Western Inscriptions on Indonesian Bodies:

Representations of Adolescents

in Indonesian Female Teen Magazines[*]

Suzie Handajani

Introduction

-

My interest in Indonesian female teen magazines was sparked by the fact that there has been a rapid development in publishing due to freedom of press in Indonesia since the end of Soeharto?s rule in 1998. The development of private television stations in Indonesia has accelerated tremendously since the end of the New Order.[1] The proliferation of private television stations intensified the development of other forms of media, particularly entertainment magazines and tabloids, because more television stations means more celebrities to feature in the entertainment print media.[2]

-

A very high proportion of teen magazines in Indonesia are for girls. In this article the discussion is limited to three Indonesian female teen magazines, based on their popularity at the time: Gadis [Young Girl], Aneka Yess! [Variety], and Kawanku [My Friend]. They were collected randomly during 2002 and 2003. Nevertheless, I think the result is still in line with current trends in Indonesian female teen magazines. Most researchers on female magazines will find that this type of media does not change drastically over time despite differences in research period. These female magazines always show a preference for, and idolise certain types of female representation.[3]

-

In this article I show how girls? magazines perform seemingly contradictory dual roles: the dissemination of modernity and the preservation of tradition. The paradoxical nature of the magazines mirrors the paradoxical nature of young girls as constructed by society. Suzanne Brenner argues that females often bear the burden as indicators of modernity. She observes ?that images of women more than men have been used to signify the transition from tradition to modernity, and that this has its own significance in the Indonesian context.?[4]

-

However, at the same time representations of the girls in the magazines have to show respect to local tradition as the norms of morality. This social attitude is summed up by Judith Williamson, who contends that

Women, the guardians of 'personal life,' become a kind of dumping ground for all the values society wants off its back but must be perceived to cherish: a function rather like a zoo, or nature reserve, whereby a culture can proudly proclaim its inclusion of precisely what it has excluded [original emphasis].[5]

-

I argue that the construction of the west in these magazines is used to fulfil the aims of the magazines to advertise modernity and conserve tradition. For this purpose I apply Merry White's argument with regards to marketing to adolescents, to claim that Indonesian female teen magazines have conflicting agendas in representing adolescents.[6] On one hand, these magazines aim to fulfil the commercial interests of marketers in order to achieve financial security by selling modernity. On the other hand, as part of the society in which these magazines are published and circulated, they have to acknowledge local values through their representations of the girls.

-

In this article, I explore to what extent and in what ways western influences are employed to construct representations of female adolescents. I argue that the ways these magazines construct ideals of the 'west' are enmeshed with the ways in which they construct images of Indonesian female adolescents. The constructed images of the Indonesian girls in the teen magazines show them as modern and globalised and westernised. At the same time discourse in the magazines is constructed to view western morality as a threat.

-

To achieve this double agenda the magazines divide the 'imagined' west into good and bad templates. The west is often treated as monolithic and unproblematic, while the heterogeneity of western culture is ignored. Globalisation in the magazines is presented as modernity stemming from the west. In dominant representations found in these magazines, Indonesian culture is commonly subsumed by global western culture. However, it should be noted that sometimes Indonesian-ness is presented as markedly distinct and separate from the west. This occurs when the west becomes the 'bad guys.'

The social background of Indonesian adolescents

-

The term and concept of adolescence (or remaja in Indonesian) is a relatively recent one in Indonesia. In fact, adolescence is a new concept in many countries of the world. In the United States, for example, the concept of adolescence was not popular before the Second World War. Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess and Gloria Jacobs mention that:

Consciousness of the teen years as a life-cycle phase set off between late childhood on the one hand and young adulthood on the other only goes back to the early twentieth century, when the influential psychologist G. Stanley Hall published his mammoth work Adolescence. (The word 'teenager' did not enter mass usage until 1940.)[7]

-

Previously the common understanding was that childhood continued straight to adulthood. Lenore Manderson and Pranee Liamputtong say that, in situations where young men and young women (or girls) enter marriage (or employment) at an early stage in their life, teenhood simply may not exist.[8] However, anthropologists have done research in many societies where adolescence is a period that marks a person's maturation towards adulthood.[9] So there is always an acknowledgement of a certain stage before adulthood, although it may not necessarily be a prolonged separate stage like modern adolescence.

-

Indonesian adolescents are viewed in this article as a social group that has emerged as a result of Indonesia's national development in the twentieth century. Adolescence is discussed here not as a biological state of human physical development often associated with puberty, but as the result of changes in the state's perception and the treatment of young people by society.

-

Over the last century, Indonesian society has created a generation of youth that fits in with its own changing needs. As Louise J. Kaplan argues, 'Every society attempts to preserve itself by inventing the adolescence it requires.'[10] For instance, during the Dutch occupation, Indonesian nationalists needed to recruit all the available human resources to get rid of the Dutch. In the 1920s, at the start of the nationalist movement, young people (mostly males) were enlisted and represented as 'freedom fighters.'[11] Although many were very young and in their teens, the word pemuda [young people] was employed to designate this group rather than remaja [adolescents]. Jean Gelman Taylor refers to the word pemuda as having 'a legacy of violence' which invokes images of revolution and social turmoil.[12] As for young girls, most of them transitioned directly from childhood to adulthood through early marriages. Elsbeth Locher-Scholten mentioned that child marriage was common during the Dutch period among 'the natives' despite cries from educated Indonesians and concerned Dutch people for regulations to prevent it. Girls as young as twelve or thirteen were rushed off into arranged marriages.[13]

