-

Since the mid-nineteenth century, there has been an enduring relationship between Western imaginings and the Japanese woman. Dressed in kimono and made up as a geisha, she has often been used in illustrations and cartoons as an archetypical gendered symbol of her country, often to the exclusion of all other symbols. Even when writing on the modernisation of Japan in 1899, as P.L. Pham notes, J. Stafford Ransome 'found space amongst pictures of shipyards and engineering buildings to include pictures of Japanese women posing in kimonos.'[2] In more general descriptions of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as those by Basil Hall Chamberlain, Douglas Sladen, Robert Grant Webster and W. Petrie Watson, the 'state of Japanese womanhood'[3] or, more accurately, how the Japanese man was seen to respond to and treat Japanese womanhood, was often used as a metonym for the state of Japanese civilisation. The common estimation was that, rather than the Japanese man, the quintessentially feminine Japanese woman deserved the exceptional kindness and chivalry of the Western man.

-

For over a century now, Western fiction writers have made ample use of this framework based on race and gender assumptions. As Jean-Pierre Lehmann explains, the universally acclaimed qualities of the Japanese female, those of 'charm, grace, beauty and femininity,' combined with Western suspicions of a tolerant, enthusiastic native sexuality (as opposed to outlawed or repressed sexuality at home) to provide:

ample material for the romantically inclined, resulting in numerous literary and musical works, all with suitably exotic titles: A Japanese Marriage, The Geisha, A Flower of Yeddo, The Lady of the Weeping Willow Tree, Mi-ki-ka, Poupée Japonaise, ... Madame Chrysanthème and Madame Butterfly.[4]

-

An extension of the contemporaneous Western fascination with the aesthetics of Japonaiserie (a term coined by Baudelaire in 1861), this exotic Japan romance genre was pioneered by French writer Louis Marie Julien Viaud (1850-1923), otherwise known as Pierre Loti. The genre most commonly employs the notion of the 'journey's hero'—a Western man bearing 'power over land, women, peoples'[5]—who undertakes to explore Japan's 'erotics of epistemology.'[6] Inevitably, however, these explorations cling to and preserve the myth of Western hegemonic dominance over the Orient, making the genre no less a product of orientalist discourse than the more formal writings 'on Japan'. Yet, the concept of exotic female perfection is by no means the only myth about Japanese women constructed and perpetuated by Western fiction.

-

This paper is an historical overview of these Western myths of Japanese women, ranging over nearly one hundred and twenty years of Western fiction since the late nineteenth century. Nearly always represented according to the eurocentric requirements of the time, the Japanese woman had a slow symbolic maturation from an exotic, yet simple, maidenly innocent in the late nineteenth century to a sophisticated, often deviant, femme fatale by the 1990s. The orientalist ideology underpinning this process of characterisation, however, rarely faltered. Indeed, commercial popularity, as well as a distinct lack of author enthusiasm for problematising it, has regrettably ensured that 'the Japanese woman' remains a fetishised symbol in contemporary Western fiction 'on Japan'.

The Innocent

-

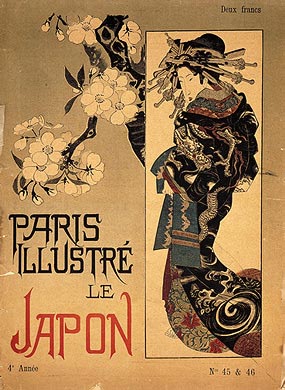

With a strong sense of Western ethnocentrism as a foundation, Pierre Loti's pioneering Madame Chrysanthème (1887), researched on a visit to Nagasaki in 1885, depicted Japanese women very negatively. A misogynist and a racist, Loti made no attempt to hide his distaste for the character of Chrysanthemum: asleep she was 'extremely decorative' but awake, she was 'quite ugly'.[7] Despite this, Loti's novel successfully tapped into the age-old narrative creation of the sexualised 'Eastern woman', famous examples being Cleopatra and Scheherazade,[8] and it had a stunning impact in the Japan-enthused West, including encouraging Lafcadio Hearn, soon to be a prominent Japan scholar and naturalised Japanese, in his decision to leave the United States of America for Japan. There is also a common belief that Loti's novel inspired Vincent Van Gogh to paint a portrait of the imaginary Chrysanthemum. This painting, titled The Courtesan, was actually based, however, on the cover illustration of the May 1886 edition of Paris Illustré, which in turn was a mirror image of a nineteenth century woodblock print by Keisai Eisen.[9]

Figure 1. Van Gogh, The Courtesan

Figure 1. Van Gogh, The Courtesan

|

Figure 2. Paris Illustré

Figure 2. Paris Illustré

|

-

Indeed, Loti's theme of Western man meets Japanese woman has become one of the most enduring narratives throughout the twentieth century in Western fiction 'on Japan'. Imitators soon abounded, including Douglas Sladen's novel A Japanese Marriage (1895) and its sequel Playing the Game: A Story of Japan; a sequel to A Japanese Marriage (1904)[10] and Clive Holland's novel My Japanese Wife (1895), perhaps the first to make a now famous analogy when it described Japanese women as 'butterflies - with hearts'.[11] In the following years also came Sidney James's opera The Geisha (1896), Pietro Mascagni's opera Iris (1898)[12] and John Luther Long's novel Madame Butterfly (1898),[13] inspired by his sister's recollections of her time in Japan with her missionary husband. Long's novel was turned into a hit play by David Belasco in 1900 and was also used as source material by Giacomo Puccini for his opera Madama Butterfly, which premiered in Milan in February 1904. The 'Butterfly' concept continued on in at least eight films made between 1915 and 1995.[14]

