Angles: Thank you very much for letting me interview you today. Why don't we start from the beginning? From reading your autobiographical work Jū-ni no enkei [Twelve Perspectives], it seems that you became aware of your own sexuality at a very early age.[1] Can you talk a little bit about your earliest experience?

Takahashi: Sure, at that time, I was living in Kyushu. One day, I was walking down the street when a man came over and beckoned to me to walk along with him. As we were crossing a bridge over a river, he started to touch my penis and showed his to me. I became very aroused by that. I really liked the man. I suppose I was about four at the time. I still remember his name clearly. His name was Egawa Hiroaki-chan.[2] [Laugh]

Angles: I wonder if we would cause trouble for him if we put his name in print ... [Laugh]

|

|

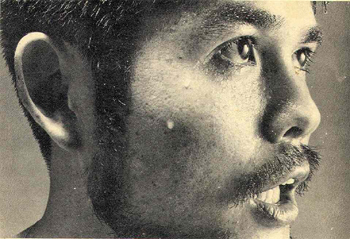

Figure 1. Takahashi Mutsuo and Jeffrey Angles in Takahashi's garden on the day of the interview. Photo by Hanzawa Jun

Figure 1. Takahashi Mutsuo and Jeffrey Angles in Takahashi's garden on the day of the interview. Photo by Hanzawa Jun

|

Takahashi: Well, he probably has passed away by now. He was about ten years older than I was. Actually, he was in grade six then, so perhaps he was only around eight years older.

Angles: Did that sort of thing continue?

Takahashi: Well, after the first experience… How should I put this? I was really fond of older boys, you know, the male upperclassmen at school.

Angles: You also had a relationship with your uncle, didn't you?

Takahashi: Well, that was really more psychological one, I guess. [Brooding] Well, I guess you could say that it was more or less the same. [Moment of silence] Yes, I suppose it really was rather like the others…

Angles: Reading your memoirs Jū-ni no enkei, and your essays 'Osanai ōkoku kara' [From the Kingdom of Youth], it seems clear that your uncle really was an important figure in your life.[3]

Takahashi: Indeed, he was really important to me. But who knows? Perhaps I have just blown him up to unusually large proportions in my memory.

Angles: Can you tell me more about the things you did in Kyushu where you lived? Were there some places for you to hook up with other sexually like-minded people?

Takahashi: Not really. There might have been some, but I didn't know about them then. I had relations with a couple of men whom I met there and some schoolmates when I was small, but I never went to places where men would go to meet each other. Maybe there were some, but I didn't know about them. When I first came to Tokyo, I found out that such places exist. And ironically, it was in Tokyo that I heard that such places exist in Kyushu as well… [Laugh] That's how I eventually made my way to those places in Kyushu, but when I was living there, I had no idea they even existed. But anyways, I was really interested in that sort of activity. That's why I wrote so much work, especially poetry, about it.

Angles: Can you tell me what you thought when you saw those places in Tokyo for the first time?

Takahashi: In Tokyo, I was stunned by the huge number of bars, movie theaters, and saunas where - what should I call them? - gay people would gather. And you know I was young back then, so once I got to know those places, I became a repeat customer. [Laugh]

Angles: [Laughing] I see. Were all those places in one specific area or were they scattered around the city?

Takahashi: They were all over. Some were near the Ginza; some were in other places like Shibuya, Ueno, Asakusa, Ikebukuro, and Shinjuku. They were all over. And not to mention, people sometimes did things inside of trains too. Trains were extremely important places for us, although I'm not sure if one can call them 'places.' Maybe 'moving places'—shall we say that!? [Laugh]

Angles: You described one such train full of homoerotic activity in one of your novels, Zen no henreki [Zen's Pilgrimage of Virtue].[4]

Takahashi: Most of the places I describe in that novel were places that I actually visited.

Angles: Really? Yet many things that you describe in Zen no henreki are so surreal they couldn't possibly be real, could they?

Takahashi: Of course not. But there was always a kernel of truth that reflected my own experiences. Back then, there was no fear of AIDS or anything so people went ahead and did whatever they wanted… [Moment of silence] There were places where people gathered to seek sexual contacts, but sometimes, it just happened in other places too… For instance, you might just start doing things with someone in the elevator of a department store in the Ginza, or someone might pick you up on the street, and so on.

Angles: You say that people would just pick each other up, but how did they do that? Were there certain buzz words or something that people would use to get the message across?

Takahashi: Well, you know, someone might start by saying something like 'Want to go grab a cup of tea?' Then somehow our conversation would end up turning to what we really wanted to talk about.

