Competing for Women:

The Marriage Market as Reflected in Folk Performance

in the Lower Yangzi Delta[1]

Anne E. McLaren

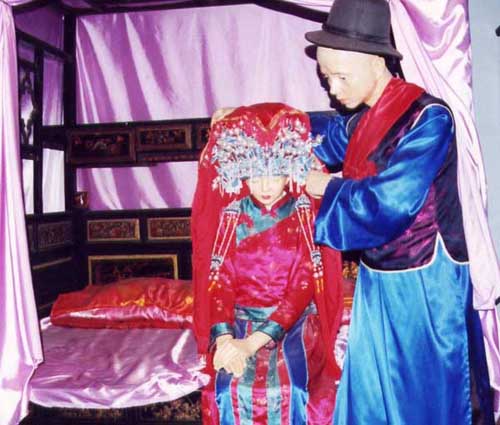

Figure 1. The bridal chamber. Recreation in the Folk Museum, Gulangyu, Fujian. Photo taken by the author, November 2000.

|

-

Males have generally dominated the demographics of China, both historically and in the present day. Sex ratios were relatively equal during the 'socialist' period (1950s–1978) but in the decades since the beginning of the reform period in 1978, the gender balance has returned to the skewed ratios of the past. In the 2000 census in China, the sex ratio for children under the age of five was found to be 118.38 males to 100 females compared with a figure of 109 males to 100 females in the 1982 census.[2] In contemporary China, the only regions with an at-birth sex ratio of less than 110 males to 100 females are the relatively undeveloped borderlands of Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Guizhou, Tibet, Ningxia, Qinghai and Xinjiang.[3]

-

For those who have observed the 'One child policy'[4] in China over the past two decades, all this was entirely foreseeable. A devaluation of females as opposed to males is the underlying reason for this skewed sex ratio, but what makes it all possible is the ready availability of ultrasound in newly affluent areas and the ease of legal access to terminations of pregnancy. The social acceptability of using ultrasound to control the sex of the child is a strong contributing factor. Already China is seeing the rise of a new class of young bachelors, an upward pressure on demand for marriageable women, and, in some areas, a return of the abduction and sale of women.

-

What is it like to be born female in a country where women are generally in short supply? I first began to think of the imbalance of the sexes and the social consequences when researching the oral culture, folk performance and marriage practices of the lower Yangzi Delta region. Since the mid 1990s I have been investigating the historical wedding customs of non-elite farming populations in the Shanghai hinterland, including 'aberrant' marriage customs such as 'marriage by abduction' and bridal laments.[5] These local customs were widely prevalent in the lower Yangzi Delta before the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 but have been little studied by either Chinese or Western scholars for a range of complex reasons.[6] My own work has been based on analysis of historical materials, transcripts of songs and performance traditions. I have also gained insights from interviews with women who came of age before 1949 and also with amateur ethnologists of the region.[7]

-

Needless to say, the folk genres amongst the mostly illiterate farming communities of the lower Yangzi never deal with population control or imbalanced sex ratios. However, their wedding songs and marriage practices, transmitted down the generations, implicitly reflected a world where there are never enough marriageable women. In trying to understand the sex imbalance of the present day, it is useful, I think, to reflect that this imbalance is simply a return to past practices. One could say that ultrasound followed by sex-selective abortion has replaced female infanticide and the relative neglect of female infants as a way of ensuring the greater survival of males. From a long-term historical perspective, it is the relatively balanced sex ratio of the socialist period (c. 1950–1980) that is unusual. How did women historically respond to the implacable demographics of their communities? How did the (usual) shortage of women shape the oral and ritual traditions which they both transmitted and created? To what extent could they use these traditions to exercise agency in a patriarchal society? These are the questions I will address in this paper.

Figure 2. The Bridal Party. Recreation of a traditional marriage departure scene in the Xiamen Folk Museum, Gulangyu, Fujian. Photo taken by the author, November 2000.

