-

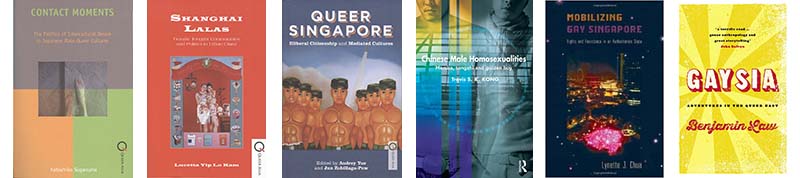

In recent years the idea or notion of a 'queer Asia' as a field of study or inquiry has emerged. However, as it goes with umbrella terms covering vast geographical regions and in this case also a considerably diverse range of sexual and political identities, a bit of wind from the wrong direction flips over what was neatly covered and questions its strength. It is the question of queer Asia in terms of its coverage and usage that is at the heart of this article. I will engage with this by exploring a number of recent publications on queer life in Asia, three of which were published in the Queer Asia series of Hong Kong University Press. In Contact Moments: The Politics of Intercultural Desire in Japanese Male-Queer Cultures Moments, Katsuhiko Suganuma engages with the 'politics of intercultural desire in Japanese male-queer cultures'[1]; Lucetta Yip Lo Kam discusses 'female Tongzhi communities and politics in urban China' in Shanghai Lalas: Female Tongzhi Communities and Politics in Urban China[2]; and in Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, edited by Audrey Yue and Jum Zubillaga-Pow, the notion of 'illiberal citizenship and mediated cultures' is explored in relation to the development of queer life in Singapore.[3] Travis S.K. Kong's exploration of masculinities and sexualities among Chinese gay men in Chinese Male Homosexualities: Memba, Tongzhi and Golden Boy complements the latter two studies particularly well in its focus on the tongzhi movement, family life and the emergence of queer space.[4] Kong's work raises important questions about the way Chinese gay men engage with the realities and constraints of social/family/queer life in urban China in which the State is always a highly present factor. In a similar vein the 'authoritarian' State is ever present and felt in Lynette J. Chua's recent monograph Mobilizing Gay Singapore: Rights and Resistance in an Authoritarian State in which she carefully maps the emergence and development of the gay rights movement.[5] Finally Benjamin Law's much lighter, at times even frivolous, work of non-fiction Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East will be used to engage more broadly with the (im)possibilities of a queer Asia.[6]

-

The idea of a queer Asia takes its inspiration from the idea of discussing non-normative sexuality and gender cultures as well as identities and practices within the context of being in and/or belonging to Asia. The website of Hong Kong University Press' Queer Asia series[7] quotes Travis S.K. Kong's hope that the series will enable increased intellectual traffic among Asian countries, breaking away from the more common flows between Asia and the West. As such the idea of a queer Asia clearly aims to deviate and in a sense disrupt the dominating presence of North American and European queer studies and theory.[8] Yet a question which inevitably emerges out of this otherwise laudable endeavour is 'Asia' itself, as James Welker puts it having reviewed a number of earlier publications that came out in the Queer Asia series: 'The field of Asian queer studies has thus far been constructed in such a way that frequently seems to presume a relatively bounded and unified notion of Asia, whose borders generally encompass East, Southeast, and, if to a somewhat lesser extent, South Asia.[9] A glossary exploration of recent news on LGBT-related issues underlines the complexities that come with thinking of Asia as one region.[10]