Angles: I see. Anyway, you published your anthology of poems, Bara no ki, nise no koibito-tachi [Rose Tree, Fake Lovers] after you moved to Tokyo, right?[5]

Takahashi: At the time, I was really interested in homoeroticism so most of my poems ended up being about that subject. When I collected them and thought about putting them together as a book, I asked [the prominent contemporary poet] Tanikawa Shuntarō if he would be willing to write an essay for the book. I just ran into him one day and decided on the spot to ask. He was kind enough to take me up on my request. Yet in his essay, he wrote that my anthology had been written by a gay man for gay men. At first, this left me speechless because I didn't really have that in mind when I was writing my poetry. I was just writing in a way that came naturally to me. Later on, I was told by people from various countries that my book of homoerotic poetry came at an unusually early point in world literature. It was a time when not many books like that were available. When I heard that, I wondered if it was true. Anyway, when I put the anthology together, that wasn't what I was thinking about at all. The collection just came together naturally.

When I published it, I sent copies to various people. Among them was the novelist Mishima Yukio. One day I got a telephone call. It was he saying he wanted to meet me in person.

Angles: Mishima called you out of the blue?

Takahashi: That's right. After that, we got along quite well, and he even wrote a long essay to include in my next anthology of poems.

Angles: Can you describe your relationship with Mishima? Was his relationship toward you like that of mentor or was it something else?

Takahashi: It is hard to describe. I thought of him as my literary senior. In Japanese there is a word called keiji which indicates the kind of respect that you have toward a senior - not the kind of respect one finds in a mentor-student relationship, but the kind of respect one feels toward an older brother. I think that word best explains my relationship with Mishima. He was a person who—how shall I put it?—thought that literature was not something you could teach; it's more something you have to acquire on your own. Instead, what he taught me had to do with how to get along with people, how to interact with society, and that kind of thing.

Angles: So then, Mishima didn't actually edit or make suggestions to your works at all?

Takahashi: Not at all. When he was young, people sometimes helped him out with his works. In my case as well, editors did a good amount of revision on my works. You find that sort of thing a lot in the Japanese literary world, but in the postwar period at least, literary mentors don't do that sort of thing very much.

Angles: [The critic and essayist] Etō Jun also wrote glowingly about your collection Bara no ki, nise no koibito-tachi, didn't he?

Takahashi: That's right. He had a review in the newspaper Asahi Shinbun back then, and he wrote about my collection of poems. He wrote some nice comments about my work. For instance, he praised my work as a significant 'anthology of homosexual poems.' At the same period, there was another review column in another paper, the Tōkyō Shinbun, that was written by an anonymous writer. According to Mishima, that writer was Shinoda Hajime. Now, Shinoda and Etō Jun were on horrible terms with one another. Mishima once praised me by saying, 'Even though those two hate each other's guts, they were unanimous in their praise for you. That's a sure sign that you can go ahead and think of yourself as talented!' [Laugh] Of course, Mishima also praised my work highly.

Angles: Speaking of the review column by Etō Jun, I heard that he included your photo alongside the article. That was quite rare, wasn't it?

Takahashi: Yes, it was. You might find photos of writers in his review time to time, but he never wrote about poems. Most of the reviews were about novels. That was a general pattern in the world of Japanese literary reviews—lots of reviews of fiction, but not poetry. Therefore, when a review of my poetry appeared in the newspaper with my photo, it probably surprised a lot of people.

Angles: Do you think the reason for that surprise was related to the rareness of the theme of your work?

Takahashi: That was part of it, but rather than the theme, the review emphasized the literary excellence of the work itself.

Angles: I see. After getting to know Mishima, he must have introduced you to various friends of his.

Takahashi: Sure. He was a kind fellow so he put me in touch with many different people. [The essayist, novelist, and translator of the Marquis de Sade] Shibusawa Tatsuhiko was one of them. I encountered many people thanks to him.

Angles: It seemed as though you and Mishima were surrounded with people who had a special interest in matters of sexuality - people like Shibusawa Tatsuhiko, [the contemporary female poet] Shiraishi Kazuko and others. In a way it seems like you formed a little salon of people interested in 'literature of the flesh.' Is that a fair way to describe it?

Takahashi: I'm not entirely sure, but our literary interests naturally did move in that direction. Until that point, that subject hadn't really been brought out into the open all that much in Japan. Given that situation, we were interested in bringing the subject to the forefront and not hiding it.

