'I Love Dugem':

Young Women's Participation

in the Indonesian Dance Party Scene[*]

Harriot Beazley

Introduction

-

This paper explores the impact of the global phenomenon of electronic dance music culture (EDMC) on contemporary constructions of femininity in Indonesia. The focus is on the various methods young women use to establish 'a sense of place' in nocturnal dance spaces, through new forms of identity construction and public interaction. In particular I seek to demonstrate how this contemporary Western youth sub-culture has been influential in shaping a new form of femininity in Indonesia, and how this femininity is articulated through young women's involvement in the Indonesian 'rave' and dance scenes—known locally as parti or dugem (dunia gemerlap).[1] The paper considers how femininity, including female sexuality, is socially constituted through Indonesian state and mainstream discourse, and how young women are negotiating and challenging these hegemonic concepts of feminine identity through their participation in EDMC.[2]

-

In the paper I describe how global social processes have produced an intense spatial concentration of clubs, bars and other nocturnal spaces in Bali, and the opportunity for the social interaction of young people from all over the world. These transnational rave spaces provide Indonesian young women with new sites of enjoyment and pleasure, where they are able to express themselves in ways that they cannot elsewhere.[3] Specifically, the paper considers how young Indonesian (Javanese and Balinese) women entering dugem Bali—Bali nightlife—are able to dissolve the temporal and spatial boundaries imposed by dominant discourse, through the negotiation and shaping of shifting identities, across day and night. In particular, I explore young women's expressions of alternative identities when participating in the dance party scene, as articulated through their conversation, bodily style, alcohol and drug use and choice of sexual partners. I see these behaviour patterns as 'geographies of resistance' by young women in Indonesia,[4] and as a response to the ideological construction of femininity within Indonesian society, a society which believes that young unmarried women should not be out at night.[5]

-

Through an analysis of their nocturnal activities, I demonstrate that young women are not passive recipients of hegemonic gender socialisation within Indonesia, but are active agents in the construction of their feminine identities and the negotiation of their lived expressions of gender. By providing an insight into young women's involvement in the rave sub-culture, and how young women simultaneously negotiate and construct gender in a predominantly patriarchal society, I consider the wider concepts of youthful subjectivity and femininity in Indonesia.

-

The paper draws on ethnographic fieldwork conducted with young women participating in the dance party scene in Bali, over a period of sixteen months, between 2001 and 2006. The ethnographic methods employed included participant observation, structured observation at dance parties, clubs and raves, semi-structured interviews, and in-depth interviews with eleven young women.[6] I met all the respondents through my participation in the dance party scene, and through personal introductions.[7] The research for the study took place in bars and clubs in Kuta, Legian and Seminyak, Bali. Further observations were recorded at organised outdoor 'raves' and 'parties,' and private villa parties and 'after parties' throughout the island of Bali. The majority of the women who participated in this study were between the ages of twenty-two and thirty-six years and were Balinese or Javanese, either visiting or living in Bali.

-

I begin the paper by setting up the theoretical framework and reviewing the ideological constructions of femininity in Indonesian society. This is important in order to fully assess what it is that young women are resisting in Indonesia, at a time of political transition, democratisation, Islamisation, and the rise of a new social conservatism, together with the intense flow of global capital and ideas into Indonesia. I then explore 'rave' and the dance party scene from a global perspective, and how this relatively new sub-culture has proliferated and mutated into various hybridisations, reaching Indonesia's shores in the mid-1990s. Once these parameters are established, in the second half of the paper I consider how and why the nocturnal spaces and events within the rave scene are enjoyed by young Indonesian women. Young women mainly see these occasions as sites of transgression, pleasure and enjoyment, which are relatively free from violence and societal constraints.

Theoretical framework

-

The theoretical framework for this paper draws on discussions around global youth sub-cultures, including the phenomena of 'rave,'[8] together with debates about the ideological construction of femininity in Indonesia.[9] I also draw on my own work on street girls' sub-cultures in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, which is informed by Steve Pile and Michael Thrift's concept of 'Geographies of Resistance.'[10]

-

Throughout my analysis I am informed by the theoretical frameworks of post-structural and sub-culture theorists from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) in Birmingham,[11] and critiques of these which focus on women's roles in sub-cultures.[12] According to the CCCS, youth sub-cultures resisted subordination through the production of their own subversive styles, such as those of punks, mods, rockers and skinheads. These sub-cultural resistance styles have spread throughout the world, via the media (radio, music, TV and the internet), and have been received differently in different countries and regions of the world, as global media influences have been localised and hybridised to suit local culture.[13] Since the 1970s, the work of the CCCS has been expanded by academics from a variety of disciplines, including cultural geography, in a discussion known as 'post-subcultural studies' that emphasises the complexity, diversity and syncretistic aspects of youth cultures as they localise global youth cultures.[14]

-

There has been a focus within cultural studies and cultural geography on the phenomena of 'rave' and club (sub)cultures that have spread throughout the world,[15] as well as the phenomenon of Hip Hop as a new global youth sub-culture.[16] These studies have included some thought-provoking texts on women in the UK rave scene.[17] The reason I have chosen to draw on Western theorists to understand aspects of Indonesian rave is that to date there are no other studies about local men or women participating in the rave scene in a 'developing' country.[18]

-

Many feminist approaches to youth sub-culture have criticised sub-cultural theory for ignoring feminist issues, and point to the masculine and sexist elements of sub-cultures which marginalise girls.[19] In addition, and central to the concept of a 'culture of femininity'[20] among feminist sub-cultural theorists, is the contention that girls negotiate a different social space from boys, and that those girls who enter the male territory of public space do so on male terms, as girlfriends, appendages or whores.[21] Angela McRobbie in particular stated that sub-culture itself may not be a place for 'feminine excitement.'[22]

-

More recent studies within the discipline of young people's geographies in the UK have shown how public spaces provide an important social venue for young girls, as well as for boys, but that their use of space often conflicts with that of boys.[23] Girls in public spaces often find that they are conceptualised as 'being the ?wrong? gender and being in the ?wrong? place.'[24] As Tracey Skelton argues, girls will frequently resist such a marginal positioning, especially through their friendships, and the ways they use public space to create their own social worlds. The rave and club culture in the UK has recently been identified by feminist scholars as one such site in which female adolescents and young women can create their own social world and construct their own cultural identity.[25] Rave culture, it seems, has brought equality to nightscapes, enabling young women to explore new spaces of social interaction and new modes of femininity.[26]

-

This current research builds on my doctoral dissertation which was an ethnographic study of street boys and street girl sub-cultures in the city of Yogyakarta, Java. Within the thesis I explained how through different strategies of resistance, including 'geographies of resistance' to mainstream discourse on how a 'good girl' should behave, street girls constructed themselves as a 'micro-culture' which existed beside, and interconnected with, the dominant male sub-culture of street boys. By examining the lives and experiences of twelve street girls (aged between twelve and twenty), I showed how sub-cultural options were available to them, and I explained the girls' behaviour patterns as survival mechanisms and strategies of resistance, which were articulated through their discourse, style, and income-seeking and leisure activities.[27] I also explained how the girls and young women living on the streets negotiated different social and personal spaces for themselves, and how they succeeded in creating their own gendered space on the street. Drawing on Pile and Keith[28], I presented these socio-spatial patterns as 'geographies of resistance,' as a response to the patriarchal discourse within Indonesian society that girls in particular should not be on the street. By building on the work of Alison Murray[29] the research identified that although there appears to be a culture of conformism to gender ideologies in Indonesia, there in fact exist alternative interpretations of gender within society, and many of them are voiced by women.

-

In this analysis of young women entering the Bali rave scene, I expand on the theoretical model of gendered 'geographies of resistance' to illustrate how, by being part of another youth sub-culture in Indonesia, the rave sub-culture, young women in Bali are able to construct further geographies of resistance to their marginal positioning within dominant cultural models of femininity. I explore how the assimilation of global youth culture in the form of 'raves,' 'parties' and the headlining of international DJs at various venues in Bali, has created new spaces of social interaction and identity construction for young Indonesians, particularly young females.

