Introduction[1]

-

Shinjuku Boys,[2] released in Japan in 1995, documents the lives of Kazuki, Gaishi and Tatsu, three onabe who work as hosts in an onabe bar in central Tokyo. Kazuki, Gaishi and Tatsu all identify as onabe, an identity that places them outside gender and sexuality expectations for their birth 'sex'—that is, contrary to sociocultural expectations for 'females,' they do not identify as women and they desire women. This positions them on the peripheral of dominant Japanese gender and sexuality divisions that silence both transgender identification and same-sex desire.

-

It is necessary to gloss the term onabe here even though I am of the risk of momentarily fixing what is fluid. A limited number of studies on the intersections of gender and sexuality in the Japanese context discuss the semantics of this term,[3] but very few studies discuss it as a self-referent, or contextualize its use as a self-referent/identity term.[4] Furthermore, even literature of such import as Robertson?s study of Takarazuka—which explores sexual and gender politics in popular Japanese culture—displays the tendency to approach female to male cross dressing and transsexualism with a questioning 'why?' instead of the more demanding 'why not!' The result is the re-creation of paradigms that pathologise female masculinity. This leads Robertson, in her brief discussion of Club Marilyn, to describe the onabe hosts (she refers to them as ?Miss Dandy?, a term popular in the mid 80s to early 90s) as being ?bascially otokoyaku who live their daily lives as men.? Sufficient to say that even a documentary as controversial as Shinjuku Boys succinctly illustrates that the lived experience of onabe hosts is a far more complex negotiation of heteronormative norms than for which Robertson?s description allows. In brief, therefore, I gloss onabe in the following way: onabe identify as non-female (sometimes identifying as men), sexually desire women (transgender women included), and typically cross-dress female to male (FTM). As Shinjuku Boys illustrates, self-identification as onabe does not presuppose identification as a man (or vice versa), nor does it imply exclusive sexual relations with female born women.[5]

-

Shinjuku Boys is a documentary film where scenes of Kazuki, Tatsu and Gaishi at work, at home and on the streets of Tokyo are spliced with interviews. In these interviews, each talks of their experiences of gender, sexuality, and of relationships with lovers and family. Filmed by a non-Japanese team, any discussion of Shinjuku Boys necessarily raises issues of 'foreign gaze,' 'authenticity' and the complexities inherent therein. As fruitful as such a discussion is it remains outside the scope of this paper. Here I focus exclusively on the verbal interactions that comprise Shinjuku Boys. A study of the language of Shinjuku Boys enables a reexamination of gender and language issues as they have been figured in Japanese language studies.

Unraveling the strands of gender, sexuality and language

-

Japanese language and gender studies have developed a firm tradition of linguistic scholarship. Such research has identified synchronic and diachronic differences in women and men's speech in Japan. A critical reading of previous studies, however, alerts us to the tendency for gender to be posited in a framework which privileges heterogender dualism.[6] In this framework, issues of sexuality have been absorbed into a binary of 'female' and 'male' speech articulated by statically gendered interlocutors.[7] In other words, the unspoken assumption guiding the majority of studies is that woman = heterosexual woman and man = heterosexual man. Heterogender bias is particularly clear in earlier commentaries on gender and language. For example, when noting the lack of gender difference in the speech of primary school boys and girls, Kondô writes the following:

They [the girls] don't feel inferior to males and although they've become aware of the opposite sex, the boys in the class are just too immature. There is no particular reason for them to use 'women's language.' However, I was struck once when one [girl] spoke to a boy she liked saying 'Atashi (I) ... na no [that is]. Iiwa [oh, splendid].' 'Women's language' is nothing more than a 'goody-two-shoes' way of speaking to children who are unconscious of gender differences. The girls are waiting for a time in the near future when they will use 'goody-two-shoes = women's language' in front of a boy they fancy.[8]

-

The above quote is problematic not only because it projects onto 'girls' a normative heterosexuality, but also because it conflates notions of gender and sexuality by directly linking one to the other. Kondô implies that all women will eventually employ 'women's language' as an off-spin of heterogender norms. Kondô uses an abstract quote, which has little meaning in its decontextualized state, to underline his point that women's language is motivated by inherent herterosexual attraction. The quote itself, 'Atashi ? na no. Ii wa,' is explemplary of so-called women's speech not because of content but because it contains the first person pronoun 'atashi' and particles 'na no' and 'wa' all linguistic elements traditionally categorised as stereotypically feminine. Examples such as this suggest that in Japanese, as in English, language not of the heterosexist norm has been tabulated and hidden within static groupings of female and male language.[9]

-

In gender and language studies prior to the 1990s, gendered language is more often than not construed within a framework of 'women's language' [joseigo/onna-kotoba] and 'men's language' [danseigo/otoko-kotoba] as produced by speakers of two different sexes. For example, in an early study (Shibamoto) Smith explains her decision to study the sociological variable of sex in the following way:

In this study, the sociocultural variable sex of speaker is chosen for investigation over other candidates such as age, rank, or status of speaker and over a wide range of contextual features on the basis of its unambiguous nature; with the exception of a small minority, which is easy to exclude from the samples, speakers of Japanese are clearly either male or female and make no attempt to mask their gender through speech [emphasis added].[10]

Here (Shibamoto) Smith not only conflates sex and gender, but also maintains that Japanese speakers do not 'mask their gender through speech'—an assumption implying that it is indeed possible to mask gender through speech.