|

-

Laments present a good case study for those interested in notions of female agency in the Chinese performance context. There are two main types of lament in China: the bridal lament known as 'weeping on being married off' (kujia 哭嫁), which is only performed by women, and the funeral lament, known as 'weeping at the funeral' (kusang 哭喪) where women predominate but which can be performed by men. Laments are thus a rare example in Chinese folk traditions of a female–dominant genre. Bridal laments were performed in many regions of China well into the mid-twentieth century, and are still performed today amongst the Tujia people of the upper Yangzi River region, and non-Han Chinese minority groups in the borderlands. In imperial times, marriages were generally exogamous and patrilocal, which meant that brides left their natal home and village to live permanently in the home of the groom and subject to the authority of his parents. This is still the preferred marriage pattern in China, although intra-village marriages are now a lot more common than in the past. Before 1949, a man generally had one wife (qi 妻), but if affluent could have a number of concubines (known as qie 妾). Laments were performed only in the case of marriage to a primary wife, a form known as 'major marriage.' (Concubines, on the other hand, were sold into the man's home and entered his family with little ceremony). Marriages were arranged by both parents through the medium of a matchmaker and the couple did not meet before the wedding. The point of departure from her natal home was thus a crucial time of transition for the bride, who was typically in her adolescent years. The elaborate art of kujia, performed in the days before her departure, became an important rite of passage and a signifier of her intelligence and ritual competence. For this reason, the bride-to-be spent many months mastering the lament repertoire from women in her district in preparation for her wedding.[8]

-

Laments were transmitted amongst illiterate Chinese women in rural areas and no transcriptions were apparently made before the 1960s. Our knowledge of laments today thus comes not from living performances but from transcriptions made decades ago, often by local enthusiasts. This presents a challenge to the researcher who must rely not on fieldwork in situ but on transcripts of transmitted laments and interviews with former practitioners.[9] The establishment of socialist China in 1949, the advent of new marriage laws, and the decline of the arranged marriage, meant that the tradition of 'weeping on being married off' became seen as an embarrassing remnant of 'the old society.' The new socialist bride had a say in her choice of partner and no longer wept and wailed in protest at her marriage.

-

In many regions of pre-socialist China, bridal laments were performed for a period of at least three days before the bride's departure. In some regional traditions only the bride and her mother performed the lament; in others the bride was assisted by a chorus comprising her sisters, female relatives and unmarried girls from the village. Typically, the bride would seclude herself in a separate room. This could be her bedroom in the case of laments performed in Nanhui, in the Shanghai hinterland. Her dowry would be laid out around her: bolts of cotton cloth, bedding, coverlets, barrels, furniture and other household goods. The mother would usually begin the lament by calling on the bride to behave with propriety in her new home and submit to the authority of her parents-in-law. The daughter would interrupt her from time to time with her protests, sobs and expressions of anxiety at her enforced removal from her natal home. After this initial exchange, the bride would then express her thanks to each of her family members in turn, including her male relatives. She would additionally perform specific laments at various times during the farewell ceremony, for example, when she was offered a final bowl of rice, when she was carried into the bridal sedan, when she farewelled the family on her departure and so on. The bride would cease lamenting only when the home of the groom appeared in view. To continue to wail would only bring bad luck to her new home.[10]

-

Chinese bridal laments are an excellent example of verbal art, to use the term of Richard Bauman in his well known study, 'Verbal Art as Performance.'[11] They are replete with poetic devices such as metaphors, similes and analogies. But they are also a 'communicative phenomenon,'[12] where the performer seeks to elicit a certain response from the audience and is in turn evaluated by the audience on her 'success' in inducing expected emotions in her listeners. As one would expect, the performer is seeking to induce feelings of sorrow in her audience, in fact, if they do not weep tears, then her performance has lost its ritual potency.[13] Lament traditions are known world-wide and overwhelmingly associated with women.[14] In common with other scholarship on laments, I focus here on the way laments expressed women's grievances, and the extent to which laments afforded a degree of agency to women practitioners. However, I would argue that the Nanhui lament (and possibly the Chinese lament in general) is not so much the expression of an individual grievance as an oral tradition produced collectively by a 'folk community' and bound by the generic 'rules' of its own regional tradition. This sets limits to individual 'agency' but lends the performance the authority of a ritualised tradition valued by its community.

-

In order to assess what women do in their laments it is important to understand the parameters of the genre, which I set out briefly here. Laments are distinct from the usual sung entertainment forms known to Chinese culture. For example, a ballad, lyric or dramatic aria is referred to as a ge 歌 or 'song' in Chinese. However, Nanhui practitioners do not regard kujia or kusang as a ge but rather as a ku or form of stylised wailing with sobbing.[15] The Nanhui lament is chanted in simple melodic lines of uneven length and irregular rhyme. Performers and their audience commonly weep tears during the lament and lines often end in a low slurred note akin to a sob. The low-pitched wailing out of the chanted lines invites the listener to join in and share the lamenter's sorrow, and is thus crucial to the affective powers of the Chinese lament.[16] Unlike Chinese ballads, arias and lyric songs, none of the known regional traditions rely on musical accompaniment, although the sound of the lament and the poetic imagery and themes relate broadly to the folk ditties and music of the region.[17] Laments are always performed in the local language and the formulaic repertoire abounds in images drawn from the region. In the Nanhui repertoire with which I am most familiar, these images revolve around the woman's labour in the home and in the cottage cotton industry. In a traditional context, all women within a lament community would be expected to perform a lament that would have the desired emotional and ritual affect and a woman's overall talent and competency would be judged on how well she did this.