Angles: You were quite close to Mishima at the time that he committed his dramatic suicide [by ritual disembowment] in 1970 [on the grounds of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces]. Since you were so close to him, I wonder if you had any sense that he would do something like that…

Takahashi: Actually there was something that, when viewed in hindsight, did seem to be foreshadowing his suicide. It was about two months before he died. Mishima asked me out for a drink one night with Morita Masakazu, the boy who also committed suicide along with him. So we all went out and had a bite of blowfish to eat.

I came a little late, and by the time I got there, the two of them were already drunk and had bright red faces. Mishima spoke to me with an attitude that seemed to say, 'You finally made it, eh?!' Then he said, 'This guy sitting right here… There's a chance he's going to die sometime soon, but who knows? Maybe he'll keep on living until he gets to be a boring old man. However, this twenty-five year old lad Morita is a man worth remembering.' He went on to say, 'I thought long and hard about whom I wanted to remember him, but you are the only one for the job. Today, I want Morita to tell us about his life story—to tell us things I've never heard before.'

I just sat there listening. At the time, I thought it was all just talk, but Mishima was really hinting what was going to happen, but I wasn't sharp enough to catch the hint. Morita started talking about his childhood, but because I was drinking, unfortunately I don't really remember too much of what was said. Later, when Mishima and Morita committed suicide together, I realized that Mishima's behavior was all a sign for me of what was to come.

That day, after we finished our drinks, we ended up going to a sauna.

Angles: The three of you?

Takahashi: Yes. There was this place called 'Sauna Misty' in Roppongi where we went. We all stripped and got in. Then Mishima asked me, 'So, what do you think of Morita?' [Laugh] I replied, 'Well, he's a very attractive young man.' Mishima then said, 'But he is bit chubby… Got a bit of baby fat, eh?' So I told him, 'Maybe, but he's still a very attractive young man.' So Mishima said, 'Alright then, you two ought to go home together tonight.' [Laugh] Then I said, 'No, I couldn't do that!' [Laugh]

Angles: [Laughing] So how did Morita react?

Takahashi: Oh, this was all while Morita was off washing himself somewhere else. [Laugh] On the way back home, Mishima said, 'Come on, you say you couldn't ever do it?' When he started to take his leave of us, I said that I was also going. Right then, Morita shook my hand and said, 'Takahashi, I've never met someone like you in my life.' I still don't know exactly what he meant by that. For him, Mishima was probably more of a political and philosophical companion rather than a writer. So maybe he meant that he had never met a writer like me before. At least, that's the only way I know to make sense of his words, but I'm still not quite sure. I just remember what he said. I also remember how beautiful the stars were in the sky that evening. [Moment of silence]

After Mishima's death, I thought it was good Mishima had died the way he wanted. That was how it should have been. But I do think it was wrong that he got Morita all wrapped up in his death. Morita was only in his mid-twenties, and his future was full of potential, but Mishima took it all away. I don't think Morita died understanding all of what Mishima was about.

Angles: Do you mean that you don't think that there was any sexual tension between Morita and Mishima?

Takahashi: After Mishima died, a doctor involved with the autopsy leaked the story that Morita's sperm was found in Mishima's rectum. That story made the rounds in the press. I cannot prove or disprove that rumor, but there were articles about it in magazines, some of which were signed by the authors, so there might have been some truth to the story. If so, it is possible that Mishima thought of the act as a sort of ceremony that celebrated the bonds between the two of them as men, and Mishima told Morita what to do. But I don't think that Morita had 'those' kind of tendencies at all.

Angles: I see. Well, nowadays when people talk about Mishima's suicide, people often say that his attraction to the world of masculine eroticism played a large part in his decision to commit suicide. What is your reading on that?

Takahashi: Rather than just chalking up his manner of death to his homosexual tendencies, I think that there are other elements of his personality that can help explain his suicide. He did not have much a sense of being alive. That's why he behaved in such an eccentric fashion, and of course, the magazines carried lots of stories about his strange activities. When he saw his portrait reflected in those magazines, he managed to feel for a moment like he was indeed alive.

Angles: In a sense, you seem to be saying he was a narcissist.

Takahashi: Yes, he was. He was a person who wanted to feel as if he was alive. When he slashed open his own belly at the end, that moment of unbearable pain probably gave him a strong sense of being fully alive. Ironically, by that time, he was already half-dead.

In a way, he was a very unhappy man. From the time he was very young, he was always thinking about dying, and he wanted to do it—how shall I put it?—in an extremely decorative way. That's why he wrote about death so much in his literature. By giving his death a political dimension, he was making his death all the more decorative. [Moment of silence] And of course, by getting a young man wrapped up in death with him, he made his death that much more decorative.