Constructions of femininity in Indonesia

-

The lives of young women in Bali, Indonesia cannot be explained without first understanding the Indonesian New Order state's ideological construction of femininity, which was reproduced through society's discourse, and which is described below. More specifically, it is important to recognise how these ideological constructions played out in public spaces, and how young women were expected to conform to specific codes of dress and behaviour within these spaces. Further, although a thorough discussion is outside the scope of this paper, it is also important to acknowledge contemporary debates concerning gender constructions within post-authoritarian Indonesia, particularly within the context of a new focus on regional issues, and the subsequent reinforcement of patriarchal values which have had significant repercussions for Indonesian women in conservative Islamic areas, as well as in Bali.[30]

-

During Soeharto's time in power (1966–1998), known as the 'New Order,' ideological indoctrination aided the state's attempts to create a culture of conformity for uniting a highly diverse and unequal society. One of the ideologies constructed by the New Order state in the pursuit of power was a sex and gender ideology, 'State Ibuism.'[31] State Ibuism repressed women by emphasising their 'traditional' roles, placing them in a subordinate position to men, and defining them in narrow stereotypical roles of housekeepers and mothers (Ibu). Gender stereotyping of girls bound them to their future roles as mother and caretaker of the family home. Mobility restrictions were also enforced, particularly once a girl reached puberty. This was because girls in Indonesia were believed to need guidance and sexual protection, and their movements were restricted to the 'safe' environment of the family home, a household, or a safe workplace. Consequently, most young women in Indonesia have grown up with a limited spatial experience, and an awareness of the night as 'dangerous.' Further, social stigma and stereotyping were key mechanisms that reinforced many of the restrictions placed on women in Indonesian society.

-

For women and women's groups throughout Indonesia, the post-Suharto era of democratic reform [reformasi] brought with it the hope of new opportunities for changes to long-standing gender relationships and to social and political structural inequalities?Nevertheless, the gains for women have been largely rhetorical rather than practical.[32]

-

In spite of the fall of Suharto in 1998, and the subsequent opening up and democratisation of the nation, women in 2008 are still oppressed by New Order ideology, including State Ibuism. Although Suharto is now dead, New Order ideologies are still imbued throughout Indonesia's social institutions, and are so deeply engrained in Indonesian society's psyche that they will take many more years to disappear. Further to this, since the fall of Suharto the gendered ideology of the nation state has found parallels within Balinese patriarchal cultural and social institutions, and within strongly Islamic areas of Java.[33] In the post-Suharto era, it is important to therefore briefly consider not only if forces of State Ibuism still have some influence, but also how manifestations of Islamisation within Java and regionalism in Bali may have impacted on local expectations of how young Javanese and Balinese women should dress and behave.

-

In spite of—or perhaps because of—the surge of democratic processes and reformasi that followed Suharto's demise, the late 1990s signalled a new phase of Islamisation and jilbabisasi (taking the veil) and the wearing of modest dress by Indonesian Muslim women.[34] The trend has intensified since the fall of Suharto, and—in addition to being a statement of women wishing to show their piety—jilbabisasi can be understood either as a politicised discourse among lower middle-class women, or as consumerist discourse among urban elite women who celebrate the veil as a modern and fashionable phenomenon.[35] In contrast to the consumerist discourse of the veil, the politicised discourse reflects a discontent with the current socio-political climate in Indonesia that still adheres to a New Order development rhetoric which privileges the already empowered middle class and neglects the 'other middle class' (teachers, lower ranked civil servants and other professionals without social power), who have subsequently opted for an 'alternative modernity through the practice of Islamism.'[36] Either way, this new trend towards radical Islamic politics which upholds austerity, purity and innocence, signals a shift in gender relations in Java and the increased possibility of the (re)production of conservative sex roles and increased restrictions on women's dress and behaviour.[37]

-

As well as Islamic revivalism in many areas of Indonesia, the fall of Suharto and subsequent process of decentralisation, has led to a rise in concern about regional cultural identities and how this impacts on gender relations in Bali.[38] As Helen Creese says:

The re-conservatism and the reinforcement of patriarchal values that stem from this new focus on regional issues have already had considerable repercussions for Indonesian women on who the burden of restrictive practice falls most heavily. This impact has been striking in Islamic areas, but it is also true in Bali where issues of gender intersect closely with calls to regional identity.[39]

-

This has been particularly true since the Bali bombs of October 2002 which exploded outside two Balinese nightclubs (in itself a brutal expression of how certain Islamic rogue elements of Indonesian society view Bali nightlife). Shortly after the bombing, a media campaign to preserve Balinese identity and culture, before it was tainted any further by the West, began. The campaign's slogan, Ajeg Bali (Strong Bali), encompasses all aspects of Balinese tradition, religion and culture, and represents 'a drive for stability and cultural certainty in a chaotic world.'[40] This new definition of Balinese identity sees the West and modernity as antagonistic to Balinese values. In this reshaping of contemporary Balinese identities women are expected to conform to certain gender roles, so as to preserve Balinese culture, while modern autonomous women who participate in global culture are seen as a direct threat to Balinese values.[41] In practice this points to a revival of patriarchal beliefs that Balinese women are responsible for the well-being of their families and for the ritual health of their families, and belong at home.

-

As a result of the New Order's ideological legacy, compounded by Islamisation in Java and the Ajeg Bali foment, there remains a distinct distrust of women who break any of the unwritten rules, act independently, wear inappropriate clothing or leave the 'traditional sphere' of the home and family. During my research I asked young women to tell me exactly what was expected of young women by mainstream society. They answered that women in Indonesia are not permitted to go out after 9.30 p.m., they cannot go where they please, they cannot drink alcohol, they cannot take pills or smoke, they cannot have sex before marriage, they cannot wear 'sexy' clothes, and they cannot leave the house without permission. They must be good, nice, kind and helpful, and stay at home, and not go out at night. A woman out at night without a man (brother, husband, uncle), still defies most mainstream conventions in Indonesia. Young women who do not conform to the female stereotype of staying at home at night, out of sight, being the passive 'ideal' daughter, wife or mother, are regarded with suspicion and are stigmatised and labelled as 'bad girls.' If they are out late at night and seen to be dancing in nightclubs, dressed in sexy clothes, their behaviour is automatically linked to their sexuality, and they are considered to be 'perempuan nakal' (a 'bad' woman), or WTS / Wanita Tuna Susila (a 'Woman Without Morals'): a prostitute.

Rave and EDMC: a growing global sub-culture

-

The term 'rave' describes the UK sub-culture that grew out of the Acid House movement which was at its peak in the summer of 1988, later known as the 'Summer of Love.'[42] Twenty years later, in 2008, the dance party scene is still going strong and has spread across the globe, as Graeme St John explains

The dance party rave—involving masses of young people dancing all night to a syncopated electronic rhythm mixed by DJs—maintains rapturous popularity in the West, developing diasporic tendrils from Ibiza to London, West Coast USA to Goa, India, Japan to South Africa, Brazil to Australia, and tourist enclaves from Thailand to Madagascar. Commonly accorded effects from personal 'healing'?to transformations on social, cultural or political scales, rave—from clubland to outdoor doof?—is a hyper-crucible of contemporary youth spirituality.[43]

-

'Rave' describes a musical genre, encompassing a style of electronic dance music ('Techno,' 'House' or 'Trance'), and dance which usually takes place at all night dance parties, either in clubs or outdoor settings,[44] often (but not always) sustained by drug use, most notably amphetamines and MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) or 'ecstasy.'[45] Historically, all youth sub-cultures have an association with a particular drug and rave culture is no exception. Ecstasy is usually taken in tablet form. It works in the body by raising the levels of the hormone oxytocin, which is known to reduce inhibitions and to promote interaction between people, making them feel euphoric and significantly more trusting and empathetic with other people.[46] These feelings are accentuated by listening to music with a repetitive beat, such as electronic dance music. Rave participants thus experience a sense of communality by responding to the music through dancing together, a positive change of mood, and through spoken and unspoken interaction with other ravers.

