Performing Gender in Maoist Ballet:

Mutual Subversions of Genre and Ideology in

The Red Detachment of Women

Rosemary Roberts

[D]ance may play a role in forming the consciousness and reflexivity of a people. The kinetic images of who performs what, when, where, why, how, with or to whom, come from and create a climate in which gender roles are defined. Sometimes expressive forms, such as dance, perpetuate the pervading ideology of gender; at other times they impugn and undermine it.

-

In 1967 at the beginning of China's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, Jiang Qing, wife of China's Chairman Mao Zedong, declared eight works of performance art to be the new models for proletarian literature and art. These works were dominated by class ideology, and each was designed to give prominence to one perfect central proletarian hero among proletarian heroes, set up as models of the new socialist man and woman to be emulated by the entire nation. These works, comprised of five modern Beijing Operas, an orchestral symphony and two ballets, were the first group of famous 'model works' or yangbanxi that were to dominate Chinese culture for the next nine years.[2]

-

As part of a broader study of the representation of gender in Maoist culture, this article will make a case study of one of the yangbanxi ballets to examine the tensions that arise when a strident, gender-egalitarian revolutionary ideology is expressed through an art form that has grown from a very different set of ideological and gender assumptions. Western classical ballet is an art form that relies on the body to express meaning, emotion, and even individual brilliance, and is based firmly in a bourgeois, romantic tradition. This would seem to place it inherently at odds with the puritanical revolutionary ideology of the Cultural Revolution that tabooed the exploration of love, romance or sexuality, and emphasised subordinating a relatively androgenised self to the collective. Focusing on the full-length ballet The Red Detachment of Women,[3] this study examines the performance of gender in this revolutionary ballet in the light of this incongruity of genre and ideology and considers the following issues: To what extent were the traditional modes of gender representation of classical ballet challenged by Maoist ideology, particularly the Maoist drive to promote female equality? Conversely, how were Maoist ideology and the drive to promote female equality subverted by the artistic conventions of classical ballet? Mainland Chinese scholarship in the post Mao period, strongly supported by a group of Chinese diasporic writers, has characterised Maoist culture and the yangbanxi as genderless and sexless.[4] Does analysis of dance in the yangbanxi ballet support this position?

-

In exploring these questions, I will make use of contemporary theories on dance, gender, bodies, spectacle and sexualities by writers including Ramsay Burt and Judith Hanna, while also considering Chinese traditional representations of the body and Chinese understandings of dance and gender.[5]

The foundations of Chinese ballet

-

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in October 1949, the new socialist government of the 1950s promoted the development of China's indigenous traditions and also sought to demonstrate New China's cultural sophistication by developing elite Western art forms. Both Chinese traditional cultural forms and Western elite culture were to be used to serve the class interests of society's new masters, the peasants, workers and soldiers.[6] It was in this cultural and political environment that the first national ballet school was established in Beijing in the mid–1950s as part of the Beijing Academy of Dance. At the time the Soviet Union was not just China's closest cold war ally but also world-renowned for its brilliant ballet tradition. China's fledgling ballet school was therefore established with the assistance of Soviet expertise.

-

Russia had become the world leader in classical ballet excellence and innovation through the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg before the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, and in the Soviet period it maintained an outstanding reputation through the Leningrad Kirov (the former Imperial Ballet) and the Bolshoi in Moscow. Soviet ballet was renowned for the technical brilliance of its dancers and for the prominence it gave to its male dancers not as mere props for the ballerina as had become the practice in European and British ballet, but as virtuoso performers in their own right. Soviet choreographers produced new ballets with heroic revolutionary themes such as The Red Poppy (1927), but also continued to stage the earlier classics such as Swan Lake, and create definitive versions of romantic works such as Romeo and Juliet. Political constraints on artistic freedoms, however, kept Soviet ballet stylistically conservative, despite radical innovation and experimentation in ballet in the West.[7] It was this rigorous and conservative Soviet school that fostered China's first domestically trained ballet dancers in the second half of the 1950s and directly or indirectly trained the dancers and choreographers of China's first indigenous ballets, Hongse niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women) and Bai mao nü (The White-haired Girl). Liu Qingtang, star of The Red Detachment of Women, for example, was trained by specialist teachers from the Soviet Union at the Beijing Dance School beginning in 1956. He in turn became a specialist teacher of the pas de deux, and played a part in choreographing the first ballet version of The Red Detachment of Women.[8]

The model ballets

-

The development of indigenous Chinese ballet was a continuation of efforts initiated in 1963 by the then Premier of China, Zhou Enlai, to make literature and art 'more revolutionary, popularized and nationalized.'[9] The early performances of China's first ballet schools had been traditional Western classics including Swan Lake, Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty. After watching a Beijing Ballet School performance of Esmeralda, however, Zhou Enlai had suggested that the ballet school move beyond foreign ballets about 'princes and fairies' and try to create something more revolutionary such as a work depicting the Paris Commune or the October Revolution.[10] In response, the Beijing Ballet School went a step further and directly proposed a ballet with a revolutionary Chinese theme based on the popular 1961 film Hongse niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women). The film told the story of a slave girl who escaped from a tyrant landlord, joined the women's detachment of the local communist forces and returned as a mature revolutionary to defeat her former oppressor. With the approval of Premier Zhou and under the guidance of the Deputy Minister of Culture at the time, Lin Mohan, the new ballet was publicly performed in mid–1964. In early 1964, the Shanghai Dance Academy took inspiration from the example set in Beijing and developed the ballet Bai mao nü (The White-haired Girl) based on the popular play, opera and film that dated back to the 1940s.[11] To create a uniquely Chinese ballet form, both works incorporated elements from traditional Chinese opera including martial arts moves, acrobatics and the frozen pose or liang xiang used in opera to convey the spirit and emotion of the character. Chinese folkdances were also inserted for added colour and variety. Both of these ballets were continuously performed and revised (in accordance with the designated method of literary creation at the time), until they were included in the first group of eight Cultural Revolution 'model works' (yangbanxi) in 1967.[12] They underwent further modification for definitive film versions produced in 1971 (Hongse niangzi jun The Red Detachment of Women) and 1972 (Bai mao nü The White-haired Girl) respectively.[13] These officially produced film versions, were familiar to almost all mainland Chinese of that era, and are the works which this study uses for its analysis of the performance of gender in the yangbanxi ballet.