-

Australian writer Carlton Dawe's A Bride of Japan (1898) is typical of early works in this Western male/Japanese female romance genre. Heroine Sasa-san, described as having the soul of the goddess Inari looking out her eyes, is betrothed by her parents to a local elderly but rich lord. While a 'true oriental', never dreaming of resisting her parents' decision, she came to associate him with

all that was evil and ugly. His wrinkled face, his bent figure, the lightning glances from his little slits of eyes, were all a source of terror to her ... in less than a month he would hold her to him, and turn his little beady eyes into hers, and breathe upon her and call her his![15]

Luckily for her, however, Sasa-san meets Henry Tresilian who sees her as 'a delicately dainty morsel of orientalism just stepped out of a silk kakemono ... [s]he was a real woman, a daughter of the sun.'[16] Tresilian 'rescues' Sasa-san from her dreadful fate and marries her. It is after the marriage that Tresilian starts to have second thoughts.[17] Carlton Dawe, a devotee of the popular concept that Western blood was weakened by the addition of non-Western blood, wrote that Tresilian saw himself 'as the white man who had sold his birthright'. Previously 'dainty', Sasa-san now becomes 'a piece of tinselled heathenism', possessing 'none of those nice little arts which make the white woman such a dear companion.'[18]

-

Perhaps the single most enduring expression of the genre is James A. Michener's Sayonara: A Novel of Forbidden Love (1954), which was also made into an Oscar award winning film in 1957,

Figure 3. James A. Michener, Sayonara

Figure 3. James A. Michener, Sayonara

|

starring Marlon Brando and Miiko Taka. A story of two romances between, on the one hand, Major Lloyd Gruver and star of the Matsubayashi (based on the Takarazuka) stage Hana-ogi and, on the other hand, Private Joe and Katsumi Kelly, Sayonara describes the tragedy of American servicemen in relationships with Japanese women during the Occupation. As with most works in the exotic Japan romance genre, a comparison of Japanese women with American women is unavoidable. Gruver says of Hana-ogi:

I had come to look upon her as the radiant symbol of all that was best in the Japanese woman: the patient accepter, the tender companion, the rich lover ... they had to do a man's work, they had to bear cruel privations, yet they remained the most feminine women in the world.[19]

|

In contrast, when embarrassed in front of American wives for buying ladies' underwear on Katsumi's behalf, Gruver looks at the faces of his countrywomen:

They were hard and angular. They were the faces of women driven by outside forces. They looked like my successful and unhappy mother ... they were efficient faces, faces well made up, faces showing determination, faces filled with a great unhappiness.[20]

Interestingly, where fifty or so years earlier Western commentators were remarking on the mistreatment of Japanese women by Japanese men, Gruver continues by saying of the American women that 'they were the faces of women whose men had disappointed them.'[21] In the end of Sayonara, Gruver returns to his American girlfriend, leaving Hana-ogi in Japan. The film version, made several years later, ends in the opposite, perhaps signifying a new era of acceptability of miscegenation.

-

While fictional works certainly incorporated an enduring stereotype about Japanese women, it is incorrect to presume that Western perceptions were limited to Madame Butterfly or Sayonara-like images of perfect femininity or, indeed, that Japanese women always figured into fictional works at all. Even as early as the late nineteenth century, the Japanese woman was being portrayed in other ways or, particularly after Japan's success in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, ignored for her male counterparts. Outside the male-dominated romance genre, for example, the Japanese woman retained many of her charms in works by female writers but was often marginalised in comparison with Western women.[22] In Frances Little's The Lady of the Decoration (1906), for example, Little's genteel American lady resident in Japan thinks '[t]he maidens, trotting demurely along in their rainbow kimonas [sic] and little clicking sandals, make a pretty picture,'[23] but she goes beyond Sayonara's hints of 'cruel privations' to suggest a more calculated view of other Japanese women:

[t]hey go plodding past us on the road, dressed as men, mouth open, eyes straining, all intelligence and interest gone.... One day ... one of these women stopped for breath just in front of us. She was pushing a heavy cart and her poor old body was trembling from the strain. Her legs were bare, and her feet were cut by the stones.... With a wistfulness that I have never seen except in the eyes of a dog, she said 'If I paid your God with offering and prayers, do you think he would make my work easier?'[24]

Gentle compassion is, in this case, merely a veil over what remains an acute belief in racial hierarchy, typified by the author's assumption of the superiority of Western civilisation and her classical dehumanisation or animalisation of this Japanese woman.

-

In Constance C. A. Hutchinson's O Hana San: A Girl of Japan (1919),[25] the condition and treatment of Japanese women is also implicit in the author's conviction that the spread of Christianity in Japan would be of great benefit. The character of O Hana-san thinks of the '76,000 girls under the age of 14 in our factories' dying by the thousands from consumption and regrets the 'wicked' fall of her school friend 'good O Miki San who was the very life of our party ... she has sold herself for a paltry debt, and is now a dancing girl in some evil place of amusement.'[26]

-

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the renditions of a feminine metonym for the state of Japanese civilisation generally took second place behind fictional apprehensions of Japan between the Russo-Japanese War and the end of World War II. Works during this time tend to gender Japan almost entirely in the masculine, with virtually no female characters whatsoever.[27] Wartime propaganda in the United States, too, overwhelmingly concentrated on the characterisation of Japanese men, but Frank Capra's 1945 film Know Your Enemy—Japan, for example, did acknowledge the 'miserable plight of rural women, who as adolescents were often contracted out to factories or brothels, and whose assigned role as adults was little more than to perform as "human machines producing rice and soldiers".'[28]

The Innocent to the Worldly

-

It was the liberalism of the post-war period, however, that ushered in a new dimension to the portrayal of Japanese women, moving them away from their literary image of gentle, almost pre-modern innocence. It was perhaps inevitable that the realities of the Allied Occupation—when Western men considerably outnumbered Western women—would combine with historical perceptions of permissive sexual behaviour in Japan to see Japan increasingly portrayed as a delectable paradise for Western men. The exotic Japan novel again rose to prominence in the decades after the war, but this time it was generally of an erotic, rather than romantic, nature.