-

Since the early 1990s, however, researchers have come to question the correlation of linguistic forms to the sex of the speaker. The notion of a monolithic women's language [joseigo/onna-kotoba], and consequently the notion of a monolithic men's language [danseigo/otoko-kotoba], has also been contested. Studies have stressed the heterogeneity of language use[11] and traced the historical construction of women's language.[12] As Okamoto states, 'Japanese women's choice of speech styles is a complex process involving the simultaneous consideration of multiple social attributes associated with identity and relationships. Based on their understanding of themselves in specific relationships and contexts,[13] Japanese women strategically choose particular speech styles to communicate desired pragmatic meanings and images of self.'[14] However, the conflation of gender and sexuality continues to remain largely unattended, and the multiple meanings of gendered language use are often simplified.

-

In calling for Japanese gender and language scholarship to address heteronormative gender assumptions, this study adds to the growing body of literature that illustrates the diversity of gendered Japanese language,[15] and studies that address issues of queer agency in Japanese speech.[16] Essential to the analysis are the concepts of gender performativity—'the ritualized repetition of norms' which enable the process of 'being gendered;'[17] and indexicality—'property of speech through which social identities and social activities are constituted by particular stances and acts.'[18] Following Silverstein,[19] gender indexicality is understood as a process of imputation. That is, gender indexes constitute the performance—the establishment and continuation—of gender in everyday contexts.

Language and gender in Japanese—an overview

-

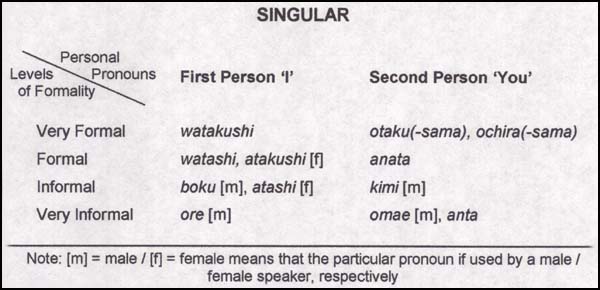

In Japanese, elements of language such as pronouns, sentence final particles and verb inflections are said to constitute gendered language use. In this paper I will concentrate on personal pronouns and sentence-final (or interactional) particles.[20] Personal pronoun usage is generally explained as being dependent on the social distance between interlocutors, the formality of the speech situation and the gender of the referent (see Table 1). In prescriptive accounts, speakers are instructed to use the first person pronouns watashi in formal situations. In casual conversations between social equals, women are expected to use watashi or the more intimate atashi and men boku or the coarser ore.

-

Personal pronouns may be classified as indexicals because their use is dependent on contextual factors and constitutes social identities (e.g. 'woman' 'man') and social activities (e.g. 'formal speech,' 'casual speech.')[21] It is important to remember, however, that although a variety of personal pronouns are available in contemporary Japanese,[22] there is a strong tendency not to use them, especially in the case of third person pronouns.

Table 1. Personal Pronouns in Japanese[23]

Table 1. Personal Pronouns in Japanese[23]

|

-

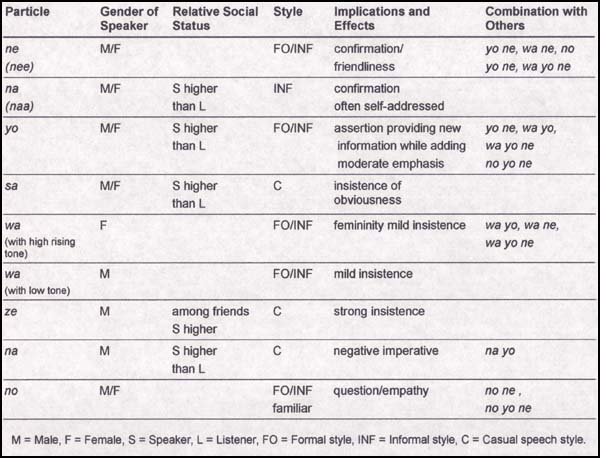

Sentence final particles, also known as interactional particles, occur 'at the end of the main clause and indicate the function of the sentence or express the speaker's emotion or attitude to the hearer in a conversational situation.'[24] These particles are interactive in that they manifest questions, emotional movement, wish etc.[25] and do not contribute to the truth-value of the utterance. Most grammar books outline restrictions on interactional particle use for gender (see Table 2). For example, Makino and Tsutsui write: 'Some of these [sentence-final] particles are used exclusively by male or exclusively by female speakers, so they also function to mark the speaker's sex.'[26] In this prescriptive context, particles such zo, ze and wa (high rising tone) have been labeled as 'gender-exclusive,' a label that risks linking the use of specific linguistic elements directly to the sex of the speaker.

Table 2. Interactional Particles[27]

Table 2. Interactional Particles[27]

|

-

Interactional particles have more recently been reconceptualised in the framework of indexicality. As Ochs states, sentence-final particles such as ze and zo directly index a 'coarse' style of speech and indirectly index 'masculinity.'[28] It is important to stress that linguistic elements such as personal pronouns and interactional particles that have been identified as gender indexes do not, as Ide implies,[29] directly index a speaker's sex/gender. Gender indexicals situate interlocutors in the context of a given speech event and, just as 'few features of language directly and exclusively index gender,'[30] few gendered acts maintain a static meaning over all contexts.