-

One could conclude from the above that the act of weeping and wailing (ku), when carried out in the appropriate ritual context, was understood as a very particular kind of performance. It was deeply embedded in everyday practices and burdened with a ritual and emotional intent unknown to entertainment performance genres. While the repertoire was formulaic and 'traditional,' it was not learnt by rote but mastered as a poetic art that could be flexibly adapted to the exact circumstances of the performer. This quality of adaptability within a familiar repertoire, together with the liminality of the time of performance (upon marriage or death) gave a degree of authority to the performer, who, subject to her mastery of the repertoire, could control the emotions of the audience. Bauman has observed that this sense of 'control' by the performer had a 'potential for the transformation of the social structure' and for this reason performers could be 'admired and feared.'[18] It follows from this that the traditional and formulaic quality of bridal laments, common to oral performance in general, does not vitiate the agency they can afford the lamenter. Formulaic traditions are thus not intrinsically 'inauthentic' or 'valueless' by dint of being based on familiar material and poetic tropes. Similarly, the potentially transformative power of a ritual performance lies not so much in the verbal content, which can be highly formulaic and traditional, but in what is achieved by its performance.

-

One important goal of the lamenting bride was to carry out her filial duty as the departing daughter to express her gratitude to her parents by expressing her sorrow on leaving.[19] Filial piety (孝) was a central aspect of Chinese cultural values in the imperial era and remains a strongly affirmed value today. But after marriage, the daughter was encouraged to turn her filial devotion to her parents-in-law; only sons were expected to carry out life-long filial duties to their natal parents. In addition, in some lament traditions including that of Nanhui, the bride also sought to enact a type of ritual power, based around the perceived exorcistic power of weeping to rid the community of the forces of misfortune surrounding the departure of the bride.[20] These two functions of laments are sometimes articulated by lament practitioners or transmitted in popular sayings and legends.

-

Beyond articulations by practitioners and their community, one can seek to explore the implicit 'message' of laments, particularly their ritualised aspect. According to Durkheim, ritual ceremony brings to the surface and restores the underlying social order, in this way legitimising the existing system.[21] As I discuss here, the Nanhui bride through her performance renders visible the fundamental market mechanism dominating the marriage transaction. In this sense the lament asserts the inevitability of marriage customs that transferred a woman from her natal home into the economic unit of the husband's family. In Durkheimian terms, it restores the underlying order of the traditional marriage. However, I argue that this 'rendering visible' of the market mechanism that is normally invisible or left unstated in the canonical Chinese marriage ceremony is in itself an act of protest and subversion. The implication here is that patriarchy is most dangerous when performed 'invisibly' and most subject to contestation when its inner workings are brought to the surface in 'public' performance.

-

In contradistinction to Durkheim, Nicholas B. Dirks has called for ritual performance to be historicised as a site for 'contestations of the social order.'[22] But how can one determine the 'meaning' of a lament performance? As with many oral performance genres, the Chinese lament is contradictory and no single 'message' can be discerned. Elsewhere I have discussed the 'discourse of female subordination' found particularly in the initial lament 'dialogue' between the mother and daughter.[23] Here I will focus rather on the discourse of protest and contestation that runs throughout the entire lament in the words of the bride (as distinct from her mother). It is these contradictory discourses that form the poetic repertoire at the disposal of the lamenting bride. One would also expect that the competing discourses also helped to shape her female subjectivity.[24] Holland, Skinner and Adhikari in their study of the 'suffering' (dukha) songs of Nepalese women performed at the Tij festival, have noted the importance of Tij songs as a poetic and imagistic resource from which the women drew in everyday life. They conclude that these songs were important in the formation of 'their sense of themselves as females' and argue that the Tij songs offered space for 'alternate subjectivities.'[25] Following on from Holland, Skinner and Adhikari, I will focus on how the young bride constructed her own life-cycle through the poetic medium of the lament and will argue that the woman's perceived self-value at different times in the life-cycle is a crucial theme in Nanhui bridal laments, one that relates to the particularities of the marriage market in this rural community.

