Half Mountain – Half Sea:

Women's Roles in the Fishing Communities of Post-War Kaohsiung,

1945–1975

半山半海:

婦女在高雄漁村中所扮演的角色, 1945–1975

Chen Ta-Yuan 陳大元

Introduction

-

The maritime history of Taiwan has not been considered an important research topic in academia thus far. Historians who work on Taiwan-related topics are much keener to look at the history of Taiwan's politics, international relations or economic development. Only a few historians have conducted research on Taiwan's fishing communities; however, they simply focus on male fishers, and describe the livelihoods of the residents of fishing villages from the perspective of economic geography. In research on the topic to date, historians have not mentioned much about the roles of women, who comprised half of the total population of Taiwan's fishing communities and who contributed logistically to the fishing activities. The purpose of this paper, then, is to explore the activities of the female family members onshore, and what kind of family problems occurred when fishers worked for extended periods at sea. In this paper, I will argue that women made substantial contributions to the development of Taiwan's fishing industries. Similar research on the women's lives in the fishing villages has been done in Japan and the United Kingdom and therefore the Taiwanese case is important for a comparative study in future.

-

I limit the geographic scope of my research on Taiwan to Kaohsiung Fishing Port, because Kaohsiung is the centre of Taiwan's fishing industries (see Map 1). At the same time, for the following two reasons I limit the temporal range of my study to two significant moments in regional time, namely the years between 1945 and 1975. Firstly, it was in 1945 that World War II ended and Taiwan's fishing industries started to recover from wartime devastation; secondly, in the mid-1970s, onshore economic activities in the metropolitan areas created plenty of employment opportunities, which indirectly encouraged numerous young fishers to quit their fishing careers. Thus, the fishing communities in Kaohsiung gradually began to die out.

-

There are two methodological approaches used in this study: oral history and anthropological fieldwork. A large number of older women still reside in the Kaohsiung Fishing Port. However, most of them are illiterate and unable to write down their past and present ways of life. The literature relating to their lives and histories, as a result, is extremely limited. In order to collect oral histories and to experience the rhythm of their lives, I stayed in Gushan District, the cradle of the Taiwan fishing industry in Southeast Asia, from December 2001 to July 2002 and from January to February 2003.[1]

-

Initially, I had difficulties in interviewing the female relatives of fishers in these conservative and patriarchal fishing communities. However, with help from locals, I gradually earned their trust and successively built up a small social network. Even so, because I am an unmarried male and girls and women are considered the property of their husbands and fathers it was impossible for me to interview the female relatives of fishers alone. There was always at least one male member of the family present. Consequently, the questions I was able to ask the women were always influenced by the presence of these male relatives. Sometimes, however, the information I collected was incidental to the original purpose of the interview with one or other female relative interrupting and having her say to a question I had asked the male relative.

-

Also, I need to make something clear here so as not to be accused of insensitivity. In Taiwan it is culturally prohibited for a young man to ask an old woman's name, especially before her husband. Hence, the names of the old fishers' wives remain unknown and throughout the paper I can, unfortunately, refer to them only as 'the wife of A' or 'the female relative of B'.

-

The outline of this paper is as follows. Initially I explore the socio-economic background of the area, before turning my attention to the women's onshore economic activities in the Kaohsiung fishing communities. I look at such things as the production and maintenance of fishing gear, aquaculture activities, commercial activities in Gushan district, women's role in financial matters. In the second part of the paper I explore women's social status, marriage and family problems associated with extramarital affairs and gambling.

Map 1. Geographical location of Kaohsiung City.

Map produced by Chen, Ta-Yuan.

Map 1. Geographical location of Kaohsiung City.

Map produced by Chen, Ta-Yuan.

|

Socio-Economic Background

-

Kaohsiung fishing communities include three different ethnic groups: the local Taiwanese of Kaohsiung, Penghuans, and people from Siao Liouciou. In order to seek a better life, the latter two groups migrated from their barren home areas of Penghu and Siao Liouciou (see Map 2) to Kaohsiung, the second biggest city of Taiwan.

-

The Penghu Islands comprise several tiny and impoverished islands off the southwest coast of Taiwan. Traditionally, women and children remained onshore and worked the excessively dry land which could only grow peanuts, sorghum, sweet potatoes, sponge gourds and aloes. The lack of agricultural productivity and sustainable natural resources drove Penghuan men to make a living on the sea. Hence, in terms of the gender division of labour, men worked at sea; women worked on shore. Such a cultural-ecological pattern and way of life was called by the Penghuans, 'half mountain; half sea'.[2]

-

The economically depressed situation in Siao Liouciou was worse than in Penghu. The shape of the island of Siao Liouciou is like a shoe, and it is also extremely tiny. From the northeast to southwest the island is about 4.1 kilometres long; and from the northwest to southeast it is just 2 kilometres wide. The surface of the island is covered by limestone and deposits of coral sand which cannot sustain viable agricultural activities. Hence, men in Siao Liouciou were also forced to make a living at sea, or to seek fisheries jobs in Kaohsiung, as some of the Penghuan islanders did.[3]

Map 2. Penghuan and Siao Lioucious' fishing migration.

