a photo essay by Tony Whincup

Mwaie Chant (00:02:52, mp3, 5.4mb)

Click on pictures for captions. |

|

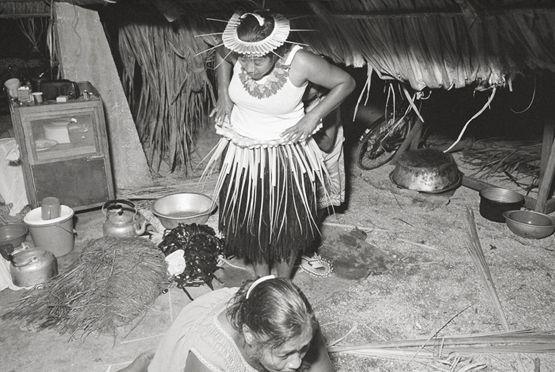

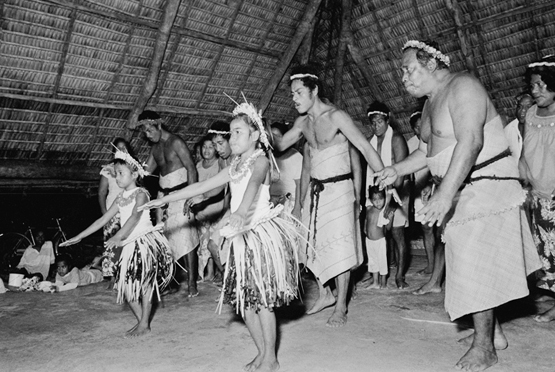

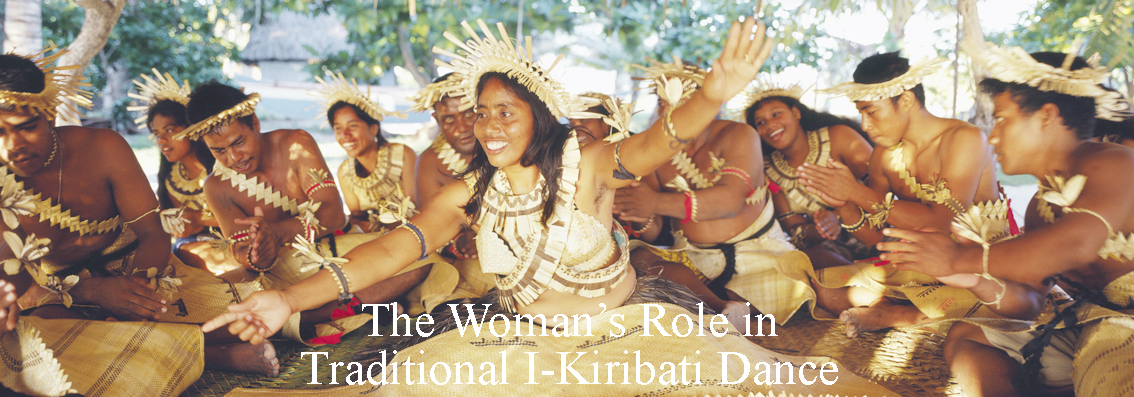

The following photographic essay focuses upon the role of women in traditional I-Kiribati dance, te mwaie. The images draw attention to the context in which the women operate, the materials with which they engage, their relationships with others and emotional aspects of dance performance. Each group of images is clustered around a particular theme: the first the atoll context, followed by material preparation, then the primary site of the dance performance—the meeting house, te mwaneaba, practice and preparation and finally performance and associated emotional expressions.

The photographs are based on the belief that ethnographic understanding proceeds from a tentative assessment of context by reference to its constitutive parts. This action redefines the context and furthers understanding of the particular, gradually spiraling outwards to the limits of interpretation. The tangible objects that comprise the photographs are understood and have meaning as a part of the I-Kiribati social system. It is in the inter and intra relationships of these objects, isolated and united by the photograph's frame, and between the images themselves that a social interpretation is developed. The unique combination of images aims to produce a holistic reading greater than the some of its parts. To begin to understand something of the significance of gender roles in te mwaie it is necessary to understand gender construction in the day to day I-Kiribati existence where male and female roles are, in general, clearly defined and maintained. Men build canoes, cut te karewe (coconut toddy), go fishing and build houses. Women make string and thatch, weave, look after the children and cook. The man has the authority and power in both home and meeting house. Dance is an exception to the clear gender definitions maintained in I-Kiribati society. Dance is a domain in which power, authority, sexuality and practices become blurred—gender differences are not so clearly defined. Many of the roles within dance are common to both men and women and are seen to have equal importance. Differentiation that is maintained is seen in a small number of gender specific dances and costumes. The strict control adhered to for body positions and movements, and the inter-changeability of most dances for the sexes, provides a strong contrast to the often overtly sexual and gender differentiating performances of many Polynesian dances. I-Kiribati women though are still thought to be at their most attractive when dancing well and there is the potential for spousal jealousy even when permission or encouragement to dance has been given by the husband. Dance also necessitates that women 'stand out' and be 'looked at' during their performance, a practice that would not be tolerated outside the confines of dance and is in sharp contrast to the norms of I-Kiribati behaviour. The adoption of such a strongly differentiated role produces great tension and strong emotions for both men and women performers. Women are vitally involved in all aspects of te mwaie—they can be teachers, organisers of dancing teams and of performances themselves, and they also produce the costumes and decorations, which are an essential part of the dance. The experience with particular objects and associated practices of dance provides an intergenerational link and the sense of 'being' an I-Kiribati woman. She is united here with other women who share and understand

|

these experiences. Her involvement in te mwaie can be seen as a part of her extended self and a part of her socialisation as an I-Kiribati. The women's contribution both as performers and in providing choral and rhythmic support is fundamental to any dance occasion.

