasutori press is the rise of 'sadistic women' (linked with lesbianism) and 'masochist men' (linked with cross-dressing prostitution), both conditions diagnosed as a result of Japan's defeat and the supposed collapse of the traditional sex/gender system following on from Occupation reforms. See McLelland, Queer Japan from the Pacific War, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005, ch. 2.

[60] See McLelland, 'From sailor-suits to sadists: Lesbos love as reflected in Japan's postwar "perverse press",' in U.S.-Japan Women's Journal, no. 27 (2004):27–50. So far, researchers have discussed the impact of Japan's defeat only on heterosexual relations, particularly the crisis of heterosexual male identity. However, researchers working on early postwar literature, particularly the work of Ōe Kenzaburō, have noticed his deployment of homosexual male characters to signify a defeated Japanese masculinity; see for instance Margaret Hillenbrand, 'Doppelgangers, misogyny, and the San Francisco system: the occupation narratives of Ōe Kenzaburō,' in Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 33, no. 2 (2007):383–414; and Iwamoto Yoshio, 'Ōe Kenzaburō's Warera no jidai (Our Generation): sex, power and the other in Occupied Japan,' in World Literature Today, vol. 76, no. 1, Winter (2002):43–51.

[61] See in particular Mire Koikari, Pedagogy of Democracy: Feminism and the Cold War in the US Occupation of Japan, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008, who considers the occupation-time sexual dynamics as symptomatic of Cold War containment politics but without ever attending to the early post-war boom in 'queer' (hentai) sexual networks and discourse and the large impact that gay US servicemen had upon nascent indigenous homosexual identities at this time. Shibusawa reinforces this heterosexist bent when she focuses solely upon the importance of US-Japanese heterosexual relations in 'reimagining the Japanese enemy.' However, American gay men too, as lovers, scholars and translators, played an important role in this process of revisioning from the earliest days of the Occupation. Shibusawa does note however, that in the American journalistic imagination at least, Japanese men were sometimes represented as effeminate and tending toward homosexuality. It is important to stress that the Japanese press at the time was also making these observations, particularly in regard to the upsurge in male cross-dressing prostitution; see Shibusawa, America's Geisha Ally, p. 131. For an alternative account stressing the relative plasticity and openness of this period from a sexual-minority perspective see Hitoshi Ishida, Mark McLelland and Takanori Murakami, 'The origins of "queer studies" in postwar Japan,' in Genders, Transgenders and Sexualites in Japan, ed. Mark McLelland and Romit Dasgupta, London: Routledge, pp. 33–48, and Mark McLelland, Queer Japan, chapters 2 and 3. For a discussion of the influence gay American men have had upon western perceptions of Japanese culture as effeminate, see Sheila Johnson, The Japanese through American Eyes, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991, p. 89 and John Treat, Great Mirrors Shattered: Homosexuality, Orientalism and Japan, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

[62] See for example, Hasegawa Ryō and Takagi Takeo. 'Senzen sengo ero sesō ōdan,' in Amatoria, April (1953):159–63, p. 60. A similar point is made in the 'Nihonjin no 'hatsutaiken' ni kan suru' report discussed below.

[63] George Hicks, 'The ?comfort women,"' in The Japanese Wartime Empire 1931–1945, ed. Peter Duus, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996, pp. 305–23.

[64] See Sabine Frühstück, Colonizing Sex: Sexology and Social Control in Modern Japan, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003, p. 167; Jennifer Robertson, 'Blood talks: eugenic modernity and the creation of new Japanese,' in History and Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 3 (2002):191–216, p. 199; Takeda, Political Reproduction, p. 41.

[65] Junesay, When Two Cultures Meet, p. 138.

[66] See Suzuki Toshihiko, 'Abekku no seiteki kyōraku annai: Abekku de tanoshimu basho wa dokoka?,' in Kibatsu zasshi, November (1949):25–27.

[67] Yoshida Kenkichi, 'Gaitō abekku sanpuru,' in Raburii, June (1948):29–30.

[68] Ōnishi Kōichi, 'Ren'aigaku kōza: raburetā no kakikata ni tsuite,' in Bēze (Kiss), December (1948):31.

[69] No author, 'Kissu wa kekkon no techō ka: jiyū ren'ai no echiketto,' in Tokyo Yomimono Shinbun, February (1949):4.

[70] Various versions of Van de Velde's text were constantly reprinted during the postwar period and it remained in print until 1982. Ishikawa Hirogi argues that Van de Velde's textbook was the origin of the 'how to sex' articles still common in men's magazines in Japan, see Ishikawa Hirogi, '"Kanzen naru kekkon" kara ?HOW TO SEX" e no sengo shi,' in Kurowassan, July (1977):113–15.

[71] Several versions were in circulation but the most popular (on account of its readability) was an abridged version published as Ban de Berude [van de Velde], Kanzen naru kekkon, Tokyo: Fumotosha, 1947, which became a best seller.

[72] See Fukushima, Sengo zasshi no shūhen, pp. 246–47 for a discussion of the influence of Van de Velde on popular sex journalism.

[73] Yamamoto, Kasutori zasshi kenkyū, p. 51.

[74] Tatsumi Gōta, 'Sei ai no gikō: Hisuterii wa otto no sekinin de aru,' in Raburii, December (1947):35–37.

[75] See female writer Irie Kōōshi's short story, 'Kanzen naru kekkon,' in Seishun romansu, July (1949):12–19.

[76] Barak Kushner, The Thought War, p. 185.

[77] Marran, Poison Woman, p. 136.

[78] See for instance the many articles in the 'romantic-love marriage system' special edition of the August 1948 edition of the magazine Hanashi (Talk).

[79] Ōya Masatake, 'Fūfu seiai tokuhon: hana kara mita seiseikatsu,' in Shin fūfu, August (1949):25–28.

[80] Ōta Tenrei and Kabiya Kazuhiko, 'Petchingu wa ryūkō suru,' in Fūzoku kagaku, March (1954):79–83.

[81] Dai ni ji shin seikatsu kenkyūkai hensanbu hen (eds), 'Nihonjin no 'hatsutaiken' ni kan suru sedai betsu ankeeto chōsa,' in Sei seikatsu hōkoku, August (1982):28–42.

[82] Dai ni ji shin seikatsu kenkyūkai, 1982.

[83] Dai ni ji shin seikatsu kenkyūkai, 1982, p. 30.

[84] Dai ni ji shin seikatsu kenkyūkai, 1982, p. 30.

[85] Dai ni ji shin seikatsu kenkyūkai, 1982, p. 36.

[86] Shibuya Tomomi, Nippon no dōtei, Tokyo: Bungei shunju, 2003, pp. 139–40.

[87] Tsurumi Shunsuke, A Cultural History of Postwar Japan, p. 11.

[88] Kathleen Uno, 'The death of "good wife, wise mother"?' in Postwar Japan as History, ed. Andrew Gordon, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, pp. 293–323.

[89] Marran, Poison Woman, p. 201, n. 1.

[90] Takahashi, Kinsei kindai 150 nen, p. 273.

[91] The archival material discussed in this paper is derived from the author's extensive collection of kasutori titles, selected titles housed in the Gordon W. Prange collection of Japanese magazines at the University of Maryland and the originals reprinted in Shimbun shiryō raiburarii, (ed.), Kasutori shimbun: Shōwa nijūnendai no sesō to shakai, Tokyo: Ōzorasha, 1995.

|