-

With a salacious focus placed on sex instead of love in such novels, it was also perhaps inevitable that Japanese women, pressed by the genuine hardships of war and the Occupation, would be presented as opportunistic whores. This was, of course, not a new phenomenon. The seventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1830-42) noted primly, presumably of Nagasaki, that 'many of the women live with Europeans and others, receiving the wages of prostitution.'[29] It is not, however, easy to account for the air of disgust, even misogynistic hatred, for Japanese women that resounds in many novels in the post-war period. Such disgust most likely stems from lingering wartime hatred for the Japanese, compounded through victory's reinforced notions of Western supremacy.

From his research into the depiction of women in Western art and literature in the late nineteenth century, Bram Dijkstra's description of the Victorian era's masculine confrontation with the rising prominence of prostitution—that of a 'male's nightmare confrontation with the flower of evil, the woman who wanted money, who did not yield to him in gratitude'—may also be influential. For, despite being apparently liberated from mistreatment by Japanese men, Japanese women were not portrayed in fiction as willing to become companions to Western men out of gratitude, nor because of the undying, self-sacrificial romantic love that had been mythologised in earlier novels. Rather, Japanese women were depicted as perceiving an advantage to be gained by such associations.

-

Many of the illustrations of Japanese women in the novels under consideration in this paper make the women appear far more Western in facial structure than Asian, let alone specifically Japanese. This observation adds some degree of confusion to the issue of the construction of gender identity. With the cover illustration frequently the only visual reference to the Japanese female character, it is interesting to consider the argument of Gina Marchetti who believes that, for a male audience, the tradition of Western women openly masquerading as Japanese female characters in film,[31] promotes 'a fantasy in which a desire for the exoticism of a nonwhite beauty can be rationalized by the fact that the beauty is really Caucasian.'[32]

|

An example of this genre, intended for a Western male audience, is Jerome Denver's Ne-San: A revealing novel of Japan's part time call girls who work by day and love by night (1964). Ne-San involves two Australian men, John Francis and Danny Degan, who are sent by their Hong Kong company to visit Tokyo as a reward for good work. The managing director was 'aware of the temptations, and he strongly advised [them] to succumb to as many as possible.'[33] While investigating 'the charms of the slant-eyed, kimino-clad [sic] beauties who practised an ancient profession with charm and dignity,'[34] the men fall into an abduction racket involving the pro-Communist brainwashing of other American men. Preposterous plot aside, the novel is very interesting for its depiction of Japan and Japanese women.

|

Figure 4. Jerome Denver, Ne-San

Figure 4. Jerome Denver, Ne-San

|

The narrator, John Francis, who has an Australian fiancée, observes:

any woman who lets husband or boy-friend go to Tokyo alone can look at him on his return and wonder. She can remember the story of King David watching a girl take a bath on a rooftop.

He was tempted and he succumbed. That's the measuring stick. Any woman who lets her man go to Tokyo alone ought to be sure that he has greater will-power than King David, otherwise she can be suspicious of his behaviour in Japan. Believe me, it isn't the poor quality of the man, it is the high quality of the temptation.[35]

-

Read in isolation, this short passage seems to be similar in nature to the double-edged praise offered to Japanese women in the exotic romance genre, for example, in Sayonara. However, when read in concert with the plot of the novel and, specifically, Denver's characterisation of Japanese women, the implication of 'high quality' becomes less a commentary on female perfection and more an emphasis on sexual availability, sexual accommodation and simple opportunism. John Francis and Danny Degan spend their time bar-hopping and moving from one girl to the next. Ne-san, of the title of the book, is the first girl Francis picks up in a Ginza bar. Although it turns out that she is a Tokyo University-educated policewoman, working undercover to protect American male tourists from abduction, it is made clear that she can be essentially bought for sex by presents. To cap off the portrayal of her blasé attitude to sex (naturally shared by all women in Japan), she had been introduced to sex for her undercover role by a 'kind and tender' police inspector.[36]

-

It is interesting in retrospect then, that one of Ne-San's other female characters, Penelope Dannock, an Australian girl studying for her doctorate, asks John Francis if he has read any books on Japan, particularly ones on the changing status of women. While Francis thinks to himself that he had read them 'with great satisfaction and interest, for one reason,' Dannock continues and says, with no sense of irony, that there is 'a violent philosophical revolution being enacted in this country [Japan] right now, and all they [Westerners] write about is Japanese strumpets.'[37] The irony, however, comes at the end, when Dannock turns out to be far more opportunist than the Japanese 'strumpets' she abhors, as she is arrested as part of the abduction racket.

-

Dannock's catty characterisation of Japanese women is shared by the main character of another post-war novel of this type, Ronald Kirkbride's Tamiko: A Sensuous Novel of Life and Love in Modern Japan (1959). On visiting the American embassy in Tokyo, Ivan Balin observes that he could:

understand why these Japanese girls married Americans—they were belittled and ill-treated by their own men—but he was at a loss to understand why his ... countrymen should be partners in such a conspiracy. Most of them ... had picked up these ugly round-faced Japanese girls with their gold teeth and greasy bobbed hair in the Ginza bars or outside the PX for a quick lay, and had not been able to break with them. This he also understood, for they were good bed companions.... But they were nothing more than tarts, and ugly ones at that.[38]