The ideological foundations of the yangbanxi

-

As noted above, the yangbanxi were works designated as models for a new proletarian literature and art by Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, who took charge of cultural matters during China's Cultural Revolution (1966–76).[14] The theory and ideology underpinning these model works were drawn directly from party cultural policy of the Yanan period in the early 1940s when communist power was limited to small remote base areas (Mao's was based around the city of Yanan in Shanxi province) and needed to draw the surrounding peasant populations to their cause. The concept of the model work was outlined in a policy statement published in the Renmin Ribao on 29 May 1967.[15] Based on readings of five of Mao's key writings,[16] the document stressed the importance of ideologically correct literature and art to the success of class struggle and the proletarian revolution. Cultural works were to stress both artistic and ideological excellence.[17] They were to draw critically upon indigenous traditional culture, refining, developing and enriching existing forms.[18] They were also to remould foreign classical art forms to serve the revolutionary purpose. The basic task of the new culture was to create heroic models of workers, peasants and soldiers,[19] showing their struggles and sacrifices while displaying optimism in their ultimate victory against class enemies.[20] Heroes could not be 'middle' characters (that is, display weakness or doubt), could not display moral or disciplinary laxity, and were not to die in a contrived tragic end. [21] Class enemies could not be portrayed with any sympathy or glamourised. The document also criticised works that were 'concerned only with love and romance.' Such works were declared 'bourgeois and revisionist trash' that was to be 'resolutely opposed.'[22]

-

The requirements for literature and art of the time were also mapped negatively through criticism of works deemed ideologically unsound. In the area of film, many works were condemned for depicting traditional scholar and beauty type romances, for depicting revolutionaries distracted by love, and for 'pornographic' depiction of bodies and beauties. Feudal ideology was also condemned.[23]

-

At the same time, since the 1950s, the party's efforts to realise equality for women and mobilise them into the workforce led to the promotion of a series of national models of women who were physically and mentally capable and tough and who undertook occupations and exhibited behaviour traditionally associated only with men.[24] The female ideal was no longer a frail, helpless ornament confined to the domestic sphere, but a sturdy, active, unadorned woman contributing to the revolution as the equal of men. Women were spurred on by Mao's famous 1965 remark that 'times have changed, men and women are now the same,'[25] a comment that came to symbolise the gender egalitarian ideals of the Cultural Revolution era. Another favourite catch cry of the time was: 'Anything that men can do, women can do too.' This slogan revealed that male/female equality was to be based on masculine values and qualities as the norm. The ideological basis of the content of the yangbanxi therefore could be summarised as promoting the ideal of heroic men and women uniting as equals under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party to fight against class and national enemies in order to realise the victory of the proletarian revolution.

Gender in dance performance: a methodology for analysis

-

Contemporary dance theory offers new understandings of the ways in which gender is socially and culturally constructed though dance. In Dance, Sex and Gender, Judith Hanna argues that the kinetic visual models displayed in dance performance reflect, maintain or challenge society's expectations for each sex's specific activities and patterns of dominance. Which dancer (male or female) performs what, how, why and whether alone, or with, or to another dancer can shape viewers attitudes to and opinions on gender characteristics and gender-power relations. To assist in the analysis of specific dance performances, Hanna offers a method of analysing patterns of gender representation in dance through a system of digital coding of variables.[26] While this present study will not go as far as digital coding, Hanna's list of variables creates a useful catalogue of different elements of dance that can perpetuate or challenge pervading ideologies of gender. These variables include modes of interaction between dancers, various aspects of individual action, and whether elements such as music and costume are gender differentiated. Since I have considered the issue of costume in the yangbanxi elsewhere, and since the relationship between music and gender in the works is a substantial topic in itself and hence beyond the scope of this present study, here I will focus on various aspects of individual action and interaction between dancers.[27]

-

Hanna's list is grouped under categories of space, effort and time: 'Space' lists the ways dancers might pose, move and gesture individually and touch or be touched by other individuals. 'Effort' refers to the amount of strength and energy that the dancer conveys to the audience (this is not the same as the amount of effort actually used, as the classical ballerina, for example, must often use great strength and effort to convey to the audience the appearance of fragile, effortless grace). 'Time' is used to define whether a character initiates movement or waits for others to initiate movement. Each category includes a range of movements marked as 'A'-assertive, or 'P'-passive as follows:[28]