-

Electronic dance music culture (EDMC) or rave has been described as 'The first distinct and significant youth sub-culture to emerge since the Birmingham School days of punk rockers and skinheads.'[47] It is also described as the 'sub-culture of peace' due to the principle philosophy of rave, which has the slogan of PLUR, an acronym for Peace, Love, Unity and Respect.[48] The ethos of rave is that anyone, no matter what their beliefs or socio-economic and educational status, can participate.[49] Typically, therefore, EDMC can be understood as a culture of peace, and raves are peaceful events, often situated amidst a society of violence.[50]

-

Within academic literature, rave is still predominantly understood as a Western youth sub-culture (even when it takes place in exotic locations), and almost all social and ethnographic research into participants' experiences of rave culture are focused on the West, or on Westerners who participate in raves in the developing world, most notably in Goa (India) and Koh Phangan in Thailand.[51] Few, however, are aware that there is a growing indigenous rave scene in these and other developing countries, and little has been written about them.[52] In particular there is very little understanding about the impact of this new global youth sub-culture on local societies. Most studies agree, however, that 'Electronic Dance Music Culture is a truly heterogeneous global phenomenon.'[53]

-

During the early 1990s, an international network of dance music sites emerged along the routes of backpacker culture, where 'tourists directly influenced dance music scenes.'[54] Bali was firmly on this route, and clubs and bars began to emerge to cater for the new patterns of sub-cultural travellers (and expatriates) who sought electronic dance music. The music was not enjoyed by only Westerners, however, and it was not long before the culture began to gain popularity among Indonesian youth. In Indonesia, raves began in the underground club scene in Jakarta and Bali in the mid-1990s, when (similar to Thatcher's Britain in the 1980s) there was dissatisfaction with national politics while Suharto was in power. Indonesia's post-colonial connection to Holland also meant access to cheap drug production, which led to the mass distribution of ecstasy at clubs during what has been described as the 'Summer of Love a la Batavia' in 1995.[55] These events were routinely squashed in heavily armed raids known as 'ecstasy raids' which took place during the mid to late 1990s.[56]

-

The fall of Suharto in 1998 coincided with the rapid increase of organised 'raves' in Jakarta, Java and Bali. Now, in 2008, Indonesia is on the map for Western promoters and DJs, with dance parties pulling crowds of between 500 to 5,000 people, with up to 20,000 in Jakarta. Like raves on Thailand's island beaches, Jakarta and Bali entrepreneurs provide full moon dances at beach and cliff top locations, where young people dance to electronic dance music until sunrise or beyond. Smaller 'trance and black moon parties,' organised by individual (Indonesian and Western) DJs are held in specific clubs, at underground parties in Bali, and on nearby beaches and islands. The music usually begins at around midnight, while some clubs in Bali, including the legendary Double Six, do not start until 2 a.m., finishing at 7 a.m. or 8 a.m., with some outdoor raves continuing until midday.[57] There are a few clubs that do not open until 7 a.m., 'peaking' at 8 or 9 a.m., to catch the crowds leaving the bigger venues, and staying open until midday. There are also numerous private daytime 'after parties' at private villas throughout the island.

-

When young people go clubbing or to raves in Bali they talk about clubbing or dugem. Some people in Indonesia refer to a rave as a 'dance party,' but most people borrow the English word 'parti' or 'even' (event)—and English is always used in promotional literature. During my conversations and interviews at these events many young people spoke a bahasa gado-gado, mixing English and Indonesian when they spoke with me, and also with each other. When I asked someone why people used bahasa gado-gado they replied, 'to look 'cool,' or 'it's a cool language mixed up like that' ('biar look ?cool? bahasa kerenya gaul gitu loh').

-

One reason for the use of the English language in their discourse is that many young Indonesians think of Indonesia as backward, while they think of the West as dynamic, modern and progressive (maju). English is also the international language of youth culture and bahasa gado-gado is always spoken on Indonesian TV music channels such as MTV. Further, and as Erwin Ramedhan noted of the 1970s disco scene in Jakarta, 'discos and other places of social gathering not only have the function of ?amusement and fun? for youth sub-cultures, they are also places for social and material display of Western-style consumerism.'[58]

-

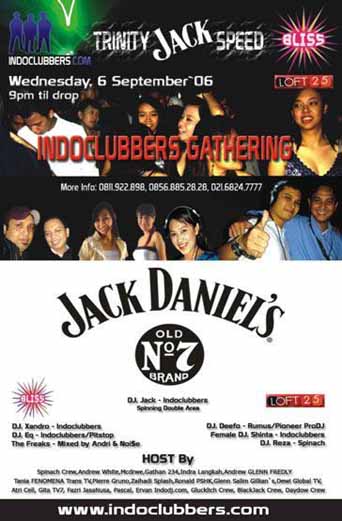

Following Arun Saldanha[59] and his research on the consumption of popular music in Bangalore, the consumption of rave music in Bali may be understood as an avenue which disconnects young people socially and spatially from 'local' Indonesia, by providing them with an imaginary geography that enables them to refute 'tradition' and local culture through the performance of post-traditional identities. However, even though participants use English to promote raves on flyers (see figure 1), and within some communication in internet chatrooms, as well as using bahasa gado-gado on the

|

|

dance floor, their acceptance of Western rave music is translocal.[60] As Saldanha found in Bangalore, the identity of rave participants in Bali is one that exists in the dialectic between the impact of the West and Indonesian tradition, 'a dialectic not subsuming into a synthesis but into something intrinsically different: something perpetually inbetween?.'[61]

As a result, these translocal practices of Indonesian youth are not homogeneous, and differ considerably from the translocal raving practices of 'global youth' in London, Sydney or Amsterdam.[62] From my own observations, for example, apart from the obvious differences of locations, I found people to be far more open and friendly (and in tune with the philosophy of PLUR) at clubs and raves in Bali than at any of the clubs or raves I have attended in London, Sydney, Melbourne, Singapore or even Jakarta.

Figure 1. Flyer for dance party event: Indoclubbers Gathering. From 'My public photos,' on friendster., 6 September 2006, online: http://www.friendster.com/photos/16395036/ 338850122/51041, accessed 9 July 2008.

|

-

The people who go to dance parties in Bali are as diverse as in the West. Participants ('clubbers' or 'ravers') at these events come from all over Indonesia, Singapore and elsewhere in the world. They can be as young as fifteen and as old as fifty. Most people are in their early twenties to mid-thirties. As one woman explained on a website:

they come from a variety of social classes; from parking attendants, executives, policemen, TNI (soldiers), students, and house wives. Even their ages vary from teenage youth to grannies who are almost dead (yg sudah bau tanah').[63]

Geographies of resistance: Dugem as a 'third space' for young women

-

Following Maria Pini and Angela McRobbie, who have researched women in the rave scene in the UK, the rave and dance party scene in Indonesia may be understood as a new nocturnal site for alternative constructions of female-self, at a time when conceptions of femininity in post-Suharto Indonesia are in flux. As Maria Pini in her analysis of women in the UK rave scene has observed:

For many women, rave represents an undoing of the traditional cultural associations between dancing, drugged, 'dressed up' woman and sexual invitation, and as such opens up a new space for the exploration of new forms of identity and pleasure.[64]

Similarly, Indonesian women appear to be using dugem as a temporary avenue of escape and a release from their normally circumscribed position in society. Following Hakim Bey and Homi Bhabha, I perceive the nocturnal spaces where young women engage in these activities to be 'Temporary Autonomous Zones (TAZ),[65] or 'third spaces,'[66] and as temporary sites of transgression and resistance that elude formal structures of control of the expected ways of behaving for young women in Indonesia.

-

The women involved in the rave scene in Indonesia may be understood as a group caught between two cultures, but who are constantly asserting their right to autonomy and independence. In this sense the club or rave can be regarded as an 'interstitial space' for young women, a terrain where 'strategies for elaborating selfhood, whether singular or communal, that initiate new signs of identity,' are contested.[67] From this perspective the rave becomes the 'third space,' 'where the newness of hybrid identities can be articulated.'[68] The claiming of these spaces by young women, and their performances within them, are geographies of resistance.