Figure 5. Ronald Kirkbride, Tamiko

Figure 5. Ronald Kirkbride, Tamiko

|

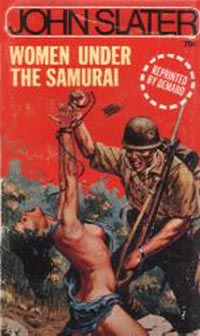

Figure 6. John Slater, Women Under the Samurai

Figure 6. John Slater, Women Under the Samurai

|

Japanese men, by contrast, feature little in the post-war erotic Japan novels such as Ne-San and Tamiko. That is not to say they do not feature at all. John Slater's Women Under the Samurai (1964), for example, is a blatant attempt to cash in on the popularity of World War II stories in the post-war period by drawing upon a common theme of Western wartime propaganda: the sexual mistreatment of Western women by Japanese men.[39] Slater's novel depicts on the cover a Japanese soldier leering at a barely covered white woman suspended from tied wrists. The inside blurb leaves little to the imagination:

The Australians knew that the renegade Japs woud [sic] use every evil torture to make the girls confess. They knew how to get the truth in a crude and brutal way.[40]

The Worldly to the Deviant

-

By the 1970s, novels such as James Clavell's Shogun (1975)[41] caused Sheila Johnson to speculate that the general movement from images of cherry blossoms, tea ceremonies and geisha in the 1950s and 1960s (not inclusive of novels set during World War II, such as fictional memoirs) towards the more masculine imagery of shoguns and ninjas in the 1970s was a 'salutary sign' that the United States was coming to perceive the 'masculine' side of Japan.[42] Yet, even as in the post-war novels that referenced Japanese men during World War II, such as Slater's Women Under the Samurai, the shogun and ninja genre popularised by Clavell was irrevocably tied to Japan's past. It was not until the mid-1980s that Japan's 'masculinity' was consciously linked to the present or near future. Drawing upon a general apprehension created and sustained by Japan's overwhelming economic success in the post-war period, Western fiction saw the rise of a 'Japan' genre of popular fiction, with perennial 'Japan' authors such as Eric Lustbader, Marc Olden and Guy Stanley, as well as best-selling novels by more general authors, such as Tom Clancy, Michael Crichton, Clive Cussler, Jay McInerney and David Morrell.[43]

-

The portrayal of Japanese women in the 'Japan' genre of this period promotes the dualism of female innocence and deviance. In the first instance, markedly in the overly stereotypical novels written as one-offs by popular authors, such as Clancy, Crichton, Cussler, McInerney and Morrell, Japanese women, and indeed frequently all women, are marginalised in the narrative. Japanese women are usually not main characters, play little role in the plot (if any) and are barely fleshed out to two-dimensional status, let alone fully characterised. The portrayal of Japanese women as objects continues unabated from previous fictional incarnations, including the theme that Japanese women continue to be ill-treated by Japanese men.

-

In Jay McInerney's Ransom (1986), for example, the most prominent female character is Akiko Ryder. Her husband, Miles—an American bar and shop owner in Osaka—when obliged to explain his frequent womanising 'invoked the when-in-Rome theory, claiming that Japanese women expected no more fidelity than Japanese men delivered.'[44] Ironically, it seems that Western men can also disappoint Japanese women. Other female characters include Yukiko, a fiery, short-haired, Berkeley-educated, socialist radical who 'worked hard at being unattractive'[45] and who is introduced mostly for comic relief; and Haruko, a worker at a Turkish bathhouse[46] that Chris Ransom reluctantly visits with his karate sensei. Ransom inspects Haruko for 'signs of abuse, bruises, needle tracks, tattoos—anything to confirm his sense of the involuntary nature of her line of work' and feels sorry that 'she had to wash and fuck strange men for a living.'[47] McInerney also underscores the long-standing tradition of Western misconceptions about the role and function of geisha with Ransom's short conversation with a visiting American male tourist in a Kyoto hotel:

- 'Say, what about these geisha?'

- 'What about them?'

- 'Where do you find them?'

- 'About a mile from here in an area called Gion. But that doesn't mean you can find them.'

- ... 'What are they like?'

- 'Expensive.'

- 'Do they ... Are they ... you know?'

- 'Not exactly,' Ransom said. 'You need an introduction just to get your foot in the door, and lots of money. What you would get for your money is conversation, mild flirtation, singing and dancing.'

- 'No sex?'

- 'You'd have to spend months, and thousands; then, maybe.'

... 'So much for Oriental nookie,' Constable said with a wink. Catching sight of his wife, he put a finger to his lips. 'Mum's the word.'[48]

Figure 7. Michael Crichton, Rising Sun

Figure 7. Michael Crichton, Rising Sun

|

Likewise, amongst the many male characters in Michael Crichton's Rising Sun (1992),[49] the only significant female character is Theresa Asakuma, a beautiful expert in film imaging who aids in the solving of a sex murder mystery. The portrayal of Asakuma, however, is marked by a strong streak of eurocentrism, designed to underline the novel's anti-Japanese theme. When the investigating police officer, Peter Smith, asks Asakuma how she feels, as a Japanese, helping them with the murder case, it becomes quickly apparent to the reader that her likeability as a character lies in the fact that she is not entirely ethnically Japanese. Rather, as she tells Smith, she is ainoko, a love-child of a Japanese woman and, in this case, a kokujin, a black American. She is also deformed, making her 'lower than burakumin' and 'shameful' to her family and community.[50]

|

These elements of characterisation are designed to gain sympathetic approval from the Western reader and to suggest Japanese intolerance of miscegenation and disability.

