Tour Performance 'Tokyo/ Olympics':

Digging the High Times of the 1960s

Peter Eckersall

Olympic Games, 1960s

He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging.

Much of today's Japanese performing arts need to be analyzed in terms of the social, economic, and political actualities of globalization.

Uchino Tadashi [2]

-

In December 2007, Tokyo-based performance group Port B (Poruto Bii) staged 'Tokyo/Olympics' (Tōkyō/Orinpikku), a seven-hour bus tour taking in sites relating to the staging of the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. The company is named after the Spanish border town Portbou where Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) ended his life. For this mobile performance art event, called a 'tour performance' following in the tradition of site-specific theatre, Port B contracted Hato Bus, a well-known Tokyo-based tour company. Travelling on one of Hato Bus's distinctive bright yellow buses, 'Tokyo/Olympics' reproduced the performative, spatial and durational characteristics of a typical Japanese sightseeing tour.

-

In this essay I examine how 'Tokyo/Olympics' (see Figure 1) explores Tokyo's cultural history from the 1960s era, a time of prosperity and optimism for which the Olympic Games stands as an indexical sign.

My reading will explore the city as a theatrum mundi where themes such as nationalism, consumption, gender and public space intersect and are transhistorical. A theatrum mundi is a Baroque term meaning theatre of the world, suggestive of Shakespeare's famous line 'All the world's a stage…' and redolent with the notion that the everyday is performative. I also consider how Port B uses techniques of documentary theatre to uncover the past, not to dwell on the detritus of history, but to reconsider life in present-day Japan when people face new challenges and problems.

Figure 1. 'Tokyo/Olympics' poster, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 1. 'Tokyo/Olympics' poster, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

|

-

Using Benjamin's idea of digging as a way of thinking about history in composite terms in relation to the Olympics, recalls an era of high economic growth and the first wave of postwar optimism. To briefly list some of the achievements of these 'high times' of the 1960s: during this decade, Japan's postwar reconstruction was largely completed. Even working-class people bought televisions and small cars. Japan's Olympic Games was the first to be held in a non-western country. In the opening ceremony, Sakai Yoshinori, an athlete from Hiroshima born on 6 August 1945, the day the first atom bomb was dropped, lit the Olympic flame.[3] An abiding interest in science and technology saw advances in electronics and the beginnings of Japan's high-tech economy: the Olympics were beamed live across the Pacific in some of the first television transmissions via satellite. High-speed Shinkansen train lines, expressways, new cosmopolitan hotels and striking modernist architecture visibly transformed the city and countryside. From the vantage point of 1964, everything seemed possible.

-

As will be seen, though, 'Tokyo/Olympics' offers a strong critical stance towards Japan's recent history. Partly this stance is about the perceived problem of historical revisionism, a problem arising when interpretations of history excise parts that do not fit contemporary narratives of power. This is evident in debates over school textbooks and their treatment of Japanese aggression in World War Two, for example.[4] Partly too, it is about the far-reaching disappearance of historical perspectives on the everyday, a 'vanishing' to adopt Marilyn Ivy's term describing Japan's peculiar 'phantasmic' experience of modernity. Her Jamesonian take on vanishing aspects of Japan's postwar culture explores how their disappearance returns as a form of haunting nostalgia; something that will not go away and which sometimes finds surprising new adjustments with postwar modernity. This is a perspective that 'Tokyo/Olympics' relates to postmodern capitalism and theories of commodification as a powerful force in Japan.[5] Accordingly, history—that which gives a sense of the complexity of culture and politics—is depoliticised and flattened into a function of the market to be packaged (and perpetually repackaged) as a form of empty nostalgia.

-

I argue that Port B's efforts to activate a sense of historical awareness among audiences cuts a swathe through the socio-political terrain of the city of Tokyo, a 'site' that is explored in terms relevant to globalisation studies. Tokyo's decentered urban design, interstitial life-work practices, prominence in aesthetic innovation and dominance in the global economy all contribute to the notion of the city as a key site for the experience of globalisation. Contemporary arts are an aspect of this perspective evolving playful and acerbically 'flat' (superficially two-dimensional) aesthetic forms in a critical mirroring of city life.[6] Moving through the city on the Hato Bus tour, moreover, connects Tokyo to the theme of embodiment. Being ordered as tourists we are consciously reminded that it is our bodies that are moving in the performance. Tour guides motivate this corporeal relationship. They coordinate the immediate dramaturgy of the performance by keeping track of the audience-participants and filling gaps when the bus is struck in traffic. Some scenes explore how this is a gendered performance functioning to ensure a smooth-running encounter with the city. As for the idea of history, informed by Benjamin's writing as alluded to above, I take this as a dramaturgical premise as well as a theoretical framework. Benjamin's perspective of 'entering' history, as fragmentary memories connecting human sensations with politics and art, is not able to be extricated from the conditions of the performance and will be discussed within the extended analysis below. The essay will conclude with reference to the idea of history repeating; restaged in performance as well as in the world at large. 'Tokyo/Olympics' is a composite examination of Japan's socio-political experience of the Olympic Games. After cancelling the Olympics in the 1940s in wartime, the 'proud spirit' of 1964 is being revived in Tokyo's current bid for the 2016 Games. Before discussing 'Tokyo/Olympics' it is helpful to introduce some theoretical perspectives on performance, bodies and globalisation and relate them to the Port B company.

Reassessing power relations: theoretical perspectives on history and performance and the background to Port B

-

Liveness helps define the unique qualities of performance. Consequently, exploring questions about temporality and capturing the significance of the ephemeral are key concepts in performance studies. Appreciating the dialectical nature of performance—making sense finally in interactions with an audience, or with society and culture more broadly—gives it a strong interdisciplinary focus. Of all the art forms, the performing arts are particularly wedded to contextual analysis. Moreover, the term performance is applied broadly to social and political analysis. As Marvin Carlson notes: '[w]ith performance as a kind of critical wedge, the metaphor of theatricality has moved out of the arts into almost every aspect of modern attempts to understand our condition.'[7] Performance theorists' view performance as a liminal activity that connects community practices with art, thereby enabling a 'space between analysis and action…to pull the pin on the binary opposition between theory and practice.'[8] This liminal capacity of performance to move between more straightforward acts of mimesis on the one hand and abstraction on the other offers inventive composite ways of relating to and understanding our experience of the world. To this end, I argue here that 'Tokyo/Olympics' rides between moments of artistic invention and something that is more consciously about the experience of living.