-

In December 2013 India's Supreme Court overturned the 2009 Delhi High Court decision to decriminalise homosexuality and thus reinstate article 377, a relic from colonial days initially introduced in 1860. The unexpected decision was met by disbelief not just by gay rights supporters but also by several high-profile politicians among which was Sonia Gandhi, President of the Indian National Congress Party and at the time leader in the coalition government. Four months later however the same Supreme Court made the landmark ruling to recognise transgender people as a third gender. In its statement it emphasised that 'it is the right of every human being to choose their gender.'[11] Neighbouring Nepal had already decriminalised gay sex in 2007; however in 2011 political change brought with it rumours that the new Government would be seeking to recriminalise it. More recently though, the current minister for law, justice and parliamentary affairs assured the press that they would soon introduce a bill which would grant equal status to heterosexual and homosexual relationships, effectively opening the way towards gay marriage.[12] The opposite seemed to be going on in oil-rich Brunei. Early 2014 its Sultan announced that it would start implementing a new Sharia-based penal code which in 2015 would make sodomy punishable with death by stoning. China which decriminalised homosexuality in 1997 but offers no further support in terms of recognition of relationships or rights to adopt suddenly started clamping down on same-sex themed fan fiction in 2014 claiming that it essentially concerned pornographic novels that promote homosexuality.[13] Japan, which itself has no history of hostility towards homosexuality,[14] remains a divided country in terms of acceptance yet saw the First Lady of Japan join the festivities of the LGBT pride parade in Tokyo in April 2014. Finally, Singapore, where homosexuality remains illegal under a similar colonial relic as India (section 377a), witnessed its largest 'gay rights rally'[15] in 2014 with over 26,000 participants. Yet the growing popularity of gay rights has also started giving rise to dissent from religious groups; over 6,400 Christians dressed in white attended a family worship service to protest Pink Dot.[16] A month later the pulping of a number of children's books by the National Library, one depicting the story of two male penguins raising a baby chick in the Central Park zoo, led to considerable discussion in the media over what constitutes (traditional) Singaporean family norms.

-

While the above makes an ostensibly easy point about the diversity of happenings in the 'queer' Asia region and its inherent 'impossibility,' it also underlines that when it comes to Asia there is much to discuss in terms of LGBT-related matters. What follows is an exploration of several recent publications on China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and 'Gaysia' as a whole. Deviating from the more traditional academic review I have read these volumes mainly with the question in mind about how they complement, contrast and converge with each other in light of issues of representation and recognitions, activism and identity politics. What questions do they address and which do they raise? Considering this, what potential research agenda emerges?

Adventures in the queer East

-

In Gaysia, Benjamin Law opens by stating that 'of all continents, Asia is the gayest.'[17] It is not particular clear what reader (from East or West) he has in mind but Law continues: 'Deep down, you've probably had your suspicions all along, and I'm here to tell you those suspicions are correct.'[18] As he summarises neatly: six of the ten most populous countries are in Asia (seven if you include Russia) and as such they are: 'sharing one hot, sweaty landmass and filling it with breathtaking examples of exotic faggotry.'[19] The author is perfectly aware of the generalisations he makes though also adds that after a year of travelling around seven Asian countries (China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand) that is what one invariably ends up doing. Ethnically Asian (born of Hong Kong immigrant parents) yet Australian by nationality (and based in Brisbane) he felt 'it was time to go back to my homelands' and by doing so 'to reach out to my fellow Gaysians: the Homolaysians, Bimese, Laosbians and Shangdykes.'[20]

-

Throughout Gaysia the author refers to himself in both Asian and 'western' (Australian) terms, highlighting the bifocal way he experiences and engages with the idea of gay/queer Asia.[21] As such he produces a narrative which highlights a certain knowing of what constitutes 'Asian' and what problems LGBT-identities might see themselves confronted with in relation to being from and belonging to Asia. Yet as he is (also) Australian his perspective is distinctly 'western' as well, producing a text which in its categorisation (gay, lesbian, transsexual etc.) and associated issues/potential solutions mirror a western optic on such matters. While studies of queer Asia clearly show the influence globalising forces have had on local movements they are also critical for its disregard of local/cultural exigencies with respect to family life and normativities/legalities in which the State is often a controlling factor. Both Lucetta Yip Lo Kam and Travis S.K. Kong's work highlight this.

