Hearing Women's Voices, Contesting Women's Bodies

in Post New Order Indonesia

Barbara Hatley

Introduction—women in the spotlight

-

Over the last decade in Indonesia there has been a striking increase in the public presence of women. Sexualised display of women's bodies, already flourishing in the mass media boom of the 1990s, has expanded further with the relaxation of the ideological restrictions and media controls of the Suharto era. Women authors, once a rarity in literary circles, now publish prolifically, producing works marked by frank depictions of sexual issues and encounters which have been assigned the collective label of sastra wangi, 'perfumed literature.'[1] Vigorous debates of gender issues take place in the mass media. Women have also become more politically involved as women's NGO groups and networks, mobilised in the movement against Suharto, continue their activities into post-Suharto times.[2] Campaigns for greater formal political representation of women resulted in the passing of a law in 2003 recognising the principle that all political parties contesting elections should have at least 30 per cent female candidates.[3]

-

But as intimated in the above description, this new-found female 'prominence' is a mixed phenomenon, shaped by diverse factors—capitalist commoditisation, post-New Order liberalisation of expression, democratisation. It has likewise met with sharply conflicting responses. The popular Islamic movement which has emerged strongly in the post-Suharto years has vigorously attacked the new freedoms of sexual expression in media and society, explicitly targeting women. Representatives of conservative Islamic groups condemn public exposure of female bodies as undermining the moral fabric and traditional identity of Indonesian society. They advocate stricter rules of dress and behaviour for women, and promote 'traditional' Islamic family practices such as poligami, polygamous marriages involving up to four wives.

-

The controversy erupting in 2006 over the proposed anti pornography law, the RUU APP (Rancangan Undang-undang Anti Pornografi dan Pornoaksi—Program of Anti-pornography and Anti-pornographic Action Legislation), gave vociferous expression to conservative and liberal positions on these issues. Brought forward in parliament by Islamic parties in 2005, the law stipulated the banning of pornography both in the sense of sexually explicit visual and written media, and what it termed pornoaksi—public behaviour by individuals deemed to be erotic. Heavy fines and prison sentences were proposed for anyone exposing parts of the body such as the hip or navel, or moving in ways considered sexually provocative.[4] Creative artists, women's organisations, human rights groups and representatives of non-Islamic regions of Indonesia have expressed emphatic rejection of the law, separately and as a combined group. In April 2006, these groups staged a colourful march through the centre of Jakarta, celebrating the ethnic, regional and cultural diversity which the new law would restrict and expressing their opposition. A month later, a million-strong rally of supporters of the bill was held in response. Conservative Islamic groups have been the most vocal and prominent supporters of the law, on the basis of Islamic prohibitions on exposure of private parts of the body. But more moderate voices, too, express concern about the deleterious impact of pornography in society, especially on young people. Women speak of their difficulties in bringing up children, trying to protect them from the temptations of ubiquitous erotic media. A moral panic rages about global cultural influence eroding national identity and morality.

-

Ongoing delays in the implementation of the anti-pornography law, and a reported reduction in its scope, suggest that, at the national level, the law will not implement monolithic, repressive restrictions on social behaviour.[5] But in various regions of Indonesia, local parliaments have used their authority under the new regional autonomy administrative system to implement such measures as night curfews on women and compulsory wearing of the Islamic headdress (jilbab) by government servants and school children.[6] Meanwhile the force of opinions mobilised by the anti-pornography bill, and the violence directed at liberal-minded groups, have worrying implications for Indonesia's future as a pluralist country. Along with attacks on nightclubs, hotels and the offices of the recently published Indonesian version of Playboy magazine, Islamic activists also targeted women involved in the April 2006 diversity rally. Repeated physical attacks were made on the homes of the rally's organiser, playwright and theatre directory Ratna Sarumpaet, and that of the singer Inul, a prominent participant, along with calls for these women to leave Jakarta. Head of the Islamic brotherhood verbally condemned as 'evil women' the events' organisers, including Siti Nuriyah Wahid, the wife of former president Abdurrachman Wahid. Siti Nuriyah responded with a court challenge.

-

In this context, women's bodies can be seen to serve as a site of social control and an emblem of national identity, as they have done previously in modern Indonesian history. In the late colonial period the concept of the 'modern woman' was valorised by progressive nationalists, while symbolising for conservatives the destruction of revered local cultural tradition. In 1965, a concocted, aggressively sexual image of the Communist women's movement, Gerwani, served to demonise Communism and justify annihilation of its adherents.[7] The demure, decorous image of woman as wife and mother symbolised the social order which Suharto's New Order regime supposedly then restored to the nation.[8] Today the good wife and mother image has arguably been replaced by a plurality of female forms. Uncertainty about the direction of Indonesia as a nation and opposing visions of Indonesian identity are reflected in conflicting, contested images of women's bodies. Moreover, as democratisation facilitates the political involvement of a wide range of social and religious groups, women's bodies become not merely symbols of opposing positions in a discrete, elite-controlled domain of state politics. Instead sexual morality and propriety are real issues of contest at the societal level, with women's bodies as the terrain of struggle placed centre stage.