-

The concept of Indonesian remaja as teenagers (in place of pemuda) emerged after independence and developed during the New Order (1966–1998) due to several factors. In 1973, the New Order passed a new Marriage Law that, among other things, prevented marriage for females under sixteen and males under nineteen.[14] In 1984, the government launched the six-year compulsory education drive (Wajib Belajar) for elementary school children and, in 1994, the government extended the program into junior high school, making education compulsory for nine years (Wajib Belajar Pendidikan Dasar 9 Tahun) from six to fifteen years of age.[15] By establishing this minimum age for marriage and legislating education nationwide, the New Order helped to create the early breed of remaja or Indonesian adolescents. During the New Order, rapid economic and communications development expanded the Indonesian middle class. This resulted in more middle-to-upper class families sending their children to pursue higher education, which in turn delayed marriage and employment. This coincided with the period that Richard Robison refers to as 'The Rise of Capital'.[16]

-

Ben Anderson summed up the modern definition of Indonesian remaja as follows:

Remaja as a social group are young people, they are not working, but pursuing their education instead. So the change from pemuda to remaja is the result of the spread of the Indonesian education system. Another reason is the emergence of the Indonesian middle class during the New Order. Along with this has also been the emergence of spoilt youngsters whose mums and dads are wealthy, consumerists, etc. [17]

So images of youths full of hardships from the revolution era that emanate from the word pemuda are now replaced with remaja who conjure up images of wealth and the social stability of the New Order.

-

The state demanded political stability and compliance from young people to sustain its power. In education this materialised with centralised curriculum and a top-down teaching system.[18] Saya Shiraishi argues that the concept of remaja in the New Order was produced to counter 'the revolutionary pemuda of 1940s and the students of 1960.'[19] Remaja in the New Order became more visible as a social group but were politically insignificant. One important move by the New Order in this respect was the 'Normalization of Campus Life' [Normalisasi Kehidupan Kampus] which banned university students from engaging in political activities because it was deemed as not 'normal'.[20] This banning was in line with the concept of a 'floating mass' invented by Ali Moertopo who stated that political activities did not need to reach the grass roots level. Political activities should be left to politicians, so the rest of the population (such as students) can concentrate on more important things in life (such as study).[21] Saya Shiraishi maintains that remaja of the New Order are constructed to be 'politically tame.' [22] After the 1998 reform, President B.J. Habibie cancelled the Normalization of Campus Life policy during his presidency, which meant allowing university students to be involved in politics.[23] Nevertheless, despite the legal re-entering of young people into the state's political ring, popular images of Indonesian adolescents as non-political were already well-established.

-

However, in New Order development discourse, the state viewed remaja as the future generation, at the same time adolescents were an expanding mass of consumers as capitalism flourished in this period. The Indonesian state faced a contradiction in assuming the need to protect the young generation from the 'vices' of globalisation, while at the same time realising that adolescents were a profitable target market in a newly capitalised society.[24]

-

Drawing generally from discourses in the media, the state has frequently seen globalisation as a threat to Indonesian adolescents. However, the state construction of globalisation is often limited to cultural westernisation, which could be associated with moral degradation[25] Adolescents are seen as being in danger from the negative influence of globalisation. Popular discourse contends that if the younger generation loses their 'high eastern values' to the 'immoral western values,' the country will be morally colonised. Globalisation is typically perceived of as a menace, with adolescents the most prone to its destructive nature. Therefore, a popular public discourse by Indonesian dignitaries during the New Order often stated that every preventive measure should be taken to 'filter' globalisation so as to make it safe for Indonesian adolescents to adopt and consume.

-

To illustrate, Amien Rais, in his book Moralitas Politik Muhammadiyah [Muhammadiyah Political Morality], has this to say on globalisation in the context of Islam (therefore Indonesia, since Islam is the religion of the majority):

winning Indonesia's adolescents is a long term obligation of Islamic teaching. Our children and adolescents are invaluable assets. We have to save them from the erosion of faith caused by the invasion of un-Islamic values which seep into the heart of various Islamic communities in Indonesia. If our children and adolescents have a strong fortress (al-hususn al hamidiyyah) in this era of globalisation and information, if God is willing, then our future will stay pure.[26]

The word 'fortress' in this quotation is used to depict what is needed in the face of globalisation. Rais sees globalisation both as an invasion and as the bearer of all worldly sins. Therefore a boundary fortifying the 'purity' of young generation should be established.

-

In the mean time, adolescents in Indonesia are growing in number and as a proportion of the total population.[27] Additionally, the connotation of remaja is that they come from the wealthy middle-to-upper class and enjoy a disposable income. In line with the advances in technology and communication, and the globalisation of the media, new products are continuously being invented for teenagers. It is ironic that adolescents, who, according to the state, should be protected from the 'vice' of globalisation, are also increasingly the target of 'global' products. According to Nielsen Media Research in Indonesia, as quoted in the daily newspaper, Kompas, the number of products made for adolescents is increasing more rapidly than the number of products developed for other demographic groups such as adults.[28]

-

One of the products popular among teenagers is magazines. Magazines in general are an important type of media in Indonesia. In a survey done by A.C. Nielsen, magazines came third as the most popular media that attracted advertisers in Indonesia after television and newspapers.[29] As stated in my introduction, the magazines I chose for my research are Gadis, Kawanku and Aneka Yess! because, according to a Nielson survey, these are the teen magazines with the highest readership.[30] When compared with others, these magazines are also the longest running female teen magazines in Indonesia (Gadis was first published in 1973, Kawanku in 1970, and Aneka Yess! in 1992).[31] Apart from these local publications, there are also magazines licensed from America, such as CosmoGirl Indonesia and Seventeen, which were relatively new to the Indonesian market. Both local and licensed magazines cover fashion, celebrities, entertainment, lifestyle and short stories (at the time of research, short stories were only available in local magazines).

