-

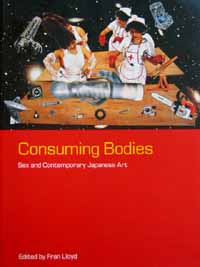

To my pleasant surprise, the cover of Consuming bodies shows a picture of my friend BuBu and Shimada Yoshiko dissecting a huge artificial penis. The work of these two women is prominently presented in various parts of the book, including their performance Made in Occupied Japan, sections of BuBu's Diary, in which she describes the experiences of a sex worker, and an afterword by Shimada Yoshiko, which problematises the eradication of history in Japan's current globalisation. While sex is present in their work, it is not the only theme and perhaps not even the major one. War is another major trope which can also be found throughout this book.

-

Clearly the editor Fran Lloyd is highly impressed by the two women who participated in the Japan 2001 Festival exhibition Sex and Consumerism: Contemporary Art in Japan, held in Brighton. Lloyd's book seems to be an effort to place their work in a broader perspective of contemporary Japanese art, at which she, I am afraid, did not entirely succeed. This is partly due to the focus on sex. In fact, the relation of over half of the chapters to the topic of sex and contemporary art is either very thin or wholly absent.

-

The first chapter, by Tim Screech, deals with the urban centers of the Edo period (1600-1868). The relation to contemporary art here must be sought in its possible historical sources. Screech briefly refers to the flourishing urban sexual culture about which he has written extensively elsewhere and suggests that the erotic woodblock prints called shunga, showing couples in sexual positions, have helped spread this urban culture throughout Japan.[1] The brunt of the chapter, however, deals with the make-up of the habitants of the major cities of the period. This is interesting in itself, but what purpose does it serve in the context of this book?

-

In the second chapter the journalist Nicholas Bornoff presents Japanese culture as governed by Confucianism. He regards the supposed abundance of sex in Japanese art as a reaction to the rigidity of Confucianism. However, among specialists of Japan, Confucianism is not seen as playing much of a role in contemporary Japan, making Bornoff's argument lack a relation to scholarship of the field. The shock value he attributes to sex in Japanese art is probably felt more strongly in England than in Japan.

-

Fran Lloyd, who wrote the third chapter, is a scholar of art but not specialised in Japan, which may be seen reflected in her selection of art works for discussion, which Takatani Shiro of the Kyoto-based multi-media performance group dumb type sees as characteristic of what western people like to see in Japan, rather than as representative of Japanese art. BuBu met Lloyd in Brighton but said they hardly spoke. BuBu remarked that she is highly disgusted by some of the works (whose creators use sex workers merely as objects) in the context of which hers are placed in Lloyd's text as they were in Brighton. Lloyd's lack of knowledge of Japan brings her to present host clubs as places where sex is for sale (pp. 74-75), which is not the case. Her writing about audiences being horrified at seeing BuBu pull a dozen flags from her vagina at the performance S/N by dumb type (p. 90), reflects a typical English reaction to sexual matters. Audiences with whom I have viewed S/N in continental Europe and Japan have never shown themselves to be horrified and BuBu's intention was for her act, rather than horrifying an audience, to be soothing after the harsh light, text and music section preceding it. Both Lloyd and Bornoff's writing suggests an over-eagerness to sexualise and sensationalise phenomena that are seen as exotic, which is all too common in an Orientalist strain of writing on Japan.

-

They are followed by two Japanese authors. Hasegawa Yuko, the curator of a modern art museum (i.e. exposition space) in Kanagawa, presents a chapter on gender and art, reiterating the kawaii [cute] boom of the 1980s, when she maintains everything in Japan was colored 'pink'. She argues that Japanese art has since developed towards a more mature investigation of a de-gendered 'white'. Her reasoning is spectacular in places but, as is not uncommon in such cases, its basis seems a bit shaky. It remains unclear what relation her essay has with the topic of sex in Japanese art, unless we accept that gender is somehow naturally included in the topic of sex, a proposition that is not made in this book.

-

Matsui Midori, a professor of American Studies at Tôhoku University in Sendai, follows with a fascinating investigation of the relationship between the angura [underground] culture of the 1960s and contemporary Japanese art. While important in itself and a must-read for those interested in Japanese art from the 1960s onwards, there is even less of a relation to Lloyd's topic of sex in Japanese art than in the former chapter. Instead, Matsui involves herself with questions concerning nationalism and racism and the work of people like Aida Makoto on war—for instance his 1970s, but since 9/11 extremely topical painting of Japanese planes bombing New York, also discussed by Bornoff—and relations between Japan and its neighbors, not unlike BuBu and Shimada.

-

The final chapter by Stephen Barber is a beautifully written account of several works of the Japanese performance group Kaitaisha, which has its roots in 1970s angura culture. He finds that Tokyo performers of the 1960s drew their themes from both the sexual culture present in the Kabukichô area in Shinjuku, which today is still known for its enormously varied offer of sexual services, and the violent political protests and riots that marked the era, leading to a 'volatile mix' (p. 184). However, as in the case of the preceding Japanese authors, the link to sex in art remains thin, if not absent. Though in itself an interesting account, in relation to the book topic it seems rather like a filler, not unlike the two previous chapters.

-

The book offers some insights into sex and art in Japan and some into questions of nationality and racism in relation to art and Japanese art history in general. The quality of the chapters varies greatly. It may be seen more as a coffee-table book than a serious attempt at investigating Japanese art, although the size of the pictures suggests that it was meant to be taken more seriously. The abundance of pictures may make it useful for teaching, but I hope teachers would replace some of the texts complementing the images with more thorough reading material. Regrettably, Lloyd and Bornoff's chapters give vent to the prejudice—present among for instance Japanese academics specialising in art—that Japanese art can never be properly understood by Europeans as well as to the widespread prejudice that Brits cannot deal adequately with sex. The focus on sex seems to have be one with which the Japanese authors were not comfortable, while the British authors seem to have felt unable to deal with homosexuality, which is conspicuously absent. It might have worked better if the book had been cast and edited as focusing on gender and nationalism, with sex as a side-dish. In this manner, the work of BuBu and Shimada could have been placed more clearly in relation to the writings of Hasegawa, Matsui and Barber, which are the best chapters.

Endnote

�

[1] Timon Screech, Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan 1700-1820, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 28.

|