-

Artists and performers, many of them women, have been actively involved in these contests over sexual expression, women's bodies and national identity. Women writers contribute prominently to the controversy, female media performers are vilified by conservatives as a source of immoral influence and defended by liberals, and the artists, Inul and Ratna Sarumpaet, have been at the centre of the fight. The contradictions of the current situation seem likely to be felt particularly keenly by women creative artists, as new opportunities open up for them to display their skills and express their ideas, while impending restrictions on women's bodily expression and social freedom threaten to take away these gains. In this article, I look at examples from the field of performing arts, at the work of several women directors and their theatre groups. My focus is on the sense of agency conveyed in their creative work—agency understood in the broad, inclusive sense of a heightened ability to interpret subjective experience and social conditions, a sense of self-expression and 'capacity for identity and meaning- making.'[9] Agency more narrowly defined as active resistance to dominant discourse, though not explicitly expected in their performances, might also find expression.

-

Suzanne Brenner, Nancy Smith Hefner and Lyn Parker have analysed the sense of agency experienced by young women in contemporary Indonesia in adopting the wearing of the jilbab Islamic headdress. Young women university students in particular, taking up opportunities for higher education in big cities, faced by the confusing diversity and temptations of urban life find 'a heightened self-confidence and moral self-control'[10] in adopting the jilbab, 'a sense of self-mastery and identity in a time of great social flux.'[11] Lyn Parker in her article in this issue of Intersections reports on the confidence in their moral purity experienced by young jilbab-wearing women and the respect and approval they receive from others. Such examples are unlikely to have much relevance, however, for the vast majority of female performers.[12] On the whole they come from backgrounds of less strict Islamic practice. The Javanese performing arts, characterised by pre-Islamic stories and cultural norms, have long been cultivated among religiously-syncretic communities. Modern Indonesian language theatre, originating among students at secular, Western-style schools, remains associated with liberal attitudes and lifestyle. Young women in jilbab participate in campus theatre at Muslim universities, but their numbers are relatively small. Instead, as noted above, many women performers join protests against the imposition of strict Islamic morality and some have even been attacked by radical Muslim groups. To what extent are such experiences reflected in their performances? How does their work reflect on women's perception of and response to social changes? What differences can be seen in the type of agency expressed in different theatrical genres and by individual performers?

-

One site for the investigation of agency might be the number of women theatre directors and all women performing groups. Women have long participated in the rich variety of performance genres cultivated in different areas of Indonesia, as singers, actors and dancers in mixed-sex groups directed by men. However the phenomenon of single woman performers or all-women groups, such as in Balinese arja, was very rare. In modern theatre groups, dominated by male directors, performing written scripts authored by men, women actors arguably had less autonomy than in traditional forms and women directors were virtually unknown.[13] Over the last ten to fifteen years, however, women-only groups have emerged in a number of traditional, regional theatre genres and increasing numbers of women are directing performances of modern, Indonesian-language theatre. The following discussion reviews women's participation in Indonesian theatre in recent years in two performance genres, the Javanese popular theatre form ketoprak and modern Indonesian-language drama. I look at the work of a number of women directors who represent women's bodies in innovative new ways, challenging traditional cultural stereotypes, and at a play by Ratna Sarumpaet Pelacur dan Sang Presiden (The Prostitute and the President), which explicitly addresses issues of morality, religion, politics and women's bodies.

All women performances

-

Visiting the Central Javanese city of Solo in 2004, I was surprised to learn about an all-woman ketoprak show directed by a woman actor to celebrate Indonesian Independence Day. Previously I had heard of all-women ketoprak only as entertainment staged by the inmates of a women's prison, never in commercial performances, nor as part of the participatory concert held in villages and urban neighbourhoods to mark Independence Day. Several researchers on traditional theatre genres in Bali have reported on the increased incidence in recent years of the formation of women-only groups. Now, not only the genre arja but also topeng (masked dance drama), cak (chanting) and even ritual performances of Calon Arang are performed by women's groups.[14] In Java, too, it seemed, things were changing.

-

The production of Suminten Edan (Suminten goes crazy) directed by veteran actor, Bu Milko, with a group of her neighbours was clearly great fun for all—the housewives, school girls, street vendors and other women who made up the cast, and audience members who knew the actors in daily life. Bu Milko and another experienced, middle-aged woman performer took the parts of two warok, rural strong men; the story depicted the daughter of one of them going mad when jilted by her nobleman fiancé, who takes up instead with the daughter of the other. Wearing thick moustaches and beards, Bu Milko and her companion swaggered around the stage, issuing orders in low rasping voices, and smoked cigarettes with gusto. The role of mad Suminten was played by a hugely tall, bulky young woman in a bizarre outfit with items such as rubber thongs attached to it. Her erstwhile fiancé wooed 'his' new love passionately, with greater licence than would be possible for a mixed-sex couple on stage. The ineptitude in martial arts of the teenage girls playing the waroks' troops simply added to the humour of the show. The performance ended with the whole cast gathering onstage, shouting Merdeka! (Freedom!) and singing the Indonesian national anthem.

-

This finale might be said to sum up symbolically the nature of the event—a group of women working together enthusiastically to contribute to their community and nation. In a similar way to the all-women groups which have recently begun to perform in Bali, the aim seemed to be above all to show that women can do it too; they can dance, sing, act, joke and entertain. The post-Suharto politics of democratisation and regional autonomy arguably encourage local, community participation in ways which have opened up new spaces for women to perform.