-

In developing this point, Port B dramaturg Hayashi Tatsuki notes how staging 'Tokyo/Olympics' outdoors is a basis for reassessing power relations in theatre. Leaving the security of the theatre stage calls into question 'self-evident relations in theatre such as seeing/being seen or acting/receiving,' he argues.'[9] Breaking into binary systems of theatre's presentational aesthetics and reception by way of a hybrid mixing of art and the everyday can offer new perspectives for understanding history. As Baz Kershaw notes, such ideas in performance posit grounds for the reappraisal of meaning of historical events.

Such hybridity transforms the processes of performance into a negotiation between the performers and audience about how explicit the problematisation of the present by the past might become. If the problems are subdued…nostalgia and the commodity reign; but if they become explicit then a fresh relationship is created between present and past because history is being newly created, as multiple histories come into play.[10]

Hayashi would likely agree with Kershaw when he argues that in 'Tokyo/Olympics': 'the audience becomes creator when their assumptions about the performance are challenged and there is a clashing against what the performance offers. Into this gap, people start to make their own sense of the experience.'[11]

-

'Tokyo/Olympics' asks questions about the meaning of the Olympic Games and more broadly focuses on what Maurice Roche calls one of the 'mega-events' in the formation of postwar capitalism and globalisation. The introduction of new mediums of communication and modes of economic exchange such as satellite broadcasts and a wholesale makeover of the city into the very image of a techno-metropolis reveal the 1964 Games to be on the cusp of a global transformation. Roche reflects on developments connected with Tokyo's Olympic transformation, writing that: 'On the basis of these…techno-economic infrastructures, the capitalist economy has been integrating…and "globalising" at a rapid rate.'[12] Globalisation is a system that organises through the production of social and cultural activities with everything imbricated in and by its decentered mode of power.[13] On this basis, the Olympics signals wider shifts in the cultural and economic fabric of Japan as precursor to and indication of the direction of Japan's globalisation. These are points that the performance explores.

-

Port B was founded in 2003 by Takayama Akira as a loose-knit group of artists, scholars and activists. Takayama studied theatre theory in Germany, but many Port B members have neither professional training nor prior study in theatre and come from diverse walks of life. They produce works spanning experimental theatre pieces, documentary style 'tour performances' and art installations. Most of these have a deconstructionist aspect that foregrounds performance as a form of research in equal measure to it being an experience to engage audiences. Takayama relates his work to Bertolt Brecht and the need to 'reactivate the role of the audience…(towards a) more critical and creative role in their reception (of theatre).'[14] As with Brecht, Port B's performances are dialectical and propose to activate the audience in debates about art and the contemporary condition.

-

The dialectical relationship between art and society is complicated to analyse and a conundrum exists for the performing arts in relation to globalisation. This has changed performance at an almost ontological level of operation. To briefly explain, theatre thrives in local contexts where human scale events tap into stories and experiences are mediated through live intimate encounters. Ironically, the cultural economy of globalisation thrives on presenting these local 'authentic' experiences and many artists rely on financial support from international producers to produce new works. Thus, while the global matrix is an extremely fertile ground for artistic production, this is mitigated by fundamental characteristics of performance being expressed through live bodies in grounded settings. The more one enters the global, the less chance one has of accessing the uniquely local. 'Tokyo/Olympics' straddles this conundrum in interesting ways. Drawing from Benjamin and Brecht, it connects to the 'archive' of modern theatre history and aims to bring about a productive exchange of shared, even revolutionary ideas about transforming the world. Conversely, from a dramaturgical perspective, 'Tokyo/Olympics' is local and temporal; the singular experience of touring the city is the theatrical content. It also blurs the boundary that is usually drawn between art and the everyday. Takayama uses non-theatrical materials, such as the bus tour as a real world performance genre to shift audience expectations. He notes that: '[i]nteractions between the genres (Hato bus tour/theatrical event, Tokyo/Olympics) was a new strategy to facilitate a sense of interference and hence to connect personal experiences with social dimensions.'[15] This statement by Port B's director confirms the company's primary interest in theatre as a dialectical tool to make audiences 'dialogue' with the social and to intervene in society and be able to effect change.

-

This brings us to the further question of how bodies are connected to the performance and by implication to the wider theme of embodiment and globalisation. Rio Otomo has reflected on narratives and the body in the Tokyo Olympics.

The body in action generally evokes story-telling in viewers. The initial story, the body-text authored by the actor, is a private and unique inscription on his or her body. This body-text is, however, often overlayed by other narratives to generate different meanings. The relationships between such narratives are unsettling, giving evidence to each other while approaching different ends.[16]

-

This statement is helpful in showing what happens to bodies in the performing arts. Embodiment is a source of dramatic action in the sense that actors are corporeal and mimetically make the drama. Bodies are indexical signs conveying aspects of character, interpersonal relationships, subtext and socio-political contexts. The use of bodies is complicated in 'Tokyo/Olympics' by the active role of the audience as embodied agents in the narrative of the bus tour. A demonstration of how body-texts are 'overlayed' is evident in the subject matter of the Olympics, itself an elite and highly visible display of bodies. In 'Tokyo/Olympics' the corporeal politics of the Games is doubled with the dramaturgical premise of the audience becoming actors. People joining the tour are organised like athletes in a marathon running through the city.