Angles: So you are saying that his death didn't have anything at all to do with right-wing sympathies?

Takahashi: Probably not. But he used to say, 'If you compare the right wing with the left, left-wingers aren't the least bit erotic.'

Angles: [Laughing] I see.

Takahashi: He used to say, 'right-wingers are really erotic, but those left-wing guys aren't at all.' That's what he felt deep inside. It's rather strange how he didn't find the intelligentsia at all sexually appealing. In his novel Kamen no kokuhaku [Confession of a Mask], there is a simple, artless night-soil man who comes to clean out the latrines. That kind of down-to-earth figure really seemed to hold an erotic appeal for him. He found eroticism in that kind of person but not in people like his classmates and so on.

Angles: Let me change the subject a little. You were a good friend of a photographer, Yatō Tamotsu, weren't you?

Takahashi: Yes, we were close. Mishima introduced him to me in the years before he died. We continued to see each other fairly often until Yatō passed away.

Angles: He is a photographer who is certainly worth re-evaluating, don't you think?

Takahashi: I agree. That needs to be done. You know, he used to be a movie actor. Maybe it was about the time he became an actor, or maybe it was before, but he was seeing that fellow who translated Mishima… Wait, what was his name again…?

Angles: Do you mean [Meredith] Weatherby?

Takahashi: That's right. It was Weatherby who translated Confession of a Mask. We called him 'Tex Weatherby' back then because he was from Texas. Yatō was living with him and I won't beat around the bush—they were lovers. As Yatō's sexuality developed, he seems to have suffered some sort of emotional scar, and in his relationship with Weatherby, he seemed to experience both love and hate. [Silence]

He looked very masculine, but in fact, when it came to sexuality, he appears to have been quite feminine. He told me that himself once. Right before his death, he was engaging in dangerous sexual activities and ended up hurting himself quite a bit… [Silence] His liver and heart—his heart especially—became swollen and gorged. Even though he wasn't healthy, he continued to have extremely strenuous sex, and that's led some to speculate that it was that which lead to his death.

Angles: Really? I thought it was a heart attack or something.

Takahashi: You're right. I know the man whom Yatō was seeing just before he passed away. He never told me anything specific. But Yatō himself confessed to me all sorts of things before he died. He was describing exactly how he did it… [Laugh] He was doing it in quite strenuous ways. Later on, I realized what demands he must have placed on his heart.

Angles: And you were also good friends with the photographer Hosoe Eikoh, weren't you?

Takahashi: Oh yes, we still are. The other day, I gave a speech on Mishima, and Hosoe was sitting on the very first row. Afterward, he said, 'Mutsuo-san! That's was great, really great!' [Laugh] He has got such a kind personality. He's so easily moved. He hasn't changed a bit since the old days.

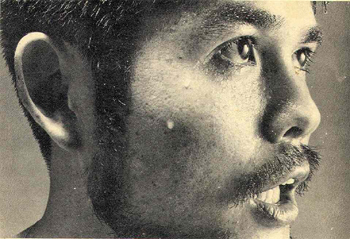

Angles: That photograph that he took of you was really something.

Figure 2: Photo of Takahashi Mutsuo by Hosoe Eikoh, 1970.

Source: Mutsuo Takahashi, Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato,

Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, back cover.

Photo reproduced with permission of the photographer.

Figure 2: Photo of Takahashi Mutsuo by Hosoe Eikoh, 1970.

Source: Mutsuo Takahashi, Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato,

Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, back cover.

Photo reproduced with permission of the photographer.

|

|

Takahashi: Oh yes. In that photo, he told me to sing.

Angles: You were singing?

Takahashi: And he was splashing water on top of me…

Angles: Really? I see. So you'd look like you were covered in sweat…

Takahashi: That's right. He took that photo of me like that while I was singing. But people seem to interpret that picture differently.

Angles: I thought maybe you were in the heat of passion or something… [Laugh]

|

Takahashi: Sure! Some people seem to think there's something right in front of me and I'm really turned on, but that's not how it really was.

Angles: I see.

Takahashi: Hosoe isn't that way at all ... I mean he's not the least bit gay. But he doesn't act the least bit funny when dealing with things having to go with gay sexuality. He is a really nice and straightforward fellow; nothing bad about his personality at all. So that day he was taking that picture, he just said, 'Mutsuo-san, I want to take a photo of you. You mind if I spray your face a bit to cover you with mist?' I told him to go ahead. Then after he wet my face, he said, 'Mutsuo-san, you always are singing, right? Sing me the song Egoika.' And that's how we got the photo.