-

Indeed in early 2006 came news from the nearby city of Yogyakarta regarding the formation of a professional all-women's ketoprak group, Kartini Mataram. The troupe had been formed partly to provide its members, many now middle-aged, with a medium of expression.[15] Another aim cited by the troupe leader, a famous comedienne, Yatie Pesek, was that of encouraging gender equality, promoting the message that men as well as women have the right to determine their life choices.[16] At the end of their first performance in April 2006, celebrating Kartini Day, the group invited onstage Dyah Suminar, wife of the Yogyakarta mayor, who gave a speech on women's issues including domestic violence and polygamy. Kartini Day 2007 was again marked by a performance by the group. Their shows follow the format of existing ketoprak lakon, highlighting inbuilt gender references. Their novelty lies in the bringing together of women performers to contribute collectively to the artistic life of Yogya.[17] Rather than retreating from the stage into grandmotherhood, as women performers of their age would have done in the past, the senior women of Kartini Mataram are taking centre stage.

-

Ketoprak and other regional theatre forms show women holding their own, increasing the space of their activity within the boundaries of established convention. A sense of agency is expressed in their confident assumption of male roles in shows performed independently of men. Practitioners of modern theatre, meanwhile, are able to go further, using original texts and exploratory approaches to create stage imagery unconstrained by traditional theatrical patterns, potentially conveying alternatives to established social values. Women directors, their numbers increasing significantly in recent years, have made use of these opportunities to present novel constructions of women's bodies and identities. Since the mid-1990s, I have been following the work of a number of such women directors, some of whom were previously actors in male-directed groups but now head groups of their own.[18] While the themes and dramatic images of their productions are diverse, arguably reflecting varying responses to women's social experience, all engage in some way with cultural 'tradition' and its problematic implications for women.

The woman worker's body – strong, capable, resistant.

-

Margesti, director of Teater Abu, an acronym for Teater Aneka Buruh (Theatre of all kinds of workers), was a star performer of the avant garde group Teater Sae before being invited by a women's NGO in the early 1990s to help establish a theatre group among factory labourers on the outskirts of Jakarta. After several moves and restructurings, Teater Abu now comprises both factory workers and other residents of the area where Gesti lives—petty traders, informal sector workers and housewives. The earlier productions of the group, when all members were factory workers, focused specifically on workers' issues. Later performances have depicted women's experience more generally. Perempuan, for example, staged to celebrate Independence Day 2000, engages with the theme of domestic violence, depicting a husband aggressively threatening his wife, the woman vigorously resisting, then a chorus of women moving across the stage, spreading their arms, punching the air and chanting defiantly Kita harus membuat sesuatu! Kita harus membuat sesuatu! (We must do something! We must do something!).

-

A 2004 production Mereka Bilang Aku Perempuan (They say I'm a woman), again indicated women's strength and capabilities, along with the challenges of their lives. Several middle-aged women in factory-style protective clothing push heavy metal barrels around the performance space as two younger women in shorts and T shirts race frenetically back and forth, leaping over the barrels, with irons in the their hands, ironing the air. Male performers, dressed for relaxation in sarongs, whistle to unseen song birds, play flutes and toss around a soccer ball. Women can and do perform all kinds of jobs—in factories, performing domestic tasks; men play. In a later scene the issue of domestic inequality is directly, yet humorously, addressed. As a group of women wash clothes, scrubbing them in a soapy lather on the ground, one of them hurls something wet and soapy into a group of male viewers. 'Here, wash your child's shirt!' she yells, to hearty laughter from the audience. Later, however, the strains of women's pressured existence, as workers and wives, are graphically symbolised as one of the young woman performers leaps astride one of the big iron barrels, now full of water, plunges into the barrel, repeatedly surfacing, then disappears again. In a more recent performance fragment, entitled Siti Nurbaya Lari-lari (Siti Nurbaya on the Run), the same actor, Liswati, takes on the persona of the modern Indonesian woman, attempting to break free of the bonds of tradition but bombarded by the choices of modernity. Margesti, as an older woman in traditional Javanese dress, personifies 'tradition,' scolding her younger counterpart for overly free behaviour, incorporating her into household rituals. Once again the performance ends with Liswati astride the water barrel, plunging into the water, leaping out in bold assertion, but finally sinking, overwhelmed, defeated.

Embracing cultural 'tradition'

-

While Teater Abu represents 'tradition' as a commanding, somewhat threatening older woman, members of the group Sahita take on the personae of aged women dancers to embrace Javanese cultural tradition and to subvert it from within. Based in the court city of Solo, with its strong heritage of Javanese aristocratic tradition, the group performs the female court dance srimpi, traditionally presented by young daughters of the nobility, embodying ideals of refinement, grace and feminine beauty. But here the dancers are depicted as grey-haired, wrinkled and bent-backed, old village women on their way to market in the pre-dawn hours, with rolled up mats on their backs and little lamps in their hands. Sahita's leader, Inonk, previously played the role of wise old grandmother in the plays of the theatre group Gapit, depicting the struggles of underclass Javanese communities to survive in the age of development. Gapit ceased performing in 1997 after the tragic death of its director, but Inonk has maintained the legacy of its strong, resilient old women in innovative dance and drama performances, devised collaboratively with the four other members of the group. These collective processes helped inspire the name Sahita meaning togetherness. Improvising dialogue and movement, teasing one another, letting their imaginations flow, is something the performers enjoy greatly, feeling released like real-life village grannies from the rules of feminine decorum and modesty constraining younger women.