-

Given the diversity of Indonesia and the heterogeneity of its adolescents, girls' magazines can be an important source of information about remaja and adolescent peer group concerns. Although real Indonesian remaja do not all look like the ones represented in the magazines (in fact most of them do not), the magazines have the potential to reveal the dominant perceptions of what it means to be remaja in Indonesia. Vicki Shields mentions that 'Text...has the ability to reflect or reproduce dominant cultural discourse.'[32] This suggests that, in the Indonesian context, the magazines deal with idealised and commercialised versions of remaja rather than the reality of heterogeneous Indonesian adolescents.[33] Ros Ballaster, Margaret Beetham, Elizabeth Frazer and Sandra Hebron additionally argue that, 'magazines are part of an economic system as well as part of an ideological system.'[34] The teen magazines I analyse below, show how the global and the local blend and where divergences occur. Although not real, the idealised representations in the magazines give a sense of ideals or standards for Indonesian adolescents to separate the best from the rest. These magazines also provide a sense of community for Indonesian youths and serve as a benchmark to gauge whether or not they belong to a modern social group called remaja.[35]

East meets West

-

I propose to place my discussion in this section of how adolescents are represented in Indonesian female teen magazines within a larger context of global-local interaction at the national level. Carla Jones acknowledges that 'the New Order image of the ideal modern Indonesian woman combined Western ideologies of bourgeois domesticity with local, so-called traditional ideologies of femininity and bureaucratic images of dutiful citizenship.'[36] Therefore this section is divided into two parts. The first part shows how the magazines claim western images as the source of global modernity. In the second part, I analyse how the west is constructed as 'the opposition' in a bid to respect local values.

-

Teen magazines are sites where globalisation meets Indonesian identity. According to Merry White, what the market needs from female teen magazines are homogeneous consumers.[37] A single type of consumer is easier to address than a scattered demographic of adolescents. By providing updates on products and role models, the magazines create a homogeneous group of female teens. The magazines do this, by standardising physical beauty and attitudes.

Selling global modernity

-

In framing my research methodology, I opted for exploration of physical features such as skin, height and eye colour to exemplify how constructed images of the west are embodied by teenagers in the magazines. Some of the examples I use are from advertisements in the magazines, because they are more overt about emulating the west, whereas the magazines' written content is more tacit in promulgating the western look.

-

Compared with other cosmetic products advertised, skin whitening has the widest range of products and brands.[38] Whitening skin products include body lotions, liquid facial cleansers, liquid soaps, sunscreens, moisturisers, toners and body scrubs. Sometimes one brand comes with several skin whitening products (see Figure 1). Both advertisements and editorial content reinforce

|

|

the supremacy of light skin by making dark skin almost absent in text and imagery. This is similar to Dédé Oetomo's comment about the Indonesian media being so full of representations of people with light skin 'except for the drivers, maids and comedians' that the image of whiteness becomes associated with social status.[39] Although not making direct reference in either the advertisements or in the content, to emulating western complexion, white skin is linked with modernity and affluence, which is closely associated with the west. I would like to use Vanita Reddy's term to explain this process as 'naturalising' the beauty of light skin.[40] The magazines make frequent reference to modernity and high social class being 'naturally' associated with light skin. This implicit association is evident in the following quotation from a short story in Aneka Yess!:

Figure 1. An advertisement for skin whitening products in the form of body scrub foam, hand and body lotion, moisturizer, and facial peeling soap. Source: Gadis, no. 24/XXX, 5–15 September 2003, p. 2.

|

Ning has been restless these last few days. It's a week before Valentine, but she's not ready for a stunning appearance at Sisca's party. She feels like she wants to look different on Valentine's day. The dress? No problem. A pink one with laces, bought several days ago, will make her look fashionable. Shoes? Not a problem either. Her biggest problem is her skin that's getting darker because she's been swimming too much. It's just no match with Rio's. Rio's face is so oriental with the clear skin and all. If they walk together people might think that she's the daughter of Rio's servant. How dreadful is that?[41]

In the passage above dark skin evokes the image of a maid's daughter who not only represents lower class status but also hardship and labour. The story implies that with dark skin and its association with lower social status it is impossible to look beautiful.

-

Whiteness is also associated with wealth since the ability to pursue beauty through modern facilities has to be financially viable. In this story, Ning represents wealth and high class status: she observes Valentine's Day through her purchase of a pink evening dress for the occasion. Her acknowledgment of an imported tradition links her with a western image that boosts her status. However, the stigma of being dark is that it is embarrassing and so 'local'. Light skin has the ability to transcend this locality and to pave the way for adolescents, especially the girls, to become members of the 'global' elite.

-

A height enhancing product (Figure 2) is another example of the idolisation of the western physical

Figure 2. An advertisement for a height enhancing product. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 4, 13–26 February 2003, p. 135.