Angles: I see.

Takahashi: A lot of cameramen took my picture over the years. In addition to Hosoe Eikoh, there was a fellow named Sawatari Hajime who also took photos of me. When I was much younger, he took nude shots of me. And who else? Oh yes, Richard Avedon. I remember him quite well.

Angles: Really, was that in Japan?

Takahashi: No. That was when I was abroad in New York.

Angles: What was the occasion?

Takahashi: I think that when we were doing advertisements for Suntory [back in the days I was working in advertising]. There were about five models, and I was helping to organize everything. So we talked, and I got to know him quite well. He was an interesting fellow who always paid lots of attention to small details.

Angles: I see. I didn't realize that you knew him. Let me change the subject once again. I want to talk a little bit about the poem Homeuta [Ode].[6] When we look back upon it from the vantage point of the present, we can see that it was quite revolutionary at the time it was published. I don't think that there was much mainstream poetry that described eroticism between men in such a bold and overwhelmingly detailed fashion. What was the reaction of the public at that time?

Takahashi: Well, that piece received good press. For instance, there was a periodical called Heibon panch [Ordinary Punch] that was probably the biggest selling magazine among young people during those days, and they called me in for an interview. Based on that, I suppose you could say it did attract quite a bit of attention. But when I wrote it, it wasn't my intention to write something sensational or anything. That work just came flowed from my pen completely naturally. That's usually the way it is with me. I just write in a quite natural way, and I'll probably continue to do so in the future.

Angles: Every time I reread that poem, I feel like you were writing in a way that would completely do away with the line separating so-called 'pure literature' and pornography.

Takahashi: That wasn't my original intention. I don't read that much 'pure literature,' nor do I read much pornography. Really, I just wrote on subjects that came naturally to me. I wasn't much of a reader back then. I read much more now than I did before.

Angles: I see. After the initial publication of Homeuta, you revised it, right?

Takahashi: A bit. But thinking about it now, I suspect that maybe the original was better.

Angles: Both the original and the revised version were translated into English so the anglophone world has access to both versions.[7] Now, soon after that, you published Zen no Henreki [Zen's Pilgrimage of Virtue].

Takahashi: Yes. I had always really wanted to write something like that. I was eager to write a kind of Bildungsroman that would describe one boy coming into his own as he explored the various gay spots of Tokyo. Luckily, the journal Umi [The Sea] decided to serialize Zen no Henreki. After several installments, it caught the attention of [the poet] Kusano Shinpei, who at that time was one of the most senior figures in the Japanese poetic world. When I went to his place one day, he told me, 'I read that work every month. What an astonishing, outrageous novel that is!' [Laugh]

Angles: [Laughing] Really?

Takahashi: He really looked after me. That novel sprung from my pen in a very natural way.

Angles: It seems to me that both Zen no Henreki and Homeuta have the theme of 'pilgrimages' in common. [Both describe a young man wandering through the homoerotic underground of a vast city with a devotion that borders on the religious.]

Takahashi: Sure enough. I suppose that has been a theme with me since my boyhood. I suppose you could call the pilgrimage a pattern for me. Even now, I think that pilgrimages form a fundamental literary theme in my writing.

Angles: Can you elaborate on that?

Takahashi: How shall I put it…? Rather than remaining at a certain place, I tend to wander around from one place to another, encountering various people and places. In the process, I either develop myself or, conversely, fall into depravity, if you know what I mean. [Laugh]

Angles: [Laughing] I see…

Takahashi: I think that theme forms an important thread running through who I am.

Angles: Your novel Seisho densetsu [A Legend of a Holy Place] also touches on the same theme, doesn't it?[8]

Takahashi: Well, you could say so, I guess. It represents one small episode, but yes.

Angles: The inspiration for the novel came from your trip to the United States in 1971, didn't it?

Takahashi: Yes, that's where I got some of the material for it. When I went there for Suntory, I had to write a sort of travelogue—nothing too long—about my reflections on the U.S. Well actually, it turned out more to be about New York City in particular.

I stayed in the city for about a month and half. My hotel was on Fifth Avenue in the Fifth Avenue Hotel. There was this fellow named Sakata Eiichirō who had learned from Richard Avedon. Maybe he was no longer associated with Richard's studio at that time, but I'm not quite sure… Anyway, I asked him to take photographs for me. Everyday, we went to a whole bunch of places in the Big Apple, and he took lots of photos that served as materials for the travelogue. In the evenings, [the film critic, Japanologist, and writer] Donald Richie and a few other people took me around to the gay spots and saunas throughout the city. [Laugh] Back then, no one had ever heard of AIDS so there was so much freedom and fun to be had.