-

The sense of fun and freedom in playing the parts of old women connects with one of the key themes of the group's work—challenge to the dominance of youth and beauty as constraints on women's activities and standards for judging their worth. In dance, particularly refined court dance, focused on the beauty of female bodily form, such standards are paramount. Very often women give up dancing publicly by their late twenties, out of shame at perceived imperfections of physical form. Sahita's representation of unambiguously old and imperfect female bodies performing the most iconic of court dances challenges these restrictions, symbolically claims space for ordinary women's bodies. Another major theme of Sahita performances is assertion of underclass village and kampung identity. For the dress, demeanour and speech of the dancers marks them out very clearly as lower class. Some see Sahita's work as rebellious, subverting the aesthetic codes of court dance, and the refined, graceful image of palace womanhood. But Inonk and the other performers describe what they are doing simply as membumikan srimpi, bringing srimpi down to earth, making it part of the practice of ordinary people.

-

In later performances, the earthy, comic potential of the old women figures is developed in dialogues and role plays which comment on contemporary social issues. As professional female dancers, ledek, with erotic movements contrasting comically with their white hair and wrinkled faces, the dancers make reference to male sexual harassment. When Inonk, as prim 'group mother,' asserts that respectable audience members never touch dancers' breasts, another performer retorts 'No, they suck them instead.' Aja dhemok pentilku (Don't touch my nipple), the others sing, to Inonk's consternation, and delighted laughter from the audience. The humorous persona of the dancers arguably allows the voicing of views not possible for pretty young dancer/singers, vulnerable to and fearful of hostile male reaction.

-

Sahita's vision of a more liberated female identity employing the medium of Javanese dance, music and wayang mythology suggests the ongoing symbolic power of these elements, while rendering them more inclusive, more 'down to earth.' Everyday Javanese womanhood is celebrated within a familiar frame. The relative comfort of this fit distinguishes Sahita's approach from that of other female performance groups which invoke traditional theatrical imagery more combatively, challenging and negating long-standing myths and archetypes.

Resisting age-old myths

-

The Balinese writer and performer Cok Sawitri, for example, has re-presented the figure of Calon Arang, the evil widow witch of Balinese and Javanese legend and performance, as political victim and as an original female deity, silenced and excluded by male power holders. Cok's engagement with the figure of Calon Arang began with her monologue Pembelaan Dirah in 1996, in which Calon Arang or Dirah, (the name of her home area) recounts, in fierily resistant terms, attacks on herself and her followers by soldiers of a powerful king. Evoked here is both the mythical struggle between Calon Arang and king Airlangga of tenth century Kediri, and that of a contemporary woman leader, Megawati, and her PDI (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia) political party, confronting the might of the Suharto regime. For Cok recounts being deeply shocked and angered by the attack on the headquarters of Megawati's PDI political party in July 1996, an event she saw as symbolising the suffering of the nation under brutal power holders. With tousled hair, black-rimmed eyes, and red-painted mouth, singing eerily, Cok's image is both menacing and mesmerising, as she recounts the story of the destruction of her hermitage by thousands of soldiers, yet her refusal to respond with violence to avoid further bloodshed, just as Megawati offered moral and legal challenges but no physical resistance towards the Suharto regime.

-

More recently, working with her theatre group Kelompok Tulus Ngayah, Cok has portrayed Dirah/Durga as the embodiment of the female creative principle in performances with a meditative ritual. In a 2004 performance, Cok as narrator described in esoteric old Javanese how the female deity, essence of goodness, used the sacred symbols of the Balinese alphabet to define human beings and their inter-relationships. Three white-clad, white-masked woman dancers, representing the female deity, slowly traced letters in the air, then sank to the floor. The text recounted how power holders refused to allow the story of female creation to be told. Instead the goddess was banished to the margins as priests defined the directions and locations of the world.

-

Cok Sawitri, deeply involved in spiritual practice and knowledgeable about its traditions, challenges hegemonic Balinese mythology on its own terms. By contrast Shinta Febriany, a young Makassar-based playwright and director, depicts ideological 'myths' through jarring imagery suggesting distance and alienation. Archetypal gender stereotypes are presented in startling new ways. In her production namaku adam tanpa huruf capital (My name is adam without a capital letter), male actors race about the stage performing domestic tasks, their bodies buttered and floured like cakes, and a huge penis moulded out of butter, embodying the concept of male household head, is adorned with a sparkling firework like a candle on a cake, celebrating men's liberation from constrictive masculine roles. In a follow-up performance Hawa dari Bawah Tanah (Eve from underground), female performers with shaven heads and overweight bodies, wearing the costumes and headdresses of the traditional Sulawesi dance form pakarena, challenge and confront the traditional constructions of graceful womanhood.