Space: posture, locomotion, gesture, touch

(A= assertive, P= passive)

|

|

|

|

Individual action

|

|

Wide postural stance predominates (A)

|

|

Narrow postural stance predominates (P)

|

|

Relatively larger movement (in verticality, horizontality, distance covered excluding effect of body size) (A)

|

|

Throws own body (gymnastic moves such as tumbling and handstand, falling to knees, rolling) (A)

|

|

Limb moved as unit (A)

|

|

Successive, differentiated or articulated movement within limbs (e.g. break at wrist) (P)

|

|

Makes fist, flexes bicep (A)

|

|

Cries (P)

|

|

Smiles (caring)

|

|

|

|

Interaction

|

|

Pushes, propels, lifts, dips, fights other dancer (A)

|

|

Pushed, propelled, lifted, lowered, defends self (P)

|

|

Grasps, squeezes, or manipulates other's body parts (A)

|

|

Grasped, squeezed or manipulated (P)

|

|

Supports a dancer (A)

|

|

Clings to or leans against other dancer (P)

|

|

Touches, pats, strokes, brushes other (caring)

|

|

Stares/glares (A)

|

|

Stared/glared at (P)

|

|

Initiates directional changes in group interaction (A)[29]

|

|

Reacts to such changes (P)

|

|

|

|

Effort

|

|

Strong, tense (A)

|

|

Gentle, relaxed (P)

|

|

|

|

Time

|

|

Does not wait, begins actions (A)

|

|

Waits for action, responds to action (P)

|

Table 1. Elements for Analysing Gender Coding in Dance

-

A-type actions are culturally understood in the West to denote authority, power, dominance and aggression, while P-type actions denote dependency, subordination and empathy. In classical ballet, A-type actions are usually performed by male characters while P-type actions are usually performed by females. Evidence for similar cultural conventions in the Chinese tradition can be found in gender and power differentiated roles in traditional Chinese opera. Training manuals for Beijing Opera, for example, clearly differentiate between the movements of male and female characters: when miming travelling on foot (paoyuanchang) for example, the male performer must take firm broad steps and walk with his left fist raised. In contrast the female performer must walk with tiny steps at a slower pace and place her left hand on her hip in a more closed stance. He must look horizontally ahead, while she must cock her head down and to the left.[30] Chinese scholar Huang Yufu, in a study of the qiao—the special shoes worn by Beijing Opera performers to simulate women with bound feet— sees the kinetic conventions of traditional Beijing Opera as directly reflecting the powerlessness and subordinate status of women in Chinese society, and perpetuating common attitudes such as 'men are strong/powerful, women are weak' (nan qiang nü ruo), and 'men are superior, women are inferior' (nan zun nü bei).[31] Hanna's list therefore has relevance in the Chinese cultural context. I will apply it to the yangbanxi ballet The Red Detachment of Women below to consider to what extent kinetics in the ballet challenged or supported the gender conventions of both classical ballet and the Chinese cultural tradition.

Yangbanxi kinetic analysis

-

This research requires a highly detailed analysis of dance and movement, so it is necessary to limit data to a small section of the ballet. The analysis below will therefore, focus on Scene Two from The Red Detachment of Women,[32] though I will also refer to other scenes from the yangbanxi ballets where relevant.

-

As mentioned above, The Red Detachment of Women, tells the story of a slave girl Wu Qinghua. Qinghua escapes from the prison of the 'Tyrant of the South,' and is assisted by Hong Changqing, the Communist Party representative attached to the new women's company of the local communist forces. He directs her to join the army where she trains to become a revolutionary fighter. In the film version of the story, Qinghua and Changqing fall in love, though this subplot is eliminated from the 1971 film version of the ballet. Changqing is captured by the Tyrant and immolated as the communist armies approach. Qinghua, now a mature revolutionary, kills the Tyrant and takes over Changqing's role as party representative.

-

Scene Two of The Red Detachment of Women depicts the women soldiers' base and training camp. The women soldiers drill under the direction of their female company commander and the male Party Representative Hong Changqing. The escaped slave girl, Wu Qinghua, arrives at the camp, pours out her grievances to sympathetic villagers and soldiers and is welcomed into the Red Army. The dance segments that comprise the scene have been summarized in the table below:

|

Ref

|

Description of action

|

No. and sex of dancers M/F

|

Characteristics of movement

|

Comments

|

|

1

|

Villagers and Red Army in joyful dance of welcome for army women

|

|

All dancers do identical steps

|

|

|

2

|

Army women march in with 2 officers

|

Group – F

Commander?F

Party rep ?M

|

Women march in with wide firm strides identical to the male officer

|

|

|

3

|

Female commander reviews and then prepares to drill troops

|

Solo – F

|

Graceful leaps in one line followed by pose on point with fists above the head. Then tight pirouettes, followed by an expansive commanding pose directed at the women soldiers

|

Her action is initiated by a signal from the party representative Hong (male)

|

|

4

|

Army drill with guns

|

Group – F

|

Small steps, pirouettes, then strides and arabesque with gun in hand. Movement along single straight line in single steps with movements close to the body.

|

|

|

5

|

Army drill with sword

|

Solo – M

|

Very expansive and energetic movements around and across stage

|

The energy and authority of the action contrast with the previous women's dance

|

|

6

|

Army drill with swords

|

Group – F

|

Movements are in tight circles in one spot

|

|

|

7

|

Hand grenade practice

|

Solo – F

|

Energetic leaps travelling back and forth along a line. Also small fast steps and tight pirouettes. But not expansive arms

|

In the background the other women bang their swords on the ground vigorously

|

|

8

|

Gun drills

|

Group – F

|

Expansive lunges in the gun drills, but done on one spot

|

At the end the male officer signals the female officer and she dismisses the women

|

|

9

|

Dagger dance

|

Group of 5 militia men

|

Very expansive movements, not just with arms and legs, but also travelling across the floor. When approaching the camera they look straight into it in a challenging way unlike the women who mostly avoid looking straight at it

|

The men run on and go to the male officer not the female for their order to drill. Afterwards the male officer directs the female officer to go and congratulate the male dancers

|

|

10

|

Celebrations

|

M and F group

|

Identical steps and forward leaps

|

|

|

11

|

Humorous skit

|

Group: 4 girls and one boy

|

Boy does jump/lifts assisted and supported by the girls and then does virtuoso turns solo while the girls move from side to side on one spot