Angles: Among your essays, there's one called 'Watashi no Nyū Yōku chizu' [My Map of New York].[9]

Takahashi: Oh yes, that's the travel sketch I wrote about the city.

Angles: In that essay, you wrote about how what a run down and decadent place New York was…

Takahashi: When I was young, I went to a Catholic church for a quite a long time, but I left before I ever got baptised. Even so, my experiences there still affected me tremendously. As a result, I had these images of places like Babylon and Rome in my head, and they overlapped with my impressions of New York to form a sort of geographical mosaic. In New York, I was amazed at how depraved humanity could become—a sort of modern Babylon. For me, however, that decadence was something truly enjoyable. Decadence is able to give people their freedom.

Angles: So what you are saying is that sort of decadence struck you as desirable?

Takahashi: How shall I put it…? There is a word in Japanese ranse that means 'a world in social disorder.' I think that when the world is in a state of depraved disorder—when the world is one of ranse—then artistic and literary expression take on their most vital forms. Much more vital and vibrant than during times of tranquility and peace… When I visited New York, I became keenly aware of that vitality.

Angles: I see.

Takahashi: In the case of Japan, we experienced a great deal of decadence in the years following the end of the Pacific War. Of course, that was not entirely the same. The zeitgeist was somewhat different…

Angles: Certainly, it was during that time that there was a flourishing of what was called 'literature of the flesh.'

Takahashi: That's right. No doubt about it.

Angles: It seems that certain literary themes arise at certain moments in history. During the 1970s when you were writing, the literary world seems to have been once again experiencing an era of 'literature of the flesh.'

Takahashi: In Japan, you mean?

Angles: Yes, in Japan. What do you think? It seems to me that during that time, Japan was once again experiencing a wave of writing about the body. What do you think?

Takahashi: I'm not exactly sure. Like I said, I don't write with those trends in mind. I am less concerned with the writing of other people so I'm not really sure how much that figured into their work.

Angles: I see. Those are just my own impressions of what was going on in Japanese literary history… Anyway, starting around 1975, it seems that the theme of homoeroticism became somewhat less prominent in your writings. It never disappeared completely, but it does seem to have become less of a salient theme.

Takahashi: That's true. I started writing on broader topics instead of continuing to take homoeroticism as my central theme. That doesn't mean that I lost my interest in homoeroticism at all, but I did lose my desire to write about exclusively. Instead, I became more interested in writing about different people and the world in which we live, but as I said, I am still interested in homoeroticism so perhaps later I will once again want to turn to writing about it again. I've only ever written about things that I want to write about it. Even now, I think that's the way to do it.

Angles: Male homoeroticism does resurface as a major theme in relatively recent pieces like 'Tankyūsha' (The Searcher) so it's clear you are still interested in the theme.[10]

Takahashi: Sure enough.

Angles: Before we conclude the interview today, I want to ask you about Shinjuku Ni-chōme these days. You have a special relationship with certain places like the bars Tak's Knot [Takkusu Notto] and Kronos [Kurosuno], right?

Takahashi: Yes, especially with Kronos. It's been almost two years since Kuro-chan, the young man who ran it, passed away.

Angles: What was his full name, if I may?

Takahashi: His name was Kurono Toshiaki. After his death, I felt as if an era had ended. Before he passed away, I went to the bars in Shinjuku Ni-chōme pretty often, but no longer.

Angles: For the sake of our readers, could you describe what kind of place Kronos was?

Takahashi: Well, Kronos was run by a gay man named Kurono Toshiaki who had a quite distinct personality. He loved the cinema in particular, but he also had broad interests in many of the arts. He read, researched, and enjoyed whatever interested him. As a result, a lot of people—not only gay men, but lots of other folks, businessmen and businesswomen, people involved in the arts and so on—went to his bar for the good conversation. He had quite a sharp tongue and said whatever he felt like, but because so many people felt affection for him, they crowded into his bar. When he passed away, I and a few other people published a memorial book of essays eulogizing him.[11] Quite a lot of people wrote essays for it. Among them were two people who had received the Order of Cultural Merit from the government. [Laugh] That's the kind of fellow Kurono Toshiaki was. [Moment of silence] When someone would say something trite and boring, he would spur them on by saying, 'Get outta here, and don't come back 'til you've done some more studying!' So there was a strange sort of classroom-like atmosphere inside the bar.