Comparing images, analysing strategies

-

Amidst the diversity of styles and characters in these female-directed performances there are intriguing parallels and thematic correspondences. Teater Abu's women activists and Cok Sawitri's Calon Arang, each in their own ways, confront political order. Cok and Shinta engage with myth and ritual, Cok seriously and reverently, Shinta with satirical humour. Sahita's playful, passing reference to sexual harassment becomes forceful assertion in Teater Abu's graphic portrayal of domestic violence. Another shared concern is that of domestic hierarchy and the burden of women's work—a site of angry protest symbolised by hurled wet washing in Gesti's Mereka Bilang Aku Perempuan, and of humorous subversion, as males perform female tasks and are evaluated as sex objects in Shinta's namaku adam. Shinta's work and that of the Sahita group both invoke satirically the image of female dancer, rejecting the construction of women's identity in terms of their youth and beauty that the image represents. Overwhelmingly, 'tradition' is portrayed as a site of restriction and inequality for women, albeit operating through diverse dramatic idioms.

-

A further common characteristic of the performances reviewed above is their focus on the creation of bodily images of male and female rather than the development of a dramatic narrative. Exchanges of dialogue are brief, with verbal communication more often occurring as monologue, poetic speech fragments and song than extended discussion. Western feminist theatre analysts suggest that such fragmented, non-realistic approaches provide greater room for the expression of female experience than the realistic play, with its restrictively patriarchal form.[19] The Brechtian strategy of estrangement through incongruous imagery, subverting standard expectations of narrative and character, highlights the 'constructedness' of gender stereotypes.[20] Such approaches probably arose out of the theatrical experiences and resources available to the directors, rather than as purposeful feminist choices, but they have allowed the development of imaginative alternatives to established gender stereotypes, a celebration of new possibilities.

Realist plays and political witness – Ratna Sarumpaet

-

Women directors of realistic plays have attracted less public attention, partly because the constraints of a written script and set dramatic format work against the expression of new perspectives. One woman, however, stands out as a writer and director of such plays, as well as a political campaigner and prominent cultural figure—Ratna Sarumpaet. Ratna had directed a number of plays with her group Satu Merah Panggung, before she achieved national and international fame in the mid 1990s with her plays concerning the fate of the murdered worker Marsinah. Involvement in the campaign against Suharto in 1998 saw Ratna imprisoned for several months, and released only with Suharto's fall. Her next project took her to the province of Aceh, torn by civil war between the Indonesian army and local separatists, and the writing of a play about a woman caught in the midst of the struggle, Alia. Next followed at play about the suffering of families of victims of the 1965 anti-communist killings and imprisonments, Anak-anak Kegelapan (Children of Darkness). And in 2006, following her attack by Islamic extremists in the context of the anti-pornography controversy, Ratna wrote and staged Pelacur dan Sang Presiden, confronting the hypocrisy of political and religious leaders who blame women for the immorality arising from their own corruption and neglect.

-

Several of the other women directors mentioned above responded artistically in some way to the anti-pornography legislation debate. Most notably, Cok Sawitri presented a collaborative movement piece with an American male dancer entitled Open, celebrating intercultural communication and reinforcing her political activism in defence of Bali's pluralist, inclusive culture.[21] But in contrast to the symbolic or playful reference to actual events and issues in other performances, Ratna's play conveyed direct, literal commentary—agency in the narrower sense of explicit resistance to dominant discourse. We might ask what kind of bodily image of women Ratna's play presents, in comparison to the works of the other female directors, and what it may symbolise.

Ratna's play was initially inspired by a request from the international agency UNICEF to write a play about underage sex-trafficking. Travelling around Indonesia to conduct research on this problem, she became aware of its depth and complexity, and of connections with wider flaws in state policies and religious morality—the preference for instant solutions and shallow slogans rather than thoughtful, thorough approaches. Her play focuses on the figure of a prostitute, Jamilah, sexually exploited from an early age, tricked into prostitution, who has surrendered to police after killing one of her clients, a government official. Sentenced to death for her crime, she claims the right to a final wish—to be allowed to meet with a kiai, a Muslim religious leader, and with the President of her country. For the religious leaders are the ones with responsibility for maintaining morality in society, while politicians should eliminate corruption and build strong, accessible state institutions. In her own case, and that of millions of exploited women and children like her, both state and religious leaders had failed.

