-

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes distinguishes between two kinds of 'subjects' that any photograph must have: its studium and its punctum.[1]

The studium is what the photograph is, as it were, officially, about.

In a photograph of a fire engine, the fire engine is the studium.

But the second subject is supposedly more elusive: the punctum is more on the viewer's side of things.

It is whatever strikes us first; perhaps an insignificant detail that has crept into the photograph by accident.

A gloved hand here.

An anklet there.

A strange looking collar.

A clock on a mantelpiece.

A shoe.

The punctum is just that, a point that projects out at us as we look.

-

Alastair McNaughton – 'Mac' – is a well-known Australian photographer who writes with his camera.

In my life, he is a kind of punctum in his own right.

As an analyst, I search in vain for the studium.

Apart from winning the Leica and Nikon/Panorama prizes in 1996, his renowned work with the Maasai in Tanzania, and his multiple exhibitions around the world, he's the kind of person who forces a visual illiterate like me to respond to photography.

Or else!

-

Couple of years ago, he told me: 'Once you understand someone's humour and can relate to them, they accept you and tend to forget that you're pointing a camera lens at them.'

That, I think, is part of the secret.

-

I have many of Mac's photographs.

They hang on the walls of my house and my office.

Somewhere there are even the wedding photographs Mac stopped and stooped to take one Spring day many years ago.

Whenever I look at any of his work, I see my punctum right away.

Like Mac, the studium is always more elusive.

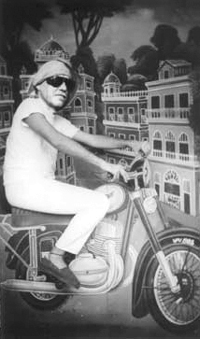

Figure 1. Woman on motorbike, unknown photographer's studio, Cox's Bazaar, Bangladesh.

Figure 1. Woman on motorbike, unknown photographer's studio, Cox's Bazaar, Bangladesh.

|

This is why I simply had to mention the Coke bottle tucked away near the bottom right in the photo of the veiled woman on her cardboard motorbike.

In a photograph composed of so many layers (the sky, the Taj Mahal, the cypress-lined path, the drapes, the central figure, the floor, the studio lights...), that for me is the tiny layer of its own that somehow does not quite fold into the shot.

It's a point that points to itself and says not so much 'Drink Me' as 'See Me'.

Then why – and this is always my problem with Mac's pictures – do I have a harder time finding the studium itself?

This is what I think intrigues everyone who sees his pictures.

For example, in a shot of a shaven and robed monk with a kitten jumping through his hands, kitten in mid-air as though levitated, what I think the shot is all about is the remarkable shadow of the whole 'event'.

|

Mac, with his near-literal mono-vision (always black and white, always with his 'bad eye' closed to the scene, like a hippie Nelson of a photographer), sees depths in planes and colours in shades of grey.

What he photographs is the shadows we always overlook when straining to see what casts them.

-

So when I look again at the woman on the bike in Cox's Bazaar, I know that she is being photographed by the unknown photographer and that Mac is there somewhere photographing that photographic scene.

After all, was this not the conceit of our whole project?

To use photographs to capture the work of photography in 'other' cultural settings outside our comfortable and mutually familiar Euro-Australian picture-scape?

But the woman herself appears, in Mac's picture, the way a patch of black might in a Mondrian.

All of her, that is, except the eyes and forehead.

She opens herself to photography at the same time that she resists its gaze – looking out from the veil, the eternal enigma for the man who wants to take images.

-

So who is this 'man who wants to take images'?

It's a question that links Mac to the photographers he photographs.

Men photograph and women: but we see no (pictures of) women photographers.

The masculine and colonialist will to picture is, itself, on display here.

As someone once said, Mac's photos 'seem to be of people who are like him but also not.'

He captures Indian and Bangladeshi men in the act of capturing whoever happens to pass by.

Then we have to wonder where both gender difference and colonialism actually reside.

If photography once merely affirmed the gap between East and West in classic orientalist fashion, Mac's photos of Indian and Bangladeshi photographers do double duty.

They seem to repeat that orientalist 'desiring' and 'wondering' about the other and also, at the same time, to deeply question it.

For theorists of the image, with a practised eye used to finding instances of 'orientalism' and 'the male gaze', Mac often confounds us with a third visual space of his own.

Sometimes, we don't know where we are.

Irony?