Shanghai Lalas & Chinese male homosexualities

-

In the introduction of Shanghai Lalas, Lucetta Yip Lo Kam recalls the first day of her ethnographic fieldwork in Shanghai. She was invited to a private party of lala women at a karaoke lounge and had been told that it would be a surprise proposal party between two women. She writes: 'The two lovers in the party were both in heterosexual marriages.'[22] Lala, she explains, 'has become a collective identity for women with same-sex desires and other no-normative gender and sexual identifications.'[23] Part of the larger tongzhi community, which comprises 'gays, lesbians, bisexuals, transgendered [sic], cross-dressers, transsexuals, sex workers, SM role players,'[24] the scene at the karaoke bar set the scene to explore what Kam refers to as the 'emerging tongzhi family.'[25] The term tongzhi itself has a transnational history; originally a product of communist China it travelled to Hong Kong and was reinvented there only to be reincorporated as a 'rejuvenated' public identity back in China. Literally meaning 'common will' it is usually translated as 'comrade' and was initially used as an encouragement to fight against the Qing imperialist regime in the early twentieth century.[26] In the early 1990s it got appropriated in Hong Kong by the LGBT community.[27] As a term its use is widespread and in its parlance covers the whole gamma of non-normative sexualities yet it exists alongside other terms such memba which is exclusively used by gay men in Hong Kong, a Chinglish play on 'member.'

-

Travis S. K. Kong's study on Chinese Male Homosexualities and Kam's ethnographic work on and among lesbian or 'female tongzhi communities' in urban China (mainly Shanghai), complement each other in the rich detail they provide of the way gay/tongzhi/memba communities developed historically as well as the issues they are faced with in the present. In its highly personal approach Kong's study is reminiscent of Parmesh Shahani's multi-sited ethnography Gay Bombay,[28] in which his own history as a gay man in Bombay allows him to reflect on the manifold historical and current dimensions that color Bombay's 'gay' map. In his aim to unravel the complexities of globalisation in the kaleidoscopic life of male homosexuals in China, Kong brings to the fore personal experiences which are not simply instances of ethnographic reflection but also actual moments out of Kong's life which reveal his own position as activist and 'gay' man. Kong's book which is divided in three parts, each with a distinct topographical focus—Hong Kong, London and China—initially focuses on the various dimensions of citizenship (sexual, consumer and intimate), but then departs from this to examine the lives of migrant gay men from Hong Kong in Britain and the formation of a queer diaspora, only to return to Asia where Kong finds himself confronted with what he describes as a 'new new China' and a 'new new tongzhi.' This new 'New China' needs to be understood in terms of the country's trajectory from Maoist 'rule of man' to the more modern 'rule of law' and the various economic and social reforms that have fuelled this transformation.[29] The 'new new tongzhi' is also description of a process: one whereby the arrival of a global gay identity, itself the product of the globalising and neoliberal forces, transforms the internalisation and expression of a local/Chinese gay identity, 'from that of a perverted subject to that of a new kind of human subject.'[30] Kong links this to the concept of cultural citizenship which he describes as one that is mediated through the idea of commonality, infused with minority claims and rights, and which ultimately centers on the idea of difference to which citizens given actively shape themselves.[31] In the context of China this 'new socialist citizen' negotiates between the collective sense of the people and that of being an individualised economic actor.[32] Yet as Kong also cautions this new hegemonic ideal of cultural citizenship is not accessible to all which as a result marginalises already marginalised communities such as 'money boys' and rural-to-urban migrants.[33]