-

Being transported around the city we are invited to read the experience in Michel de Certeau's terms as a 'lexicon' referencing our spatial relations and the regulations that are visible in consequence of the city's capitalist architecture.[17] 'Tokyo/Olympics' is—to use another term from de Certeau—a kind of 'tactical media' in the sense that media is a measure of the everyday and an interventionist pathway in the performance. To remap the city constitutes a radical experience of nomadism wherein, according to Hardt and Negri: 'Mobility and mass worker nomadism always express a refusal and a search for liberation.'[18] In fact, Takayama uses the term 'media' to describe the various elements of the performance such as the bus tour and games centres in this way. Such media, he argues, have many socio-political references and interrupt our expectations of theatre and the city: 'Relating theatre to site specificity,' he argues, should be 'understood not only in terms of spatial interests, but also in the historical context of the site as genre or media.'[19]

Walking the city: from way back when

-

This point is highlighted at the very beginning of the performance. Audience members joining the tour met at Jizō-dōri, a street in Sugamo district in the working class areas that span North-East Tokyo. Jizō-dōri is known for its traditional food shops and for the Kōganji (Kōgan Temple). People have reportedly gathered at this site for ceremonial events since the early 1500s and the place retains a kind of old world atmosphere.[20] It was also the site of Port B's 'Einbahnstrasse' (One-way Street, performed one year earlier in 2006 and the first of Port B's tour performances).[21] Named after Benjamin's multi-layered text,[22] 'Einbahnstrasse' was a site-specific performance that invited the audience to wander the old neighbourhood while listening to oral history narratives on MP 3 players. Jizō-dōri is especially popular among older working class women and is known colloquially as 'old-women's Harajuku.'[23] Drawn by cheaper prices and a familiar Shōwa (1926—1989) era ambiance, older people often pray at the temple where a popular deity (Arai Kannon) offers comfort to those in ill health. This was a symbolic place of departure for the 'Tokyo/Olympics' tour. A location that displayed its preserved 'authentic' Olympics era buildings and atmosphere, it is also a place steeped in a kind of melancholic nostalgia; a place populated by old bent-over women, phantasmic temple deities and ghostly memories of old Edo. With so many older people around, Jizō-dōri makes visible the fact of Japan's aging society (one study estimates that 32 percent of the population will be over 65 by 2050).[24] Perhaps the setting also suggests a more distanced temporal perspective of reflection, as when one visits places like Sugamo to remember the past and look back on one's long life. Sugamo is shown as a resiliently hybrid place, one that mimetically figures as a kind of border crossing. It is a bridge between the old people and the young members of Port B. It spans identifying features of the rural and urban landscape and poses questions about the meaning of 'real' and 'staged' aspects of the tour. It triggers conversations about now and about what lies in the past.

On the tour bus, digging the city

-

As one of the thirty or so people attending the performance—numbers were limited by the number of seats in the bus—I was issued with an MP 3 player and stopwatch and told to wander the neighbourhood and gather at the temple when my stopwatch beeped. Just like any other tour party we where then rounded up onto a yellow Hato Bus by a smartly dressed tour guide complete with waving flag (played here by actor Takayama Akiko, see Figure 2). During the performance, which navigated the vast Tokyo cityscape via the elevated Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway that was originally built for the Olympic Games, tour guiding, commentary and audio interventions were provided by members of Port B and regular Hato bus tour guides. Even the bus driver was asked to reflect on his experience of driving Hato buses through the snarled Tokyo traffic. Oikawa Mitsuyo, a Hato Bus guide from the 1964 Olympics era and now in her seventies, joined the tour as a special guest. Oikawa is a popular figure among many of Tokyo's older residents who nostalgically remember the Olympics era. However, 'Tokyo/Olympics' was no nostalgic act of memorialisation, even though we were introduced to various 'sites' from past decades and a politics of nostalgia was certainly factored into the dramaturgy of this hybrid performance work. Rather, the tour aimed to dissect images, sensations and experiences from the 'high times' of the 1960s and reconnect them with the present globalised cityscape of wider Tokyo. 'Tokyo/Olympics' immersed our bodies in 'digging the past': Benjamin's awareness of history being 'like someone digging' is brought into the present through the audience's sense of rediscovering places and stories amidst the often frenetic pace of modern day Tokyo life. Port B, like Benjamin, looks to the past so as to better understand the present day and future. As Peter Szondi writes: 'Benjamin's tense is not the perfect, but the future perfect in the fullness of paradox: being future and past at the same time.'[25] Seen from this perspective, history looks both ways.[26] Digging suggests an archaeological perspective that sees history in terms of sedimentary layers, fragmentary shards and broken narrative threads; in other words, a history that tells us about continuities and interruptions leading us to an understanding (imperfect and dialectic) about the constituent features of present day society and culture.

Figure 2. Port B actor Takayama Akiko performing the tour guide. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 2. Port B actor Takayama Akiko performing the tour guide. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

|

-

The image of digging is also intensely physical. Oikawa's aging body was highlighted in the marathon-like endurance of her performance. Audiences experienced duration and mobility as a corporeal experience. In 'Tokyo/Olympics,' we traversed vast substrata of Tokyo on a journey that seemed to be taking us to places where memories of the past and the archaeology of the present might be found in a kind of dialogue about the city then and now. It was a dialogue, though, that needed to be cracked open through our participation, through the idea of direct experience. Bodies are implicated in a direct uncovering of the materials and detritus of the past.

-

As noted previously, participatory performance art blurs distinctions between the categories of audience/actor and performance and the everyday, something that Port B call 'trans-border' actions.[27] Newspaper and magazine critics observed in reviews how members of the audience have 'roles' alongside the actors and tour guides.[28] People from everyday Tokyo life also contribute to the performance narrative by their presence, stories and actions. In some scenes, such as the Game Centre and Go Parlour (discussed below) we watch people going about their daily pastimes. As seen through the proscenium-like windows of the bus and at closer hand in the oral history walking tours, the city plays its role as a theatrum mundi, displaying its layers of urban development and brilliant architectural design. Our bodies, and the bodies that make up Tokyo's energised mass are all present here as material for the performance.

Scenes from 'Tokyo/Olympics'