-

So what I see here – in the first picture – is something akin to the black shroud that the photographer himself may use when composing his shot or else when developing it

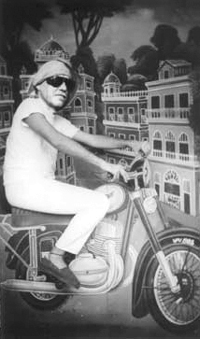

Figure 2. Kishan, a street photographer in Pushkar, Rajahstan, NW India.

Figure 2. Kishan, a street photographer in Pushkar, Rajahstan, NW India.

|

Figure 3. Unknown Hindu photographer, Jaipur, Rajahstan, NW India.

Figure 3. Unknown Hindu photographer, Jaipur, Rajahstan, NW India.

|

The photographer, veiled, shrouded, hides himself away in order to make something else forever visible.

But in this picture, the veiled woman mirrors him back at himself: making herself hidden, except for her own return viewfinder.

The very gendering of photography is, then, partially captured in the shot.

Malek Alloula, in The Colonial Harem, notices as much and more in her reflections on a collection of 'sub-erotic' photo-postcards of Algerian women.

She over-states what must nevertheless be suspected:

These veiled women are not only an embarrassing enigma to the photographer but an outright attack upon him. It must be believed that the feminine gaze that filters through the veil is a gaze of a particular kind: concentrated by the tiny orifice for the eye, this womanly gaze is a little like the eye of a camera, like the photographic lens that takes aim at everything. The photographer makes no mistake about it: he knows this gaze well; it resembles his own when it is extended by the dark chamber or the viewfinder. Thrust in the presence of a veiled woman, the photographer feels photographed; having himself become an object-to-be-seen, he loses initiative: he is dispossessed of his own gaze.[2]

-

This is one reason why the studium is so hard to pin down.

We ask ourselves: what is this a photograph of?

And we draw a blank.

The studium is missing or elusive because it might be the 'unknown photographer' himself.

Or else, the studium might be the studio itself; this scene in a chamber where another chamber (the camera) looks upon another (for Alloula, the veiled woman) looking back at her others.

The studium is, if anything, the primal scene of photography: man looking at woman, woman looking at man, looking at woman looking back....

-

So, with these pictures, we are always caught in an enigma of variations.

Mac's Nikon is an enigma machine and we, as decoders, are often stumped.

In the shot ostensibly 'of' Kishan (Figure 2), do we see Kishan, or else his camera, or else the palace scene in his backdrop?

Once more, we don't quite know where to look.

So perhaps we settle on the draped bench in the 'between', the middle ground.

Or else we may go punctum hunting and settle on his thonged shoe or the ornamented plastic bottletop that he uses as a lens-cap.

-

Moving on to the 'Kishan' picture, it would be easy to fall into the trap of saying: well, now we see a man taking a man's picture, so everything is different.

Just as simple to start with: now the Western professional with his expensive Nikon pictures the Indian street photographer with his homemade box.

Sure, the colonialist story is there – and perhaps even more so in some of Mac's famously beautiful pictures of Wongi children in bush settings.

But that story can never be the studium of these pictures.

Instead, our focus is never allowed to relax.

It shifts and flickers between planes; the aforementioned mono-vision tempting binocular viewers to flip and flop between the backdrop as three- and/or two-dimensional, or to switch horizontally between Kishan and his camera, his right hand claiming ownership but also stroking.

Economy and love in one frame.

Kishan looking through the lenses of his glasses is not, after all, so far away from the woman looking back through Alloula's 'tiny orifice for the eye'.

When I look, I want to entitle the photograph 'Pride' – but pride transformed from sin into virtue.

-

Some months ago, Mac wanted to be in touch from his home in Sydney.

He sent me a letter on the back of a folded pre-print of a photo he was working on.

I suspect it was, for him, just a piece of paper he happened to have in his darkroom at the time.

I wasn't supposed to look at the photo, just read the letter.

Now it's on my wall, folds and all.

The subject appears simple at first: it's the front wall of Mac's favourite Sydney haunt, the Palisade Hotel.

But in the picture, the central window comes alive.

It reflects back the Harbour Bridge, as well as both the shadow and the reflection of an outside hanging globe.

I mention this only because, again, we don't know quite where to look: at the wall (with its usual pub signs), into the hotel itself (as any voyeur might through any window, any lens, any veil, any possibility of the forbidden), or else back out again, behind the photo itself to the Bridge that comes to be framed like a picture in its own right.