Map produced by Chen, Ta-Yuan

Map 2. Penghuan and Siao Lioucious' fishing migration.

Map produced by Chen, Ta-Yuan

|

-

The rapid growth of the Kaohsiung fishing industries after the end of World War II encouraged Penghuan and Siao Liouciou fishers to settle down in Kaohsiung.[4] The Penghuans constituted the main source of labour in the distant water fisheries. They generally served as employees on fishing vessels and only a few of them have ever started their own fishing companies. Most of the fishers from Siao Liouciou have remained in the offshore longline fishing industry. They invariably started their fishing careers with offshore longlining in the waters off Siao Liouciou, and gradually extended their fishing grounds into Southeast Asian waters. The local Taiwanese of Kaohsiung never stuck to any particular fishing method.

Women's onshore economic activities in the Kaohsiung fishing communities

-

When fishers were working at sea, what kind of fisheries-related activities did their female family members undertake in the Kaohsiung fishing communities? Different types of activities existed in different districts. Cijin district, however, was a less developed and prosperous area. Most women living in the fishing villages were engaged in coastal fisheries and fisheries-related activities. The manufacture and maintenance of fishing nets or longlines, and aquaculture activities, such as collecting milk fish and preparing oysters, occupied most of their time.

-

In the early years, fishing nets and lines produced by factories were too expensive for many fishing families. To save on the expenditures of offshore fishing activities some women in the Cijin fishing communities traditionally made fishing nets or longlines for neighbouring villagers. The fishing nets they produced were small and could be used only for the coastal and offshore fisheries.[5] Traditionally, fishing nets and longlines were made from bark thread; some were also woven from cotton yarn.[6] People in the fishing villages had to buy bark at the local shop, and then manufacture nets or longlines on vacant lots in their village. My informant, the wife of Chen Shuteng, explained that making bark thread required two steps: first, the bark had to be soaked in water. After it turned soft it was torn into strips. Second, the strips needed to be exposed to the sun until they dried, after which the strips were twisted into strings. The whole process of making the thread and weaving a net was complicated and time-consuming, because the strings broke all the time.[7] Normally, women in the fishing communities took charge of this task, because it was not too physically demanding but it required patience, which, according to a female relative of Cai Bian, not many men possessed.[8]

-

In the 1950s, fishing nets and longlines made from bark thread gradually were replaced by factory-made cotton fishing nets and longlines. Cotton-made nets and longlines were sold in fishing tackle shops at reasonable prices which every fishing family could afford. Hence, women in Taiwanese fishing communities were eventually liberated from the burden of making bark thread and nets.[9]

-

Neither locally made nor factory-made fishing nets and longlines could be used for a long period of time. They easily rotted or tore in the salt water. To lengthen the use-by date of nets made from either bark or cotton, people in fishing communities had to spend a lot of time on the maintenance of these fishing nets and longlines. Some women were hired to do this arduous but important work; however, the money they earned was very little and never enough to help cover the overall family expenses.[10]

-

Apart from darning fishing nets every day, women also had to clean and add a protective coating on the fishing nets and longlines at least once a week. The protection of the fibre in fishing nets and longlines was an extremely laborious job that required the cooperation of both sexes in the fishing communities. Women took charge of extracting the starch from red potatoes. They grated red potatoes on a wooden board embedded with nails, then they mixed the potato paste with some water, before immersing the fishing nets and longlines into the extracted starch mixture. The fishing nets and longlines were then hung out on racks and exposed to the sun until the starch was totally dry. During this period, the people in the fishing village also had to collect pigs' blood from the pig farms, dry it, and then grind it into a blood red powder. The women would mix the blood powder with some water and immerse the fishing nets and longlines once again—to provide yet another layer of protection from the sea water.[11]

Figure 1. Fishing nets and longlines were traditionally made from bark thread; some were also woven from cotton yarn. These early nets and lines tended to rot in water over time; therefore, the inhabitants of Taiwanese distant water fishing communities needed to spend a lot of time on maintaining and mending fishing nets and longlines. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

Figure 1. Fishing nets and longlines were traditionally made from bark thread; some were also woven from cotton yarn. These early nets and lines tended to rot in water over time; therefore, the inhabitants of Taiwanese distant water fishing communities needed to spend a lot of time on maintaining and mending fishing nets and longlines. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

|

-

Then, the dyed fishing nets or longlines were put into a huge cauldron under which was a large steamer. They heated the steamer until the fishing nets and longlines were totally boiled by the steam. This traditional approach was handed down in the fishing communities from one generation to the next. Until the mid 1950s, women had to do this job every week; otherwise the fishing nets or longlines would fray and become useless after only ten days of fishing operations.[12]