-

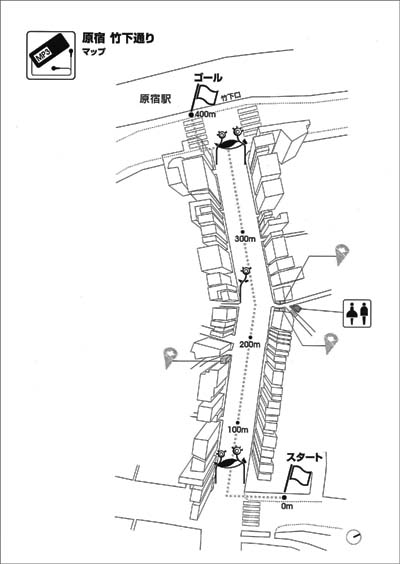

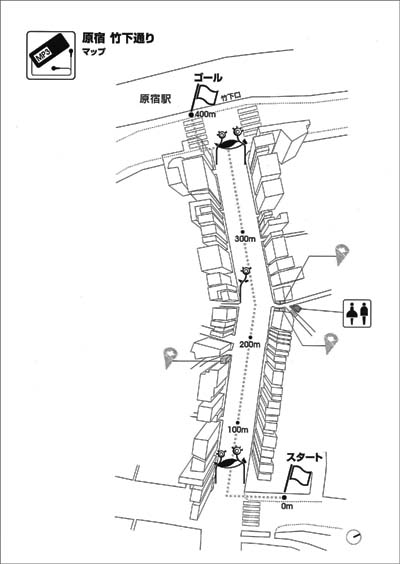

A table in Jizō-dōri was the box office for 'Tokyo/Olympics.' Once on the bus, the audience travelled to Harajuku and walked the length of the famous youth fashion street Takeshita-dōri (see Figure 3). While walking, we listened to interviews with some of the up to 500 touts (many of them illegal workers) who work the strip, trying to attract young women to enter shops and other less savoury activities. It was surprising to learn that people still lived amidst the cheap fashion bazaars and sickly sweet crêpe shops. They voiced their concerns about security and some suggested the need for more street surveillance.

Figure 3. Takeshita Dori Map issued to audience, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 3. Takeshita Dori Map issued to audience, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

|

-

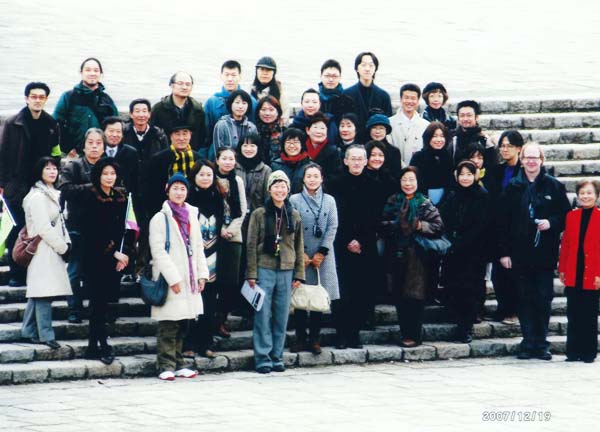

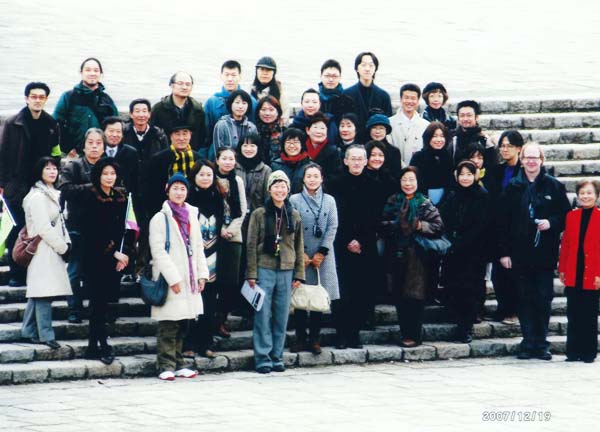

Gathering in front of Yoyogi National Stadium, an iconic Olympic site designed by Tange Kenzō (1913—2005), the audience had the first of several commemorative photographs taken by a roving photographer with a telephoto lens who communicated via walkie-talkie and photographed us from a distant overpass (see Figure 4). Oikawa demonstrated how tour guides were trained to stand and present to audiences: one foot strategically placed, tucked behind and at 45 degrees to the other, a ballet position emphasising decorum and idealised femininity (see Figure 5). She had earlier

Figure 5. The experienced tour guide Oikawa Mitsuo instructs actor Takayama Akiko in the correct physical stance for guiding. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 5. The experienced tour guide Oikawa Mitsuo instructs actor Takayama Akiko in the correct physical stance for guiding. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

| |

recounted how being a tour guide in the 1960s was a sought-after job for women and was well paid. Representing the company in public meant that the women held high status and were considered as an executive class of employee. Her speech was a cultural and economic history of tour guiding taking in the prewar experience of an emancipated and educated class of women whose employment as tour guides grew in relation to the rise of leisure industries and travel in Taishō (1912—1926) Japan. Oikawa showed how tour guiding offered a modern role for women that stressed enjoyment and leisure but also valued education and qualities of leadership. This was a performance where women traversed the city and were valued for their oratory skills as much as for their feminine presentation.

|

Figure 4. The tour commemorative photograph. Each participant was given a copy at the end of the tour. Reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 4. The tour commemorative photograph. Each participant was given a copy at the end of the tour. Reproduced with permission from Port B.

|

-

Returning to the bus, the tour passed by the original Olympic Village at Yoyogi Park, then rode the first expressways skirting by and going through a tunnel running under the Imperial Palace. We passed by the gate of Yasukuni Shrine and visited the park housing the Budōkan (martial arts hall), another Olympic venue. The journey was circling the vast Imperial Place grounds, the 'empty centre' of Tokyo that remains closed to the public and inviolate. A link between imperialism and discourses of the Olympic Games was apparent by the clever framing of the tour in this way. With the exception of the visit to the National Gymnasium (where we were photographed with our backs to the venue, making apparent a kind of avoidance strategy), we never engaged directly with Tokyo's well-known Olympic sites such as the main sports arena, sites included as images on the poster for the performance. Instead we always passed near, or travelled under and around venues while various obliquely referenced stories were recounted. This was making a point about visibility. For example, our guide narrated the history of the site for the Olympic Village in Yoyogi Park, explaining how immediately after the war the park had housed a building called the White House that was occupied by the Allied Powers. Japanese people were barred entry to one of the few open spaces in a city of rubble. Meanwhile, driving by the park in the bus, I was reminded of the small city of homeless people living in cardboard shelters that has taken over one corner of the park since the 1990s. It was becoming clear that the performance was choreographing our experience of space with the aim of recovering alternate histories of these places and sometimes inventing new ones. An official narrative of the Olympics, in this instance to do with the utopian ideal of the international village, was bookended by two dystopic ones: a buried early postwar memory of occupation, and the shanty-town and broken bodies of people in the post-bubble economic crisis.