|

Four girls enter with boy who clowns in a dunce cap, pretending to be a class enemy

|

|

12

|

Celebrations

|

Group – F soldiers and militia men

|

Starts with all doing identical mirrored steps in pairs, but then moves into gender differentiated steps with the men in stereotypical masculine poses—expansive, very wide-legged, hands on hips—while the women do tiny steps from side to side with hand raised half hiding the face in the classical female style. Note the males are in the front line with the women behind. The men have chins raised assertively while the women's faces are half hidden, heads cocked on one side with chin down in classic non-assertive pose. Then the men do vigorous leaps to alternate sides while the women simply raise and lower their hands

|

|

13

|

Qinghua arrives at the Red Army camp

|

|

|

When Qinghua arrives Hong grasps her shoulder and arm and guides her. The Female officer gives her an arm hug and later an embrace

|

|

14

|

Pouring out grievances

|

Solo – F (Qinghua)

|

Expansive, forceful movements, but limited travel across floor

|

|

|

15

|

Deciding to join the army

|

Qinghua – F

F officer

M officer

|

F commander and M party rep jointly support Qinghua, then F supports her alone.

|

|

|

16

|

|

Solo – M

|

Leaps and fast travelling across stage

|

|

|

17

|

Qinghua expresses determination

|

Solo – F

|

Raises and turns on one spot (fouettes) then series of turns around a circle

|

|

Table 2. The Red Detachment of Women Scene Two Dance Summary

-

In the two sections that follow I will analyse the gender significance of the dance segments described in Table 2 using Hanna's two major categories of the spatial aspects of dance movement - 'individual action' and 'interaction' (See Table 1). I will also briefly consider the influence of role assignment on the choreography used in The Red Detachment of Women.

-

As the synopsis and table above indicate, the narrative development of The Red Detachment of Women, offers many opportunities for roles and movements that challenge the gender conventions of classical ballet. Women commanding troops and performing military drills with weapons could be expected to, and indeed do have a greater range of roles and physical movements than a swan princess or Sugar-plum Fairy.[33] When reviewing her troops, the female company commander strides along with firm authoritative steps, her strides matching exactly those of the male officer beside her, symbolically attributing her with power and status paralleling his. Her solo dance and that of the female soldier practicing grenade throwing are characterised by energetic high leaps, lunges, expansive gestures, and arabesques with fists instead of soft fingers. The company commander issues commands with an authoritative gesture and pose. Arm and leg movements of the women soldiers are overall much wider and much more energetic and forceful than the small, dainty self-enclosing movements of female dancers in either classical ballet or in traditional Chinese theatre. In many places, instead of the gentle, effortless manner projected by the traditional ballerina, the women convey strength and tension in their poses. In conveying the yangbanxi themes of class struggle and class spirit, the female dancers' gestures and facial expressions also frequently display anger and determination, emotional expressions that also challenge both ballet conventions for representing positive women, and the range of publicly expressed emotions acceptable for women. In semiotic terms, the yangbanxi female dancers' use of greater individual bodily space and more overtly energetic movements are a mark of increased assertiveness and power.

Figure 1. Qinghua and the company commander drill with rifle and hand grenade. Still from Scene Four of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women), Beijing Dianying Zhipianchang, 1971.

Figure 1. Qinghua and the company commander drill with rifle and hand grenade. Still from Scene Four of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women), Beijing Dianying Zhipianchang, 1971.

|

-

In Figure 1, which shows Qinghua and the company commander performing military drills, the choreography embodies many of the elements discussed above: the women move quickly across the stage, executing high energetic leaps. Their bodies are fully extended in powerful open postures. In contrast to the conventional curved limbs of female dancers in classical ballet, the arm holding the hand-grenade is taut and straight, conveying a sense of power and purpose. The introduction of individual female dance movements that were similar to those of male dancers symbolised the increased social status for women and the gender egalitarian ideals of the time, which, as I explained earlier, were based on the idea that 'men and women' are the same.

-

Nonetheless, it is notable that even for the soldier roles, gender differences that continue to embody gender hierarchy are also in evidence. Compared to the dance movements of the women, the stance and arm movements of the men overall continue to convey a much greater sense of width, speed and energy and hence dominance of the stage. This cannot be attributed simply to the greater physiological strength of men because it is not merely that they jump higher or turn faster. Echoing Burt's observations of classical ballet, in the scene being analysed, the choreography of the women's dances tends to limit women to movement either in small circles around a single point or along a single axis, or in a straight line.[34] In contrast, the choreography of the men's dances has them moving quickly and expansively to all parts of the stage.

-

Male dominance is further reinforced by camera angle and the use of gaze. As the women soldiers dance their army drill, the camera observes them from a distance. Only rarely does one of the women glance momentarily at the camera. Even when the line of women soldiers runs one by one past the camera they do not look into the lens. They are brave and determined, but nonetheless a spectacle to be observed unchallenged by the audience (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figures 2 and 3. The women zig-zag across the stage towards the camera which is focused on the point of their final turn. As they approach the camera they keep their gaze down and towards stage right. As they change direction the head flicks across without looking at the camera, and the eyes now look up and away from the camera towards the left of the stage. The body is thus presented to the viewer's gaze without any challenge from the gaze of the performer. Stills from Scene Two of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun.

-

In contrast, the group dance of the male Red Guards (the village militia) includes a series of steps in which the group of five dancers begins at the rear of the stage, and then moves to the front of the stage and back again. As the men approach the front of the stage they all engage the camera at close quarters with a bold and challenging stare. The audience observes them, but they gaze back refusing to be objectified and proclaiming their dominance in a way not allowed the women (Figures 4 and 5).