-

I propose that gender indexes are capable of indexing a multitude of social meanings including multiple femininities and masculinities that may both contradict and support hegemonic gender discourses. I focus on two elements of the Japanese language—sentence final forms (mainly interactional particles and combinations thereof) and personal pronouns—in the language use of Gaishi, Tatsu and Kazuki in Shinjuku Boys to illustrate the importance of contextual and discursive analysis of gender indexicals and the multiplicity of genders indexed in language

The language of Shinjuku Boys

-

In the first three scenes of the documentary Shinjuku Boys we, as viewers, are introduced separately to Gaishi, Kazuki and Tatsu: three hosts who work at the onabe nightclub Club Marilyn in Shinjuku, Tokyo. In the first scene Gaishi applies make-up, in the second Kazuki binds his chest, in the third Tatsu discusses hormone injections with his barber. The images effectively underline supposed contradictions in gender image, act and agent. This sequence of three Japanese language scenes is followed by the narrator's commentary in English:

Gaishi, Kazuki and Tatsu all work here at Club Marilyn in Tokyo. All of the hosts here are women who have decided to live life as men. They are called onabe, and for the female customers they are like ideal men.

-

This opening narrative phrase deftly introduces the pivotal concepts of the film, and the societal constructs it hopes to problematise, 'women', 'men', 'female'—and although not overtly stated, 'male.' It becomes clear throughout the documentary that although Tatsu, Kazuki and Gaishi share the same onabe identification and work as hosts at Club Marilyn—a host club staffed by onabe and frequented by a predominately all-woman clientele[31]—each has a different conceptualisation of their positioning within the axis of gender and sexuality expectations for individuals born female. An analysis of language used by speakers in the documentary alerts us to the importance of contextualising gendered language use and attending to the multiple meanings indexed by so-called gender indexicals.

'Kinpatsu wa dame na no' [bleached hair is no good]

-

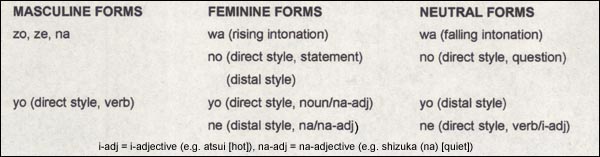

A quantitative analysis of the sentence final particles used by Gaishi, Kazuki and Tatsu in Shinjuku Boys provides an overview of gendered speech patterns—or does it? To pinpoint the downfalls of static interpretations of gender indexing, I will firstly analyze sentence final forms used by Gaishi, Kazuki and Tatsu into 'female,' 'male' and 'neutral' according to traditional classifications of interactional particles.

Table 3. Traditional classification of sentence-final forms by sex of speaker[32]

Table 3. Traditional classification of sentence-final forms by sex of speaker[32]

|

-

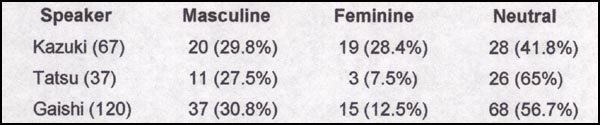

For all speakers 'neutral' forms are the most frequently used, followed by 'masculine' forms and then 'feminine' forms (see Table 4). Of interest is the relatively evenly distribution of 'masculine' and 'feminine' forms in Kazuki's speech. Here I will focus on Kazuki's interactions, in particular on his usage of 'no' which is traditionally classified as a feminine form of mild assertion.[33] Although small in total number, this is the most frequently occurring of the so-called 'female' or 'feminine' sentence final forms that Kazuki uses.[34]

Table 4. Distribution of gender indexicals (individual speakers)

Table 4. Distribution of gender indexicals (individual speakers)

|

-

As Abe outlines, the classification of no as a strongly feminine form is the basis of some contention among gender and language scholars,[35] hence it appears in both the 'feminine' and 'neutral' forms column in Table 3. Any direct correlation between no and femininity is tenuous. In previous research, however, the fact that no nominalises a clause thereby making it indirect has been stated as one reason for it being considered a 'feminine form.' Another reason for this classification is that no posits information as being shared information thereby lessening the distance between interlocutors.[36]

-

There are two contexts within which Kazuki uses the assertive particle no. The first is in his conversations with Sampei, a new host at Club Marilyn, and the second in his conversation with his mother on the phone—their first communication in over a year.[37] Here I will limit discussion to Kazuki's interactions with the new host Sampei to illustrate the problem of directly linking interactional particles in and of themselves with the sex or gender of speaker and projecting that correlation alone onto interlocutors speaking in the real world.

-

Excerpt (1) is taken from a job interview Kazuki and Gaishi conduct with Sampei. During this interview, Gaishi and Kazuki outline the dress code to which hosts are expected to adhere. This is the first scene in which Sampei appears. It is made clear by the narrator and the ensuing interview that he has come to the club looking for work.[38] The sequence opens with Kazuki's comment that blonde hair is not acceptable in the club (kaminoke mo kinpatsu wa dame [na no] [hair, too, blonde is no good]: line 1). Gaishi overlaps with an assertion to the same effect and Kazuki re-asserts stating that totally blonde (that is bleached) hair is unacceptable (line 3). (See Appendices 1 and 2 for transcription notes and conventions and for symbols used in gloss).

(1) kinpatsu wa dame

(Location: Club Marilyn, Interlocutors: G, K, S, Topic: Interview (Hair + Glasses))

|

1

|

K:

|

kaminoke mo kinpatsu wa dame [na no],

hair also blonde TOP bad COP FP

(hair is also not to be blonde)

|

|

2

|

G:

|

[kinpatsu dame,]

blonde bad

(blonde is no good)

|

|

3

|

K:

|

ôru kinpatsu wa dame na no,

all blonde TOP bad COP FP

(all blonde is no good)

|

-

In his second conversational sequence with Sampei, Kazuki questions him on his first night of work (dô datta, haitte, kansô wa [how was it, in there, [as for] your comments?]). Prior to this scene, Sampei (complete with new haircut) has been introduced to the ways of serving drinks and has spent time alone talking to customers.