-

Ironically, given a history of being portrayed in Western fiction as two-dimensional, passively feminine or sexual objects, the depiction of Japanese women in novels from the 1980s onwards occasionally becomes diametrically opposite, something perhaps hinted at obliquely by Tiger Tanaka in Ian Fleming's You Only Live Twice (1964) when he commented to James Bond that Japan's 'American residents ... enjoy the subservience, which I may say is only superficial, of our women.'[51]

-

Even as Chinese women had became sinister and treacherous in Western novels in the 1920s and 1930s through such characters as Fah Lo Suee, daughter of Sax Rohmer's infamous Fu Manchu,[52] many of the characteristics that Western fiction previously ascribed only to Japanese men became associated with the Japanese woman. While still incredibly appealing for her femininity, this new character of Japanese woman could not only be delightful, she could be devious, deviant and occasionally even deadly. Rather than a blurring of stereotypical gender attributes, however, this was a rise of the active rather than the passive orientalist image of the feminine 'Other'. This new construction fitted the emotional and political positionings of Western authors in the 1980s and 1990s far better than did a passive characterisation in terms of the fears raised by Japan's economic success in that period.

-

Now often a femme fatale-type predator, the Japanese woman's motivation is not the simple opportunism of escape from war-ravaged Japan, as it was in Tamiko (1959) and Ne-San (1964), but rather the gratification of her own desires, including sexual pleasure, revenge and power. It may be attributing too much coherent knowledge of Japanese cultural history to Western authors but this new character of Japanese woman does seem to draw upon the historical mythologisation of women in Japan as cruel or vengeful seductresses of men.[53] Certainly, it does accord, however, with widespread notions in Western art and literature of the late nineteenth century that all women had 'a basic instinct that made them into predators, destroyers, witches—evil sisters.'[54]

-

Yukio, in Eric Lustbader's The Ninja (1980), for example, sees love, like loyalty, as an 'alien concept', and sex is the 'only thing that makes [her] happy.'[55] In the novel, the first time she meets Nicholas Linnear, when he is thirteen and she is fifteen, she asks him to dance and uses the bulk of her kimono to hide the fact that she is rubbing herself against him in front of six hundred partygoers.[56] When they meet again several years later, she surprises Nick in the shower, they have sex and she demands that he hit her in order that she might climax.[57] Later that year, after she masturbates him in a bunraku theatre, he wonders whether she is a nymphomaniac but then asks himself whether it would make any difference to him.[58] Reversing the historical trend, in this case Yukio disappoints Nick, using his love for her to lure him into a deadly trap set by his evil cousin Saigô, her previous lover, who kills her when her usefulness ends.

-

Akiko in Eric Lustbader's The Miko (1984), however, spurns her sexuality, reluctantly engaging in sexual relations only when it is necessary to perpetuate her plans of revenge for the death of her father. The daughter of Yoshiwara oiran courtesan, Akiko spends her whole life struggling to be:

free of woman's traditional role as servant to man. Her rejection of all that her mother had been, her revulsion for that lofty state of tayu [the highest rank of courtesan] had this as its basis. As did her decision to train in the most demanding of the martial arts: man's work. All her life she had fought to take her place beside men as an equal.[59]

However, Akiko's desire to become proficient at 'man's work' sees her become a 'pawn to the drives and hatreds' of men. She kills her enemies using her skills as a miko or ninja sorceress but does not realise the extent to which she is herself manipulated.

-

The blurring of behavioural attributes between feminine and masculine in Japanese women is an even stronger theme in Eric Lustbader's Black Blade (1992).[60] At first, the cliché of feminine aesthetic perfection is very much in evidence. The first woman introduced in the novel, kneeling behind a standing man, kimono-clad, with a tray for the tea ceremony, is viewed approvingly by a Japanese male character for her 'there-not-there attitude rare in these modern times.'[61] Only three pages later, American Lawrence Moravia ties up a beautiful Japanese woman in a bondage game and notes the effect of the red silk cord on her skin, that 'in concert with her smooth, firm flesh created a kind of artwork, a living sculpture that was as aesthetically pleasing as it was sexually arousing.'[62] Another character,Yuji Shian's wife was, 'beautiful, delicate and fragile, a porcelain doll whom he could admire as all his associates admired her. In a way she was another symbol of his burgeoning success.'[63] After his unnamed wife commits suicide, Yuji grows angry and hates her, thinking that 'he had never before been aware that she could be so in control of her life.'[64]

-

The theme of control is a major one in this work. As the novel continues, it becomes apparent that the Japanese female characters, rather than being passively subservient to men, are, in fact, the dominant actors. While operating behind the façade of male leadership, the Toshin Kuro Kosai [the Black Blade Society, which aims to extend its post-war economic leadership of Japan to the rest of the world] is actually run by the 'Reverend Mother'. Far from passive, this unnamed woman, it is rumoured, has long hair so that she might easily strangle her lovers; has a legendary appetite for sex (including with very young boys); and is compared to a fanged demonic entity as she uses her psychic ability to draw power from others.[65] The twist of the novel comes at the end, however, when it is revealed in the final pages that all of the Reverend Mother's evil machinations were for naught. The actual power of the Toshin Kuro Kosai resides, not in the Reverend Mother, but in the character of Evan, who is often used as a passive sexual object by various men throughout the novel and who is quite likely the kneeling 'there-not-there' woman first introduced. Whereas the evil of the Reverend Mother was apparent and open, Evan hides her greater evil behind an accomplished façade. The theme seems to be that voiced by one of the main characters early on in the novel: 'If you trust a woman, you will eventually be disembowelled.'[66]

-

Unlike the Reverend Mother and Evan, who mostly manipulate behind the scenes, however, the main character of Guy Stanley's Reiko (1995),[67] Reiko Takeshita, is out there doing her own dirty work. A fictional member of the Japanese Red Army, famous for their actual terrorist activities in the late 1960s and onwards, Reiko's crimes in Japan allegedly include the killing of two policemen and fourteen of her followers, including her own brother, and the hijacking of a Japan Airlines flight to North Korea.[68] Faking her death in Israel in 1979, she became an assassin:

She had no moral qualms about her work, no conscience to distract her. Reiko was an assassin: she needed to kill ... I believe she has found another outlet for her killing skills, a much more rewarding one, giving her wealth and comfort after years of physical deprivation in the guerrilla camps. After all, Reiko's a woman.[69]

Apparently, at least according to the (perhaps deliberate) sexism of the author, Reiko's gender would influence her towards a life of comfort. Certainly, despite being in her forties, Reiko is still characterised as exceptionally feminine, with her physical beauty, 'tall, long legs, exceptional figure', 'short, full, high buttocks' remarked upon several times.[70] Her life of comfort, however, comes from her work as an assassin. Reiko kills with cold, dispassionate ease. Her victims include a Tokyo City University professor (shot); a Finnish member of the World Health Organisation (shot); a driver for a Diet member (shot); and a park ranger (bludgeoned with a spade). She also attempted to murder a police officer (knife) and a journalist (shot). Repudiating the stereotypical dominant-subordinate relations between Japanese men and women, and almost spoofing the Japanese hostess club scene common to these novels, Reiko is the patron of a host-boy, Tomio Mochizuki, whom she maintains for sex, giving him gifts of money and expensive clothes and occasionally flying him to meet her overseas.[71] She takes the lead in all their sexual encounters and Mochizuki delights in her behaviour, which is so unlike that of the ordinary middle-aged housewife client.

-

By the mid-to-late 1990s, the bursting of Japan's economic 'bubble' and the general downturn in the economic climate gradually saw a reduction in the 'aggressive' Japan genre of Western novels and, consequently, a reduction in these types of depictions of Japanese women. The apparent cyclical return of Western interest in the more gentle exoticised side of Japan is perhaps typified best by Arthur Golden's highly successful, fictionalised story of a Gion geisha in Memoirs of a Geisha (1998), which is scheduled to be filmed by Steven Spielberg for release in 2003. Anne Allison argues persuasively that Memoirs of a Geisha is not, in fact, much of an improvement in the portrayal of Japanese women to the outside world:

I find it disturbing that this is the text, fictional and imaginary, about a behaviour so minor, antiquated, and fetishized in Japan today ... the confusion between the historical authenticity ... and its fantasy story is highly problematic.[72]

-

Also following the trend to look towards the past, Liza Dalby narrativised the voice of Murasaki Shikibu, the eleventh century court lady author of perhaps the world's first novel Tale of Genji [Genji Monogatari] in The Tale of Murasaki (2000).[73] These two novels have overwhelmingly perpetuated the myth of the exotic Japanese woman and it is disturbing, in this post-Saidean era, that rather than coming from commercialised popular fiction writers whom one might duly expect to utilise such fallback stereotypes, both are by authors with strong academic credentials in Japanese studies.[74] Golden and Dalby, in fact, use their status to promote their works.

-

Strangely, it is in works by popular writers of contemporary Western fiction that strong but stable Japanese or Japanese-American female characters, unlike Yukio, Akiko, the Reverend Mother, Evan or Reiko, have begun to appear. Compulsively shy Akiko Ueno in Ruth Ozeki's My Year of Meat (1998), for example, draws strength from watching a female Japanese-American television presenter leave her abusive salaryman husband and move to the United States to have her baby—the product of rape in marriage.[75] There is an accord among critics that it is the characterisation of Rei Shimura, a Japanese-American, Tokyo-based antiques dealer and accidental detective, in Sujata Massey's series of novels[76] that makes them so appealing:

It's the meddling, mixed-up, manipulative Rei Shimura who supplies the real interest. Too bad she's fictional—she's the urban survivor we'd all like as a pal in Tokyo.[77]

-

Tellingly, however, these female characters have been written by women themselves. So far, Western male authors have generally stubbornly clung to the established stereotypes of Japanese women. The best possible example of this is Richard Setlowe's ludicrously premised and stubbornly anachronistic The Sexual Occupation of Japan: A Novel (1999).[78] The novel was plotted on the concept that Japan's drive to succeed economically in the post-war period was based entirely on Japanese males' jealousy of American conquests of Japanese women, charmingly described as Japanese men 'whipping their cocks out on the table to be measured.'[79] As such, the novel draws a large part of its characterisation of Japanese women from the historical figure of Sada Abe. In 1936, this low-class geisha strangled her lover, severed his penis and carried it through the streets in a furoshiki cloth wrapper—a crime repeated by another woman in Nagoya in 1982.[80] The main character of Setlowe's novel, Peter Saxon, (a deliberate selection of name one would assume) decides that 'apparently Madame Butterfly was a Western male fantasy' after hearing from his Japanese girlfriend the fictionalised story of the geisha 'Ono-no' (again a pun, one assumes) who mutilates her lover when he leaves her.[81]

-

That Madame Butterfly was a Western male fantasy given voice by Pierre Loti may well be true but, as Western fiction over the last century has shown, fantasy sells and while it does, authors from Eric Lustbader to Arthur Golden will continue to churn out novels depicting Japanese women as fetishised symbols of Japan. In the future, it can be hoped that authors,as Anne Allison, puts it 'tell better stories that are imaginative and compelling without falling into the trap of exoticising or essentialising.'[82] Or at least, if one must fall into this enticing and well-used literary chasm, to do it with some notable and insightful recognition of the problematic ideological underpinnings of exoticism and the 'other'.

Endnotes

[1] Lafcadio Hearn, Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, New York, Macmillan, 1913 (first published 1904), p. 393. Hearn himself married a Japanese woman.

[2] J. Stafford Ransome, Japan in Transition: A Comparative Study of the Progress, Policy and Methods of the Japanese since their War with China, London: Harper, 1899, cited in P. L. Pham, 'On the Edge of the Orient: English Representations of Japan, circa 1895-1910,' Japanese Studies 19, 2 (September 1999): 163-81, p. 172.