Wherever we look, in any of Mac's pictures, there are always sub-pictures – beckoning us towards a completely different meaning.

Punctum and studium refuse to be differentiated.

-

This is why it's just so difficult to wrap it all up into binary differentialist themes like 'race', 'gender', 'colonialialism' and the rest, tempting as this may be.

As soon as we 'see' such things (perhaps, as scholars, over-skilled in interpretation?), they move away and something else, something planar and compositional, asks to take their place.

So used to looking, we suddenly don't know where to look any more.

-

After we drafted our photo-essay, I asked Mac if he was going back to India.

We were sharing a beer and sitting around in his shed.

Of course he was going back!

Then could he, I asked, find out some more about street photography?

He left the next day and shortly sent me back cassette tape of Uday Mitbalkar (a studio photographer) and Yaduendra Sahai (a photographic archivist) speaking about the history of Indian photography.[3]

They spoke fascinatingly and in detail about many aspects of photographic processes and practices, but could offer little historical information about the unique positive-negative paper process (the fatha fath) used by the street photographers, the 'Minto Men'.

-

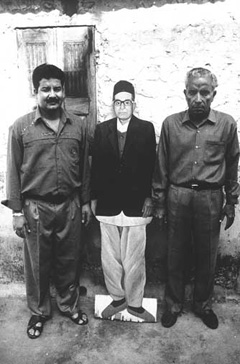

Mac also sent a photo of three generations of street photographers all aligned in one shot.

The father and the son stood either side of the grandfather.

But the grandfather looked younger than the father.

Then I noticed that this central figure – the one who first established the business – was in fact a photograph of that long-dead man, blown up to life size and mounted on cardboard!

And I then began to glimpse the theme of Mac's whole oeuvre.

He was looking out for chances to photograph others who could ask us to shift between a simple 2D plane and the (im)possibility of depth.

He was struggling to show what he could see with this unique mono-chrome mono-vision of his.

Figure 4. Three generations of street photographers, Jaipur, India.

Figure 4. Three generations of street photographers, Jaipur, India.

|

To show what one can see: that was the key to it all, the photographer's stone.

So now I see something else when I look at, for example, showing Zainal Abedin in his studio with his Kodak girl.

Half of me wants to go down the easy route: to read this as M/F, with the plinth acting as the '/' and run on from there: real man, imaginary woman; east and west; clothes vs. flesh, and the rest.

A veritable repeat of Déjeuner sur l'herbe woven in with all the tropes of orientalism?

But this is soon exhausted.

Before long, the theme is the capturing of the sheer fact that photography has always been the art and science of illusion.

The Kodak girl is – like the grandfather – a photograph in a photograph of a photographer's photographic scene.

Her impossibility speaks for the miracle and impossibility of all photographs.

|

My punctum is the bend in her cardboard legs.

(Just like Mac's faulty eye is a punctum – an error that brings us closer to the truth.)

I look at this and I see the very idea of illusion: of what is bought and sold in every photograph.

And more so than in television and film which move too quickly for us to stop and look.

And this is why I can look at a shot like this for hours.

I'm seeing the art – artifice – of photography, at least partially, shown inside a photograph itself.

-

The Left has always celebrated Brecht and Godard, in theatre and film respectively.

Rightly so: they thought they could show the realities behind the thin veil of capitalism.

But what the Left forgot was that the alienation technique also showed the illusory nature of such an exposure itself.

-

For me – and Mac will (I'm sure and I hope) disagree – his work does the same and more for photography.

And it does so prior to and outside any techno-scepticism we may have about Photoshop-type fakery.

He dares to confront the political binaries that can be so easily preyed on today by talk of 'identity politics' (and such like).

And, in all of this, he asks us, through the pictures themselves, who and what we might become when we engage in the terribly simple (and simply terrible) act of looking.

Read in conjunction with:

Street and Studio: Popular Commercial Photography in India and Bangladesh

Endnotes

This paper was originally published in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, with the assistance of Murdoch University.

This page has been optimised for 800x600

and is best viewed in either Netscape 2

or above, or Explorer 2 or above.

|

From February 2008, this paper has been republished in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific from the following URL:

intersections.anu.edu.au/issue8/mchoul2.html.

HTML last modified: 18 March 2008 1039 by Carolyn Brewer.

© Copyright

|

|