Figures 4 and 5. The continuous direct, bold eye contact of the men as they approach and then retreat from the camera at the front of the stage forms a strong contrast with the averted gaze of the women soldiers in Figures 2 and 3. Stills from Scene Two of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun.

-

When the two groups, women soldiers and male militia join together for a mass dance at the end of the scene, classical gender stereotypes also reassert themselves. After an initial sequence of identical steps with men and women side by side (see Figure 6 below), the women move behind the men. While the men perform wide, deep lunges, the women on pointe perform tiny rapid steps from side to side, arms alternating in fourth position to frame and sometimes partly conceal the head and face in a movement that could have come straight from Swan Lake (see Figure 7 below). The men then perform energetic jumps while the women simply raise and lower their arms. Male dominance and the gender hierarchy are hence subtly maintained by stage positioning, and by the contrast between the wide open stance and assertive energy of the males and the narrow postural stance, low-energy movement and semi-concealment of the females. In this respect we could conclude that the gender egalitarian ideals of the Cultural Revolution have been undermined by the gender stereotyping embedded in classical ballet choreography.

Figures 6 and 7. The gender conventions of classical ballet reflected in the choreography of the yangbanxi model ballet. Although group choreography at first symbolises gender equality (left), it then reverts to the gender conventions and implicit gender hierarchy embodied in classical ballet. Stills from Scene Two of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun.

-

If we move on to consider interaction between dancers, similar complexities are in evidence. In classical ballet it is usually male dancers who push, propel, lift, fight, grasp, manipulate body parts and provide support for other dancers. Women dancers are usually the recipients of such actions. This strict gendering of roles sets up an implicit gender hierarchy of male/handler dominating the female/handled. In the yangbanxi ballets, however, both male and female dancers support, lift, push, propel and fight other dancers. In the scene I have examined, the female company commander, first with the male party representative and then alone, supports the slave girl Wu Qinghua as she poses on pointe. Four girls lift a youth doing assisted jumps. Later in the ballet Qinghua is portrayed in physical battle with the evil landlord and his men, pushing, kicking and fighting with gun and sword. Clearly, women's roles have been expanded across previous gender boundaries in a challenge to the gender norms of the ballet tradition and in a symbolic empowerment of women.

-

A close analysis of these interactions however, shows that the fundamental gender hierarchy of power embedded within them remains, but has been blurred by complications of class. Both male and female characters are choreographed with the whole range of assertive and passive interactions, but whereas the female characters are all positive, the male characters are divided into positive (proletarian revolutionaries) and negative (counter-revolutionaries), and significantly only the latter are choreographed with the passive role in interactions. Hence in The Red Detachment of Women, women are supported by other women and lifted, supported and assisted by both positive and negative male characters. In addition, male enemy soldiers are lifted and supported in acrobatic moves by positive male characters during simulated fights (in fact the most complex lifts in the ballet are male-male lifts.) No positive male character, however, is lifted, supported or assisted in any way by other males or females at any time in the 1971 official film version of the ballet. Read in the light of Hanna and Burt's argument that the dancer who lifts and manipulates others is culturally kinetically coded as more assertive and dominant than the dancer who is lifted or manipulated, dancer interaction within the ballet sets up an implicit hierarchy in which the positive male characters clearly occupy the highest level of power and dominance. The single exception to this observation in fact seems to verify its validity: the positive youth who in The Red Detachment of Women, Scene Two, is assisted in a vertical leap by four girls is at the time clowning in a dunce cap and pretending to be the evil landlord. He is not therefore a positive male handled by women, but a notional evil male being handled by women. Below the positive males at the top of the gender hierarchy, the relative status of the positive females and the negative males as expressed in kinetic discourse is rather ambiguous. Two points derive from this: first that underlying the seemingly gender egalitarian images of the yangbanxi lurks the traditional gender hierarchy, and second: the kinetic systems of the yangbanxi implicitly link the female with the counterrevolutionary while conversely, the negative characters are feminised by being choreographed with steps and movements otherwise performed only by women and never by revolutionary men. To sum up we can say that despite the Cultural Revolution denunciation of 'feudal ideology', the semiotic systems of the yangbanxi themselves continued both the traditional gender hierarchy and the traditional conflation of both female and evil within one concept—yin. Without a discursive separation of the two concepts, the yangbanxi could not promote complete equality of the sexes.

On bodies and sensuality

-

Cultural Revolution moral discourse and cultural policy eschewed the overt depiction of sensuality, sexuality and romantic love. Love and sex were seen as unworthy distractions for the dedicated revolutionary, and any suggestion of bodies or sexuality was denounced as pornographic. This makes the choice of ballet as a vehicle for conveying Cultural Revolution ideology quite problematic. Ballet is about bodies on display. The fact that it uses bare flesh and bodies in form-fitting costumes to convey all meaning and create aesthetic enjoyment makes it inherently sensual, and when these bodies are men and women dancing together and touching, connotations of heterosexuality are easily evoked. This is particularly the case in China where as John Hay has argued there was no cultural tradition of regarding the body as an object for aesthetic appreciation as existed in the west.[35] In the Chinese tradition, male and female bodies displayed together meant sex not art. In a further contradiction of ideology and art form, classical ballet relies heavily on display of the passive female body as an object of desire, something incompatible with the Cultural Revolution drive for female equality and empowerment.

-

The creators of the film versions of the yangbanxi ballets seem to have had some awareness of these difficulties and appear to have tried to adapt classical ballet to create a style of ballet that met Cultural Revolution ideological requirements.[36] This can be seen most clearly in their treatment of the heterosexual pas de deux.