The Marriage Market in the Lower Yangzi Delta

-

Infanticide was widely practised in the lower Yangzi Delta (and many other regions of China) during the late imperial period (c. 1550–1911). Nanhui, located on the eastern coastal flank of the Yangzi River Delta, was part of Songjiang prefecture in 1816. In that year the ratio of male to female in Songjiang was determined to be 128:100. Figures for Nanhui county followed the general trend of sexual imbalance until the time of western penetration and the Taiping Rebellion in the mid nineteenth century, which led to large loss of life and an outflow of males from the area.[26] The customary shortage of pubescent women, together with various socio-economic factors,

led to the emergence of a range of marriage forms. The only one relevant to the lament tradition was the 'major marriage,' where the women becomes the principal wife of her husband. This was the marriage form with the highest status and the only one that guaranteed a dowry to the bride in all but the poorest of families. Concubinage was prevalent amongst affluent families in the lower Yangzi Delta before 1949. Child marriage was also practised and less commonly, a form of levirate marriage (marriage to the younger sister of a deceased wife). Another practise of the poor and desperate was abduction in marriage.[27] Men at the very lowest echelon of society were unable to marry, and formed a large pool of unsettled often vagrant men on the margins of society.

Figure 3. Shuyuan village scene, Nanhui, east coast of China. The cottage in the foreground is no longer used as a residence. It is typical of those prevalent before 1949. Photo taken by the author, December 1997.

|

|

|

-

In order to marry in the major mode, a man was required to come up with the bride price requested by the bride's family. This varied according to the economic circumstances of both sides and the state of the local marriage 'market' for women. It was customary to use the bride price to pay for the bride's dowry, which allowed the bride to depart with a large number of household goods that the young couple would then use to start their own family. The 'transaction' in the major marriage form was thus not a case of 'buying and selling in marriage' (to use the disparaging term used in socialist China of marriages in China's 'feudal' past) but a mechanism to allow both families to provide for the basic living of the newly married couple and to compensate the bride's family for the loss of her labour.

-

The Nanhui bride was probably unaware of the uneven demographics of her region. But she was aware of the practice of infanticide, the differential valuing of boys and girls, and above all, the intricacies of the local marriage market that would determine her own personal destiny. As I will discuss here, her performance of kujia provides a window into how she constructed her own life cycle and, ultimately, her own value.

-

The study below is based on the bridal lament cycle of Pan Cailian, possibly the longest Chinese lament cycle available in transcription.[28] This lament appears to be typical of bridal laments in the Shanghai hinterland. Much of the formulaic material can be found in other laments, although my informants assured me that Pan was a particularly good practitioner of laments. In Pan's cycle, the bride discusses the attitudes of her parents at the moment of her birth.[29] This of course was the crucial moment for the survival of the young girl infant. Would they keep her, abandon her, or simply drown and discard her in the wooden barrel used to remove human waste?[30] This choice was played out countless times in families of the poor in coastal Nanhui. The mother of the bride tells her daughter that when she was born her father only sat and smoked by the stove and did not complain at all. This is a sign of special favour from the father (since most would carry on about how unlucky it was to have a girl). In other words, the mother is telling the daughter that when she was born the father did not seek to try alternatives two or three as outlined above. The bride shows that she has grasped this point, indeed she may already have witnessed what happened to her infant siblings as she grew up. During the lament, in her address to her father, she turns roundly on him, declaring he should have killed her at birth instead of raising her only to cast her out:

Dear father,

You should have simply killed me when I was born and that is all,

You should have struck me three times with the shovel and twice with the hoe, and put an end to me,'

But now you have raised me for over twenty years, only to send me forth as someone's wife...[31]

-

Like many exaggerated words uttered by the bride in her lament, this is hyperbole. Infants were not struck with farm implements and killed in barbaric fashion by their fathers. If no one was available to adopt the infant, then the most common practice was drowning in a pan of water. The bride here is simply using a highly exaggerated means of expression to argue that she should not be married off now that she has come of age. But she is uttering this hyperbole in a situation where she knows that she could have been disposed of at birth.[32] She is implicitly showing an awareness of infanticide as a common practice in her village. The point of her outburst is thus that she was spared this premature end. Her father, as head of the household, made the choice to raise her. From the bride's point of view, this demonstrates that her parents cherished her at the point in the life cycle when she was most vulnerable.

-

Even in the 1990s, Nanhui villagers could discuss infanticide routinely. In Nanhui I met one elderly woman who was introduced to me as someone who had been treasured from birth by her family.[33] The family story went that if she had been born male the infant would have been drowned. In this case the family had several boys and actually wanted a girl in preference to a boy. The same woman was given a lavish dowry by her family when she married and her parents even refused a bride-price from the groom's side to signal her importance to them. The refusal of a bride-price would have given additional face to the woman and bolstered affiliative ties and obligations between the two families. One could conclude that the common custom of female infanticide provided one of the frameworks against which women found their value. Those who did live to grow up could see this as a sign that they were indeed cherished by their families.