-

In fact, the Tokyo Games have long been the subject of complicated acts of memory. Best known in this regard is the film 'Tokyo Olympiad' (1965) directed by Ichikawa Kon and commissioned by the Japan Olympic Committee, the statutory authority responsible for organising and running the Games. Ichikawa's documentary film is considered a masterwork by film scholars: using 164 camera operators, cinemascope and high speed film techniques it captured the visceral intensity of athletic bodies and sporting feats of endurance in visionary cinematic form. Although 'Tokyo Olympiad' was popular with audiences, it was severely criticised by government and Olympic officials who believed that the film did not present the 'true record' of a successful games. Kōno Ichirō, Minister for the Olympics, criticised the film as 'inappropriate to leave as a record for future generations' and subsequently had the film withdrawn from a planned widespread public distribution through schools and local government.'[29] Kōno protested that much of Ichikawa's film focused on bodies and movement to the extent that athletes are often not identified, nor is their nationality seen. The film is indeed remarkable in this sense. Repetitious patterns of running and jumping and sequences of limbs extending into space and connecting or propelling sporting apparatus breaks the cinematic unity of the body as a heroic Olympic sign. Instead, these moments of intense physical concentration sometimes appear grotesque, even painful and are radically abstracted, almost disembodied. Kōno suggested that the directorial approach was 'too artistic,' that the film was neglectful in not showing off Tokyo's transformation and the Olympic venues. Put another way, in the film, as with Port B's performance, consideration of the actual places of the Games was deflected so that other questions and concerns might be addressed. Ichikawa's approach has been interpreted as 'humanistic' and focusing on the 'drama of sport.'[30] Most helpful though in adding to the present discussion is Eric Cazdyn's commentary on the film as producing 'a cinematic language to come to terms with the historical situation.'[31]

-

In light of this, a further scene from 'Tokyo/Olympics' is important to consider. While driving alongside the Imperial Palace Moat on the original 1964 expressway, Oikawa told the story of the Japanese Marathon Runner Tsuburaya Kōkichi who took a bronze medal in the 1964 Games. Tsuburaya was running second as he arrived in the stadium to a cheering public and did not hear another runner coming from behind to overtake him. Reportedly, Tsuburaya had been taught as a child to never look back, always only forward to achieve his goals. Four years later, after promising to win a gold medal in the 1968 Mexico Games and losing heart, Tsuburaya committed suicide. His final letter thanked his parents and seemed to apologise for his failing vision of Japanese masculinity. Oikawa recalled that Tsuburaya was praised by nationalistic writers including Kawabata Yasunari and especially Mishima Yukio. Tsuburaya was one of the best known and most remembered figures from the 1964 Olympic Games.[32] A link between the idea of failing the nation on the athletic field and the wartime ideology of sacrificing one's life for the Japanese Emperor was implied. In fact, as Otomo has argued, such an anachronistic nationalist stance was more than implied. She notes how Mishima had a deep and public fascination for the Games; equating sporting prowess with a martial sense of masculinity. This view, a conflation of his romance with the corporeal majesty of sport and war, was one Mishima subtly expressed in his comments as a special media commentator for some of the Olympic events in 1964.[33]

-

The almost proto-fascist theme was reinforced as the bus travelled on to the Budōkan, a large pavilion built to house the Judō competitions and other fighting sports with strong connections to the idea of a warlike fighting spirit. Again, we never saw the actual building; on one trip we were told that there was a concert at the venue and the road was blocked; the second time the bus was unable to park. As we took a toilet break in another area of the parklands housing the Olympics complex it occurred to me that we were left with the possibility to only imagine these venues and their 'heroic' place in the cultural narrative of the Olympics. A kind of phantasmic architecture arising from these unstable viewpoints was being created in these episodes. By decoupling these famous Olympic sites from a performance promising a Tokyo Olympics tour, the performance developed instead a kind of dramaturgy of vanishing.[34] The audience was made to think about other readings of the events of the 1960s. The continual skirting around—driving beside and under—the geography of the authorised 1960s historical landscape in the physical travels on the tour was mirrored in a kind of thinking around the edges of history. Such a clever unity of form and content in the performance was directed towards the creative realisation of a view of history strategically and ineluctably drawn from the margins.

-

This perspective was extended when the tour moved away from referencing Olympics venues directly and became an event reflecting on the city in transition; during the Olympics and before and afterwards. We moved to a 'secret zone' in Ueno. Near the Keisei Ueno Railway Station, in a crumbling building at the edge of Ueno Park, we visited an upper floor Go parlour.[35] As the old men and women played this tactile game of strategy, the air was filled with the sound of scrapping Go stones. The Port B photographer had been travelling alongside the bus on various forms of public transport and reported in by radio asking us to stand by the windows of the building. In a precisely

Figure 6. The tour participants lined up at the window of the Go parlour. Each participant was given a copy of the photograph at the end of the tour. Collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 6. The tour participants lined up at the window of the Go parlour. Each participant was given a copy of the photograph at the end of the tour. Collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

| |

timed manoeuvre, he snapped a photo of the tour party as he passed by riding on a train (see Figure 6). In a melancholic gesture, I was told six months later that the Go parlour had gone and the building was to be demolished. This experience came to be uncanny and gained a stronger sense of politics as a result of the memory of having visited there. A 'secret place' for arcane pastimes had gone; where would the old people go now? Ueno had a history as a black market town in the period after World War Two and then a market bazaar rapidly replaced by chain stores and coffee shops. These are franchises replicating a facile modernity and have no history, no distinctive character, none of the authenticity that comes with age.

|

-

Issued with Japan Railway (JR) tickets, the tour travelled two stops to Akihabara, a major centre of electronics stores and gaming/comic subcultures, and entered a busy gaming centre. We could barely hear the MP3 commentaries by gamers but the intense noise and the hyper-stimulation of the games centre made a strong impression (see Figure 7). Returning once more to the bus, we travelled over the Rainbow Bridge to Tokyo's 1990s postmodern space, Odaiba. Much later, passing by Sunshine City in Ikebukuro after riding the expressway, the commentary recalled the past history of that site as Sugamo Prison. Listeners were reminded that 60 prisoners, including seven Class A war criminals had been executed here after World War Two.[36] Finally, the tour arrived at the Nishi-Sugamo Arts Factory for debriefing and discussion.