-

Established tongzhi communities in Taiwan and Hong Kong and to a lesser extent communities in the West were also instrumental in the emergence and rapid development of lala communities in China, especially where those born after 1980 are concerned, as Lucetta Yip Lo Kam argues.[34] The Internet has played a prominent role in this development as it enabled social networking and information exchange and facilitated international, regional and local mobilisation efforts.[35] So-called lala-camps for instance also included veteran LGBTQ activists and scholars from Hong Kong, Taiwan and North America who engaged in cultural and political dialogue with local community members in China.[36] Perhaps more importantly however the Internet 'has acted as an accelerator to the emergence of identity-based sexual communities in contemporary China.'[37] Almost all Kam's informants first learned about homosexuality and community activities through the Internet. As such the Internet has dramatically changed the lives and ways of interacting when it comes to same-sex desires in China.[38] Threat of exposure and 'gay blackmailing' remains an issue though and the 'absence of recourses is exacerbated by the lack of legal recognition and protection of homosexual people in China.'[39]

-

Lucetta Yip Lo Kam's Shanghai Lalas is divided into five chapters of which the first discusses the shaping of lala communities. While the transnational dimensions outlined above played a prominent part in this in the shaping of these communities it is the local realities that stand out and that are further discussed in the subsequent chapters which revolve around public discussions, private dilemmas and negotiating the public and the private. As Kam argues, the (in)visible boundaries onto which one can project diverse ways of life and where one can locate oneself in terms of the changing contours of social acceptability is mediated by public discourse.[40] The discussion of homosexuality in medical texts, the treatment of it in the legal domain and the engagement of local academia were important factors in the way the public discussion took shape in the economic reform period. However, as marriage is still being assumed to be an uncontested and natural part of adult life,[41] many lala women still the (private) dilemma of how to deal with giving in to marriage. Heterosexual acting including self-monitoring of gender expression towards parents and other family members 'allows' lalas to survive in heteronormative spaces but brings considerable stress as well. As marriage is understood as an individual's obligation towards their family and so as not to upset the social order the pressure and reality of marriage is omnipresent.[42] Chugui (getting out of the closet, not understood as merely a verbal act but involving a long-term process and careful planning[43]); the importance of economic well-being bringing social respect (and being able to 'save' a person from a socially undesirable category[44]); heterosexual acting, 'cooperative marriages,' and living secret dual lives all play a part in the way lala women give shape and are able to give shape to their private and public lives. About this Kam makes an important argument that lalas are in fact doubly marginalised: as women they are not culturally recognised as autonomous sexual subjects (unless treated as deviants or as abnormal) while as tongzhi their same-sex desires are often trivialised.[45]

-

In the final chapters Kam brings the question back to the local by tackling the notion of Chinese tolerance of homosexuality which is usually defined in opposition to the physical expressions of homophobia in the West contrasting with a western imagination of a homophobic and backward China.[46] Yet as Kam argues the silent force of 'tolerance' effectively facilitates sexual regulation among Chinese families. Similarly while the project to normalise can be understood as a positive response to the institutionalised stigmatisation of homosexuals over the years, 'it can also be interpreted as part of a greater project to construct a new sexual morality for the newly capitalized and increasingly commodified society.'[47] It produces a narrative of understanding of what can be considered 'properly gay.' While in Kam's study this proper gay person is largely the product of the politics of public correctness,[48] internally the diversity among tongzhi communities is expanding and multiplying at great speed.[49] Recent online discussions on the applicability of queer theory to the tongzhi movements—one that was positioned as opposed to 'scientism' and the essentialisation of sexual orientation[50]—not just reminiscent of the larger questions with which the various communities grapple, but also how much more 'space' there is to engage with these questions.

Binaries and contact moments

-

In Contact Moments Katsuhiko Suganuma takes the binary East-West to explore the contact moments between Japanese queer culture and that of the West post-World War II. In particular his book is concerned with the way Japan's post-war male-queer culture has been realised through a comparative perspective with the West. Like Travis S.K. Kong his approach is deeply personal about which he states from the start: 'I would like to demonstrate my argument through reflection upon my personal life and experience.'[51] Having grown up in Okayama, he describes his youth as without much exposure to information on gay culture though he later came to realise that that there had always been popular gay magazines available in the local book store. Reflecting on the various binaries of local/global, self/other and us/them that inform cross-cultural analysis he argues that much of the writing on queer Asia 'forces us to realize the importance of rescuing subtle modifications and rearticulations of gay and lesbian identity in Asia even though it might look as if they were imported from the West in the age of globalization.'[52] Instead of seeing Japan as a passive recipient of western thought and culture Suganuma shows how ideas are modified in its manifestation and definition to reach local contexts.