-

This takes us to an interesting paradox in the life of the young girl. She is most devalued at birth—will her parents decide to keep her? Her parents will make a careful calculation based on their economic circumstances. But as she reaches reproductive age she grows incrementally in value. In her lament the bride shows that she understands this as well. As babies, girl infants were worth virtually nothing; they were a liability. However, a healthy girl who had been trained to work like her mother was of significant value for her production of cotton textiles, as well as her reproductive and sexual services. We know from various sources that the work of women in cotton textiles in the late imperial era was of fundamental importance to the family in this region. The males of the family worked in the fields and grew rice paddy, a portion of which had to be paid in tax to the government. The cotton spun and woven by the women was sold for cash and provided in many cases virtually the only source of cash that the family possessed. It is actually possible in some cases to trace the changing monetary value of the girl within the life cycle. For example in the northern Yangzi Delta area (Subei) in the 1930s, a very young girl could be sold for ten yuan but a seventeen year old girl sold for 50–60 yuan. According to Kathy Le Mons Walker this was 'slightly more than twice the annual wage of a male agricultural labourer.'[34]

-

The Nanhui bride shows a keen interest in the marriage negotiations, as constructed in her lament. She also offers her own commentary or interpretation of these negotiations. The nub of the issue for the bride is to determine her personal value as exemplified by what her family has chosen to outlay for her dowry. This will demonstrate to the local community and to the groom's family how much she is valued by her own family. She is also very interested in the size of the bride price paid by the groom's family, which demonstrates her value in the local marriage economy.

-

The first stage of the lament is performed in the bride's bedroom, with her mother responding to her, and her girlfriends and siblings forming part of the shifting audience. The objects to be bundled up in her dowry are laid out all around the room as she sings. The bride refers time and again in her lament to the size of her trousseau and the items within it—bedding and mattresses wrapped in ceremonial red cloth, silken coverlets, indigo blue shorts, satin quilts, and so on. In the various stages of the lament the bride thanks each family member for stinting on themselves to provide lavishly for her trousseau but at the same time she hints perhaps they can give just a little more, in order to give even more face to the family as she sets off.

-

The bride price is what the groom's family, through the matchmaker, pays the bride's family. As reflected in Nanhui laments, this is usually paid in cash, that is, silver ingots. Various trays of silver are sent, referred to as 'the large tray' and 'the small tray.' The bride is very aware that her value is determined by the overall balance or difference between the dowry and the bride price so she demonstrates an intense interest in the relativities between the two. It is this relativity that will determine her status in her new home. If the dowry is very lavish, this will give the bride and her natal family a lot of face. But if the bride's family has called for a large bride price then this signals a relative loss of face for the bride as she appears to be 'sold' out rather than given away as a cherished daughter. If a large bride price is accepted then what should happen is that this money then goes to provide an extra lavish dowry. However, in the case of poor families, the bride price often goes to provide the necessities of life such as 'oil, soy sauce and coarse rice cakes.' The dowry is consequently meagre.

-

Through the lament the bride debates the relativities of the dowry-bride price in her case. At one time she imagines that her father turned down the tray of cash from the groom's family, to indicate that they valued her too highly to 'sell' her off in marriage. She also constructs a view of her family members as having gone without for a long time in order to save up for her dowry. But her mother, who is arguing the case with her in the lament, claims that on the contrary they asked for a huge bride price and accepted it gladly. Even worse, they also accepted other gifts (foot basins, barrels, copper and tin vessels). At one point, the mother even goes so far as to declare 'A girl from a wealthy family has a rich dowry/ But a girl from a poor family is just put up for sale!' The bride's preference is for a small bride price and huge dowry—the mother constantly contradicts her and says that the family is so poor they have had to demand a large bride price and can only offer her a meagre dowry.

-

As for the reality of marriage transactions in Nanhui, we know that the relative value of bride price and dowry varied from one region to another within China.[35] Arthur Wolf's survey in the early 1980s of pre-1949 practices show that in the Jiangsu and Zhejiang area (which includes Nanhui), bride prices tended to outweigh dowries in value.[36] Hill Gates believes this is due to the market value of women's labour in textiles, which was more prominent in the lower Yangzi Delta than in north China. This meant that the acquisition of a woman in her prime into the groom's family was a significant addition to the financial resources of that family and consequently a loss to the natal family. A higher bride price paid to the bride's family helped to compensate for this loss.[37] Historical sources testify that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries bride prices were indeed higher in the Nanhui and Pudong area and that the poorest men could not afford to get married.[38] The dowry and bride price were two distinct items in the marriage exchange. The dowry was basically a series of household goods given to the bride by her natal family or prepared by the bride herself before departure. The dowry was often paid for with money from the bride price but it was regarded as belonging to the bride. The dowry was important to the material status of the bride once married, and to the face of the natal family in the local community, however the size of the dowry was more discretionary than that of the bride price, which was the subject of intense negotiation.[39]