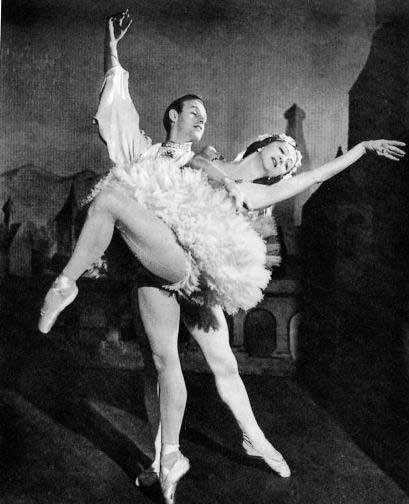

Figure 8. The passively gazing classical ballerina subject to the dual gaze of audience and her male partner. Raymond Burt, The Male Dancer: Bodies, Spectacle, Sexualities, London and New York: Routledge, 1995 p. 54.

Figure 8. The passively gazing classical ballerina subject to the dual gaze of audience and her male partner. Raymond Burt, The Male Dancer: Bodies, Spectacle, Sexualities, London and New York: Routledge, 1995 p. 54.

|

-

The pas de deux in classical ballet typically centres around the male grasping the woman's waist, thigh or groin and manipulating her body in lifts, dips and turns often in a metaphor for romantic love and sexual desire. In The Red Detachment of Women, however, pas de deux between the hero and heroine (who are lovers in the 1960 film) have first of all been almost completely eliminated, solving the problem of implicit sensuality by avoidance. Second, where pas de deux are choreographed, bodily contact is minimised to his grasping her shoulder or her grasping his fingers to stabilise her arabesque. This removes from the ballet some of its most aesthetically-pleasing and popular elements and highlights a triumph of the puritanical and prudish morality of the cultural ideology of the time.

-

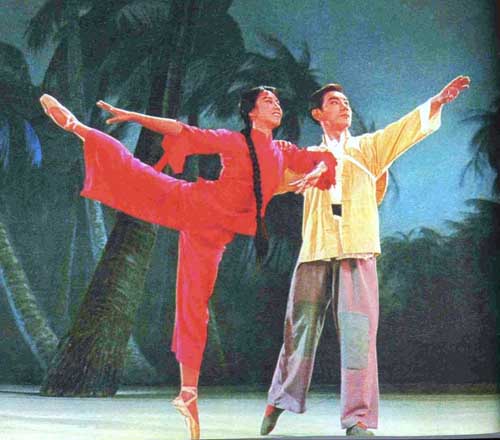

In a related point, the pas de deux has also been modified to eliminate classical ballet's dual objectification of the female body. From Figure 8 it can be seen that in the classic pas de deux pose, the female gazes passively and invitingly at the audience while the male gazes at her adoringly, hence also diverting the gaze of the audience on to her.[37] In contrast, in the yangbanxi, gaze is consistently controlled to deflect attention away from individuals' bodies and sexualities. Take for example the most famous pose from The Red Detachment of Women known as 'Changqing points the way' (Figure 9). In this pose, Qinghua and Changqing both gaze out at an abstract communist future. She does not engage the audience and he does not look at her. The pose simultaneously denies classical ballet's implicit sexuality and challenges its objectification of the female body.

-

In their attempt to eliminate romance and sexuality from yangbanxi performances, however, the creators of the yangbanxi ballets were unable to neutralise what Hanna has called the extra dimension in which ballet is performed—that of the imagination.[38] 'Changqing points the way' became one of the most popular pictures of the Cultural Revolution era, appearing on posters, and decorating all kinds of household objects. Lifted out of the political narrative, the image of Qinghua posed elegantly in form-revealing red silk supported by the hand of the dashing, heroic Changqing, fires the romantic imagination and undermines the asceticism of Cultural Revolution ideology.

Figure 9. Changqing points the way. Still from Scene Two of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun.

Figure 9. Changqing points the way. Still from Scene Two of Fu Jie, Pan Wenzhan (dir.), Hongse niangzi jun.

|

Concluding Remarks

-

The analysis above has shown that the relationship between genre and ideology in The Red Detachment of Women was multi-layered and highly complex. In some ways this revolutionary ballet is a radical appropriation of a classical bourgeois genre by a proletarian and gender-egalitarian ideology. Classical ballet's romantic tales of lovelorn girls pining for elite ruling-class males, are replaced with the tale of a peasant girl who revolts against ruling class tyranny, joins the Communist army and eliminates her former oppressors. Thematically, traditional gender representation is undoubtedly radically challenged, and this is supported by a major expansion of the scope of roles and movement permitted the female dancer, and a reduction of her function as an object to be viewed with desire. Nonetheless, to a certain extent the art form itself subverted the ideology it was intended to promote. In many ways, The Red Detachment of Women preserved kinetic conventions of classical ballet that support traditional gender stereotypes and perpetuated the gender hierarchy that affords power and dominance to the male.

-

The issue of gender, sexuality and the yangbanxi ballets becomes even more complex when we consider issues of diversity within the Chinese audience of the time.[39] Memoirs of the time show that different audiences saw them in very different ways: young urban women of the time have talked of the inspiration they gained from the yangbanxi's images of strong independent women;[40] ballet masters saw them as a travesty of their art;[41] peasants were startled by the morally suspect display of bodies, and at least one young man had his first interest in sex aroused by the sight of the bare thighs of the ballet-dancing women of the Red Detachment.[42]

-

So how should one assess the role of this yangbanxi ballet? In terms of gender, it promoted a major change in the way that women viewed their own roles and possibilities, but at the same time made it clear that their new roles were to remain within a broader framework of subordination to masculine hegemony. Aesthetically, although restrictive in many ways, the yangbanxi ballets could also be seen as extending Chinese tradition to incorporate a new understanding of the body as object for aesthetic appreciation. In both respects, the performances both created and broke barriers for what was permissible both on stage and in society. Artistically, the yangbanxi ballets were a very bold experiment by a very young school of ballet. Although they are technically quite limited compared to the whole range of the classical ballet repertoire, (probably reflecting the realities of the level of training and experience of dancers in China at the time), they were very innovative in their incorporation into ballet of elements taken from traditional Chinese performance arts including folk dance, martial arts and acrobatics.