[3] Pham, 'On the Edge of the Orient,' pp. 173-75.

[4] Jean-Pierre Lehmann, The Image of Japan: From Feudal Isolation to World Power, 1850-1905, London: George Allen & Unwin, 1978, pp. 90-91.

[5] Rana Kabbani, Imperial Fictions: Europe's Myths of Orient, London: HarperCollins, 1994, pp. 7-13. For a discussion of orientalism, see Edward W. Said, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, London: Penguin Books, 1978, 1995.

[6] A term used by Anne Allison in her discussion of Arthur Golden's Memoirs of a Geisha, London: Vintage, 1988, see Anne Allison, 'Memoirs of the Orient,' Journal of Japanese Studies 27, 2 (Summer 2001): 381-98, p. 388.

[7] Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysanthème, New York: Current Literature Pub., 1910 (first published 1887), quoted in David Walker, Anxious Nation: Australia and the Rise of Asia 1850-1939, St. Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 1999, p. 136.

[8] See, for example, the discussion in Kabbani, Imperial Fictions, pp. 14-22, 33.

[9] Endymion Wilkinson, Japan Versus the West: Image and Reality, London: Penguin Books, 1991, p. 116. See 'Courtesan News Release', National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 26 September 1998, accessed 1 January 2002.

[10] Douglas Brooke Wheelton Sladen, A Japanese Marriage, London: Black, 1895; Playing the Game: A Story of Japan; a sequel to A Japanese Marriage, London: F. V. White, 1904.

[11] Clive Holland, My Japanese Wife, New York: R. A. Everett, 1903 (first published 1895), p. 92.

[12] Sidney James, The Geisha, 1896; and Pietro Mascagni, Iris, 1898, cited in Wilkinson, Japan Versus The West, pp. 117, 270, note 26. See Mascagni's libretto on the following website:Iris.

[13] John Luther Long, Madame Butterfly: Purple Eyes; A Gentleman of Japan and a Lady, New York: The Century Co., 1898, available online at the University of Virginia's AS@UVA Hypertexts Project, accessed 1 January 2002.

[14] According to the online Internet Movie Database, accessed 1 January 2002, these are Madame Butterfly (1915), (1932) and (1995), Madama Butterfly (1955), Harakiri (1919), Ménage du Madame Butterfly (1920), Il Sogno di Butterfly (1939) and Butterfly (1993). For further interpretations of the Madame Butterfly story, see Maria Degabriele, 'From Madama Butterfly to Miss Saigon: One Hundred Years of Popular Orientalism,' in Critical Arts 10, 2 (1996): 105-18; and Gina Marchetti, 'The Scream of the Butterfly: Madame Butterfly, China Gate, and 'The Lady from Yesterday,' in Romance and the 'Yellow Peril': Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994, pp. 78-108.

[15] Carlton Dawe, A Bride of Japan, London: Hutchinson, 1898, quoted in Robin Gerster (ed.), Hotel Asia: An Anthology of Australian Literary Travelling to the 'East', Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 1995, p. 110.

[16] Quoted in Gerster, Hotel Asia, p. 113.

[17] Quoted in Gerster, Hotel Asia, p. 114.

[18] Quoted in Gerster, Hotel Asia, pp. 114-5, 116-7.

[19] James A. Michener, Sayonara: A Novel of Forbidden Love, London: Corgi Books, 1968 (first published 1954) p. 127. For further discussion of Sayonara, see Gina Marchetti, 'Tragic and Transcendent Love: Sayonara and The Crimson Kimono,' in Romance and the 'Yellow Peril', pp. 125-57.

[20] Michener, Sayonara, p. 120.

[21] Michener, Sayonara, p. 120.

[22] This is also common in Western female writings on Chinese women, see Ouyang Yu, 'The Other Half of the 'Other': The Image of Chinese Women in Australian Fiction,' Australian and New Zealand Studies in Canada 11, (1994), accessed 1 January 2002.

[23] Anon. [Frances Little], The Lady of the Decoration, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1906, p. 32.

[24] Little, The Lady of the Decoration, pp. 136-37.

[25] Constance C. A. Hutchinson, O Hana San: A Girl of Japan, London: Church Missionary Society, 1919.

[26] Hutchinson, O Hana San, p. 126.

[27] See, for example, in the United States: Marsdon Manson, The Yellow Peril in Action: A Possible Chapter in History, San Francisco: Britton and Rey, 1907; Ernest Hugh Fitzpatrick, The Coming Conflict of Nations, or, the Japanese-American War, Springfield: H. W. Rokker, 1909; Peter B. Kyne, The Pride of Palomar, New York: Cosmopolitan, 1921; and Wallace Irwin, Seed of the Sun, New York: Doran, 1921.

[28] John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, New York: Pantheon Books, 1986, pp. 22.

[29] Wilkinson, Japan Versus the West, p. 108.

[30] Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siecle Culture, New York: Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 358.

[31] See, for example, My Geisha (1961), which sees Shirley Maclaine star as a popular Hollywood comedy actress who travels to Japan and secretly takes a part in her director husband's film version of Madame Butterfly and, more recently, the TV series American Geisha (1986) which depicted an American woman learning to be a geisha, modelled on anthropologist Liza Dalby, author of Geisha, London: Vintage, 2000. Dalby is consultant to Steven Spielberg's forthcoming film of Arthur Golden's Memoirs of a Geisha (scheduled release 2003).

[32] Marchetti, Romance and the 'Yellow Peril', p. 177.

[33] Jerome Denver, Ne-San: A revealing novel of Japan's part time call girls who work by day and love by night... , London: Stag Publishing Co, 1964, p. 8.

[34] Denver, Ne-San, p. 9.

[35] Denver, Ne-San, pp. 55-6.