Figure 2. An advertisement for a height enhancing product. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 4, 13–26 February 2003, p. 135.

|

|

ideal.[42] It is worth mentioning here because an ideal height that gives the image of slenderness is frequently represented in teen magazines and not just in advertisements for height enhancing products. This is due not only to the fact that being tall is one of the most coveted western physical traits (in addition to having light skin and blue/green/grey eyes), but also because these magazines feature a lot of modelling activities in which height is a prerequisite for obtaining modelling work, along with a light skin colour and attractiveness. However, having light skin is a tacit prerequisite because it is deemed so 'natural' a prerequisite that it needs no mentioning at all.[43] In another advertisement for a height enhancing product, modelling and other professions such as nursing and being a flight attendant are mentioned as reasons for which a person might wish to increase their natural height.[44] The advertisement in Figure 2 references the 'west' as the source of technology, but does not say that the purpose of gaining height is to look like a westerner. However, the female model for the advertisement has fair skin and brownish hair in addition to her tall figure. This suggests that being tall with white skin and a 'non-native' look is the norm of beauty for Indonesian girls.

|

-

The claim that the product is 'new from the USA' emphasises the need for endorsement from the west. This is what Carla Jones calls 'global referencing'.[45] The advertisement says that the product is, 'A new formula from the USA, which has been proven in Malaysia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and in the country of its origin.' The message that taller is more beautiful seems to blur the logic of the above sentence. Relatively tall Americans (despite the multiculturalism of America, it is clear that the advertisement refers to white Americans who are naturally taller than Indonesians) are posed as living proof that the product really works. Height that produces the effect of slenderness becomes part of an aesthetic package inspired by stereotyped western bodies.

-

Another effort to achieve a 'westernised' look is to wear contact lenses (see Figure 3). A lot of

Figure 3. An advertisement for contact lenses portrays an effort to emulate a western appearance. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 23, 7–20 November 2002. p. 78.

Figure 3. An advertisement for contact lenses portrays an effort to emulate a western appearance. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 23, 7–20 November 2002. p. 78.

|

|

models featured in the magazine articles wear them. Unlike the light skin phenomenon, contact lens advertisements in these magazines explicitly mention the purpose of these products is to create a look as glamorous as 'western' eyes.[46] The following is a quote from an advertisement for contact lenses in Gadis:

'You don't have to be a westerner to have colourful eyes. Just wear contact lenses. Your eyes will become more expressive.[47]

In Kawanku and Aneka Yess! the contact lens advertisements make reference to western celebrities:

[A]ren't you jealous of Kirsten Dunst's clear blue eyes or Britney Spears' brown hazel ones? Throw away your jealousy. We can have brown, blue, or even green eyes. Change your eye colour in seconds. The secret? Soft lenses, of course![48]

Are you often fascinated by Elijah Wood's eyes that are as blue as the sky? It's alright to be fascinated, but you have to know that we can be like them! Just wear contact lenses and match it with the right make up, and you won't be beaten by their looks.[49]

|

-

Compared with the discourse on complexion which 'naturalises' light skin, advertisements for contact lenses use the discourse of empowerment and being the agent of change in manipulating the natural eye colour ('we can be like them!' and 'you won't be beaten'). This way the ability to imitate is given a sense of prestige rather than being 'naturalised.'

-

In the above examples, the discourse on light skin is the most 'naturalised' since there is no allusion to imitating the west. It is the western lifestyle that is referenced instead. In advertisements for height enhancers, credit is given to the 'west' as the source of technology that invents the product but the discourse does not mention being tall as imitative of the west. Contact lens advertisements, by contrast, are the most explicit in expressing that these products will deliver the western look as exemplified by western celebrities.

-

It is through these kinds of representations of feminine beauty that teen magazines play the role of 'cultural supermarkets' by promoting western bodies as the ideal.[50] The magazines' mission to create a homogenised look is achieved by 'nationalising' desired body traits to become an ideal Indonesian look.[51] Figure 4 from a modelling competition is an example of the standardised look for girls. Susan Bordo comments that,

we are surrounded by homogenizing and normalizing images—images whose content is far from arbitrary, but is instead suffused with the dominance of gendered, racial, class and other cultural iconography.[52]

Figure 4. Modelling competition. Standardising the look. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 20, 25 September–9 October 2003, p. 48.

Figure 4. Modelling competition. Standardising the look. Source: Aneka Yess!, no. 20, 25 September–9 October 2003, p. 48.

|

Hailing local tradition

-

In teen magazines images of the west as the 'bad guys' are constructed whenever issues of morality are brought to the fore. While social and physical ideals depicted in the magazines are dominated by constructions of western performance, the standard of morality is governed by constructions of local norms.

-

The magazines do not cover morality as a whole, but tend to choose discourses on sex and sexuality that symbolically indicate that the magazines uphold local morals and values. This serves to counter any public insinuation that adolescents are being brainwashed by the west through the global pop culture they are exposed to in Indonesian teen magazines. To counter potential criticism, the topics chosen by the magazines to represent their adherence to national identity focus on curbing the sexuality of female adolescents.

-

Sex is a topic that teen magazines treat with great caution. In a western context it is easy to publish an article like 'Do I need parental permission to get birth control?'.[53] In Indonesia the main theme is always 'How not to engage in premarital sex' as opposed to 'How to have safe sex', a topic that frequently features in western teen magazines. Licensed international magazines in Indonesia have to adapt to a 'local' style in order to acknowledge local values in their rhetoric. For example, CosmoGirl Indonesia published an article about sex education in its December 2002 issue. It was criticised by one of the readers:

I am criticising your article about sex education. You said that beautiful sex is the one done at the right time with the right person, when you are mature. You should correct that, sex is beautiful if you're married. The reason is that when we engage in a relationship, we all feel mature and think of our partner as the right person, which leads them to think that it is all right to do the things you're not supposed to do and not allowed to do.[54]

The editor's response to the above letter was:

If you read the part in the article about the risk of premarital sex, especially the part about pregnancy, you will realize that CG! is very much against premarital sex.[55]

-

Unlike licensed magazines which might be having problems 'localising' their content, Gadis, Kawanku and Aneka Yess! are all familiar with this territory because they are local. One of the methods employed by these local magazines to indicate that they still adhere to local tradition is to infuse religion into sex education. Subtly, this dichotomises east and west by implying that the west is a secular society only best consulted on worldly issues (such as physical beauty) as opposed to the spiritual east which holds the higher moral ground. Sexual discourse in girls' magazines is therefore frequently dissociated from the body and is often linked more closely with its social and spiritual (religious) meanings. An article about sex education opens the discussion with this line:

'If you think about it, it doesn't make any sense, does it, how can a baby pass through such a small opening like the vagina?' asked Chica in amazement.