-

After the Cultural Revolution, like the rest of the yangbanxi the ballets were exiled to the political wilderness, but in recent years both The Red Detachment of Women and The White-haired Girl have been regularly restaged and are now recognised as the foundational works of an indigenous Chinese ballet. The Red Detachment of Women was even chosen for the inaugural performance at the new National Opera Theatre in central Beijing in October 2007.[43] In the light of discussion in this article, however, it is significant to note that the new works include signs of a significant retreat from the gender radicalism of their predecessors: the chorus of village women from The White-haired Girl, for example, who in the yangbanxi version practiced a vigorous militia drill with long handled pikes, now dance waving long colourful ribbons—the substitution of a symbol of masculine power with a symbol of feminine objectification. It is a fascinating reflection on the relationship between dance, gender and society that this small change in choreography and props in one scene of a ballet can function as a metaphor for the re-feminisation, re-objectification and disempowerment of women that took place in mainland China in the post-Mao period.

Endnotes

[1] Judith Lynne Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender: Signs of Identity, Dominance, Defiance and Desire, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 242.

[2] The first group of model works, designated in 1967, included: the modern revolutionary Beijing Operas Hong deng ji (The Red Lantern); Shajiabang; Zhiqu weihu shan (Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy); Haigang(On the Docks); and Qixi Baihutuan (Raid on White Tiger Regiment); the Symphony Shajiabang; and the ballet versions of Bai mao nü (White-haired Girl) and Hongse Niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women). Some of the better-known works from the second group of model works designated in 1972 include the operas Du juan shan (Azalea Mountain); Long jiang song (Song of Dragon River); Pingyuan zuo zhan (Fighting on the Plains) and Panshiwan (Boulder Bay) and the opera version of The Red Detachment of Women. There were also two more ballets: Yimeng song (Ode to Yimeng) and Caoyuan ernü (Sons and Daughters of the Grassland).

[3] Hongse niangzi jun (The Red Detachment of Women), performed by the China Ballet Troupe, filmed by Beijing Dianying Zhipianchang, 1970.

[4] See for example, Yue Meng, 'Female images and national myth,' in Gender Politics in Modern China, ed. Tani E. Barlow, Durham: Durham University Press, 1993, pp. 118–36; Mayfair Mei-hui Yang, 'From gender erasure to gender difference: state feminism, consumer sexuality, and women's public sphere in China,' in A Space of Their Own: Women's Public Sphere in Transnational China, ed. Mayfair Mei-hui Yang, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999, pp. 35–67. Another aspect of the work of this group of scholars is the argument that in Chinese communist literature and art, the bodies of women were appropriated by the Communist party to promote their discourse of liberation and modernity (see, for example, Meng's article above). While I certainly acknowledge some validity in this argument I believe that it pays too little attention both to the transformation of young male bodies, and to the many female characters in the yangbanxi operas and ballets who do not fit this particular model. Further, it does not acknowledge the non-communist origins of some of the 'liberation' tropes it represents as being imposed on female images by the communists. Because of my reservations concerning this field of scholarship, I do not incorporate their ideas into the current study.

[5] Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender. Raymond Burt, The Male Dancer: Bodies, Spectacle, Sexualities, London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

[6] One of the famous slogans of Maoist culture was 'use the past to serve the present, use the foreign to serve China.'

[7] For example choreographers in the West challenged the gender conventions of classical ballet by showing women performing traditionally male movements, reversing sexes in lifts, or showing male-male lifts, see Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender, chapters 9 and 10.

[8] Dai Jiafang, Yangbanxi De Fengfeng Yuyu (The Turbulent History of the Yangbanxi), Beijing: Zhishi chubanshe, 1995, p. 252.

[9] This was known as the 'san hua' (three '-isations') campaign. This in turn was a continuation of 1950s cultural policy that encouraged the development and enrichment of Chinese culture by drawing on indigenous folk traditions as well as learning from and adapting foreign music and dance.

[10] According to Dai Jiafang, in Yangbanxi, p. 94, Zhou thought it would be necessary for Chinese ballet to go through an intermediate stage of producing works with more revolutionary but still foreign themes before being able to move onto revolutionary Chinese themes.

[11] Dai, Yangbanxi, p. 102. The White-haired Girl is a peasant girl who fled to the mountains to escape the cruel landlord who killed her father and raped her. In the mountains her hair turns white from lack of nourishment. She is finally rescued by her former fiancé who has joined the communist forces and returned to liberate his village. She joins the army and marches off at his side.

[12] For an overview of the creation and selection of the first set of yangbanxi, see Rosemary Roberts, 'Positive women characters in the model revolutionary works of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: an argument against the theory of the erasure of gender and sexuality,' in Asian Studies Review, vol. 28, no. 4 (2004), pp. 407–22.

[13] See Note 11 and Bai Mao Nü performed by the Shanghai Ballet Troupe, film directed by Xie Tieli.

[14] See note 2 and Dai Jiafang, Yangbanxi, pp. 189–90.

[15] It was published under the title 'Summary of the Forum on the Work in Literature and Art in the Armed Forces with which Comrade Lin Biao entrusted Comrade Jiang Qing' and was reported as largely comprising the text of a speech presented by Jiang Qing in February 1966. An English translation can be found in Five Chinese Communist Plays, ed. Martin Ebon, New York: The John Day Company, 1975. For a detailed study of party policy and performance practice in the Yenan period see David Holm, Art and Ideology in Revolutionary China, Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1991.