-

Concerning the protection of longlines, besides red potato juice there were two other natural materials that could be used: egg white and mineral pitch. Traditionally, people placed the longlines in a wooden basin filled with egg white and then rubbed the egg white thoroughly through the longlines—covering the line with a protective layer of albumin. Then they wound the longlines onto wooden spools, and exposed them to the sun to dry. The dried longlines were then also put into a cauldron and steamed.[13]

-

Maintaining the longlines with a coating of egg white was a costly process because eggs were extremely expensive in those days. However, that was a fortunate time for the children in the fishing communities, because they had the leftover egg yolk as a regular part of their diet.

-

However, since the 1960s, nylon yarn has gradually been used throughout the fishing industry.[14] Thus, women in the Taiwanese fishing communities were no longer required to spend so much time on the maintenance of fishing nets and longlines. The introduction of nylon fishing nets and longlines, to some extent, changed the traditional outlook and employment opportunities for women of the fishing communities of Kaohsiung.

Figure 2. Since the 1960s, nylon line has gradually been introduced throughout the Taiwanese fishing industry. The photograph shows a woman and child preparing nylon fishing nets and gear at home. The photograph signifies the important onshore role that women played in terms of the gender division of labour in Taiwanese distant water fishing communities. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

Figure 2. Since the 1960s, nylon line has gradually been introduced throughout the Taiwanese fishing industry. The photograph shows a woman and child preparing nylon fishing nets and gear at home. The photograph signifies the important onshore role that women played in terms of the gender division of labour in Taiwanese distant water fishing communities. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

|

-

As well as doing all the net and longline maintenance and protection, the women also played a very important role in Kaohsiung's aquaculture activities related to oyster farms and milk fish. There were numerous oyster farms along the beaches of Cijin District before the ports and harbours were renovated. Those oyster farms created many job opportunities for women in the fishing communities. Before oysters could be cultivated in oyster beds, the farmers first had to have poles fixed on the seabed, so that seed oysters could be hung on the poles and then cultivated. Some local women were hired to work on bamboo rafts from which they handed the special poles to divers working in the water. Divers took five or six bamboo poles with them on each descent, and would not emerge from the water until all the poles had been securely fixed on the seabed in an orderly manner. Oysters would then have to be harvested before the advent of the typhoon season. A large numbers of divers were Penghuan men, because local people believed that Penghuan migrants could stay under water for a longer period of time.[15]

-

Women in the fishing communities were kept busy shucking oysters, which were one of the important ingredients for making zongzi (traditional pyramid-shaped rice dumplings). In order to preserve the oysters for a long period of time, the women had to spread them out in the sunlight and rotate them regularly until they were completely dried. Pedlars would then come to the villages to collect the dried oysters at regular intervals, because, for the annual Dragon Boat Festival, held on the fifth day of the fifth month of every lunar year, there would be a huge demand for pyramid-shaped rice dumplings with its special ingredient, dried oysters.[16]

Figure 3. A common scene of women in the Cijin District busy shucking oysters. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

Figure 3. A common scene of women in the Cijin District busy shucking oysters. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

|

-

Women in the fishing communities were also kept busy collecting baby milk fish two weeks prior to the annual Tomb Sweeping Day (around April 5 or 6). They waded into the water and used small nets to collect the tiny fish. How many they could collect depended on the weather. Usually they could anticipate a better catch in the season of the south wind. Milk fish collectors then came to each village to collect the special catch. One woman might earn between $NT100 and $NT200 in a single day, which was considered an extraordinary sum of money at that time. Women were eager to do this job because the money they earned would greatly contribute to their household income.[17] At that time of the year, even some of the male fishers, mainly coastal and offshore fishers in the Cijin area, stopped their regular fishing activities at sea and concentrated solely on milk fish collection—particularly during the typhoon season.[18] At this time, milk fish collection was safer and more lucrative than their other fishing duties on board vessels. The women in the fishing communities worked on milk fish collection until the advent of White Dew (around September 8), because both the quantity and quality of the tiny fish gradually decreased after the time of the White Dew.[19]