[37] Denver, Ne-San, p. 47.

[38] Ronald Kirkbride, Tamiko: A Sensuous Novel of Life and Love in Modern Japan, London: Pan Books Ltd, 1959, p. 9.

[39] John Slater, Women Under the Samurai, Sydney and Melbourne: Scripts Publication, 1964. See, for example, 'This is the Enemy,' a poster of a Japanese soldier carrying off an unconscious, naked white woman, reprinted in Dower, War Without Mercy, p. 189.

[40] Slater, Women Under the Samurai, p. 3.

[41] James Clavell, Shogun, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1975. For other similar novels see works by Robert Shea, Christopher Nicole and Dov Silverman.

[42] Sheila Johnson, The Japanese Through American Eyes, Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988, pp. viii-ix, 109.

[43] See the discussion on this topic and its links to contemporaneous 'Japan-bashing' in Narrelle Morris, 'Paradigm Paranoia: Images of Japan and the Japanese in American Popular Fiction of the Early 1990s,' Japanese Studies 21, 1 (2001): 45-59.

[44] Jay McInerney, Ransom, London: Fontana Paperbacks, 1986, p. 24.

[45] McInerney, Ransom, pp. 63-6.

[46] An outraged Turkish diplomat in the mid-1980s pointed out to the Japanese press that there was nothing Turkish about Toruko-buro, the so-called Turkish bath. Coming just before the 1985 revisions to the Law on Businesses Affecting Public Morals, the Japan Bath Association selected a new name 'Soapland' for the businesses in a competition, see Nicholas Bornoff, Pink Samurai: An Erotic Exploration of Japanese Society, London: HarperCollins, 1994, p. 398. McInerney's use of 'Turkish Bath' in 1986 probably accurately represents the difficulty in altering such names by decree.

[47] McInerney, Ransom, p. 198-9.

[48] McInerney, Ransom, pp. 91-2.

[49] Michael Crichton, Rising Sun, London: Arrow Books, 1992.

[50] Crichton, Rising Sun, p. 302.

[51] Ian Fleming, You Only Live Twice, London: Coronet Books, 1990 (first published 1964), p. 59.

[52] See, for example, Sax Rohmer, Daughter of Fu Manchu, New York: Doubleday, 1931.

[53] As seen, for example, in Namboku's 'Yotsuya Kaidan' ['The Yotsuya Ghost Story'], a nineteenth century kabuki play; and Tanizaki Jun'ichiro's female characters in Naomi, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1986; The Key, London: Secker and Warburg, 1962; and the Diary of a Mad Old Man, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971. See the discussion in Bornoff, Pink Samurai, pp. 555-60.

[54] Bram Dijkstra, Evil Sisters: The Threat of Female Sexuality and The Cult of Manhood, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996, p. 3.

[55] Eric Van Lustbader, The Ninja, London: Granada, 1980, pp. 367, 370.

[56] Lustbader, The Ninja, p. 156.

[57] Lustbader, The Ninja, pp. 262-66.

[58] Lustbader, The Ninja, pp. 369-71.

[59] Eric Lustbader, The Miko, London: Granada, 1994.

[60] Eric Lustbader, Black Blade, London: Grafton, 1992.

[61] Lustbader, Black Blade, p. 13.

[62] Lustbader, Black Blade, p. 17.

[63] Lustbader, Black Blade, p. 133.

[64] Lustbader, Black Blade, p. 133-34.

[65] Lustbader, Black Blade, pp. 445, 540-42, 592.

[66] Lustbader, Black Blade, p. 133.

[67] Guy Stanley, Reiko, London: Pocket Books, 1995.

[68] Stanley, Reiko, pp. 244-5. Fourteen bodies were discovered by police in the mountains north of Tokyo in February 1969, apparently the result of a fall-out in the ranks of the JRA. The JRA also hijacked JAL flights in the 1970s, though none to North Korea.

[69] Stanley, Reiko, pp. 31, 245.

[70] Stanley, Reiko, pp. 195, 210.

[71] Stanley, Reiko, pp. 339-44.

[72] Allison, 'Memoirs of the Orient,' pp. 397-98.

[73] Liza Dalby, The Tale of Murasaki, London: Chatto & Windus, 2000. See also Dalby's website for the novel The Tale of Murasaki, accessed 1 January 2002.

[74] Arthur Golden holds a B.A. in East Asian art from Harvard College, an M.A. in Japanese history from Columbia University and an M.A. in English from Boston University; Liza Dalby holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from Stanford and is the author of the non-fiction works Geisha, London: Vintage, 2000 (first published 1983); and Kimono: Fashioning Culture, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001 (first published 1993).

[75] Ruth L. Ozeki, My Year of Meat, London: Pan Books, 1999.

[76] Sujata Massey, The Salaryman's Wife, New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1997; Zen Attitude, New York: Harper, 2000; The Flower Master, New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1999; The Floating Girl, New York: Avon Books, 2000; and The Bride's Kimono, New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

[77] Promotional blurb from a review in the Pacific Stars and Stripes, Massey, The Salaryman's Wife, first inside page.

[78] Richard Setlowe, The Sexual Occupation of Japan: A Novel, Sydney: HarperCollins, 1999.

[79] Setlowe, The Sexual Occupation of Japan, p. 25.

[80] Bornoff, Pink Samurai, pp. 568-69. The figure of Sada Abe has also been immortalised in two films: Noboru Tanaka's A Woman Called Sada Abe (Jitsuroku Abe Sada) (1975) and Nagisa Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses (Ai no corrida) (1976), see the online Internet Movie Database, accessed 1 January 2002.

[81] Setlowe, The Sexual Occupation of Japan, pp. 52-3.

[82] Allison, 'Memoirs of the Orient,' p. 398.

|