-

As elsewhere in the world, women in Indonesia have been denied the 'unsupervised adventures' celebrated in other male-dominated youth sub-cultures.[69] In Indonesia one sub-culture which has emerged as a typical example of a male dominated sub-culture where there is no room for women, is the punk sub-culture.[70] Emma Baulch's analysis of the punk and thrash metal scene in Bali clearly illustrates how it is a male dominated sub-culture, and that one rarely sees any women at these events.[71] My research suggests that in direct contrast to the punk sub-culture in Bali, EDMC in Bali allows for young women to participate and find adventure at dance parties and raves. This is because the inclusive nature of rave creates relatively safe spaces for women to express new modes of femininity and physical pleasure, where they can explore and experiment with alternative identities, identities that they would not and (increasingly in Indonesia) cannot express elsewhere.

-

Clubs and raves are, therefore, a critical venue in which to explore the changing modes of femininity, indicating a 'feminisation' of 'youth sub-culture' in Indonesia. Indonesian women enjoy these nocturnal places because their overt material display of a Western consumerist lifestyle is very different from that which is expected by the hegemonic discourse of how a good girl should behave. Further, what is unique to rave is the feeling of belonging that young women experience on the dance floor and within the scene more generally, and the fact that they can experiment with different identities, within a relatively safe and accepting environment.

-

As in other Asian countries, there is a distinct stereotypical perception held of Indonesian girls who are seen at clubs and raves: they are seen as prostitutes, and commonly labeled as ayam ('chickens'). This view is held by mainstream society, and by many foreigners:

BTW women in Indonesia who drink beer and smoke 'di depan' umum (in front of everybody) are WTS (wanita tanpa susila) for sure, women without moral.[72]

Although there are indeed many bar girls and 'prostitutes' operating in bars, nightclubs and at raves, there are many more girls at these events who are not in this market, and who are just there for a good time. As with female partygoers in the UK and Australia, many of the young women who frequent clubs and dance parties in Bali are middle or working class young women with jobs or their own businesses and money, looking for a good night out. This may include going home with a man, but not for money. Further, for the young women who are involved in sex work, and who sometimes operate as bar girls in the clubs, this is not the only reason that they attend the clubs and parties. They also go as they enjoy the scene, and like to dance, while sometimes they are looking for clients.

-

The women who participated in this study were from different socio-economic backgrounds, religions, classes and regions of Indonesia, although they were predominantly from Java, with a few coming from Bali. A significant majority of the respondents were Javanese migrants who had come to Bali to work and earn money to send back to their families. These young women were students or workers living in kos (cheap single-sex boarding houses), young professionals (lawyers, accountants, journalists, NGO staff), beauticians and salon workers; fashion designers; restaurant and hotel workers, owners of small businesses, and bar girls. Some of the young women I met were single mothers who had left their children in Java with their families. It struck me that these young women were already escaping the patriarchal grip of home in Java, and were looking for a new life in Bali, where they could have more freedom to do as they pleased. As one Javanese woman, Rini, aged 26, told me:

My parents are not here, they are in Java, so I am free here. But my parents don't know I like to go out [at] night like this. If they knew, for sure they would be really stressed because they are strongly religious. I could be ordered to go home. If they ask what I am doing? I'm busy at work. What is important is that every month I send money home because I am the oldest of three siblings. I am number 1 and so I have the responsibility to my family.[73]

Other Javanese women I met were from the middle class or high economic strata, and were young professionals who worked in Jakarta and came to Bali once a month or so, to escape the city. Some of these girls preferred to come to clubs in Bali as they were less likely to be recognised when they went out.

-

The Balinese young women I met who regularly enjoyed dugem mostly lived at home, came from stable family backgrounds and by their own accounts had good relationships with their parents, who expected them to get an education and then get married. These girls had restricted mobility compared to the girls who lived in kos or rented houses who did not have their parents supervising their activities, and who usually came home late enough in the morning that the doors had already been opened. Balinese girls still living at home had to be very careful how they negotiated their nightlife with the image they had in their family and local community. It was important to the Balinese girls that I spoke with that they maintained the 'good girl' image at home, and that no-one knew that they went to nightclubs and raves. The young women told me that they usually lied to their parents about where they were going, saying that they were going shopping at the mall with friends and staying at a friend's house, when they were really going dugem. This is an interesting issue that relates to women's traditionally dominant role in the market place and the rise of consumerism in Indonesia, and the fact that shopping is regarded as a feminine practice which is sanctioned by parents—while going to clubs or raves is not. The dominant discourse in twenty-first century Indonesia, therefore, allows girls to go shopping at night, which in itself demonstrates a refashioning of dominant constructions of femininity. As Made (22) told me:

On Saturday nights my parents think I am going to the mall with a girl friend, and then staying at her house, but if it is a normal night then I usually say that I'm going to study at a friend's house even though I'm going dugem.[74]

It is not only younger women still living at home who have to lie. As Evie from Java (aged 28) told me, when I asked her if her parents knew she went out at night:

For sure my parents don't know?but not everyone here knows that I'm already married and have one child. My husband is 65 years old. My neighbours don't know and I don't tell them I go out at night because I already make them uneasy. I don't want my husband and parents to know either.[75]

-

Women were at extreme risk of facing social sanctions from the local community if they were perceived to be behaving badly. For this reason the day-time parties were very popular with Balinese girls and young women living at home (or with their husbands), because it made it much easier for them to lie about where they were going.[76] One Balinese woman, Ketut (aged 33), maintained that her parents, particularly her father, did not mind that she went to clubs or events, as long as she was with friends or her boyfriend, as they considered her to be an adult. Interestingly, she indicated that the reason her neighbours and parents accepted her going out was because she was with her husband, who was a bule (foreigner/white man) from France:[77]

It's not only my parents who know?all my neighbours know too that I go out at night. Because I am a Balinese girl who has a bule [Western] husband, when I'm with my husband I go out at night. And I'm always polite to the kampung people. So they still respect me.[78]

It was clear, however, that this was unusual and that the majority of the young women who were freely participating in the scene were Javanese, with no familial restrictions. They did, however, have to maintain the 'good girl' image during the daytime, and when they were at work or university. These women told me that no-one at home or in their kampung in Java knew anything about what they did in Bali, and certainly did not know that they liked dugem.

-

The mainstream belief that all young women at nightclubs are prostitutes is resisted by female partygoers and was vehemently denied by the young women I spoke to, as well as by girls online. Girls who like to go to clubs and parties discuss this attitude on blogs and in internet chatrooms, and agree that the best response is to ignore these attitudes (cuwek). In this way they embrace their freedom and liberation from mainstream norms by actively rejecting society's view of them, and deciding to party anyway. Wayan, a young Balinese woman (aged 24), said to me about people in her kampung:

I don't care if they think I'm not a good woman. I can support myself and I am happy that I am not restricted by rules.[79]

Clearly then, the fact that many of these young women were working and earning their own money gave them feelings of empowerment and the confidence to behave in the way they did.

-

All the young women I met were introduced to dugem by their friends or their boyfriends, and they usually went out at night with groups of male and female friends. Some of the respondents said that they went to a bar before they went clubbing, to meet their friends and to begin drinking and dancing, to 'get in the mood,' and it appeared that many of them liked drinking alcohol. There are numerous bars in Seminyak and Kuta with resident DJs, where the atmosphere is very similar to a night club, and where young people often begin to party before the real night starts. In the bars young women drank cocktails, wine and spirits, and many had a disposable income with which to afford these drinks, or they let men buy drinks for them. I observed many women drinking alcohol, and most women I spoke with told me that they enjoyed drinking alcohol—a practice frowned on severely in mainstream society. As Made (22) said to me, 'If I go out at night I prefer to drink because with drink I feel more confident to speak to new friends or boys.'[80]

-

The cost of entry to an event varies depending on the club or rave party. Some are cheap at Rp.25,000 ($AU3) entry, but entrance prices can be anything from Rp.50,000 ($AU8) to Rp.200,000 ($AU30), depending on the event and the line up of DJs. Respondents told me that they spent anything from Rp.35,000 ($AU5) to Rp.300,000 ($AU40) for a night out.[81] Although the price of entry for clubs and events may be a deterrent for some young women, often the door men (i.e. bouncers) will wave-in (for free) Indonesian women they know. There are also an increasing number of clubs that advertise a 'girls' night out,' where girls can enter for free. It is also not uncommon for young women to find ways of getting in through a back door, being let in by their friends or bar staff, or by climbing over a wall or a fence. In the case of outdoor raves, many young people deliberately set off early in the day and spend the entire day on the beach, or cliff top location, so that they are already 'inside' when the pay or entry door is erected. Inside costs are minimal, as they share drinks or drink water, and allow others to buy drinks for them.