-

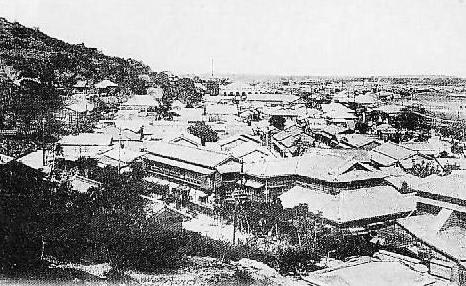

Apart from net maintenance, oyster shucking or milk fish gathering, the female relatives of fishers could work in the Gushan district, which had been urbanised since the colonial era (see Image 4), and it served not only as a distant water fisheries centre, but also as a hub of local commerce. The distant water longline and trawl fisheries of Gushan required more professional behind-the-scenes service, which prevented the fishers' family members from getting directly involved in such technical and maintenance activities. Most fishers' families lived in apartments or in the narrow alleys of urban districts, and regularly mingled with people engaged in onshore business activity (see Image 5). Thus, their economic activities were not necessarily associated directly with the fishing industry. The female relatives of the fishers, living in flats, could work for processing factories, restaurants, run a stationery shop or a grocery store, or work as stall-keepers, or housemaids for the rich. My informant, Chen Shuteng's wife, said that a large number of the daughters of Penghuan fishers worked as domestics after they moved to Gushan.[20] In the late 1950s, poor people in Gushan fishing port still treated longlines for vessel owners or fishing companies in exchange for free fish; however, this practice disappeared in the 1960s.[21]

Figure 4. An early photograph of Gushan District showing that it had been urbanised since the colonial period. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

Figure 4. An early photograph of Gushan District showing that it had been urbanised since the colonial period. Source: Kaohsiung City Fisher Service Association.

Figure 5. Gushan Fishing Port in the twenty-first century. Nowadays, the port of Gushan is noisy, dirty and extremely crowded. However, it does not mean that accommodation is necessarily cheap. While conducting my fieldwork near the dockside, it cost me $NT7000 ($AU350) per month to rent just a single room. Photographed by Chen, Ta-Yuan

Figure 5. Gushan Fishing Port in the twenty-first century. Nowadays, the port of Gushan is noisy, dirty and extremely crowded. However, it does not mean that accommodation is necessarily cheap. While conducting my fieldwork near the dockside, it cost me $NT7000 ($AU350) per month to rent just a single room. Photographed by Chen, Ta-Yuan

|

-

Post-war fish processing factories in Gushan District also created a lot of job opportunities for women in the fishing communities. The female relatives of fishers were hired to shuck shrimps caught by offshore trawlers. The shrimps they shucked would be processed and exported to Japan. Most of these workers were casual labourers recruited by a headwoman. This casual work was extremely competitive, so those who wanted to keep their jobs had to be expert and efficient or have a very good working relationship with the headwoman.[22] One of my elderly female interviewees, Mrs. Syu, recalled how extremely competitive the job was: 'When I was in my early teens, very often I had to take a stool and then sit and wait in the queue before dawn.' However, the women were hired only occasionally and the wages they earned were very low.[23]

-

Besides working in the fish processing industries, cleaning vessel hulls was another job option for on-shore people in fishing communities. After a long fishing trip at sea, moss and barnacles grew on vessel hulls. To maintain a fine exterior, vessel owners would have the hulls regularly cleaned when the boats returned to Kaohsiung. This was not a job which required much physical strength and usually it was delegated to members of the fishers' family, like their young sons or even daughters. This unique scene from the Kaohsiung fishing port gradually disappeared in the 1970s when vessel owners began to entrust this important work to hull-cleaning professionals.[24]

-

Women in the fishing communities were in charge of the money matters for their families, although their social status was comparatively lower to that of men. In Gushan District, a large number of vessel owners' wives, daughters and even daughters-in-law worked as accountants in their fishing companies. There were two advantages in this practice: firstly, it was believed in this Taiwanese culture that women were very good at managing money matters, and secondly, vessel owners did not need to spend extra money hiring an accountant from outside. A well-known murder happened in the early 1960s, when the mistress of Lin M.Y., who served as the Head of Kaohsiung Fishermen's Association, was killed by a fisher after a violent quarrel in the company office simply because she took charge of the financial affairs of Lin's fishing company and the fisherman thought she was cheating him.[25] This practice of women taking charge of the financial affairs of fishing companies still widely exists nowadays. When I conducted my fieldwork in Kaohsiung in 2002, most accountants who worked in the fishing companies were vessel owners' wives, daughters or daughters-in-law.

-

In ordinary fishing families, wives had to take charge of the family's money matters, when their husbands were fishing in remote fishing grounds. During this time they received financial support from vessel owners on behalf of their husbands. The financial support that vessel owners or fishing companies offered took the form of a monthly payment and a loan if necessary.

-

For those men working on a distant water longliner, a fishing trip might be longer than one year. To assist fishers to support their families, every month longline companies had to provide a family allowance to the fishers' families, which was called the monthly family payment.[26] Usually this family stipend was not a great amount; just enough for the fishers' wives and children to have a simple life. Fishers' wives had to collect and manage this money.