-

Suganuma's study is structured in seven chapters. In the first chapter he engages with post-war perverse magazines and the way they constructed Japan's post-war identity in relation to the West in gendered and sexualised terms; an analysis which is continued in the third chapter which focuses on the first Japanese gay magazine and the way it gave shape to notions of Japanese male masculinities. Placing the discussion of whiteness or white masculinity at the centre of his analysis he examines how it was consumed and digested in a Japanese queer context.[53] The in-depth literary analysis of the memoir of an American's encounters with homosexuality, Orientalism and Japan, with which Suganuma continues in the fourth chapter, brings to light the importance of asking self-reflective questions about how our way of knowing other queer cultures is constantly shifting through the process of knowing and that we need to be aware of the shifting nature of our own subjectivity or perspective.[54] Making use of the concept of masking, he then goes on to show how the work of a Japanese gay rights organisation active in the 1990s might be construed as wearing a western/global mask while the mask worn by Japanese gay writer Fushimi Noriaki in his theorisation of gay studies may be thought of as Japanese/local. Both actually expressed similar sentiments about gay identity in Japan.[55] He extends this discussion in chapter six in his analysis of the way the local/global queer binary has become redefined and rearticulated as a result of the Internet.

-

In Suganuma's concluding chapter he returns to a theme which also underlies Kam's and Kong's work; the shifting dimensions of queer identity in the context of globalization,[56] in which the Internet plays such a dominant role. While we all acknowledge the trouble with binaries, he ponders, why our concerns with them never quite seem to go away? In Kong's work we encounter these concerns channelled into one theme relating to the pink economy and queer consumerism which are heavily informed by transnational middle class sensibilities and a global, hegemonic cult of gay masculinity.[57] Kam's study points at some of the impossibilities of western hegemonic constructs of an 'ideal type' queer life considering socio-cultural expectations. In relation to these dilemma's Suganuma argues that in the post-War period the contacts moments between Japan and the West 'were always entangled with diverse queer modes of being that exist in the realm of hybridity, a complex mixture of local and global currents.[58]

Striking a balance and pragmatic resistance

-

In his chapter on Japan, Benjamin Law examines the popularity of drag queens, camp gays and transsexuals on Japanese television. However, as he quotes one of his informants: 'Sure, there are gay characters on TV, but they are only characters.'[59] Most of his chapters strike a balance between the quirky chipper and the painful and problematic. While encountering a vast variety of 'Gaysians'—foreign nudist homosexuals in Bali, transsexual pageant participants in Thailand, fierce (queer) activists in India with nicknames such as The Doctor or The Godfather—he also touches upon issues of forced religious therapy in Malaysia, HIV-prevalence among (young) sex workers in Myanmar, and gay-lesbian alliance-marriages in China. Although Benjamin Law himself holds a PhD in television writing and cultural studies,[60] Gaysia is not an academic work nor does he pretend it to be. While it may not be of major significance to the growing body of work on queer Asia that the other books I discuss are part of it is likely that this book will far outsell any academic work on the topic and is thus likely to make an impact on the way a gay (queer) Asia is imagined. Notably absent in his book is Singapore, Asia's smallest nation and one whose engagement with homosexuality has struck a precarious balance between pragmatism and family-focused moralities. Two recent volumes discuss the tension that exists between the two at length.