'That is the Glory of God, Cha...'[56]

-

With its frequent emphasis on social and moral aspects, sex education in female teen magazines is carried out by instilling the fear of God and social punishment into young female readers. The discourse of sex education invariably evades the serious practical issues of sexual intercourse and pregnancy prevention, with which western magazines can deal without hesitation.[57]

-

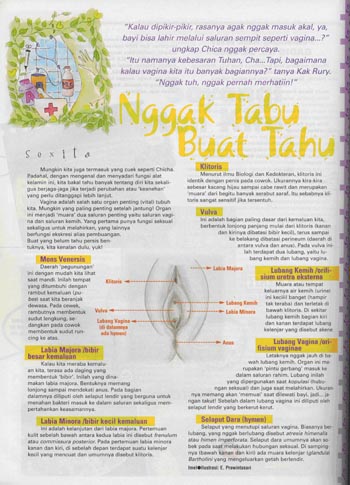

Sex education in Indonesian girls' magazines consists of basic anatomy and not physiology, as shown in Figure 5 which is an explanation about the vagina. It reads:

Vagina/orifisium vaginae. This is the 'gateway' to the womb. This orifice is used for copulation (sexual intercourse) and also for giving birth.[58]

This article does not explain what happens to these anatomical parts and how they are used during sexual intercourse. (The vagina is used for sexual intercourse – yes, but used in what way? How?). It assumes that readers already know from some other source.

-

The point I am arguing here is that sex education in this case is used to put in the 'local flavour'—that is to differentiate Indonesian magazines from western teen magazines and their 'immoral' approach

Figure 5. Figure 5: Sex education for girls. Explaining the vagina. Source: Gadis, no. 25/XXX, 16–25 September 2003, no page number.

Figure 5. Figure 5: Sex education for girls. Explaining the vagina. Source: Gadis, no. 25/XXX, 16–25 September 2003, no page number.

|

|

to sex education. Sex education in the content of Indonesian teen magazines is a symbolic performance of the magazines' role in fulfilling their obligation to respect local discourse on sexuality. It is interesting to see how sexuality is used as a mental partition to differentiate the west from the local in these magazines. It is used to establish an Indonesian, non-western identity by constructing difference around sexual morality, in order to draw a line between good Indonesians and bad westerners. The following quotations are taken from an article where readers were asked for their opinions about unacceptable 'western culture.' Notice how the words 'free-sex' keep coming up. 'Free-sex' in the Indonesian context is used to mean either casual or premarital sex:

Stuff that we don't have to copy [from the westerners]: their free culture and lifestyle (like free sex, etc.). For this kind of stuff, we have our own culture, lifestyle and personality, which I think is way cool.

But I think we don't have to imitate the way they [westerners] dress which is too revealing, or do drugs and free sex.

Things that we really shouldn't copy [from the westerners] are: free sex, the way they dress, and their individualist attitude.[59]

|

In the same magazine another article blames premarital sex for being the source of sexual assault:

According to research, if someone has been sexually active (has had sexual intercourse) that person will be addicted. Once he really wants to do it, he would do anything to be able to do it, even without love! He would easily resort to free sex... or do something criminal like raping! Eeuuch... [60]

-

Although the word 'ia' in the Indonesian language is genderless, from the context it is clear that 'ia' refers to 'he' as translated above. The last sentence indicates that a sexually active unmarried male is introduced to readers as a potential rapist. Even though the article does not refer to a sexually active unmarried person as 'western,' by connecting the article to the previous quotations about unacceptable western culture that keep emphasising 'free-sex' as a western attribute, the image of the west is conjured up as a bad example by association.

-

Although premarital sex is frowned upon inIndonesia, it is practised among Indonesian youths, often in the context of clandestine relationships and occasionally when young people cohabit prior to marriage.[61] However, local discourses maintain that these phenomena have no roots in Indonesia, which reflect what Bennett refers to as, 'the apparent gaps between sexual ideal and sexual behaviour.'[62] When teen magazines discuss female appearance, the west symbolises progress and sophistication. But, in articles discussing sexual morality, the west is constructed as oppositional and distant ('this does not happen in our society') in order to fulfil the magazines' duty to uphold a public discourse that respects an invented traditional gender ideology that focuses on female purity and chastity prior to marriage.

-

In an article entitled 'Dress Sexy. Why Not?' readers were asked for their opinions about wearing sexy out-fits. Here are some of the responses:

It doesn't suit our culture. Guys' eyes will strip you off....

That's western culture, man! Well, you'll look unique, but it's so overdoing it and inappropriate. Why would you want to flaunt your body? I don't think I would ever have a crush on a girl like that.