[16] The five works were 'On new democracy,' 'Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art,' 'Letter to the Yanan Peking Opera Theatre after seeing Driven to Join the Liangshan Mountain Rebels, 'On the correct handling of contradictions among the people' and 'Speech at the Chinese Communist Party's National Conference on Propaganda Work.'

[17] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 8.

[18] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 11.

[19] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 13.

[20] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 18.

[21] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 19. For a detailed examination of the characteristics of the hero in Cultural Revolution fiction see Yang Lan, Chinese Fiction of the Cultural Revolution, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998, pp. 40–96. For related reading in the area of the politics of gender in communist China see Shenti de wenhua zhengzhixue (The Cultural Politics of the Body), ed. Wang Anmin, Kaifeng: Henan daxue chubanshe, 2004; Shenti zhengzhi (Body Politics), ed. Ge Hongbing and Song Geng, Shanghai: Sanlian, 2005.

[22] 'Summary of the Forum,' p. 19.

[23] About 20 percent of a list of 400 films designated as poisonous weeds were criticised for their depiction of love or issues of sex and sexuality. See Ducao ji you yanzhong cuowu yingpian sibai bu, online: http://www.boxun.com/hero/wenge/104_1.shtml, accessed February 20, 2008. Item 96 on this list, for example the film Shuishang chunqiu, is criticised for its display of beautiful women and thighs.

[24] The earliest models post 1949 were women who had served courageously in the communist forces during the civil war. As the 50s progressed the military women were gradually replaced by peasant or worker heroines, such as rural women who saved crops from floods before saving their homes and women drilling teams on oil-fields.

[25] Mao made this remark on seeing some young women swimming in the Ming Tombs Reservoir near Beijing, but it later became a catch cry of the Cultural Revolution, and taken to an extreme was used to justify demanding that women perform the same physical labour as men such as carrying equally heavy loads on their backs.

[26] This is offered in an appendix to her main work. See Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender, pp. 253–55.

[27] I have examined costume in the yangbanxi in 'Gendering the revolutionary body: theatrical costume in Cultural Revolution China, in Asian Studies Review, vol. 30, no. 2, (2006):141–59.

[28] I have deleted from Hanna's list items that are not relevant to this study, such as those related to costume and music, and added four items drawn from analysis earlier in the book as indicated in Note 29.

[29] This and the following item, as well as the two items listed under Time, are taken from Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender, p. 160.

[30] See Wang Feng, Jingju (Beijing Opera), Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 2006, pp. 144–48.

[31] Huang Yufu, Jingju, qiao he zhongguo de xingbie guanxi 1902–1937 (Beijing opera, qiao and gender relations in China 1902–1937), Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007, pp. 135–36.

[32] I selected this ballet because the theme of women soldiers offers more scope for kinetic action that challenges dance and gender conventions than the plot of The White-haired Girl, which more closely mirrors the stereotyped tradition of female victim rescued by heroic male lover.

[33] Classical ballet is typified by tragic narratives of unrequited or thwarted love that centre on the ardent yearnings, ecstasy and emotional suffering of a lovely, young female (often a mystical or exotic creature yearning for an aristocratic male). Whereas in early ballet men and women performed the same steps, the modern classical form became highly gender differentiated. The principal male danseur functions chiefly to enhance the ballerina's role as the embodiment of ultra-feminine elegance, grace, beauty, passion and emotion. He does this by supporting her as she poses or spins on pointe, by executing lifts, or by handling her in other aerial moves. He also contrasts her ethereal style of dance with his own vigorous displays of athletic masculinity. The corps de ballet (dance chorus) enhances visual spectacle. They reinforce the aesthetic or emotional intensity of a solo, or provide interludes of light-hearted relief between episodes of intensifying tragedy. Variety and colour is often brought to performances through elements of national and folk dance inserted into the plot as festivals and weddings. Ideally, music, costume, sets and dancing all function together to create a cohesive product and elevate aesthetic and emotional experience. Carol Lee, Ballet in Western Culture: Its Origins and Evolution, New York: Routledge, 2002.

[34] Burt, The Male Dancer, pp. 54–56.

[35] John Hay, 'The body invisible in Chinese art?' in Body, Subject and Power in China, ed. Angela Zeto and Tani Barlow, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

[36] At this stage this is just conjecture based on the evidence of the works themselves. Further work needs to be done on the intentions of the choreographers and producers of the time.

37 See Burt, The Male Dancer, pp. 54–57.

[38] Hanna, Dance, Sex and Gender, p. 242.

[39] This is an issue that would benefit from further investigation, but is beyond the scope of the current study. Nonetheless, although I cannot discuss audience response in detail here, I raise it briefly to indicate that I do not believe that there was one single, unified Chinese audience response to the yangbanxi. Although the content of the yangbanxi was completely inflexible and controlled, the way individual readers or viewers responded to the yangbanxi varied considerably and was, to a large extent, beyond Communist Party control.

[40] See for example Xiaomei Chen, 'Growing up with posters in the Maoist Era,' in Picturing Power in the People's Republic of China: Posters of the Cultural Revolution, ed. Stephanie Donald and Harriet Evans, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc, 1999, pp. 101–37

.

[41] See Li Cunxin, Mao's Last Dancer, Ringwood, Vic.: Viking, 2003.

[42] See speakers in the Documentary film, Yangbanxi, The 8 Modelworks, directed by Yan Tingyuen and produced by Hetty Naiijkens and Retel Helmrich, 2006.

[43] Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for providing this information.

|