-

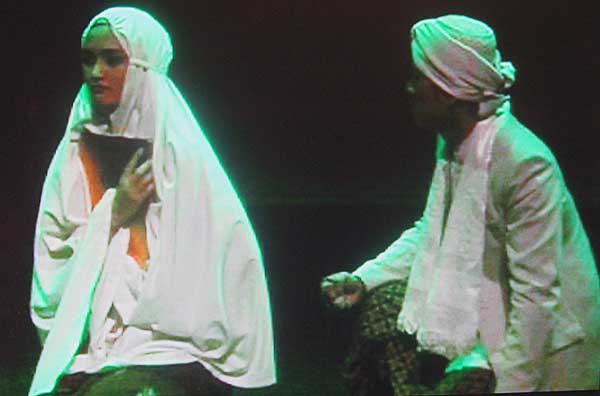

The role of Jamilah is played by Ratna's daughter, tall and slim like her mother, athletic and assertive. Ratna herself plays the prison guard, Bu Ria, initially fiercely hostile towards Jamilah but eventually supportive and protective. The constant motif in Jamilah's representation is that of violation and resistance. Two separate spaces onstage depict her current situation and play out the harsh events of her past. We first see her clad a white jilbab, praying, in the 'respectable' home to which she was entrusted as a child to save her from child prostitution. But her adoptive mother is outraged to see her praying, regarding her as a devil (setan), because of her pregnancy and refusal to reveal whether the husband or son of the family is responsible (in fact both have raped her). So Jamilah removes the jilbab from her head, with a look of combined sadness and anger, but still refuses to tell. Later, in the prison where she is awaiting execution, she is verbally abused and seized roughly by the hair by Bu Ria, and shoved and pulled by the prison guards. But she also exposes her long legs to the prison guard, taunting and teasing him, and fights back when two wives of government officials, visiting her in prison, attack her. Flashbacks to Jamilah's former life in an isolated prostitution complex have shown sex workers mockingly confronting raiding police. Outside her present prison cell huge crowds, mobilised by the Forum Pembela Iman Bangsa (Forum of Defenders of the Faith of the Nation), a transparent reference to the Islamic group FPI, (Forum Pembela Islam Forum of Defenders of Islam) which had victimised Ratna herself, are shouting demands that Jamilah must die. Jamilah and other characters comment on the hypocrisy of their actions, carrying weapons, threatening violence in the name of religion. But the menacing shouts continue.

Figure 1. Jamilah taunting and teasing an angry prison guard in Pelacur dan Sang Presiden. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

Figure 1. Jamilah taunting and teasing an angry prison guard in Pelacur dan Sang Presiden. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

|

Figure 2. Wife of government official confronts Jamilah. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

Figure 2. Wife of government official confronts Jamilah. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

|

-

At the end of the play Jamilah, confronts the kiai summoned at her request. Although wearing a white jilbab prayer garment she feels too burdened with anger and shame to be able to pray. Refusing the kiai's invitation to join him in prayer, she instead tells him her horrific life story, beginning with her father's plan to sell her into prostitution as a baby in keeping with common practice in his region. It is this sort of evil religious leaders should be working to change, rather than lecturing people about morality, making religion frightening, and legitimating hatred and killing. Why was he not there for her earlier in her life when she needed help? Why? Why? Then she rips off her white jilbab, and orders him to look at her. Dirty and abused as she is, she is his responsibility. In the final moments of the play the silent figure of the President appears at the back of the stage, standing between Jamilah's executioners, as she asks the questions 'Who wanted me to be a prostitute?' 'Who soiled me?' 'Who piled up hatred in my heart?'

Figure 3. Jamilah and the kiai in final scene of the play. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

Figure 3. Jamilah and the kiai in final scene of the play. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

|

-

Although perhaps exaggeratedly dramatic, the play has a powerful impact. Its indictment of religious and political authorities for their hypocrisy in issues of sexual morality comes through loud and clear, and the immediacy of connection with real-life conditions gives added force. Jamilah as wronged, abused woman is admirably strong, intelligent and defiant. Yet as she faces death, soiled by her experience, distanced from her religion, her angry accusations receive no response. The picture of conditions for exploited sex workers, the plight of women in general as moral targets and the state of Indonesian society and nation is bleak. No solution is suggested. Indeed Ratna states in introductory notes to her play that she offers no way out, her aim is simply to open viewers' eyes to the problems of amorality, poverty and ignorance facing Indonesia, and the roles of political and religious leaders in perpetuating these. As it engages directly with current social problems and boldly challenges hegemonic discourse, Ratna's play conveys a mood of anger, frustration and alienation.[22] The bleak social vision of this work accords with reports of the responses of women activists to the current struggle between liberal and conservative forces in Indonesian society. In place of the increased freedom they had hoped to enjoy with the dismantling of the authoritarian New Order political regime, a much larger and more pervasive challenge faces them at societal level in the rise of conservative, repressive Islam. [23]

Concluding thoughts

-

The performances reviewed above reveal women's lively, innovative contributions to their local theatre scene, connoting increasingly confident social participation by women. Their work expresses agency both in the sense of new self-confidence and independence in performing conventional roles, and in the case of several modern theatre directors the creation of novel images embodying alternate perspectives to dominant gender ideology. In the one case of explicit resistance to hegemonic discourse, Ratna Sarumpet's challenge to current religious and political power holders, the mood is defiant but less buoyant, less certain. In this contrast one might see a distinction between a contained domain of artistic exploration of gender and identity, where female perspectives are confidently asserted, and the wider world of direct political struggle experienced as disempowering to women. One last example, however, somewhat complicates this distinction.