-

Similar financial arrangements can be found in the trawl fishing industry. Trawl fishers returned to Kaohsiung every two or three months. Hence, trawl fishing companies did not provide a fisher's family with an allowance. However, to help fishers provide for their families, trawler owners were required to advance money to fishers before they embarked upon their trip. This money that the fishers borrowed all went to their wives to use while they were away. The fishers themselves did not really need to use money at sea.[27]

-

If a marine accident such as a shipwreckhappened at sea, or a foreign authority detained the crew, the fishers' family members—particularly mothers and wives—would do everything they possibly could to demand compensation from the vessel owners or the fishing companies, because that was the best way to avoid financial difficulties after the death of their husbands or sons. Usually these bereaved women would have the greatest disregard for formality and propriety and they would go to the company offices or vessel owners' residences and cry, shout and make an embarrassing public row until they received a satisfactory financial settlement. From the view of the vessel owner, fishers' family members always lodged very unreasonable claims when such accidents happened, which created further problems for vessel owners. Some disputes resulted in court action if they could not be resolved through negotiation.[28]

Women's Social Status, Marriage and Family Problems

-

Women played an important role in the onshore economic activities and household management when their husbands went fishing at sea. However, this does not mean that equality between the sexes existed in the fishing communities. In the old days, there was much superstitious sexism against females in the various fishing communities in Taiwan. For example, women were prohibited from touching fishing gear and vessels while they were menstruating. It was believed that menstructing women would attract misfortune and cause their husbands to have a poor fishing result or a dangerous fishing trip. Many of my female informants complained to me during interviews that in the early post-war years, discrimination against females was still deeply rooted in Taiwan's fishing communities.

-

As major breadwinners, husbands exercised patriarchal authority over their wives. Wives, to some degree, were just like their husbands' possessions, although they had to live independently when their husbands fished at sea. This attitude was very evident during my fieldwork in Kaohsiung. When I interviewed old fishers' wives in Kaohsiung, besides obtaining the women's approval to conduct the interview, I, more importantly, needed to have their husbands' consent. Although they knew me very well, most old fishers felt offended at my request to interview their wives, and consented to my request reluctantly. Even so the husbands were always present while I interviewed their wives. As a young man, I was not supposed to ask old women's names and ages especially before their husbands. In a conservative and patriarchally-driven community like Kaohsiung, any inquiry about an old women's personal information was culturally unacceptable.

-

In most cases, the marriages of young people in the fishing communities were arranged by their parents, who, with the help of matchmakers, looked for a prospective person of the right age for their son or daughter, then they arranged a meeting between the two parties when the fisher came home from a fishing voyage. Young fishers rarely had much choice but to marry a woman chosen for him from the same social background, because few other young women outside the fishing communities were willing to marry a fisher because of their poverty and low social status. Thus the fishers' brides mostly came from the Kaohsiung fishing communities or their hometowns, Penghu or Siao Liouciou. Normally, the two parties would get married very soon if their arranged meeting had been a success. Some couples held their weddings in their hometown; some in Kaohsiung. It depended on the personal circumstances and financial means of the two parties.[29]

-

However, a poor but talented fisher could sometimes marry a wealthy young woman. If the young man was considered trustworthy, industrious and promising, he might be able to marry a fishing master's daughter. Occasionally, some fishers even married vessel owner's daughters which lead them to experience a meteoric rise in the industry. As Syu Yicin explained, 'It was a natural thing that fishing masters introduced their daughters to you, if you were a competent and promising man.'[30]

-

But this social practice raises an interesting question. Did young women in fishing communities necessarily wish to marry a fisher? Not really, from the standpoint of social mobility. Their fathers were fishers, and their brothers were fishers as well. To these prospective brides, marrying a fisher was only just an acceptable option. In their hometowns, Penghu or Siao Liouciou, most of them had no choice but to marry a local fisher. After moving to Kaohsiung, however, when young women looked for a husband they had more possible suitors from which to choose and more opportunities to meet young men from outside the fishing environment. Often, they would not marry a fisher if they found a more suitably employed man.[31]

-

'If you marry a fisherman, you only have a half husband,' stated Cai Bian's aunt.[32] Husbands in long distance fishing families were frequently away at sea for at least half of their married lives. Thus, wives had to look after the household and raise the children largely on their own. They had to be self-reliant, strong and independent of their husbands. Hence, in a Taiwanese fishing family, basically, the real person in charge was the wife, rather than the husband; although he was the main breadwinner. If the women encountered any personal or financial difficulties while their husbands were at sea, very often they asked for help from their parents or their siblings, rather than their in-laws. Furthermore, women in the Kaohsiung fishing communities were inclined to stick together and support and help each other, because all of their husbands were away at sea. Compared to married women in other onshore communities, those in fishing communities were not as close to their husbands' families,[33] even though the patriarchal pattern of Chinese family and kinship was strongly reflected in traditional Taiwanese culture. A similar case can be found in Hull, in the United Kingdom. When fishers were working at sea, their wives always sought comfort and help from their mothers, rather than from their husbands' families.[34]