-

Once on the dance floor, Indonesian young women joget or ngedance (dance) with each other and with others who they usually do not know, men and women. The feeling among club or rave participants is that the more people on the dance floor the better. Part of the dugem experience is making new friends, and people are generally very friendly to each other on the dance floor. On a Saturday night (malam minggu), the dance floors become packed with dancing bodies, young (and not so young) men and women, gay and straight, Indonesian and foreign. Sometimes it is hard to move. The lighting is dark, with strobes and typical 'disco lights,' and in some clubs music videos are displayed on huge screens, or a catwalk is erected for a fashion show. As well as the DJs spinning their discs on a raised platform, thus performing to the crowd, there are also smaller podiums scattered through the dance floor for exhibitionists (men and women) to strut their stuff under the gaze of other clubbers.

-

The young women I met who were regularly participating in the party scene placed a strong emphasis on the sociability of clubbing, telling me that the dance parties enable them to 'socialise with friends'; 'to make new friends'; 'to enjoy' and feel young; to be 'free' and to 'release stress.'

I like the 66 (Nightclub), there are lots of friends here. I feel happy with my friends. Going home I feel I've had a good time, meeting new people. I love dugem.[82]

If I'm tired from work, I go out to entertain myself and to find new friends and a new atmosphere.[83]

I like going out and finding young leaves?my husband is already old and can't be invited out to have fun anymore. So I just go out. I'm bored at home too.[84]

I can meet people, meet old friends and new. We don't have to be worried and we can just be free and happy.[85]

It can be understood that the women go to dance parties to make friends, to dance and forget their troubles, to totally 'lose one self' and 'to forget everything for one night.' As one young woman who worked in a tourist hotel's salon said to me, 'I work hard and I want to party hard.'[86]

-

In direct contrast to Pini's research findings in the UK, where women 'dress to sweat' in unisex gear, which is seen as an important factor in the perceived erosion of sexual differences in the UK rave scene,[87] the girls in this study took full advantage of the opportunity to dress up and to be glamorous. Most young women enjoyed dressing up in sexy clothes, and the wearing of tight-fitting, Western-style clothes was in itself a challenge to traditional authority. Indonesian women are almost always far more dressed up than Western women at dance parties. However, the young women were able to construct themselves as sexy for themselves, partly because they could not express their sexuality in an open way in other areas of their lives, such as at their work, their home, or other social and public spaces. It did not necessarily mean that they wanted to have sex, however, and sex was not at the forefront of their minds when they were out. More important for them were social interactions, and then sex later, if they felt like it.

-

The dance party scene in Indonesia provides the female raver/clubber with an opportunity to experience fake glamour and Western-style dress (tight pants and skirts and tops and short dresses), and to dance and perform, showing the skill and beauty of their bodies. Some young women told me that they liked getting on the podiums in nightclubs when they were drunk or high on drugs, to dance and show off their bodies and sexy outfits. This kind of hyper-femininity is unheard of in Indonesian society where good girls do not go out at night wearing those types of clothes, and they certainly do not dance.[88] Young women told me about the extremes they would go to, to get ready for a night out, and how they would have to hide what they were wearing with long-sleeved tops and long skirts when they left their kampung (neighbourhood), until they got to the club or party. They also reported that the bouncers of some nightclubs would not let them in if they were dressed 'terlalu sexy' ('too sexy'), thinking that they were prostitutes. In these cases they would enter in their long-sleeved outfits and then disrobe in the bathroom, leaving their clothes for safe keeping with the cloakroom attendants. When it was time to go home they would make sure they covered up, especially if they went on a motorbike taxi.

-

Drugs that are most common in the Indonesian dance scene include ecstasy and shabu shabu (crystal methylamphetamine). Ecstasy is often brought in from overseas, but there are also many illegal 'factories' in Bali and Java.[90] Between 2001 and 2002, ecstasy was readily available in bars and clubs, with dealers operating openly. From 2003, however, the drug became less available and the price rose due to the government crack-down and 'War on Drugs,' spearheaded by Bali's new Chief of Police.[91]

-

Nearly all of the young women I spoke to who participated in the dance party scene had experienced taking ecstasy (which they called 'E') or shabu shabu and enjoyed taking it frequently. Others had tried cheaper, illegal prescription drugs which were available on the black market such as Ritolin, Xanax and OxyContin.[92] When I asked the women their reasons for drug use they said that, 'it feels great—when you are high it feels amazing' and 'when I'm high it's like I'm flying and I can dance all night.' The sensory and empathetic enhancements the drug offers to the experience of partying were clearly very important to the girls, as was the feeling of forgetting everything for one night. Some young women also expressed how they enjoyed feeling 'seperti anak' ('like a child') for a night, meaning they were carefree, with no feelings of responsibility. In addition, ecstasy and shabu shabu provided energy to help girls stay up all night dancing, particularly those who had to work or who had little sleep from partying all night the night before.

-

Some of the young women I spoke to, however, were not very interested in taking ecstasy or other drugs, and preferred to drink alcohol. As one 28-year-old woman who works in the woodcarving business put it:

I've tried E a few time but I couldn't enjoy it because I became confused and paranoid. So if I go out to the 66 or any other club I prefer to drink because drink makes me feel more confident to speak to new friends or boys. But only a bit drunk yeh?![93]

Other young women rarely took any drugs, and only did so if it was given to them by a friend, or they shared one pill between three or four of them, to make them 'trip'. This was mostly due to the cost which escalated significantly during the time of this research as a result of the concerted 'war on drugs.' Many girls stressed that they were still able to recapture the physical sensations and emotional states associated with previous encounters with ecstasy (what they called 'tripping') if they listened to the music and danced. This has been described by Melanie Takahashi, as a 'natural high' which rave participants can achieve through 'neural tuning' or 'flashbacks' at raves.[94]

-

For numerous reasons, rave has been described as a celebration of excitement and pleasure, creating a 'text of excitement,' which is common to many sub-cultures.[95] What is unique about rave when compared to other sub-cultures in Indonesia, however, is that girls are drawing on this excitement as much as boys. For this reason it may be understood as a site for new modes of femininity and physical pleasure for young women, providing a 'third space' for the expression of alternative identities, including sexual identities.

-

In her analysis of girls in the rave scene in the UK, Pini notes that rave can be seen as representing an important shift in sexual relations as 'it is one of the few spaces which afford—and indeed, encourage—open displays of physical pleasure and affection.'[96] This is especially important in Indonesia where displays of affection between those of the opposite sex are not acceptable anywhere in public (although same sex affection is very common). The essential point to note here, however, is that displays of sexuality and affection are not about sex, per se. This is because rave is often a 'non-phallic form of pleasure' for women, where the feeling is more sensual than sexual.[97] The reason for this is due to the consumption of ecstasy. As Nina (aged 32) told me, on the dance floor:

If I'm drunk I like to have mad ideas with my friends which we will do suddenly, like dancing sexily in front of guys, making them mad (with lust), but once I get high on pills my desire to have sex goes down.[98]

The feeling is similar for men, and it is this physical reaction to ecstasy which creates a safe, non-threatening and un-aggressive environment for women. This is because the ecstasy raises the oxytocin levels in male users, making them friendly but not predatory and putting them in a kind of post-orgasmic state, where 'they are not very good about performing sexually but they feel really good about the person they are with.'[99] For example, when I asked one 28 year old male, Arif, how he felt when he took ecstasy he said:

I feel happy, great, enjoying the feeling of freedom. My imagination flies far away. I feel energetic—'full power' [sic]. I like looking at people around me happy and dancing, to the loud music. I like sitting down to enjoy the E alone, and feel as though I am in love with the E. I don't have any sexual feelings if I am high on E.[100]