Figure 7. Akihabara Games Centre. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 7. Akihabara Games Centre. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

|

'Tokyo/Olympics,' Yasukuni and nationalism: circularity and globalisation

-

Comments cited earlier about Ichikawa Kon's film of the Olympics attempting to express a language to deal with the historical situation apply in particular to an episode linking ideas of sport and event, the city, nationalism and globalisation. To set the scene: soon after leaving behind the commemorative Olympic sites, the bus turned a corner and, suddenly framed by its front windscreen like a proscenium, was the main gate to Yasukuni Shrine (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Yasukuni Shrine. Photo: Peter Eckersall, July 2008.

Figure 8. Yasukuni Shrine. Photo: Peter Eckersall, July 2008.

|

-

As we drove towards the shrine, we heard a text read by a young woman, invisible, standing somewhere on the street and broadcast into the bus PA system. With repetitious phrasing and honorific cadences, the text was almost a prayer. To quote a small section:

Now here it comes! Here it comes! Here comes our glorious Hato Bus. The yellow bus with the mark of a dove (the symbol of peace), our Hato Bus is arriving. What a beautiful yellow. How brilliant it is. Our Hato Bus glides forward. It's like a dream; a moment in a dream…Our Hato Bus fights the good fight and is victorious. Victory! Do your best. Keep it up. Keep it up, Hato Bus.

The 1938 National General Mobilization Law forbid all sightseeing bus tours as extravagant wasteful activities in a time of war. After World War Two, Hato Bus started again. In those days, all vehicles and fuels were under the control of GHQ/SCAP (General Headquarters/Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers). Looking to the future, Hato Bus was running forward: running through the ruins of war, running through the 1950's economic boom, running through the Korean War. Beating all competitors in the sightseeing boom. Running at the Tokyo/Olympics. And still Hato Bus keeps on running…Keep up the good work. Keep it up! Victorious Hato Bus. Keep going, Hato Bus…Our Hato Bus is now approaching the gateway to Yasukuni Shrine. Running straight forward to the huge gate. Heading forward, moving always forward. Named after the symbol of peace, safety and speed, our Hato Bus is moving peacefully…The pace is constant, gentle, steady. Please, take a look at our Hato Bus running on the vast race track called Tokyo.[37]

-

This remarkable text offers a vibrant scenic description of Tokyo's 'high times'—the city reconstructed and moving forward, running away from its past, the city as a vast race track where memories of war and suffering are smoothed over by the iconic marks of peace and prosperity. 'Victorious Hato Bus': Japan requires you to fight. The circularity of the text and repeating moments of performance strive to break into our minds here. It sets a kind of ideological patterning into the experience of navigating the city. It links our embodied experiences of mobility as touring with other kinds of body: athletic bodies and the dead soldiers that stand for the glorious nation.

-

Yasukuni Shrine is mired in controversy and is often linked to nationalist politics and forms of historical revisionism. Official statements about the shrine tend to be benign, identifying Yasukuni with ideas of sacrifice, rebirth and peace:

Yasukuni Shrine was established to commemorate and honor the achievement of those who dedicated their precious life for their country. The name 'Yasukuni,' given by the Emperor Meiji represents wishes for preserving peace for the nation.[38]

-

On the other hand, many protest groups, including Japanese anti-war groups and protesters from former Japanese colonies, reject Yasukuni's benign self-image. These groups point to the shrine's association with Emperor worship and argue that Yasukuni perpetuates a militarist ethic. Visits to the shrine by conservative Japanese Prime Ministers (superficially as private citizens) raise the ire of people in China and Korea who consider these visits insensitive in seeming to honour Japan's colonial history in Asia. People also complain that their dead relatives have been interred at the shrine without their permission.[39] In associating so completely with mythical nationalist perspectives on Japan's wartime record, Yasukuni aims to perform a virtuous martial historical narrative. However, by placing the shrine in juxtaposition with commemorative sites for the 1964 Olympics and alongside the gritty history of the Hato Bus Company a new awareness of cultural patterning emerges. War and sport are metaphors for capitalism: be it colonial expansion or globalisation—get it up, keep going, onward, or exhaustion and death.

-

In light of this, the revival of nationalist politics in an era of globalisation is given context. Globalisation has hollowed out older forms of industrial capacity and Japan, like elsewhere, has experienced increased levels of insecurity and unemployment. In fact, conservative governments favouring neo-liberalism also pander to local national sentiments in a tricky power balance. The call to unity is made in the hope that the fragmentation of communities can be countered. Thus, while Yasukuni is a complex site for historical analysis, one can also see how national political figures use Yasukuni in the service of a nationalist agenda in the wider context of globalisation.

Collapsing space

-

Ōtori Hidenaga shifts this analysis onto a wider stage, describing these scenes as a form of 'living geography'; a performance that activates a geopolitical awareness of space. He notes that in the virtualised informational economies of advanced capitalist societies, space as sign of distance, of an experience of temporality, has collapsed. Distance, he notes, is meaningless in computer terms; space relates to data storage capacity and not to a physical landscape.[40] Ōtori identifies the consequent homogenisation of culture in a digital spatial paradigm of flatness. We can see this idea expressed in the coda to 'Tokyo/Olympics.'

-

After returning to Port B's office space at the Sugamo Arts Factory we were offered coffee and snacks and invited to discuss the performance. Dominating the space though was a projection of the tour in graphic form, a perspective that replicated the image style of a car satellite navigation system. This was a recording of the journey of our tour constantly replayed as a data-loop. As per the image retracing the route in graphic detail, our experience of traversing the city was one that was both flattened and made infinite. Far from being an embodied, haptic journey, the performance concluded as a virtual re-enactment. As we had been thinking about history and had been physically immersed in experiences of cultural memory, this transformation suggested precisely how space and time were collapsed into digital ephemera using the tools of global technology.