-

For a widows to remain chaste after the death of her husband was considered a respectable deed in traditional Taiwanese society. However, it was not easy to remain a 'chaste woman' in many fishing communities. Because husbands were the major breadwinners in the fishing communities, widows could become destitute if they remained chaste after the passing away of their husbands. For economic reasons, most of them chose to remarry.[35] Generally speaking, the fishers' wives could be categorised into two different types: some were industrious and thrifty in managing their households and these women raised their children with an exemplary sense of duty. Others, however, simply could not endure the hardships and loneliness, and forsook their families and either eloped with lovers or had extra-marital affairs. It is clear that the majority of fishers' wives socially conformed to their monogamous situation; however, the number of women who found the loneliness and demands of having a husband away at sea much of the time intolerable cannot be underestimated. In some extreme cases, desperate housewives sold their homes and property, left the children with their grandparents and fled with new partners. Their unsuspecting husbands, who were working at sea, had no idea what had happened at home until they belatedly arrived at Kaohsiung, landing at the dockside with several months catch.

-

None of the fishing communities of Kaohsiung were immune from such social problems and family tragedies. It is difficult to say which fishing community was more likely to suffer this kind of personal misfortune. When discussing this sensitive issue, fishers, however, always stressed that women from other fishing communities were more apt to have extra-marital affairs than those in their own community. A Penghu engineman stated: 'Yes, I admit that some wives in our community had affairs with other men. But the chance was much lower compared with other groups.'[36]

-

However, from an impartial point of view, this statement does not make complete sense. Traditionally, extra-marital affairs rarely happened before families migrated to Kaohsiung. Both the Penghu Islands and Siao Liouciou were tiny places and people knew one another very well in their everyday village lives. It was next to impossible to have an illicit love affair in such a closed and conservative society.[37] However, this was not necessarily the case after they migrated to Kaohsiung, the second largest city in Taiwan with so many strangers present and new work opportunities.

-

In addition to having affairs, other temptations, such as gambling, also made women fall into disrepute in the eyes of their husbands.[38] In their leisure time, some Penghuan women liked to play games of chance such as 'four colour cards' or mahjong with small wagers. Most of their playing partners were close neighbours or fellow villagers. To them, playing cards or mahjong was a form of local recreational activity, rather than an addictive habit, because it seldom led to serious financial disputes or family problems. However, it was no longer the case after the fishers migrated in large numbers to Kaohsiung. Gambling in this new urban environment became a serious social issue and problem for particular Penghuan families. Firstly, numerous Penghuan migrants worked in the distant water fisheries. Husbands could not readily go home as often as they had done when they had lived in Penghu. Some Penghuan wives began to fill the void in their lives by gambling. The monthly family payment fishing companies provided became their main source of money for gambling. The greater the individual stipend that they received from the fishing companies, the more risks they could take in gambling for higher stakes. In these cases, playing cards or mahjong was now more than simply a recreational activity; it became a serious, albeit risky habit that caused major family problems. Not surprisingly, this kind of household tragedy happened more often to fishers who worked on distant water longliners than to those working on pair-trawlers. The trawlers could return home every two or three months so the fishers had a better sense about the actual state of the well-being of their families.[39] One retired Penghuan fishing master said that among people in their communities, as many as five out of ten were addicted to gambling. In the most extreme cases, apartments and houses had to be sold to repay gambling debts. Some wives even worked as dance hostesses at bars to earn money to gamble or pay off outstanding debts. Most of their husbands were not aware of what had happened to their wives and families under such addictive circumstances until it was too late, when they returned to Kaohsiung from their extended fishing voyage.[40] Here, I have to emphasise that we cannot impute family tragedies to wives alone. Quite a number of fishers, after a long, tiring and abstinent voyage at sea, would also spend money lavishly in foreign ports for rest and recreation.[41] Some visited prostitutes and satisfied their sexual desires; some indulged themselves in heavy drinking bouts; and some gambled for days until they ran out of cash.[42]

Postscript

-

The number of 'women in the fishing communities' was shrinking in the 1970s for two important reasons: Firstly, the fishing communities in Kaohsiung were gradually dying out. Numerous job opportunities which were created by onshore economic activities in the metropolitan areas, particularly Taipei and Kaohsiung, encouraged young people to leave the fishing industry.[43] In 1973, 38 per cent of the distant water fishers quit their jobs; while in 1974, 52 per cent left the industry; in 1975, 65 per cent left their jobs at sea. The employment situation continuously deteriorated year by year.[44]