I don't like girls who wear sexy outfits, it's just showing your body too much, not to mention how that would make guys have nasty thoughts.[63]

Here western culture is seen as a bad influence and as degrading female sexuality by encouraging the male gaze. The comments above seem to ignore the fact that some of Indonesia's traditional costumes are see-through, tight and revealing and the fact that most of the models in the same magazines wear these kinds of outfits. So there is a discrepancy between public discourse and practice as Bennett argues.

-

Although beauty ideals are guided by western influences, local discourse plays an important role in justifying or normalising control over the display of female bodies and beauty. In the above article, the practice of wearing skimpy and tight outfits by female adolescents is counteracted with a discourse that posits that an overly-revealing outfit is not 'our' culture (as opposed to 'their' western culture).

-

An article about beauty contests (which originated in America in 1921)[64] contained encouraging comments, interesting facts and glamorous images of winners of beauty pageants. The article then slipped in comments about Indonesia's stand with regards to beauty contests:

Hmm ... you know, don't you, that Indonesia is one of the countries that consistently does not want to be involved in any international beauty pageants. The reason is that they are not in line with our country's cultural values.[65]

-

Considerable media discourse is directed against the swimsuit parades in beauty pageants, claiming that they break the eastern rule of modesty with regards to public displays of beauty. However, the article goes on to explain Indonesia's own version of the beauty contest:

Putri Indonesia [the name of the pageant, meaning 'Indonesian princess'] requires the 3Bs, which is the combination of Brain, Beauty and Behaviour. This year's pageant has recorded that 3 percent of the finalists are postgraduate students.[66]

Indonesia's non-participation in international beauty contests is compensated for by the country holding its own local pageants which do not objectify women in swimsuits, but which do judge women in traditional costumes. This example shows how fluid and yet, at the same time, how rigid the constructions of ideal femininity placed before the adolescent female gaze can be. It is fluid in practice but rigid in discourse. And, in both cases, western influence exists as a yardstick in the background.

-

To define local sexual morality, the west is posited as the 'other,' which is somewhat morally disagreeable but still understandable. 'They' are behaving just the way they are because they are westerners. An article about Simon Webbe, a member of an English boyband called Blue, illustrates this. In a gossip column in Gadis, it is revealed that Simon Webbe posed nude for a book:

Oops, you would never have thought that Simon Webbe posed nude for a book entitled 'How to Behave in Bed'. Hmmm, from the title you can guess that this is an adult book. Especially with Simon's pose and athletic dark body. But this is an educative book, though. Through Blue's spokesperson, Simon admitted that he used to model before he was in the boyband with Duncan, Lee and Anthony. 'It was a long time before he found fame in Blue,' said the spokesperson. Regardless of how long ago he modelled for the book, Simon's sexy pose is still a shock.[67]

The tone of the article does not express concern or disdain for the nude picture scandal. It treats the information lightly because the person involved is not Indonesian. Indonesian adolescents are represented in the magazines as innocent and pristine. This double standard in representing foreign and local sexuality is culturally constructed to emphasise the virtue of local norms.

Concluding remarks

-

Indonesian teen magazines use a 'western' physical appearance as a model of performance and appearance for ideal Indonesian adolescent bodies. Popular representations of adolescent girls reflect young women with light skin, who wear green/blue/grey/ contact lenses. They are relatively tall and fashionable, and are familiar with a modernised and westernised lifestyle.

-

The magazines negate the existence of diverse adolescent groups around Indonesia, who are not all as privileged as their peers represented in the magazines. Instead these teen magazines construct Indonesian adolescents as an homogeneous upper-to-middle class social group, in which wealth and urban lifestyle are the norm. Although it is not always verbally stated or explicit, westerners are strongly associated with images of affluence, sophistication and privilege. The reference is made apparent from representations and discourse in the magazines.

-

However, representations of the west that merge in discourses about pop culture and pop appearance become divergent in the dominant discourse on sex and sexuality. The separation of Indonesia from the 'west' serves to differentiate moral character and identity by opposing Indonesian adolescent asexuality and morality with western sexuality and moral degeneracy. The result is teen magazines with hybrid representations where local norms and global performances interweave. This demonstrates how the practice and discourse of performance can be contradictory and yet exist side by side in popular magazines.

Endnotes

[*] This paper is part of a Master's thesis at the University of Western Australia, which was sponsored by the Australian Development Scholarship from 2002 to 2005.

I would like to thank Lyn Parker, Linda Bennett, Carolyn Brewer and the two anonymous referees for their valuable input and comments.

[1] TVRI 1962, RCTI 1989, SCTV 1990, TPI 1991, Anteve 1993, Indosiar 1994, Metro TV 2000, TV7 2001, La-Tivi 2001, Global TV 2001, Trans TV 2001.

[2] See Philip Kitley, Television, Nation, and Culture in Indonesia, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 2000, p. 99.

[3] Marjorie Ferguson studied women's magazines across a thirty-year time period (1949–1980) and came to the conclusion that 'Everything changes and nothing changes'. The magazines seemed to have modern presentations, but the messages of femininity remained the same. See Marjorie Ferguson, Forever Feminine: Women's Magazines and the Cult of Femininity, London: Heineman Educational Books, 1983, p. 190.

[4] Suzanne Brenner, 'On the public intimacy of the New Order: images of women in the popular Indonesian print media,' in Indonesia, vol. 67 (April 1999):13–37, p. 16.

[5] Judith Williamson, 'Woman is an island: femininity and colonization' in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, c 1986, pp. 99–118, p. 106.