-

The Nanhui bride understands this as well—this accounts for her insistence that the bride price be spent on the most lavish dowry possible. The bride has grown up with images of herself as a commodity to be weighed. In her lament she declares she was born stupid, a fact as certain as the nail banged into the measuring scales. This refers to the fact that it was the relative position of the nail that determines the balance of the scales. She also talks of herself as 'discounted goods' (zhetou huo 折頭貨). At the same time, the bride's imagery is permeated with images of successful women workers, especially the senior women of the groom's family who are depicted as paragons of female labour in cotton textiles, with their goods sold for high prices in Shanghai. She shows an implicit awareness that one day she too will become a senior woman just like the senior sister-in-law and mother-in-law and enjoy recognition for her hard work and competence within the family. In other words, the bride-daughter shows an understanding that her value and status will rise significantly as she proceeds through the life cycle.

-

Does the bride's evident understanding of the basic economic forces that determined her life chances, including the value of her labour in cotton textiles, allow her a certain level of agency in her life circumstances? Generally scholars have put the case that the strong role of women in textile production in the lower Yangzi did not do much to alter women's status. One can cite here the work of Kathy Le Mons Walker on the Subei,[40] and Lynda S. Bell on the Lake Tai region, two other regions in the Yangzi River Delta area.[41] They note that the income generated by women was controlled by the family and that women worked inside the household under strict control. Hill Gates also notes the 'invisible' nature of women's work because it was pooled with the family's assets. She adds that in any case the work of women was seen as a 'special gendered form of "obedience" carried out by subordinate kinswomen.'[42]

-

While not disagreeing with the thrust of these arguments, I feel it is not the complete picture. It overlooks the symbolic associations of the products of women's labour. Women's folk performance is full of proud references to women's labour and its economic contribution to the family.[43] In Nanhui today, women show off their hand woven bolts of cotton with pride. The implements they used, the spinning wheels, often beautifully carved, are still cherished objects, although no longer used to spin. The bride in her laments disparages her own level of skill but is well aware that one day she will be like the senior women, able to produce beautiful and valuable cotton goods that will win praise from the family. As she gazes around her bedroom, she sees the cotton and other goods she

has personally made, now serving as a display of her talent and skill. Gates has argued that 'as objects for [marriage] exchange, women could not be actors' and are thus rendered 'culturally invisible.'[44] However, one could well argue that laments make women's labour and skill highly visible to her listening audience. It is precisely when her economic worth is most prominent in her life-cycle that the bride uses the medium of laments to publicly dramatise her 'value.' Although the bride is not an 'actor' in the marriage negotiations, nonetheless this folk genre allows her to be a highly articulate and emotionally charged 'commentator' on the marriage exchange. Further, through her role as aggrieved 'victim,' the bride seeks to draw out bonds of sympathy and obligation from her natal family, bonds she hopes will remain even after her removal from her parents' home.

Figure 4. A woman in Sanlin, Nanhui, proudly displaying some of her cotton handicrafts. Women were still making cotton bolts by traditional methods well into the 1990s in this area. Photo taken by the author, June 1999.

|

|

|

Conclusion

-

I have suggested that the Nanhui bridal lament implicitly expresses a form of female agency, one which seeks to expose and manipulate the economic mechanism that inheres in the exchange of dowry and bride price in the major marriage mode. This is a significant finding, because the canonical marriage rituals, as laid down in the Liji, Book of Rites, and elaborated in countless popularisations, sought to render invisible the 'commercial' or monetary aspect of the major marriage and preferred to dwell on the different but complementary roles of the male and female in marriage.[45] Excessive negotiations for bride price and dowry were considered vulgar and frowned upon.[46] The implication is that bridal laments (at least in this regional tradition) allowed a woman to bring to public contention the haggling carried out by the matchmaker in the lead up to her marriage. The bride's commercial construction of the meaning of marriage exposed the underside of the canonical meaning of marriage and to an extent subverted it. In this way one could conclude that while the bride 'performed patriarchy' through the simple act of submission to patrilocal marriage, at the same time she exposed and subtly 'undermined' patriarchy through her lament.