-

Secondly, young women in Taiwan's fishing communities were becoming more and more independent. They started to say no to 'arranged marriages' and tried to marry men who worked onshore. For these young women, marrying fishers was no longer considered a desirable choice. Hong Fucai, an old Siao Liouciou fisher, stated:

In the past, if you wanted to get married, you had to go to sea, working as a fisher to prove you could support a family. However, nowadays no one will marry you, if you are a fisher.[45]

-

I use Jiangjyun Primary School as an example. This primary school was located in Wang'an, one of the main fishing villages of Penghu. Nearly half of the school children were born to brides originally from Southeast Asia and China. This reinforces the fact that young women do not want to marry young men in the fishing villages, so half of the men are forced to 'purchase' a wife from a poor developing country. In fact, nowadays, a similar situation happens in nearly every fishing village in Taiwan.[46] The continuity of the future well-being of the fishing communities required the participation of both sexes in the marriage and the workplace. But these days no one in Kaohsiung, not even the fishers' daughters, want to marry fishers. Young fishers have thus been forced to either give up their fishing careers, or to take (purchase) a wife from China or developing countries in Southeast Asia. These foreign brides have no interest in any fisheries-related activities, and their sons are therefore unlikely to inherit their father's fishing career. Also, their daughters, just like other young Taiwanese girls, do not wish to marry a fisher like their mothers did. By the 1980s, Kaohsiung's fishing communities have stepped down from the stage of social history.[47] The images of the women, and the work they did in the fishing villages, have also gradually faded in people's memories.

Endnotes

[1] Gushan was the cradle of Taiwan's distant water fishing industry. Cijin was a less developed area. Its major fishing activities were aquaculture, coastal and offshore fisheries. The Fishing Ports of Kaohsiung City, Taipei, Fisheries Agency, 2003, p. 9. The Cianjhen fishing port was completed in 1967, which encouraged numerous distant water fishing companies to shift their offices and fleets from Gushan to Cianjhen by the late 1960s. However, Cianjhen fishing port looks like an industrial area; it would be incorrect to regard Cianjhen as a bona fide fishing community.

[2] Interview, Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002. In fact, in most fishing communities, 'the division of labour between the sexes seems in one respect quite sharp.' See Paul Thompson, Tony Wailey & Trevor Lummis, Living the Fishing, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983, p. 173. Shore work is left to, or shared with women, but fishing at sea is monopolised by men.

[3] Chen Hsien-Ming, 'The development of tuna longline fishery on Liouchiou Island,' in Geographical Research, no. 33, (Nov. 2000): 199–220, p. 201.

[4] In fact, fishermen's migration has happened in many countries. What happened in nineteenth century Britain is a good example. The Devon trawlermen shifted north-eastward to Humberside in several phases. They are called 'Multi-stage Migrants'. The Thames Fishermen moved directly to Grimsby, and then settled down there. They are called 'Single-stage Migrants'. See Margaret Gerrish, 'Following the fish: nineteenth century migration and diffusion of trawling,' in David J. Starkey, Chris Reid & Neil Ashcroft, eds., England Sea Fisheries - The Commercial Sea Fisheries of England and Wales since 1300, London, Chatham Publishing, 2000, pp. 112–17.

[5] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Interview, Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002.

[8] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002, and Guo Shihfu, Kaohsiung, 27/6/2002. It is universal that fishers' wives got involved in fisheries-related activities. I use the fishing communities on the Scottish east coast as an example. Fishers' wives in the 1970s still prepared the bait and mended the fishing gear for their husbands. See M. Estellie Smith, Those Who Live from the Sea - A Study in Maritime Anthropology, West Publishing Co, 1977, pp. 30–31.

[9] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002.

[10] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002.

[11] Interview, Guo Shihfu, Kaohsiung, 27/6/2002. See also Thompson, Wailey & Lummis, Living the Fishing, pp. 167–68. The fact that women play an important role in fish processing and in preparing for the fishery can also be found in other fishing powers. In the UK, net-mending was a home task for fishers' wives and daughters.

[12] Interview, Guo Shihfu, Kaohsiung, 27/6/2002, and Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002. The protection treatment of fishing nets and longlines was a troublesome job. Therefore, some people in the fishing communities started to shorten the process by leaving out the pigs' blood procedure, because they felt that treating the nets with red potato starch was good enough.

[13] Interview, Guo Shihfu, Kaohsiung, 27/6/2002.

[14] Interview, Guo Shihfu, Kaohsiung, 27/6/2002.

[15] Interview, Cai Minghuei's wife, Kaohsiung, 5/7/2002. In autumn and winter, oyster farmers started to have poles fixed on the bottom of the water, and they harvested oysters several months later. See The Fishing Industry of Taiwan Nantou, Department of Information, 1953, p. 11.