Angles: The bar still exists?

Takahashi: Well, the man who was managing the bar at the end just started his own small bar recently. What is it called? I can never remember, but anyway, he started his own bar there in Ni-chōme.

Ni-chōme sure has changed over time. But to me, Ni-chōme is still a kind of roji. You know, [the novelist] Nakagami Kenji often used this term [which means 'alley' but connotes a narrow street full of ramshackle places].

Angles: You mean he used it to refer to Ni-chōme?

Takahashi: No, no. To refer to his hometown. His family was from a buraku area and he referred to his hometown as a roji.[12] When he used the term roji, he was allegorically referring to some sort of untouchable space. A lot of ghettoised areas previously inhabited by people who suffered social discrimination have come to light and are now open to the eyes of the world, but that doesn't yet seem to have happened to Ni-chōme. In a sense, Ni-chōme is the last roji. I say this because I feel that even if other forms of social discriminations may disappear, discrimination having to do with gender and sexuality will be the last to vanish.

Angles: Why you say so?

Takahashi: I feel that is the most fundamental form of discrimination amongst human beings, and no matter what sorts of lovely, utopian claims people make, people will continue to differentiate between people based on sex and gender…

The last roji… I think that is what we find in Ni-chōme. It has changed quite a lot, and so it remains an open question how much of its roji-like character will remain. [Laugh] Towards the end of his life, Nakagami Kenji often went to Ni-chōme. I like to imagine that he thought of Ni-chōme as the last roji and that he was searching for those roji that he had once known but that had been lost to him.

Angles: As you mention, Ni-chōme has changed so much in the last twenty years or so. Where do you see those changes?

Takahashi: Well, I suppose that some of the dark parts of Ni-chōme have disappeared. Nowadays, I guess there is a sense of greater ease in that people are less embarrassed to use the word 'gay' to refer to themselves. At first glance, it looks as if there is greater recognition of people's rights, but because of that, we've lost many things in the process. All those shady parts and fine, sensitive delicacies that took place just out of view have gradually disappeared. I am not sure if this is entirely parallel, but a similar phenomenon can be found in the world of literature and the arts: there has been a gradual loss of delicacy. I think these two phenomena are somehow related. Unless one experiences some discrimination, some sort of secret, or something, one cannot produce fine literary expression. Or at least, that is what I believe.

Endnotes

[1] Takahashi published Jū-ni no enkei [Twelve Perspectives] in 1970. This lyrical collection of essays about the author's early life as an impoverished boy living in northern Kyushu deals with various aspects of his youth, but one of the foremost themes is his psychosexual development and early sexual experimentation with boys. For the advertising band (obi) that appeared around the book, Takahashi's close friend Mishima Yukio lauded this book of 'hard prose which shines with a black luster like that of a drawer expertly crafted by one of the master joiners of old.' Takahashi Mutsuo, Jū-ni no enkei, Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1970. For a translation of one essay from this volume, see Takahashi Mutsuo, 'The Snow of Memory,' trans. Jeffrey Angles, Japan: A Traveler's Literary Companion, ed. Jeffrey Angles and J. Thomas Rimer, Berkeley: Whereabouts Press, forthcoming 2006.

[2] In Japanese, 'chan' is a diminutive suffix added to someone's name to show affection.

[3] 'Osanai ōkoku kara' [From the Kingdom of Youth], written 1967-1968, is an earlier collection of Takahashi's remembrances of childhood. Like Jū-ni no enkei, this work describes the sexual relationship that developed between Takahashi and his adolescent uncle. Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Osanai ōkoku kara,' Takahashi Mutsuo shishū , Gendaishi bunko 19, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1969, pp. 89-103. Three of the essays, including one about his uncle, have been translated as Mutsuo Takahashi, 'Uncle; Orphan; Preparation for Poetry,' Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato,Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, pp. 43-45.

[4] In 1974, Takahashi published his longest piece of fiction to date, the surreal and often extremely humorous novel Zen no henreki [Zen's Pilgrimage of Virtue]. The book documents the experiences of a young man who, like Takahashi, comes to Tokyo and delves into its vast network of cruising spots, bathhouses, gay bars, and other homoerotic sites. Along the way, he is guided by the Buddhist bodhisattva Monjū, who according to popular premodern lore was the patron spirit of queer men. The novel concludes with the protagonist finally achieving unity with the universal spirit of the esoteric deity Dainichi Nyorai. (In Takahashi's story, Dainichi Nyorai is a gigantic golden phallus spewing out cock-shaped UFO messengers to the far reaches of the universe so that he might bring all creatures to enlightenment through sexuality.) Takahashi Mutsuo, Zen no henreki, Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1974. Parts of the novel are available in translation: Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Zen's Pilgrimage: Introduction,' trans. Jeffrey Angles, Harrington Gay Men's Fiction Quarterly vol. 2, no. 3 (2000):53-76; Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Zen's Pilgrimage: Conclusion,' trans. Jeffrey Angles, Queer Dharma: Voices of Gay Buddhists, vol. 2, ed. Winston Leyland, San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1999, pp. 198-222.