-

In the excerpt below (2), Sampei gives his impressions of his first night of work.

(2) kiken nan ja nai no

(Location: Club Marilyn, Interlocutors: K, S, Topic: 1st work experience)

|

1

|

S:

|

demo, hito no hanashi o kikanai kedo ne, {LAUGH},

kikanai de yatchau,

but, people LK talk OBJ listen-NEG but FP

(but, I don't listen to people's talk though, do it without listening)

|

|

2

|

K:

|

(tobashichau no?)

skip over:AUX FP

(you skip over them?)

|

|

3

|

S:

|

ee, ki ga,

yeah, mind SUB,

(yeah, my mind ...)

|

|

4

|

K:

|

minna hiichau no?

everyone withdraw:AUX FP

(everyone pulls away do they?)

|

|

5

|

S:

|

ee, hitori dake waratteru toki aru no,

yeah, one person only laughing time exist FP

(yeah, there's times when I'm laughing by myself)

|

|

6

|

K:

|

{LAUGH} abunee janai no, sore, moshikashite,

{LAUGH} risky COP NEG FP, that, maybe

({LAUGH} questionable isn't it, that is, maybe)

|

|

7

|

S:

|

sô ne,

yes FP

(yeah probably)

|

|

8

|

K:

|

kiken nan ja nai no,

dangerous NOM COP NEG FP

(that's risky now isn't it)

|

-

Kazuki's initial response to Sampei's admission of not listening to customers (line 1) is an expansion on the situation with a neutral interrogative no (line 2). He then cuts across Sampei's truncated utterance to clarify how people respond to Sampei's talking (minna hiichau no? [everyone pulls away do they]: line 4). After getting Sampei's admittance that he is sometimes left laughing on his own, Kazuki himself laughs and comments on how 'questionable' that kind of talk is. By shifting from an upward inflected no (line 4), indicating a neutral question, to a downwardly intonated no (line 6), indicating mild insistence, Kazuki also shifts from laughter at Sampei's tendency to dominate conversation without including others to warning Sampei of the danger such action involves. Note here that Kazuki softens the severity of his observation with moshikashite [maybe]. This indicates that Kazuki is merely conjecting, but there is nonetheless still a possibility his conjecture is valid. Kazuki emphasises the 'inappropriateness' of Sampei's actions substituting abunee[39] (lit. dangerous, questionable: line 6) for kiken (lit. dangerous, risky: line 8) in his next utterance.

-

Let me return now to the issue of the repeated classification of no as a 'feminine' gender indexical and the relevance or otherwise of such classification to Kazuki's speech. Given that classification systems employ 'femininity' in terms of heteronormative femininity, and remembering that Kazuki's identification as onabe places him outside of those terms, is it feasible to conclude that Kazuki's use of no in some way indexes and thereby constitutes 'femininity'? Is Sampei collusive in an imputation that would performatively maintain a 'feminine' social persona for Kazuki? The answer is surely negative. In these sequences, Kazuki unquestionably occupies a position as experienced onabe host and Sampei's superior. Only by ignoring Kazuki's self-identification as onabe and his stance could any other analysis be made.

-

The problems inherent with correlating form with gender regardless of context becomes even more apparent when considering the indexical functions of no as a 'group authority marker.'[40] Incorporating Cook's analysis of no as a marker of accessible knowledge, be that knowledge accessible 'because it is common among the members of society,' or because 'it is linguistically and non linguistically disclosed in the speech context'[41] is indicative of the way that Kazuki introduces appearance (not having bleached hair) and customer relations (not talking over people) as knowledge common to Club Marilyn hosts and subsequently as requisite knowledge for Sampei in his new position as a Club Marilyn host. Kazuki's speech is representative;[42] he speaks as part of a member of a group, and in doing so implicates Sampei into that group. He is, therefore, able to simultaneously initiate rapport and exercise influence.

-

Furthermore, given that 'the relevant aspect of the context is made to "exist" ...[43] by indexicals,'[44] then we can conclude that the relevant aspect in this context is the creation of shared accessible knowledge. Henceforth, the issue of gender constitution via the indexical properties of no becomes at the most contextually supercilious. It is because indexicals are constitutive, because they do bring into existence aspects of context, that the shared nature of context is vital to their understanding.

'Ore wa ore dakara [because I'm me]': Self reference and gender

-

Of the three hosts appearing in Shinjuku Boys, Gaishi is most featured in speech scenes throughout the film. In all of his on camera interactions Gaishi self-refers using ore, a personal pronoun, and jibun, a referential (see Table 5).

Table 5. Self Reference

Table 5. Self Reference

|

-

As discussed above, Japanese language studies traditionally classify first person pronouns, according to level of formality and sex (and or gender) of the speaker (Table 3). In this system, ore is classified as a male pronoun.[45] However, as will become apparent in the following, the invocation of 'sex' as an uncontested 'variable' here is inherently problematic, and so too is an interpretation based on this which would presuppose a desire by Gaishi to 'become a man.'

-

Gaishi's use of self-referential ore appears most frequently in situations where he discusses gender (Table 5). However, Gaishi himself specifically states that his intention is not to become a man. In fact, the content of Gaishi's speech reveals that Gaishi's gender perspective is orientated as much if not more towards avoiding classification as a girl. Let me consider an exchange between Gaishi and one of the customers he has a relationship with outside of Club Marilyn. In the following interchange with C1 (a customer), C1 is pressing Gaishi to explain his own gender perspectives.