-

Zygmunt Bauman's writing on globalisation is helpful to understanding how Port B explores these issues in their performance. He writes that in a globalised world: 'information now floats independently from its carriers; shifting of bodies and rearrangements of bodies in physical space is less than ever necessary to reorder meanings and relationships.'[41] While this is indeed an apt description of Port B's postmodern geography, it can also be seen that the company 'rearranges' space and bodies not to lose perspective but to rekindle resistance to history's collapse into postmodern flows. To this end, 'Tokyo/Olympics' figures our sense of temporality to give a sense of the past sitting alongside and in immediate contrast with the globalising present-day world. By placing bodies into local spaces and emphasising the contrast between the global postmodern city and the broken fragments of a city living in the past, 'Tokyo/Olympics' works against the inevitability of a globalising flattening out of history and culture. Rather than the tendency towards a floating, ambient form of globalisation as described by Bauman, in these fragments Takayama sees more active interference: 'I don't like it when everybody heads in the same direction and I actually think it's a rather bad thing.'[42]

-

In other words, 'Tokyo/Olympics' explored the dilemma of 'being there' in place and time, in the past and present, as an archive of living in the global city. By comparing Japan's 'high times' with aspects of the contemporary globalised city, 'Tokyo/Olympics' can be read as a corporeal recuperation of the disconnected threads of history. This was Ōtori's point about homogenisation, a point also evident in relation to the scene in the Go parlour above. In 'Tokyo/Olympics', place and time become simultaneously more blended and yet, perhaps contradictorily, more interrupted. Something other to what one normally expects is produced from this cracking open of history. Small moments, glossed over by the intensity of global capitalism, are seen again. Sometimes beautiful, sometimes anachronistic, the point is not to measure everything, but to make it visible to the imagination.

Closing: 'Over there…if you know where to look'

-

'Tokyo/Olympics' can be understood as a work to resist and particularise our daily experiences of globalisation. It revives and energises our capacities to navigate and experience place, both in the sense of being somewhere and having history. It is a dramaturgy of fragments and vanishing; like Benjamin's Arcades project from which it takes inspiration, the performance explores places and experiences of remembering.[43] Confusingly, this is not a stable experience but a multilateral and imaginative exploration of co-locations and synthesis. We walk through, meet with, dig to recuperate the past, just as we are watched and become a part of that process. In 'Tokyo/Olympics' it was sometimes unclear who was performing and what was being performed. What was always clear was the intentional and self-conscious experience of what Benjamin calls 'immersion in the most minute details of…material content.'[44]

-

This becomes clear in a final informative scene from 'Tokyo/Olympics': the bus travels far out over Tokyo Bay on one of the newer elevated express roads. We pause in a desolate place for a toilet stop where the only sign of life is a coin drink machine. We are surrounded by the global Tokyo cityscape: all electric shapes in the fading daylight. Now fully transfixed by the wealth and aesthetics of global capitalism, the individual components of the city—so recently visited and dissected—have been erased by the East Asian cyber aesthetic overflow. Why are we here, I wonder, in this windswept island in the middle of the superhighway; in a space that is more non-space as theorised by Marc Augé.[45] Later, Takayama explains: the rest stop looked over Tokyo Bay across to Yume no Shima (Dream Island), ironically, an island made of Tokyo city refuse and a 'dream' project of the former Tokyo Governor Suzuki Shun'ichi. 'Over there (if one knows where to look) one can see the place that would have been the site for the 1940 Tokyo Olympic games—cancelled because of the war'.[46] A site banished as an unwelcome memory of military dystopia but reborn in the high times of 1964 is phantasmically reanimated here in December 2007. Moreover, history repeats: the controversial Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintarō announced in 2007 a bid to host the 2016 Olympic Games and the subsequent need to mobilise the energies of the city once more.[47]

-

In this article I have argued that 'Tokyo/Olympics' was not so much about the memory of the past, but the vantage of forgetting. The tour made visible how events like the Olympics gave a sense of permission to citizens to leave the past behind, to forget unresolved questions about the war, about responsibility and about Japan's manner and details of postwar reconstruction, about how the future of society might be addressed. 'Tokyo/Olympics' invited participants to remember analytically, critically, but also fondly the utopian idea of the 1960s. As layers of place, time and narrative unfolded, an idea of corporeality worked metaphorically to show a city as haptic nodals, the fleshy, interconnecting tissue of place and experience. By making this a tour performance the body is activated and implicated in this journey. As Takayama notes, 'Through the experience of a work of art, you can create new ways of looking at the world. Your view (can be changed).'[48]

Endnotes

[1] Walter Benjamin, Archives, London: Verso, 2007, p. ii.

[2] Tadashi Uchino, 'Globality's children: the "child's" body as a strategy of flatness in performance,' in The Drama Review, vol. 50, no. 1, Spring (2006):57–66, p. 58.

[3] The 2008 Beijing Olympics Games makes reference to the games being held in Asia for the first time in 1964. The official Beijing 2008 website includes an image from the rehearsal for the 1964 torch lighting ceremony. See 'Yoshinori Sakai holds the Torch,' (5 October 1964) in Light the passion; share the dream: Beijing 2008, 2008, online: http://torchrelay.beijing2008.cn/en/archives/modern/1964/headlines/n214033902.shtml, site accessed 24 November 2008.

[4] For example, Yoshiko Nozaki, War Memory, Nationalism and Education in Post-War Japan, 1945–2007: The Japanese History Textbook Controversy and Ienaga Saburo's Court Challenges, London and New York: Routledge, 2008.

[5] Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995; Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism or the Logic of Late Capitalism, Durham: Duke University Press, 1991; Fredric Jameson and Masao Miyoshi (eds.), The Cultures of Globalization, Durham: Duke University Press, 1998.

[6] Peter Eckersall, 'Twentieth Century Enjoyment Plaza: Private Space and Contemporary Art in Mori's World,' in Performing Japan: Contemporary Expressions of Cultural Identity, ed. Henry Johnson and Jerry Jaffe, Kent: Global Oriental, 2008, pp. 156–71.

[7] Marvin Carlson, Performance: A Critical Introduction, London and New York: Routledge, 1996, p. 6.

[8] Dwight Conquergood, 'Performance studies: interventions and radical research,' in The Drama Review, vol. 46, no. 2 (2002):145–56, p. 145.

[9] Tatsuki Hayashi, 'Leaving the theatre to find an audience—notes on the dramaturgy of "Tokyo/Olympics",' unpublished conference paper, Performance Studies International, University of Copenhagen, August 2008, unpaginated.

[10] Baz Kershaw, The Radical in Performance: Between Brecht and Baudrillard, London and New York: Routledge, 1999, p. 183.

[11] Hayashi, 'Leaving the theatre to find an audience.'

[12] Maurice Roche, Mega-Events and Modernity: Olympics and Expos and the Growth of Global Culture, London and New York: Routledge, 2000, p. 25.