-

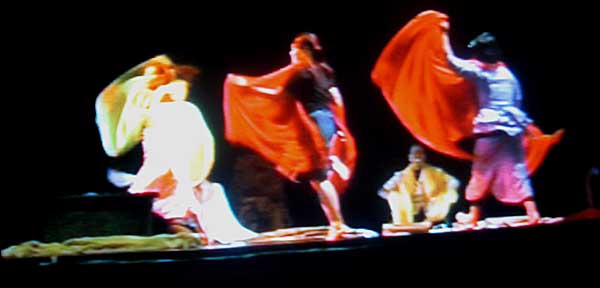

Ratna Sarumpaet's play Pelacur dan Sang Presiden was staged at a conference of the organisation Women Playwrights International that I attended in Jakarta in November 2006. At the same conference another play about trafficking in women, Gerhana-Gerhana (Eclipses), was performed not by professional actors but members of a Surabaya-based sex workers collective. In contrast to the artistic sophistication of Ratna's production their show was folksy, humorous and exuberant. Two narrators in the style of traditional clown figures introduced the theme of unscrupulous agents who promise young village girls all kinds of employment in the city, but instead recruit them into prostitution. The slower of the pair has to have the meaning of 'trafficking' spelled out to her, but claims to be quick enough to spot a good-looking man in the crowd. 'Where? Where?' her companion responds, peering into the audience. Lively group singing and dancing, with brightly-coloured dance scarves, introduces the village scene. The clown/narrators, taking on the role of agents, promise improbable luxuries to the new recruits. 'Why just to get to the market you'll be able to go by plane!" they announce. As they talk of coming from Surabaya to Jakarta to attend a prestigious conference one expects comment on their own experience of plane travel. But no, they had to make the journey by third class train, sleeping on the floor, they report, in an apparent slur on the meanness of the conference organisers. The story ends tragically, with the death from a botched abortion of one of the prostitutes, as a warning of the dangers of listening to the blandishments of trafficking agents. Yet the overall mood of the show was in no sense gloomy, instead happily celebratory. The anger, shame and guilt of the prostitute character Jamilah in Ratna's play was nowhere in evidence. The actors had clearly greatly enjoyed the opportunity to perform, to display their skills, to contribute to such a prestigious event. They report that in general theatre participation gives them increased confidence, awareness, the opportunity to speak out, to 'criticize while uttering jokes at the same time.'[24]

Figure 4. Actors perform lively between-scene dance in Gerhana-Gerhana. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

Figure 4. Actors perform lively between-scene dance in Gerhana-Gerhana. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

|

Figure 5. Sex-traffickers recruiting village girls with tempting tales of city life. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

Figure 5. Sex-traffickers recruiting village girls with tempting tales of city life. Still taken from video-recording of performance made by author.

|

-

Here were ordinary women, members of a lowly, disenfranchised social group, directly and confidently engaging with the political issue of trafficking in women. As the big players struggle to define Indonesia's social identity in gendered terms, as Ratna Sarumpaet invokes the medium of theatre to assert her forceful political critique, ordinary women can be seen using the opportunity of increased attention to their situation to speak out, tell their stories. In some cases their self-assertion may be direct, political, in others symbolic. Although some women performers acknowledge the possible impact on their creative freedom if the stricter moral and behavioural controls favoured by fundamentalist groups were imposed, their work shows no sense of fear or threat. For the present Indonesian women involved in theatre, from avant garde directors to housewives' ketoprak groups to prostitutes' collectives, are revelling in the chance to have their say, represent their reality, participate. The sense of agency they express is diverse, varied and dynamic, celebratory rather than combative.

Endnotes

[1] An extended discussion of the phenomenon of sastra wangi, including analysis of the varied ways the label has been interpreted and applied, can be found in a special journal issue focussing on this topic, Review of Indonesian and Malayan Affairs, vol. 41, no. 2 (2007).

[2] At the beginning of 1998, as the economic crisis hit with soaring prices of household goods, the group Suara Ibu Perduli (Voiced of Concerned Mothers) drew on traditional stereotypes of womanly identity, of women as mothers of the nation, to protest at the failure of the state to provide sustenance for its citizens. Their highly publicised action was accompanied by widespread grass roots mobilisation of women, which has been maintained in the post-New Order period in networks of regional NGOs. See Melani Budianta, 'Plural identities: Indonesian women's redefinition of democracy in the New Order era,' in Review of Indonesian and Malayan Affairs, vol. 36, no. 1 (2002):35–50.

[3] Susan Blackburn, Women and the State in Modern Indonesia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 227.

[4] For a detailed listing of the behaviours classified in the bill as pornoaksi and the substantial monetary fines proposed for offenders see Pam Allen, 'Challenging diversity?: Indonesia's anti-pornography bill,' in Asian Studies Review, vol. 31, no. 2 (June 2007):101–16.

[5] After many months with no official news of its progress, in September 2007, the President instructed the original committee entrusted with redrafting the bill after public consultation to report to Parliament within a specified time. The vice chair of the committee is reported as saying, however, that no speedy implementation of the law can be expected given the deep divisions in Indonesian society concerning the issues contained there.

[6] Edriana Noerdin, 'Customary institutions, syariah law and the marginalisation of Indonesian women,' in Women in Indonesia: Gender, Equity and Development, ed. Kathy Robinson and Sharon Bessell, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002, pp. 179–86; Lyn Parker, 'Uniform jilbab: the Islamic headscarf is now compulsory in many high schools,' in Inside Indonesia, vol. 83, (July-September 2005):21–22.