(3) ore wa ore dakara tte kangaeru

(Location: Gaishi's Room, Interlocutors: Gaishi, C1, Topic: Gender)

|

1

|

C1:

|

ichiô otoko to omotteiru (n) da yo ne,

for the time being man QT thinking (NOM) COP FP FP

(basically, you think of yourself as a man right,)

(1) omotteiru? jibun no koto,

thinking, self LK thing

(you think so?, about yourself)

(1) nan da to omoteiru no? jibun no koto?

what COP QT thinking FP? self LK thing?

(what do you think? about yourself?)

|

|

2

|

G:

|

ore?

me

(me?)

|

|

3

|

C1:

|

un

(yeah)

|

|

4

|

G:

|

un un, nan to mo omotteinai, ore wa ore dakara tte kangaeru,

uh ha, what QT think:NEg, I TOP I therefore QT think

(uh ha, I don't think anything, because I'm just me myself)

|

|

5

|

|

betsu ni sonna ki ni shinai, nani mo

in particular such mind have:NEG, nothing

(I'm not particulary worried, about anything)

|

|

6

|

C1:

|

u:n

(ye:ah)

|

|

7

|

G:

|

betsu ni, dakara onna no ko da to omowanai shi

in particular, therefore girl COP QT think:NEG too

(not especially, see, so I don't think I'm a girl)

|

|

8

|

C1:

|

un-

(yeah)

|

|

9

|

G:

|

otoko da to omowana(i) ore wa betsu ni

man COP QT think:NEG I TOP in particular

(I don't think I'm a guy, me, not especially)

|

-

This exchange is instigated by C1's statement (line 1) that Gaishi 'basically' (ichiô = lit. 'for the time being,' 'after a fashion') thinks of himself as 'male.' When the interactional particle ne does not evoke a response from Gaishi, C1 continues to press. Gaishi responds with an uprising ore (line 4). The uprising intonation here indicates that Gaishi questions his requirement to answer C1 directly. In his next utterance, Gaishi asserts that he does not think anything, more precisely 'because I think I am me' [ore wa ore dakara tte kangaeru: line 6]. In other words, Gaishi is not concerned because he is as he is—and that is just me.

-

The use of discourse marker dakara in line seven (so, therefore, because) suggests that Gaishi offers the speech act of explanation to support his position.[46] That is, he has explained that he is who he is and that is why thinking whether he is a man or not is of no concern to him. When pressed to explain further, Gaishi frames his utterance with the phrase betsu ni ([not] in particular) which emphasises his claim that the issue is of no great concern to him (line 7) Here Gaishi specifically stresses that he considers himself as neither a girl [onna no ko] nor as a man [otoko] and dakara indicates a certain level of irritation at having to repeat himself.[47]

-

Gaishi again employs ore in self-reference in line 9. In a passage he expresses his own ambivalence to gender dichotomies, Gaishi self-refers with a gender indexed pronoun yet emphasises an identity that is not girl-like and not male. It is precisely this identification with 'not-girl' 'not-male' which is of import. The significance of the former is further emphasised when Gaishi is prompted by C1 to elaborate on why he reacts negatively to being labeled as a 'girl'.

(4) sore wa dakara, shinri men de onna ja nai jan betsu ni

(Location: Gaishi's Room, Interlocutors: Gaishi, C1, Topic: Gender)

|

1

|

C1:

|

un:, onna no ko da yo ne, tte iwareta ya da yo [ne]

uhm, girl COP FP FP, QT be told revolting COP FP FP

(yeah, you're a girl aren't you, you wouldn't like being called that would you)

|

|

2

|

G:

|

[un, sore wa ][ ne]

uhm, that TOP FP

(yeah, that's right)

|

|

3

|

C1:

|

[un]

uhm

(yeah)

|

|

4

|

G:

|

yappari imeji ga aru jan, jibun no atama no naka de, onna no ko tte iu no wa,

expectedly image SUB exist right, self LK head LK inside LOC,

girl QT NOM

(of course I have an image, in my head, what girls are)

|

|

5

|

C1:

|

un-

uhm

(yeah)

|

|

6

|

G:

|

nanka sono sa, (1) (ka) yowakute? mitai na no ga aru kara sa nanka,

like, that FP, weak?, like COP NOM SUB exist so FP like

(like, you know, weak? so something like that, like you know)

|

|

7

|

C1:

|

un, (a) so iu fû ni mirareru no wa iya na n da,

uhm, that kind of in looked at NOM TOP yuk COP NOM COP

(yeah, so you don't like being looked at like that)

|

|

8

|

G:

|

un

uhm

(yeah)

|

|

9

|

C1:

|

(a) dôshite?

why

(why?)

|

|

10

|

G:

|

(3) ee tte doshite, sore wa dakara, shinrimen de onna ja nai jan betsu ni

huh QT why, that TOP because, psychological side on woman COP Neg

like particularly

(what, why, that's because, I'm not a woman in the psychological sense, in particular

|

-

In his explanation as to why he dislikes being called a 'girl' Gaishi invokes the social image of girls (line 4). With the adverb yappari Gaishi both appeals to joint social knowledge of what 'girls' are like (he gives an example in the following utterance kayowai [weak]: line 6) and transmits his strong emotional investment in remaining outside of that image. Pressured once again by C1 (dôshite: line 9) to explain just why he doesn't like being seen as 'weak' [kayowai] Gaishi expresses direct surprise (ee tte dôshite [what, why?]: line 10). After a relatively long pause he states that on the psychological side [shinrimen] he isn't a girl (line 10). (Note again the use of dakara signaling irritation and betsu ni which frames the whole utterance as being 'no big deal').