[5] This was Takahashi's second anthology

of poetry, but the first to earn him a national reputation. Many of the poems consist of paeans to men whom the narrators have loved. Takahashi Mutsuo, Bara no ki, nise no koibito-tachi, Tokyo: Gendaishi Kōbō, 1964, reprinted in Takahashi Mutsuo, Takahashi Mutsuo shishū, Gendaishi bunko 19, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1969, pp. 16-45. Some of the poems have been translated in Mutsuo Takahashi, Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Satō, Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975 and Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Poems by Takahashi Mutsuo,' trans. Jeffrey Angles, Intersections: Gender, History, and Context in the Asian Context vol. 12, January 2006.

[6] The long poem Homeuta [Ode] describes the experiences of a man wandering through the bathhouses and glory-hole filled restrooms of a city as he searches for one man who has ignited his fantasies. With its long strings of strikingly original metaphors describing the scent, touch, and taste of the man's penis, the poem caught the attention of many readers in Japan and was quickly translated into English, where it earned the admiration of Allen Ginsberg and other important American poets. Several years after its initial publication, Takahashi revised the poem for republication.

[7] Takahashi Mutsuo, Homeuta, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1971. Mutsuo Takahashi, 'Ode,' Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato, Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, pp. 47-107. For the revised version, see Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Homeuta,' Zoku Takahashi Mutsuo shishū , Gendaishi bunko 135, Tokyo: Shichōsha, 1995, pp. 22-53 and Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Ode,' trans. Hiroaki Sato, Partings at Dawn: An Anthology of Japanese Gay Literature, ed. Stephen D. Miller, San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1996, pp. 225-56.

[8] In 1971, Takahashi spent forty days in New York City. While there, he spent his time exploring the the vast network of gay bars, bathhouses, bookstores, and pornographic movie theatres that flourished before the scourge of AIDS. The novella Seisho densetsu [A Legend of a Holy Place], first published in Shinchō in 1972, combines Takahashi's own experiences with biblical themes to present a complicated, surreal, sometimes comic portrait of a hedonistic city where the protagonist explores his sexuality and the nature of homoerotic desire in general. Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Seisho densetsu,' Sei sankakkei, Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1972, pp. 165-238.

[9] After first appearing in the April 1971 issue of Otoko Joy, this essay was reprinted in Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Watashi no Nyū Yōku chizu,' Sei to iu ba, Tokyo: Ozawa Shoten, 1978, pp. 129-61.

[10] Takahashi Mutsuo, 'Tankyūsha,' Shinchō 91.11, Nov 1994, pp. 114-125. For a translation, see Takahashi Mutsuo, 'The Searcher,' trans. Stephen D. Miller, Partings at Dawn: An Anthology of Japanese Gay Literature, ed. Stephen D. Miller, San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1996, pp. 207-19.

[11] Takahashi Mutsuo (ed.), Arigatō sayonara, Fukiage, Saitama: Yūshin bunko, 2003.

[12] Buraku were areas where the lowest caste of Japanese society resided in the early modern period. (People from this class are generally called burakumin.) Although discrimination against this minority is less virulent than in the past, discrimination against people of buraku descent does continue to the present day, especially in rural areas.

|

Figure 1. Takahashi Mutsuo and Jeffrey Angles in Takahashi's garden on the day of the interview. Photo by Hanzawa Jun

Figure 1. Takahashi Mutsuo and Jeffrey Angles in Takahashi's garden on the day of the interview. Photo by Hanzawa Jun

Figure 2: Photo of Takahashi Mutsuo by Hosoe Eikoh, 1970.

Source: Mutsuo Takahashi, Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato,

Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, back cover.

Photo reproduced with permission of the photographer.

Figure 2: Photo of Takahashi Mutsuo by Hosoe Eikoh, 1970.

Source: Mutsuo Takahashi, Poems of a Penisist, trans. Hiroaki Sato,

Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1975, back cover.

Photo reproduced with permission of the photographer.