Endnotes

[1] This paper was presented, under a different title, at the University of Queensland symposium, 'Performance and Text: Gender Identities in the East and Southeast Asian Context,' July 21–23, 2006. Some of the ideas here were first rehearsed at a seminar at the China Centre, Australian National University, Oct 14, 2004. I would like to thank Helen Creese and Louise Edwards, who organised these events, and also anonymous reviewers for pertinent comments that I have not always had time to pursue in this article, but that will inform my ongoing thinking about the issues discussed here. Some sections of this paper are included in more detailed form in my forthcoming book, Performing Grief: Bridal Laments in Rural China, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

[2] Valerie M. Hudson and Andrea M. den Boer (eds), Bare Branches: The Security Implications of Asia's Surplus Male Population, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004, pp. 131–32.

[3] Susan Greenhalgh and Edwin A. Winckler (eds), Governing China's Population: From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005, Table 7, p. 267.

[4] In Chinese this policy is known as 'planned reproduction' (jihua shengyu). The regulations do in fact permit more than one child in some cases, and the Western label is somewhat misleading.

[5] See Anne E. McLaren, 'Women's work and ritual space in China,' in Chinese Women: Working and Living, ed. Anne E. McLaren, London: Curzon Routledge, 2004, pp.169–87; Anne E. McLaren, 'Mothers, daughters, and the socialisation of the Chinese bride,' in Asian Studies Review, vol. 27, no. 1 (2003):1–21; Anne E. McLaren, 'Marriage by abduction in twentieth century China,' in Modern Asian Studies, vol. 35, no. 4 (October 2001):953–84; Anne E. McLaren and Chen Qinjian, 'The oral and ritual culture of Chinese women: the bridal lamentations of Nanhui,' in Asian Folklore Studies vol. 59 (2000), pp. 205–38; Anne E. McLaren, 'The grievance rhetoric of Chinese women: from lamentation to revolution,' Intersections: Gender, History & Culture in the Asian Context, Issue 4, September 2000, online:

http:/intersections.anu.edu.au/issue4/mclaren.html, site accessed 30 January 2008.

[6] One reason is political sensitivity. These customs are generally associated in the Chinese mind with peoples outside the mainstream Han ethnic population. Another reason is that the mostly male scholars of folk customs and performance arts in China find it easier to deal with traditions for which there are transcripts available in manuscript or print, as is often the case with performance arts practised by men. A third reason is a general ignorance about the performance and ritual arts practised by illiterate women who only know their native dialect. These women are rarely included in Chinese language scholarly research into folk performance traditions. An exception is the work of Hong Kong musicologist, Ruth Yee, who has studied the laments of Tujia women. Westerner anthropologists were not permitted to conduct fieldwork in China before 1979. For this reason, most Western studies on women's oral traditions and laments have focused on Hong Kong and Taiwan. For the relevant literature see my forthcoming book, Performing Grief.

[7] I am particularly indebted to my long-term collaborator, Professor Chen Qinjian of East China Normal University, Shanghai. See our joint study, 'The oral and ritual culture of Chinese women.'

[8] This summary of lament characteristics is drawn from my forthcoming book, Performing Grief.

[9] My study of laments in the Shanghai hinterland is based on transcripts made from recordings of elicited performances in the 1980s, and supported by numerous visits to the region with local ethnologists. For full details see Acknowledgements in Performing Grief.

[10] I relied on transcripts of Nanhui bridal laments found in Ren Jiahe, Hunsang yishi ge, Shanghai: Zhongguo minjian wenyi chubanshe, 1989.

[11] Richard Bauman, 'Verbal art as performance,' in American Anthropologist, New Series, vol. 77, no. 2 (June 1975):290–311.

[12] Bauman, 'Verbal art,' p. 291. On the gendered nature of Chinese folk culture, see Steven P. Sangren, 'Separations, autonomy and recognition in the production of gender differences: reflections from considerations of myths and laments,' in Living with Separation in China: Anthropological Accounts, ed. Charles Stafford, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, pp. 53–84.

[13] Inducing strong emotions in performer and audience is critical to the ritual effect. As Victor Turner notes, in ritual 'the dominant symbol brings the ethical and jural norms of society into close contact with close emotional stimuli.' Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967, p. 30.

[14] A short list would include the laments of Greece, Ireland, Bolivia, Papua New Guinea, India, Chile, Brazil, Nepal and Finland. I discuss issues in world lament traditions in Performing Grief, Introduction.

[15] This is true for some other lament traditions in China. In modern Chinese scholarship laments are regarded as ceremonial songs (yishige 儀式歌), but this is a latter day interpretation.

[16] In the same way that the sound of weeping and bird calls are intrinsic to Kaluli laments, see Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping and Poetics, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

[17] Nanhui laments borrow imagery from the rich repertoire of Wu songs common to the lower Yangzi Delta region. Other Chinese regional traditions are discussed in detail in Chapter 5, Performing Grief.

[18] Bauman, 'Verbal Arts as Performance,' p. 305.