-

As is clear from the above analysis, classifying the use of ore in Gaishi's speech as a mimicry of stereotypical male speech does nothing more than reinforce the misleading concept of a static essentialist gender manifested in gendered speech patterns. It is interesting to note that Gaishi's ore occurs mainly in contexts where his speech partner is a girlfriend or where the topic is that of his own gender identity. In these contexts, Gaishi imputes the masculine and overtly rejects the feminine. In doing so, Gaishi is able to establish a gender binary in which he places himself as the male partner of a male/female duo. In contrast, in contexts where Gaishi is discussing actual sexual experiences he uses gender neutral referent jibun.[48] Aware of the physicality of his birth gender, Gaishi here avoids self reference, which would overtly draw this physicality into focus. On discussions of his own body, Gaishi opts for usage of a more neutral term—one that signifies his own empathy with his subject position and does not reinforce gender performance in the same way as the more overtly 'masculine' indexical ore.

In Conclusion

-

In the above discussion I have discussed the importance of contextual analysis of gender indexical and the shifting meanings of gender as indexed in context. In the analysis of Kazuki's usage of the interactional particle no I identified the problems of tabulating gender indexes without referring to the context in which they are uttered. As Okamoto and others have stressed, a one-to-one relationship of gender to speech is clearly inadequate here. The contextual nature of indexicals necessitates that they be studied in context, that is not as isolated units, but as contextualised components of discourse.[49] While previous studies may illustrate overall patterns of gendered speech, many studies of Japanese gender indexicals have been limited by essentialist notions of 'male' and 'female' which have isolated indexes from their all important contexts.

-

As is evident from my discussion of Gaishi's interactions with a customer above (see excerpt (3)), glossing Gaishi's use of ore as evidence of his claim to some elusive manhood ignores the fundamental contextual functioning of indexes. Gaishi himself makes it clear that rather than categorise himself as a man, he establishes that he is not a girl/woman. While it is safe to assume that pronouns such as ore index gender at some level, the meaning of the gender indexed is clearly not static over all contexts. The masculinity indexed by an onabe's use of ore is not necessarily identical in social meaning to that indexed by a heterosexual man.

-

Recent research of conversational data has identified discrepancies between 'traditional' classifications and natural speech, and called for revisions which acknowledge the importance of wider social factors such as age, intimacy etc.[50] Needless to say, a classification which correlates linguistic forms with 'sex' is inherently problematic. Furthermore as Abe notes,[51] the perception of a specific form as 'feminine' or 'masculine' may be entirely subjective, for, as I propose here, the meaning of gender and how it is perceived is not static. Issues such as sexuality, gender identification, ability and age must be taken into account along with contextual factors such as the relationship between interlocutors, place, topic and so-on.

-

In conclusion let me return to Silverstein's notion of imputed indexicality. As Silverstein states '[a] speaker can create a social persona for himself [sic], playing upon the hearer's perspective of imputed indexicality, where the speaker has characteristics attributed to him [sic] on the basis of the rules for certain utterance fractions.'[52] In his conversations with Sampei, Kazuki does not appeal to Sampei's sense of Kazuki's gender, but to his position as group member, and as his workplace superior. Kazuki effectively implicates Sampei into the Club Marilyn group of hosts by indicating what expectations are made on its members (clothing, dealings with customers.) What is implied and imputed is a position of joint group belonging. Similarly, Gaishi's use of ore does not index his sex or gender in any restrictive essential way, but is part of a repetitive gender performativity which enables him be 'not girl/woman.'

-

Just as the utterance of performative sentences containing performative verbs, such as 'I promise,' effectively produce the state of the verb and constitute 'the doing of an action,'[53] so too are indexes effective in enacting contextual gender. Like performative verbs, elements of language that index gender do not exist in a social vacuum—they are subject to social regulations. Employing the concepts of indexicality and performativity enables us to clearly see how gender in language use can, on the one hand, be untangled from the matrix of heteronormative discourse and, on the other, how the dominant discourse of binary gender and compulsory heterosexism impacts on everyday speech acts. Far from being illustrative of 'deviant' language use, the language of Shinjuku Boys illustrates the importance of context to the interpretation of interactive gender indexing and the changing meanings that gender indexing enacts. It shows the way in which all Japanese speakers negotiate gender, sexuality and identity.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Transcription Notes and Conventions

|

K:

|

Kazuki

|

|

G:

|

Gaishi

|

|

T:

|

Tatsu

|

|

S:

|

New Host Sampei

|

|

C1:

|

Customer 1

|

|

I:

|

Interviewer

|

|

[

|

Simultaneous utterances

|

|

( )

|

Length in seconds of pause

|

|

:

|

Elongated

|

|

?

|

Rising intonation

|

|

!

|

Strengthening

|

|

,

|

Brief pause (usually indicative of one intonational phrase)

|

|

{}

|

Basic non-linguistic actions

|

|

[xx]

|

Undiscernible utterance

|

Appendix 2: Symbols used in gloss

|

AUX:

|

auxiliary verb

|

|

NOM:

|

nominaliser

|

|

COP:

|

form of copula be

|

|

OBJ:

|

object marker

|

|

FP:

|

final particle (interactional/sentence-final particle)

|

|

QT:

|

quotative marker

|

|

LK:

|

linking nominal

|

|

SUB:

|

subject marker

|

|

NEG:

|

negative

|

|

TOP:

|

topic marker

|

Endnotes

[1] This paper is a revised version of Claire Maree, 'Jendâ no Shihyô to Jendâ no Imisei no Henka: Eiga Shinjuku Boys ni okeru onabe no Baai ('Gender Indexicality and the Shifting Meanings of Gender—The Case of an onabe in the Documentary Film Shinjuku Boys'),' in Gendai Shisô 25, 13 (1997): 263-78; Claire Maree, 'Gender, Sexuality and Identity: Performativity and Indexing in the Language of Shinjuku Boys,' paper presented at Lavender Language VI, American University, 1998.