[6] Merry White, 'The marketing of adolescence in Japan. buying and dreaming,' in Women, Media and Consumption in Japan, ed. Lise Skov and Brian Moeran, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1995, pp. 255–73, p. 261.

[7] Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess and Gloria Jacobs, 'Beatlemania: a sexually defiant consumer in subculture?' in The Subcultures Reader, ed. Ken Gelder and Sarah Thornton, London; New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 523–36, p. 532.

[8] Lenore Manderson and Pranee Liamputtong, 'Introduction', in Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia. Youth, Courtship and Sexuality, Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 2002, pp. 1–16, p. 2.

[9] See, for example, Margaret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa, Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1943 and Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry III, Adolescence: An Anthropological Inquiry, New York, Toronto: Macmillan, 1991.

[10] Louise J. Kaplan, Adolescence: The Farewell to Childhood, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984, p. 336.

[11] For a brief history of Indonesian pemuda see Adrian Vickers, A History of Modern Indonesia, New York: Cambridge University Press. 2005, pp. 75–84.

[12] Jean Gelman Taylor, Indonesia: Peoples and Histories, New Haven; London: Yale University Press. p. 6.

[13] Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, Women and the Colonial State: Essays on Gender and Modernity in the Netherlands Indies 1900-1942, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000, p. 189 and Terence H. Hull, The Marriage Revolution in Indonesia, Atlanta: Population Association of America, 2002, p. 2.

[14] Hull, The Marriage Revolution in Indonesia, p. 2.

[15] See Djoko Hartono and David Ehrmann, 'The Indonesian economic crisis: impacts on school enrolment and funding' in The Indonesian Crisis. A Human Development Perspective, ed. Aris Ananta, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003, p. 183.

[16] See Richard Robison, Indonesia: The Rise of Capital, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1986.

[17] 'Ben Anderson ttg PEMILU' [Ben Anderson on the General Election] (my translation), 7 July 1997, online: http://www.hamline.edu/apakabar/basisdata/1997/07/07/0001.html, site accessed 31 October 2003.

[18] For examples of this see Lyn Parker, 'Engendering school children in Bali,' in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 3 (1997):497–516, and 'The subjectification of citizenship: student interpretations of school teachings in Bali,' in Asian Studies Review, vol. 26, no. 1 (2002):3–37.

[19] Saya Shiraishi, Young Heroes. The Indonesian Family in Politics, New York: Cornell University, 1997, p. 149.

[20] 'Ben Anderson ttg PEMILU.'

[21] David Bourchier and Vedi R. Hadiz (eds), Indonesian Politics and Society. A Reader, London: New York: Routledge Curzon, 2003, pp. 45–49.

[22] Shiraishi, Young Heroes, p. 149.

[23] Bina Graha Cabut Pembatalan SIUPP' [Bina Graha to Cancel SIUPP], in Kompas Online, Wednesday, 27 May 1998, online: http://www.seasite.niu.edu/indonesian/Reformasi/Chronicle/Kompas/May27/bina01.html, site accessed 28 October 2004.

[24] Rhenald Kasali, 'Dugem' [Clubbing], in Kontan, online: http://www.kontan-online.com/05/10/manajemen/man2.htm, site accessed 3 April 2003; no longer available.

[25] I would like to thank Pam Nilan and Kathryn Robinson for this qualification, that globalisation is rarely associated with the positive side of technology, trade and communication.

[26] Amien Rais, 'Moralitas Politik Muhammadiyah,' as cited in RB. Khatib Pahlawan Kayo, 'Problematika Dakwah Masa Kini' [The Contemporary Problems of Teaching Islam], in Majalah Tabligh, Dakwah Khusus, vol. 1, no. 12 July 2003 (my translation), online: http://www.muhammadiyah-online.or.id/mtdtkvol01_12.asp, site accessed 31 October 2003; no longer available.

[27] From the latest census in 2000, adolescents make up approximately 22 percent of the Indonesian population or around 44 million. For the latest year of Indonesian census see 'Pendahuluan. Penduduk Indonesia,' in Statistics Indonesia, online: http://www.datastatistik-indonesia.com/content/view/926/948/, site accessed 23 June 2008; for the percentage of Indonesian adolescents see 'Rubrik Kespro Remaja. Lomba Karya Tulis Remaja' in BKKBN, online: http://www.bkkbn.go.id/article_detail.php?aid=462, site accessed 23 June 2008.

[28] Ada Gula Ada Semut, Ada Kita Ada Iklan, online: http://www2.kompas.com/kompas-cetak/0305/09/muda/301674.htm, site accessed 23 June 2008.

[29] According to an A.C. Nielsen Survey in Indonesia: World Magazine Trends 2001/2002, online: http://www.magazineworld.org/assets/downloads/IndonesiaWMT01.pdf , site accessed 2 August 2004; no longer available.

[30] A.C. Nielsen Survey in Indonesia: World Magazine Trends 2001/2002.

[31] Kawanku started as children's magazine. I have no available information as to when it converted into girls' magazine.

[32] Vicki Shields, 'Advertising visual images: gendered ways of seeing and looking,' in Journal of Communication Inquiry, vol. 14, no. 2, (1990), pp. 25–39, p. 25.

[33] Gaye Tuchman, 'Introduction: the symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media', in Hearth and Home: Images of Women in the Mass Media, ed. Gaye Tuchman, Arlene Kaplan Daniels and James Benet, New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, pp. 3–38, pp. 8, 17–24.

[34] Ros Ballaster, Margaret Beetham, Elizabeth Frazer and Sandra Hebron, Women's World: Ideology, Femininity and the Woman's Magazine, London: Macmillan, 1991, pp. 9–10.