-

Such circumstances have created what has been described by Ben Malbon as the 'androgyny of the dance floor'[101] in rave or dance culture, which can be understood as a transformation of the sexual or marriage market, the 'meat' or 'cattle market' in the UK, or the ayam (chicken) market in Indonesia, towards an emphasis on socialising and dancing. As Malbon has noted, women are often attracted to arenas of intense social interaction. This is particularly true in Indonesia where the codes and demands of social interaction at raves and dance parties differ greatly from the hegemonic modes of social interaction in other social spaces, where women are confined to the parental or marital home, or the work/ office space. The use of ecstasy, therefore, results in men and women being content with dancing with each other and having fun. What the interviews also revealed, however, was a strong association between 'coming down' (turun) from E or alcohol, and wanting sex. Once the effects wore off, their libidos rose, and many women as well as men reported that they wanted sex and actively sought 'one night stands':

I prefer E if there is any! Because I feel joy and have lots of fun, I like dancing to loud music. Looking at people or being held by someone. If the feeling of high goes down, I want to have sex.[102]

If the feeling of being drunk subsides I like to make love. That's really great if there is someone to have sex with. I prefer alcohol![103]

If I'm with friends sometimes I take E but I often drink, but if I'm with friends, mmm? For sure I will take E because after the effects have worn off I can look for a room and 'that' (itu) (laughs)...I'm satisfied if there is a boy/ someone from the opposite sex.[104]

-

The young women I met reported that they had between one and four boyfriends a year and some had more than one boyfriend at one time, while many had experienced one night stands. As verbal communication is at a minimum at dance parties, and sensory perceptions are paramount, the language of 'hooking up' was unimportant. Young women told me about sexual encounters with Indonesian, Singaporean, Thai, Hong Kongese, Australian, German, Spanish, Italian, French, Brazilian and Japanese men, either for one night or longer. A few girls I spoke with were lesbian or bisexual, and found the dance party scene to be an accepting space to meet other women for one night or longer.

-

While these young women often chose Indonesian partners, many women appeared to have a penchant for Westerners, and there was certainly some status achieved in finding (and keeping) a Western boyfriend. One woman in her mid thirties told me that she preferred Western men as they allowed her more freedom, and that Indonesian boyfriends—even ones she had met out at nightclubs—were too controlling and would not let her dance or dress as she liked once she became their pacar (girlfriend).

-

The Javanese women seemed to be particularly adventurous in their sexual exploits. Such behaviour, in a place like Bali which is characterised by high numbers of transient transnational citizens, resonates with Katie Walsh's research with British expatriates in Dubai.[105] Walsh found that performances of sexual freedom can be closely associated with the geographies of being 'away from home,' because 'the imagined distance of being away from home increases the confidence of being able to take sexual risks.'[106]

-

In spite of their risky behaviour (wearing provocative clothing, taking drugs, drinking and having sex with strangers), it was clear to me that that women who participate in the dance party scene in Bali felt safer and more comfortable than in most other nocturnal social situations in Bali, particularly traditional pubs or bars. Nightclubs were considered safer. As Dewi (26) said to me: 'I always feel safe. I've been coming here (66 Nightclub) for three years and I've always felt safe until now.'[107] However, other women I spoke to were acutely aware of the potential risks of being out at night, but were prepared to take the risk as the returns of a good night out were too good to miss: 'You never know what may happen, it could be safe or it may not be safe. Yeah, that's the risk you take going out at night.'[108]

-

After 2003 there was also the increased risk of being arrested for illegal drug-related behaviour, due to the crack-down on ecstasy producers, dealers and users, and this was reflected by the increased numbers of people in prison on drug-related charges.[109] Related to this was a strong sense that things were not as safe as they used to be on the dance floor. One young man told me how he believed incidents of nocturnal violence had increased as a result of the drug crack-down. This was because people were drinking more heavily instead of taking ecstasy, and alcohol consumption made them more violent. Mostly, however, the young women I spoke to talked about feeling 'free' from worries when they were at dance parties: 'we don't have to feel worried, we can be free and happy.' A few of the respondents also told me that they were happy to go to a club or event on their own, as they were sure that they would meet up with friends, or make new ones, once they were there. This is unusual in Indonesian society, where it is almost impossible to go anywhere alone, and young women in particular always 'ikut' (accompany) each other everywhere, especially at night.

-

Alison Murray has commented, when writing about perek (perempuan eksperimental)[110] in Jakarta, that women who adopt various forms of commodified rebellious behaviour are opposing the dominant discourse and as such are members of a sub-culture. She further asserts that they have an 'ambivalent relation to the wider society, in that they both reject authority and embrace aspects of spectacular consumption in the creation of style.'[111] Following Alsion Murray, I see that the objections young women have towards the hegemonic culture in Indonesia have found new expression

|

|

through their participation in the rave scene. The challenge to hegemony is not issued directly, however, but rather it is expressed 'obliquely in style and behaviour.'[112] The young women involved in the rave sub-culture question mainstream ideologies and bring forth alternative femininities and sexual identities, but not in the same way as the perek who explicitly used their sexuality to object in public. The rave sub-culture, then, allows young women in Indonesia to 'let their hair down' by creating an avenue of expression which has never been available to them before in public. And their participation in the dance party culture is heavily influenced by their global ideas of modernity, individuality, freedom and youth life style.[113]. The poster shown in Figure 2, with the title 'Merdeka Rave' (Rave Freedom), clearly illustrates the perceived connection between rave and liberation for young women in the Indonesian dance party scene.

Figure 2. Merdeka Rave ('Rave Freedom'). Photo from 'Merdeka Rave,' in Outie.Net, online: http://outie.net/forums/attach/7227990615043l.jpg, accessed 16 June 2008.

|

Conclusion

-

In this paper I have explored how young women participating in the dance party scene in Bali, Indonesia actively resist subordination by adopting specific tactics and geographies of resistance, by negotiating the sub-culture to produce their own gendered sense of place in nocturnal spaces. The rave scene, therefore, creates a space for female participants to be released from societal constraints and to loose their inhibitions for one night. This feeling is no better described than in the anonymous, 'Ravers Manifesto', which speaks for ravers everywhere:

In these makeshift spaces, we seek to shed ourselves of the burden of uncertainty for a future you have been unable to stabilize and secure for us. We seek to relinquish our inhibitions, and free ourselves from the shackles and restraints you've put on us for your own peace of mind.[114]

-

Once in the dance party space, young women are able to enjoy the codes and demands of social interaction which differ greatly from those in other Indonesian social spaces. First and foremost, is a focus on and desire to dance and to interact with the crowd. The loud music leads to considerable difficulty in verbal communication, while the presence of ecstasy makes them want to dance and suppresses libido: 'The 'underlying codes of interaction are quite different (to being in a bar) and this difference appears to be attractive to women.'[115]

-

The rave scene in Bali is a place where young women can construct and experiment with new femininities, while simultaneously challenging dominant society's expectations of how a 'good girl' should behave in Indonesia—by dressing in sexy clothes, displaying tattoos, dancing in a provocative way, drinking alcohol, smoking, taking drugs and having (or not having) sex, and by saying that they 'don't care' about rules or how society perceives them.[116] It is in this way that these young women have managed to create their own gendered cultural spaces and alternative identities within specific nocturnal places, which they use as sites of autonomy and resistance to the dominant, patriarchal forces in society. I see these processes as overwhelmingly empowering for the majority of women involved. This is because the dance party scene in Bali is characterised by a sense of self expression where women are able to dance without the same threat of violence as found in traditional discos, and where they have more freedom to dance with and talk to whoever they like. These women have seized control of the nocturnal space and have negotiated their femininities by participating in traditionally masculine activities. These behaviour patterns, as well as dressing and dancing overtly 'sexy,' can all be seen as an act of 'refusal' of the conventional notions of femininity in dominant discourse.[117]

-

Young women in the dance party scene in Bali attempt to subvert patriarchal ideology by rejecting the sexist label ayam given to them by mainstream society, and by identifying themselves as the same as young men when they are at clubs and dance parties. This resistance is achieved through their patronage of dugem and specific nocturnal sites which are created through the correct combination of electronic dance music, the consumption of the drug ecstasy, and dancing crowds. These chemical landscapes provide a 'third space' for young women,[118] in which they can feel safe to dance, socialise and experiment with alternative identities.[119] Simultaneously, while dancing, the young women are also 'debating, contesting and subverting the socially constructed gender roles and relations' and the ideological constructions of space.[120] This is achieved by refusing the dominant notions of femininity and participating in the spectacle of rave sub-culture, by seeking visible identities and styles which defy mainstream respectabilities and are aligned with Western consumerism.