[2] Kim Longinotto, Jano Williams, Shinjuku Boys, Twentieth Century Vixien (Uplink Tokyo) 1995, 16mm, 54min.

[3] For example see Daniel Long, 'Miscellany,' American Speech, 71, 2 (1996) 215-24; Mark McLelland, Male Homosexuality in Modern Japan: Cultural Myths and Social Realities , Richmond: Curzon Press, 2000, p. 8; James Valentine, 'Pots and Pans: Identification of Queer Japanese in Terms of Discrimination,' in Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality , ed. Anna Livia, Kira Hall, London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 95-114.

[4] It is interesting to note that Robertson (Jennifer Robertson, Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan , Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998) briefly refers to the host club New Marilyn in her groundbreaking work on sexual politics in Japan and that famous cross-dressing Japanese troupe Takarazuka. Robertson, however, mistakenly refers to Kabukich˘ (the area in which New Marilyn is located) as being 'Tokyo's infamous gay district' (Jennifer Robertson, Takarazuka , p. 144). Kabukichô is in fact more popularly known as one of Tokyo's infamous entertainment districts, the 'infamous gay district' is a few blocks away in Shinjuku ni-chôme.

[5] In Shinjuku Boys, Tatsu appears in scenes with his long-term (female) partner, and Kazuki talks extensively on screen with his male to female (MTF) transgender partner.

[6] 'Heterogender confronts the equation of heterosexuality with the natural and of gender with the cultural, and suggests that both are socially constructed, open to other configuration (not only opposites and binary), and open to change,' see Chrys Ingraham, 'The Heterosexual Imaginary: Feminist Sociology and Theories of Gender,' in Queer Theory/Sociology, ed. Steven Seidman, Oxford: Blackwell, 1996, p. 169.

[7] A footnote in Coates (Jennifer Coates, Women Talk, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996, pp. 298-99) provides the term 'audist' for the practice which favours spoken language in linguistic analysis. In this paper 'interlocutor' refers to participants in a language exchange.

[8] Sumio Kondô, 'Onna-no-ko to "onna-kotoba"-"Onna-kotoba" wa horobiru no ka' [Girls and "women's language" - Will "women's language" die out?], in Gengo Seikatsu [Language Life] 387 (1984), p. 53.

[9] Anna Livia, Kira Hall, '"It's a girl" Bringing Performativity Back to Linguistics,' in Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality, ed. Anna Livia, Kira Hall, London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 3-18.

[10] Janet S. Shibamoto, Japanese Women's Language, Orlando: Academic Press, 1985, pp. 2-3.

[11]See for example: Hideko Abe, 'The Speech of Urban Professional Japanese Women,' Ph.D. thesis, Arizona State University, 1993; Shigeko Okamoto, '"Tasteless" Japanese: Less "feminine" Speech Among Young Japanese Women,' in Gender Articulated, ed. Kira Hall, Mary Bucholtz, New York: Routledge, 1995, pp. 297-325.

[12] Miyako Inoue, 'Gender and Linguistic Modernization: Historicizing Japanese Women's Language,' in Cultural Performances: Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Women and Language Conference, ed. Mary Bucholtz, A. C. Liang, Laurel A. Sutton and Caitlin Hines, Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group, 1994, pp. 322-33; Orie Endo, Onna-kotoba no Bunka-shi [A Cultural History of Women's Language], Tokyo: Gakuyô-shobo, 1997.

[13] Dorinne E. Kondoh, Crafting Selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

[14] Shigeko Okamoto, '"Gendered" Speech Styles and Social Identity,' in Cultural Performances: Procedeedings of the Third Berkeley Women and Language Conference, ed. Mary Bucholtz, A.C. Liang, Laurel A. Sutton, Caitlin Hines, Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group, 1994, p. 578.

[15] For example see: Shigeko Okamoto, '"Tasteless" Japanese,"; Gendai Nihongo Kenkyûkai, ed., Onna no Kotoba: Shokuba-hen [Women's Language: The Workplace Edition], Tokyo: Hitsuji- shobo, 1997.

[16] For example see: Wim Lunsing, Claire Maree 'Shifting Speakers—strategies of gender, sexuality and language,' in Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People (working title), ed. Janet (Shibamoto) Smith, Shigeko Okamoto, Oxford: Oxford University Press (forthcoming); Naoko Ogawa, Janet Smith (Shibamoto), 'The gendering of the gay male class in Japan: A case study based on Rasen no Sobyô,' in Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality, ed., Anna Livia, Kira Hall, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 402-15.

[17] Butler, Judith, Bodies That Matter: On The Discursive Limits of Sex, New York: Routledge, 1993.

[18] Alessandro Duranti, Charles Goodwin (eds), Rethinking Context: Language as an interactive phenomenon, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 335.