-

In Mobilizing Gay Singapore Lynette J. Chua tells the history of the gay rights movement in Singapore. The central concept of the book is 'pragmatic resistance' in relation to which she examines the movement's emergence, development as well as its strategies and tactics over time. Section 377A of the Penal Code which criminalises 'gross indecency' between men effectively continues to make homosexual acts illegal in Singapore. While this not only makes it difficult to claim support on a variety of fronts—for instance being eligible for public housing in which the majority of Singapore's population lives—it also shapes and influences public perception of what is thought of as 'gay' lifestyles. Furthermore Singaporean media is banned from carrying content that ostensibly promotes, justifies or glamorizes LGBT-'lifestyles'.[61] While Chua's book is critical of the State's involvement in and perspective on the matter, the historical development of 'mobilizing gay Singapore' also strikes a hopeful chord. Pink Dot, Singapore's annual gay pride event—although actually not referring to itself as such, instead opting for the less-problematic slogan 'Supporting the freedom to love'[62]—has considerably grown in size in recent years.

-

Starting with the question of how to mobilise gay rights under authoritarian rule, Chua reflects in chapter three ('Timorous Beginnings') that when Singapore's economy started growing this also gave rise to a better-educated middle class which started to question the People Action Party's (PAP's) dominance and demanded greater accountability.[63] While space for this was limited, the 1980s did see the awakening of a political consciousness and also gradually the emergence of a gay movement. In subsequent chapters Chua unravels how Singapore's gay movement developed further and in particular the role the Internet played in this process from the late 1990s onward. While the Internet was perceived as a safety zone, especially in terms of the lack of a physically present organisation which may be perceived as political and thus problematic by the State, members of the gay movement were also well aware that 'the potentially dubious legality of Internet organizing … could toe the line or limits of the political norms that constrain political mobilization.'[64] While in its transition period from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s top-PAP politicians started making gestures toward greater acceptance (though administrative decisions continued to hold back gay organizing[65]), it is the tension of walking a thin line between what is allowed and what might be potentially problematic that runs a red thread throughout Chua's narration of developments. Pink Dot is probably the most interesting and important example in this regard. Every year Pink Dot is held at the Speaker's Corner (an area located in Hong Lim Park), which is the only place in Singapore where citizens and permanent residents may demonstrate, hold exhibitions and performances and speak freely on (most) topics. The event can be interpreted as a pragmatic way of resisting opposition from, for instance, Christian movements and the authorities, which have (partly successfully) intervened in earlier attempts at organising gay rights events such as a Pink Picnic and the Pink Run. The fact that only Singaporean permanent residents and citizens can participate makes it a decidedly Singaporean event something which is further emphasised by the explanation of the use of the color pink which is said to be a blend of the red and white in Singapore's flag.[66] Finally the publicity material frequently underlines that Pink Dot is not a political event and as such also not a 'protest'[67] effectively removing what could otherwise be construed as potentially inciting unrest.

Gaysia: Queer Singapore in queer Asia

-

In the edited volume Queer Singapore, editors Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow bring together a set of papers which are united through the notion of illiberal citizenship. Not unlike Chua's pragmatic resistance, illiberal citizenship draws upon a notion of pragmatism that in the case of Singapore is underpinned by the logic of neoliberal postcolonial development.[68] Singapore's pragmatism rationalizes policy implication as natural, necessary and realistic[69] in relation to Singapore's vision on economic development, with its emphasis on science and technology and centralised 'rational' public administration on which the fundaments of its successful model of attracting international capital and business rests. Central to this is the logic of illiberalism which, at its core, embodies an ambivalence that on the one hand facilitated the emergence of a queer Singapore yet on the other hand also continues to inform a narrative of survival. The division of the edited volume of Queer Singapore in two parts also reflects this. The first set of papers focuses on issues of human rights, social movements and spatial politics and by doing so maps and documents the emergence of LGBT activism, its fight against repression and its impact on popular culture. The second part then brings together a set of case studies of cultural productions which shows how 'queer Singapore' has been discussed, displayed and dealt with in theatre, literature and popular culture.