-

There are also spatio-temporal geographies of resistance involved in their day and night time activities, as the young women negotiate a different production and use of space. Their identities are fluid and shifting, depending on whether they are dancing at night or working during the day. The girls with whom I spent my time had attached themselves to particular nightclubs, thus creating a positive self-identity for themselves. The night clubs and rave parties are sites of liberation for the young women, where they can dress and act as they like, because it is their own space, a place that gives them a feeling of belonging, and where they feel relatively safe. In addition to this place attachment, the young women experience a wide variety of spatial relations over a number of different social sites, including bars, other nightclubs, 'after parties' at private villas, and organised raves. In the day time they are much more restricted in their mobility and usually spend their time at work or university, in the warnet (internet shop) or eating in a warung (food stall). At these times they wear conservative clothes and adopt a more modest manner in public.

-

Finally, this research points to questions of sexuality and pleasure for young Indonesian women at clubs and 'raves,' and exposes an important shift in sexual relations in Indonesia, with rave culture's emphasis on dance, physicality and affection. In the past such challenges to hegemony and blatant flaunting of acceptable modes of behaviour have resulted in the closing-down and banning of subversive 'rave dens,' such as discos and nightclubs. Recently there has been news from Bali that the authorities are seeking to change the laws on club opening times, and to enforce a 3 a.m. close on all venues and dance parties, in an attempt to put an end to the all-night dance parties that are now commonplace. This would indeed change Bali's nightscapes.

Endnotes

[*] I would like to thank the young women in the Indonesian dance party scene for assisting me in this research. The research was made possible through the support of the Department of Geography, Royal Holloway College, University London and through a staff research grant from the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at the University of Queensland. Special thanks also to Lyn Parker, Linda Bennett, Kabita Chakraborty and my two anonymous reviewers for the extremely helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. Of course, any shortcomings in the paper are solely my responsibility, and should not be attributed to anyone else.

[1] Dugem, short for Dunia gemerlap, translates as 'the glittering world,' referring to the lights at a club or rave party.

[2] See Shirlena Huang and Brenda Yeoh, 'Heterosexualities and the global(ising) city in Asia: introduction,' in Asian Studies Review, March, vol. 32 (2008):1–6, p. 1.

[3] Huang and Yeoh, 'Heterosexualities and the global(ising) city in Asia,' p. 1.

[4] See Steve Pile and Michael Keith, 'Introduction' in Geographies of Resistance, ed. S. Pile and M. Keith, London, Routledge, 1997, pp. 1–32; and Harriot Beazley, '"Vagrants wearing makeup": negotiating space on the streets of Yogyakarta, Indonesia,' in Urban Studies, vol. 39, no. 9 (2002):1665–687.

[5] See Beazley '"Vagrants wearing makeup,"' p. 1665; Linda Bennett, Maidenhood, Islam and Modernity: Single Women, Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Contemporary Indonesia. London: Routledge, 2005; Julia Suryakusuma Sex, Power and Nation: An Aanthology of Writings, 1979–2003, Jakarta: Metafor Publishing, 2004.

[6] Fieldwork was conducted between 2001 and 2006 for a period of sixteen months in Seminyak and Kuta, Bali. I am grateful to Royal Holloway College, University of London, for supporting the initial stages of this research, and to the University of Queensland for the funding of the latter stage of the research (2005–2006) through the provision of a UQ New Staff research grant.

[7] As well as ethnographic fieldwork, an analysis of Indonesian blogs, websites and chat rooms was conducted, focusing on discussions about clubbing, night life and rave dance parties. See for example INDAHNESIA.com: Discover Indonesia Online, 2002-2008, online: http://indahnesia.com, accessed 6 June 2008; RVLX5 2003–2008, (The Indonesian Ravers and Electronic Dance Music Network), online, http://ravelex.net/, accessed 16 June 20008. Flyers for raves and parties were also collected, and the bi-weekly Beat Magazine (A Partier's Guide to Bali), a free, locally-produced magazine in English and Indonesian for 'nightlife professionals,' with coverage on recent dance party events and promotions of up and coming events in Bali and Jakarta, as well as articles on culture, fashion and nightlife (also available online at http://www.beatmag.com).

[8] Stuart Hall & Tony Jefferson (eds), Resistance through Rituals: Youth sub-cultures in post-war Britain, London: Routledge, 1976; Dick Hebdige, Sub-culture: The Meaning of Style, London, Methuen & Co Ltd, 1979; David Muggleton, Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style, Oxford, Berg, 1997; Vered Amit-Talai and Helena Wulff (eds), Youth Cultures: A Cross-Cultural Perspective, London: Routledge, 1995.

[9] K. Robinson, and S. Bessell (eds), Women in Indonesia: Gender, Equity and Development, Singapore: ISEAS Press, 2002; L. Sears (ed.), Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, London: Duke University Press, 1996; Bennett, Maidenhood, Islam and Modernity; Suryakusuma, Sex, Power and Nation.

[10] Pile and Keith, Geographies of Resistance, pp. 1–32.

[11] Hall and Jefferson, Resistance through Rituals; Hebdige, Subculture.

[12] Angela McRobbie and Jenny Garber, 'Girls and sub-cultures: an exploration,' in Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Sub-cultures in post-war Britain, ed. Hall and Jefferson, London: Routledge, 1976, pp. 209–22; Angela McRobbie and Mica Nava (eds), Gender and Generation, London: Macmillan, 1984.

[13] Doreen Massey, 'The spatial construction of youth cultures,' in Cool Places: Geographies of Youth Cultures, ed. Tracey Skelton & Gill Valentine, London: Routledge, 1998, pp. 121–29.

[14] See for example Muggleton, Inside Subculture.

[15] My ambivalence about using the word 'sub-culture' is because of the nuances between 'rave' or EDMC, which I see as a sub-culture, and 'club culture,' which is always on the verge of becoming mainstream youth culture due to the appropriation of EDMC by global businesses such as the well known 'superclub' The Ministry of Sound (MoS), which has clubs in London, Sydney, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and New Delhi. The balance between being a youth culture and a youth sub-culture is, therefore, always being negotiated depending on the location of the event, who has organised it, and the individuals who participate in it.

[16] See for example, Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999; Ben Malbon, Clubbing: Dancing, Ecstasy and Vitality, London: Routledge, 1999; Steve Redhead (ed.), The Clubcultures Reader: Readings in Popular Cultural Studies, Oxford: Blackwell, 1987; John Chatterton and Mike Holland, Urban Nightscapes: Youth Cultures, Pleasure, Spaces and Corporate Power, London: Routledge, 2003; John Connell and Chris Gibson, Soundtracks: Popular Music, Identity and Place, London: Routledge, 2002; Rave Culture and Religion, ed. Graeme St John, London: Routledge, 2004; Brian Wilson, Fight, Flight, or Chill: Sub-cultures, Youth and Rave into the Twenty-First Century, London: McGill Queen's University Press, 2006.

In the past decade the Hip Hop sub-culture has become popular globally, particularly among black and white marginalised youth in developed and developing countries, but has taken on its own local form wherever it has travelled, from New York to the Australian bush. See Tony Mitchell's Australian Research Council (ARC) funded project, Local Noise on the internationalisation of hip hop and the localisation of hip-hop in different cultural, and societal contexts, URL: http://www.localnoise.net.au/, accessed 15 March 2008. Also see Tony Mitchell, 'Blackfellas rapping, breaking and writing: a short history of Aboriginal hip hop,' in Aboriginal History, vol. 30, (2006):124–27.

[17] See Maria Pini, 'Women and the early British rave scene,' in Back to Reality? Social Experience and cultural studies, ed. Angela McRobbie, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997, pp. 152–70; Maria Pini, Club Cultures and Female Subjectivity: The Move from Home to House, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001; Fiona Hutton, Risky Pleasures? Club Cultures and Feminine Identities, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006.