[19] Michael Silverstein, 'Shifters, Linguistic Categories, and Cultural Description,' in Meaning in Anthropology, ed. Keith H. Basso, Henry A. Selby, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1976, pp. 11-55.

[20] A vast body of literature discussing pronouns and sentence-final particles exists in both English and Japanese. To enable easy access to material in English, I use the following texts as references here: Seiichi Makino, Michio Tsutsui, A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar, Tokyo: The Japan Times, 1986; Senko Maynard, An Introduction to Japanese Grammar and Communication Strategies, Tokyo: The Japan Times, 1990; Yasuko Obana, Understanding Japanese: A Handbook for Learners and Teachers, Tokyo: Kuroshio, 2000.

[21] See Elinor Ochs, 'Indexing Gender,' pp. 335-58; Sachiko Ide, 'Sekai no Joseigo, Nihon no Joseigo - Joseigo Kenkyû no Shintenkai wo Motomete [World women's language, Japanese women's language: In search of new developments in women's language research],' in Nihongogaku 12, 6 (1993): 4-12; Naomi Hanaoka McGloin, 'Shûjoshi (Sentence final particles),' in Nihongogaku 12, 6 (1993): 120-24.

[22] The contemporary pronoun system is relatively new to the Japanese language. Obana, offers this brief explanation: 'Thus, personal pronouns in old Japanese did not directly or exclusively refer to first and second persons, or precisely speaking, the status of personal pronouns has not been clearly established in the Japanese parts of speech. Only recently do personal pronouns obtain their own status in grammar although they carry many constraints on their occurrence (se details in Chapter 4). On the other hand, the English 'I' has always designated 'self' (Old English 'ic', Middle English 'ic/ich'), and has never referred to or been referred to by other personal pronouns,' see Obana, Understanding Japanese, p. 190.

[23] Adapted from Seiichi Makino, Michio Tsutsui, A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar, p. 28. This dictionary does not list any 'very formal' second persons. See also Senko Maynard, An Introduction to Japanese Grammar and Communication Strategies, p. 45.

[24] Makino and Tsutsui, A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar, p. 45.

[25] Obana, Understanding Japanese, p. 260.

[26] Makino and Tsutui, A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar, p. 45.

[27] Adapted from Maynard, An Introduction to Japanese Grammar and Communication Strategies, pp. 125-26.

[28] Ochs, 'Indexing Gender,' pp. 340-41.

[29] Ide, 'Sekai no Joseigo, Nihon no Joseigo [World women's language, Japanese women's language],' p. 11.

[30] Ochs, 'Indexing Gender,' p. 340.

[31] So-called onabe bars have been a traditional working place for onabe-identified individuals in the post-war period.

[32] Adapted from Abe, The Speech of Urban Professional Women, p. 170.

[33] Abe, The Speech of Urban Professional Women, pp. 172-73.

[34] In Abe's classification (based on previous studies in this field), 'no + yo', 'no' and 'no yo' are classified as feminine forms expressing mild assertion. 'No ne' and 'no yo ne' as feminine forms expressing questions/criticism. Please note that the interrogative 'direct style + no' is classified as neutral and therefore falls outside present concerns.

[35] Abe, The Speech of Urban Professional Women, p. 169.

[36] McGloin, 'Shûjoshi (Sentence-final Particles),' pp. 122-23.

[37] Kazuki also uses no ne, in his conversation with his partner Kumi.

[38] Sampei appears three times in the remainder of the film and there is a notable difference in his dress style as he adjusts more and more to the club's dress code.

[39] Note that Kazuki uses the form abunee, a coarser form of the adjective abunai [dangerous, risky].

[40] Haruko Minegishi Cook, 'An Indexical Account of the Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No,' in Discourse Processes 13, (1990): 401-39.

[41] Cook, 'An Indexical Account of the Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No,' p. 410.

[42] Cook, 'An Indexical Account of the Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No,' p. 422.

[43] Silverstein, 'Shifters, Linguistic Categories and Cultural Description,' p. 34 as quoted in Cook, 'An Indexical Account of the Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No,' p. 421.

[44] Cook, 'An Indexical Account of the Japanese Sentence-Final Particle,' p. 421.

[45] Fumi Kanemaru, 'Ninshô, Daimeishi, Koshô,' in Nihongogaku 12, 6 (1993): 109-19.

[46] Senko K. Maynard, Discourse Modality: Subjectivity, Emotion and Voice in the Japanese Language, Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1993, p. 55.

[47] Maynard, Discourse Modality, p. 97.

[48] Classification of jibun as a gender neutral self referent is one that could be contested. However, in the current discussion it has been construed as such because there are no overt prescriptive restrictions on the use of jibun according to gender (or sex).

[49] Abe, 'The Speech of Urban Professional Japanese Women.'

[50] Abe, 'The Speech of Urban Professional Japanese Women'; Hirofumi Asada, 'Dai-ni Gengo Toshite no Nihongo no Otoko Kotoba, Onna Kotoba [Women's language and men's language in Japanese-as-a-second language],' in Nihongokyôiku 96 (1998): 25-26. Okamoto, '"Tasteless" Japanese'; Uchida, Nobuko, Kaiwa kôdo ni Mirareru Seisa [Gender in Conversational Activity],' in Nihongogaku 12, 6 (1993) 156-68.

[51] Abe, 'The Speech of Urban Professional Women.'

[52] Silverstein, 'Shifters, Linguistic Categories, and Descriptions,' p. 47.

[53] J.L. Austin, How to do Things with Words, Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1962, p. 5.

|