[13] Tony Schirato and Jen Web, Understanding Globalisation, London: Sage, 2003, pp. 33–34.

[14] Akira Takayama, expressing his interest in applying a model of didactic theatre as proposed by Bertolt Brecht. See 'On the creation of "Tokyo/Olympics",' unpublished conference paper, Performance Studies International, University of Copenhagen, August 2008, unpaginated.

[15] Takayama, 'On the creation of "Tokyo/Olympics".'

[16] Rio Otomo, 'Narratives, the body and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics,' in Asian Studies Review, vol. 31, no. 2, July (2007):117–32, p. 117.

[17] See Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, London: Routledge, 1984.

[18] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2000, p. 212.

[19] Takayama, 'On the creation of "Tokyo/Olympics".'

[20] Sumiko Enbutsu, 'History still alive in the old Nakasendo: a stroll through Sugamo Koshinzuka reveals remnants of its rural past,' in The Japan Times (August 15 2002), online: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fe20020815se.html, site accessed 21 November 2008.

[21] See the Port B website for summaries of their works to date including 'One Way Street.' See online: http://portb.net/eng/index.html, see archives, site accessed 21 November 2008.

[22] Walter Benjamin, One-way Street, and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter, London: NLB, 1979.

[23] (Obaasan Harajuku). The famous youth shopping district Harajuku probably does not require an introduction to readers. On the weekends especially, vast numbers of young women, teenagers in the main, gather to shop and view the latest fashions.

[24] André Sorensen, The Making of Urban: Cities and planning from Edo to the Twenty-first Century, London: Routledge, 2002, p. 354.

[25] Peter Szondi, 'Hope in the past: on Walter Benjamin,' trans. Harvey Mendelsohn, in Critical Inquiry, vol. 4, no. 3, Spring (1978):491–506, see p. 449.

[26] A connection to Benjamin's idea of the 'Angel of History' is also suggested; a point noted by Shintaro Fujii, in 'Dramaturgies outside the frame-discovering the city in "Tokyo/Olympics",' unpublished conference paper, Performance Studies International, University of Copenhagen, August 2008, unpaginated.

[27] Port B company website, online: http://portb.net/, site accessed 21 November 2008.

[28] See Nobuko Tanaka, 'Akira Takayama's "Tokyo/Olympic": a drama of our own making,' in The Japan Times, 16 December 2007, online: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20071216x3.html, site accessed 21 November 2008; Tetsuya Ozaki, 'Out of Tokyo: the city as a stage,' in Real Tokyo, column no. 176, 1 December 2007, online: http://www.realtokyo.co.jp/docs/en/column/outoftokyo/bn/ozaki_176_en/, site accessed 21 November 2008.

[29] Cited in Mark Normes, in 'Tokyo Olympiad: a symposium,' in Kon Ichikawa, ed. James Quant, Toronto: Cinematheque Ontario Monographs No 4, 2001, pp. 315–37, 319.

[30] James Quant, in 'Tokyo Olympiad: a symposium,' p. 318.

[31] Eric Cazdyn, in 'Tokyo Olympiad: a symposium,' p. 333.

[32] Fujii, 'Dramaturgies outside the frame.'

[33] Otomo, 'Narratives, the Body and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics,' p. 119.

[34] See: Ivy, Discourses, 1996, pp. 9–13. Her book 'traces remainders of modernity within contemporary Japan,' p. 9.

[35] Go is a board game played extensively in China and Japan and is sometimes compared to chequers. Opposing players move black and white stones (ishi) on a grid-like board with the aim of encircling and capturing an opponent's stones.

***

[36] In early 2008, Port B made a third tour performance that explored a cultural history of the Sunshine City tower. See online: http://portb.net/eng/arch_frame.html?sunshine/sun_home.html, site accessed 26 November 2008.

[37] 'Tokyo/Olympics' performance text, unpublished manuscript, translated by Makiko Yamanashi and Peter Eckersall.

[38] 'About Yasukuni Shrine,' in Yasukuni Shrine, 2008, online: http://www.yasukuni.or.jp/english/about/index.html, site accessed 24 November 2008.

[39] See Yasukuni (a documentary film about Yasukuni's political controversy), director Li Ling, Dragon Films, 2007.

[40] Hidenaga Ōtori, 'An experimental performance to recall history and geography,' in Theatre Arts, May (2008):124–32, p. 125.

[41] Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998, p. 18.

[42] Takayama cited in Ozaki Tetsuya, 'Out of Tokyo: The City as a Stage.'

[43] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1999.

[44] Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne, London: Verso, 1998, p. 29

[45] Marc Augé, Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, London: Verso, 1995.

[46] Takayama, interview with author, Tokyo, 18 December 2007.

[47] See Tokyo 2016: Candidate City, (C)2007–2009, online: http://www.tokyo2016.or.jp/, site accessed 24 November 2008.

[48] Akira Takayama, interview with author, Tokyo, 18 December 2007.

|

Figure 1. 'Tokyo/Olympics' poster, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 1. 'Tokyo/Olympics' poster, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 2. Port B actor Takayama Akiko performing the tour guide. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 2. Port B actor Takayama Akiko performing the tour guide. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 3. Takeshita Dori Map issued to audience, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 3. Takeshita Dori Map issued to audience, collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 5. The experienced tour guide Oikawa Mitsuo instructs actor Takayama Akiko in the correct physical stance for guiding. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 5. The experienced tour guide Oikawa Mitsuo instructs actor Takayama Akiko in the correct physical stance for guiding. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 4. The tour commemorative photograph. Each participant was given a copy at the end of the tour. Reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 4. The tour commemorative photograph. Each participant was given a copy at the end of the tour. Reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 6. The tour participants lined up at the window of the Go parlour. Each participant was given a copy of the photograph at the end of the tour. Collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 6. The tour participants lined up at the window of the Go parlour. Each participant was given a copy of the photograph at the end of the tour. Collection of the author, reproduced with permission from Port B.

Figure 7. Akihabara Games Centre. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 7. Akihabara Games Centre. Photo: Peter Eckersall, December 2007.

Figure 8. Yasukuni Shrine. Photo: Peter Eckersall, July 2008.

Figure 8. Yasukuni Shrine. Photo: Peter Eckersall, July 2008.