[16] Ibid.

[17] At that time a decalitre of rice just cost a $NT12. See The Fishing Industry of Taiwan, p. 11.

[18] Interview, Cai Bian's wife, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002.

[19] Interview, Cai Minghuei's wife, Kaohsiung, 5/7/2002.

[20] Interview, Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002.

[21] Interview, Chen Shengli, Kaohsiung, 21/5/2002.

[22] Interview, Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002; Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002 and Syu Yisin's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 evening.

[23] Interview, Syu Yisin's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 evening. See Thompson, Wailey & Lummis, Living the Fishing, p. 168. In the UK, women also made a significant contribution to the fish processing industry. They worked as gutters and white-fish filleters in fish processing factories; some worked as kipperers in smokehouses. Like fishers' wives or daughters in the Taiwanese fishing communities, they were seasonally hired, and the wages they earned were very low.

[24] Interview, Syu Yisin's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 evening.

[25] Interview, Chen Youyi, Kaohsiung, 26/6/2002 and Jheng Sanbian, Kaohsiung, 13/3/2002.

[26] Interview, Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 afternoon.

[27] Interview, Jhong Ciourong, Kaohsiung, 15/4/2002.

[28] Interview, Gu Tingfang, Kaohsiung, 23/6/2002.

[29] Interview, Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002. In fact, in Asia, marrying a person from the same social background does not only happen in societies such as conservative Taiwanese fishing communities. It also happens in the western world. The Italian fishing community in Fremantle, Western Australia is a good example. The Italians migrated to Australia, but still preferred to marry a person in Fremantle's Italian community, or get a bride from Italy. See Charles Gamba, A Report on the Italian Fishermen of Fremantle, Perth, The University of Australia, 1952, pp. 56–57. The same case is also found in Hull, UK. Most of the young fishers met prospective partners 'through the inter-connected webs of relatives, neighbours and friends.' See Tunstall, The Fishermen, pp. 141–42.

[30] Interview, Syu Yisin, Kaohsiung, 4/7/2002.

[31] Interview, Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002.

[32] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002 early morning.

[33] Interview, Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002 early morning; and Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 afternoon.

[34] Married women in the fishing communities were not very close to their husbands' families. See Tunstall, The Fishermen, p. 161.

[35] Interview, Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung,

[36] Interview, Syu Y.S., Kaohsiung, 16/4/2002.

[37] Interview, Syu Yisin, Kaohsiung, 4/7/2002.

[38] Interview, Cai Minghuei's wife, Kaohsiung, 5/7/2002; Chen Shuteng's wife, Kaohsiung, 14/6/2002; Cai Bian's female relative, Kaohsiung, 3/7/2002 early morning. and Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 afternoon.

[39] Interview, Jhong Ciourong, Kaohsiung, 15/4/2002. Regarding the family payment, there was a similar system in Britain as well. When fishers were fishing at sea they arranged for a regular weekly payment to be sent to their families. Therefore, fishers' wives were slightly wealthier than their neighbours. See Jeremy Tunstall, The Fishermen, pp. 160–61.

[40] Interview, Chen Youyi's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 and Syu Yisin's wife, Kaohsiung, 6/7/2002 evening.

[41] Interview, Chen Youyi, Kaohsiung, 26/6/2002, and Sia Fujhong, Kaohsiung, 24/4/2004. I asked my informant Sia, 'Why do many fishing masters face difficulties in their old age?' He replied 'Yes, as a fishing master, I earned a lot of money; however, I spent more.'

[42] Interview, Chen Youyi, Kaohsiung, 26/6/2002, and Liu Syuan, Kaohsiung, 4/7/2002.

[43] 'Labour shortage and the problems of running costs in the distant water fishing industry,' in Fisheries Tribune, no. 103, 1973, 3. In 1973, a novice fisher who worked on a distant water fishing vessel earned an average of $NT3,000 to $NT7,000 ($US79 to $US184) per month, which was not much better than the salary that a young man earned by working in an onshore factory

[44] Wang Anyang & Liou Sijiang, The Problems of Taiwan's Distant Water Fisheries and Research on Fisheries Policies, Taipei, Executive Yuan, 1979, p. 32.

[45] Interview, Hong Fucai, Kaohsiung, 21/5/2002.

[46] News.yam.com, 29 December 1995, online: http://yam.udn.com/yamnews/daily/2912495.shtml, accessed on 11/09/2005.

[47] I have to emphasise that Taiwan is still one of the major distant water fishing nations in the world. The total annual catch of tuna species ranked second among fishing powers in 2005, and that of squid ranked third. Most fishers are now recruited from developing nations in Southeast Asia and from China.

|