[7] Steven Drakeley, Lubang Buaya: Myth, Misogyny and Massacre, Clayton, Victoria: Working Paper no. 108, Monash Asia Institute, Monash University, 2000; Julia Suryakusuma, 'The state and sexuality in New Order Indonesia,' in Fantasing the Feminine in Indonesia, ed. Laurie Sears, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1996, pp. 92–119.

[8] Julia Suryakusuma, 'The state and sexuality.'

[9] Lyn Parker formulates this definition in her article 'To cover the aurat: veiling, sexual morality and agency among the Muslim Minangkabau, Indonesia,' in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, issue 16, February 2008, online, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue16/parker.htm. On definitions of agency, in relation to other terms such as autonomy and self-determination see Diana T. Meyers, Essays on Identity, Action and Social Life, Oxford, USA Rowman and Littlefield, 2004, pp. xii–xix. For detailed analyses of the meanings and manifestations of agency in Asian countries, including thoughtful critique of the concept of 'resistance,' see Lyn Parker (ed.), The Agency of Women in Asia, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International, 2005.

[10] Nancy Smith-Heffner 'Javanese women and the veil in post-Suharto Indonesia,' in The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 66, no. 2 (May 2007):389–420, p. 402.

[11] Suzanne Brenner 'Reconstructing self and society: Javanese Muslim women and "the veil",' in American Ethnologist, vol. 23, no. 4 (1996):673–97, p. 689.

[12] A partial exception might be seen in the case of two more senior women directors, including Margesti of Teater Abu, discussed in this article, who have started wearing a head covering as they moved into their forties. However the move seems to be a strategic one, to garner greater respect from the community and acceptance for their work rather than an expression of personal religious or moral commitment. Certainly no perceptible change is evident in their creative work.

[13] See Barbara Hatley, 'Women in contemporary Indonesian theatre: issues of representation and participation,' in Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 151, no. 4 (1995):570–601, for a comparison of the roles of women in traditional performing arts and modern theatre, and Lauren Bain, 'Women's agency in contemporary Indonesian theatre,' in The Agency of Women in Asia, ed. Lyn Parker, pp. 98–132, for an extended discussion of the agency of women performers in modern theatre.

[14] See Natalie Kellar, 'Beyond new order gender politics: case studies of female performers of the classical Balinese dance-drama Arja,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, Issue 10, August 2004, online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue10/kellar.html, accessed 30 January, 2007; Rucina Ballinger, 'Women power,' Inside Indonesia, vol. 83, July-September (2005):7-8; and Carmencita Palermo, 'Crossing male boundaries,' in Inside Indonesia, vol. 83, July-September (2005):9.

[15] 'Drama group promotes women's causes,' in Jakarta Post, April 2006.

[16] 'Kesetaraan Jender Seorang Roro Mendut dalam Ketoprak' Gender equality of a Roro Mendut figure in Ketoprak), in Kompas, 24 August 2006.

[17] Newspaper accounts of the first performance report that all actors and all but three of the accompanying gamelan musicians were women. A leading member of the group, Marsidah, BSc, primadonna of Yogyakarta ketoprak in the 1970s, is quoted as saying that the aim was not exclusiveness but simply to 'show to the public that women are as capable as men of putting on such a performance.' See Jakarta Post, 27 April 2006.

[18] For a discussion of the earlier work of some of these women performers see Barbara Hatley, 'Women in contemporary Indonesian theatre.' A fuller analysis of the contemporary work of the groups mentioned here appears in Barbara Hatley, 'Subverting the stereotypes: women performers contest gender images old and new,' in Review of Indonesian and Malay Affairs, vol. 41, no. 2 (2007):173–204.

[19] Such views are summarised in Elaine Aston, An Introduction to Feminism and Theatre, London and New York: Routledge, 1995, and Sue-Ellen Case, Feminism and Theatre, Basingstoke and London: McMillan, 1988.

[20] An influential discussion of Brechtian techniques as appropriate and effective strategies for feminist theatre, much quoted in other studies, can be found in Erin Diamond, 'Brechtian theory/feminist theory,' in The Drama Review, vol. 32 (1988):82–94.

[21] Cok Sawitri has been a leader of Balinese opposition to the anti-pornography legislation, seen as a threat to Bali's Hindu religious culture and its rich performance traditions as well as its tourist industry. She has organised demonstrations, made statements and joined a delegation of Balinese intellectuals and officials who travelled to Jakarta to explain the Balinese position to parliamentary legislators.

[22] In telling contrast to the agentic role of jilbab-wearing for middle class, tertiary-educated young women, for the prostitute Jamilah, the jilbab symbolises a state of tranquillity and purity beyond her reach.

[23] Candra Kirana of the organisation KOMNASHAM Perempuan spoke in these terms in a speech given at the 16th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia, in Wollongong, June 2006.

[24] The quote is from a statement by a member of this group Teater Kerja Berdaya, (Empowerment Theatre Work) cited by its director, Lena Simanjuntak, a skilled practitioner of socially-oriented theatre work, in the program book of the 7th International Women Playwrights Conference, Jakarta, November 1996, p. 46. Lena Simanjuntak likewise directed the performance Suara dan Suara (Voices and Voices), staged by women workers from plantations and fishing communities in North Sumatra, discussed by Lauren Bain in her article 'Women's agency in contemporary Indonesian theatre.'

|