[18] There are, however, a number of studies focussing on foreign tourists and other Westerners participating in the Goa Trance scene in India, and at the 'full moon' rave parties in Koh Phangan, Thailand. See Arun Saldanha on the rave scene in Goa: 'Goa trance and trance in Goa: smooth striations,' in Rave Culture and Religion, ed. Graeme St John, London: Routledge, 2004, pp. 256–72; Anthony D'Andrea, 'Global nomads: techno and new age as transnational countercultures in Ibiza and Goa,' in Rave Culture and Religion, ed. G. St John, London: Routledge, 2004, pp. 236–55; and Klaus Westerhausen, Beyond the Beach: An Ethnography of Modern Travellers in Asia, Bangkok: White Lotus, 2002, for an analysis of Westerners participating in the rave scene in Koh Phangan, Thailand. To date there are no studies that examine indigenous ravers within these or any other sites, although Saldanha presents an interesting analysis of race issues that emerge between Indian ravers, white tourists and white 'locals' at Goa trance parties. See Arun Saldanha, 'Goa trance and the viscosity of race,' in ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies. vol. 4, no. 2 (2001):172–93). See also Arun Saldanha, 'Music, space, identity: geographies of youth culture in Bangalore,' in Cultural Studies, vol. 16, no. 3 (2002):337–50.

[19] McRobbie and Garber, 'Girls and Subcultures'; Anita Harris, Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century, New York and London: Routledge, 2004.

[20] See McRobbie and Nava's edited volume, Gender and Generation.

[21] Kerry Carrington, 'Cultural studies, youth culture and delinquency,' in Youth Subcultures: Theory, History and the Australian Experience, ed. Rob White, Melbourne: National Clearing House for Youth Studies, 1993, pp. 27–32, p. 30.

[22] Angela McRobbie (ed.), Feminism and Youth Culture: From 'Jackie' to 'Just Seventeen, Boston, Unwin Hyman, 1991, p. 25.

[23] See for example, Huge Matthews, Mark Taylor, Barry Percy-Smith and Melanie Limb, 'The unacceptable flaneur: the shopping mall as a teenage hangout" in Childhood 7, no. 3 (November 2003):279–74; Tracey Skelton, 'Nothing to do, nowhere to go: teenage girls and ?public space" in the Rhondda Valleys, South Wales,' in Children's Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning, ed. Sarah Holloway and Gill Valentine, London, Routledge, 2000, pp. 80–99.

[24] Skelton, 'Nothing to do, nowhere to go,' p. 80.

[25] Pini, Club Cultures and Female Subjectivity; Hutton, Risky Pleasures; Malbon, Clubbing.

[26] Pini, 'Women and the early British rave scene.'

[27] Beazley, '"Vagrants wearing makeup."'

[28] Pile and Keith, Geographies of Resistance, pp. 1–32.

[29] Alison Murray, No Money No Honey: A Study of Street Traders and Prostitutes in Jakarta, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

[30] See Barbara Hatley, 'Subverting the stereotypes: women performers contest gender images, old and new,' in Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, vol. 41, no. 2 (2007):173–204; and Helen Creese, 'Reading the Bali Post: Women and Representation in Post-Suharto Bali,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, 10, August 2004, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue10/creese.htm, accessed 6 July 2008.

[31] Suryakusuma, Sex Power and Nation.

[32] Creese, 'Reading the Bali Post,' para. 1.

[33] Hatley 'Subverting the stereotypes,' pp. 173–77.

[34] Sonja van Wichelen, 'Reconstructing Muslimness: new bodies in urban Indonesia,' in Geographies of Muslim Identities: Diaspora, Gender and Belonging, ed. Cara Aitchison, Mei Po Kwan, and Peter Hopkins, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007, pp. 93–108, p. 100.

[35] Van Wichelen, 'Reconstructing Muslimness,' p. 100.

[36] Van Wichelen, 'Reconstructing Muslimness,' p. 100.

[37] For example, the fall of Suharto led to a freer press and increased exposure to sex videos, magazines and tabloids. This in turn caused a backlash by key Muslim figures and the attempt to push through parliament the 'anti-pornography law.' See Hatley, 'Subverting the stereotypes,' pp. 174–75. The law would outlaw erotic dancing, public kissing or displays of affection and would forbid women to expose 'sensual body parts,' which would include the hair and from the neck to the ankles. Theoretically, the new law could mean that young women sunning on the beaches or dancing in the clubs of Bali could be arrested.

[38] See Pamela Allen and Carmencita Palermo 'Ajeg Bali: multiple meanings, diverse agendas,' in Indonesia and the Malay World, vol. 33, no. 97 (2005):239–55; and Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, Women in Indonesia.

39 Creese, 'Reading the Bali Post,' para. 2.

[40] Pam Allen describes ajeg Bali as the 'siege mentality' of 'fortress Bali' which has 'hardened' since the second Bali bombing in October 2005. See Pam Allen, 'Paradise on earth: the enigmatic island,' in Famous Reporter, no. 35, (undated) URL: http://walleahpress.com.au/FR35Allen.html, accessed 30 April 2008.

[41] Creese, 'Reading the Bali Post,' para. 8.

[42] See St John, Rave Culture and Religion, p. 2. A 'doof' is a type of outdoor dance party in Australia, generally held in a remote area and similar to a rave, but with political connotations. The term 'doofing' refers to the repetitive drum-beat that sounds like doof, doof, doof. Doof can be used to describe the music, the event at which it gets played, or the dance that happens there. Doof-goers are mainly alternative crowds, comprised of environmental activists, peace activists or 'hippies.' See St John, Rave Culture and Religion, p. 2.

[43] St John, Rave Culture and Religion, p. 2.

[44] In the UK, USA and Australia, raves or dance parties have traditionally taken place in a warehouse, open field, the desert (Australia) or dance club. In the developing world, however, they are known for taking place in exotic locations such as on a beach, on cliff tops, in a forest or valley, or up a mountain.

[45] Ecstasy is a drug that is chemically related to amphetamine and mescaline and is used illicitly for its euphoric and hallucinogenic effects.

[46] Oxytocin is a hormone produced naturally in the hypothalamus area of the brain. It regulates a variety of physiological processes, including emotion. See M. Kosfeld, M. Henrichs, P. Zak, U. Fischbacher and E. Fehr, 'Oxytocin increases trust in humans,' in Nature, vol. 435, (June 2005):673–76.

[47] Wilson, 'Fight, flight or chill,' p. 16.

[48] Graeme St John, 'Youth dance cultures, doofs & alternative spiritualities: short summary notes as a basis for missional reflection and action,' in The Challenge to Christians in a Postmodern World to Meet New Religious Spiritualities and Non-Religious Spirituality, Thailand: Lausanne Forum, 2004, URL: http://www.areopagos.dk/lausanne/Youth%20Spirituality%20in%20Rave%20Dance%20Cultures.doc, accessed 23 March, 2007.

[49] St John, 'Youth dance cultures, doofs and alternative spiritualities.'

[50] The Acid House Movement and the Summer of Love emerged in part as a rejection by British youth to the oppression of the Thatcher years, which through its repressive and punitive laws created a fragmented and disparate society.

[51] St John, Rave Culture and Religion; Connell and Gibson, Soundtracks.

[52] For an exception see Saldanha, 'Music, space, identity'; and Saldanha, 'Goa trance and the viscosity of race.'

[53] St John, Rave Culture and Religion, p. 2.

[54] Connell and Gibson, Soundtracks, p. 229.

[55] Marisa Duma, 'Indonesia's dance culture: the society's scapegoat?,' in Journal by the Lightbeamers, MD: Anthology of Commentary Articles, April 2007, online: http://journal.marisaduma.net/2007/04/30/indonesias-dance-culture-the-societys-scapegoat/, accessed 20 June 2008.

[56] I observed a number of these ecstasy raids (Razia Ecstasy) take place on nightclubs in Jakarta and Yogyakarta during fieldwork for my PhD on street children and youth in the years of 1995, 1996 and 1997. Usually a razia consisted of up to thirty riot police storming nightclubs and searching people for drugs. These days the raids are more technologically advanced and include on-the-spot urine tests of rave participants for ecstasy and other drugs.