-

The essays in Queer Singapore connect with themes and issues discussed in other recent publications on queer Asia as discussed above. Shawna Tang's essay on transnational lesbian identities in Singapore resonates with findings in Shanghai Lalas. While the case of Singapore warrants attention precisely because of its cultural location as one of the most globalised Asian cities, as Tang argues,[70] locating Singapore as inherently part of and in a sense produced by 'Asia' (in terms of values, norms and culture), also helps connect specific issues and struggles to more broader ones as experienced for instance by the tongzhi communities in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Similarly Roy Tan's engaging photo essay on the history of early gay venues in Singapore[71] opens with the question: 'Where could a young gay adult go to meet like-minded people in Singapore in the 1970s?'This question, which the author himself grappled with at the time, connects to the way Katsuhiko Suganuma explores how male-queerness was present and developed over time in Japan in Contact Moments. While ostensibly different studies, in essence they both deal with the visibility and emergence and presence of queer Asia in public space and popular culture.

-

Singapore envisioned as a 'Pink Dot' as opposed to the more common epithet for the nation as a 'Little Red Dot' provides a useful illustration for how on the one hand Singaporean queer-related issues are entirely the nation's own, yet on the other hand how it (in)directly points at shared or linked issues which (potentially) seem to justify the notion of a 'queer Asia'. In that sense queer Asia is not merely about breaking free from the perceived hegemony of western queer theory but also offers the potential to reflect on queer-related issues from an inter-Asian perspective. While the Asian-region is characterised by considerable differences in terms of political freedom, economic development and socio-cultural make-up, the region has also witnessed considerable intra-movement and migration which in an age of transnationalism now connects regions that previously were separated by geographical distance. While the volumes discussed above speak for themselves in terms of their urgency and relevance, it is typically in observations such as the way the tongzhi and lala identities in China took shape influenced by developments in Hong Kong and Taiwan that point to the direction that the field of queer Asian studies could take in its subsequent steps. Now that it has been established that there is a need for such a field in opposition to dominant/hegemonic western queer theory, the question that emerges is how can we conceptualise and theorise further on the idea of queer Asian identities in relation to each other. As can be concluded from above-mentioned studies, while the Internet has made it considerably easier to organise and form alternative communities, it has also facilitated the transnationalisation of movements and thus the possibility to reflect on one's queer identity from a transnational perspective. It will be interesting to see how the formation of queer Asian identities will continue to develop in the years to come—not just in relation to developments in their respective countries but also in relation to developments elsewhere in Asia.

References

[1] Katsuhiko Suganuma, Contact Moments. The Politics of Intercultural Desire in Japanese Male-Queer Cultures, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

[2] Lucetta Yip Lo Kam, Shanghai Lalas: Female Tongzhi Communities and Politics in Urban China, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013.

[3] Audrey Yue and Jum Zubillaga-Pow (eds), Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

[4] Travis S.K. Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities: Memba, Tongzhi and Golden Boy, New York: Routledge, 2011.

[5] Lynette J. Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore: Rights and Resistance in an Authoritarian State, Singapore: National University Press, 2014.

[6] Benjamin Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, London: Random House, 2014

[7] 'Book Series: Queer Asia,' Hong Kong University Press, online: http://www.hkupress.org/Common/Reader/Channel/ShowPage.jsp?Cid=14&Pid=4&Version=0&Charset=iso-8859-1&page=0&cat=13 (accessed 4 September 2014).

[8] James Welker, '(Re)Positioning (Asian) queer studies,' GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies vol. 20, nos 1–2 (2014): 181–98, p. 182.

[9] Welker, '(Re)Positioning (Asian) queer studies,' p. 195.

[10] I prefer to use the abbreviation LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) as opposed to recent additions of Q (queer) and/or I (intersex) not so much because I don't think these categories should not be included but because by now LGBT has become a widely recognised term also among the public at large for whom it has come to stand for the diversity of categories. As such the individual meaning of the letters has become less important.

[11] 'India court recognises transgender people as third gender,' BBC News India, online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-27031180 (accessed 4 September 2014).