[19] For parallels with the Hong Kong and Pearl River bridal lament tradition see Rubie S. Watson, 'Chinese bridal laments: the claims of a dutiful daughter' in Harmony and Counterpoint: Ritual Music in the Chinese Context, ed. Bell Yung, Evelyn S. Rawski and Rubie S. Watson, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996, pp. 107–29; also Elizabeth L. Johnson, 'Singing of separation, lamenting loss: Hakka women's expressions of separation and reunion' in Living with Separation in China: Anthropological Accounts, ed. Charles Stafford, London & New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, pp. 27–52.

[20] Discussed in detail in Performing Grief, Chapter 6.

[21] For discussion see David I. Kretzer, Ritual, Politics and Power, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1988, pp. 37–38.

[22] 'Ritual and resistance: subversion as a social fact,' in Contesting Power: Resistance and Everyday Socal Relations, ed. Douglas Haynes and Gyan Prakash, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992, pp. 213–38.

[23] McLaren, 'Mothers, daughters.'

[24] The young village woman would have viewed lament performances from earliest childhood. Mothers taught daughters the 'discourse of subordination' in the first stage of the lament and presumably in everyday life situations, see discussion in McLaren, 'Mothers, daughters.'

[25] Debra Skinner, Dorothy Holland and G.B. Adhikari, 'The songs of Tij: a genre of critical commentary for women in Nepal,' in Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 53, no. 2 (1994):259–305, p. 301, note 27. I have also found instructive the following study of Debra Skinner, Jaan Valsiner and Bidur Basnet, 'Singing one's life: an orchestration of personal experiences and cultural forms,' in Journal of South Asian Literature, vol. 26 (1991):15–43.

[26] Discussed in detail in Performing Grief, Chapter Two.

[27] See McLaren, 'Marriage by abduction.'

[28] This lament cycle comprises some 1,500 lines in numerous sections, reproduced in Ren, Hunsang. The transcript is based on a recording made by a performance elicited of Pan Cailian in the early 1980s by members of the Cultural Bureau, Nanhui. Pan's lament cycle, while believed to be typical of the Nanhui style, is not necessarily representative of Chinese bridal laments in general. This study should thus be understood as an analysis of one regional tradition in China. The laments of the Pearl River Delta are distinct in content from those of Nanhui, see discussion in Chapter 5 of Performing Grief. For reasons of length, excerpts from Nanhui laments are not given here. For excerpts relating to this discussion, see Performing Grief, esp. Chapter 4.

[29] A partial translation of Pan Cailian's bridal lament cycle is provided in the Appendix of Performing Grief.

[30] Increasingly in urban areas of nineteenth century Songjiang, foundling homes were made available for orphans. But the lament community in Nanhui was located far away from these places and transport was very inconvenient.

[31] 'Filling the Box,' lines 473–75, in Ren, Hunsang, p. 28.

[32] This makes the situation radically different to that of a teenager in the West throwing a similar tantrum in front of their parents. Infanticide was part of the everyday experience of many Chinese communities in pre-modern times.

[33] This was on a trip to Nanhui in June 1999, accompanied by my chief collaborator, Professor Chen Qinjian of East China Normal University, Shanghai.

[34] Kathy Le Mons Walker, Chinese Modernity and the Peasant Path: Semicolonialism in the Northern Yangzi Delta, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999, p. 193.

[35] Hill Gates, China's Motor: A Thousand Years of Petty Capitalism, Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1996, pp. 142–45.

[36] Cited in Gates, China's Motor, p. 143.

[37] Cited in Gates, China's Motor, pp. 143–44.

[38] McLaren, 'Marriage by Abduction,' pp. 967–968.

[39] Gates, China's Motor, p. 124.

[40] Walker, Chinese Modernity.

[41] Lynda S. Bell, 'For better, for worse: women and the world market in rural China,' in Modern China, vol. 20, no. 2 (April 1994):180–210.

[42] Hill Gates, 'Footloose in Fujian: economic correlates of footbinding,' in Comparative Study of Society and History, vol. 43, no. 1 (2001):130–148, p. 131.

[43] See particularly McLaren, 'Women's work,' p. 799.

[44] Hill Gates, 'The commoditization of Chinese women,' in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 14, no. 4 (1989):799–832, p. 799.

[45] Susan Mann, 'Grooming a daughter for marriage: brides and wives in the mid-Qing Period,' first published 1991, reprinted in Susan Brownell and Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom (eds), Chinese Femininities Chinese Masculinities, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, pp. 93–119; Patricia B. Ebrey, Confucianism and Family Rituals in Imperial China: A Social History of Writing about Rites, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991, p. 82.

[46] Ebrey, Confucianism and Family Rituals, p. 83.

|