[35] I am using Benedict Anderson's concept of imagined communities as the result of print capitalism, in this case the teen magazine industry, to create a sense of community for Indonesian adolescents. See Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, 1983, pp. 41–49.

[36] Carla Jones, 'Dress for sukses: fashioning femininity and nationality in urban Indonesia,' in Re-Orienting Fashion. The Globalisation of Asian Dress, ed. Sandra Niessen, Ann Marie Leshkowich and Carla Jones, Oxford; New York: Berg, 2003, pp. 185–213, p. 192. See also Pam Nilan, 'Mediating the entrepreneurial self: romance texts and young Indonesian women', in medi@sia, ed. T.J.M. Holden and T. Scrase, Oxford: Oxford University Press [in press].

[37] Merry White, 'The Marketing of Adolescence in Japan: Buying and Dreaming,' p. 261.

[38] A paper about skin whitening appears in Intersections. See Patricia Goon and Allison Craven, 'Whose debt?: globalisation and whitefacing in Asia,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, issue 9, August 2003, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue9/gooncraven.html, accessed 21 May 2008.

[39] Dédé Oetomo as cited in Hannah Beech, 'Eurasian invasion,' in TimeAsia, vol. 157 no. 16, April 23, 2001, online: http://www.time.com/time/asia/news/magazine/0,9754,106427,00.html, site accessed 7 May 2004.

[40] Vanita Reddy, 'The nationalization of the global Indian woman: geographies of beauty in Femina,' in South Asian Popular Culture, vol. 4, no. 1, (April 2006), pp. 68 – 73.

[41] Sheila Cavalera, 'Pemutih Pembawa Bencana,' [The Whitening Lotion Disaster], in Aneka Yess!, vol. 4, 13–26 February 2003, p. 116, (my translation).

[42] Aneka Yess!, vol. 4, 13–26 February 2003, p. 135.

[43] Kelley Massoni argues that although in real life modelling is not that accessible as an occupation, girls' magazines' extensive coverage of models and modelling activities makes the profession more probable than it really is. See Kelley Massoni, 'Modelling work: occupational messages in Seventeen Magazine,' in Gender and Society, vol. 18, no. 1 (February 2004), pp. 47–65, p. 48.

[44] Aneka Yess vol. 19, pp. 11–24 September 2003, p. 126.

[45] Jones, 'Dress for sukses,' p. 200.

[46] Although not discussed here, having a prominent nose is also deemed as one of the western physical traits hailed as the ideal female beauty. Efforts ranging from cheap make-up techniques to expensive plastic surgery have been used by Indonesian females to get the 'ideal' nose. Plastic surgery is never discussed in these girls' magazines, but they do provide make-up tips to achieve the effect of a more prominent nose.

[47] Gadis, 25/XXX, 16–25 September 2003 (my translation). Some issues of Gadis magazines do not have page numbers.

[48] Kawanku, 32/XXXII, 3–9 February 2003, p. 71 (my translation).

[49] Aneka Yess! vol. 23, 7–20 November 2002, p. 78 (my translation).

[50] A term coined by Gordon Mathews to depict culture as a matter of choice instead of being purely inherited, in Global Culture/Individual Identity: Searching for Home in the Cultural Supermarket, London; New York: Routledge, 2000, p. 5.

[51] 'Nationalising' the beauty is a term from Reddy, 'The nationalization of the global Indian woman.'

[52] Susan Bordo, The Unbearable Weight: Feminism Western Culture and the Body, Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993, p. 250.

[53] 'Do I need parental permission to get birth control?' in About.Com: Teen Advice. Teen Life Q&A Special: FAQ on Teen Pregnancy, n.d., online: http://teenadvice.about.com/library/weekly/aa060502g.htm, site accessed 28 September 2007.

[54] CosmoGirl Indonesia, January 2003, p. 14 (my translation).

[55] CosmoGirl Indonesia, January 2003, p. 14 (my translation).

[56] 'Sexita,' in Gadis, 25/XXX, 16–25 September 2003 (my translation).

[57] I compare it with English language magazines such as Cosmo Girl, Elle Girl, Girlfriend and Dolly.

[58] 'Sexita,' in Gadis, 25/XXX, 15–25 September 2003 (my translation).

[59] Gadis, 27/XXX, 7–16 October 2003 (my translation).

[60] 'Sexita,' in Gadis, 27/XXX, 7–16 October 2003 (my translation).

[61] Linda Rae Bennett, Sex, Power and Magic: Constructing and Contesting Love Magic and Premarital Sex in Lombok , Canberra, ACT: Gender Relations Project, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, c2000, pp. 44, 159–60, 168–69.

[62] Bennett, Sex, Power and Magic, p. 45.

[63] 'Tampil Sexy. Kenapa Nggak?' [Dress sexy. Why Not?], in Aneka Yess!, vol. 21, 9–22 October 2003, p. 28 (my translation).

[64] 'Mencari Yang Tercantik' [Searching for the Most Beautiful], in Gadis, 25/XXX, 16–25 September 2003, p. 61 (my translation).

[65] 'Mencari Yang Tercantik' [Searching for the Most Beautiful], in Gadis, 25/XXX, 16– 25 September 2003, p. 61 (my translation).

[66] 'Mencari Yang Tercantik' [Searching for the Most Beautiful], in Gadis, 25/XXX, 16– 25 September 2003, p. 61 (my translation).

[67] 'Miss Gosip,' in Gadis, 34/XXX, 27 December 2002–6 January 2003, p. 118 (my translation).

|