[12] 'Nepal to legalise homosexuality and same-sex marriages, says law minister,' Scroll.in, online: http://scroll.in/article/674232/Nepal-to-legalise-homosexuality-and-same-sex-marriages,-says-law-minister/ (accessed 4 September 2014).

[13] See for instance: 'Inside China's insane witch hunt for slash fiction writers,' BuzzFeed, online: http://www.buzzfeed.com/kevintang/inside-chinas-insane-witch-hunt-for-slash-fiction-writers#yulfc3 (accessed 4 September 2014).

[14] It was illegal for a brief time from 1872–1880. 'This coincided with the second French Military Mission to Japan. The provision of restricting anal sodomy was repealed by the Penal Code of 1880 in accordance with the Napoleonic Code.

[15] Please note that Pink Dot actually does not refer to itself as a gay rights rally and avoids using words such as 'protest' instead promoting itself as an organisation that 'supports the freedom to love.'

[16] 'Thousands of Singaporean Christians wear white to protest Pink Dot gay rally,' Yahoo! News, online: https://sg.news.yahoo.com/thousands-of-singaporean-christians-wear-white-to-protest-pink-dot-gay-rally-143235694.html (accessed 4 September 2014).

[17] Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, p. 1.

[18] Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, p. 1.

[19] Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, p. 1.

[20] Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, p. 2.

[21] Benjamin Law uses gay, queer and LGBT erratically, usually depending on the context.

[22] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 1.

[23] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 1.

[24] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 1.

[25] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 1.

[26] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 14.

[27] In 1991 the first gay and lesbian film festival was held in Hong Kong and named the Tongzhi Film Festival.

[28] Parmesh Shahani, Gay Bombay: Globalization, Love and (Be)longing in Contemporary India, New Delhi, London, Los Angeles, Singapore: Sage, 2008.

[29] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 172.

[30] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 146.

[31] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 169.

[32] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 169.

[33] Kong, Chinese Male Homosexualities, p. 173.

[34] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 21.

[35] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 21.

[36] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 21.

[37] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 27.

[38] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 28.

[39] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 29.

[40] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 40.

[41] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 60.

[42] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 63.

[43] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 74.

[44] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 78.

[45] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 71.

[46] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 89.

[47] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 98.

[48] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 90.

[49] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, p. 106.

[50] Kam, Shanghai Lalas, pp. 107–08.

[51] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 2.

[52] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 26.

[53] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 29.

[54] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 31.

[55] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 32.

[56] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 181.

[57] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 199.

[58] Suganuma, Contact Moments, p. 185.

[59] Law, Gaysia, p. 149.

[60] According to his website: Benjamin Low, online: http://benjamin-law.com/ (accessed 4 September 2014)

[61] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 39. Both Singapore and India still make use of the same British Penal Code. In Singapore the issue is specifically with Section 377A ('Outrages of decency') which is the remaining piece of legislation after the 2007 review of the Penal Code. Oral and anal sex between heterosexual partners was then decriminalized but article 377A was kept so that it would remain illegal for men to engage in such acts. In India the full article 377 is still in effect though not actively reinforced.

[62] See PinkDot.sg: Supporting the Freedom to Love, online: http://pinkdot.sg/, accessed 4 September 2014.

[63] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 46.

[64] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 71.

[65] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 80.

[66] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 130.

[67] Chua, Mobilizing Gay Singapore, p. 129.

[68] Audrey Yue, 'Introduction: Queer Singapore: A Critical Introduction,' in Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, ed. Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012, pp. 1–28.

[69] Yue, 'Introduction: Queer Singapore: A Critical Introduction,' p. 5.

[70] S. Tang, 'Transnational lesbian identities: Lessons from Singapore,' in: Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, ed. Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012, pp. 83–96, p. 84.

[71] R. Tan, 'Photo essay: A brief history of early gay venues in Singapore,' in Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, ed. Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012, pp. 117–48.

|