Dance for the women of Kiribati is a significant activity in all aspects of production and performance. This domain endows women with a powerful vehicle for self-definition and self-recognition, both as individuals and as part of a social group. A dialectic relationship exists between women and te mwaie in which each develops an enduring social significance in a practice that lies at the heart of what it is to be I-Kiribati. I-Kiribati traditional dance includes the principal dancers, who are carefully selected, rehearsed and immaculately dressed and decorated, and a chorus, which comprises anyone from the youngest to the oldest in the village joining in to provide a rhythmic and melodic framework. The melodies are generally sung in unison. Stamping of feet on the floor of te mwaneaba and the clapping and slapping of dancing mats with the palm of the hand provide a rhythmic accompaniment. Dancers and the chorus are structured as two strongly contrasting parts of the one performance. The dancers are to remain seemingly aloof, as they repeatedly retrace their precise and controlled movements in contrast to the mounting energy and passion of the chorus. The performance can be seen as a struggle between the opposing forces of static and dynamic values. The dancers embody the static values of control, historical patterns and established expectations, whereas the chorus responds creatively and interacts spontaneously. The tension between the two is exquisite for both the performers and audience. To be properly understood, the significance of the dance performance must be seen against its social context. In Kiribati, overt and individualistic behaviour is frowned upon. During the dance though, performers become the focal point of attention. This in itself is unusual, and the intensity of the moment is heightened by the lengthy preparations for the performance and the social significance of the venue. Dance provides a rare and socially acceptable opportunity to publicly express emotion and individuality. It can convey

|

|

|

The Republic of Kiribati is a chain of coral atolls straddling the equator approximately halfway between Hawaii and Australia. The reefs are the defence against relentless waves upon these precarious landfalls. There is nowhere, not even in the centre of the lagoon, that the incessant roar of the breakers is not heard. These tiny ribbons of coral with no fresh surface water and thin, infertile soil are the home of the I-Kiribati. It is hard not to experience the immensity of the isolation of these islands. Traditionally the spirits, te anti, were an omnipresent part of existence and for many their presence is still recognised today.

|

In Kiribati most of the objects used in day-to-day life are made from local materials that are found in the immediate vicinity of the villages and prepared by the communal skills and effort of the family. Inevitably, with the limited resources available and the imperatives of survival, an emphasis on functionality and simplicity of form has resulted. Much of the success of the I-Kiribati communities arises from their ability to exploit the potential of available materials for a wide range of purposes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Traditionally te mwaneaba is the social nexus of village life. It is in this structure that village decisions are made by unimane, whose seating positions declare their authority and status within the community. Te mwaneaba is the site of significant social activities such as traditional dance. It is a place of dignity and formality. There is an inter-relationship in which the activities in te mwaneaba are imbued with stature and significance, and which in turn define te mwaneaba as a place of power and authority.

|

The practices within te mwaneaba are significant in the way each reflects and constructs the other. For example, mwaie has historically been imbued with considerable authority by being performed in te mwaneaba. The special quality of the site enhances the feelings of the dancers and audience, heightening the tension and emotions of the performance. The dance brings together the village, historical procedures, spirituality and strong emotions, which in turn construct the social significance of te mwaneaba through its presence.

|

|

|

|

' … this is our culture and identity, we are known as I-Kiribati from the way we dance … That is why I love my traditional dance very very much. I love it because it is my identity.'[49]

|

Endnotes

[1] Figure 1. Te bino deals with lyric poetry and particularly themes of love; it can also be heroic especially for honouring distinguished groups of people. Both dancers and chorus are seated for te bino and it can be performed by men or women. The movement is in the head, arms and body, while the legs remain crossed. The feet are crossed flat, one foot fitting into the thigh and the other on the floor, so that te kabae, the dancing mat, will lie properly. Place: Abatao, North Tarawa, Kiribati, 1998. [2] Mea, Bishop Paul, Kiribati: Teaorereke, South Tarawa, 1999, original tape recording, transcript and translation held by author.

[3] Figure: 2. Coconut palms, pandanus and breadfruit trees have adapted to the sandy soil of the atolls. I, giant swamp taro, needs careful tending. Place: Abemama, Kiribati, 1998.

Bibliography Bailey, E., The Christmas Island Story, London: Stacey International, 1977. Carmichael, P., and J. Know-Mawer, A World of Islands, London: Collins, 1968. Coates, A., Western Pacific Islands, London: Corona Series, HMSO, 1970. Collective Authorship, Kiribati, Aspects of History, Kiribati: Institute of Pacific Studies and Extension services of the South Pacific and the Ministry of Education Training and Culture, Kiribati Government, 1979. Grimble, A.F., Tungaru Traditions, Writings on the Atoll Culture of the Gilbert Islands, Hawaiˈi: University of Hawaiˈi Press, 1989.

Grimble, A.F., A Pattern of Islands, London: John Murray, 1952.

|

|